Abstract

Recent research reflects the assessment of customer satisfaction from different perspectives, an important aspect in all sectors that must be expressed in measurable parameters of organization performance. By reviewing the literature, we noticed the lack of a specific indicator to quantify the tripartite relation: customer satisfaction—employee performance—company performance. Therefore, based on Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma methods, the paper introduces an innovative measurement tool named the Spc indicator (The Assessment System of Employee Performance according to Customer Satisfaction) and the related implementation methodology (named ITA). The aim of the paper is to implement an innovative tool to improve the efficiency of employee performance assessment systems in relation to company performance in services and industry sectors through customer satisfaction assessment. By using AR and VR as implementation technologies, our present results extend and compare the results from other pilot research made by authors in the e-commerce sector. The results point out that mystery shoppers and electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) applied in e-commerce are more efficient than AR and VR technologies applied in services and industry, as reflected in the company’s performance. Furthermore, customer–employee interactions and communications with eWOM in e-commerce are more efficient than WOM used in services and industry. This paper contains both theoretical and practical contributions by offering a new, short-time innovative tool for the continuous improvement of the company with applications in different fields.

1. Introduction

In the technology century, competitive advantages reflect an organization’s ability to achieve high performance through proper, effective, and efficient management. These coordinates are fundamental in the current economic environment marked by increased technological and informational complexity and social changes with consequences on employees’ and consumers’ personalities []. Strategy can be customized, and each company utilizes the decisions considered most effective. Porter [] has become a classic for the three types of strategies that companies can adopt to face competition:

- Concentrated effort strategy;

- Differentiation strategy through products, services, outlets, and prices [];

- Strategy of global domination through costs.

The philosophy of any customer-centered company must be the customer before all. It must be based on the continuous improvement of both the products and services it provides regardless of the sector. From this philosophy, results the importance and necessity of customer satisfaction analysis. Recent research reflects the assessment of customer satisfaction from different perspectives, using quantitative, statistical, behavioral, qualitative, and intrinsic tools. Measuring customer satisfaction is one of the most important elements that has come to the attention of companies and organizations in all sectors []. Customer satisfaction must be expressed in measurable parameters as one of the key performance indicators (KPIs) of the companies. Customer satisfaction as a company performance indicator is difficult to achieve in terms of employee motivation and involves that all employees have direct contact with the customer, face-to-face or by electronic platforms (e-mail, chat, etc.). Customer satisfaction must motivate employees to achieve the highest standards and, in consequence, constantly increase labor productivity. In industrial sectors, the customer is not the direct consumer. Moreover, the purchasing process usually involves more people with different roles, each contributing to this final process.

Based on these considerations and using (as a starting point) the concepts of Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma, this paper contributes (both theoretically and practically) to the development of international scientific literature by introducing a new and innovative measurement tool together with the specific implementation methodology. Our research is a complex one by presenting, comparatively, the results of its implementation in three different sectors:

- Online commerce;

- Package delivery services;

- Automotive industry.

These research results were obtained during the doctoral research of the first author under the coordination of the second author. The authors applied the proposed indicator and methodology as pilot research in e-commerce, the results being published in []. During the doctoral research, the authors extended the implementation of the indicator by adapting the implementation methodology for the automotive industry and service sectors to compare their continuous improvement processes, customer-oriented strategies, and the cost reduction management of these companies. The main scope was to develop and adapt the new indicator and the implementation methodology according to each sector’s specificities. All the conditions and details about the implementation methodology are presented in the Material and Methods section.

The authors name the new indicator the Spc—The Assessment System of Employee Performance according to Customer Satisfaction []. The implementation method of the Spc indicator—is named ITA Methodology (Initiation—Testing—Application). They both directly contribute to sustainable company growth, as we further demonstrate through the performance indicators of the three companies from the research.

By conducting a literature review (detailed in the next section), we noticed the lack of a specific tool to quantify the tripartite relation customer satisfaction—employee performance—company performance; therefore, we consider our research results to be an important scientific contribution to the field, both theoretically (by introducing a new indicator Spc and a new implementation methodology, ITA) and practically (based on the results of their implementation in three different fields such as services, industry, and e-commerce). The proposed measurement tool, the Spc and its specific methodology (ITA methodology), fill a gap in the literature:

- They are the first measurement tools that simultaneously take into consideration: customer satisfaction, employee performance, and company performance.

- The implementation methodology used new electronics technologies and information systems, as follows: augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) Spectacles VR-BOX v2.0, electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM), VR glasses, chat, platform Warp Studio, OCS (Online Comments System) platform and Kahoot platform.

- There are well-known tools for measuring service/product quality, customer satisfaction (e.g., SERVQUAL), and continuous company improvement (e.g., Six Sigma, Lean Six Sigma, EFQM Excellence Model of European Foundation Quality Model). These tools work separately from only one direction and from the QMS (Quality Management System), not as an interface of customer satisfaction—employee performance—company performance as Spc and ITA methodology does.

- Our paper specifically corresponds to the new trends in the digital era and focuses on how information technologies, electronic multimedia, and computer science change business models and significantly affect companies’ performance. The rapid penetration of information technologies brings new opportunities for innovation, continuously improving and increasing efficiency and identifying key applications of information technology in practice. In this context, our research contributes to investigating the application of such technologies and information systems as those mentioned above in the business area.

The aim of the paper is to analyze the efficiency increase in employee performance assessment systems in relation to performance economic indicators (KPIs) starting from customer satisfaction assessment based on the results of a pilot study in the e-commerce sector made by the authors during their doctoral research [] by adapting them for package delivery services and the automotive industry by introducing ITA methodology and the Spc indicator.

As mentioned above, the Spc indicator and ITA methodology were developed and proposed by the authors and the information system and digital technologies were used for implementation: AR (augmented reality) and VR (virtual reality technologies) [].

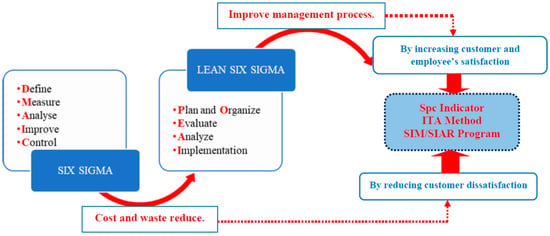

Our research is important from the perspective of the company’s economic performance, which is often determined in economic terms []. Regarding these aspects, in the present research, KPIs were considered (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework of the research.

- (1)

- Decreasing the number of NRR (Negative Response Rate) followed by decreasing the number of dissatisfied customers and the number of dissatisfied employees;

- (2)

- Total cost reduction;

- (3)

- Waste reduction through economic efficiency of the yield of production factors (Eeypf) and economic efficiency on the consumption of production factors (Eecpf);

- (4)

- Continuous improvement of the management process;

- (5)

- Economic performance measured by turnover and profit.

In our research, the element “key” from KPIs is considered the competitive advantage of the companies to have satisfied customers and implicitly satisfied employees. The “performance” element is given by all of the economic performance indicators mentioned above. The “indicator” is considered to be the moment before implementing ITA Methodology and Spc (considered M0) for each sector and the future corrections for more sectors. The conceptual framework is presented in Figure 1: the main concepts, Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma, used as the reference for developing the method, the indicator, and the implementation program proposed by the authors, while the conceptual and methodological aspects are detailed in the following sections.

Customer satisfaction is most important because, without satisfied customers, many companies could not survive. Achieving success in business depends on many factors, mainly on participants’ values []. Customer satisfaction is directly related to company performance. In modern marketing, customer satisfaction is considered a key element of business success []. Customer satisfaction also influences future purchasing decisions. Therefore, an important role is played by the quality of company products and services, their selling techniques, and employees’ attitude toward customers. Companies strive for sustainable sales and profit increases, strengthening the relationship with their customers by expanding their loyal customers []. The strategy of maximizing customer satisfaction is based on the exploitation of potential sales for existing customers, most often considering price reductions, various bonuses, loyalty points, etc. []. However, we cannot talk about customer satisfaction if there is a complaint. Therefore, this aspect is another important starting point in our research by taking into consideration the NRR (negative response rate) indicator used by an e-commerce company as the initial analysis moment (M0-before implementing Spc and ITA methodology) and further as the implementation through SIM (Spc Indicator, ITA Methodology, and the Mystery Shopper) and SIAR (Spc indicator, ITA Methodology, and AR technology for services, respectively, VR technology for automotive industry) programs. Our research also considers the significant transition from physical oral communication (WOM—word-of-mouth) to electronic oral communication (eWOM), even more obvious since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic []. In the customer–employee direct relations, there are numerous differences between the two communication forms [].

There are also situations when companies constantly increase customer satisfaction, but only a small fraction of the customers return. In our research, we take this aspect into consideration by measuring the rate of return (in percent) from each company because many companies lose customers continually, even if they have a high degree of customer satisfaction [].

2. Literature Review

Because the present paper introduces a new measurement tool and a new methodology for implementing it, we present in the following subsections a short literature review for each theoretical concept that formed the basis of the conception of the Spc indicator and ITA Methodology following the conceptual framework of the research from Figure 1.

2.1. Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma

Six Sigma is an applied methodology to improve business performance [], minimize errors and defects [,], and maximize value []—basically the most effective method used to improve organization performance []. Six Sigma aims to satisfy the customer and earn their loyalty, and, for the success of these steps, the active involvement of employees is necessary, as in problems identified by the DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) method [,]. Any business can be improved by Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma []. Six Sigma can facilitate the solving of company problems [], adapted to the dynamics of current management [] and on cost reduction [,].

Lean Six Sigma (LLS), introduced by George in 2002 [], unlike Six Sigma, is a concept about process change and process improvement, eliminating and reducing the process variation [] that directly involves employees in this process [] for jointly developing a gradual solving strategy []. LLS is segmented into four phases, creating value [] according to Figure 1, and has numerous benefits []: high quality and efficiency, increased employee motivation, improved customer relationships, improved response reaction, increased productivity and profit, etc. Although the pros regarding these methods’ effectiveness are numerous, there are also opinions stating that these methods ignore the human factor [].

Both methods help the company focus on issues that improve productivity, eliminating unnecessary processes and unusual activities that would be a barrier to increasing the company’s economic efficiency and performance. Six Sigma is based on profit maximization and customer satisfaction, as most customers, when dissatisfied, share this dissatisfaction with other customers, thus boycotting the company’s business []. Six Sigma tries to improve existing goods and services with better control over resources, optimizing costs, time, and product quality []. LSS is a technique that improves productivity and increases value, making improvements in terms of customer satisfaction, price level, quality, and other important aspects []. LSS starts with customers, with the main objective to eliminate any issues that would lead to customer dissatisfaction, offering an opportunity to develop the business, and creating a relationship between customer and company, by meeting its requirements today, not tomorrow []. Improving company procedures, LLS improves production, as reflected in the company revenues. LLS is more efficient by allowing an increase in production and customer satisfaction [].

2.2. Customer Satisfaction—Short Evolution of Measurement Methods and Concepts

In the scientific literature, customer satisfaction has many definitions, the terms “consumer satisfaction” and “customer satisfaction” being synonymous [], while important elements in defining customer satisfaction are []:

- Customer satisfaction is an affective or cognitive response that can vary in intensity;

- The response focuses on a specific element: product, expectations, services, etc.;

- The answer is specific only to a specific period: after the purchasing experience, after consumption, etc.

AT&T was the first company to introduce marketing research different from what had existed on the market in the 1970s, namely SAM—Satisfaction Attitude Measurement, carried out by mail [], followed by the Cardozo model based on understanding the impact of customer satisfaction on its future purchases []. Howard & Seth’s model is based on inputs that stimulate the purchasing process, perceptions, analysis, and outputs []. Day and Hunt’s research [], also in the 1970s, focused on the customer satisfaction—financial performance relation, while customer loyalty as company intangible assets was later developed and included []. However, customer satisfaction should not be used as a single indicator of loyalty [,] and must be analyzed in the customer–employee and customer–company relationships [].

Numerous studies have shown that the main determinant of trust is satisfaction accumulated over time because of transactions carried out on the market []. Regardless of the variables in the measurement model or method, the possibility of its adjustment and adaptation must exist [].

With the development of the digital economy, market and consumer trends have created a new approach regarding customer loyalty interpretation. The competitive dynamics of the competitive environment, the progressive saturation of many markets, and the structural changes in exchange processes induced by the emergence of the digital economy [] have supported the progressive importance of customer satisfaction, leading to an increased interest in the interconnections between supply and demand. However, in recent years, the study of consumer behavior has shown that expanding the research on the customer–product interaction can reveal more information about customer loyalty []. In the 1980s, a new concept was introduced in measuring customer satisfaction, i.e., trust, being considered a determining factor in the customer–producer relationship [].

The areas of research related to customer satisfaction are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Customer satisfaction research—comparative table.

2.3. Interface Quality—Employees—Customers—Company Performance

Technology has moved from the industrial to digital area, creating a deep impact on both producers’ and consumers’ behavior. The main aspects characterizing a business with quality products/services are high level of customer retention (loyalty), low costs, high profit rates, low staff fluctuation, staff motivation, etc., practically the Six Sigma concept.

A company’s performance depends on several efficiency indicators, such as cost, profit, and productivity. Six Sigma’s DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, and control) elements are very important in increasing a company’s economic efficiency [].

An effective method for improving the quality of direct contacts between customers and employees is the mystery shopper [], which, as well as Six Sigma, minimizes errors and maximizes value []. Some companies choose to become customer-centered companies, “earth’s most customer-centric company”.

The concepts of the Six Sigma method were applied to our pilot research in e-commerce. The information collected during mystery shopping is used to help a company better formulate its requirements for employees and improve the way customers are served []. The aim of a mystery shopper is not to penalize employees, but to identify certain problems and solve them to create an image of the customer’s experience.

Employees must be permanently educated to have a responsible attitude and meet customers’ demands [], while education can be formal, informal, or non-formal []. The way a customer is served can be decisive in competition between companies. Whether it is the speed of service or the complementary services, all can add something to the direct customer–employee interaction. In order to be able to talk about employee loyalty to the company, it is preferable that, first, the organization shows its attachment to employees []. Furthermore, a powerful product on the market will create a strong image for the company [].

The main company objective is to meet consumer needs. At some point, the company will have dissatisfied customers. Most of them, when expressing their discontent in the form of a complaint, have a state of disappointment and frustration [], which can be solved by following essential rules in the employee–customer communication [,,]. Today, customer satisfaction is no longer enough—it requires satisfying customers []. The company can create an advantage over the competition by identifying what is essential for customers, and one of the ways to obtain this information is directly from customers. Most of the time, this will not produce an immediate effect, but it is a gain, leading to results []. The continuous improvement of the employee–customer relationship can only bring benefits [].

The increase in cognitive power and affirmation of individual consumption patterns, correlated with a gradual increase in customer expectations compared to market supply, has emphasized a dynamic relation between the business system and the customer []. The atmosphere created by the company during the purchase will influence future customer purchases in that company. Kim’s conceptual model in 2006, developed by Chebat and Morrin in 2007 [], presents this connection between the store’s atmosphere and emotional status [].

Customers can purchase products both online and offline. Increased market volatility, uncertainty, and rapid changes characterizing economic and social environments and online environment development, different from traditional markets, have revealed some perspectives that are beneficial to classical markets in the acquisition process []. There may be several factors influencing this communication process between employee and customer (culture, employee/customer status, online/face-to-face dialogue environment, etc.). Adopting eWOM communication is a powerful mechanism for generating the response for a product []. The customer is stimulated through eWOM to express their opinions (positive or negative) so that the information can be processed []. This element is an important source of information for both the company and other customers []. Electronic WOM can increase a company’s long-term profitability by collecting information about customers and accessing the company’s platforms or other social media [].

The purchasing atmosphere influences information processing, facilitating the orientation to negative information or the orientation of filters toward the perception of positive product elements []. Competition brings to market the same product at the same price, but customer service can place the company in a positive light [] and can differentiate it from its competitors. Job satisfaction creates a positive atmosphere in any organization and leads directly to increasing individual attachment to an organization [] alongside the existence of an organized environment []. Consumer utilitarian behavior is a rational approach involving an efficient purchase []. In this context, consumers can assess the experience as an achievement of the pursued objective.

3. Materials and Methods

In actual digital economies, information technologies, computer-based science, and electronic tools are intensively used as competitive advantages for companies. Therefore:

- The based concept of Six Sigma used in this research is about process change and process improvement [], which directly involves the employee in this process [], for a joint gradual solving strategy [].

- The concept of Lean Six Sigma, referring to the main objective to reduce customer dissatisfaction [], creates the possibility of adjustments and adaptation that must exist in a company [].

- The necessity that employees must be permanently educated in order to have a responsible attitude and meet customers’ demands [] and the importance of the continuous improvement of the employee–customer relationship that could bring benefits to the company [].

These points represent the main theoretical foundations for the first research hypothesis:

H1.

A growth and development program requires continuous improvements related, adapted, and updated to the period of time in which it is applied.

For the second research hypothesis, the theoretical foundations are based on and starting from the fact that:

- Based on the Six Sigma principles, a company must adapt to the dynamic of current management [] for a joint gradual solving strategy [];

- Regarding the customer satisfaction measurement tool, a possibility of its adjustments and adaptations must exist in a competitive company [];

- By ensuring the important interface quality—employees—customers—company performance for a competitive company, the education of the employee can be formal, informal, or non-formal [].

Based on this theoretical framework, we formulated the second research hypothesis.

H2.

Performance evaluation systems require innovative adjustments by including elements from other sectors.

Due to the novelty of the new measurement indicator (Spc), its implementation (ITA methodology), the aim and objectives of our research (the validation or invalidation of these results in other economic sectors: services and industry), the lack of similar studies in the literature, the theoretical and practical concepts from the literature review in the previous section directly linked to our research, we used as research hypotheses the same ones as in the pilot research applied in e-commerce during the doctoral research of one of the authors, and already published by the authors [] as follows:

- H1: A growth and development program requires continuous improvements related, adapted, and updated to the period of time in which it is applied [,,,,,].

- H2: Performance evaluation systems require innovative adjustments by including elements from other sectors [,,,].

The research hypotheses were formulated in line with the references mentioned in the literature review section taking into consideration that the continuous improvement process plays a critical and strategic role for organizations with the final purpose of increasing company KPIs. Another scientific consideration for testing our research hypotheses is, according to the literature review, that the traditional methods for assessing company performance in the new digital economy era have deficiencies giving only a static and retrospective view. Therefore, in the digital economy and especially after the use of online communication in all domains after the COVID-19 pandemic, a modern and innovative measurement tool is necessary with the main scope to emphasize the need for both consumer and employee satisfaction.

Based on the conceptual framework described in Figure 1, data were collected between December 2018 and September 2020 in different time intervals depending on the sector. The research sample has a total of 121 subjects from the company’s employees who directly interact with customers:

- 32 employees from an e-commerce company;

- 67 employees from a services company (parcel delivery);

- 22 employees from an automotive industry company.

For the calculus of the Spc indicator for each of the three companies, the following formula was used:

where:

- Spc = the Spc indicator;

- WmL = average labor productivity;

- Maps = weighted arithmetic average of customer satisfaction;

- Cha = salary expenses per employee per hour (in Euro);

- t = average time to solve a specific task;

- Σc = total amount of contacts (employee effort).

The first element of the Spc indicator, WmL was collected differently according to the specific activity of the companies:

- For e-commerce, the WmL represents the average number of direct contacts resolved (customer—employee) per hour per employee by chat or/and phone;

- For parcel delivery services, the WmL represents the average number of packages delivered (voluminous or simple) per hour per employee;

- For the automotive industry, the WmL represents the average time to dismantle or deliver a part/piece.

For the Maps element, for all three companies, the same method was used to collect the information by an e-mail sent to all customers with a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire (1—totally disagree; …5—totally agree) immediately after the personal employee—customer contact to measure customer satisfaction. The questionnaire directly refers to order evaluation and contained four items regarding customer satisfaction: transport quality, communication quality with the company’s employees, promptness of the employee to serve the customer, and company prices.

The Cha element has the same significance for all three sectors: the expenses per hour, in Euro, per employee.

For interpretation of the Spc indicator values for all three companies, a legend was established empirically (Table 2):

Table 2.

Comparative table for describing Spc indicator variables and implementation methodology.

- For values 0.00–0.09, the Spc indicator shows poor employee efficiency;

- For values 0.10–0.19, it indicates a medium efficiency;

- For values 0.20–0.29, the Spc indicates a good efficiency of the employees;

- For values 0.30–0.39, the significance of the Spc is very good;

- Over or equal to 0.40, the Spc shows excellent employee efficiency.

In Table 2, methodological information is structured regarding the Spc formula indicator [], the elements, variables, implementation method and their description in the three sectors. In the column named E-commerce (pilot study) from Table 2, there are already published results [] from the pilot study during the period December 2018–March 2019 on 32 employees using the SIM program (Spc indicator, ITA Methodology, and Mystery Shopper). These results were considered the starting point for the implementation in the next companies and the base for adapting the SIM program and transforming it into the SIAR program (Spc indicator, ITA Methodology, AR technology for services, VR technology for automotive industry).

For the first step of the ITA method implementation on the employees from each company, the initiation, different strategies, and tools for the employees’ preparation were used according to the specific activities of the organizations from the study.

- For electronic commerce, the OCS (online comment system) platform of the company was used by the authors together with the company assistant;

- For the package delivery services, the authors used AR technology and VR Spectacles VR-BOX v 2.0 and VR glasses to optimize the storage and transport vehicle spaces;

- For the automotive industry, VR technology and Warp Studio Platform were used for initiating the employee.

For the second step of the ITA methodology, the Testing, also different strategies were used: the Mystery Shopper and the focus group for e-commerce, the Mystery Shopper and Kahoot platform for services and industry.

For the third step, to measure and assess the impact of the application of the Spc indicator and ITA methodology on the company’s KPIs, the following economic indicators were used: the turnover, profit, total costs (all in Euros), number of employees, Eeypf (economic efficiency of the yield of production factors (the value must be over 1 unit)), Eecpf (economic efficiency on the consumption of production factors (the value must be under 1 unit)), and the rate of return (in %).

The ITA methodology (Initiating—Testing—Application) of implementing the Spc indicator is based on management functions [], as the main objective of this method is economic development. The first component of the method aims to increase company performance [] and allows the employee to find solutions and make the change []. Employees operate in different environments; therefore, the training must be customized to the company specificities [], an aspect which was also respected in the current research, being adapted for each of the three sectors. To see the readiness of employees to solve a problem requires testing []. This involves employee evaluation, i.e., measurement and quantitative assessment of training effects [], and at the testing stage, it can be observed whether the employee is suitable for that position within the company [] based on feedback received [].

For calculus and graphical representation of data, Microsoft Excel was used.

4. Results

In this paragraph, we comparatively present the results from the three sectors: e-commerce published in the pilot research during the doctoral studies of one of the authors [], courier services, and the automotive industry. The purpose of this paper is to analyze: (1) for which of the three sectors the indicator recorded the best values of KPIs, (2) the period of time when improvements were observed, and (3) their evidence in the company’s performance. Thus, based on the information from Table 2, we present (Table 3) the average values for each moment (before and during the implementation of the ITA method and the Spc indicator), mentioning the interpretation of the Spc values.

Table 3.

Average values for the elements of the Spc indicator before and after implementation.

According to the results from Table 3, in the e-commerce sector, the Spc indicator recorded higher values since the first month of implementation (M1), with an improvement in values from medium to good in the last 2 months (M2 and M3). It follows the same upward trend as the values of the Maps element even if, in the last month, the average number of hours worked/month is the lowest, which practically proves the effectiveness of the tool and the ITA implementation method. The same upward trend was also recorded for the average labor productivity and the number of contacts/hour.

For the services sector, the implementation results are not so spectacular, but it is important to notice the increase in the total number of contacts, the average number of contacts/hour, and the average labor productivity. The average values of the Spc indicator maintain an average level from the initial moment M0 until the end of the implementation period. The service company was the company with the biggest number of employees in the total research.

For the automotive industry sector, the Spc indicator has evolved from weak to medium, with an upward trend for the Maps variables, the average labor productivity, and the total number of dismembered parts and a relatively constant value over all three months for the average number of dismembered parts per hour by an employee.

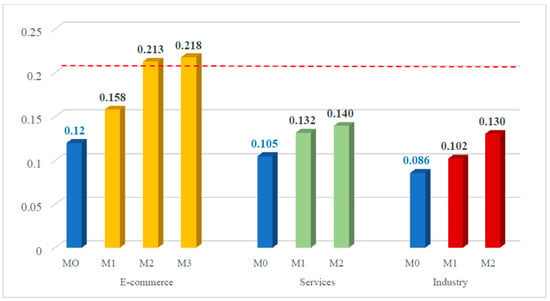

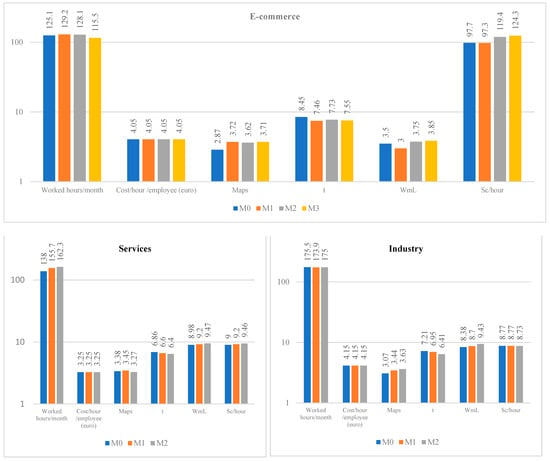

In Figure 2, the average values of the Spc indicator are presented for the entire research period, comparatively for all researched sectors. The superiority of the values for e-commerce can be observed.

Figure 2.

Average values of Spc indicator for each indicator before and after Spc implementation. (Note: M0 represents the moment before implementation (blue color) and from M1 to M2; M3 represents the moment after implementation: yellow for e-commerce, green for services and red for industry).

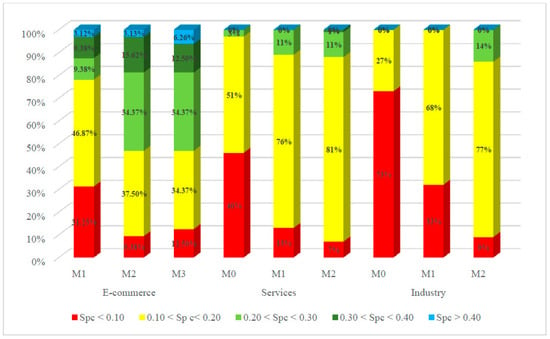

As major differences between employees in the same sector in terms of average labor productivity have been observed since the M0 moment of the research, in Figure 3, we represent the distribution and structure of the Spc indicator‘s ranges, highlighting the efficiency and performance of e-commerce, as the range of values is much more varied but also better positioned compared to the services and the industry sectors.

Figure 3.

Spc structure on the three sectors for each moment (before/after implementation). (Note: M0 represents the moment before implementation and from M1 to M2; M3 represents the moment after implementation).

The main practical purpose of the research was to highlight the potential of different types of employee training and their effect on the company KPIs mentioned in Table 4 (turnover, profit, total costs, number of employees, Eeypf (economic efficiency on the yield of production factors (with super unit values)), Eecpf (economic efficiency on the consumption of production factors (with subunit values)), rate of return).

Table 4.

The companies’ KPIs before and after Spc implementation.

The positive results from Table 4 prove the effectiveness of the Spc indicator through ITA methodology during the SIM and SIAR implementation programs. The results indicate much better, the results being highlighted in the e-commerce sector.

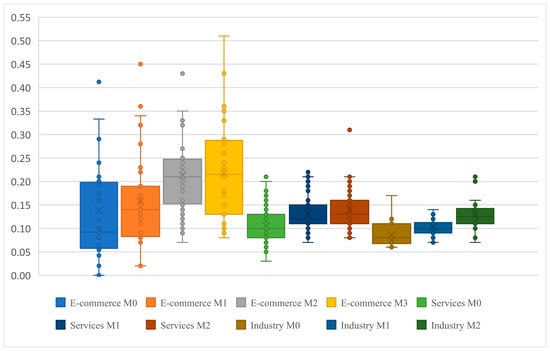

Since both the Spc indicator values and the KPIs indicators from e-commerce had better evolutions compared to services and industry, Figure 4 are presented the mean, median, range, using the box-plot graph, comparatively to a threshold of 0.2 (representing good values), above the average of the Spc indicator. For all three sectors, the ascending evolution of the average values is visible, as well as the variations around the average for each moment (before or after implementation).

Figure 4.

Box-plots for values of the Spc indicator for e-commerce, services, and industry.

Figure 5 shows the average values of each element of the Spc indicator formula by sector and by research moments (before and after implementation).

Figure 5.

Evolution of the Spc indicator elements/variables—average values/moment for each sector.

5. Discussion

Our research results emphasize that in communication by phone with customers, the employee’s tone is a decisive factor in solving their problems/complaints. Empathy can often make the difference between an amicable resolution of the case (considered a success when we have a satisfied customer) and failure (the loss of a customer) []. It depends on the company’s orientation on how to solve the complaint or the customer–employee communication problem; repercussions might appear in future interactions between them, which is a risk for the company. It is essential that the customer is satisfied by its experience with the company, but this might lead to the emergence of a phenomenon called customer moral hazard (CMH). A favorable solution to a problem/complaint might place the customer in a risky situation, knowing that he is protected against risk and the company in question bears the cost. Customer purchasing decisions may also be influenced by consumer-to-consumer communication (C2C) in eWOM []. To prevent these abusive behaviors of customers, it is necessary to continuously educate and train both employees and customers [].

Nowadays, information technologies and the electronic communication path with clients have taken over the daily system of each person, forming the basis of postmodern society []. There are several factors influencing the educational and learning environment within a company, such as organizational culture, technology, and economic aspects. Technology properly used and adapted to the needs of each sector could contribute to the development of the employer–employee–customer relationship and introduce new approaches in the process of employee improvement and cooperation between employees to provide access to diverse information. It is also used to adapt learning experiences with the stated purpose of satisfying requirements, real needs, and latent needs of customers [].

The Augmented Reality (AR)-based learning system is a method allowing users of computing technology and new digital tools to directly contribute to the efficiency of the employee performance improvement processes [,,] with direct effects on increasing customer satisfaction and company KPIs []. At the international level, several studies for and against the use of these innovative learning and evaluation methods of hard and soft skills have been carried out [], and any improvement (soft skills) is based on formal education. Starting from employee training in development, assembly, quality control, and maintenance [], all these company sectors benefit from AR implementation, primarily due to increased productivity and secondly due to reduced costs.

To be able to implement AR and VR technologies within an activity, a new attitude regarding the employee training process is necessary. For improved results, active training must first be developed. Active learning with AR and/or VR technologies can contribute to the continuous training of employees and the continuous improvement of the company.

Space, time, and contextualized understanding become part of a non-transferable learning experience. According to Gisbert, Esafe, and Camacho [], the benefits of using AR and 3D worlds as training tools are multiple, such as being autonomous learning processes [] and a useful tool in setting out prejudices and cultural barriers [], as follows:

- Provide a unique learning and knowledge exchange environment;

- Provide opportunities for group interactions engaged in learning;

- Improve communication skills (so that trainees can easily transfer course knowledge to real-life situations);

- Support creativity, exploration, and identity development.

The Spc indicator uses, in addition to the classic economic indicators (cost, productivity, profit, etc.), new customer service items (such as the NRR—measured within the e-commerce company). This is the customer service model used as the pilot research for the Spc indicator implementation and development for other sectors such as service and industry.

Customer satisfaction must come first and must be considered an element that all employees should focus on. Moreover, placing the customer at the center of the company is very important, but also other elements regarding employee activity (productivity, involved costs, and other important company indicators) must be considered.

The application of the ITA methodology starts by identifying the elements considered for implementation, i.e., staff training. At this stage, two learning aspects were pursued: (1) the processing one, which comprises processes developed in a learning segment; (2) the motivational one, which refers to employee involvement in the learning activity.

Competition characterizes the market economy, sets the market in action, and continues to push participants in economic life toward permanent development []. Regardless of the sector, the Spc indicator reflects the real economic situation of the company in relation to its customers, as long as it is properly applied. From the applied research within the three companies, specific aspects related to the Spc indicator’s implementation and adaptation in different companies from different sectors are highlighted.

The research results of the comparative analysis of the Spc indicator values and formula elements for e-commerce, services, and industry confirm the two holistic research hypotheses as follows:

- H1: A growth and development program requires continuous improvements related, adapted, and updated to the period of time in which it is applied;

- H2: Performance evaluation systems require innovative adjustments by including elements from other sectors.

The research hypotheses were formulated in line with the references mentioned in the literature review section and also considering that continuous improvement plays a critical and strategic role for the organizations, being known as an approach with the main purpose of enhancing organization performance [,]. Moreover, traditional methods and approaches to the evaluation of company performance are fundamental deficiencies in the fact that they provide only a retrospective view of the company’s competitive position that existed at some point in the past []. Thus, in the process of a company’s performance evaluation, modern and innovative performance evaluation methods (such as Spc and ITA methodology), combining financial and non-financial performance indicators and allowing the performance to be evaluated both quantitatively and qualitatively, should be used [].

Finding new ways to train employees is more difficult than ever, especially when information technology, digital economy, and computer science have gained such momentum. AR and VR technologies are highly effective tools that can be applied in any sector. Skills developed using AR technology are essential, and they are designed to address the intense challenges of knowledge and digitalization society, which has emphasized the usefulness of both AR/VR technologies and the internet of things (IoT) concept. The main criteria for the evaluation of such technologies must be effectiveness and functionality. Managers often focus mainly on efficiency instead of customer satisfaction []. The application of information technologies should not only be on the mental level, but also on the physical level. These information technologies can be effectively used, especially for group learning [].

These efforts have resulted in a key economic indicator, the profit, which is essential for any company in the market economy. Considering the customer at the heart of any successful economic activity, this research focus has been on its satisfaction and on how to increase it. Any company has both strengths and weaknesses, but it is essential that participants in the economic activity find competitive advantages over market competitors, identify new elements making the economic activity more efficient. Each of the three case studies reveals specific situations using the same application principles. To be fully efficient, the application of the SIAR program must be carried out from the employees’ own initiative, without constraints, and they must be aware of their role in the company’s growth.

The research subject refers to the issues of customer dissatisfaction increase following the interactions with company representatives, with direct consequences in decreasing the number of customers and implicitly reducing company performance. The causes of these situations lie in the absence of continuous employee training, stagnation of the training process, and thus limitation to routine work. Generally, these aspects of direct (by any means) employee–customer interactions are reflected in customer feedback, negatively affecting the company’s market image. In this research, we used as a starting point the analysis of causes for employee–customer tensions, and we found out that many of these problems really start from the employee.

The research was carried out in three sectors, with a different number of employees, based on pilot research in e-commerce/by testing and subsequently adapted the methodology for services and industry. The employee—customer interaction in e-commerce is made by chat, phone, and e-mail. For services (courier company), the interaction is direct and face-to-face, while for industry (automotive company), it is both face-to-face and electronic channels.

The research subject is of high interest currently as companies are constantly looking to identify new ways for sustainable growth, both nationally and internationally. In the 21st century, the aim of a company is not only to obtain profit by any means, but also to build a lasting relationship with customers that needs to be continuously improved and strengthened so that the customer is aware of their role in company growth.

To highlight these, another author’s contribution is identifying the need for a new measurement tool to establish and measure the tripartite relation: customer satisfaction—employee performance—company performance.

To achieve the research aim and objectives, both classical and innovative concepts were used: we have developed, tested, and proposed the introduction of an innovative tool for measuring employee efficiency determined by both employee activity and customer satisfaction regarding the purchased product or service.

The research results highlight the way in which information technology, electronic communication channels, and company KPIs can lead to positive and effective results within a company, regardless of its sector. The idea of developing this indicator is based on the concepts and objectives of the Six Sigma method in services, mainly to understand how certain errors occur in customer relations, specifically to identify customer dissatisfaction causes.

6. Conclusions

From the results presented above, we can conclude that the testing method using the Mystery Shopper of the ITA methodology applied in e-commerce is more efficient than AR and VR technologies applied in services and industry. Thus, efficiency is reflected in the Spc indicator evolution and, most importantly, in the evolution of the company performance indicators (KPIs).

We can also conclude that, given that the types of customer–employee interactions were different (eWOM in e-commerce and WOM in services and industry), in services and industry, customer feedback being perceived directly by the employee, eWOM communication is more efficient than WOM. The pilot research results in e-commerce highlighted employee aversion to risk. With this company’s attitude toward employees, instead of the problems being solved, we concluded—with the help of the focus group—that the organizational structure actually made things worse and that taking risks was not rewarded by the company. Therefore, some strictness in setting certain objectives would prevent managers from achieving maximum efficiency as employees do not take risks []. A solution to this problem can be the formation of eight employee groups, in which the Spc indicator is taken as an average of the eight employees (i.e., a group evaluation, not an individual one).

Improving company performance is the main goal, but the context and method of action are much more complex. To achieve this goal, it is necessary to improve several economic indicators and continuously improve by re-educating/training employees in terms of attitude towards customers. This aspect is more important now, when loyalty and attraction of new customers are essential for business sustainability regardless of the sector.

A fundamental company policy is that customer satisfaction is the most effective indicator, but that it is not always enough. The idea of employees depending solely on customer satisfaction is a rather delicate one, as many of them felt discouraged. We consider that, besides this, the employee productivity indicators, hourly cost per employee, and duration of the solution (i.e., all elements underlying the Spc indicator design) are also important. The Spc indicator creates a real picture regarding customer satisfaction—employee performance relationship—as an important element in increasing company efficiency and performance.

Therefore, we consider this paper to contain important scientific contributions both theoretically and practically, as the application of the Spc indicator and the ITA methodology have led to evidence of the following real advantages for companies not only from e-commerce, service, and industry sectors but also from other fields. Our main theoretical contribution is linked to:

- Increasing labor productivity, followed by an increase in the number of contacts for an employee.

- Improving the cognitive process of employees within the company, which was directly reflected in the improvement of the company’s economic and financial indicators.

- Improving the relationship between employees and customers, leading to increased satisfaction.

- Reorganization of the employee program resulting in increased staff efficiency.

- Better control over the operating parameters of each employee and the entire sector by introducing an SIM and SIAR program.

The paper presents important practical contributions for the stakeholders:

- The applied research presented in this paper reveals real situations at a national level in two sectors, one secondary and one tertiary; the latter being the most developed, not only at a national but also at a global level.

- The Spc indicator and ITA methodology introduced and implemented by the authors do not intend to eliminate the methods already used at the company level.

- The Spc indicator and ITA methodology introduced and implemented by the authors show that some aspects need to be continuously improved to increase the company’s economic performance, which is often determined in economic terms [].

Our results emphasize that electronic tools and digital technologies for communications, such as eWOM, chat, OCS platform, and e-mail, together with AR and VR technologies, improve customer—employee—company communication with the main impact on company KPIs.

The present research has limits linked to the relatively small number of subjects participating in the research due to the targeted SMEs from three different fields for implementations of the Spc and ITA methodology. This option was taken into consideration due to our presumed reluctance of the companies to participate in the research. Therefore, for future research, we intend to extrapolate the investigation to include medium-sized companies, both national and international.

The research subject is of high interest currently in the research field of customer satisfaction assessment as companies are constantly looking for new solutions to increase customer satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.-D.L. and M.R.G.; methodology, I.-D.L. and M.R.G.; validation, I.-D.L., M.R.G. and M.K.; formal analysis, I.-D.L. and M.R.G.; investigation, I.-D.L.; data curation, I.-D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, I.-D.L., M.R.G. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.R.G. and M.K.; visualization, I.-D.L., M.R.G. and M.K.; supervision, M.R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alecu, C.; Gherasim, O. Metode şi Tehnici Utilizate în Managementul Organizaţiei; Pro Universitaria: Bucuresti, Romania, 2015; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. Despre Concurenţă; Meteor Press: Bucuresti, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, N. Customer Satisfaction; Cogent: London, UK, 2007; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Legman, D.I.; Gabor, M.R. New Optimization Technique for Sustainable Manufacturing: The Implementation of the Spc Indicator (System of Evaluating Employee Performance Depending on Customer Satisfaction) as an Important Element of Satisfaction Measurement. Proc. MDPI 2020, 63, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Legman, D.I.; Gabor, M.R. Augmented Reality technology—A sustainable element for Industry 4.0. Acta Marisiensis Oecon. 2020, 14, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P.F. Managementul Strategic; Teora: Bucureşti, Romania, 2001; p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, S. Sustainable Event Management; Tirol: Kufstein, Austria, 2010; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Morgeson, V.F.; Mithas, S.; Keiningham, L.T.; Aksoy, L. An Investigation of the Cross-National Determinants of Customer Satisfaction. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauss, B. Effective Complaint Management, The Business Case for Customer Satisfaction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Butscher, S.A. Customer Loyalty Programmes and Clubs, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Ding, F.; Xu, M.; Mo, Z.; Jin, A. Investigating the Determinants of Decision-Making on Adoption of Public Cloud Computing in E-government. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2016, 24, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N. Managing Diversity, Innovation, and Infrastructure in Digital Business; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.; DeCarlo, N. Six Sigma for Dummies; Wiley Publishing Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Keki, B. Ultimate Six Sigma: Beyond Quality Experience; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Pai Bhale, N.G. Six Sigma in Service: Insights from Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Eng. 2017, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Robinson, P. Operations Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, A. Demystifying Six Sigma; American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, B.; Sproull, B. The Critical Methodology for Theory of Constraints, Lean, and Six Sigma; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Tetteh, E.G. Lean Six Sigma Approaches in Manufacturing, Services and Production; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Mockler, R. Management Strategic Multinational; Editura Economică: Bucureşti, Romania, 2001; p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- Prahoveanu, E. Economie politică—Fundamente de teorie economică; Editura Eficient: Bucureşti, Romania, 1997; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Legman, I.D.; Blaga, P. Six Sigma Method Important Element of Sustainability. Acta Marisiensis Oecon. 2019, 13, 37–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.L. Lean Six Sigma: Combining Six Sigma Quality with Lean Production Speed; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kesterson, R.K. The Intersection of Change Management and Lean Six Sigma; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D. The Field Guide to Achieving HR Excellence through Six Sigma; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Mihuţ, I. Euromanagement; Editura Economică: Bucureşti, Romania, 2002; p. 279. [Google Scholar]

- Plenert, G.; Plenert, J. Strategic Excellence in the Arhitecture, Engineering and Construction Industries; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Caroll, C.T. Six Sigma for Powerful Improvement; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.K.; Yen, C.T.; Chu, T.P. Using the design for Six Sigma approach with TRIZ for new product development. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 98, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikumapayi, O.M.; Akinlabi, E. Six Sigma versus lean manufacturing? An overview. Mater. Today-Proc. 2020, 26, 3275–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, M.S.; Rathi, R. Analysis and modeling the enablers of Green Lean Six Sigma implementation using Interpretive Structural Modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; He, Z.; Ahmad, N. Green, lean, Six Sigma barriers at a glance: A case from the construction sector of Pakistan. Build. Environ. 2019, 161, 106225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.J. Implementing Lean Six Sigma to overcome the production challenges in an aerospace company. Prod. Plan. Control 2016, 27, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, F. The Influence of Culture and Personality on Customer Satisfaction; Springer Gabler: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Giese, J.L.; Cote, J.A. Defining Customer Satisfaction. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2000, 1, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Siskos, Y. Customer Satisfaction Evaluation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Motivating Sustainable Consumption: A Review of Evidence on Consumer Behaviour and Behavioural Change. In Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity, the Social Psychology of Sustainable Consumption; 2005; Available online: https://timjackson.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Jackson.-2005.-Motivating-Sustainable-Consumption.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Burgess, P. Integrating the Packaging and Product Experience in Food and Beverages; Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2016; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Darroch, J. Knowledge management, innovation and firm performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2005, 9, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.O.; Sasser, E.W., Jr. Why Satisfied Customers Defect. 1995. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/1995/11/why-satisfied-customers-defect (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Chandrashekaran, M.; Rotte, K.N.; Tax, S.S.; Grewal, R. Satisfaction strength and customer loyalty. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 44, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.K.; Tse, D.K.; Chan, K.W. Strengthening customer loyalty through intimacy and passion: Roles of customer–firm affection and customer–staff relationships in services. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1989, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Fan, W.; Penner, J. Competitive actions and dynamics in the digital age: An empirical investigation of social networking firms. Inform. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 594–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsbrechts, E.; van Heerde, H.J.; Pauwels, K. Winners and losers in a major price war. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 499–518. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, P.H.; Kumar, R. Emotions, trust and relationship development in business relationships: A conceptual model for buyer-seller dyads. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 35, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaleeb, S.S. The trust concept: Research issues for channel distribution. Res. Mark. 1992, 11, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Narus, C.J.A. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnership. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Weitz, B. Determinants of continuity in conventional industrial channel dyads. Mark. Sci. 1989, 8, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurr, P.H.; Ozanne, J.L. Influence on exchange processes: Buyer’s preconceptions of a seller’s trustworthiness and bargaining toughness. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 11, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K.P.; Peters, L.D. Trust and direct marketing environments: A consumer perspective. J. Mark. Manag. 1997, 13, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurviez, P. The trust concept in the brand-consumer relationship. In Proceedings of the 25th EMAC Conference European Marketing Academy, Budapest, Hungary, 14–17 May 1996; Beràcs, J., Bauer, A., Simon, J., Eds.; Volume I, pp. 559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, L.A.; Evans, K.R.; Cowles, D. Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, K.; Ambler, T. The dark side of long-term relationships in marketing services. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Zaltman, G.; Deshpandè, R. Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Deshpandè, R.; Zaltman, G. Factors affecting trust in market research relationship. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, N. Cercetările de tip “clientul misterios”—Repere ale evolutiei marketingului modern/”Mystery Shoopper” Research—A Landmark of Modern Marketing. Rev. Mark. Online (RMkO) 2017, 2, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- PamInCa. The Essential Guide to Mystery Shopping; Happy About: Cupertino, CA, USA, 2009; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Potolea, D. Pregătire Psihopedagogică; Polirom: Bucureşti, Romania, 2008; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, C.D.; Schoenfeldt, L.F.; Shaw, J.B. An Introduction to Human Resource Management; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, J.N. The New Strategic Brand Management; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2008; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- Cava, R. Comunicarea cu Oamenii Dificili; Curtea Veche Publishing: Bucureşti, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, H.A.; Hildebrandt, H.W. Effective Business Communications; McGraw-HILL: Singapore, 1991; p. 611. [Google Scholar]

- Chiru, I. Comunicarea interpersonală; Tritonic: Bucureşti, Romania, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chris, D. Client o dată, client mereu: Cum să oferi servicii care iţi fidelizează clienţii; Editura Publică: Bucureşti, Romania, 2008; p. 298. [Google Scholar]

- von Weizsacker, E. Factor Four, Doubling Wealth-Halving Resource Use; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Lunt, P.K.; Livingstone, S. Mass Consumption and Personal Identity: Everyday Economic Experience; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S.; Hanssens, D.M. Marketing and firm value: Metrics, methods, findings, and future directions. J. Mark. Res. 2009, 46, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebat, J.C.; Morrin, M. Colors and cultures exploring the effects of mall décor on consumer perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A. A new conceptual framework for business consumer relationships. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2007, 25, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismgilova, E.; Slade, E.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth Communication on Intention to Buy: A Meta-Analysis. Inform. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 1203–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegele, M. Example, please! Comparing the effects of single customer reviews and aggregate review scores on online shoppers’ product evaluations. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, N.T.A.; Harun, A. Examining mediating effect of attitude towards electronic words-of mouth (eWOM) on the relation between the trust in eWOM source and intention to follow eWOM among Malaysian travelers. Asia Pacif. Manag. Rev. 2017, 22, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.L.; Tang, C.H. Hotel attribute performance, eWOM motivations and media choice. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- PMP. Market Experts. Competition Analysis: Definition, Objective, Scope and the Most Common Mistakes. Available online: https://www.pmrmarketexperts.com/en/competition-analysis-definition-scope/ (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Backstrom, K. Understanding Recreational Shopping: A new approach. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2006, 16, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, S.; Ringlstetter, M.J. Strategic Management of Professional Service Firms. Theory and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2011; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.M. General and Industrial Management by Henri Fayol. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livy, B. Corporate Personnel Management; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1988; p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, D. Les Resources Humaines; Editions d’Organisation: Paris, France, 1999; p. 442. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdin, J.L.; Peretti, J.M. The Success of Apprenticeships: Views of Stakeholders on Training and Learning; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Gabor, M.R.; Blaga, P.; Matiș, C. Supporting Employability by a Skills Assessment Innovative Tool—Sustainable Transnational Insights from Employers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, V. Theorie und Erfahrung in der psychologischen Forschung; LIT Verlag: Münster, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Armin, T. Human Resources Strategies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Goffee, R.; Jones, G. Why Should Anyone Be Led by You? What Takes to Be an Authentic Leader; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fader, P.S. Customer Centricity: Focus on the Right Customers for Strategic Advantage; Wharton Digital Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Morgan, S.; Wang, Y. The Strategies of China’s Firms: Resolving Dilemmas; Elsevier–Chandos Publishing: Waltham, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefănescu, F. Dezvoltare Durabilă şi Calitatea Vieţii; Editura Universităţii din Oradea: Oradea, Romania, 2007; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Bîrsan, J.; Moldoveanu, F.; Moldoveanu, A.; Morar, A.; Butean, A. Immersive education in smart educational buildings. eLearning Softw. Educ. 2020, 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S.; Kwon, S.; Moon, D.; Ko, T. Smart Facility Management Systems Utilizing Open BIM and Augmented/Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 35th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (ISARC2018), Berlin, Germany, 22–25 July 2018; pp. 846–853. [Google Scholar]

- Benko, H.; Jota, R.; Wilson, A. Mirage Table: Freehand interaction on a projected augmented reality tabletop. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 12), Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia, D.; Mendoza, M.; Gonzalez, E. Augmented Reality as a Tool for Production and Quality Monitoring. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 75, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, M.; Esteve, V.; Camacho, M. Delve into the deep: Learning potential in Metaverses and 3D worlds. eLearning Pap. 2011, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, H.; Joung, S. Self-regulation strategies and technologies for adaptive learning management systems for web-based instruction. In Proceedings of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, Chicago, IL, USA, 19–23 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zeki, S.; Bartels, A. The temporal order of binding visual attributes. Vis. Res. 2006, 46, 2280–2286. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, G. Comportament Organizational (Organizational Behaviour); Editura Economică: Bucureşti, Romania, 1998; p. 479. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, T. The role of performance measurement in continuous improvement. Int. J. Oper. Prod. 1999, 19, 1318–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Aleu, F.; Van Aken, E.M. Systematic literature review of critical success factors for continuous improvement projects. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2016, 7, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosova, A. Methods and approaches to the evaluation of company performance. Poprad Econ. Manag. Forum 2017, 31–36. Available online: https://www.pemf-conference.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Proceedings_PEMF_2017.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Narkuniene, J.; Ulbinaite, A. Comparative analysis of company performance evaluation methods. Entrep. Sustain. 2018, 6, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jivan, A. Managementul Serviciilor; Editura de Vest: Timişoara, Romania, 1998; p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Azawi, R.; Albadi, A.; Moghaddas, R.; Westlake, J. Exploring the Potential of Using Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality for Stem Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, J. Ce fac liderii cu adevărat (What Leaders Really Do?); Meteor Press: Bucureşti, Romania, 2008; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).