Abstract

Today’s globalized economic system and the growing competition for human talent worldwide will test university graduates’ competencies to perform jobs that do not yet exist. Positioned as a catalyst for project-based entrepreneurial learning, Business Plan Competitions (BPCs) serve as a valuable learning experience that effectively prepares students for the interrelated systems of the 21st century, which are complementary and contradictory. The research objective was to evaluate key factors that enhance BPC participants’ competency utilization and overall success by exploring winners and non-winners’ cognitive abilities, personal traits, and occupational interests. Statistically significant results were found for Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional stability, and General learning ability, with higher averages observed among winners. Additionally, alongside General learning ability, Social interest emerged as predictors of performance in the BPC. Our study advances knowledge in entrepreneurial education research by applying systems thinking to foster its efficacy, with a competency development focus. The results can practically guide educators and policymakers in designing and implementing improved project-based entrepreneurial education programs.

1. Introduction

Today’s graduates enter the workforce in a disrupted economic, cultural, and social world, facing numerous systemic problems that require systemic solutions, such as reframing education using innovative educational programs to raise learners’ aspirations []. By placing the learner within a dynamic learning system replicating the dynamics and energy flows of real-world entrepreneurial ecosystems, project-based entrepreneurial education programs have flourished in universities worldwide [,,]. According to Obschonka et al. [] (p. 488), “entrepreneurial thinking and acting are seen as twenty-first-century skills, one of the basic meta-capabilities that the young generation will need to develop to be successful in life”. This meta-capability includes a range of transferable science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics abilities such as novel and adaptive thinking, problem-solving, collaboration and communication, creativity, and innovation [], all of which are valued as essential 21st-century skills [].

The existing literature points out that entrepreneurial education has the potential to help youth to gain 21st-century skills [,]. Addressing the convergence between entrepreneurship education in higher education institutions and 21st-century skills, Ghafar [] highlights that students’ exposure to interactive and experiential experiences contributes to developing social relationships, leadership, creativity, and critical thinking. Furthermore, Gatta [] found that 21st-century skills such as creativity, communication, risk management, and digital marketing skills have been strengthened by entrepreneurship education among business students. However, the relationship between 21st-century skills and entrepreneurship education using a systemic approach is yet to be thoroughly inspected [].

First, a student engaged in learning about entrepreneurship within a project finalized with a Business Plan Competition (BPC) is an individual with economic, sociological, psychological, behavioral, and managerial characteristics who operates within a contextual work environment composed of interrelated systems and is susceptible to developing important 21st-century skills such as time management, problem-solving, communication skills, and brainstorming, as Raveendra et al. pointed out []. Second, through BPCs, individuals are pushed to focus on proving the viability of their business idea in front of peers and evaluators, contributing to the strengthening of persuasion, commitment, and values, and the evolution of new perspectives, competencies, and attitudes [,,]. Moreover, as catalysts for project-based entrepreneurial learning, BPCs foster creativity and problem-solving skills by challenging participants to think innovatively, identify and address real-world problems, and collaboratively develop strategic and feasible solutions []. Given the existing literature on entrepreneurship education focused on the transitional countries of Central and Eastern Europe [], particularly for non-business students [,], we note a lack of empirical studies on the characteristics of BPC non-business students and their relationship with 21st-century skills. BPC participants are expected to demonstrate that performance is, in fact, a competition of achieved competencies or skills as entrepreneurial learning outcomes [], adding value to investments in project-based entrepreneurial education by addressing students’ mindsets shaped by cognitive abilities, personality traits, and occupational interests [,].

Addressing this research gap, we examined data from two groups of non-economic students (winners and non-winners) participating in the BPC organized within the cross-campus entrepreneurial program financed by the European Social Fund and overseen by the University of Oradea, Romania, spanning from May 2019 to June 2021. The objective of the research was to evaluate key factors that enhance BPC participants’ competency utilization and overall success by exploring their cognitive abilities, personal traits, and occupational interests. Accordingly, the main objective was divided into the following sub-objectives: (1) to identify the key factors that enhance competency utilization in the two groups of non-business students (winners and non-winners), (2) to determine the main predictors of BPCs‘ performance, and (3) to propose recommendations for a meritocratic 21st-century project-oriented entrepreneurial education programs. Students’ cognitive abilities, personal traits, and occupational interests were tested using the Cognitrom Assessment System (CAS) testing platform [] and performance obtained in BPCs with a 100-point scale, where higher scores typically indicate better performance or understanding of the assessed criteria. To this end, we fitted a regression model to explain group differences in performance. Our results showed that Social interest and General learning ability predict performance.

This paper thus contributes to addressing the 21st-century competency challenge by embedding a systemic approach in a dynamic and open meritocratic educational environment, such as project-based entrepreneurial programs. It also builds knowledge regarding BPCs’ role in supporting determinants of performance with practical implications for university educators, employers, and policymakers worldwide. At the same time, this study represents a pioneering effort to support the value of a systemic approach to designing and implementing a meritocratic project-based entrepreneurial education.

Following this introduction, the text is structured into five subsequent sections. First, we have a section providing the study’s theoretical background, followed by one that presents the materials and methods. The third section provides an overview of the results, while the fourth discusses them. In the fifth section, we present the conclusions of the study.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Study Context and Overview

Globally, there has been a significant increase in the youth population engaged in some form of schooling or training, rising from 38 percent in 2000 to 48 percent in 2023 []. However, this increase in educational participation is accompanied by a widening gap in skill levels among young adults across different countries [], particularly within middle- and low-income groups, such as in Romania. The disparities between the competencies required by employers and those acquired by university graduates, as highlighted in the literature [], make entrepreneurial education programs increasingly appealing to non-business students. These programs can equip individuals with the abilities and mindset necessary to navigate the transition from university to the labor market in complex and uncertain conditions, as well as to address the evolving demand for job-related skills [,,]. Exposure to entrepreneurial education not only triggers skill learning but also nurtures the social mission as one of the main dimensions of entrepreneurial motivation in Central and Eastern European countries, including Romania, as Bartha, Gubik, and Bereczk pointed out [].

Specifically, Papagiannis [] emphasizes the contribution of competitions organized within entrepreneurial education programs to forming an entrepreneurial mindset. This entrepreneurial mindset, deepened by valuable entrepreneurial learning experiences, has the potential to help university graduates thrive in the face of increasing challenges, such as the impact of artificial intelligence technology on employment []. To fully leverage entrepreneurial learning, universities support different curricular and extracurricular activities, including participation in Business Plan Competitions (BPCs) [] and student clubs’ involvement []. Mainly, Watson et al. [] found that at the start of a BPC, participation was viewed as a valuable experiential learning opportunity to meet the demands of the new world. By the end of the competition, participants felt that their experience had allowed them to develop their presentation, networking, and business plan creation abilities, and increased their confidence. Six months after the competition, participants continued recognizing that their abilities had been enhanced. In addition, Huang et al. [] explain the differences in benefits among BPC participants concerning entrepreneurial cognitive and non-cognitive competencies by using entrepreneurial spirit and entrepreneurship practice as moderators.

Despite the apparent straightforwardness of the positive association between BPCs and participants’ competency development, to our knowledge, studies that have specifically examined the differences among BPC participants from a systemic approach perspective are scarce.

2.2. The Need for a Systemic Approach

The environment in which a young individual is expected to perform, based on their achieved entrepreneurial competencies, is approached mainly in the literature from a systems thinking perspective (e.g., Lynch, Andersson, and Johansen []). Entrepreneurs must now understand and navigate complex systems, from supply chains and stakeholder networks to cultural and regulatory environments, all while leveraging the opportunities presented by advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things (IoT), and blockchain. Systems thinking [,] provides the tools and frameworks necessary for comprehending and addressing such complexities, enabling entrepreneurs to recognize interdependencies, anticipate consequences, adapt and innovate, and foster resilience []. This perspective is shaped by technological and social changes in a globalized world where economic, sociological, psychological, and managerial factors intertwine across different spheres of life []. An analysis of project-based entrepreneurial education’s key performance factors should integrate the participants’ generic and specific capabilities through the lens of their interplay within the environment. It is well known that the environment is a complex system, and in any complex system, the interactions between components are not linear or straightforward []; instead, they produce emergent behaviors influenced by people’s knowledge and attitudes [].

Entrepreneurial education literature typically approaches such interactions through deterministic methods [,]. These deterministic approaches focus on reducing systems to their parts, assuming that if individual components can be understood and improved, these improvements will enhance the overall system. For example, focusing on the role of digital technologies in rethinking entrepreneurial education helps improve performance in technique and skills development []. However, this determinist approach has reached its limits in adapting entrepreneurial education to Society 4.0, which is confronted mainly with complexity and uncertainty.

By contrast, from a systems thinking perspective, we can rethink the entrepreneurial education system to offer specific competencies and educate people who can become proactive seekers of opportunities. These individuals should possess an entrepreneurial mindset, knowing how to build their niche, engage themselves, and engage others to capitalize on the opportunities discovered. From this viewpoint, according to Von Bertalanffy [] and Meadows [], interventions at higher levels of entrepreneurial education systems are where the most significant positive systemic change can be leveraged. Entrepreneurial education has historically emphasized skills such as opportunity recognition, business planning, and financial perspicacity. While these remain important, they are insufficient for preparing individuals to thrive in environments characterized by complexity, uncertainty, and rapid change. Since BPCs are primarily recognized as substantial events at the top of the entrepreneurial education system, a study focusing on their participants, including the top performers, could significantly enhance their commitment to perceiving meaningful effort–effect relationships. These also include those that are indirect or separated in time and space from the entrepreneurial events they experience. In this way, the value of entrepreneurial education can be assessed by its application across all of society’s social subsystems, harnessing human and social capital skills vital for innovation and cross-sectoral cooperation in the 21st century []. Critics of “academia’s conceptual ethnocentrism” [] highlight the narrow focus on financial gain and suggest that BPCs, as tools traditionally rooted in financial objectives, may be misaligned with the deeper motivations of aspiring entrepreneurs, such us freedom, challenge, and purpose rather than financial rewards [,], and raise questions about their effectiveness in entrepreneurial education. On the other hand, since conventional education appears to be very vulnerable amidst a “moral desert” [], an emerging body of literature and research approaches focused on the values of competence and excellence question the meritocratic principles (e.g., Torres and Quaresma []) as an essential part of the rethinking mission of the educational system.

In summary, we propose to inquire into BPCs and their winners through a broader approach offered by the systems thinking literature, which possesses the potential to better rethink entrepreneurial education based on students’ proven cognitive and non-cognitive competencies.

2.3. Theoretical Basis

The theoretical basis of this study is formed by Gary Becker’s Human Capital Theory (HCT) [], Albert Bandura’s Social Cognitive Learning Theory (SCLT) [], and Signaling Theory (ST) [,].

Human capital is understood as a person’s propensity to perform behavior valued from an income-earning perspective [] (p. 31). According to HCT, education in general, and entrepreneurial education in particular, represents an investment in skills []. Many scholars emphasize the value embedded in skills, knowledge, and other attributes that enhance an individual’s ability to successfully engage in professional and civic life []. For example, Martin, McNally, and Kay [] pointed out that individuals with greater knowledge and skills achieve superior performance outcomes. To Rubin [], competition is an essential part of educational management that contributes to competency enhancement [], which in turn fosters self-efficacy in individuals and further develops human capital [].

According to SCLT, individuals learn from their interactions within a social context, a critical variable that impacts competency development []. In the case of entrepreneurial education for non-business students, as highlighted in the systematic literature review by Rocha, do Paço, and Alves [], the entrepreneurial ecosystem acts as a social learning environment enhancing cognition and providing valuable advantages, such as inspiration and resources []. Exposure to entrepreneurial role models, particularly parents and relatives, impacts entrepreneurial passion [] and influences individuals’ attitudes toward self-employment and decision-making about entrepreneurial intentions []. Essentially, SCLT posits that individuals acquire knowledge through observation, imitation, and the influence of institutions, learning either vicariously,—by observing role models—or directly—by actively participating in activities []. Providing entrepreneurial experiences such as BPCs emphasizes abilities that can be learned and further fosters cognitive and non-cognitive abilities [,,].

ST developed by Spence [] and improved by Stiglitz [] suggests that project-based entrepreneurial education, and its embedded BPCs as substantial events situated at the top of its system, serve as an effective method for participants, and especially for the top performers, to inform potential employers of their pre-existing competencies and personal characteristics [].

From this point of view, project-based entrepreneurial education contributes to society and all its related systems by enhancing graduates’ cognitive and non-cognitive entrepreneurial competencies to face changes in the 21st-century integrated economic and social systems.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Variables

Scientific discussions argue that exploring excellence in entrepreneurial education means examining the characteristics of the most accomplished educated individuals []. Traditionally, the study of individual performance differences has focused on two domains: personality and cognitive ability []. In light of systems thinking, performant project-based entrepreneurial education emphasizes the importance of understanding the “wholeness” of the entrepreneurial mindset, which is shaped by personality, cognitive abilities, and occupational interests [,,,].

3.1.1. Cognitive Abilities

There is ample evidence that cognitive abilities significantly impact economic and social outcomes (e.g., Borghans et al., []). Gottfredson [] (p. 13) defined cognitive ability or intelligence as “a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience”. According to Schneider and McGrew [], the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory of cognitive abilities posits that intelligence comprises a general cognitive capacity underlying all intellectual tasks and specific abilities tailored to each task.

Based on previous research that highlighted that individuals with higher cognitive abilities can adapt effectively to socioeconomic environments, such as entrepreneurial ecosystems, and overcome challenges through thoughtful consideration, a positive relationship between individuals’ cognitive capacities and their performance in BPCs can be anticipated. Furthermore, these individuals may be expected to engage in various forms of economic, social, and cultural reasoning when confronted with more intricate tasks than those with fewer cognitive abilities. Entrepreneurial literature (e.g., Jardim, Bártolo, and Pinho []) acknowledges the significance of General learning ability and Decision-making capacity in processing information, learning, and navigating unpredictable environments, ultimately facilitating problem-solving. This capacity fosters an entrepreneurial mindset, which is presumed to deliver knowledge, skills, and attitudes, both in the field of personal efficiency and interpersonal relationships of the work role.

3.1.2. Personality Traits

Different scholars have examined the power of personality traits for predicting important life outcomes (e.g., Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, and Goldberg []). As is well known, personality traits represent characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling, or behaving that tend to be consistent over time and across relevant situations. The most widely used model of personality is represented by a set of five trait dimensions, namely the Big Five, including “Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism (or Emotional stability), and Openness to experience” [] (p. 14). Following Goldberg [], the Big Five personality traits can capture a broad range of an individual’s personality due to the stability and comprehensiveness of the scale by which these traits are measured.

The importance of the Big Five traits is less examined in the context of entrepreneurial education than in entrepreneurship or education. However, the literature provides important arguments regarding their inclusion in our study. An important argument is supplied by Zhao et al. [], who have shown that the Big Five traits together explain 37% of a person’s entrepreneurial status. More relevant to our study, Zhao and Seibert [] demonstrated that the Big Five play an important role in entrepreneurial success, especially through conscientiousness and openness to experience. In an educational context, a recent meta-analysis [] further highlights that the Big Five traits relate to academic performance. Specifically, conscientiousness is a robust predictor of student performance that explains performance beyond cognitive ability. Openness to experience, even a weak predictor, also influences students’ performance. In this investigation, we build upon the reported findings and assume a direct link between the Big Five traits and the performance of BPC participants.

3.1.3. Occupational Interests

Interest describes how individuals engage with content or activities, such as entrepreneurial learning, and can be perceived in relation to public perception in three ways: motivational, actional, and attitudinal []. According to Holland’s theory of vocational choice [], people are differentially attracted to occupations as a function of their interests. From the perspective of individual differences, entrepreneurial education views students as actors who score on occupational interests that may be characterized as a substructure of personality. Specifically, Portuguez Castro and Gómez Zermeño [] characterized university students’ interest as a psychosocial strength that shapes their entrepreneurial intention across economic, technological, and societal dimensions.

According to previous research, the occupational interests of non-business university students should be addressed through multiple components aligned with the goals of entrepreneurial education. These components include (1) an entrepreneurial component, which includes students’ preference for endeavors that offer autonomy and the opportunity to lead one’s own endeavors or coordinate group activities; (2) a social component, encompassing a leaning towards activities that necessitate personal connections, with a focus on understanding, learning, and personal development among individuals; and (3) a realistic component, demonstrating individuals’ inclination towards activities involving the manipulation of objects, machinery, and tools, as well as engaging in physical tasks [,,]. Exploring the occupational interests of students participating in the business plan competition about cognitive abilities and the Big Five personality traits is important because, taken together, they can provide us with a systemic vision of the skills, motivation, and dynamic particularities that determine student performance implications in BPCs due to entrepreneurial education.

Considering all the aspects mentioned above, in this study, we will explore the following research questions regarding the relationship between cognitive abilities, personality traits, and occupational interests in the case of non-business students as participants in the BPCs organized within our cross-campus entrepreneurial program:

RQ1.

Which specific cognitive abilities (General learning ability and Decision-making capacity), personality traits (Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional stability, and Openness to experience), and occupational interests (Entrepreneurial interest, Social interest, and Realistic interest) are associated with performance in the two groups of non-business student participants (winners and non-winners) in the BPC? We refrain from advancing specific hypotheses on which types of participants’ characteristics are associated with performance in the BPC. Instead, we favor an exploratory approach with respect to this research question.

RQ2.

How strong is the unique impact of the different types of participants’ characteristics on performance in BPC, and which are the best predictors?

3.2. Participants and Procedure

The participants in this study were non-economic students in the penultimate year of study involved in a cross-campus entrepreneurial education program funded by the European Social Fund and run by the University of Oradea, Romania, between May 2019 and June 2021. During the entrepreneurial education program, all 450 students from different study domains, such as engineering, computer sciences, architecture and planning, medicine, law, environmental sciences, social sciences, geography, and visual and performing arts, were tested for aptitudes using the Cognitrom Assessment System (CAS) testing platform [] and benefited from an entrepreneurial learning program that included developing a business plan. Approximately 50% of the students (n = 226) participated in the business plan competition, but only some won and received a cash prize (n = 113). Group 1 (winners) consisted of students who won an award in the business plan competition, and Group 2 (non-winners) was made up of students who did not win a prize in the business plan competition. Each group consisted of 113 students with similar demographic characteristics (gender, average age, environment of origin, and status in the labor market), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic sample group characteristics.

In our European-founded program, and implicitly in our study, participants were randomly selected to ensure that every individual had an equal chance to take part and, more importantly, to increase the generalizability of our study’s results. To reduce bias and to ensure that the results were valid and reliable, we considered demographic variables, including gender, age, the environment of origin, and status in the labor market, initially set for the project’s requirements. At this point, it is necessary to mention that, according to the rules in our project-based entrepreneurial programs, a minimum of 50% of participants (i.e., 225) must participate in the BPC, and furthermore, a minimum of 50% of BPC participants must receive an award. Consequently, in our study, the number of non-business students included in Group 1 (winners) is equal to the number of non-business students included in Group 2 (non-winners).

As can be seen in Table 1, the most significant difference in terms of socio-demographic characteristics between the two groups concerns gender. Thus, while in Group 1 (the winners), the percentage of women is 78.76%, in Group 2 (the non-winners), their percentage drops to 58.41%. Another noteworthy element is the slightly higher average age among the participants in Group 1, namely 24.34 years, compared to 23.52 years for those in Group 2.

3.3. Measures

The three key factors that enhance BPC participants’ skill utilization and overall success are cognitive abilities, personality traits, and occupational interests, which are also the independent variables of our study. Each of these factors includes sub-factors as follows: (1) Cognitive abilities include the sub-factors of General learning ability and Decision-making capacity; (2) Personality Traits, or the Big Five traits, include the sub-factors of Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, neuroticism (or Emotional stability), and Openness to experience; and (3) Occupational interests include the sub-factors of Entrepreneurial interest, Social interests, and Realistic interest. The three key factors and their sub-factors, along with the operationalized study instruments and descriptions, were measured using the Cognitrom Assessment System (CAS) testing platform [] and are presented in Appendix A.

Specifically, General learning ability and Decision-making capacity were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = very weak, 5 = very well); Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional stability, and Openness to experience were measured on a 0–100 scale (below 40 points = low scores, above 60 points = high scores), and Entrepreneurial interest, Social interest, and Realistic interest were measured on a 0–100 probability scale (0% = very low, 100% = very high).

The dependent variable, performance in the BPC, represents the overall average score obtained by the participants (100 points = excellent, 10 points = fail).

4. Results

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics, including minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation, for participants’ overall scores in the BPC. It also includes measures of cognitive abilities, personality traits, and occupational interests, which serve as variables to evaluate the performance of BPC participants.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the measured sub-factors of cognitive abilities, personal traits, occupational interests, and the overall score of the business plan.

The average scores for cognitive abilities fell within the range of 1 to 5. The results for its two sub-factors hover around the average values. Specifically, for the capacity to make decisions, m = 2.90 and s.d. = 1.069, and for General Learning Ability, m = 3.27 and s.d = 0.900. The average scores ranged between 0 and 93 for personality traits’ components. The lowest mean was obtained for extroversion (m = 49.08, s.d. = 12.492) and the highest for agreeableness (m = 57.80, s.d. = 10.444) and conscientiousness (m = 57.73, s.d. = 9.206). Regarding occupational interests, the average scores ranged between 0 and 100, with a higher average score for social interests (m = 80.87, s.d. = 17.791) and a lower one for realistic interests (m = 67.06, s.d. = 23.718). The outcome variable of this study (performance in BPC) had an m = 76.832 and an s.d. = 15.25. The lowest score was 50 points, and the highest was 100.

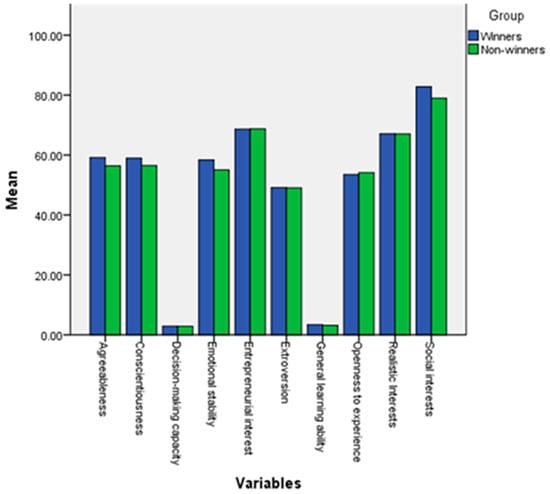

To enhance the clarity and visual representation of the statistical results, we present Bar Chart 1 (see Figure 1), which illustrates the mean scores for Group 1 (winners) and Group 2 (non-winners) across key variables, including Cognitive Abilities (General learning ability and Decision-making capacity), Personal Traits, (Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional stability, and Openness to experience), and Occupational Interests (Entrepreneurial interests, Social interests, and Realistic interests). This bar chart provides a clear and intuitive visualization of the differences between the two groups, complementing the detailed statistical data presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Bar Chart 1. Mean Scores for Group 1 (winners) and Group 2 (non-winners): Cognitive Abilities, Personal Traits, and Occupational Interests.

Table 3.

The independent t-test for the two categories of participants (non-winners vs. winners).

To compare the results obtained by Group 1 versus Group 2, we analyzed the data using the statistical package SPSS version 22.00, particularly the t-test for independent samples (see Table 3).

Statistically significant results were highlighted for three of the variables related to personality traits, with higher averages for winners than non-winners, as follows: (1) Agreeableness (t(224) = −2.027, p = 0.044 < 0.05, Levene test F = 3.28, p = 0.071 > 0.05, low Cohen effect size d = 0.134); (2) Conscientiousness (t(209,248) = 2.015, p = 0.045, Levene test F = 3.950, p = 0.048 < 0.05, low Cohen effect size d = 0.137); (3) Emotional stability (t(210,195) = 1.985, p = 0.048, Levene test F = 5.828, p = 0.017 < 0.05, low Cohen effect size d = 0.135). We can also speak of a tendency for the General learning ability variable to differ between the two groups, with higher averages for students from the winners’ category (t(224) = 1.934, p = 0.054, Levene test F = 1.592, p = 0.2088 > 0.05, low Cohen effect size d = 0.128). No statistically significant differences were obtained between the two groups for the other variables included in the study. In short, the results capture the variables that outline the personality traits included in the winner’s student profile: Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional stability, and a higher level of General learning ability.

To estimate by regression the future results of the criterion variable introduced in our study (i.e., the performance obtained in the business plan competition—BPC performance), we previously made the correlation matrix (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations between the criterion variable and the variables included as possible predictors.

The results indicate a positive association relationship between the score obtained for BPC performance and (a) General learning ability (r = 0.199, p = 0.003 < 0.05, low effect size r2 = 0.039) and (b) Social interests (r = 0.208, p = 0.002 < 0.05, low effect size r2 = 0.043). Resultantly, non-economic students with a high level of general learning skills and increased social interests will have an advantage in BPC performance. At this point, any conclusion must be cautiously formulated due to the low effect size. In the next phase, the linear regression analysis was used to measure the influence of the general level of learning ability and social interests on the Business Plan Overall Score. We specify that from a technical point of view, there were no special situations, and all the application conditions of the regression were supported. There were no multicollinearity problems, the VIF values obtained being 1.008 < 10, and those of the tolerance 0.992 > 0.20. Also, there were no unusual or extreme cases, with the standardized residuals having values between −2.022 and 1.869. Even checking the influential cases with the help of Cook’s distance, no values higher than 1 were revealed, which indicates the absence of such cases. The results of the linear regression analysis aimed at estimating the performance of students in BPCs based on the predictors considered in the study are presented (in summary) in Table 5.

Table 5.

The results of the linear regression analysis (n = 226)—summary.

The obtained results support the idea that both General learning ability and Social interest significantly influence performance in BPC (ΔR² = 0.068, F-change (2, 223) = 9.18, p < 0.01). Thus, the two factors explain 6.8% of the performance obtained when evaluating the business plans. One can say that students who have high social interests (β = 0.192, t = 2.967, p < 0.01) and have a high level of General learning skills (β = 0.182, t = 2.819, p < 0.01) achieve superior performance in their business plan evaluation. Analyzing the values of the semi-partial r coefficients, we can conclude that if we eliminate the influence of the other predictor, 3.6% (rpart = 0.191) of the dispersion of the performance in the realization of the business plan can be explained by the social interests of the students, and 3.2% (rpart = 0.181) by general learning skills. In brief, the findings highlight that, along with the general ability to learn, social interests are predictors of the performance achieved in BPC.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the influence of cognitive abilities, which include the sub-factors of general learning ability and decision-making capacity; personality traits, precisely, the Big Five traits, which include the sub-factors of extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism (or emotional stability), and openness to experience; and occupational interests, which include the sub-factors of entrepreneurial interest, social interest, and realistic interest on the performance obtained by non-business students in BPC. The findings suggest that a combination of Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional stability, General learning ability, and Social interest are essential in BPCs and improve performance.

Agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability are three personality traits that significantly contribute to success in BPC. Agreeableness, characterized by traits such as cooperation, empathy, and social harmony, helps individuals effectively present, argue, and sustain their business plan, and navigate the social dynamics, which are crucial in collaborative environments like BPC. Conscientiousness, on the other hand, involves being organized, diligent, and business objectives oriented. This trait ensures that individuals are thorough in their business planning, adhere to deadlines, and maintain a high level of commitment to their business plan. Furthermore, emotional stability fosters a balanced approach to both interpersonal interactions and task management, leading to higher chances of success in BPC. General learning ability also significantly contributes to success in BPC revealing an individual’s capacity to generate novel information, such as a new product or service by synthesizing existing knowledge. Moreover, this ability efficiently serves to solve problems, and to derive accurate conclusions, for example, from market analysis. Social interest is essential in BPC and improve participants` performance due to the fact that entrepreneurial programs better enhance the importance of intrinsic motivations, such as the social mission, than standard university programs.

It is difficult to compare these findings with previous studies because in the current study, we used an innovative approach, applying systems thinking to entrepreneurial education culminating with a BPC, which provides a broader and deeper understanding of how competencies are developed. However, the study’s results are consistent with various scholars’ findings on university students’ performance, including Fenollar, Román, and Cuestas [], who highlighted the key mediational role of study strategies in the effect of achievement goals and self-efficacy on academic performance. Gonzalez [] finds that using a strategy based on preparing for parallel research and BPCs significantly and positively impacts student engagement, developing skills such as perseverance, adaptability, and transferable STEAM skills. Additionally, the study aligns with Mammadov’s [] meta-analysis on the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and academic performance. It also resonates with Ou and Kim’s [] work on the catalytic role of psychology in entrepreneurship education in developing cognitive and emotional skills among college students. Furthermore, the study is in line with Portuguez Castro and Gómez Zermeño’s [] research on identifying interest and skills, as well as Renninger and Hidi’s [] findings on interest as a unique cognitive and affective motivational variable, which is crucial for developing latent skills. Additionally, Moore et al. [] pointed out that Agreeableness and Conscientiousness facilitate successful adaptation through effective internalization of guidelines. In the case of BPCs, successful adaptation is related to effectively internalizing BPC criteria and rules, a process that helps individuals align their behaviors and decisions with established standards, leading to better outcomes in challenging situations, such as those posed by BPCs.

The analysis in this research revealed that students with high social interests and a high level of General learning ability achieve superior performance. These findings are partially counter to those of Tan and Balasico [], who found that in the context of the National Career Assessment Examination (NCAE), students generally perform better in terms of general scholastic aptitude, which measures the knowledge that fourth-year high school students have already acquired. However, most students in the above-mentioned study did not have preferred occupational interests. We assume that this inconsistency arises from the different focuses of the studies. Our study focused on the performance assessment of non-economic students in the penultimate year of study who were involved in a project-based entrepreneurial education program. In contrast, Tan and Balasico [] focused on the national performance assessment of fourth-year high school students.

Meanwhile, it is worth noting that, going beyond previous studies that described the dynamics of applying project-based entrepreneurial learning to create startups in higher education institutions [], our study provides empirical evidence related to the positive impact of implementing project-based entrepreneurial learning and demonstrates the competences and excellence of BPC participants. In this line of thinking, our results align with Kongmanus [], who found that implementation stages such as exploring opportunities, selecting an idea, producing a plan, and presenting it improve students’ performance. By identifying General learning ability and Social interest as the main predictors of performance in the BPC organized in our project-based entrepreneurial learning program, we offer an empirically proven solution tailored to the needs of non-business students. This solution, called for by Sáfrányné Gubik and Farkas [], has the potential to be replicated in other countries, especially in Central and Eastern European countries.

6. Conclusions

We conducted an empirical study to develop a new understanding of BPC participants’ competencies and excellence within the framework of project-based entrepreneurial learning. We offer valuable insights using a less commonly used research approach, namely, a systemic approach. Systems thinking has emerged as an essential paradigm for entrepreneurial education, providing an approach that transcends conventional, linear models of teaching and learning. It offers a holistic perspective that aligns with the multifaceted challenges and interconnectedness any student faces today, driven by the convergence of physical, digital, and biological systems. Drawing on BPC data from winners and non-winners, and triangulating these data with archival materials related to these two groups, which were evaluated using the Cognitrom Assessment (CAS) testing platform for career counseling and guidance, and observations, we provide a comprehensive picture of how project-based entrepreneurial learning unfolds and is managed to achieve success.

Our paper contributes to the literature on entrepreneurial learning by extending the work of Santoso et al. [] and outlining the positive outcomes of project-based entrepreneurial learning. We also explore the BPC as a top event within the project-based entrepreneurial learning system and its participants, addressing the call to merge systems thinking with entrepreneurship by shifting students’ mindsets toward crafting a more sustainable future []. Going further, we demonstrate that two complementary yet contradictory but inseparable approaches in the organizational learning literature (i.e., exploitation that strengthens existing competencies and exploration that challenges new competencies) can enhance project-based entrepreneurial learning performance and challenge its sustainability with a mixed focus on competencies.

The results of this empirical study and the insights presented are considered particularly valuable for university educators and policymakers in designing and implementing more 21st-century-focused project-based entrepreneurial education programs. They offer an opportunity to acquire an in-depth and systemic understanding of the benefits of entrepreneurial education programs and the practical implications of BPCs as events that could help university educators implement an exploitation–exploration learning method in a dynamic environment. This method could aid in the development of existing and new competencies. Facing environmental dynamism, complexity, and uncertainty, universities may better address these challenges by reconciling exploitative and exploratory learning within project-based entrepreneurial education programs. Specifically, for universities, teachers, and tutors involved in teaching entrepreneurship, the results of our study suggest a direction in which they could focus their efforts to move entrepreneurial education for non-business students beyond its traditional focus on business plans or entrepreneurial intentions. For example, a series of pedagogical innovations could be anchored on the under-addressed dimensions of individual cognitive abilities, such as the general ability of learning, or on the socio-cognitive dynamics between students and other interested parties. This could be further enhanced by encouraging the development of personality traits such as agreeableness or conscientiousness, as well as by stimulating their social interests.

In addition to contributions, the study‘s limitations should be highlighted. First, our study data are limited geographically, as only university non-business students from Romania participated. Hence, the results from other countries might reveal further compelling aspects of BPC participants’ competencies and excellence within the framework of project-based entrepreneurial learning.

Second, we use self-reported measurements of research data, which can lead to biases and limit the generalizability of our study’s results. Although it would be difficult to ask coworkers or teachers involved in teaching entrepreneurship to evaluate a BPC participant on traits such as Agreeableness or Conscientiousness, future studies can reduce common biases by collecting data from different sources, such as participant–teacher or participant–tutor pairs. For example, General Ability of Learning and Conscientiousness can be measured through self-reports, while Agreeableness can be measured using data collected from teachers or tutors.

Third, the study focuses on the relationship between cognitive abilities, personality traits, occupational interests, and performance in BPCs, ignoring risk-taking propensity. Researchers (e.g., []) have pointed out that beyond the need for achievement, the propensity towards taking risks plays an important role in determining students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Especially considering the possibility that BPC winners with high scores in General learning ability and Social interest can become start-up entrepreneurs, future studies can achieve more generalizable results by including risk-taking propensity in the model.

Fourth, our study did not address an important demographic aspect of BPC participants: previous exposure to entrepreneurial education, such as in secondary school. Previous studies have revealed the moderating effect of entrepreneurial education on the relationship between psychological and behavioral traits and the entrepreneurial intentions of secondary students [,]. Therefore, previous exposure to entrepreneurial education can represent an important factor to be considered by futures studies.

Finally, future research could use a mixed approach, i.e., a quantitative–qualitative research method, to better address key factors that enhance BPC participants’ competency utilization and overall success by exploring the cognitive abilities, personal traits, and occupational interests of both winners and non-winners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.-A.B. and A.-O.D.; methodology, E.-A.B. and A.-O.D.; software, A.-F.B. and I.-C.P.-C.; validation, E.-A.B., A.-O.D. and A.-F.B.; formal analysis, E.-A.B., A.-O.D. and A.-F.B.; resources, E.-A.B., A.-O.D., A.-F.B. and I.-C.P.-C.; data curation, I.-C.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.-A.B.; writing—review and editing, E.-A.B., A.-O.D. and I.-C.P.-C.; supervision, E.-A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this non-interventional study, as participation was entirely voluntary and formally accepted by students through an official AntreV project document.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The project “Entrepreneur for the future” (AntreV), co-financed by the European Social Fund through the Human Capital Operational Programme 2014–2020, beneficiary: University of Oradea; total value: 7,282,442.22 lei; period of implementation: 24 May 2019–26 June 2021; web: https://antrev.uoradea.ro/ro/”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Key Factors and Sub-Factors Influencing BPC Participants’ Success: Operationalization and Study Instruments

Table A1.

Key factors and sub-factors influencing BPC participants’ success: operationalization and study instruments.

Table A1.

Key factors and sub-factors influencing BPC participants’ success: operationalization and study instruments.

| Key Factor | Sub-Factors | Instrument | Instrument Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive abilities | General learning ability | Analytical reasoning test | The assessment evaluates an individual’s capacity to generate novel information by synthesizing existing knowledge. The initial segment of the test evaluates the aptitude for identifying patterns and utilizing them to solve problems (i.e., inductive reasoning), while the subsequent segment gauges the ability to derive accurate conclusions from various statements (deductive reasoning). |

| Decision-making capacity | Decision-making capacity test | The test evaluates an individual’s capacity to make rational choices among multiple available options to resolve a situation or problem. | |

| Pesonality Traits | Extro version | Extroversion test | The test assesses variances in social involvement, assertiveness, and energy levels among individuals. Those with high extroversion typically thrive on social interactions, feel at ease expressing themselves in group settings, and often exhibit positive emotions like enthusiasm and excitement. Conversely, introverted individuals tend to be more reserved in social and emotional contexts. |

| Agreea bleness | Agreeableness test | Agreeableness encompasses variations in compassion, respectfulness, and acceptance towards others. Individuals high in agreeableness typically show emotional empathy for others’ welfare, treat them with consideration for their rights and preferences, and generally hold optimistic views about others. Conversely, individuals low in agreeableness often display less regard for others and for social norms of politeness. | |

| Conscien tiousness | Conscientiousness test | Conscientiousness reflects variances in organization, productivity, and accountability. Individuals with high conscientiousness value order and structure, consistently strive towards achieving their objectives, and demonstrate dedication to fulfilling their responsibilities. On the other hand, those low in conscientiousness tend to be more comfortable with disorder and exhibit less motivation to complete tasks. | |

| Emotional stability | Emotional stability test | Emotional stability delineates disparities in the frequency and intensity of negative emotions. Individuals low in emotional stability are susceptible to feelings of anxiety, sadness, and mood fluctuations, whereas those high in emotional stability typically maintain composure and resilience, even when facing challenging situations. | |

| Openness to experience | Openness to experience test | Openness to experience, often referred to as Intellect, encompasses variations in intellectual curiosity, aesthetic sensitivity, and imagination. Individuals high in openness delight in exploring new ideas and concepts, appreciate art and beauty, and possess a knack for generating original thoughts. Conversely, those low in openness tend to exhibit a more limited range of intellectual and creative interests. | |

| Entrepre neurial interest | Entrepreneurial interest test | Entrepreneurial interest is evidenced by a preference for endeavors that offer autonomy and the opportunity to lead one’s own initiatives or coordinate group activities, such as managerial or sales roles. Typically, individuals gravitate towards activities where they can exert influence, make decisions, and take risks, and are less inclined towards working with abstract ideas or engaging in scientific pursuits. | |

| Social interest | Social interest test | Social interest encompass a leaning towards activities that necessitate interpersonal connections, with a focus on understanding, learning, and personal development among individuals. This can include roles such as teaching, training, or providing assistance to aid individuals in resolving diverse problems. | |

| Realistic interest | Realistic interest test | Realistic interest is demonstrated by individuals’ inclination towards activities involving the manipulation of objects, machinery, and tools, as well as engaging in physical tasks. This may include pursuits within fields such as technology, automotive, or agriculture. |

Source: created by authors after [].

References

- Best, S. Reframing Education Failure and Aspiration: The Rise of the Meritocracy, 1st ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-4473-7496-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cheers, C.; Chen, S. Education for a World Disrupted. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN20, Online, 6–7 July 2020; pp. 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodescu, A.-O.; Botezat, E.-A.; Constăngioară, A.; Pop-Cohuţ, I.-C. A Partial Least-Square Mediation Analysis of the Contribution of Cross-Campus Entrepreneurship Education to Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, K.; Dodescu, A.O.; Botezat, E.A.; Pop-Cohut, I.C. Designing and Delivering a Cross-Campus Entrepreneurship Education Program. Rev. Rom. Educ. Multidimens. 2024, 16, 71–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, M.; Hakkarainen, K.; Lonka, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Entrepreneurship as a Twenty-First Century Skill: Entrepreneurial Alertness and Intention in the Transition to Adulthood. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 48, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.G.; Namukasa, I.K. STEAM Education: Student Learning and Transferable Skills. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2020, 13, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakowska, A.; de Juana-Espinosa, S.; Trunk, A.; Dawson, D. Ready for the Future? Employability Skills and Competencies in the Twenty-First Century: The View of International Experts. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2021, 40, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pablo, J.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Ruiz Real, J. Entrepreneurship and Education in the 21st Century: Analysis and Trends in Research. J. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lackéus, M. Entrepreneurship in Education. What, Why, When, How; Entrepreneurship 360; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ghafar, A. Convergence between 21st Century Skills and Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education Institutes. Int. J. High. Educ. 2020, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatta, S.A.; Ishola, N.A.; Falobi, O.V. Evaluation of Business Education Curriculum and 21st Century Entrepreneurial Skills in Business Education Undergraduates Students. ASEAN J. Econ. Econ. Educ. 2023, 2, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Raveendra, P.V.; Rizwana, M.; Singh, P.; Satish, Y.M.; Kumar, S.S. Entrepreneurship Development through Industry Institute Collaboration: An Observation. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2020, 9, 980–984. [Google Scholar]

- Banha, F.; Coelho, L.S.; Flores, A. Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Literature Review and Identification of an Existing Gap in the Field. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.-P.; Crocco, E.; Culasso, F.; Giacosa, E. Business Plan Competitions and Nascent Entrepreneurs: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 863–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csákné Filep, J.; Timár, G.; Szennay, Á. Analysing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Early-Stage Entrepreneurship—Focusing on the Transitional Countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.G.; do Paço, A.; Alves, H. Entrepreneurship Education for Non-Business Students: A Social Learning Perspective. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.; Atchison, M.; Brooks, R. Business Plan Competitions in Tertiary Institutions: Encouraging Entrepreneurship Education. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2008, 30, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, N.; Phipps, D.; Provencal, J.; Hewitt, A. Knowledge Mobilization, Collaboration, and Social Innovation: Leveraging Investments in Higher Education. Can. J. Nonprofit Soc. Econ. Res. 2013, 4, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Y.; Lednev, M.; Mozhzhukhin, D. Competition Competencies as Learning Outcomes in Bachelor’s Degree Entrepreneurship Programs. J. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, M.; Andersson, G.; Johansen, F.R. Merging Systems Thinking with Entrepreneurship: Shifting Students’ Mindsets towards Crafting a More Sustainable Future. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclea, M.; Porumb, M.; Cotârle, P.; Albu, M. CAS++—Cognitrom Assessment System, Revised 2nd ed.; ASCR: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Global Employment Trends for Youth 2024. Decent Work, Brighter Futures; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Apunyo, R.; White, H.; Otike, C.; Katairo, T.; Puerto, S.; Gardiner, D.; Kinengyere, A.A.; Eyers, J.; Saran, A.; Obuku, E.A. Interventions to Increase Youth Employment: An Evidence and Gap Map. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazíková, J.; Takáč, I.; Rumanovská, Ľ.; Michalička, T.; Palko, M. Which Skills Are the Most Absent among University Graduates in the Labour Market? Evidence from Slovakia. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosemans, I.; Coertjens, L.; Kyndt, E. Exploring Learning and Fit in the Transition from Higher Education to the Labour Market: A Systematic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 21, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botezat, E.-A.; Constăngioară, A.; Dodescu, A.-O.; Pop-Cohuţ, I.-C. How Stable Are Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context? Sustainability 2022, 14, 5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, Z.; Gubik, A.S.; Bereczk, A. The Social Dimension of the Entrepreneurial Motivation in the Central and Eastern European Countries. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 7, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannis, G.D. Entrepreneurship Education Programs: The Contribution of Courses, Seminars and Competitions to Entrepreneurial Activity Decision and to Entrepreneurial Spirit and Mindset of Young People in Greece. J. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 21, 1–132. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, X. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employment: The Role of Virtual Agglomeration. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licha, J.; Brem, A. Entrepreneurship Education in Europe—Insights from Germany and Denmark. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2018, 33, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, L.A.; Gazzard, J.; Shore, A.; Williamson, T. Student Clubs: Experiences in Entrepreneurial Learning. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2015, 27, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; McGowan, P.; Cunningham, J.A. An Exploration of the Business Plan Competition as a Methodology for Effective Nascent Entrepreneurial Learning. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; An, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, P. The Role of Entrepreneurship Policy in College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention: The Intermediary Role of Entrepreneurial Practice and Entrepreneurial Spirit. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 585698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; G. Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1973; ISBN 978-0-8076-0452-6. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-60358-055-7. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. Dynamic Capabilities as (Workable) Management Systems Theory. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, C.; Misra, S. Relevance of Systems Thinking and Scientific Holism to Social Entrepreneurship. J. Entrep. 2015, 24, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, H.; Greene, P. Entrepreneurship Education: Known Worlds and New Frontiers. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 49, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukul, E.; Büyüközkan, G. Digital Transformation in Education: A Systematic Review of Education 4.0. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 194, 122664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primario, S.; Rippa, P.; Secundo, G. Rethinking Entrepreneurial Education: The Role of Digital Technologies to Assess Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Intention of STEM Students. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 2829–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Srivastava, S.; Bindra, S.; Sangwan, S. An Ecosystem View of Social Entrepreneurship through the Perspective of Systems Thinking. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2023, 40, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Slåttsveen, K.; Lozano, F.; Steinert, M.; Andersson, G. Examining Entrepreneurial Motivations in an Education Context. In DS 87-9 Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 17) Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 August 2017; Design Society: Glasgow, UK, 2017; Volume 9, pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Napoletano, T. Meritocracy, Meritocratic Education, and Equality of Opportunity. Theory Res. Educ. 2024, 22, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Quaresma, M. The Meritocratic Ideal in Education Systems: The Mechanisms of Academic Distinction in the International Context. Educ. Chang. 2017, 21, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Front Matter, Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. In Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, 2nd ed.; NBER: Chicago, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; pp. xiii, 617. ISBN 978-0-13-815614-5. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. The Theory of “Screening,” Education, and the Distribution of Income. Am. Econ. Rev. 1975, 65, 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Hunter, A. Women Entrepreneurs Across Racial Lines: Issues of Human Capital, Financial Capital and Network Structures; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-84376-416-8. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education, 3rd ed.; NBER Books: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- González-Pérez, L.I.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.S. Components of Education 4.0 in 21st Century Skills Frameworks: Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.C.; McNally, J.J.; Kay, M.J. Examining the Formation of Human Capital in Entrepreneurship: A Meta-Analysis of Entrepreneurship Education Outcomes. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L. Spurring Inclusive Entrepreneurship and Student Development Post-C19: Synergies between Research and Business Plan Competitions. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2021, 15, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Toward a Psychology of Human Agency: Pathways and Reflections. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadayon Nabavi, R.; Bijandi, M. Bandura’s Social Learning Theory & Social Cognitive Learning Theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 1, 589. [Google Scholar]

- Türk, S.; Zapkau, F.B.; Schwens, C. Prior Entrepreneurial Exposure and the Emergence of Entrepreneurial Passion: The Moderating Role of Learning Orientation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 225–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Domitrovich, C.E.; Weissberg, R.P.; Gullotta, T.P. Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4625-2017-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazarian, P. Signaling Value of Education. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Economics and Society; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4522-2643-9. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, A.; Wilson, R. A Systematic Review Looking at the Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on Higher Education Student. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, V.J. Personality and Cognitive Abilities. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-3-319-28099-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bergner, S. Being Smart Is Not Enough: Personality Traits and Vocational Interests Incrementally Predict Intention, Status and Success of Leaders and Entrepreneurs Beyond Cognitive Ability. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daradkeh, M. Navigating the Complexity of Entrepreneurial Ethics: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Kim, K. Integrating Psychology into Entrepreneurship Education: A Catalyst for Developing Cognitive and Emotional Skills Among College Students. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghans, L.; Duckworth, A.L.; Heckman, J.J.; Ter Weel, B. The Economics and Psychology of Personality Traits. J. Hum. Resour. 2008, 43, 972–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, G.D. Career Stability and Redirection in Adulthood. J. Appl. Psychol. 1977, 62, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.J.; McGrew, K.S. The Cattell–Horn–Carroll Theory of Cognitive Abilities. In Contemporary Intellectual Assessment: Theories, Tests, and Issues, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 73–163. ISBN 978-1-4625-3578-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jardim, J.; Bártolo, A.; Pinho, A. Towards a Global Entrepreneurial Culture: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Kuncel, N.R.; Shiner, R.; Caspi, A.; Goldberg, L.R. The Power of Personality: The Comparative Validity of Personality Traits, Socioeconomic Status, and Cognitive Ability for Predicting Important Life Outcomes. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, O.P.; Naumann, L.P.; Soto, C.J. Paradigm Shift to the Integrative Big Five Trait Taxonomy: History, Measurement, and Conceptual Issues. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 114–158. ISBN 978-1-59385-836-0. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L.R. The Structure of Phenotypic Personality Traits. Am. Psychol. 1993, 48, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E. The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Entrepreneurial Status: A Meta-Analytical Review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadov, S. Big Five Personality Traits and Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis. J. Personal. 2022, 90, 222–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roco, M.; Bainbridge, W. Nanotechnology: Societal Implications—II. Individual Perspectives; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; ISBN 978-1-4020-4658-2. [Google Scholar]

- Spokane, A.R. A Review of Research on Person–Environment Congruence in Holland’s Theory of Careers. J. Vocat. Behav. 1985, 26, 306–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portuguez Castro, M.; Gómez Zermeño, M.G. Identifying Entrepreneurial Interest and Skills among University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.A.; Balasico, C.L. Students’ Academic Performance, Aptitude and Occupational Interest in the National Career Assessment Examination. PUPIL Int. J. Teach. Educ. Learn. 2018, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renninger, K.A.; Hidi, S.E. Chapter Six—Interest: A Unique Affective and Cognitive Motivational Variable That Develops. In Advances in Motivation Science; Elliot, A.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 9, pp. 179–239. ISBN 978-0-12-818630-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fenollar, P.; Román, S.; Cuestas, P.J. University Students’ Academic Performance: An Integrative Conceptual Framework and Empirical Analysis. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 77, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.M.; Holding, A.C.; Levine, S.; Powers, T.; Koestner, R. Agreeableness and Conscientiousness Promote Successful Adaptation to the Covid-19 Pandemic through Effective Internalization of Public Health Guidelines. Motiv. Emot. 2022, 46, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, R.T.P.B.; Priyanto, S.H.; Junaedi, I.W.R.; Santoso, D.S.S.; Sunaryanto, L.T. Project-Based Entrepreneurial Learning (PBEL): A Blended Model for Startup Creations at Higher Education Institutions. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongmanus, K. Development of Project-Based Learning Model to Enhance Educational Media Business Ability for Undergraduate Students in Educational Technology and Communications Program. J. Adv. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sáfrányné Gubik, A.S.; Farkas, S. Entrepreneurial Intention in the Visegrad Countries. Danube 2019, 10, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.; Bostan, I.; Robu, I.-B.; Maxim, A.; Diaconu (Maxim), L. An Analysis of the Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intentions among Students: A Romanian Case Study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furdui, A.; Lupu-Dima, L.; Edelhauser, E. Implications of Entrepreneurial Intentions of Romanian Secondary Education Students, over the Romanian Business Market Development. Processes 2021, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilar, W.; Rachwał, T. Changes in Entrepreneurship Education in Secondary School under Curriculum Reform in Poland. J. Intercult. Manag. 2019, 11, 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).