Abstract

Background/Objectives: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is emerging as a significant GI sequela post-COVID-19 infection. This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence and incidence of SIBO post-COVID-19 infection across different age groups and to identify associated risk factors in a global cohort. Methods: A retrospective study utilized the TriNetX database and included adult patients (≥18 years) diagnosed with SIBO following COVID-19 infection (1 January 2022–30 May 2024). A propensity score matching (1:1) was used to adjust for demographics and SIBO risk factors. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis assessed the SIBO incidence within 12 months. Results: Among 1,660,092 COVID-19 patients and 42,322,017 controls, SIBO was diagnosed in 353 COVID-19 patients without hydrogen breath tests (BT) and 78 with BT, compared to 3368 controls without BT and 871 with BT. Age-specific analysis demonstrated a clear, progressive increase in the SIBO incidence, becoming distinctly significant by 6 months and highest at 12 months post-infection. The highest risks were noted in ages 60–69 (0.011% vs. 0.004%, OR 2.6, p = 0.0003) and 70–79 (0.011% vs. 0.005%, OR 2.0, p = 0.0004), with younger age groups (30–49 years) also showing significantly increased risks. The medication analysis revealed strong associations with chronic opioid, proton pump inhibitor, and antidiarrheal medication. Conclusions: COVID-19 significantly increased the risk of SIBO, particularly within the first 12 months post-infection, across various age groups and, notably, in association with certain chronic medications. Clinical vigilance and targeted management strategies are recommended to mitigate long-term GI consequences.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with a group of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, a loss of appetite, acid reflux, and esophageal disorders during and after the acute phase of COVID-19 infection [1,2,3]. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is not a common GI symptom caused by COVID-19 infection and there are only a handful of reports on new-onset SIBO cases post-infection [4,5,6]. Possible mechanisms include gut microbiota disturbance and renin–angiotensin system dysfunction. Previous studies have shown fecal microbiome changes up to 30 days post-COVID-19 infection [7,8,9].

The COVID-19 virus is believed to bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor on the alveolar epithelial cells, leading to lung infection. It is hypothesized that the virus also binds to the ACE-2 receptor in the small intestine epithelia cells, causing an imbalance in the gut microbiota [10,11,12]. Furthermore, a population-based study showed gastrointestinal motility disorders lasting up to one year post-COVID-19 infection, which may contribute to the development of SIBO [13].

SIBO is caused by an excessive bacteria presence in the small intestine and is associated with a range of symptoms, including bloating, abdominal distension, abdominal pain/discomfort, diarrhea, fatigue, and weakness [14]. Patients with SIBO can develop severe malnutrition, vitamin B12 deficiency, anemia, osteoporosis, and steatorrhea, which can lead to more severe adverse outcomes or the worsening of comorbidities without timely treatment [14]. Breath tests (BT) of lactulose and glucose are recommended for SIBO diagnosis in symptomatic patients [15]. Antibiotic treatment is warranted upon diagnosis and can reduce the recurrence of SIBO [16].

Given the lack of data on the prevalence and incidence of SIBO following COVID-19 infection in large population-based cohorts, the aim of this study was to determine whether the risk of SIBO development increased after COVID-19 infection. The correlations between clinical characteristics, comorbidities, medications, and SIBO prevalence, as well as the percentage of SIBO cases diagnosed with BT, were assessed as secondary outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective study was conducted with the TriNetX database (Cambridge, MA, USA), a de-identified, multicenter global database that provides anonymized real-world data. It encompasses over 275 million patient records from 152 healthcare organizations across 21 countries [17]. The platform enables patient-level analysis while preserving anonymity—any data points involving 10 or fewer individuals are not displayed, ensuring compliance with the strict privacy standards. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland and MetroHealth Medical Center classified studies using TriNetX as exempt from the IRB review, as the data meet the de-identification criteria outlined in Section §164.514 (a) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. This study was reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for cohort studies [18].

2.1. Patient Selection

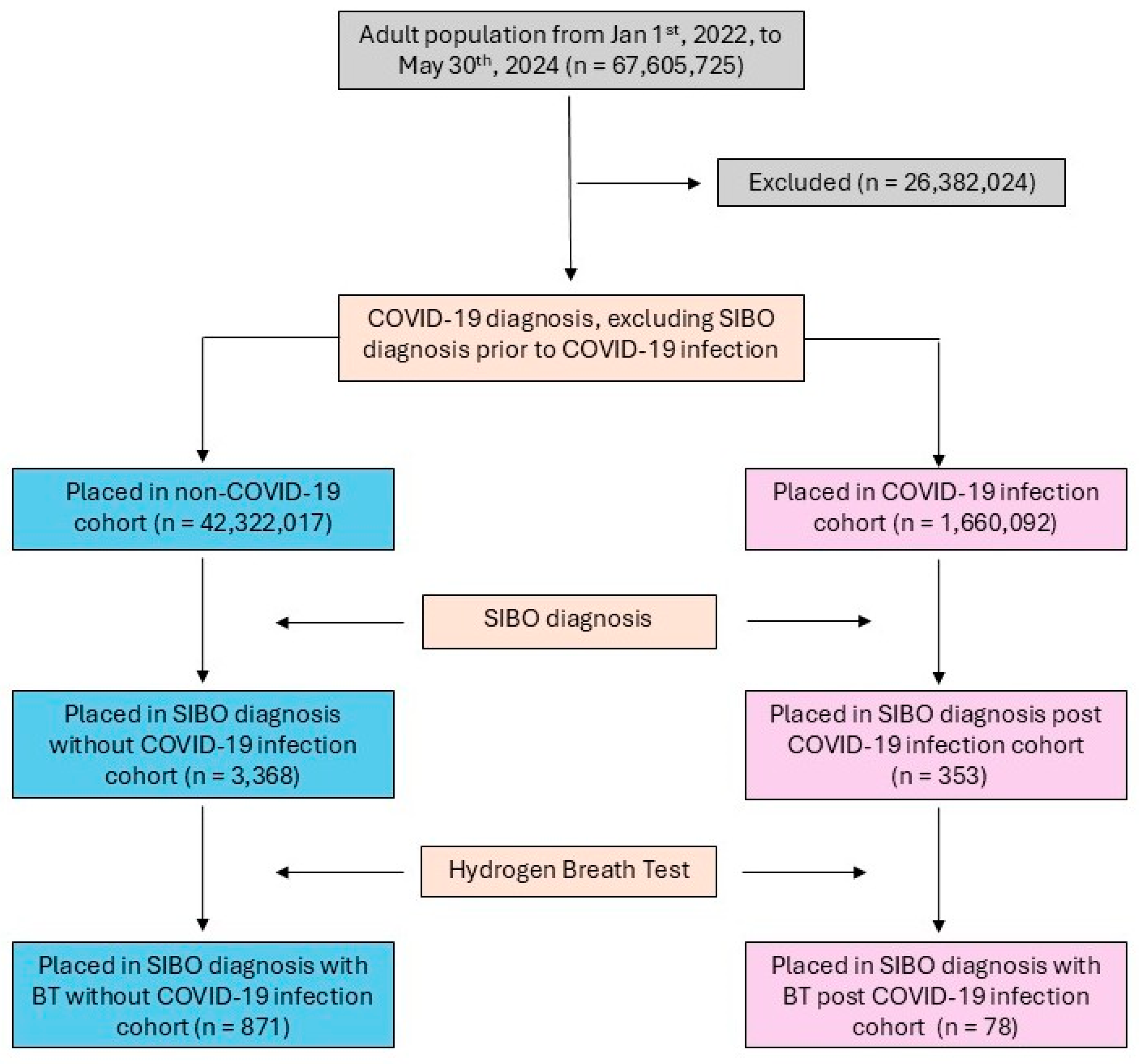

Adult patients aged 18 years or older from 1 January 2022 to 30 May 2024 were identified using the TriNetX database. The time frame was selected to align with the global adoption of SIBO diagnostic coding and a 12-month follow-up period. The COVID-19 cohort included patients diagnosed with COVID-19 or those with a recorded positive COVID-19 test result. The control cohort excluded patients with any documented COVID-19 diagnosis or positive test result (Figure 1). Both cohorts were subject to the same exclusion criteria, including a history of major GI or abdominal surgeries (e.g., bariatric surgery and cesarean sections), connective tissue disorders (e.g., amyloidosis and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome), Sjögren’s syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, inflammatory bowel diseases (e.g., ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease), and other GI conditions such as cystic fibrosis and esophageal dyskinesia (Appendix A Table A1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of COVID-19/control cohorts’ selection flow.

2.2. Query Validation

Queries were validated by performing an unmatched analysis on patients diagnosed with SIBO, with or without COVID-19 infection from 1 January 2022 to 30 May 2024, to align with the global adoption of the SIBO diagnostic coding time and 12-month follow-up period. From the cohorts of patients with SIBO, we further identified the number of patients who underwent hydrogen BT.

2.3. Covariates and Matching

Confounding factors that could influence the risk of SIBO were identified. One-to-one propensity score matching (PSM) was performed using these factors, which included demographic variables such as the age at index event, sex, ethnicity, race, body mass index (BMI), end-stage renal disease, and medication including opioids, diphenoxylate, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

2.4. Propensity-Matched Study Outcomes

The outcome of this study was the development of SIBO. This outcome was analyzed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-COVID-19 infection. The two cohorts were further stratified with the age groups: 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years. The risk of SIBO development was compared among all age groups at each of the four follow-up time points.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the TriNetX platform [17]. Outcomes were summarized using means, standard deviations (SD), and percentages, as appropriate. PSM was performed in a 1:1 fashion using relevant covariates via a greedy nearest neighbor algorithm with a caliper width of 0.1. Matched cohorts were considered well-balanced based on baseline characteristics. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was conducted within the TriNetX platform. Patients were followed until the occurrence of a SIBO outcome, their last recorded clinical encounter, or death—whichever occurred first. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the TriNetX analytics platform to compare SIBO outcomes between cohorts. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value less than 0.05. The figure was generated in Microsoft PowerPoint (Redmond, WA, USA) version 2505.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Prevalence and Incidence of SIBO

A total of 1,660,092 COVID-19 patients and 42,322,017 controls were analyzed. SIBO was diagnosed in 353 (0.021%) COVID-19 patients without hydrogen BT and 78 (0.005%) patients confirmed by BT, compared to 3368 (0.008%) controls without BT and 871 (0.002%) with BT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and comorbidities of all study populations and cohorts of SIBO patients with or without COVID-19 infection.

3.2. Demographic Characteristics

COVID-19 patients diagnosed with SIBO were significantly older (51.4 ± 17.3 years vs. 47.3 ± 17.5 years, p < 0.001) and had a higher BMI (26.5 ± 6.0 kg/m2 vs. 25.6 ± 5.8 kg/m2, p = 0.008) compared to controls. Female patients constituted approximately 75% in both groups, without a significant difference (p = 0.855). The ethnic composition showed that COVID-19 patients with SIBO had slightly fewer Hispanic or Latino patients (4.8% vs. 6.3%, p = 0.071) and more White individuals (82.4% vs. 75.8%, p = 0.174). Statistically significant differences were observed among Black or African American (6.5% vs. 5.9%, p = 0.030) and Asian patients (2.8% vs. 3.6%, p = 0.048, Table 1).

3.3. Age-Specific Incidence of SIBO

The incidence of SIBO showed a progressive and time-dependent increase following COVID-19 infection. While no significant differences between the COVID-19 and control cohorts were observed at 1-month post-infection, a trend toward higher risk began to emerge at 3 months, which was particularly noticeable in the 70–79 years age group (p = 0.012). By 6 months, this elevated risk became more apparent and statistically significant across multiple age groups (ages 30–69; all p < 0.05, Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of SIBO within 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after COVID-19 infection versus without COVID-19 infection in different age groups.

At the 12-month follow-up, the increased risk was most pronounced and statistically significant across all age groups studied. Specifically, older adults (ages 60–69 and 70–79) exhibited the highest incidences of SIBO (0.011% in COVID-19 patients compared to 0.004–0.005% in controls; OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.3–5.4, p = 0.0003, and OR 2.0, 95% CI 0.94–4.27, p = 0.0004, respectively; Table 3).

Table 3.

SIBO cases within 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after COVID-19 infection versus without COVID-19 infection post-PSM in different age groups.

Significant elevations were also evident in younger cohorts: ages 30–39 years (0.009% vs. 0.003%; OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.3–5.8, p = 0.002) and 40–49 years (0.009% vs. 0.004%; OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.1–5.0, p < 0.0001; Table 3). Additionally, in patients aged ≥ 80 years, a noteworthy incidence of 0.007% was observed, whereas no cases were reported in the matched control group (p = 0.021).

3.4. Medication Use and Associated Risks

Significant medication use associated with an increased risk of SIBO among COVID-19 patients included chronic opioid use (3% vs. 0.4%, p < 0.001) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) such as pantoprazole (18% vs. 12%, p = 0.002) and omeprazole (32% vs. 18%, p < 0.001). Antidiarrheal medications were also associated with an increased risk, including loperamide (3% vs. 1%, p < 0.001) and diphenoxylate (3% vs. 0%, p < 0.001; Table 4).

Table 4.

Medication use and associated risks of SIBO among population with or without COVID-19 infection.

4. Discussion

COVID-19 has been widely associated with GI symptoms, including bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and discomfort, as well as significant long-term disruptions to the gut microbiome [1,11,13]. Although isolated case reports have previously identified instances of SIBO following COVID-19 [4,5,6,19], our study is the first to quantitatively analyze the incidence of SIBO using extensive global real-world data. Our findings indicate a notable, time-dependent increase in the risk of SIBO, becoming particularly evident by 6 months and peaking at 12 months post-infection. This comprehensive analysis substantially advances our understanding of post-COVID-19 gastrointestinal outcomes, highlighting both age-specific vulnerabilities and medication-related risk factors.

The development of SIBO typically occurs due to disruptions in the normal gut bacterial equilibrium, often resulting from diminished gastric acid secretion or impaired intestinal motility [14]. COVID-19 patients exhibit sustained alterations in their fecal microbiome for up to 30 days post-infection [7,8,9]. Large-scale analyses, such as those based on the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs database, have similarly highlighted persistent GI complications, including motility disorders, lasting up to one year post-infection [13]. Supporting studies have further documented similar gastrointestinal disruptions at shorter intervals, including 90 days and 6 months post-infection [3,20]. These previous observations closely align with our findings, which demonstrate a clear progressive increase in SIBO incidence, likely attributable to microbiome imbalances and motility dysfunctions. A previous study involving 495 adult hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Italy indicated differences in the age, comorbidities, and hospital stay length between sexes [21]. Our data did not demonstrate gender differences in these aspects, potentially due to the difference in size, the geography of the study population, and the fact that we included both the inpatient and outpatient population.

Prior studies have reported a SIBO prevalence ranging broadly from 2.5% to 22% across various populations [22], with significantly higher rates, up to 93.8%, observed among patients with post-COVID-19 irritable bowel syndrome [23]. Recognizing the challenge of precisely attributing the SIBO etiology, our study applied rigorous exclusion criteria and PSM to minimize confounding factors. Notably, the SIBO prevalence is reported to be particularly high, up to 52.5%, among individuals aged over 75, roughly twice the prevalence in younger populations, highlighting potential under-diagnosis in older demographics. Our findings reinforce this observation, demonstrating a significantly increased SIBO risk among individuals aged over 80 within 12 months post-COVID-19, compared to matched controls. Given that untreated SIBO can lead to severe nutritional and metabolic complications, including malnutrition, vitamin B12 deficiency, anemia, osteoporosis, and steatorrhea [14], timely diagnosis and intervention are crucial. Moreover, while older adults (60–79 years) displayed the highest incidence, the significant SIBO risk identified among younger individuals (30–49 years) underscores the necessity of broad clinical vigilance across all age groups.

In our study, the majority of SIBO diagnoses among COVID-19 patients were based on clinical presentations rather than BT confirmations, reflecting limitations in current diagnostic practices. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines recommend BT primarily for symptomatic patients with IBS, suspected motility disorders, or a history of luminal abdominal surgery, and advise against its routine use in asymptomatic patients on PPIs due to limited evidence [15]. BT’s diagnostic utility remains controversial due to relatively low sensitivity (42% for lactulose and 54.5% for glucose) and potential false positives driven by colonic fermentation rather than true SIBO [24,25]. The significant increase in the post-COVID-19 SIBO incidence observed in our study emphasizes the critical need for enhanced clinical vigilance, improved diagnostic methodologies, and proactive therapeutic interventions.

Another significant observation was the increased SIBO risk associated with chronic opioid, diphenoxylate, and PPI usage. Both opioids and diphenoxylate, acting as µ receptor agonists, can significantly slow GI transit and disrupt the gut microbiota composition [26,27]. Similarly, long-term PPI use increases the risk of SIBO by reducing gastric acid secretion, a relationship consistently demonstrated in multiple meta-analyses [28,29]. Our findings, which align closely with these previously reported associations, reinforce the need for the cautious prescribing and optimized clinical management of PPIs and antiperistaltic agents to minimize the potential risk of SIBO.

There are several limitations of this study. As a retrospective cohort study, it carries limitations such as variability in the data quality and the researchers’ lack of control over how the data were originally collected. Additionally, the potential misdiagnosis and incomplete electronic health records (EHR) can interfere with the result accuracy, especially among countries/areas utilizing physical paper format medical records. Another limitation of utilizing this database is that the large study population size may lead to the overestimation of the statistical significance. The under-detection of COVID-19 is another limitation, especially among asymptomatic patients or those with mild upper respiratory symptoms. This concern also applies to the under-detection of SIBO, where patients with a younger age or mild symptoms might not seek medical care. SIBO cases identified in both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 cohorts were less than 10 at multiple follow-up times, which could be caused by the under-detection of COVID-19 and SIBO cases. Furthermore, we could not collect the information on whether the study population consumed probiotic or other types of supplement that might alter their gut microbiota environment. To further validate and extend our findings, prospective studies are essential. Prospective designs would ensure higher data accuracy and quality control. The further refinement of diagnostic methodologies, such as revising hydrogen BT cutoff thresholds to enhance sensitivity [30], and investigations into antibiotic management strategies for SIBO are also promising avenues for future research. Understanding the mechanisms underlying COVID-19′s impact on SIBO development would further enhance the clinical relevance and applicability of our findings.

5. Conclusions

This study provides novel and robust evidence of a significant and progressive increase in the SIBO incidence following COVID-19 infection using a global, multicenter, real-world dataset. The elevation of the SIBO risk was most pronounced by the 12-month follow-up, prominently affecting older adults aged 60–79 years, with notable implications for younger populations as well. These findings highlight the importance of the increased clinical awareness, early diagnosis, and proactive management of SIBO in patients recovering from COVID-19, particularly among elderly individuals and those utilizing chronic medications.

Author Contributions

Y.S.: validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, and prepared the original draft. T.H.K. and B.D.L.: data interpretation, validation and formal analysis, and data acquisition. L.L.D.Z., T.B. and X.H.: conceptualization, data interpretation, and review and editing. G.S. and L.T.: conceptualization, supervision, and review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All raw output from data from TriNetX are available by contacting Yilin Song or Gengqing Song.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SIBO | Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| BT | Breath test |

| PSM | Propensity score matching |

| PPI | Proton pump inhibitor |

| ACE-2 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Exclusion criteria of both COVID-19 and control cohorts.

Table A1.

Exclusion criteria of both COVID-19 and control cohorts.

| Appendix 1—Exclusion Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007215 | Incision Procedures on the Esophagus | |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007219 | Excision Procedures on the Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007298 | Repair Procedures on the Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007341 | Other Procedures on the Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007345 | Incision Procedures on the Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007352 | Excision Procedures on the Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007372 | Laparoscopic Procedures on the Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43279 | Laparoscopy, surgical, esophagomyotomy (Heller type), with fundoplasty, when performed |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007392 | Other Procedures on the Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43283 | Laparoscopy, surgical, esophageal lengthening procedure (e.g., Collis gastroplasty or wedge gastroplasty) (list separately in addition to code for primary procedure) |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1020218 | Laparoscopy, surgical, repair of paraesophageal hernia, includes fundoplasty, when performed |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43285 | Removal of esophageal sphincter augmentation device |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1020218 | Laparoscopy, surgical, repair of paraesophageal hernia, includes fundoplasty, when performed |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43285 | Removal of esophageal sphincter augmentation device |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43286 | Esophagectomy, total or near total, with laparoscopic mobilization of the abdominal and mediastinal esophagus and proximal gastrectomy, with laparoscopic pyloric drainage procedure if performed, with open cervical pharyngogastrostomy or esophagogastrostomy (i.e., laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy) |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43287 | Esophagectomy, distal two-thirds, with laparoscopic mobilization of the abdominal and lower mediastinal esophagus and proximal gastrectomy, with laparoscopic pyloric drainage procedure if performed, with separate thoracoscopic mobilization of the middle and upper mediastinal esophagus and thoracic esophagogastrostomy (i.e., laparoscopic thoracoscopic esophagectomy, Ivor Lewis esophagectomy) |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43288 | Esophagectomy, total or near total, with thoracoscopic mobilization of the upper, middle, and lower mediastinal esophagus, with separate laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy, with laparoscopic pyloric drainage procedure if performed, with open cervical pharyngogastrostomy or esophagogastrostomy (i.e., thoracoscopic, laparoscopic, and cervical incision esophagectomy, McKeown esophagectomy, tri-incisional esophagectomy) |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DV1 | Gastrointestinal System/Restriction/Esophagus, Upper |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DV2 | Gastrointestinal System/Restriction/Esophagus, Middle |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43289 | Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DV6 | Gastrointestinal System/Restriction/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DV5 | Gastrointestinal System/Restriction/Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DV7 | Gastrointestinal System/Restriction/Stomach, Pylorus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D11 | Gastrointestinal System/Bypass/Esophagus, Upper |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D76 | Gastrointestinal System/Dilation/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D77 | Gastrointestinal System/Dilation/Stomach, Pylorus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D51 | Gastrointestinal System/Destruction/Esophagus, Upper |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D52 | Gastrointestinal System/Destruction/Esophagus, Middle |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D53 | Gastrointestinal System/Destruction/Esophagus, Lower |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D54 | Gastrointestinal System/Destruction/Esophagogastric Junction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D55 | Gastrointestinal System/Destruction/Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D56 | Gastrointestinal System/Destruction/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D57 | Gastrointestinal System/Destruction/Stomach, Pylorus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D84 | Gastrointestinal System/Division/Esophagogastric Junction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D87 | Gastrointestinal System/Division/Stomach, Pylorus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DB1 | Gastrointestinal System/Excision/Esophagus, Upper |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DB6 | Gastrointestinal System/Excision/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DB5 | Gastrointestinal System/Excision/Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DB2 | Gastrointestinal System/Excision/Esophagus, Middle |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DB3 | Gastrointestinal System/Excision/Esophagus, Lower |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DB4 | Gastrointestinal System/Excision/Esophagogastric Junction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DB7 | Gastrointestinal System/Excision/Stomach, Pylorus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DC1 | Gastrointestinal System/Extirpation/Esophagus, Upper |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DC2 | Gastrointestinal System/Extirpation/Esophagus, Middle |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DC3 | Gastrointestinal System/Extirpation/Esophagus, Lower |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DC4 | Gastrointestinal System/Extirpation/Esophagogastric Junction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DC5 | Gastrointestinal System/Extirpation/Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DC6 | Gastrointestinal System/Extirpation/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DC7 | Gastrointestinal System/Extirpation/Stomach, Pylorus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DD | Extraction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DD1 | Gastrointestinal System/Extraction/Esophagus, Upper |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DD2 | Gastrointestinal System/Extraction/Esophagus, Middle |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DD3 | Gastrointestinal System/Extraction/Esophagus, Lower |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DD4 | Gastrointestinal System/Extraction/Esophagogastric Junction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DD5 | Gastrointestinal System/Extraction/Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DD6 | Gastrointestinal System/Extraction/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DF5 | Gastrointestinal System/Fragmentation/Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DD7 | Gastrointestinal System/Extraction/Stomach, Pylorus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DF6 | Gastrointestinal System/Fragmentation/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DL1 | Gastrointestinal System/Occlusion/Esophagus, Upper |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DL2 | Gastrointestinal System/Occlusion/Esophagus, Middle |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DL3 | Gastrointestinal System/Occlusion/Esophagus, Lower |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DL4 | Gastrointestinal System/Occlusion/Esophagogastric Junction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DL5 | Gastrointestinal System/Occlusion/Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DL6 | Gastrointestinal System/Occlusion/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DL7 | Gastrointestinal System/Occlusion/Stomach, Pylorus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DT1 | Gastrointestinal System/Resection/Esophagus, Upper |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DT2 | Gastrointestinal System/Resection/Esophagus, Middle |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DT5 | Gastrointestinal System/Resection/Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DT4 | Gastrointestinal System/Resection/Esophagogastric Junction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DT3 | Gastrointestinal System/Resection/Esophagus, Lower |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DT6 | Gastrointestinal System/Resection/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DT7 | Gastrointestinal System/Resection/Stomach, Pylorus |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:K22.4 | Dyskinesia of esophagus |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:M34 | Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma] |

| or | treatment | TNX:1001 | Radiation |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:L93 | Lupus erythematosus |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:M35.0 | Sjögren syndrome |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43284 | Laparoscopy, surgical, esophageal sphincter augmentation procedure, placement of sphincter augmentation device (i.e., magnetic band), including cruroplasty when performed |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D16 | Gastrointestinal System/Bypass/Stomach |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DV4 | Gastrointestinal System/Restriction/Esophagogastric Junction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007335 | Manipulation Procedures on the Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:43280 | Laparoscopy, surgical, esophagogastric fundoplasty (e.g., Nissen, Toupet procedures) |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007385 | Bariatric Surgery Procedures |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D74 | Gastrointestinal System/Dilation/Esophagogastric Junction |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D71 | Gastrointestinal System/Dilation/Esophagus, Upper |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0DV3 | Gastrointestinal System/Restriction/Esophagus, Lower |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D72 | Gastrointestinal System/Dilation/Esophagus, Middle |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D75 | Gastrointestinal System/Dilation/Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD10PCS:0D73 | Gastrointestinal System/Dilation/Esophagus, Lower |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:Z90.49 | Acquired absence of other specified parts of digestive tract |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007463 | Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy |

| or | procedure | UMLS:SNOMED:4558008 | Anterior resection of rectum |

| or | procedure | UMLS:ICD9CM:46.2 | Ileostomy |

| or | procedure | UMLS:SNOMED:80146002 | Appendectomy |

| or | procedure | UMLS:SNOMED:11466000 | Cesarean section |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:Q79.6 | Ehlers–Danlos syndromes |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:K56.5 | Intestinal adhesions [bands] with obstruction (post-infection) |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:G95 | Other and unspecified diseases of spinal cord |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:G20 | Parkinson’s disease |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:K51 | Ulcerative colitis |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:K52.8 | Other specified non-infective gastroenteritis and colitis |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:K50 | Crohn’s disease [regional enteritis] |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:E85 | Amyloidosis |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:G35 | Multiple sclerosis |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:M34 | Systemic sclerosis [scleroderma] |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:K90.83 | Intestinal failure |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:K63.2 | Fistula of intestine |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:K56.6 | Other and unspecified intestinal obstruction |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:E84 | Cystic fibrosis |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007692 | Other Procedures on the Colon and Rectum |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007687 | Manipulation Procedures on the Rectum |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007671 | Repair Procedures on the Rectum |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007663 | Laparoscopic Procedures on the Rectum |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007620 | Destruction Procedures on the Rectum |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007596 | Excision Procedures on the Rectum |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007592 | Incision Procedures on the Rectum |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:47715 | Excision of choledochal cyst |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:47570 | Laparoscopy, surgical; cholecystoenterostomy |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:47701 | Portoenterostomy (e.g., Kasai procedure) |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:47700 | Exploration for congenital atresia of bile ducts, without repair, with or without liver biopsy, with or without cholangiography |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007887 | Excision of bile duct tumor, with or without primary repair of bile duct |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:47579 | Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, biliary tract |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1018154 | Other Procedures on the Biliary Tract |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007892 | Repair Procedures on the Biliary Tract |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007854 | Introduction Procedures on the Biliary Tract |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007846 | Incision Procedures on the Biliary Tract |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007341 | Other Procedures on the Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007295 | Laparoscopic Procedures on the Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007298 | Repair Procedures on the Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007219 | Excision Procedures on the Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007215 | Incision Procedures on the Esophagus |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007952 | Surgical Procedures on the Abdomen, Peritoneum, and Omentum |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007908 | Surgical Procedures on the Pancreas |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007795 | Surgical Procedures on the Liver |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007422 | Surgical Procedures on the Intestines (Except Rectum) |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007344 | Surgical Procedures on the Stomach |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:K52.9 | Non-infective gastroenteritis and colitis, unspecified |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007570 | Surgical Procedures on Meckel’s Diverticulum and the Mesentery |

| or | procedure | UMLS:CPT:1007695 | Surgical Procedures on the Anus |

| or | diagnosis | UMLS:ICD10CM:Z87.19 | Personal history of other diseases of the digestive system |

References

- Rokkas, T. Gastrointestinal involvement in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2020, 33, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Xie, Y.; Bowe, B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 594, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Shen, L.; Zhu, L.; Liang, Y.; Lin, X.; Jiao, N.; Cheng, S.; Huang, Y.; et al. Gastrointestinal sequelae 90 days after discharge for COVID-19. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 344–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, B.; Ansari, M.; Mohamed, A.; Dankyi, B. S3484 Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth After COVID-19 Infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, e2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Mathew, R.; Jadeja, S.; Schey, R.; Masri, G. S3006 Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth After COVID-19 Infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, S1243–S1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changela, S.; Ashraf, S.; Lu, J.Y.; Duong, K.E.; Henry, S.; Wang, S.H.; Duong, T.Q. New-onset gastrointestinal disorders in COVID-19 patients 3.5 years post-infection in the inner-city population in the Bronx. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, K.S.; Singh, Y.; Hassan Almalki, W.; Rawat, S.; Afzal, O.; Alfawaz Altamimi, A.S.; Kazmi, I.; Al-Abbasi, F.A.; Alzarea, S.I.; Singh, S.K.; et al. Gut Microbiota Disruption in COVID-19 or Post-COVID Illness Association with severity biomarkers: A Possible Role of Pre/Pro-biotics in manipulating microflora. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 358, 109898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, Y.K.; Zuo, T.; Lui, G.C.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Li, A.Y.; Chung, A.C.; Cheung, C.P.; Tso, E.Y.; Fung, K.S.; et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021, 70, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G.C.Y.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Li, A.Y.L.; Zhan, H.; Wan, Y.; Chung, A.C.K.; Cheung, C.P.; Chen, N.; et al. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 944–955 e948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, K.; Perez, L.G.; Costa, L.B.; Cordeiro, T.M.; Palmeira, V.A.; Ribeiro, V.T.; Simoes, E.S.A.C. Covid-19: The renin-angiotensin system imbalance hypothesis. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, D.; Mohanty, A. Gut microbiota and Covid-19-possible link and implications. Virus Res. 2020, 285, 198018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, K.; Koper, M.; Ufnal, M. Gut microbiota and renin-angiotensin system: A complex interplay at local and systemic levels. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2021, 321, G355–G366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Xie, Y.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term gastrointestinal outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dukowicz, A.C.; Lacy, B.E.; Levine, G.M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A comprehensive review. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 3, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, M.; Saad, R.J.; Long, M.D.; Rao, S.S.C. ACG Clinical Guideline: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Sachdeva, S.; Ghoshal, U.; Misra, A.; Puri, A.S.; Pratap, N.; Shah, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Gwee, K.A.; Tan, V.P.Y.; et al. Asian-Pacific consensus on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in gastrointestinal disorders: An initiative of the Indian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 41, 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TriNetX. Available online: https://trinetx.com/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisuradze, M.; Tavartkiladze, A.; Simonia, G.; Revazishvili, P.; Nozadze, P.; Lou, R.; Mamukashvili, G.; Zumbadze, G.; Japaridze, T.; Potskhoraia, T.; et al. Low Melatonin and Post-COVID Syndrome: Unveiling SIBO as a Potential Pre-Cancerous Condition in the Post-Pandemic Era. J. Cancer Res. 2024, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golla, R.; Vuyyuru, S.; Kante, B.; Kumar, P.; Thomas, D.M.; Makharia, G.; Kedia, S.; Ahuja, V. Long-term Gastrointestinal Sequelae Following COVID-19: A Prospective Follow-up Cohort Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; Fabbri, N.; Bella, A.; Bonsi, B.; Parini, S.; Rocchi, C.; Giaccari, S.; Gavioli, M.; Passaro, A.; Feo, C.V. COVID-19 inpatients with gastrointestinal onset: Sex and care needs’ differences in the district of Ferrara, Italy. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzydlo-Radomanska, B.; Cukrowska, B. How to Recognize and Treat Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efremova, I.; Maslennikov, R.; Poluektova, E.; Vasilieva, E.; Zharikov, Y.; Suslov, A.; Letyagina, Y.; Kozlov, E.; Levshina, A.; Ivashkin, V. Epidemiology of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 3400–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losurdo, G.; Leandro, G.; Ierardi, E.; Perri, F.; Barone, M.; Principi, M.; Leo, A.D. Breath Tests for the Non-invasive Diagnosis of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020, 26, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Rezaie, A. Pros and Cons of Breath Testing for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 19, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zadori, Z.S.; Kiraly, K.; Al-Khrasani, M.; Gyires, K. Interactions between NSAIDs, opioids and the gut microbiota—Future perspectives in the management of inflammation and pain. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 241, 108327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Wylie, W.P. Diphenoxylate and Atropine. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559300 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Su, T.; Lai, S.; Lee, A.; He, X.; Chen, S. Meta-analysis: Proton pump inhibitors moderately increase the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.K.; Chan, W.W. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.R.; Chey, W.D.; Watts, L.; Armstrong, M.; Collins, K.; Lee, A.A.; Dupati, A.; Menees, S.; Saad, R.J.; Harer, K.; et al. How the North American Consensus Protocol Affects the Performance of Glucose Breath Testing for Bacterial Overgrowth Versus a Traditional Method. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).