Early Maladaptive Schemas and Their Impact on Parenting: Do Dysfunctional Schemas Pass Generationally?—A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Current Review

2. Methodology

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Methodological Quality Assessment

2.4. Main Outcomes

2.5. Data Extraction (Selection and Coding)

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Included Studies

3.2. Study’s Characteristics

3.3. Sample’s Characteristics

3.4. Measurement Characteristics

3.5. Main Findings

3.5.1. Characteristics of the Relationship between Parents’ EMSs and Their Children’s EMSs

3.5.2. The Impact of EMSs of Parent on Parenting

4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions: Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, B.A. Healing Factors of Psychiatry in Light of Attachment Theory. Am. J. Psychother. 1983, 37, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnicott, D.W.; Donald, W. The Child, the Family, and the Outside World; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Reading, MA, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-201-16517-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gajos, J.M.; Miller, C.R.; Leban, L.; Cropsey, K.L. Adverse childhood experiences and adolescent mental health: Understanding the roles of gender and teenage risk and protective factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 314, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, K.R.; Townsend, M.L.; Grenyer, B.F.S. Parenting and personality disorder: An overview and meta-synthesis of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.E. Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schema-Focused Approach, 3rd ed.; Professional Resource Press/Professional Resource Exchange: Sarasota, FL, USA, 1999; p. x83. ISBN 978-1-56887-047-2. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.E.; Klosko, J.S.; Weishaar, M.E. Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 7. ISBN 978-1-59385-372-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, B.; Lockwood, G.; Young, J.E. A new look at the schema therapy model: Organization and role of early maladaptive schemas. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2017, 47, 328–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Sheridan, M. Beyond Cumulative Risk: A Dimensional Approach to Childhood Adversity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 25, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, P.D.; Bishop, A.; Younan, R. Adverse childhood experiences and early maladaptive schemas in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2020, 28, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, T.; Younan, R.; Pilkington, P.D. Adolescent maladaptive schemas and childhood abuse and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2022, 29, 1159–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, M.W.; Chapman, A.; Cellucci, T. Schemas and borderline personality disorder symptoms in incarcerated women. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2009, 40, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimm, J.C. Mediation of early maladaptive schemas between perceptions of parental rearing style and personality disorder symptoms. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2010, 41, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Weijer, S.G.A.; Bijleveld, C.C.J.H.; Blokland, A.A.J. The Intergenerational Transmission of Violent Offending. J. Fam. Violence 2014, 29, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhdir, M.P.A.; Nathwani, A.A.; Ali, N.A.; Farooq, S.; Azam, S.I.; Khaliq, A.; Kadir, M.M. Intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment: Predictors of child emotional maltreatment among 11 to 17 years old children residing in communities of Karachi, Pakistan. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 91, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, J.D.; Kotake, C.; Fauth, R.; Easterbrooks, M.A. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: Do maltreatment type, perpetrator, and substantiation status matter? Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 63, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigan, S.; Cyr, C.; Eirich, R.; Fearon, R.M.P.; Ly, A.; Rash, C.; Poole, J.C.; Alink, L.R.A. Testing the cycle of maltreatment hypothesis: Meta-analytic evidence of the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotto, C.R.; Altafim, E.R.P.; Linhares, M.B.M. Maternal History of Childhood Adversities and Later Negative Parenting: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2021, 1, 15248380211036076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, H.; Lobbestael, J.; Candel, I.; Batink, T. Early maladaptive schemas and their relation to personality disorders: A correlational examination in a clinical population. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2020, 27, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Reid, C.; Chan, S.W.Y. A meta-analysis of the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1233–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, E.; Wen, A.; Dobson, K.S.; Noorbala, A.A.; Mohammadi, A.; Farahmand, Z. Early maladaptive schemas in depression and somatization disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 235, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, A.; Cason, L.; Huckstepp, T.; Stallman, H.; Kannis-Dymand, L.; Millear, P.; Mason, J.; Wood, A.; Allen, A. Early maladaptive schemas in eating disorders: A systematic review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2022, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, N.; van Passel, B.; Krans, J. The effectiveness of schema therapy for patients with anxiety disorders, OCD, or PTSD: A systematic review and research agenda. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 61, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Harvey, K.; Baranowska, M.; O’Brien, D.; Smith, L.; Creswell, C. What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 623–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Pereson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Modesti, P.A.; Reboldi, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Agyemang, C.; Remuzzi, G.; Rapi, S.; Perruolo, E.; Parati, G. ESH Working Group on CV Risk in Low Resource Settings Panethnic Differences in Blood Pressure in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adibsereshki, N.; Rafi, M.A.; Aval, M.H.; Tahan, H. Looking into some of the risk factors of mental health: The mediating role of maladaptive schemas in mothers’ parenting style and child anxiety disorders. J. Public Ment. Health 2018, 17, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, Z.G.; Schneider, S.; Hudson, J.L.; Habibi, M.; Pooravari, M.; Heidari, Z.H. Early Maladaptive Schemas as Predictors of Child Anxiety: The Role of Child and Mother Schemas. Int. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2014, 1, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.C.; Anderson, S.; Stuart, G.L. An Examination of Early Maladaptive Schemas among Substance Use Treatment Seekers and their Parents. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2012, 34, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mącik, D.; Chodkiewicz, J.; Bielicka, D. Trans-generational transfer of early maladaptive schemas—A preliminary study performed on a non-clinical group. Curr. Issues Pers. Psychol. 2016, 4, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklósi, M.; Szabó, M.; Simon, L. The Role of Mindfulness in the Relationship between Perceived Parenting, Early Maladaptive Schemata and Parental Sense of Competence. Mindfulness 2016, 8, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundag, J.; Zens, C.; Ascone, L.; Thome, S.; Lincoln, T.M. Are Schemas Passed on? A Study on the Association between Early Maladaptive Schemas in Parents and Their Offspring and the Putative Translating Mechanisms. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2018, 46, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonnevijlle, M.; Hildebrand, M. Like parent, like child? Exploring the association between early maladaptive schemas of adolescents involved with C hild P rotective S ervices and their parents. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2018, 24, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.; Francis, A.J.P. Intergenerational Transfer of Early Maladaptive Schemas in Mother–Daughter Dyads, and the Role of Parenting. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2019, 43, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, D.; Høifødt, R.S.; Bohne, A.; Landsem, I.P.; Wang, C.E.A.; Thimm, J.C. Early maladaptive schemas as predictors of maternal bonding to the unborn child. BMC Psychol. 2019, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynel, Z.; Uzer, T. Adverse childhood experiences lead to trans-generational transmission of early maladaptive schemas. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 99, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaarslan, C.; Eldogan, D.; Yigit, I. Associations between early maladaptive schema domains of parents and their adult children: The role of defence styles. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 28, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaftar, I.; Uzer, T. Understanding intergenerational transmission of early maladaptive schemas from a memory perspective: Moderating role of overgeneral memory on adverse experiences. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 127, 105539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barazandeh, H.; Kissane, D.; Saeedi, N.; Gordon, M. Schema modes and dissociation in borderline personality disorder/traits in adolescents or young adults. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.A.; Hill, K.G.; Oesterle, S.; Hawkins, J.D. Parenting practices and problem behavior across three generations: Monitoring, harsh discipline, and drug use in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1214–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudino, A.; Fergusson, D.M.; Woodward, L.J.; Horwood, L.J. The intergenerational transmission of conduct problems. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 48, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, K.S.; Behling, S.; Li, Y.; Parikshak, S.; Gershenson, R.A.; Feuer, R.; Danko, C.M. Measuring Attitudes Toward Acceptable and Unacceptable Parenting Practices. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2011, 21, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-H.; Tam, W.-C.C.; Chang, K. Early Maladaptive Schemas, Depression Severity, and Risk Factors for Persistent Depressive Disorder: A Cross-sectional Study. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2019, 29, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, T.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Krug, I. Insecure attachment and maladaptive schema in disordered eating: The mediating role of rejection sensitivity. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 24, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguzzo, P.; Cazzola, C.; Castegnaro, R.; Buscaglia, F.; Bucci, E.; Pillan, A.; Garolla, A.; Bonello, E.; Todisco, P. Associations Between Trauma, Early Maladaptive Schemas, Personality Traits, and Clinical Severity in Eating Disorder Patients: A Clinical Presentation and Mediation Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 661924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelofs, J.; Onckels, L.; Muris, P. Attachment Quality and Psychopathological Symptoms in Clinically Referred Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Early Maladaptive Schema. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 22, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Disconnection and Rejection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional deprivation | Abandonment/Instability | Mistrust/Abuse | Social isolation/Alienation | Defectiveness/Shame |

| A conviction that basic emotional needs for nurturance, empathy, and protection cannot be adequately met by others | An expectation that relationships with others are unstable, insecure, fragile, and may end unexpectedly | Anticipating that others will intentionally harm, punish, humiliate, or take advantage | A feeling of a deep separation from society, not belonging to any community | A belief that one cannot be loved and accepted because of being flawed, inferior, bad, or imperfect |

| Impaired autonomy and performance | ||||

| Failure to achieve | Dependence/incompetence | Vulnerability to harm or illness | Enmeshment/undeveloped self | |

| A belief that one does not have sufficient competences, talents, and intelligence to achieve results alike others in terms of career, education, and achievements. | A feeling of being completely helpless, powerless, unable to function independently | An expectation that the world is full of unpredictable catastrophes, threats, dangers, and a person has no resources to deal with it | Excessive, emotional involvement in the life of a loved one (s), associated with a sense of identity fusion or blurring, and the fear that one person cannot survive without the constant devotion to the other | |

| Impaired limits | ||||

| Entitlement/grandiosity | Insufficient self-control/self-discipline | |||

| A belief in one’s own superiority over others, having special privileges or being above the applicable laws and rules | Recurring difficulties with self-control, emotional management, frustration tolerance, deferring gratification | |||

| Other directedness | ||||

| Subjugation | Self-sacrifice | Approval-seeking/Recognition-seeking | ||

| The belief that one must submit to the will of others in order to avoid negative consequences (e.g., punishment, conflict, rejection) | The conviction that satisfying the needs of others should be inviolably placed above one’s own | Excessive concentration on attention, acceptance and appreciation of the social environment, on which a person depends for self-esteem | ||

| Over-vigilance and inhibition | ||||

| Emotional inhibition | Unrelenting standards/hypercriticalness | Negativity/pessimism | Punitiveness | |

| An absolute imperative to keep control over one’s feelings, emotional reactions, and impulses, in order to avoid feelings of shame, rejection, disapproval | A belief that, regardless of the efforts put in, one will never be good enough and never live up to expectations, which results in rigid behavior, perfectionism, and denying oneself the pleasure | A perception of life through the prism of negative aspects, deficiencies, flaws, and minimizing its positive aspects, often combined with a tendency to worry | A belief that people should be severely punished for their mistakes combined with an attitude of intolerance, inexcusability | |

| Year/ Location | Author | Sample Size | Characteristic of Participants | Objective | Assessment Measures * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012, USA | Shorey, Anderson, Stuart [29] | Total: 105 | The total number of participants was 105. Substance abuse treatment-seeking adults: Males = 32, Females = 15 Age: M = 29.63, SD = 9.57 Parents: Mothers = 13, Fathers = 45 Age: M = 58.13, SD = 8.66 | To consider similarities and differences in EMSs among a sample of substance abuse treatment-seeking adults and at least one parent. |

|

| 2016, Poland | Mącik, Chodkiewicz, Bielicka [30] | Total: 80 | The total number of participants was 20 full families with grown children: a daughter and a son. Grown children: Age: M = 27.83, SD = 3.26 Parents: Age: M = 53.83, SD = 4.28 | To explore the relations between dysfunctional parents’ EMSs and their parental attitudes and their children’ EMSs. |

|

| 2017, Hungary | Miklósi, Szabó, Simon [31] | Total: 145 | The total number of participants was 145 caregivers, 1 excluded due to incomplete data. There were 122 mothers, and 19 fathers, and 3 other caregivers. Children: Males = 48, Females = 96 Age: M = 10.58, SD = 5.50 Parents: Age: M = 40.36, SD = 6.65 | To test the associations between parents’ perceptions of their own aversive childhood experiences with their caregivers, the extent of their EMSs, and their current level of perceived parenting competence. Secondly, to explore whether parents’ level of mindfulness is moderating or mediating this relationship. |

|

| 2018, Germany | Sundag, et al. [32] | Total 120 | The total number of participants was 60 parent–adult child dyads. Grown children: Daughter =38, Son = 22 Age: M = 28.4, SD = 9.4 Parents: Mothers = 49, Fathers = 11 Age: M = 57.8, SD = 8.7 | To investigate whether the extent of EMSs in parents is associated with the extent of EMSs in their offspring. |

|

| 2018, Netherlands | Zonnevijlle, Hildebrand [33] | Total: 40 | The total number of participants was 20 parent–adolescent dyads. Adolescents: Males = 13, Females = 7 Age: M = 16.2 years, SD = 1.6 Parents: Mothers = 19, Fathers = 1 Age: M = 45.6 years, SD = 8.1 | To examine the interrelationships of and differences between EMSs among maltreated children and their parents. |

|

| 2019, Australia | Gibson, Francis [34] | Total: 100 | The total number of participants was 100. There were 43 mothers and 57 adult daughters; 41 were matched in dyads and 39 included in the analysis. Adult daughters: Age: M = 26.28, SD = 9.33 Mothers: Age: M = 55.74, SD = 8.75 | To verify the potential mediating role of parenting styles in relationships between mothers’ and daughters’ EMSs. |

|

| 2019, Norway | Nordahl, et al. [35] | Total: 165 | The total number of participants was 165 pregnant women. Age: M = 30.8, SD = 4.1 | To examine the relationship between mothers’ EMSs and two aspects of maternal–fetal bonding: the intensity of preoccupation with the fetus and the quality of the affective bond. |

|

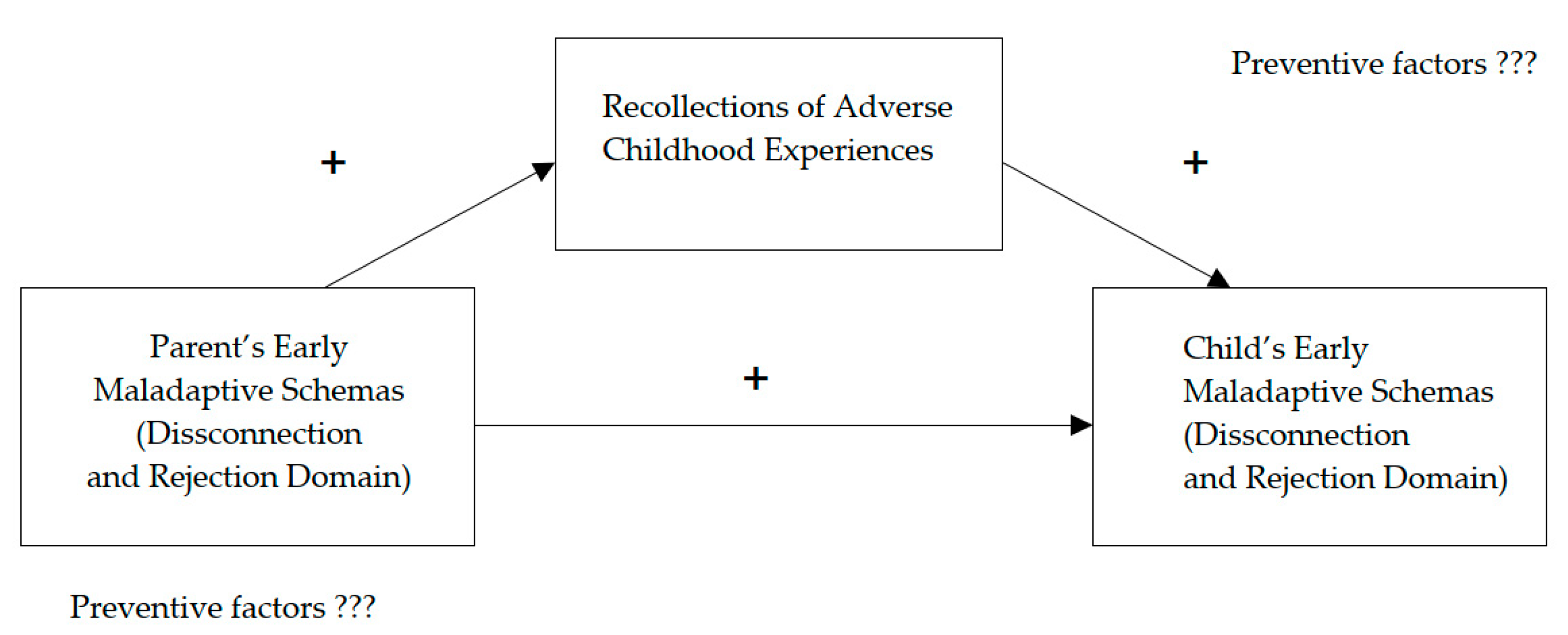

| 2020, Turkey | Zeynel, Uzer [36] | Total: 358 | The total number of participants was 179 mother–late adolescent dyads. Late adolescent: Males = 83, Females = 95, Unwilling to report = 1 Age: M = 20.52, SD = 1.16 Mothers = 179 Age: M = 47.64, SD = 5.31 | To test the mechanisms underlying the relationship between the parent’s disconnection and rejection schemas and the child’s disconnection and rejection schemas. |

|

| 2021, Turkey | Karaarslan, Eldogan, Yigit [37] | Total: 626 | The total number of participants was 215 families (i.e., mother, father, and their adult children) Adolescents: Males = 66, Females = 149 Age: M = 20.82, SD = 2.71 Mothers = 201 Age: M = 48.38, SD = 5.15 Fathers = 210 M = 52.08, SD = 5.55 | To evaluate the mediating role of defense styles in the associations between two EMS domains (Disconnection/Rejection and Impaired Autonomy) of parents and their adult children. |

|

| 2022, Turkey | Alaftar, Uzer [38] | Total: 240 | The total number of participants was 120 mother–late adolescent dyads. Adolescents Age: M = 21.78, SD = 1.50 Mothers Age: M: 49.93, SD = 4.56 | To examine whether overgeneral autobiographical memory facilitates the transmission of early maladaptive schemas (EMSs) by strengthening maladaptive thinking patterns after traumatic experiences. |

|

| Author, Year | Main Results and Conclusions |

|---|---|

| 2012 Shorey, Anderson, Stuart [29] | Lack of support for the hypothesis of the intergenerational transmission of early maladaptive schemas until parents showed high scores for most EMSs. Significantly higher scores in 17 out of 18 EMSs (early maladaptive schemas) of substance abusers seeking treatment than their parents. |

| 2016 Mącik, Chodkiewicz, Bielicka [30] | Support for the hypothesis that early maladaptive schemas may be transmitted intergenerationally, however not in a straight way. Children’s EMSs become the answer to parents’ EMSs, in the case of daughters, more complementary, in the case of sons, the reverse. |

| 2017 Miklósi, Szabó, Simon [31] | Self-reports of childhood neglect are significantly related to higher EMSs scores and correlate with the caregivers’ current sense of competence in their own parenting roles. Higher intensity of EMSs is related to lower levels of mindfulness, and consequently with lower levels of parental competence. |

| 2018 Sundag, et al. [32] | The extent of parents’ EMSs is a significant predictor of the intensity of a child’s EMSs. The parental schema coping style of Overcompensation and the adverse parenting that the child remembered are assumed to underlie the intergenerational transmission of EMSs. |

| 2018 Zonnevijlle, Hildebrand [33] | Unrelenting standards schema demonstrate significant positive association between parents and youth scores. There are substantial correlations between parents’ schemas of the Impaired limits and Disconnection/rejection domains and children’s schemas of the Disconnection/rejection and Impaired autonomy and performance domains. |

| 2019 Gibson, Francis [34] | Daughters’ schemas of Subjugation and Approval seeking are most strongly associated with overall mothers’ schemas. Mothers’ schemas in the Disconnection/Rejection domain are significantly related to daughters’ overall schema scores. An abandonment and Mistrust/Abuse schema of mothers and daughters are directly related. |

| 2019 Nordahl, et al. [35] | Significant, negative correlation between all domains of EMSs and the quality of the maternal–fetal bonding. The Disconnection and Rejection domain as a significant, independent predictor of the quality of maternal–fetal bonding. Depressive symptoms mediate the effect between pregnant women’s EMSs domains (Disconnection and Rejection, Impaired Autonomy and Performance, and Impaired Limits) and the quality of the maternal–fetal bond. |

| 2020 Zeynel, Uzer [36] | Mediating role of adverse childhood experiences in the relationship between mother’s Disconnection and Rejection domain schemas and her child’s Disconnection and Rejection domain schemas. Protective role of fathers involvement in childcare against intergenerational transmission of EMSs. |

| 2021 Karaarslan, Eldogan, Yigit [37] | Significant correlations between parents’ and their adult children’s Disconnection and Rejection and Impaired Autonomy EMSs domains were found. Mediating influence of immature defense styles of parents and their adult children. |

| 2022 Alaftar, Uzer [38] | Support for hypothesis that adverse childhood experiences significantly mediated the relationship between mothers’ and children’s disconnection and rejection schemas. Overgeneral autobiographical memory can intensify the association between adverse childhood experiences and children’s Disconnection and Rejection schemas. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sójta, K.; Strzelecki, D. Early Maladaptive Schemas and Their Impact on Parenting: Do Dysfunctional Schemas Pass Generationally?—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041263

Sójta K, Strzelecki D. Early Maladaptive Schemas and Their Impact on Parenting: Do Dysfunctional Schemas Pass Generationally?—A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(4):1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041263

Chicago/Turabian StyleSójta, Klaudia, and Dominik Strzelecki. 2023. "Early Maladaptive Schemas and Their Impact on Parenting: Do Dysfunctional Schemas Pass Generationally?—A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 4: 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041263

APA StyleSójta, K., & Strzelecki, D. (2023). Early Maladaptive Schemas and Their Impact on Parenting: Do Dysfunctional Schemas Pass Generationally?—A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(4), 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041263