Transferrin Biosynthesized in the Brain Is a Novel Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Glycan Structures of CSF Transferrin

2.2. Immunoprecipitation of CSF Transferrin

2.3. Lack of Man-Tf in CSF of Hydranencephaly Patients

2.4. Expression of Tf mRNA and Tf protein in the Cerebral Cortex

2.5. Glycan Analysis of Tf in the Cerebral Cortex

2.6. Man-Tf Levels in the CSF of Patients with Different Neurological Diseases

2.7. Expression of p-tau and Man-Tf in Hippocampus of AD Patients

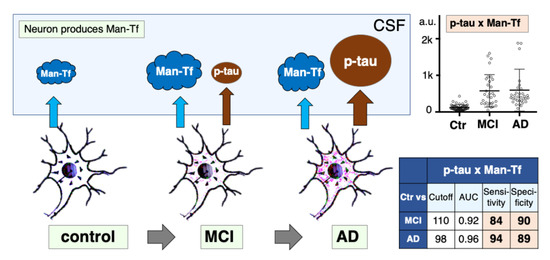

2.8. Diagnostic Accuracy of Man-Tf and Its Combination with P-tau

3. Discussion

4. Limitations

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Patients

5.2. Glycan Analysis of Transferrin Purified from CSF and Cerebral Cortex

5.3. SDS-PAGE and Blotting Analyses

5.4. Preparation of Authentic Tf Isoforms

5.5. Immunoprecipitation of CSF Tf

5.6. ELISA for CSF Proteins

5.7. Preparation of Tissue Sections and Pairs of Mirror Image Sections

5.8. In Situ Hybridization (ISH)

5.9. Immunohistochemistry

5.10. Statistical Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalaria, R.N.; Maestre, G.E.; Arizaga, R.; Friedland, R.P.; Galasko, D.; Hall, K.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Ogunniyi, A.; Perry, E.K.; Potocnik, F.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: Prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bloom, G.S. Amyloid-beta and tau: The trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, K.; Alonso, A.D.C.; Chen, S.; Chohan, M.O.; El-Akkad, E.; Gong, C.X.; Khatoon, S.; Li, B.; Liu, F.; Rahman, A.; et al. Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2005, 1739, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blennow, K.Z.H. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: Current status and prospects for the future. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 284, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tapiola, T.; Alafuzoff, I.; Herukka, S.K.; Parkkinen, L.; Hartikainen, P.; Soininen, H.; Pirttilä, T. Cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42 and tau proteins as biomarkers of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in the brain. Arch. Neurol. 2009, 66, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fagan, A.M.; Shaw, L.M.; Xiong, C.; Vandersticheles, H.; Mintun, M.A.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Coart, E.; Morris, J.C.; Holzman, D.M. Comparison of analytical platforms for cerebrospinal fluid measures of Abeta1-42, total tau and p-tau181 for identifying Alzheimer’s disease amyloid plaque pathology. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olsson, B.; Lautner, R.; Andreasson, U.; Öhrfelt, A.; Portelius, E.; Bjerke, M.; Hölttä, M.; Rosén, C.; Olsson, C.; Strobel, G.; et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Neurol. 2016, 15, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, C.; Smailagic, N.; Noel-Storr, A.H.; Ukoumunne, O.; Ladds, E.C.; Martin, S. CSF tau and the CSF tau/ABeta ratio for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD010803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Counts, S.E.; Ikonomovic, M.D.; Mercado, N.; Vega, I.E.; Mufson, E.J. Biomarkers for the Early Detection and Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mizutani, K.; Toyoda, M.; Mikami, B. X-ray structures of transferrins and related proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2012, 1820, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, G.; van Dijk, J.P.; van Eijk, H.G. The biology of transferrin. Clin. Chim. Acta 1990, 190, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.; Nimtz, M.; Getzlaff, R.; Conradt, H.S. ‘Brain-type’ N-glycosylation of asialo-transferrin from human cerebrospinal fluid. FEBS Lett. 1995, 359, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Futakawa, S.; Nara, K.; Miyajima, M.; Kuno, A.; Ito, H.; Kaji, H.; Shirotani, K.; Honda, T.; Tohyama, Y.; Hoshi, K.; et al. A unique N-glycan on human transferrin in CSF: A possible biomarker for iNPH. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagae, M.; Morita-Matsumoto, K.; Arai, S.; Wada, I.; Matsumoto, Y.; Saito, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y. Structural change of N-glycan exposes hydrophobic surface of human transferrin. Glycobiology 2014, 24, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murakami, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Hoshi, K.; Ito, H.; Fuwa, T.J.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Nakajima, M.; Miyajima, M.; Arai, H.; Nollet, K.; et al. Rapid increase of ‘brain-type’ transferrin in cerebrospinal fluid after shunt surgery for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: A prognosis marker for cognitive recovery. J. Biochem. 2018, 164, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Hoshi, K.; Ito, H.; Kanno, M.; Saito, K.; Nollet, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Miyajima, M.; Arai, H.; et al. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension is diagnosed by a combination of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase and brain-type transferrin in cerebrospinal fluid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2018, 1862, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Saito, K.; Ito, H.; Hashimoto, Y. Transferrin isoforms in cerebrospinal fluid and their relation to neurological diseases. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2019, 95, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamilton, R.; Patel, S.; Lee, E.B.; Jackson, E.M.; Lopinto, J.; Arnold, S.E.; Clark, C.M.; Basil, A.; Shaw, L.M.; Xie, S.X.; et al. Lack of shunt response in suspected idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus with Alzheimer disease pathology. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 68, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pomeraniec, I.J.; Bond, A.E.; Lopes, M.B.; Jane, J.A. Concurrent Alzheimer’s pathology in patients with clinical normal pressure hydrocephalus: Correlation of high-volume lumbar puncture results, cordical brain biopsies, and outcomes. J. Neuosurgery 2016, 124, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Castillo, E.L.J.; Mazzei, G.; Abolhassani, N.; Haruyama, N.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.; Hokama, M.; Iwaki, T.; Ohara, T.; Ninomiya, T.; et al. Comparative profiling of cortical gene expression in Alzmeimer’s disease patients and mouse models demonstrates a link between amyloidosis and neuroinflammation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tatebe, H.; Kasai, T.; Ohmichi, T.; Kishi, Y.; Kakeya, T.; Waragai, M.; Kondo, M.; Allsop, D.; Tokuda, T. Quantification of plasma phosphorylated tau to use as a biomarker for brain Alzheimer pathology: Pilot case-control studies including patients with Alzheimer’s disease and down syndrome. Mol. Neurodegener 2017, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barthélemy, N.R.; Horie, K.; Sato, C.; Bateman, R.J. Blood plasma phosphorylated-tau isoforms track CNS change in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20200861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscoso, A.; Grothe, M.J.; Ashton, N.J.; Karikari, T.K.; Rodriquez, J.L.; Snellman, A.; Suarez-Calvet, M.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Scholl, M. Longitudinal Associations of Blood Phosphorylated Tau181 and Neurofilament Light Chain With Neurodegenation in Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissin, D.M.; Kan, C.W.; Campbell, T.G.; Howes, S.C.; Fournier, D.R.; Song, L.; Piech, T.; Patel, P.P.; Chang, L.; Rivnak, A.J.; et al. Single-Molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taniguchi, M.O.Y.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kitaura, M.; Jinbo, D.; Wakutani, Y.; Wada-Isoe, K.; Nakashima, K.; Akatsu, H.; Furukawa, K.; Arai, H.; et al. Sugar chains of cerebrospinal fluid transferrin as a new biological marker of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2008, 26, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.S.; DeKosky, S.T.; Dickson, D.; Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Fox, N.C.; Gamst, A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.J.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Litvan, I.; Agid, Y.; Jankovic, J.; Goetz, C.; Brandel, J.P.; Lai, E.C.; Wenning, G.; D’Olhaberriague, L.; Verny, M.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; et al. Accuracy of clinical criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome). Neurology 1996, 46, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, D.; Snowden, J.; Gustafson, L.; Passant, U.; Stuss, D.; Black, S.; Freedman, M.; Kertesz, A.; Robert, P.H.; Albert, M.; et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 1998, 51, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McKeith, I.G.; Boeve, B.F.; Dickson, D.W.; Halliday, G.; Taylor, J.P.; Weintraub, D.; Aarsland, D.; Galvin, J.; Attems, J.; Ballard, C.G.; et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2017, 89, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mori, E.; Ishikawa, M.; Kato, T.; Kazui, H.; Miyake, H.; Miyajima, M.; Nakajima, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Kuriyama, N.; Tokuda, T.; et al. Guidelines for management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: Second edition. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2012, 52, 775–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shirotani, K.; Futakawa, S.; Nara, K.; Hoshi, K.; Saito, T.; Tohyama, Y.; Kitazume, S.; Yuasa, T.; Miyajima, M.; Arai, H.; et al. High Throughput ELISAs to Measure a Unique Glycan on Transferrin in Cerebrospinal Fluid: A Possible Extension toward Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarker Development. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 2011, 352787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ito, H.; Hoshi, K.; Honda, T.; Hashimoto, Y. Lectin-Based Assay for Glycoform-Specific Detection of alpha2,6-sialylated Transferrin and Carcinoembryonic Antigen in Tissue and Body Fluid. Molecules 2018, 23, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Saito, T.; Hoshi, K.; Ito, H.; Kariya, Y.; Nagae, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Hagiwara, Y.; Kinoshita, N.; Wada, I.; et al. In situ visualization of a glycoform of transferrin: Localization of alpha2,6-sialylated transferrin in the liver. J. Biochem. 2015, 157, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Enya, M.; Morishima-Kawashima, M.; Yoshimura, M.; Shinkai, Y.; Kusui, K.; Khan, K.; Games, D.; Shenk, D.; Sugihara, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; et al. Appearance of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Stable Amyloid beta-Protein (Abeta) Dimer in the Cortex During Aging. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 154, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | Age * (Years) | Patient Number | Gender (M/F) | MMSE * | Aβ40 * (pg/mL) | Aβ42 * (pg/mL) | p-tau * (pg/mL) | Tau * (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iNPH: idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus | 77.5 ± 6.9 | 52 | 30/22 | 22.4±5.5 | 3600 ± 1260 | 312 ± 207 | 27.9 ± 10 | 191 ± 48 |

| MCI: mild cognitive impairment | 76.0 ± 6.9 | 42 | 19/23 | 26.9 ± 1.7 | 7260 ± 3180 | 630 ± 268 | 65.7 ± 30 | 428 ± 220 |

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease | 73.5 ± 8.7 | 61 | 27/34 | 20.4 ± 4.2 | 5620 ± 2750 | 537 ± 182 | 85.1 ± 46 | 652 ± 260 |

| PSP: progressive supranuclear palsy | 69.6 ± 5.7 | 7 | 4/3 | n.d. | 5810 ± 2890 | 611 ± 337 | 33.9 ± 6.8 | 194 ± 64 |

| FTD: frontotemporal degeneration | 60.7 ± 4.1 | 10 | 5/5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 45.5 ± 32 | 360 ± 290 |

| DLB: dementia with Lewy bodies | 66.8 ± 2.6 | 9 | 6/3 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 39.3 ± 4.4 | 184 ± 75 |

| PD: Parkinson’s disease | 68.2 ± 8.5 | 34 | 13/21 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 37.8 ± 9.8 | 187 ± 75 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoshi, K.; Ito, H.; Abe, E.; Fuwa, T.J.; Kanno, M.; Murakami, Y.; Abe, M.; Murakami, T.; Yoshihara, A.; Ugawa, Y.; et al. Transferrin Biosynthesized in the Brain Is a Novel Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease. Metabolites 2021, 11, 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11090616

Hoshi K, Ito H, Abe E, Fuwa TJ, Kanno M, Murakami Y, Abe M, Murakami T, Yoshihara A, Ugawa Y, et al. Transferrin Biosynthesized in the Brain Is a Novel Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease. Metabolites. 2021; 11(9):616. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11090616

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoshi, Kyoka, Hiromi Ito, Eriko Abe, Takashi J. Fuwa, Mayumi Kanno, Yuta Murakami, Mitsunari Abe, Takenobu Murakami, Akioh Yoshihara, Yoshikazu Ugawa, and et al. 2021. "Transferrin Biosynthesized in the Brain Is a Novel Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease" Metabolites 11, no. 9: 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11090616

APA StyleHoshi, K., Ito, H., Abe, E., Fuwa, T. J., Kanno, M., Murakami, Y., Abe, M., Murakami, T., Yoshihara, A., Ugawa, Y., Saito, T., Saido, T. C., Matsumoto, K., Yamaguchi, Y., Furukawa, K., Arai, H., Kanai, M., Miyajima, M., Arai, H., ... Hashimoto, Y. (2021). Transferrin Biosynthesized in the Brain Is a Novel Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease. Metabolites, 11(9), 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11090616