Information Alienation and Circle Fracture: Policy Communication and Opinion-Generating Networks on Social Media in China from the Perspective of COVID-19 Policy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Public Sphere and Political Communication

2.2. Social Network and Semantic Network Analysis for Policy Communication

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Research Method

3.2. Research Design and Variable Definitions

3.2.1. Core Communicators and Definitions

- China central mainstream media;

- Local mainstream media;

- Governmental new media;

- Online media;

- Experts;

- Online key opinion leaders.

3.2.2. Semantic Network

3.2.3. Sentiment Extremum

4. Finding and Discussion

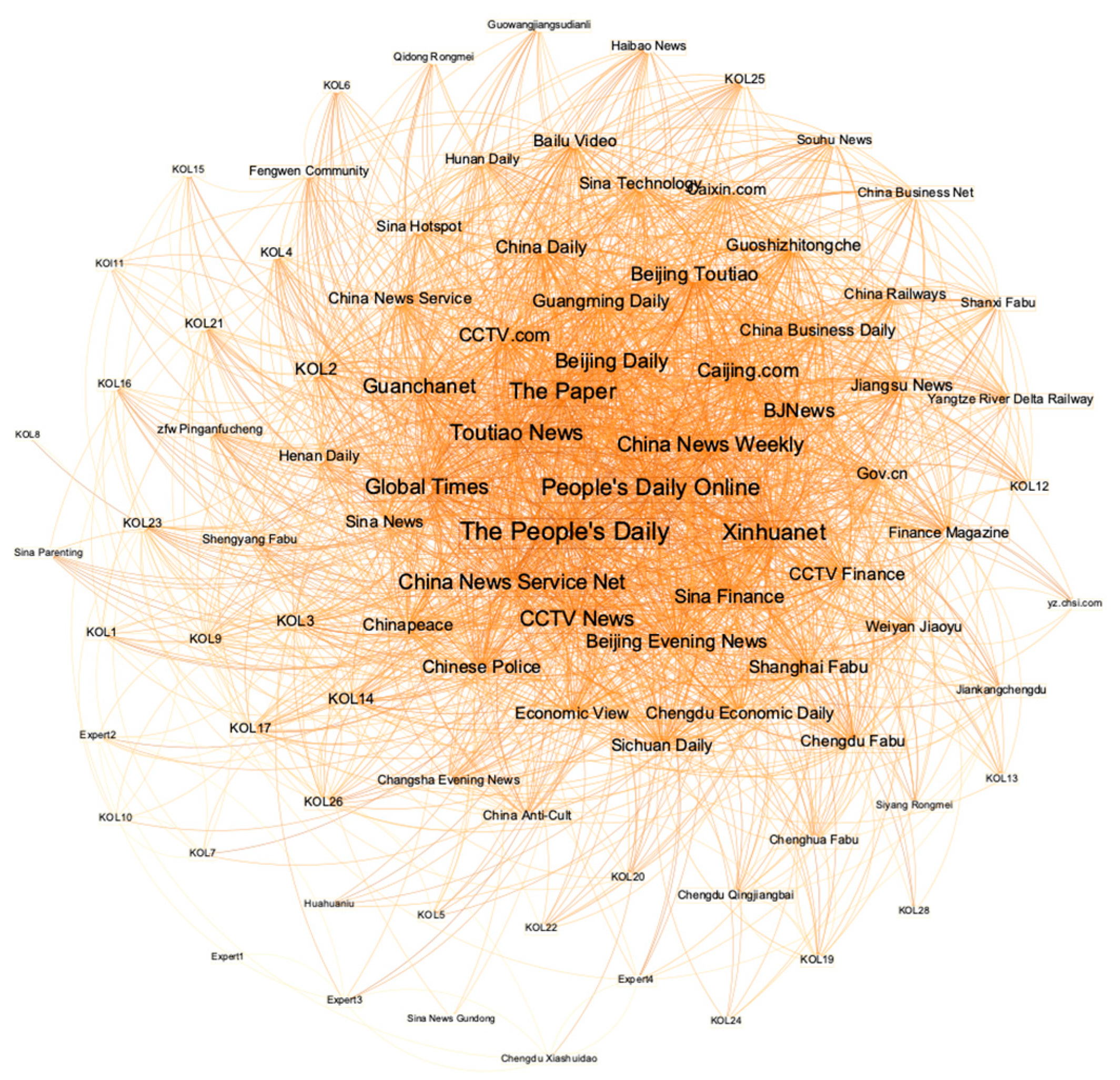

4.1. Overall Structure of the “New Ten Articles” Communication Network on Sina Weibo

4.1.1. Structure: Flattening and Partial Interaction of Opinion Leaders

4.1.2. Low Network Density and Thick Barriers in the Information Circulation Circle

4.2. Semantic Network: Information Asymmetry between Core Communication Content and Public Demand

4.3. Sentiment Significant Concepts and Diffusion Association

4.3.1. Positive and Negative Semantic Emotion Networks

4.3.2. Semantic Emotion Diffusion and Public Emotion Reflection

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Couldry, N. Media, Society, World: Social Theory and Digital Media Practice; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hayles, N.K. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mihelj, S.; Jiménez-Martínez, C. Digital nationalism: Understanding the role of digital media in the rise of ‘new’nationalism. Nations Natl. 2012, 27, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. Int. J. Commun. 2007, 1, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Karpf, D. Blogosphere research: A mixed-methods approach to rapidly changing systems. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2009, 24, 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, X. Exploring the New Atmosphere for Chinese Political Communication. J. Renmin Univ. China 2016, 30, 74–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The State Council of The People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-12/07/content5730475.htm (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Zhao, J.; Jing, X. The relationship Between Political Communication and Health Communication in Public Health Emergencies. J. Commun. Rev. 2021, 74, 34–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zizek, S. How to Read Lacan; Granta Books: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Engesser, S.; Ernst, N.; Esser, F.; Büchel, F. Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieglitz, S.; Dang-Xuan, L. Emotions and information diffusion in social media—Sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 29, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; lan, J. Emotion in the Age of Digital Capitalism—From Life to Production to Governance. Foreign Theor. Trends 2013, 533, 114–124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Papacharissi, Z. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S.K.; Pearce, K.E.; Vitak, J.; Treem, J.W. Explicating affordances: A conceptual framework for understanding affordances in communication research. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2017, 22, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, G.J.; Ewing-Nelson, S.R.; Mackey, L.; Schlitt, J.T.; Marathe, A.; Abbas, K.M.; Swarup, S. Semantic network analysis of vaccine sentiment in online social media. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3621–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieglitz, S.; Dang-Xuan, L. Political communication and influence through microblogging—An empirical analysis of sentiment in Twitter messages and retweet behavior. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 3500–3509. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, M.; Fischer, T.; Riedl, R. Impact of content characteristics and emotion on behavioral engagement in social media: Literature review and research agenda. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 21, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papacharissi, Z. Affective publics and structures of storytelling: Sentiment, events and mediality. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil de Zúñiga, H.; Molyneux, L.; Zheng, P. Social media, political expression, and political participation: Panel analysis of lagged and concurrent relationships. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 612–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M.; Usher, N. Framing in a fractured democracy: Impacts of digital technology on ideology, power and cascading network activation. J. Commun. 2018, 68, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W.L.; Segerberg, A. The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vromen, A.; Xenos, M.A.; Loader, B. Young people, social media and connective action: From organisational maintenance to everyday political talk. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 18, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaast, E.; Safadi, H.; Lapointe, L.; Negoita, B. Social Media Affordances for Connective Action. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 1179–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LanEscobar, O.; Elstub, S. Forms of mini-publics: An introduction to deliberative innovations in democratic practice. J. Res. Dev. Not 2017, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Thimm, C. The mediatization of politics and the digital public sphere: The dynamics of mini-publics. In Citizen Participation and Political Communication in a Digital World; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, X. An Outline of Micro Political Communication. Mod. Commun. 2021, 43, 16–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, G.; Schulz, W. Mediatization of politics: A challenge for democracy? Political Commun. 1999, 16, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömbäck, J. Four phases of mediatization: An analysis of the mediatization of politics. Int. J. Press/Politics 2008, 13, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castells, M. The new public sphere: Global civil society, communication networks, and global governance. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2008, 616, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stieglitz, S.; Dang-Xuan, L. Social media and political communication: A social media analytics framework. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2013, 3, 1277–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.M.; Falvey, L. Democracy and new communication technologies. Media Commun. 2001, 1, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijck, J.; Poell, T. Understanding social media logic. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2013, 25, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jing, X.; Chen, S. Returning to the Powerful Effect: Reflections on the Effects of Western Political Communication in the 21st Century. Soc. Sci. Abroad 2022, 4, 21–34, 196. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mazali, T. Social media as a new public sphere. Leonardo 2011, 44, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide. Can. J. Commun. 2003, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, D. Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability; Open University: Hong Kong, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Knoke, D. Policy networks. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2011; pp. 210–222. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S. Analysis of Three Research Perspectives of Western Policy Network Theory. CASS J. Political Sci. 2013, 4, 87–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhao, G.; Guo, X. Research on the Network Public Opinion Propagation Model of Major Epidemics Under the Cross-infection of Double Emotions. J. Syst. Simul. 2023, 3, 1–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Jing, X. On Emotions in the Micro Political Communication of the Individual as the Subject. Soc. Sci. Nanjing 2022, 7, 111–120. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G. Economic Sociology; Fudan University Press: Shanghai, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Casero-Ripollés, A.; Alonso-Muñoz, L.; Marcos-García, S. The influence of political actors in the digital public debate on twitter about the negotiations for the formation of the government in Spain. Am. Behav. Sci. 2022, 66, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, A. Influencers in the political conversation on twitter: Identifying digital authority with big data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, G.; Cauteruccio, F.; Corradini, E.; Marchetti, M.; Pierini, A.; Terracina, G.; Virgili, L. An approach to detect backbones of information diffusers among different communities of a social platform. Data Knowl. Eng. 2022, 140, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Shirey, P.R. LS sets, lambda sets and other cohesive subsets. Soc. Netw. 1990, 12, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Park, C.; Wilding, M. Identifying policy frames through semantic network analysis: An examination of nuclear energy policy across six countries. Policy Sci. 2015, 48, 51–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, S.L.; King, E.J.; da Fonseca, E.M.; Peralta-Santos, A. The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1413–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervi, L.; García, F.; Marín-Lladó, C. Populism, Twitter, and COVID-19: Narrative, fantasies, and desires. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enli, G. Twitter as arena for the authentic outsider: Exploring the social media campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election. Eur. J. Commun. 2017, 32, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonifazi, G.; Corradini, E.; Ursino, D.; Virgili, L. New Approaches to Extract Information from Posts on COVID-19 Published on Reddit. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2022, 21, 1385–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R.S. The social capital of opinion leaders. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1999, 566, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, M.; Pollet, T.V.; Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. Perceived group cohesion versus actual social structure: A study using social network analysis of egocentric Facebook networks. Soc. Sci. Res. 2008, 68, 243–253. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale, F. Two narratives of platform capitalism. Yale Law Policy Rev. 2016, 35, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, P.; Leyshon, A. Platform capitalism: The intermediation and capitalization of digital economic circulation. Financ. Soc. 2017, 3, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barassi, V.; Treré, E. Does Web 3.0 come after Web 2.0? Deconstructing theoretical assumptions through practice. New Media Soc. 2012, 14, 1269–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennett, W.L.; Pfetsch, B. Rethinking political communication in a time of disrupted public spheres. J. Commun. 2018, 68, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, D. Spiral of silence in the social media era: A simulation approach to the interplay between social networks and mass media. Commun. Res. 2022, 49, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.A.; Guess, A.; Barberá, P.; Vaccari, C.; Siegel, A.; Sanovich, S.; Nyhan, B. Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. Political Polariz. Political Disinf. A Rev. Sci. Lit. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Wray, R.J. Tailored and targeted health communication: Strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am. J. Health Behav. 2023, 27, S227–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Kong, H. Online health information seeking: A review and meta-analysis. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Dutta, M.J. The relationship between health information seeking and community participation: The roles of health information orientation and efficacy. Health Commun. 2008, 23, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boettke, P.; Powell, B. The political economy of the COVID-19 pandemic. South. Econ. J. 2021, 87, 1090–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C. Ambiguities and contradiction: Issues in China’s changing political communication. Gazette 1994, 53, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Luo, L.; Wu, S. Influence and extension of the spiral of silence in social networks: A data-driven approach. In Social Network Based Big Data Analysis and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

| Centrality | Re-Post Volume | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Account (@) | Degree Centrality | Account (@) | Volume |

| People’s Daily | 86.96 | KOL1 | 6414 |

| CCTV news | 82.61 | China News Weekly | 4308 |

| People’s Daily Online | 76.09 | People’s Daily | 3804 |

| Toutiao News | 75.00 | KOL2 | 3023 |

| The Paper | 72.83 | The Paper | 2695 |

| Global Times | 70.65 | Guanchanet | 2587 |

| China News Service | 68.48 | CCTV news | 2223 |

| Xinhuanet | 68.48 | Bailu Video | 1543 |

| Guanchanet | 61.96 | Expert1 | 1471 |

| China News Weekly | 61.96 | Guowangjiangsu Dianli | 1394 |

| Beijing Daily | 60.87 | KOL3 | 1025 |

| Sina Finance | 57.61 | KOL4 | 984 |

| Beijing News | 57.61 | KOL5 | 981 |

| CCTV.com | 56.52 | CCTV news | 910 |

| Caijing.com | 56.52 | Souhu News | 904 |

| Beijing Toutiao | 55.44 | KOL6 | 760 |

| Guangming Daily | 51.09 | China Daily | 748 |

| CCTV Finance | 51.09 | Expert2 | 738 |

| Beijing evening news | 50.00 | KOL7 | 733 |

| China Daily | 50.00 | Expert3 | 731 |

| Interaction Type | Interaction Level | Accounts |

|---|---|---|

| Weak Interaction (0–12) | Level1 (0–6) Level2 (7–12) | 38 16 |

| Medium Interaction (12–24) | Level3 (13–18) Level4 (19–24) | 20 15 |

| Strong Interaction (25–36) | Level5 (25–30) Level6 (31–36) | 2 9 |

| Type | Pearson Correlation | p |

|---|---|---|

| Online Opinion Leaders (Positive content) | −0.108 | 0.767 |

| Online Opinion Leaders (Negative content) | 0.722 1 | 0.043 |

| Experts | 0.712 1 | 0.031 |

| Central Mainstream Media | 0.088 | 0.786 |

| Online Media | 0.819 2 | 0.003 |

| Local Mainstream Media | 0.539 1 | 0.047 |

| Governmental New Media | 0.081 | 0.849 |

| Type | Sentiment Score (Posts) 1 | Sentiment Extremum (Re-Posts) 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Online Opinion Leaders (Positive content) | −4 | 0.33 |

| −8 | −0.93 | |

| −2 | −0.11 | |

| −6 | −0.87 | |

| −8 | −0.64 | |

| Experts | −8 | −0.64 |

| 6 | 0.74 | |

| 0 | 0.19 | |

| 2 | 0.9 | |

| 10 | 1 | |

| Online Media | 3 | 0.02 |

| 6.3 | −0.13 | |

| 3 | −0.54 | |

| 0 | −0.12 | |

| −11.8 | −0.92 | |

| Local Mainstream Media | 13 | 0.73 |

| 5 | 0.44 | |

| 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, Y.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Y. Information Alienation and Circle Fracture: Policy Communication and Opinion-Generating Networks on Social Media in China from the Perspective of COVID-19 Policy. Systems 2023, 11, 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11070340

Dai Y, Cheng X, Liu Y. Information Alienation and Circle Fracture: Policy Communication and Opinion-Generating Networks on Social Media in China from the Perspective of COVID-19 Policy. Systems. 2023; 11(7):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11070340

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Yuanchu, Xinyu Cheng, and Yichuan Liu. 2023. "Information Alienation and Circle Fracture: Policy Communication and Opinion-Generating Networks on Social Media in China from the Perspective of COVID-19 Policy" Systems 11, no. 7: 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11070340

APA StyleDai, Y., Cheng, X., & Liu, Y. (2023). Information Alienation and Circle Fracture: Policy Communication and Opinion-Generating Networks on Social Media in China from the Perspective of COVID-19 Policy. Systems, 11(7), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11070340