Abstract

Recent advancements in intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) driven by artificial intelligence (AI) have attracted substantial research interest, particularly in the domain of computer programming education. Given the diversity in learners’ backgrounds, cognitive abilities, and learning paces, the development of personalized tutoring strategies to support the effective attainment of learning objectives has become a critical challenge. This paper introduces personalized fuzzy logic strategies for intelligent programming tutoring (PerFuSIT), an innovative fuzzy logic-based module designed to select the most appropriate tutoring strategy from five available options, based on individual learner characteristics. The available strategies include revisiting previous content, progressing to the next topic, providing supplementary materials, assigning additional exercises, or advising the learner to take a break. PerFuSIT’s decision-making process incorporates a range of learner-specific parameters, such as performance metrics, error types, indicators of carelessness, frequency of help requests, and the time required to complete tasks. Embedded within the traditional ITS framework, PerFuSIT introduces a sophisticated reasoning mechanism for dynamically determining the optimal instructional approach. Experimental evaluations demonstrate that PerFuSIT significantly enhances learner performance and improves the overall efficacy of interactions with the ITS. The findings highlight the potential of fuzzy logic to optimize adaptive tutoring strategies by customizing instruction to individual learners’ strengths and weaknesses, thereby providing more effective and personalized educational support in programming instruction.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the fields of digital learning and educational technology have experienced significant advancements. Intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs) and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) have made an important contribution to these advancements. ITSs offer adaptive and personalized learning experiences that address the unique educational needs and preferences of individual learners [1,2,3,4,5]. They incorporate AI techniques that effectively model the learner’s characteristics and needs and make the system able to respond to them, emulating the way of thinking and the reactions of a human tutor [6,7,8,9,10,11]. As a result, the learner’s performance, engagement, and overall educational outcomes improve.

One domain that has particularly benefited from these advancements is computer programming education, a field in which skills are increasingly essential across various disciplines. Tutoring computer programming is confronted with challenges due to the diverse backgrounds, characteristics, needs, and learning pace of students [12,13]. Additionally, the rapidly evolving nature of programming necessitates frequent updates to instructional content and personalized approaches to teaching. Recognizing these challenges, substantial research has been conducted on advanced tutoring systems for teaching these skills [14,15,16]. Numerous researchers have developed ITSs for computer programming education [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Despite these efforts, educational outcomes in programming courses need further enhancement [25,26,27,28,29].

There are various challenges involved in ITSs for computer programming education. Particularly, they include modeling complex and vague data, like students’ knowledge and skill levels [30,31,32], a flexible error diagnosis mechanism that can identify a variety of error types (i.e., syntax errors, logic errors) [33,34], sophisticated decision-making processes and real-time data processing that allow for the provision of targeted personalized feedback [35,36], and dynamic adjustments of the tutoring strategies and processes. An AI technique that is able to address these challenges is fuzzy logic, a reasoning approach that effectively manages uncertainty by calculating with words and imitating the human way of thinking [37,38]. More specifically, fuzzy logic enables a more effective representation of students’ knowledge levels using linguistic terms [39,40,41], can detect and interpret errors in a more flexible way [42,43], and can emulate a human tutor’s cognitive processes and reactions through fuzzy rules, providing nuanced feedback [44,45]. Therefore, the strengths of fuzzy logic in relation to other AI methods that constitute it an effective approach to address the challenges of an ITS for computer programming are its ability to handle uncertainty, explainability, interpretability, and transparency in reasoning and its ability to combine multiple and overlapping criteria.

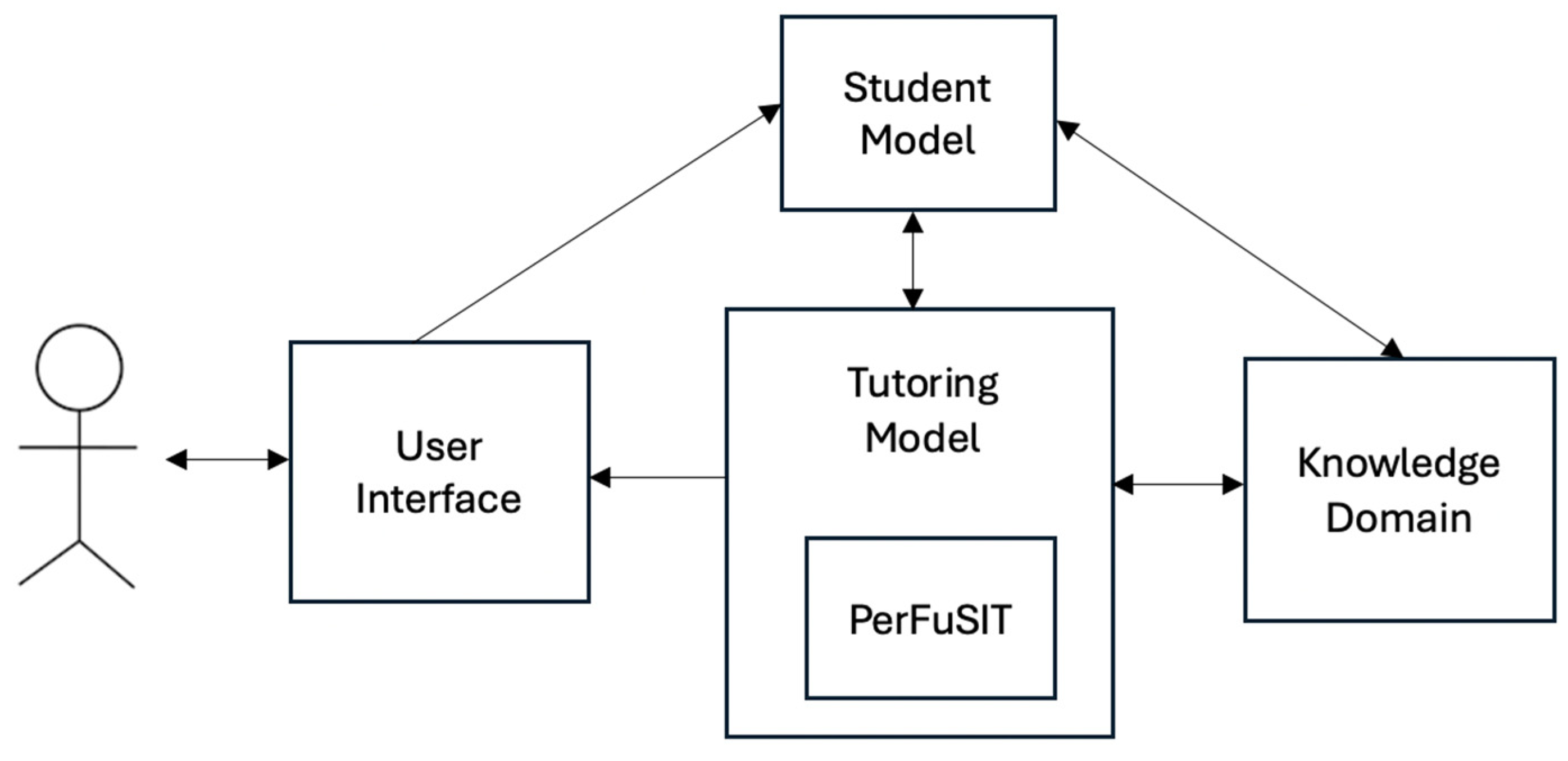

Therefore, this paper introduces personalized fuzzy logic strategies for intelligent programming tutoring (perFuSIT), an innovative fuzzy logic-based module that is responsible for selecting the most appropriate tutoring strategy based on the characteristics of learners within an intelligent system for teaching computer programming. PerFuSIT leverages fuzzy logic to model the inherent uncertainty and variability in learner performance and educational needs and dynamically adapts tutoring strategies. More specifically, PerFuSIT is a fuzzy inference system that takes into account the performance, types of errors, indicators of carelessness, frequency of help requests, and required time to solve exercises for each learner and selects the most optimal tutoring strategy for her/him, consulting the tutoring model and applying a set of fuzzy rules. PerFuSIT is a module of a comprehensive web-based ITS that teaches computer programming (Figure 1). The presented system has been used by undergraduate students of the department of Informatics of the University of Piraeus in Greece. The evaluation results show that PerFuSIT enhances learners’ performance and the efficacy of their interactions with the system. The findings indicate that PerFuSIT is a significant advancement in the development of intelligent tutoring systems for computer programming, with the potential to impact the broader landscape of personalized education. It showcases how fuzzy logic can be leveraged to develop more intelligent, adaptive, and effective learning systems.

Figure 1.

ITS that incorporates PerFuSIT.

2. Literature Review

ITSs include advanced educational technologies that allow them to dynamically adjust the educational content, feedback, and instructional methods to meet the unique learning needs and progress of individual learners. However, implementing adaptation in an ITS is a complex process that deals with a variety of challenges. To build systems that provide effective adaptation requires sophisticated algorithms and techniques [46,47]. Such a challenge is the uncertainty that characterizes the adaptive systems [48]. Fuzzy logic is an ideal method to deal with uncertainty, especially in cases in which it occurs, mainly due to imprecise, subjective, or ambiguous data, as is usually the case in ITSs [49].

In this literature review, there are works that concern the development of ITS for computer programming, which leverage fuzzy logic to provide personalized and adaptive learning experiences, but they are limited. Particularly, in [50], the authors used a fuzzy logic-based mechanism to determine students’ skill levels in a tutoring system for the programming language C. However, no diagnosis of error types nor personalized feedback is provided. Furthermore, no adaptive tutoring strategies are suggested according to the level of programming knowledge and progress of each individual student. Also, Photoboard [51] is another ITS that uses fuzzy logic to identify the knowledge level of novice learners in computer programming. Photoboard, in contrast to [50], identifies syntax errors and sends corresponding feedback to students. However, neither does this provide instructional solutions and adaptive tutoring strategies. Furthermore, in [52], the authors developed the COALA system, which uses fuzzy logic to assess the program (code) that a student writes in a tutoring system for computer programming. COALA uses fuzzy logic to represent a variety of parameters concerning the student program, like lines of code and complexity, and through fuzzy rules, generates feedback, including ways of correcting and improving the program quality. Similarly to the aforementioned works, COALA does not provide a comprehensive adaptive instructional strategy. In addition, in [53], the authors present FuzKSD, which is a fuzzy logic-based mechanism that is incorporated in a web-based ITS that teaches the programming language C. The operation of FuzKSD is based on fuzzy sets and fuzzy rules. Its aim is to dynamically identify the student’s knowledge level and its changes and model the learning or forgetting process. In this way, the system decides if each learner needs to repeat the current domain chapter, has to be transited to the next one, or has to return to a previous one to revise it. The presented system provides adaptive instruction; however, it is restricted to which chapter of the learning material each individual student has to read.

In addition, there are adaptive serious games for teaching computer programming, which incorporate fuzzy logic. In [54], the authors developed NanoDoc, an adaptive serious game for teaching the programming concepts of sequence and iteration to elementary school students. NanoDoc incorporates fuzzy logic to describe student knowledge levels and provides the appropriate working examples until the student obtains the required knowledge level. Therefore, it supports students in acquiring the desired knowledge in computer programming by providing targeted working examples, but it does not adapt the tutoring strategy to the learning needs of each individual student. Another serious game that incorporates fuzzy logic to offer adaptivity is FuzzEG [55]. FuzzEG describes the learner’s knowledge level through fuzzy sets and determines the level of difficulty of the quizzes and the extension of the game scenario so that the learner can interact with more educational content using a set of fuzzy rules. The fuzzy logic-based adaptation of FuzzEG aims to model the students’ knowledge level and determine the difficulty of exercises, but not to provide personalized tutoring strategies. Also, in [56], the authors present a computer programming serious game that uses a fuzzy logic-based mechanism that models the student’s skills and determines the difficulty of the game’s mission. Thus, the game adapts its challenges to each individual learner’s skills to support her/him in learning computer programming, but it does not provide any other instructional adjustment.

Regarding the abovementioned previous studies, we conclude that although fuzzy logic has been used for providing adaptive learning features in tutoring systems for computer programming, its use is limited. More specifically, fuzzy logic is usually used for modeling students’ knowledge or skill levels and determining the difficulty of the provided educational content and whether he/she should transition to the next chapter of the knowledge domain. Despite these advancements, the application of fuzzy logic for providing more nuanced adaptive instructional actions, like giving access to supplemental educational material, asking the student to solve more exercises, or advising the student to have a rest, to each individual learner needs further investigation. The presented mechanism aims to dynamically adapt instructional strategies based on the continuous assessment of learner performance and learning profile leveraging through a fuzzy logic-based mechanism. Particularly, PerFuSIT’s use of fuzzy logic goes beyond simple transitions between chapters or difficulty levels by adjusting various instructional strategies. It includes an advanced reasoning mechanism to select the optimal tutoring strategy from five available options, including revisiting previous content, progressing to the next topic, providing supplementary materials, assigning additional exercises, or advising the learner to take a break, in real time. The selection is based on various learner-specific parameters, which not only include the knowledge level but also the types of errors, signs of carelessness, frequency of help requests, and time spent on tasks. Therefore, PerFuSIT provides a more sophisticated reasoning mechanism that imitates a teacher’s way of thinking and behavior.

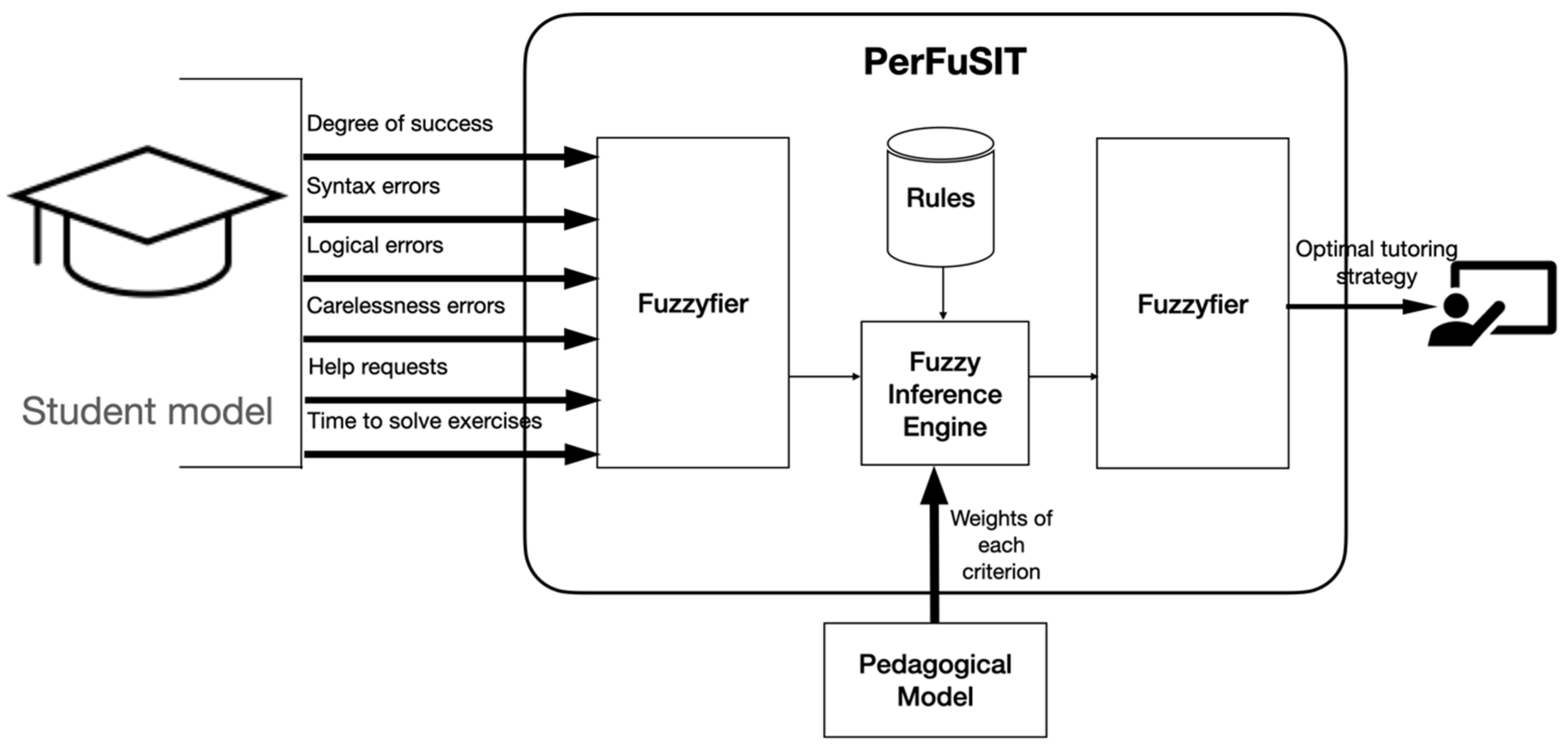

3. PerFuSIT

PerFuSIT is an innovative fuzzy-based mechanism for providing personalized tutoring strategies in an intelligent tutoring system that teaches computer programming (Figure 2). In more detail, PerFuSIT takes as inputs the student’s degree of success in the knowledge domain, the percentage of syntax and logical errors s/he makes, the frequency of mistakes that happen due to carelessness, the frequency of help requests, and the time s/he needs to solve exercises. These data are provided by the student model. Also, PerFuSIT takes as inputs the weights of each criterion. The weights are stored in the pedagogical model and are defined by tutors and experts in computer programming. The input data are fuzzified, and PerFuSIT applies weights and a set of fuzzy rules over them to recommend the most appropriate tutoring strategy among the five available, ranging from reviewing a chapter or moving on to the next one to providing supplemental content and additional exercises or rest.

Figure 2.

Architecture of PerFuSIT.

3.1. Available Tutoring Strategies

The available tutoring strategies from which PerFuSIT has to select the most appropriate for each individual learner are as follows:

- A1: Review the chapter;

- A2: Move to the next chapter;

- A3: Access supplemental resources;

- A4: Practice additional exercises;

- A5: Take a break.

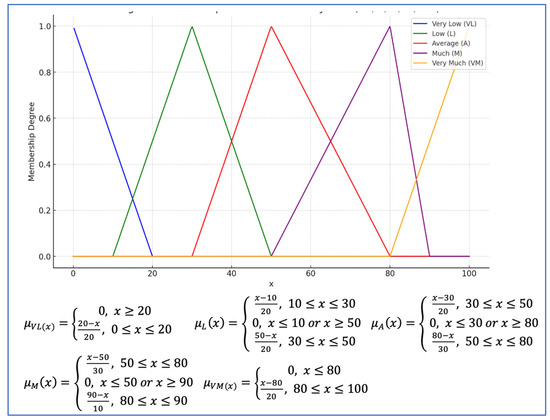

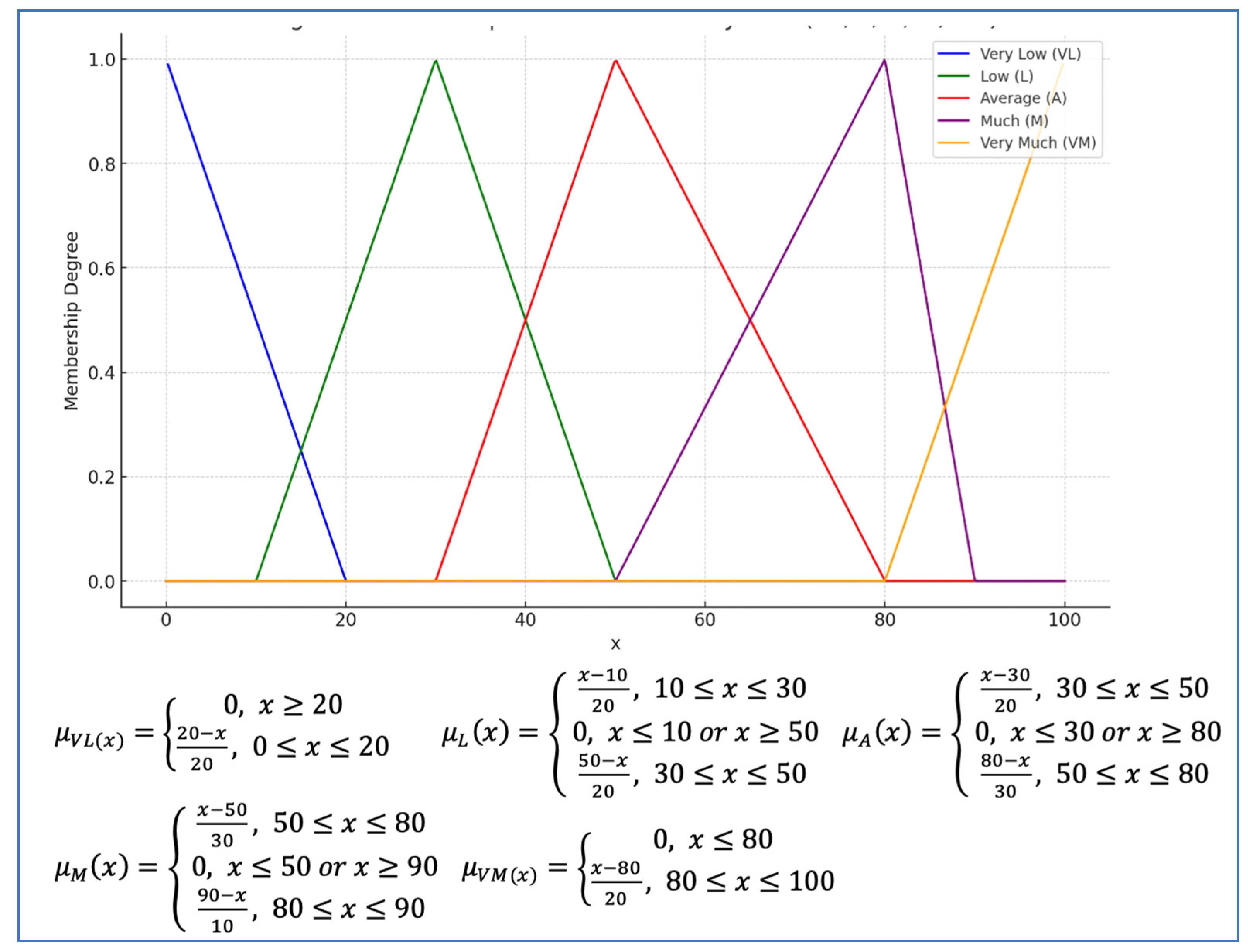

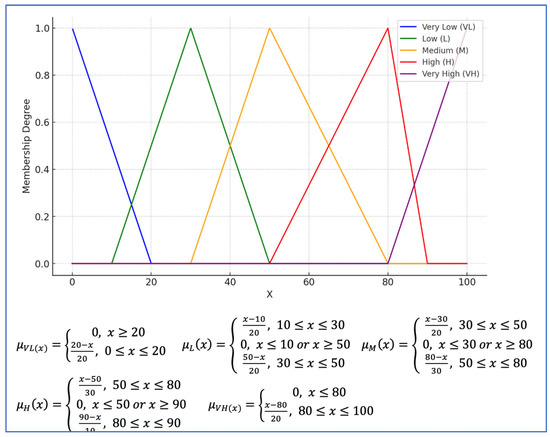

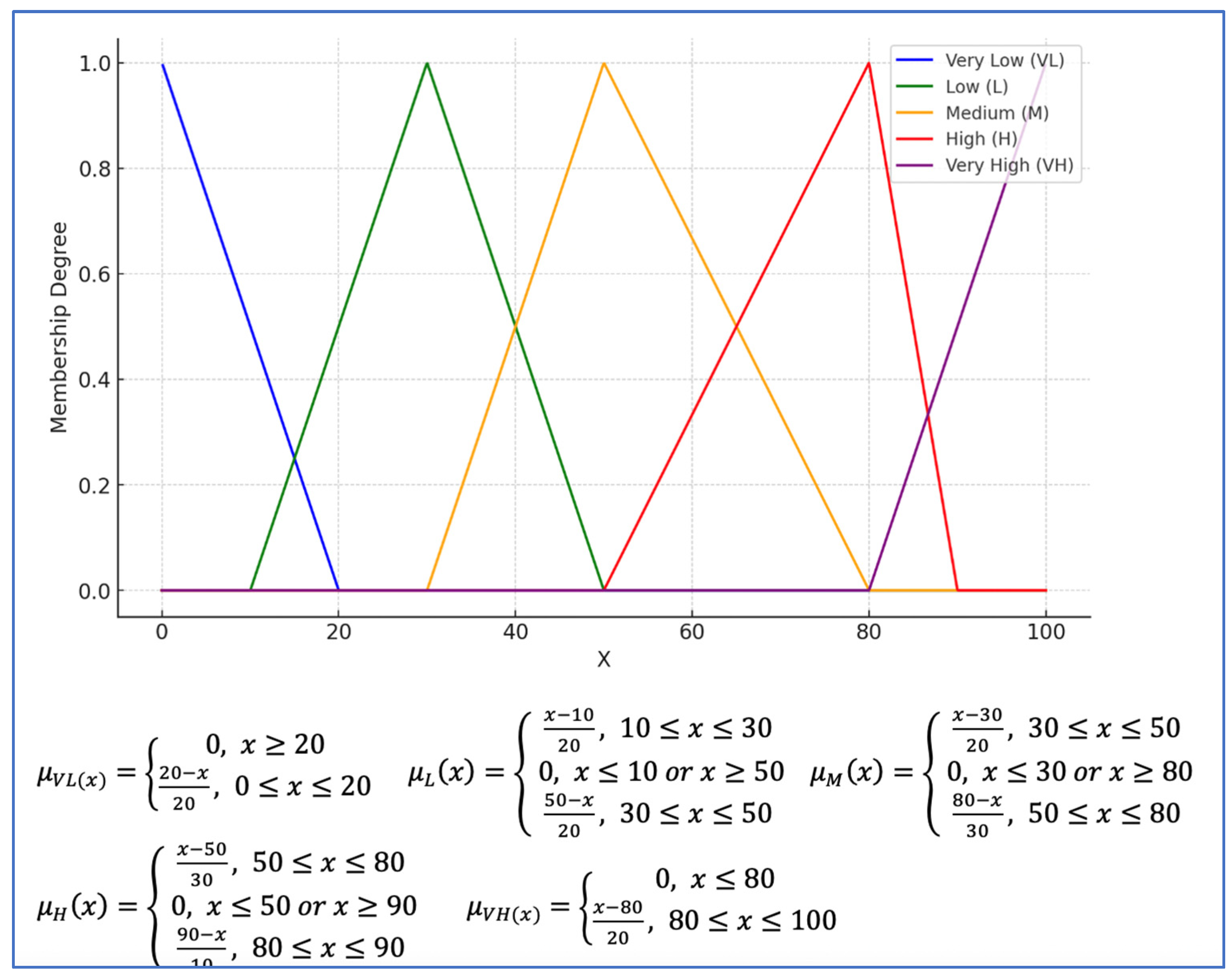

The aim of PerFuSIT is to define how significant and educationally effective each of the available tutoring strategies is for each individual learner. This significance and effectiveness are described through the following five triangular fuzzy sets (Appendix A, Figure A1): ‘Very Low’ (VL), ‘Low’ (L), ‘Average’ (A), ‘Much’ (M), and ‘Very Much’ (VM). These fuzzy sets and their intervals were determined based on the knowledge and experience of eight computer programming teachers and three intelligent tutoring system developers. All participating teachers had at least 7 years of experience in teaching computer programming, and three of them had also been involved in related computer programming curriculum development. Furthermore, the three developers had at least 5 years of experience in developing ITSs.

3.2. Input Data and Weights

The input data concern learner performance and individualized learning parameters of the learner’s profile. Particularly, the input data are as follows:

- (a)

- the learner’s degree of success (it is calculated with a maximum value of 100);

- (b)

- the learner’s syntax errors (it is calculated as the percentage of the overall errors);

- (c)

- the learner’s logical errors (it is calculated as the percentage of the overall errors);

- (d)

- the learner’s errors due to carelessness (it is calculated as the percentage of the overall errors);

- (e)

- the frequency of help requests (it is calculated as the percentage of the total available aids);

- (f)

- the mean time the learner needs to solve exercises (it is calculated as the percentage of the total available time for solving an exercise).

The crisp values of the above data are fuzzified to the following five triangular fuzzy sets: ‘Very Low’ (VL), ‘Low’ (L), ‘Medium’ (M), ‘High’ (H), and ‘Very High’ (VH). These fuzzy sets and their partitions and membership functions are presented in Figure A2 in Appendix A.

Weights are defined for each parameter and show how much each parameter (i.e., syntax errors) contributes to applying a tutoring action (i.e., providing supplemental content). A weight can have one of the following five values:

- Very low (VL): 0.1;

- Low (L): 0.3;

- Average (A): 0.5;

- Μuch (Μ): 0.8;

- Very Much (VM): 1.

For example, a very low degree of success indicates that the learner has to review the current chapter extensively, or a very high percentage of careless errors strongly implies that the learner needs to take a break. Similarly, a medium percentage of syntax errors indicates an average possibility of providing additional exercises, while a high frequency of help requests implies that the learner needs supplemental resources. The defined weights of each parameter for each tutoring strategy are presented in the tables of Appendix B. Both the fuzzy sets for the input data, as well as their weights for each input parameter, were defined by the eleven experts (eight computer programming teachers and three intelligent tutoring system developers), who were referred to in Section 3.1.

3.3. The Fuzzy Rules

Below, the PerFuSIT’s fuzzy rules are presented. For each input datum, there are 25 fuzzy sets (five rules for each tutoring strategy). There are 150 fuzzy rules in total. They are of the following format: “If ‘input_parameter’ is X then Ai is Y”, where input_parameter ∈ {degree of success, syntax errors, logical errors, carelessness errors, help requests, time to solve exercises}, X ∈ {VL, L, M, H, VH}, I ∈ [1, 5], and Y ∈ {VL, L, A, M, VM}. Some examples of the set of fuzzy rules are as follows:

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘M’ then A1 is ‘A’;

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘H’ then A3 is ‘VL’;

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘L’ then A2 is ‘M’;

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘VH’ then A5 is ‘M’;

- If ‘carelessness errors’ is ‘VH’ then A5 is ‘VM’;

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘M’ then A1 is ‘L’;

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘M’ then A3 is ‘A’.

All the rules are presented in the tables in Appendix C. Also, these rules were defined based on the experience and knowledge of the eleven experts (eight computer programming teachers and three intelligent tutoring system developers), who were referred to in Section 3.1.

3.4. The Procedure of PerFuSIT Operation

Below, the steps of the PerFuSIT’s operation are presented.

- Step 1: Definitions of the criteria weights for each tutoring strategy;

- Step 2: Obtain the values of the criteria from the log files of the system;

- Step 3: Input data fuzzification;

- Step 4: Application of the fuzzy rules;

- Step 5: Output calculation for each rule;

- Step 6: Weight application to the outputs;

- Step 7: Results aggregation;

- Step 8: Defuzzification of the aggregated result;

- Step 9: Rank the results;

- Step 10: Selection of the appropriate tutoring strategy.

4. Use Case Scenarios

In this section, examples of use clearly illustrate the operation of PerFuSIT. Let us have the following learners, whose performance and individualized learning profile parameters are presented in Table 1. The fuzzified input values for these ten learners are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1.

Learning profiles of the students.

Table 2.

Fuzzified values of the learners’ profile data.

Table 3.

Input variables’ fuzzy sets and their membership values for each learner.

Then, the fuzzy rules are applied. For example, for Maria, the following fuzzy rules are triggered:

- (1)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘M’, then A1 is ‘A’;

- (2)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘M’, then A2 is ‘L’;

- (3)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘M’, then A3 is ‘A’;

- (4)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘M’, then A4 is ‘A’;

- (5)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘M’, then A5 is ‘A’;

- (6)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘H’, then A1 is ‘L’;

- (7)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘H’, then A2 is ‘M’;

- (8)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘H’, then A3 is ‘VL’;

- (9)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘H’, then A4 is ‘VL’;

- (10)

- If ‘degree of success’ is ‘H’, then A5 is ‘VL’;

- (11)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘VL’, then A1 is ‘VL’;

- (12)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘VL’, then A2 is ‘VM’;

- (13)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘VL’, then A3 is ‘VL’;

- (14)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘VL’, then A4 is ‘VL’;

- (15)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘VL’, then A5 is ‘VL’;

- (16)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘L’, then A1 is ‘VL’;

- (17)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘L’, then A2 is ‘M’;

- (18)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘L’, then A3 is ‘VL’;

- (19)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘L’, then A4 is ‘VL’;

- (20)

- If ‘syntax errors’ is ‘L’, then A5 is ‘VL’;

- (21)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘M’, then A1 is ‘A’;

- (22)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘M’, then A2 is ‘A’;

- (23)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘M’, then A3 is ‘A’;

- (24)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘M’, then A4 is ‘M’;

- (25)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘M’, then A5 is ‘A’;

- (26)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘H’, then A1 is ‘M’;

- (27)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘H’, then A2 is ‘VL’;

- (28)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘H’, then A3 is ‘M’;

- (29)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘H’, then A4 is ‘VM’;

- (30)

- If ‘logical errors’ is ‘H’, then A5 is ‘M’;

- (31)

- If ‘carelessness errors’ is ‘VL’, then A1 is ‘VL’;

- (32)

- If ‘carelessness errors’ is ‘VL’, then A2 is ‘VL’;

- (33)

- If ‘carelessness errors’ is ‘VL’, then A3 is ‘VL’;

- (34)

- If ‘carelessness errors’ is ‘VL’, then A4 is ‘VL’;

- (35)

- If ‘carelessness errors’ is ‘VL’, then A5 is ‘VL’;

- (36)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘L’, then A1 is ‘VL’;

- (37)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘L’, then A2 is ‘M’;

- (38)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘L’, then A3 is ‘L’;

- (39)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘L’, then A4 is ‘L’;

- (40)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘L’, then A5 is ‘VL’;

- (41)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘M’, then A1 is ‘L’;

- (42)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘M’, then A2 is ‘A’;

- (43)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘M’, then A3 is ‘A’;

- (44)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘M’, then A4 is ‘A’;

- (45)

- If ‘help requests’ is ‘M’, then A5 is ‘A’;

- (46)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘M’, then A1 is ‘L’;

- (47)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘M’, then A2 is ‘A’;

- (48)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘M’, then A3 is ‘A’;

- (49)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘M’, then A4 is ‘A’;

- (50)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘M’, then A5 is ‘L’;

- (51)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘H’, then A1 is ‘A’;

- (52)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘H’, then A2 is ‘L’;

- (53)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘H’, then A3 is ‘M’;

- (54)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘H’, then A4 is ‘M’;

- (55)

- If ‘time to solve exercises’ is ‘H’, then A5 is ‘A’.

Then, the outputs of the rules are adjusted according to the weights. For example, the weight of ‘degree of success’ for A1 is very high, and for A3, it is high. Therefore, the membership values of the outputs of Rules 1 and 6 are multiplied by 1, and the membership values of the outputs of Rules 3 and 8 are multiplied by 0.8. On the other hand, the weight of ‘logical errors’ for A5 is average. Therefore, the membership values of the outputs of the corresponding rules (25 and 30) are multiplied by 0.5. Furthermore, the weight of ‘carelessness errors’ for A1 is very low, and for A4, it is low. Therefore, the membership value of the output of Rule 31 is multiplied by 0.1, and the membership value of the output of Rule 34 is multiplied by 0.3. The results of applying the fuzzy rules and the weights for the ten learners are depicted in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13. In Table 14, the final weighted outputs of the rules for all the learners are presented.

Table 4.

Fuzzy rule output for Maria.

Table 5.

Fuzzy rule output for John.

Table 6.

Fuzzy rule output for Alex.

Table 7.

Fuzzy rule output for Kate.

Table 8.

Fuzzy rule output for Jason.

Table 9.

Fuzzy rule output for Tom.

Table 10.

Fuzzy rule output for Emily.

Table 11.

Fuzzy rule output for Anna.

Table 12.

Fuzzy rule output for Lucas.

Table 13.

Fuzzy rule output for Lina.

Table 14.

Weighted outputs.

The aggregation of the rules’ outputs is performed using the centroid method. The crisp aggregated results are depicted in Table 15. According to these, Maria will be provided more practice exercises, John and Alex will progress to the next chapter of the educational content, Kate will be provided with supplemental educational resources to read, and Jason will be advised to take a break.

Table 15.

Final crisp aggregated outputs.

5. Evaluation

5.1. The Method

To evaluate PerFuSIT’s ability and effectiveness in helping learners acquire knowledge and accomplish the learning goal, an experiment was conducted. Particularly, a group of undergraduate students of informatics utilized the ITS, which incorporates PerFuSIT, for a duration of 5 weeks. Following this period, they took a test to assess the computer programming knowledge they had acquired. The test had a maximum possible score of 10, signifying an excellent level of knowledge. Furthermore, the mean number of learners’ interactions with the ITS during the period of 5 weeks was calculated by gathering the appropriate data from the log files. An interaction was recorded each time a learner read the content (standard or supplemental) of a chapter, answered the corresponding test questions, or performed supplemental exercises. For example, if a student reads a chapter three times, answers its test questions four times, and performs supplemental exercises one time before passing and moving to the next chapter, the system will count a total of eight interactions. Then, both the average performance of the learners in the abovementioned group and their mean number of interactions with the ITS were compared with the corresponding values of learners from the same undergraduate program in informatics in another group, who used another version of the ITS with the same educational content and structure but without PerFuSIT during the same period. It must be emphasized that the version of the ITS from which PerFuSIT is absent adapts the educational content to each individual learner based only on her/his performance, as is the case with most intelligent and adaptive tutoring systems [13,18,22,23,24,50,57]. For example, if a student’s performance is 42%, then the system recommends that she/he revise the current chapter of the educational material. However, if her/his degree of success is 80%, the system transits the learner to the next chapter. T-tests [58] were used to ensure the accuracy and statistical significance of the difference in the mean values of the aforementioned metrics.

5.2. The Test Bed

In the evaluation process, 114 undergraduate students of the Department of Informatics of the University of Piraeus in Greece participated. They were randomly divided into two equal-number groups: the PerFuSIT_group and No_PerFuSIT_group. The students in the first group utilized the ITS that incorporates PerFuSIT, while the No_PerFuSIT_group utilized another version of the ITS with the same educational content and structure but without the PerFuSIT. The learners in both groups utilized the systems for a period of 5 weeks. During this period, they attended lectures on computer programming. Before the students used the ITSs, they attended a detailed demonstration of them. Additionally, comprehensive user manuals were provided. Furthermore, online help and support were available throughout the usage period. There was an equal distribution between the two groups regarding the characteristics of the learners (Table 16).

Table 16.

Participants’ characteristics and their distribution.

5.3. Results

The evaluation results show that the integration of PerFuSIT enhances learners’ performance and the efficacy of their interactions with the system. Particularly, the mean performance score was 8.51 for the PerFuSIT_group and 7.02 for the No_ PerFuSIT_group (Table 17). Therefore, there is an increase of 14.9% in student performance. This increase is statistically significant since the ‘P(T ≤ t) two-tail’ value of the t-test is less than 0.05.

Table 17.

T-test results concerning the mean performance.

In addition, the average number of interactions with ITS was reduced by 15.3% with the PerFuSIT integration. In more detail, the mean number of interactions was 45.83 for PerFuSIT_group and 54.11 for No_PerFuSIT_group (Table 18). The difference in the mean number of interactions between the two groups is significant, as indicated by the value of ‘P(T ≤ t) two-tail’, which is less than 0.05. The reduction in interactions was due to the fact that through the supplemental content and exercises, the system provides more targeted educational content to students’ learning needs, so fewer interactions are needed to pass one chapter and move on to the next one. Furthermore, rest suggestions allow the learner to realize her/his fatigue and prompt her/him to interact with the system again later in order to continue the learning process with a clear mind. In this way, fatigue-related errors are prevented, and interactions are reduced.

Table 18.

T-test results concerning the mean number of interactions.

Consequently, PerFuSIT allows the learner to complete a knowledge domain chapter and reach the learning goal with fewer interactions. As a result, PerFuSIT allows learners to achieve better performance while requiring fewer interactions with the system.

6. Discussion

The development and implementation of PerFuSIT is a significant advancement in the field of adaptive learning technologies, particularly for tutoring systems for computer programming. The ability of PerFuSIT to dynamically adjust the tutoring strategies based on a variety of data in the learning profile of a student indicates a contribution to the development of more intelligent, adaptive, and effective learning systems. Unlike other intelligent tutoring systems that use fuzzy logic primarily to model student knowledge or skill levels and determine the difficulty of educational content or whether a learner should progress to the next chapter, PerFuSIT’s fuzzy inference mechanism enables real-time adjustments to more nuanced tutoring strategies, such as providing access to additional educational materials, assigning more exercises, or suggesting a break. This approach offers more targeted and responsive feedback to better support the instruction process and help learners reach the learning objectives.

To demonstrate how fuzzy rules improve the explainability of PerFuSIT’s decision-making process, consider the following scenario in an ITS: In a conventional ITS, the system might simply decide to advance a student to the next chapter based on a threshold score in a test. However, this decision offers little insight into the student’s progress and learning needs. In contrast, PerFuSIT, using fuzzy rules, provides a more nuanced explanation by considering multiple factors simultaneously, such as test scores, types of errors, carelessness, time spent, and help requests in solving exercises. Through fuzzy rules, it ‘calculates’ the appropriateness of each tutoring strategy and concludes with a decision, such as ‘The system suggests advancing to the next chapter’, ‘The system suggests to take a rest’, ‘The system suggests to read the providing supplemental content’, or ‘The system suggests to take there more supplemental exercises’, offering clearer feedback and a more interpretable decision-making process that imitates the teacher’s way of thinking.

The selection of the most appropriate tutoring strategy in our research context relies on numerous learner-specific parameters. This complexity suggests that a multicriteria decision-making (MCDM) method might be considered as an alternative approach. However, MCDM methods are most effective for problems in which criteria are well-defined, quantifiable, and have clearly established importance weights. In contrast, our problem involves factors such as performance metrics, error types, indicators of carelessness, frequency of help requests, and time required to complete tasks, which are often subjective and imprecise. These characteristics make it challenging to model the criteria comprehensively using traditional MCDM techniques.

Our fuzzy logic-based mechanism, PerFuSIT, is specifically designed to address these complexities by providing a robust and adaptive assessment of learner characteristics. This approach accommodates the inherent ambiguity and variability present in our problem—dimensions that conventional MCDM methods often find difficult to handle in a holistic and effective manner. Furthermore, in our case, the criteria do not function as static attributes of the tutoring strategies themselves. Instead, they represent dynamic, learner-specific parameters that capture the unique learning abilities and needs of each individual. These parameters influence tutoring strategy selection through interrelated and complex dynamics that are not easily represented or quantified within the rigid mathematical frameworks required by MCDM methods.

A major advantage of PerFuSIT is its explainability, which is crucial for human teachers who must understand and feel confident in the system’s decision-making process. PerFuSIT employs a sophisticated structure of fuzzy rules, which enables it to model intricate interactions among learner-specific parameters in a way that reflects expert-like reasoning. This structured yet flexible approach makes it possible to present decisions transparently, without compromising on the complexity of the underlying logic. Teachers can grasp and appreciate the rationale behind each decision, as the model is designed to parallel the thoughtful and adaptive strategies they use in real-world teaching.

This explainable nature of PerFuSIT is essential in educational settings, in which trust and comprehension are prerequisites for system adoption. By aligning closely with the reasoning and judgment processes of educators, PerFuSIT promotes collaborative and transparent integration into teaching practices. Furthermore, the system’s adaptability and capacity to model complex, interdependent factors ensure that its recommendations are not only intuitive but also scientifically sound and highly tailored to the evolving needs of individual learners.

The experimental results, which indicate improvements in both learner performance and interaction efficacy, provide strong evidence of the benefits of PerFuSIT. Particularly, PerFuSIT contributes to performance improvement and allows the learner to complete a knowledge domain chapter and reach the learning goal with fewer interactions. Therefore, it allows learners to perform better while interacting with the system fewer times. These findings underscore the significant contribution of PerFuSIT to effective learning in computer programming education. Furthermore, they highlight the potential of fuzzy logic to improve adaptive learning technologies, offering more supportive and effective personalized tutoring strategies in teaching computer programming.

However, there are some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample size limits the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, given that the experiment’s participants were undergraduate students of informatics, the sample may not fully represent the broader population. A larger and more diverse sample would help enhance the robustness and applicability of the results. Additionally, there is the potential for biases, such as differences in how adaptive features were used or accessed, which could have influenced the findings.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, PerFuSIT, an innovative fuzzy-based mechanism for providing personalized tutoring strategies within an intelligent tutoring system for computer programming, is presented. PerFuSIT takes into account several data from the students’ learning profiles and, by leveraging fuzzy logic, dynamically adapts tutoring strategies that are appropriate for each individual student. In such a way, it provides more nuanced and responsive feedback to the diverse needs of learners, thereby supporting the instructional process of computer programming.

PerFuSIT is specifically designed to tackle the complexities of modeling factors like performance metrics, error types, indicators of carelessness, frequency of help requests, and time required to complete tasks—elements that are often subjective and imprecise. Furthermore, unlike other intelligent tutoring systems that primarily use fuzzy logic to model student knowledge or skill levels and decide on content difficulty or progression to the next chapter, PerFuSIT’s fuzzy inference mechanism allows for real-time adjustments to more nuanced tutoring strategies. A key benefit of PerFuSIT is its explainability. It uses an advanced but flexible and transparent structure of fuzzy rules, allowing it to model complex interactions among learner-specific parameters. These rules simulate the experts’ way of reasoning about tutoring strategies in real-world teaching.

The experimental results confirm that PerFuSIT contributes to improved learner performance and more efficient interactions within the tutoring system. These findings highlight the value of incorporating fuzzy logic into adaptive learning technologies, particularly in environments in which learners have diverse needs and learning paces. They indicate that PerFuSIT constitutes a major advancement in the development of intelligent tutoring systems for computer programming. This can also influence the wider field of personalized education. Furthermore, the presented mechanism can be leveraged to develop more intelligent, adaptive, and effective learning systems.

In the future, emotional and motivational indicators in the learners’ needs must be taken into consideration to provide a more advanced personalized tutoring process. Also, machine learning techniques can be combined with fuzzy logic for the automatic definition of several system parameters and thresholds. Furthermore, we intend to incorporate PerFuSIT into ITSs of more domain knowledge, not only computer programming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C. and M.V.; methodology, K.C.; software, K.C.; validation, K.C. and M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C.; visualization, K.C.; supervision, M.V.; project administration, K.C. and M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study involves the analysis of data sets obtained during lessons of the members of the authors’ team. It was conducted in accordance with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). All participants were informed about their anonymity assurance, the purpose of the research and how their data will be used.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Fuzzy sets for tutoring strategy significance.

Figure A1.

Fuzzy sets for tutoring strategy significance.

Figure A2.

Fuzzy sets for input variables of PerFuSIT.

Figure A2.

Fuzzy sets for input variables of PerFuSIT.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Weights of the degree of success for each tutoring strategy.

Table A1.

Weights of the degree of success for each tutoring strategy.

| Degree | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VM | M | A | L | VL |

| A2 | VL | VL | L | M | VM |

| A3 | M | M | A | VL | VL |

| A4 | L | L | A | VL | VL |

| A5 | M | M | A | VL | VL |

Table A2.

Weights of syntax errors for each tutoring strategy.

Table A2.

Weights of syntax errors for each tutoring strategy.

| Syntax | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | A | M | VM |

| A2 | VM | M | A | VL | VL |

| A3 | VL | VL | L | A | A |

| A4 | VL | VL | A | M | M |

| A5 | VL | VL | A | M | M |

Table A3.

Weights of logical errors for each tutoring strategy.

Table A3.

Weights of logical errors for each tutoring strategy.

| Logical | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | A | M | VM |

| A2 | VM | M | A | VL | VL |

| A3 | VL | L | A | M | VM |

| A4 | VL | L | M | VM | VM |

| A5 | VL | VL | A | M | M |

Table A4.

Weights of carelessness errors for each tutoring strategy.

Table A4.

Weights of carelessness errors for each tutoring strategy.

| Carelessness | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | VL | L | L |

| A2 | VL | VL | VL | VL | VL |

| A3 | VL | VL | VL | VL | VL |

| A4 | VL | VL | M | M | M |

| A5 | VL | VL | M | VM | VM |

Table A5.

Weights of help requests for each tutoring strategy.

Table A5.

Weights of help requests for each tutoring strategy.

| Help Requests | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | L | A | A |

| A2 | M | M | A | L | VL |

| A3 | VL | L | A | M | VM |

| A4 | VL | L | A | M | VM |

| A5 | VL | VL | L | M | M |

Table A6.

Weights of required time to solve exercises for each tutoring strategy.

Table A6.

Weights of required time to solve exercises for each tutoring strategy.

| Time | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | L | A | A |

| A2 | M | A | A | L | L |

| A3 | VL | VL | A | M | VM |

| A4 | VL | VL | A | M | VM |

| A5 | VL | VL | L | A | M |

Appendix C

Table A7.

Fuzzy rules concerning the degree of success.

Table A7.

Fuzzy rules concerning the degree of success.

| Degree of Success | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VM | M | A | L | VL |

| A2 | VL | VL | L | M | VM |

| A3 | M | M | A | VL | VL |

| A4 | L | L | A | VL | VL |

| A5 | M | M | A | VL | VL |

Table A8.

Fuzzy rules concerning syntax errors.

Table A8.

Fuzzy rules concerning syntax errors.

| Syntax Errors | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | A | M | VM |

| A2 | VM | M | A | VL | VL |

| A3 | VL | VL | L | A | A |

| A4 | VL | VL | A | M | M |

| A5 | VL | VL | A | M | M |

Table A9.

Fuzzy rules concerning logical errors.

Table A9.

Fuzzy rules concerning logical errors.

| Logical Errors | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | A | M | VM |

| A2 | VM | M | A | VL | VL |

| A3 | VL | L | A | M | VM |

| A4 | VL | L | M | VM | VM |

| A5 | VL | VL | A | M | M |

Table A10.

Fuzzy rules concerning carelessness errors.

Table A10.

Fuzzy rules concerning carelessness errors.

| Carelessness Errors | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | VL | L | L |

| A2 | VL | VL | VL | VL | VL |

| A3 | VL | VL | VL | VL | VL |

| A4 | VL | VL | M | M | M |

| A5 | VL | VL | M | VM | VM |

Table A11.

Fuzzy rules concerning help requests.

Table A11.

Fuzzy rules concerning help requests.

| Help Requests | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | L | A | A |

| A2 | M | M | A | L | VL |

| A3 | VL | L | A | M | VM |

| A4 | VL | L | A | M | VM |

| A5 | VL | VL | L | M | M |

Table A12.

Fuzzy rules concerning required time to solve exercises.

Table A12.

Fuzzy rules concerning required time to solve exercises.

| Time to Solve Exercises | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | VL | VL | L | A | A |

| A2 | M | A | A | L | L |

| A3 | VL | VL | A | M | VM |

| A4 | VL | VL | A | M | VM |

| A5 | VL | VL | L | A | M |

References

- Goenaga, S.; Navarro, L.; Quintero, M.C.G.; Pardo, M. Imitating human emotions with a nao robot as interviewer playing the role of vocational tutor. Electronics 2020, 9, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minn, S. AI-assisted knowledge assessment techniques for adaptive learning environments. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrakhawi, H.A.; Jamiat, N.; Abu-Naser, S.S. Intelligent tutoring systems in education: A systematic review of usage, tools, effects and evaluation. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2023, 101, 1205–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Alrakhawi, H.A.; Jamiat, N.; Umar, I.N.; Abu-Naser, S.S. Improvement of Students Achievement by Using Intelligent Tutoring Systems-A Bibliometric Analysis and Reviews. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2023, 101, 3793–3800. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.M.M.; Voelzke, M.R. Adaptive Learning the Use of the Khan Platform Academy in Mathematics Teaching. Proc. Forum Metodol. Ativas 2021, 3, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, G.; Spaulding, S.; Kory Westlund, J.; Lee, J.J.; Plummer, L.; Martinez, M.; Das, M.; Breazeal, C. Affective Personalization of a Social Robot Tutor for Children’s Second Language Skills. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2016, 30, 3951–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessingh, J.J.; Poppinga, G.; van Oijen, J.; Toubman, A. Application of artificial intelligence to adaptive instruction-combining the concepts. In Adaptive Instructional Systems: First International Conference, AIS 2019, Held as Part of the 21st HCI International Conference, HCII 2019, Orlando, FL, USA, 26–31 July 2019; Proceedings 21; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 542–556. [Google Scholar]

- Sottilare, R. Agent-based methods in support of adaptive instructional decisions. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 164–175. [Google Scholar]

- AlShaikh, F.; Hewahi, N. AI and machine learning techniques in the development of Intelligent Tutoring System: A review. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies, Zallaq, Bahrain, 29–30 September 2021; pp. 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Tran, T.; Du, Z. Artificial intelligence in education: A systematic literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, I.; Kuk, K.; Čisar, P.; Banđur, M.; Banđur, Đ.; Milić, N.; Popović, B. Multi-agent system observer: Intelligent support for engaged e-learning. Electronics 2021, 10, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Cota, C.; Molina, A.I.; Redondo, M.A.; Lacave, C. Individual differences in computer programming: A systematic review. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacave, C.; Molina, A.I. The Impact of COVID-19 in Collaborative Programming. Understanding the Needs of Undergraduate Computer Science Students. Electronics 2021, 10, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshyar, D.; Binti Ahmad, R.; Wang, M.; Yousefi, M.; Fathi, M.; Lim, H. Development and evaluation of a game-based bayesian intelligent tutoring system for teaching programming. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2018, 56, 775–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, J.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Intelligent tutoring systems approach to introductory programming courses. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, Salamanca, Spain, 21–23 October 2020; pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysafiadi, K.; Virvou, M.; Tsihrintzis, G.A. A fuzzy-based evaluation of E-learning acceptance and effectiveness by computer science students in Greece in the period of COVID-19. Electronics 2023, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Schez, J.J.; Glez-Morcillo, C.; Albusac, J.; Vallejo, D. An intelligent tutoring system for supporting active learning: A case study on predictive parsing learning. Inf. Sci. 2021, 544, 446–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesin, B.; Mangaroska, K.; Akhuseyinoglu, K.; Giannakos, M. Adaptive assessment and content recommendation in online programming courses: On the use of elo-rating. ACM Trans. Comput. Educ. TOCE 2022, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Petegem, C.; Dawyndt, P.; Mesuere, B. Dodona: Learn to code with a virtual co-teacher that supports active learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education, Turku, Finland, 7–15 July 2023; Volume 2, p. 633. [Google Scholar]

- Day, M.; Penumala, M.R.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, J. Annete: An intelligent tutoring companion embedded into the eclipse IDE. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE First International Conference on Cognitive Machine Intelligence (CogMI), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 12–14 December 2019; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Brusilovsky, P.; Guerra, J.; Koedinger, K.; Schunn, C. Supporting skill integration in an intelligent tutoring system for code tracing. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2023, 39, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkot, M.A. Embedding adaptation levels within intelligent tutoring systems for developing programming skills and improving learning efficiency. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, R.E.; de Oliveira Silva, F. Intelligent Tutoring System for Computer Science Education and the Use of Artificial Intelligence: A Literature Review. CSEDU 2022, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, T.; Luxton-Reilly, A.; Wuensche, B. Intelligent tutoring systems for programming education: A systematic review. In Proceedings of the 20th Australasian Computing Education Conference, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 30 January–2 February 2018; pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, R.P.; Ramalho, G.L.; Falcão, T.P. A systematic literature review on teaching and learning introductory programming in higher education. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2019, 62, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacave, C.; Molina, A.I.; Cruz-Lemus, J.A. Learning Analytics to identify dropout factors of Computer Science studies through Bayesian networks. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 993–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirzyte, A.; Perminas, A.; Kaminskis, L.; Žebrauskas, G.; Sederevičiūtė-Pačiauskienė, Ž.; Šliogerienė, J.; Gajdosikiene, I. Factors contributing to dropping out of adults’ programming e-learning. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulianto, B.; Prabowo, H.; Kosala, R. Comparing the effectiveness of digital contents for improving learning outcomes in computer programming for autodidact students. J. e-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2016, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinovieva, I.S.; Artemchuk, V.O.; Iatsyshyn, A.V.; Popov, O.O.; Kovach, V.O.; Iatsyshyn, A.V.; Radchenko, O.V. The use of online coding platforms as additional distance tools in programming education. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1840, 12029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, M.C.; Baker, R.S.D. A review of recent advances in learner and skill modeling in intelligent learning environments. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2012, 22, 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, H.T.; Trung, N.Q.; Duy, B.T. Responsive student model in an intelligent tutoring system and its evaluation. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 4969–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Noriega, A.; Juárez-Ramírez, R.; Jiménez, S.; Martínez-Ramírez, Y. Knowledge representation in intelligent tutoring system. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics 2016; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Le, N.T.; Pinkwart, N. Adding weights to constraints in intelligent tutoring systems: Does it improve the error diagnosis? In Proceedings of the Towards Ubiquitous Learning: 6th European Conference of Technology Enhanced Learning, EC-TEL 2011, Palermo, Italy, 20–23 September 2011; Proceedings 6; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 233–247.

- McCall, D. Novice Programmer Errors-Analysis and Diagnostics; University of Kent: Canterbury, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jamaludin, N.H.; Romli, R. Analysis of the Effectiveness of Feedback Provision in Intelligent Tutoring Systems. In International Conference on Computing and Informatics; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 168–179. [Google Scholar]

- Keuning, H.; Jeuring, J.; Heeren, B. A systematic literature review of automated feedback generation for programming exercises. ACM Trans. Comput. Educ. TOCE 2018, 19, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysafiadi, K. The Role of Fuzzy Logic in Artificial Intelligence and Smart Applications. In Fuzzy Logic-Based Software Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysafiadi, K.; Papadimitriou, S.; Virvou, M. Cognitive-based adaptive scenarios in educational games using fuzzy reasoning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 250, 109111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.X.; Gong, H.P.; Liu, H.C.; Mou, X. Knowledge representation and reasoning using fuzzy Petri nets: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 6241–6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaci, A. Intelligent tutoring system model based on fuzzy logic and constraint-based student model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 3619–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysafiadi, K.; Virvou, M. Evaluating the learning outcomes of a fuzzy-based Intelligent Tutoring System. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 33rd International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Washington, DC, USA, 1–3 November 2021; pp. 1392–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, T.-C.; Lee, M.-C.; Su, C.-Y. Designing and implementing a personalized remedial learning system for enhancing the programming learning. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2013, 16, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter, J.W.; Abdelshiheed, M.; Barnes, T.; Chi, M. Leveraging fuzzy logic towards more explainable reinforcement learning-induced pedagogical policies on intelligent tutoring systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ), Incheon, Republic of Korea, 13–17 August 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lasfeto, D.B.; Ulfa, S. Modeling of online learning strategies based on fuzzy expert systems and self-directed learning readiness: The effect on learning outcomes. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2023, 60, 2081–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lemos, R.; Giese, H.; Müller, H.A.; Shaw, M.; Andersson, J.; Litoiu, M.; Schmerl, B.; Tamura, G.; Villegas, N.M.; Vogel, T.; et al. Software engineering for self-adaptive systems: A second research roadmap. In Proceedings of the Software Engineering for Self-Adaptive Systems II: International Seminar, Dagstuhl Castle, Germany, 24–29 October 2010; Revised Selected and Invited Papers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bucchiarone, A.; Mongiello, M. Ten Years of Self-adaptive Systems: From Dynamic Ensembles to Collective Adaptive Systems. In From Software Engineering to Formal Methods and Tools, and Back; Ter Beek, M., Fantechi, A., Semini, L., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinescu, R.; Mirandola, R.; Perez-Palacin, D.; Weyns, D. Understanding Uncertainty in Self-adaptive Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Autonomic Computing and Self-Organizing Systems (ACSOS), Washington, DC, USA, 17–21 August 2020; pp. 242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalerchuk, B. Quest for rigorous intelligent tutoring systems under uncertainty: Computing with Words and Images. In Proceedings of the 2013 Joint IFSA World Congress and NAFIPS Annual Meeting (IFSA/NAFIPS), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–28 June 2013; pp. 685–690. [Google Scholar]

- Yazid, M.A.A.F.M.; Sahabudin, N.A.; Raffei, A.F.M.; Remli, M.A. C Programming Skill Levels Determination Using Fuzzy Logic. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Software Engineering & Computer Systems and 4th International Conference on Computational Science and Information Management (ICSECS-ICOCSIM), Pekan, Malaysia, 24–26 August 2021; 2021; pp. 399–404. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, C.; Licea, G.; García-Valdez, M.; Quezada, A.; Castañón-Puga, M. Teaching Computer Programming as Well-Defined Domain for Beginners with Protoboard. In Trends and Innovations in Information Systems and Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado, F.; Redondo, M.A.; Ortega, M. Using fuzzy logic applied to software metrics and test cases to assess programming assignments and give advice. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2012, 35, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysafiadi, K.; Virvou, M. Fuzzy logic for adaptive instruction in an e-learning environment for computer programming. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2014, 23, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toukiloglou, P.; Xinogalos, S. NanoDoc: Designing an adaptive serious game for programming with working examples support. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Games Based Learning, Lisbon, Portuga, 6–7 October 2022; Volume 16, pp. 628–636. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, S.; Chrysafiadi, K.; Virvou, M. FuzzEG: Fuzzy logic for adaptive scenarios in an educational adventure game. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 32023–32053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahldick, A.; Mendes, A.J.; Marcelino, M.J. Dynamic difficulty adjustment through a learning analytics model in a casual serious game for computer programming learning. EAI Endorsed Trans. Serious Games 2017, 4, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mousavinasab, E.; Zarifsanaiey, N.; Niakan Kalhori, S.R.; Rakhshan, M.; Keikha, L.; Ghazi Saeedi, M. Intelligent tutoring systems: A systematic review of characteristics, applications, and evaluation methods. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).