Comparing Relationship Satisfaction and Body-Image-Related Quality of Life in Pregnant Women with Planned and Unplanned Pregnancies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Analysis of Surveys

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Background Analysis

3.2. Analysis of Unstandardized Surveys

3.3. Analysis of Standardized Surveys

3.4. Risk Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Literature Findings

4.2. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delgado-Ron, J.A.; Janus, M. Association between pregnancy planning or intention and early child development: A systematic scoping review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0002636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosen, B.; Dauria, E.; Shumway, M.; Smith, J.D.; Koinis-Mitchell, D.; Tolou-Shams, M. Association of pregnancy attitudes and intentions with sexual activity and psychiatric symptoms in justice-involved youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 138, 106510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Muskens, L.; Boekhorst, M.G.B.M.; Kop, W.J.; Heuvel, M.I.v.D.; Pop, V.J.M.; Beerthuizen, A. The association of unplanned pregnancy with perinatal depression: A longitudinal cohort study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2022, 25, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bahk, J.; Yun, S.-C.; Kim, Y.-M.; Khang, Y.-H. Impact of unintended pregnancy on maternal mental health: A causal analysis using follow up data of the Panel Study on Korean Children (PSKC). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barton, K.; Redshaw, M.; Quigley, M.A.; Carson, C. Unplanned pregnancy and subsequent psychological distress in partnered women: A cross-sectional study of the role of relationship quality and wider social support. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Carrasco, F.J.; Batugg-Chaves, C.; Ruger-Navarrete, A.; Riesco-González, F.J.; Palomo-Gómez, R.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Diaz, L.R.; Vázquez-Lara, M.D.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Vázquez-Lara, J.M. Influence of Pregnancy on Sexual Desire in Pregnant Women and Their Partners: Systematic Review. Public Health Rev. 2024, 44, 1606308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daescu, A.-M.C.; Navolan, D.-B.; Dehelean, L.; Frandes, M.; Gaitoane, A.-I.; Daescu, A.; Daniluc, R.-I.; Stoian, D. The Paradox of Sexual Dysfunction Observed during Pregnancy. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Branecka-Woźniak, D.; Wójcik, A.; Błażejewska-Jaśkowiak, J.; Kurzawa, R. Sexual and Life Satisfaction of Pregnant Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arteaga, S.; Caton, L.; Gomez, A.M. Planned, unplanned and in-between: The meaning and context of pregnancy planning for young people. Contraception 2019, 99, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Enthoven, C.A.; El Marroun, H.; Koopman-Verhoeff, M.E.; Jansen, W.; Berg, M.P.L.-V.D.; Sondeijker, F.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; Bijma, H.H.; Jansen, P.W. Clustering of characteristics associated with unplanned pregnancies: The generation R study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Røsand, G.-M.B.; Slinning, K.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; Røysamb, E.; Tambs, K. Partner relationship satisfaction and maternal emotional distress in early pregnancy. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Phiri, T.M.; Nyamaruze, P.; Akintola, O. Perspectives about social support among unmarried pregnant university students in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson, M.D.; Lavner, J.A.; Mund, M.; Zemp, M.; Stanley, S.M.; Neyer, F.J.; Impett, E.A.; Rhoades, G.K.; Bodenmann, G.; Weidmann, R.; et al. Within-Couple Associations Between Communication and Relationship Satisfaction over Time. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 48, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Cho, J. The dynamics of social support and affective well-being before and during COVID: An experience sampling study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garthus-Niegel, S.; Horsch, A.; Handtke, E.; von Soest, T.; Ayers, S.; Weidner, K.; Eberhard-Gran, M. The Impact of Postpartum Posttraumatic Stress and Depression Symptoms on Couples’ Relationship Satisfaction: A Population-Based Prospective Study. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bînă, A.M.; Aburel, O.M.; Avram, V.F.; Lelcu, T.; Lința, A.V.; Chiriac, D.V.; Mocanu, A.G.; Bernad, E.; Borza, C.; Craina, M.L.; et al. Impairment of mitochondrial respiration in platelets and placentas: A pilot study in preeclamptic pregnancies. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 477, 1987–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ciuca, I.M.; Dediu, M.; Popin, D.; Pop, L.L.; Tamas, L.A.; Pilut, C.N.; Guta, B.A.; Popa, Z.L. Antibiotherapy in Children with Cystic Fibrosis-An Extensive Review. Children 2022, 9, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dale, M.T.G.; Solberg, Ø.; Holmstrøm, H.; Landolt, M.A.; Eskedal, L.T.; Vollrath, M.E. Relationship satisfaction among mothers of children with congenital heart defects: A prospective case-cohort study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bînă, A.M.; Sturza, A.; Iancu, I.; Mocanu, A.G.; Bernad, E.; Chiriac, D.V.; Borza, C.; Craina, M.L.; Popa, Z.L.; Muntean, D.M.; et al. Placental oxidative stress and monoamine oxidase expression are increased in severe preeclampsia: A pilot study. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 477, 2851–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stelea, L.; Chiriac, V.D.; Craina, M.; Petre, I.; Popa, Z.; Vlaicu, B.; Iacob, D.; Moleriu, L.C.; Ivan, M.V.; Pop, E.; et al. Transvaginal Cystocele Repair Using Tension-free Polypropylene Mesh (Tension-free Vaginal Tape). Mater. Plast. 2018, 55, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdős, C.; Kelemen, O.; Pócs, D.; Horváth, E.; Dudás, N.; Papp, A.; Paulik, E. Female Sexual Dysfunction in Association with Sexual History, Sexual Abuse and Satisfaction: A Cross-Sectional Study in Hungary. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Starc, A.; Jukić, T.; Poljšak, B.; Dahmane, R. Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction: A Cross-National Prevalence Study in Slovenia. Acta Clin. Croat. 2018, 57, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alidost, F.; Pakzad, R.; Dolatian, M.; Abdi, F. Sexual dysfunction among women of reproductive age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2021, 19, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wiegel, M.; Meston, C.; Rosen, R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2005, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cragun, D.; DeBate, R.D.; Ata, R.N.; Thompson, J.K. Psychometric properties of the Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults in an early adolescent sample. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2013, 18, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, B.; Navarro-Brazález, B.; Arranz-Martín, B.; Sánchez-Méndez, Ó.; de la Rosa-Díaz, I.; Torres-Lacomba, M. The Female Sexual Function Index: Transculturally Adaptation and Psychometric Validation in Spanish Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 994, Erratum in Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.B.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R., Jr. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.G.; Garbett, K.M.; Matheson, E.L.; Amaral, A.C.S.; Meireles, J.F.F.; Almeida, M.C.; Hayes, C.; Vitoratou, S.; Diedrichs, P.C. The Body Esteem Scale for Adults and Adolescents: Translation, adaptation and psychometric validation among Brazilian adolescents. Body Image 2022, 42, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelson, B.K.; Mendelson, M.J.; White, D.R. Body-esteem scale for adolescents and adults. J. Pers. Assess. 2001, 76, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G. Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II) [Database Record]; APA PsycTests; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Why after 50 years of effective contraception do we still have unintended pregnancy? A European perspective. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellings, K.; Jones, K.G.; Mercer, C.H.; Tanton, C.; Clifton, S.; Datta, J.; Copas, A.J.; Erens, B.; Gibson, L.J.; Macdowall, W.; et al. The prevalence of unplanned pregnancy and associated factors in Britain: Findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet 2013, 382, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sarder, A.; Islam, S.M.S.; Maniruzzaman; Talukder, A.; Ahammed, B. Prevalence of unintended pregnancy and its associated factors: Evidence from six south Asian countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245923, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daescu, A.-M.C.; Dehelean, L.; Navolan, D.-B.; Gaitoane, A.-I.; Daescu, A.; Stoian, D. Effects of Hormonal Profile, Weight, and Body Image on Sexual Function in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.A.; Hirsch, J.S.; Trussell, J. Pleasure, prophylaxis and procreation: A qualitative analysis of intermittent contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2008, 40, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koolaee, A.K.; Zamani, M.; Moslanejad, L.; Jamali, S. Comparison of sexual activity and life satisfaction in women with intended and unintended pregnancies. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2016, 14, 63–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barrow, A.; Jobe, A.; Barrow, S.; Touray, E.; Ekholuenetale, M. Prevalence and factors associated with unplanned pregnancy in The Gambia: Findings from 2018 population-based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gianotten, W.L. Sexual Aspects of Getting Pregnant (Conception and Preconception). In Midwifery and Sexuality; Geuens, S., Polona Mivšek, A., Gianotten, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Planned Pregnancy (n = 59) | Unplanned Pregnancy (n = 48) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 28.5 ± 5.2 | 27.3 ± 4.8 | 0.257 |

| Level of education, n (%) | 0.082 | ||

| Elementary | 12 (20.34%) | 15 (31.25%) | |

| Mid-level | 22 (37.29%) | 20 (41.67%) | |

| Higher education | 25 (42.37%) | 13 (27.08%) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | |||

| First trimester | 23.1 ± 2.9 | 24.5 ± 3.2 | 0.019 |

| Second trimester | 24.4 ± 3.1 | 25.2 ± 3.5 | 0.037 |

| Third trimester | 25.7 ± 3.4 | 26.1 ± 3.6 | 0.158 |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 8 (13.56%) | 10 (20.83%) | 0.215 |

| Below-average income, n (%) | 15 (25.42%) | 19 (39.58%) | 0.073 |

| Rural living area, n (%) | 20 (33.90%) | 25 (52.08%) | 0.034 |

| Unmarried civil status, n (%) | 9 (15.25%) | 14 (29.17%) | 0.045 |

| Previous abortion, n (%) | 5 (8.47%) | 12 (25.00%) | 0.012 |

| Irregular menstrual cycle, n (%) | 11 (18.64%) | 17 (35.42%) | 0.026 |

| Contraceptive use, n (%) | 0.005 | ||

| No | 19 (32.20%) | 28 (58.33%) | |

| <1 year | 15 (25.42%) | 8 (16.67%) | |

| 1–5 years | 20 (33.90%) | 10 (20.83%) | |

| >5 years | 5 (8.48%) | 2 (4.17%) |

| Variables (Mean ± SD) | Planned Pregnancy (n = 59) | Unplanned Pregnancy (n = 48) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall satisfaction with current relationship (1–5 scale) | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 0.094 |

| Satisfaction with partner support (1–5 scale) | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 0.041 |

| Satisfaction with communication in couple (1–5 scale) | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 0.020 |

| Satisfaction with emotional closeness (1–5 scale) | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 0.004 |

| Satisfaction with current pregnancy adaptation (yes, %) | 88.14% (52) | 81.25% (39) | 0.158 |

| Ability to maintain daily activities due to physical changes from pregnancy (yes, %) | 76.27% (45) | 75.00% (36) | 0.812 |

| Ability to maintain daily activities due to psychological changes from pregnancy (yes, %) | 81.36% (48) | 68.75% (33) | 0.037 |

| Concerns about managing professional activities and household chores during pregnancy (yes, %) | 33.90% (20) | 62.50% (30) | 0.014 |

| Concerns about successfully carrying pregnancy to term (yes, %) | 25.42% (15) | 58.33% (28) | 0.003 |

| Worries about coping with labor and/or birth (yes, %) | 30.51% (18) | 56.25% (27) | 0.001 |

| Variables (Median-IQR) | Planned Pregnancy (n = 59) | Unplanned Pregnancy (n = 48) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| First trimester | |||

| Desire | 3.6 (2.8–4.4) | 4.7 (3.6–5.8) | 0.005 |

| Arousal | 3.8 (3.1–4.3) | 4.5 (4.0–5.3) | 0.001 |

| Lubrication | 3.7 (2.9–4.5) | 4.6 (4.1–5.1) | 0.015 |

| Orgasm | 3.5 (2.7–4.3) | 4.0 (3.4–4.8) | 0.061 |

| Satisfaction | 3.9 (3.1–4.7) | 4.8 (4.2–5.2) | 0.009 |

| Pain | 4.0 (3.2–4.8) | 3.9 (3.3–5.3) | 0.282 |

| Total | 26.5 (23.4–28.6) | 29.1 (24.0–31.2) | 0.006 |

| Second trimester | |||

| Desire | 4.0 (3.4–4.6) | 4.5 (4.1–4.9) | 0.063 |

| Arousal | 4.2 (3.6–4.7) | 4.8 (4.3–5.3) | 0.019 |

| Lubrication | 4.3 (3.7–4.9) | 5.0 (4.5–5.5) | 0.011 |

| Orgasm | 4.0 (3.4–4.8) | 4.6 (4.1–5.1) | 0.097 |

| Satisfaction | 4.4 (3.8–4.9) | 5.0 (4.6–5.4) | 0.008 |

| Pain | 4.5 (3.9–5.1) | 4.1 (3.6–5.6) | 0.214 |

| Total | 25.4 (23.8–27.0) | 28.2 (26.2–30.8) | 0.005 |

| Third trimester | |||

| Desire | 3.8 (3.2–4.4) | 4.4 (4.0–4.8) | 0.039 |

| Arousal | 4.1 (3.5–4.7) | 4.3 (3.8–5.2) | 0.118 |

| Lubrication | 4.2 (3.6–4.8) | 4.9 (3.9–5.4) | 0.013 |

| Orgasm | 3.9 (3.3–4.5) | 4.5 (4.0–5.0) | 0.025 |

| Satisfaction | 4.3 (3.7–4.9) | 5.0 (4.5–5.3) | 0.010 |

| Pain | 4.4 (3.8–5.0) | 4.6 (3.5–5.5) | 0.186 |

| Total | 24.7 (22.9–26.5) | 27.4 (25.6–29.2) | 0.007 |

| Variables (Median-IQR) | Planned Pregnancy Group | p-Value | Unplanned Pregnancy Group | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Trimester | Second Trimester | Third Trimester | First Trimester | Second Trimester | Third Trimester | |||

| Desire | 3.6 (2.8–4.4) | 4.0 (3.4–4.6) | 3.8 (3.2–4.4) | 0.286 | 4.7 (3.6–5.8) | 4.5 (4.1–4.9) | 4.4 (4.0–4.8) | 0.080 |

| Arousal | 3.8 (3.1–4.3) | 4.2 (3.6–4.7) | 4.1 (3.5–4.7) | 0.091 | 4.5 (4.0–5.3) | 4.8 (4.3–5.3) | 4.3 (3.8–5.2) | 0.219 |

| Lubrication | 3.7 (2.9–4.5) | 4.3 (3.7–4.9) | 4.2 (3.6–4.8) | 0.133 | 4.6 (4.1–5.1) | 5.0 (4.5–5.5) | 4.9 (3.9–5.4) | 0.126 |

| Orgasm | 3.5 (2.7–4.3) | 4.0 (3.4–4.8) | 3.9 (3.3–4.5) | 0.320 | 4.0 (3.4–4.8) | 4.6 (4.1–5.1) | 4.5 (4.0–5.0) | 0.183 |

| Satisfaction | 3.9 (3.1–4.7) | 4.4 (3.8–4.9) | 4.3 (3.7–4.9) | 0.308 | 4.8 (4.2–5.2) | 5.0 (4.6–5.4) | 5.0 (4.5–5.3) | 0.592 |

| Pain | 4.0 (3.2–4.8) | 4.5 (3.9–5.1) | 4.4 (3.8–5.0) | 0.126 | 3.9 (3.3–5.3) | 4.1 (3.6–5.6) | 4.6 (3.5–5.5) | 0.066 |

| Total | 26.5 (23.4–28.6) | 25.4 (23.8–27.0) | 24.7 (22.9–26.5) | 0.075 | 29.1 (24.0–31.2) | 28.2 (26.2–30.8) | 27.4 (25.6–29.2) | 0.133 |

| Variables (Median-IQR) | Planned Pregnancy (n = 59) | Unplanned Pregnancy (n = 48) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BESAQ | |||

| First trimester | 0.74 (0.46–1.03) | 0.72 (0.38–0.99) | 0.823 |

| Second trimester | 0.81 (0.52–1.19) | 0.77 (0.39–1.05) | 0.687 |

| Third trimester | 0.79 (0.41–1.07) | 0.80 (0.32–1.08) | 0.954 |

| BDI | |||

| First trimester | 4.02 (3.38–6.42) | 6.76 (3.24–9.62) | 0.037 |

| Second trimester | 5.13 (2.88–7.34) | 5.89 (4.22–9.11) | 0.143 |

| Third trimester | 6.47 (3.19–8.56) | 7.35 (4.68–10.29) | 0.097 |

| Variables (Median-IQR) | Planned Pregnancy Group | p-Value | Unplanned Pregnancy Group | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Trimester | Second Trimester | Third Trimester | First Trimester | Second Trimester | Third Trimester | |||

| BESAQ | 0.74 (0.46–1.03) | 0.81 (0.52–1.19) | 0.79 (0.41–1.07) | 0.256 | 0.72 (0.38–0.99) | 0.77 (0.39–1.05) | 0.80 (0.32–1.08) | 0.194 |

| BDI | 4.02 (3.38–6.42) | 5.13 (2.88–7.34) | 5.47 (3.19–8.56) | 0.312 | 6.76 (3.24–9.62) | 5.89 (4.22–9.11) | 7.35 (4.68–10.29) | 0.257 |

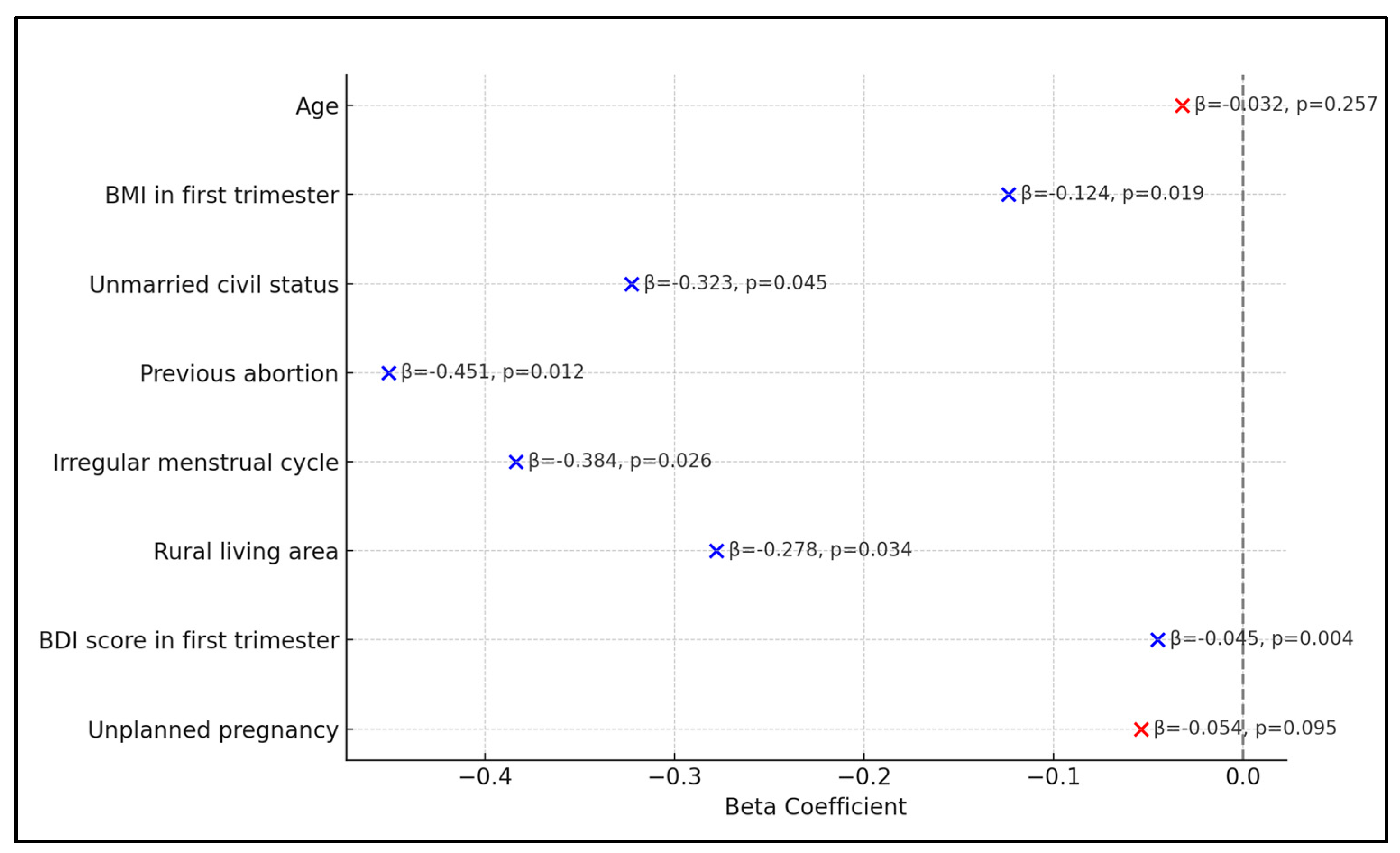

| Risk Factors * | Beta Coefficient | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.032 | (−0.072, 0.008) | 0.257 |

| BMI in first trimester | −0.124 | (−0.194, −0.054) | 0.019 |

| Unmarried civil status | −0.323 | (−0.519, −0.127) | 0.045 |

| Previous abortion | −0.451 | (−0.697, −0.205) | 0.012 |

| Irregular menstrual cycle | −0.384 | (−0.598, −0.170) | 0.026 |

| Rural living area | −0.278 | (−0.442, −0.114) | 0.034 |

| BDI score in first trimester | −0.045 | (−0.075, −0.015) | 0.004 |

| Unplanned pregnancy | −0.054 | (−0.086, −0.022) | 0.095 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daniluc, R.-I.; Craina, M.; Thakur, B.R.; Prodan, M.; Bratu, M.L.; Daescu, A.-M.C.; Puenea, G.; Niculescu, B.; Negrean, R.A. Comparing Relationship Satisfaction and Body-Image-Related Quality of Life in Pregnant Women with Planned and Unplanned Pregnancies. Diseases 2024, 12, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12060109

Daniluc R-I, Craina M, Thakur BR, Prodan M, Bratu ML, Daescu A-MC, Puenea G, Niculescu B, Negrean RA. Comparing Relationship Satisfaction and Body-Image-Related Quality of Life in Pregnant Women with Planned and Unplanned Pregnancies. Diseases. 2024; 12(6):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12060109

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaniluc, Razvan-Ionut, Marius Craina, Barkha Rani Thakur, Mihaela Prodan, Melania Lavinia Bratu, Ana-Maria Cristina Daescu, George Puenea, Bogdan Niculescu, and Rodica Anamaria Negrean. 2024. "Comparing Relationship Satisfaction and Body-Image-Related Quality of Life in Pregnant Women with Planned and Unplanned Pregnancies" Diseases 12, no. 6: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12060109

APA StyleDaniluc, R.-I., Craina, M., Thakur, B. R., Prodan, M., Bratu, M. L., Daescu, A.-M. C., Puenea, G., Niculescu, B., & Negrean, R. A. (2024). Comparing Relationship Satisfaction and Body-Image-Related Quality of Life in Pregnant Women with Planned and Unplanned Pregnancies. Diseases, 12(6), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12060109