How Does Rural Resilience Affect Return Migration: Evidence from Frontier Regions in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

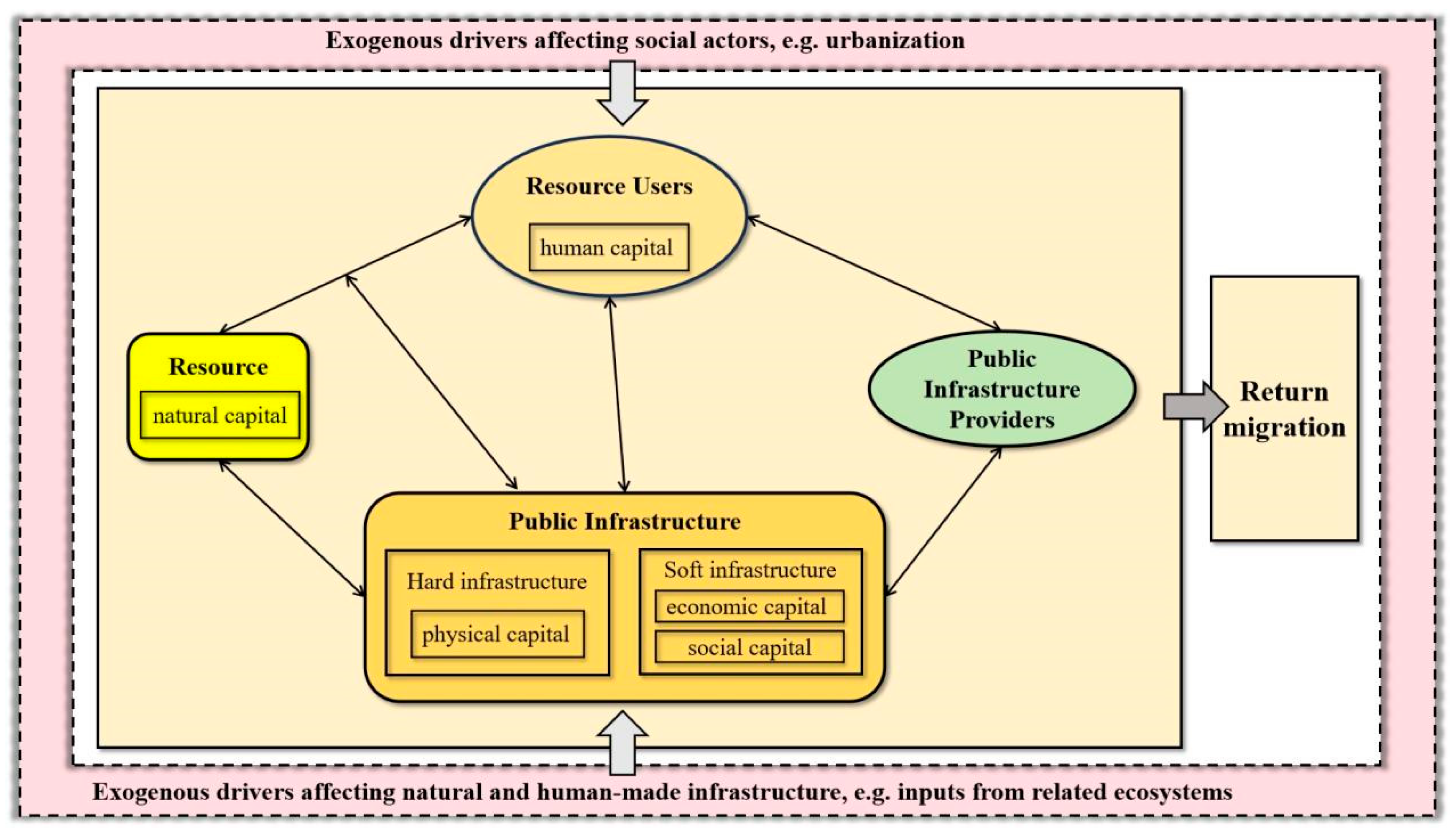

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Framework

3. Data Sources and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Selection and Index System

3.3. Methods and Models

3.3.1. Index System Construction

3.3.2. Variable Calibration

3.3.3. Application of NCA and fsQCA

3.3.4. Analysis of Necessary Conditions

4. Results

4.1. Configuration Analysis

4.1.1. The Social–Ecological System Configurations Resulting in High Rural Return Migration Rate

4.1.2. The Social–Ecological System Configurations Resulting in Non-High Rural Return Migration Rate

5. Discussion

5.1. Longitudinal Comparison of High Return Migration Rate Configurations

5.1.1. High Return Migration Rate Configurations Dominated by Public Infrastructure Providers

5.1.2. High Return Migration Rate Configurations Dominated by Human Capital and Social Capital

5.1.3. Substitution Between Public Infrastructure Providers and Livelihood Capitals

5.2. Lateral Comparison of High Return Migration Rate Configurations

5.2.1. Natural Capital Is Not a Key Condition for Realizing a High Level of Return Migration

5.2.2. Economic Capital Is Likewise Not a Key Condition for Achieving a High Level of Return Migration

5.2.3. Human Capital as a Key Condition for Achieving a High Level of Return Migration

5.3. Low-Level Return Migration Configurations Analysis

5.3.1. The Decline of Social Capital

5.3.2. Loss of Public Infrastructure Providers

5.3.3. Inputs of Economic Capital Cannot Reverse the Trend of Return Migration Towards Vulnerability

5.3.4. A Single Input of Physical Capital Does Not Create a Stable Trend of Return Migration

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Construction of Variables and Index System

| CIS Framework | Livelihood Capitals | Specific Indicators |

| Resource | Natural capital | Landform |

| Characteristic natural resources | ||

| Water availability | ||

| Cultivated area | ||

| Fragmentation of cultivated land | ||

| Forest area | ||

| Soil fertility | ||

| Resource Users | Human capital | Proportion of population under 12 and over 60 |

| Labor proportion | ||

| Labor structure | ||

| Role of village committee | ||

| Number of skills training sessions conducted | ||

| Have a secondary vocational school | ||

| Public Infrastructure | Physical capital | Whether there is an e-commerce point of sale or service |

| Number of households with broadband network installed | ||

| Cultivated land transfer quantity | ||

| Diversity of public space | ||

| Number of supermarkets or small shops | ||

| Frequency of use of agricultural machinery | ||

| Number of clinics | ||

| Whether it is equipped with suitable aging facilities | ||

| Economic capital | Hierarchy of economic power | |

| Per capita net income | ||

| Collective economic income | ||

| Contact frequency with enterprises or market entities outside the village | ||

| Characteristic industry type | ||

| Average price of land transfer | ||

| Whether it is located on the outskirts of the city | ||

| Social capital | Neighborhood relationship | |

| Relationship between cadres and masses | ||

| Frequency of contact with other villages | ||

| Number of inspections by superior leaders | ||

| Frequency of cultural and sports activities | ||

| Public infrastructure providers | — | Number of village committee members |

| First secretary job recognition | ||

| Role of villagers’ council | ||

| Number of economically active cooperatives | ||

| Frequency of obtaining higher government policy or financial support in the past three years | ||

| Whether there are university graduates among the officers and cadres of public organizations | ||

| Party membership |

Appendix A.2. Results of the Analysis of the Necessary Conditions for the NCA Method

| Antecedent Condition a | Method | Precision | Ceiling Zone | Scope | Effect Size (d) b | p-Value |

| Natural capital | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Economic capital | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Physical capital | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Human capital | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Social capital | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 0.032 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 0.032 | |

| Public infrastructure providers | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Note: a. Calibrated fuzzy set affiliation value. b. 0.0 ≤ d < 0.1: “small effect”; 0.1 ≤ d < 0.3: “medium effect”; 0.3 ≤ d < 0.5: “large effect”; 0.5 ≤ d: “very large effect”. | ||||||

Appendix A.3. NCA Method Bottleneck Level (%) Analysis Results a

| Returning Activity | Natural Capital | Economic Capital | Physical Capital | Human Capital | Social Capital | Public Infrastructure Providers |

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 50 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 60 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 70 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 80 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 90 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 100 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 1.0 | NN |

| Note: NN = not necessary. | ||||||

Appendix A.4. Necessity Test for Individual Conditions of the QCA Method

| Antecedent Variables | Outcome Variables | |

| High Return Migration Rate | Non-High Return Migration Rate | |

| Natural capital | 0.512 | 0.568 |

| ~Natural capital | 0.587 | 0.526 |

| Economic capital | 0.517 | 0.573 |

| ~Economic capital | 0.577 | 0.517 |

| Physical capital | 0.545 | 0.531 |

| ~Physical capital | 0.529 | 0.539 |

| Human capital | 0.553 | 0.537 |

| ~Human capital | 0.553 | 0.564 |

| Social capital | 0.574 | 0.492 |

| ~Social capital | 0.505 | 0.583 |

| Public infrastructure providers | 0.589 | 0.503 |

| ~Public infrastructure providers | 0.508 | 0.590 |

| Note: “~” means logic negation (i.e., non-high). | ||

Appendix A.5. Robustness Tests for Increasing Frequency Thresholds

| Antecedent Condition | High Return Migration Rate (The Frequency Threshold Is 1) | High Return Migration Rate (The Frequency Threshold Is 2) | ||||

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H1′ | H3′ | |

| Natural capital |  |  |  | ⬤ |  |  |

| Economic capital |  |  |  | ⬤ |  |  |

| Physical capital |  |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |

| Human capital |  | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ |  | ● |

| Social capital |  | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |  |  |

| Public infrastructure providers | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| Consistency | 0.851 | 0.840 | 0.864 | 0.858 | 0.851 | 0.864 |

| Raw coverage | 0.067 | 0.070 | 0.073 | 0.055 | 0.067 | 0.073 |

| Unique coverage | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.030 | 0.042 | 0.049 |

| Solution consistency | 0.836 | 0.849 | ||||

| Solution coverage | 0.189 | 0.116 | ||||

Note: ⬤ = core condition exists;  = core condition does not exist; ● = marginal condition exists; = core condition does not exist; ● = marginal condition exists;  = marginal condition does not exist. = marginal condition does not exist. | ||||||

Appendix A.6. Robustness Tests for Increasing RAW Consistency Thresholds

| Antecedent Condition | High Return Migration Rate (The RAW Consistency is 0.80) | High Return Migration Rate (The RAW Consistency is Increased to 0.85) | |||||

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H1′ | H3′ | H4′ | |

| Natural capital |  |  |  | ⬤ |  |  | ⬤ |

| Economic capital |  |  |  | ⬤ |  |  | ⬤ |

| Physical capital |  |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |  | ⬤ | ● |

| Human capital |  | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| Social capital |  | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |  |  | ⬤ |

| Public infrastructure providers | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |  |

| consistency | 0.851 | 0.840 | 0.864 | 0.858 | 0.851 | 0.864 | 0.858 |

| raw coverage | 0.067 | 0.070 | 0.073 | 0.055 | 0.067 | 0.073 | 0.055 |

| unique coverage | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.030 | 0.042 | 0.040 | 0.035 |

| solution consistency | 0.836 | 0.851 | |||||

| solution coverage | 0.189 | 0.150 | |||||

Note: ⬤ = core condition exists;  = core condition does not exist; ● = marginal condition exists; = core condition does not exist; ● = marginal condition exists;  = marginal condition does not exist. = marginal condition does not exist. | |||||||

Appendix A.7. Robustness Tests for Increasing PRI Consistency Thresholds

| Antecedent Condition | High Return Migration Rate (The PRI Consistency Is 0.70) | High Return Migration Rate (The PRI Consistency Is Increased to 0.74) | |||||

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H1′ | H3′ | H4′ | |

| Natural capital |  |  |  | ⬤ |  |  | ⬤ |

| Economic capital |  |  |  | ⬤ |  |  | ⬤ |

| Physical capital |  |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |  | ⬤ | ● |

| Human capital |  | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| Social capital |  | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |  |  | ⬤ |

| Public infrastructure providers | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |  |

| Consistency | 0.851 | 0.840 | 0.864 | 0.858 | 0.851 | 0.864 | 0.858 |

| Raw coverage | 0.067 | 0.070 | 0.073 | 0.055 | 0.067 | 0.073 | 0.055 |

| Unique coverage | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.030 | 0.042 | 0.040 | 0.035 |

| Solution consistency | 0.836 | 0.851 | |||||

| Solution coverage | 0.189 | 0.150 | |||||

Note: ⬤ = core condition exists;  = core condition does not exist; ● = marginal condition exists; = core condition does not exist; ● = marginal condition exists;  = marginal condition does not exist. = marginal condition does not exist. | |||||||

References

- Ali, S.; Ahmad, N. Human capital and poverty in Pakistan: Evidence from the Punjab province. Eur. J. Sci. Public Policy 2013, 11, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Anderies, J.M.; Janssen, M.A.; Ostrom, E. A framework to analyze the robustness of social-ecological systems from an institutional perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderies, J.M.; Janssen, M.A.; Schlager, E. Institutions and the performance of coupled infrastructure systems. Int. J. Commons 2016, 10, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderies, J.M.; Janssen, M.A. Robustness of social—Ecological systems: Implications for public policy. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 513–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.; He, Y. Return or Migrate? Labor Return in Anhui and Sichuan Provinces. Sociol. Stud. 2002, 3, 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bogue, D.J. Components of population change: 1940–1950: Estimates of net migration and natural increase for each standard metropolitan area and state economic area. Population 1958, 13, 328. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, M.H. Does migration raise agricultural investment? An empirical analysis for rural Mexico. Agric. Econ. 2015, 46, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, G.; Glasgow, N. Entrepreneurial behaviour among rural in-migrants. In Rural Transformations and Rural Policies in the US and UK; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; pp. 138–155. [Google Scholar]

- Brugere, C.; Lingard, J. Irrigation deficits and farmers’ vulnerability in Southern India. Agric. Syst. 2003, 77, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Luo, J.C. Social capital, financial literacy and farmers’ entrepreneurial financing behavior. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2019, 3, 3–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cassarino, J.P. Theorising return migration: The conceptual approach to return migrants revisited. Int. J. Multicult. Soc. 2004, 6, 253–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccone, A.; Papaioannou, E. Human capital, the structure of production, and growth. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2009, 91, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L. Livelihood sustainability of rural households in response to external shocks, internal stressors and geographical disadvantages: Empirical evidence from rural China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.M.; Yan, F.X. Does livelihood capital suppress relative poverty among rural residents? A dual perspective based on level and structure. J. China Agric. Univ. 2023, 28, 244–262. [Google Scholar]

- Dul, J.; Hauff, S.; Bouncken, R.B. Necessary condition analysis (NCA): Review of research topics and guidelines for good practice. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2023, 17, 683–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; Van der Laan, E.; Kuik, R. A statistical significance test for necessary condition analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 23, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J. Identifying single necessary conditions with NCA and fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.P.; Fan, J.; Shen, M.Y.; Song, M.Q. Sensitivity of livelihood strategy to livelihood capital in mountain areas: Empirical analysis based on different settlements in the upper reaches of the Minjiang River, China. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 38, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.S.; Yin, G.Q. Research on the Mechanism of the Role of Capital Flowing to the Countryside in the Return of Rural Migrant Labor. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. pp. 1–14. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.3513.S.20240829.1340.008.html (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Leonardo, M.; López-Gay, A.; Newsham, N.; Recaño, J.; Rowe, F. Understanding patterns of internal migration during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Popul. Space Place 2022, 28, e2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greckhamer, T.; Furnari, S.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Studying configurations with qualitative comparative analysis: Best practices in strategy and organization research. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.Y.; Qin, X.L.; Shen, T.Y. Spatial variation of migrant population’s return intention and its determinants in China’s prefecture and provincial level cities. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 1877–1890. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, G. Autonomous Region Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in 2017. Available online: http://tjj.gxzf.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/ndgmjjhshfz/t2382810.shtml (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Department of Human Resources and Social Security. Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Human Resources and Social Security in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region for the Year 2022. Available online: http://rst.gxzf.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/tjxx/tjgb/t16815411.shtml (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Hausmann, R.; Nedelkoska, L. Welcome home in a crisis: Effects of return migration on the non-migrants’ wages and employment. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2018, 101, 101–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, K.; Lilleør, H.B. Going back home: Internal return migration in rural Tanzania. World Dev. 2015, 70, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.S.; Wang, Y.H.; Zhang, P.L. Anti-urbanization and rural development: Evidence from return migrants in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 103, 103102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, J.X.; Huang, J.K. Policy support, social capital, and farmers’ adaptation to drought in China. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 24, 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Xu, H.Z.; Guo, Y.Y. Research on the impact of rural land confirmation on the return of rural labor force—An empirical analysis based on CLDS data. Land Econ. Res. 2022, 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Junge, V.; Diez, J.R.; Schätzl, L. Determinants and consequences of internal return migration in Thailand and Vietnam. World Dev. 2015, 71, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshmaram, M.; Shiri, N.; Shinnar, R.S.; Savari, M. Environmental support and entrepreneurial behavior among Iranian farmers: The mediating roles of social and human capital. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 1064–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.N.; Mahmud, M.; Morduch, J.; Ravindran, S.; Shonchoy, A.S. Migration, externalities, and the diffusion of COVID-19 in South Asia. J. Public Econ. 2021, 193, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S. A theory of migration. Demography 1966, 3, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.J. Urban-to-Rural Return Migration in Korea; Seoul National University Press: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.L.; Yang, S.Q.; Liao, H.P. Research on the spatial pattern and coupling relationship between rural economic resilience and cultivated land fragmentation: A case study of Fengjie County, Chongqing. J. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Xie, Z. Spatial distribution of floating young talents and influencing factors of their settlement intention-Based on the dynamic monitoring data of the national floating population in 2017. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Liang, Z. Heterogeneous effects of return migration on children’s mental health and cognitive outcomes. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 122, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y. Bottom-up initiatives and revival in the face of rural decline: Case studies from China and Sweden. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R.; Fan, P.C.; Liu, Y.S. What makes better village development in traditional agricultural areas of China? Evidence from long-term observation of typical villages. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.M.; Yang, Y.Y.; Du, G.M.; Huang, S.L. Understanding the contradiction between rural poverty and rich cultivated land resources: A case study of Heilongjiang Province in Northeast China. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.B.; Loyalka, P.; Rozelle, S.; Wu, B.Z. Human capital and China’s future growth. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Yan, J.Y.; Liu, Y.S. The cognition and path analysis of rural revitalization theory based on rural resilience. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.G.; Yan, T.T. Types of the return migrations from mega-cities to local cities in China: A case study of Zhumadian’s return migrants. Geogr. Res. 2013, 32, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Qi, Y.; Cao, G. China’s floating population in the 21st century: Uneven landscape, influencing factors, and effects on urbanization. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2015, 70, 567–581. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, Y. Understanding and evaluating the resilience of rural human settlements with a social-ecological system framework: The case of Chongqing Municipality, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 136, 106966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.Z.; Yue, F.J.; Wei, B.H. The impacts of returning migrant labors on rural income inequality. Res. Agric. Mod. 2024, 45, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiba, M.; Collinson, M.; Hunter, L.; Twine, W. Social capital is subordinate to natural capital in buffering rural livelihoods from negative shocks: Insights from rural South Africa. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Migrant Workers Monitoring Survey Report in 2009. 2010-03-19. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2014-05/12/content_2677889.htm (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Migrant Workers Monitoring Survey Report in 2019. 2020-04-30. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sjfb/zxfb2020/202404/t20240430_1948783.html (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Niu, X.Y.; Liu, S.H.; Zhu, Y. Spatial characteristics of China’s urbanization: The perspective of inter-prefecture population movement. Urban Plan. Forum 2021, 1, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Putri, C.T.; Wardiyanto, B.; Suaedi, F. Policy evaluation of village fund through an agro-tourism village for sustainable local development. Masy. Kebud. Dan Polit. 2020, 33, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.F.; Zou, Y.F.; Yi, C.F.; Luo, F.; Song, Y.; Wu, P.Q. Optimization of rural settlements based on rural revitalization elements and rural residents’ social mobility: A case study of a township in western China. Habitat Int. 2023, 137, 102851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendall, M.S.; Parker, S.W. Two decades of negative educational selectivity of Mexican migrants to the United States. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2014, 40, 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.J.; Zhang, F.; Hu, L.X.; Zhao, H. Theoretical and empirical research on the impact of industrial and commercial capital on the improvement of rural residential environment. Resour. Sci. 2024, 46, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjaastad, L.A. The costs and returns of human migration. J. Political Econ. 1962, 70, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, H.; Stark, O. The Migration of Labor. Int. Migr. Rev. 1992, 26, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.Q.; Chen, X.H.; Li, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.H. The robustness mechanism of the rural social-ecological system in response to the impact of urbanization——Evidence from irrigation commons in China. World Dev. 2024, 178, 106565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafingi, H.M.; Dewi DA, S.; Suharso, H.; Sulistyaningsih, P.; Rahmawati, U. Village fund optimization strategy for rural community welfare in Indonesia. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 580–583. [Google Scholar]

- Tilahun, M.; Maertens, M.; Deckers, J.; Muys, B.; Mathijs, E. Impact of membership in frankincense cooperative firms on rural income and poverty in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 62, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M.P. A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.H.; Su, Y.Q.; Araral, E.K. Migration and collective action in the commons: Application of social-ecological system framework with evidence from China. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Nasrullah, M.; Zhang, R. Does social capital influence farmers’e-commerce entrepreneurship? China’s regional evidence. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Sannigrahi, S.; Bilsborrow, R.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D.; Li, J.; Song, C. Role of social networks in building household livelihood resilience under payments for ecosystem services programs in a poor rural community in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 86, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A.; Schermer, M.; Stotten, R. The resilience and vulnerability of remote mountain communities: The case of Vent, Austrian Alps. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. The impact of government basic public services and livelihood capital on the livelihood strategies of rural migrant labor. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Soc. Sci. 2023, 43, 55–73+146. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Li, H.M.; Zhang, L. Investigating the critical influencing factors of rural public services resilience in China: A grey relational analysis approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.K.; Ning, Y.M. Evolution of spatial pattern of inter-provincial migration and its impacts on urbanization in China. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 1492–1506. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, Y.D.; Hu, R.F. Does the return of migrant workers improve agricultural production efficiency? Taking 1,122 rice farmers in the Yangtze River Basin as an example. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2023, 60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Z.; Li, Q.C.; Huang, Z.H. The impact of kinship network on peasants’ tourism entrepreneurial intention based on a sample of Pujiang County, Zhejiang Province. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2019, 39, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.C.; Tang, S.S.; Huang, G.Z. Return decision-making mechanism of Chinese rural migrants from the perspective of assemblage theory: A case study of Yangzhou, Jiangsu province. Geogr. Res. 2024, 43, 1750–1768. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, W.H.; Lan, H.L. Why do Chinese enterprises completely acquire foreign high-tech enterprises—A fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) based on 94 cases. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 4, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Du, Y.Z. Application of QCA method in organization and management research: Positioning, strategy and direction. J. Manag. 2019, 16, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.Y.; Bao, H.X.H.; Yao, S.R. Unpacking the effects of rural homestead development rights reform on rural revitalization in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 108, 103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Korkmaz, A.G.; Ding, X.; Yue, P. Mirroring the urban exodus: The impact of return migration on rural entrepreneurship. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 66, 105619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, L. Influence of perceived value of rural labour in China on the labourers’ willingness to return to their hometown: The moderating effect of social support. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2024, 22, 2303892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antecedent Conditions | High Return Migration Rate | Non-High Return Migration Rate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |

| Natural capital |  |  |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |  |  | ⬤ | |

| Economic capital |  |  |  | ⬤ | ● | ● |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| Physical capital |  |  | ⬤ | ● |  |  | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |

| Human capital |  | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ |  |  |  | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| Social capital |  | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |  |  |  |  |  |

| Public infrastructure providers | ⬤ |  | ⬤ |  | ● |  |  |  | |

| Consistency | 0.851 | 0.840 | 0.864 | 0.858 | 0.859 | 0.883 | 0.834 | 0.839 | 0.813 |

| Raw coverage | 0.067 | 0.070 | 0.073 | 0.055 | 0.103 | 0.071 | 0.084 | 0.062 | 0.054 |

| Unique coverage | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.030 | 0.039 | 0.004 | 0.054 | 0.034 | 0.029 |

| Solution consistency | 0.836 | 0.841 | |||||||

| Solution coverage | 0.189 | 0.246 | |||||||

= core condition does not exist; ● = marginal condition exists;

= core condition does not exist; ● = marginal condition exists;  = marginal condition does not exist; Blank = condition dispensable.

= marginal condition does not exist; Blank = condition dispensable.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhang, X. How Does Rural Resilience Affect Return Migration: Evidence from Frontier Regions in China. Systems 2025, 13, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13020089

Su Y, Hu M, Zhang X. How Does Rural Resilience Affect Return Migration: Evidence from Frontier Regions in China. Systems. 2025; 13(2):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13020089

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Yiqing, Meiqi Hu, and Xiaoyin Zhang. 2025. "How Does Rural Resilience Affect Return Migration: Evidence from Frontier Regions in China" Systems 13, no. 2: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13020089

APA StyleSu, Y., Hu, M., & Zhang, X. (2025). How Does Rural Resilience Affect Return Migration: Evidence from Frontier Regions in China. Systems, 13(2), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13020089