Abstract

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain tumor in adults. Thalidomide is a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor that demonstrates antiangiogenic activity, and may provide additive or synergistic anti-tumor effects when co-administered with other antiangiogenic medications. This study is a comprehensive review that highlights the potential benefits of using thalidomide, in combination with other medications, to treat glioblastoma and its associated inflammatory conditions. Additionally, the review examines the mechanism of action of thalidomide in different types of tumors, which may be beneficial in treating glioblastoma. To our knowledge, a similar study has not been conducted. We found that thalidomide, when used in combination with other medications, has been shown to produce better outcomes in several conditions or symptoms, such as myelodysplastic syndromes, multiple myeloma, Crohn’s disease, colorectal cancer, renal failure carcinoma, breast cancer, glioblastoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma. However, challenges may persist for newly diagnosed or previously treated patients, with moderate side effects being reported, particularly with the various mechanisms of action observed for thalidomide. Therefore, thalidomide, used alone, may not receive significant attention for use in treating glioblastoma in the future. Conducting further research by replicating current studies that show improved outcomes when thalidomide is combined with other medications, using larger sample sizes, different demographic groups and ethnicities, and implementing enhanced therapeutic protocol management, may benefit these patients. A meta-analysis of the combinations of thalidomide with other medications in treating glioblastoma is also needed to investigate its potential benefits further.

1. Introduction

Glioblastoma is adults’ most common malignant primary brain tumor [1]. Maximal safe surgical resection followed by radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy is the glioblastoma standard treatment protocol [2]; however, the median survival is short, only about 14 to 16 months, and a 5-year overall survival rate of less than 10% [3]. Glioblastomas are considered solid tumors. They are composed of heterogeneous cancer cells that create new blood vasculatures, inflammatory elements, and stromal environments [4,5,6,7]. The most important factor in diagnosing glioblastoma is the detection of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations. According to that, the 2021 Fifth Edition World Health Organization Classification of central nervous system (CNS) tumors has classified glioblastoma into two groups: IDH–wild-type glioblastoma (hereinafter referred to as GBM for simplicity) (95%) and IDH–mutant astrocytoma (5%) [2]. GBM accounts for 45.2% of primary malignant brain and CNS tumors, with a yearly incidence rate of 3.19 per 100,000 people [1].

During recurrent GBM, chemotherapy remains the most effective approach, because patients cannot redo surgeries or irradiation [8]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a prominent mediator of tumor angiogenesis [9,10], and there is increasing scientific interest in studying VEGF inhibitors. Bevacizumab was the first antiangiogenic drug to treat GBM, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Bevacizumab is used as a single medication in patients with GBM who have progressive disease following front-line therapy that consists of surgical resection, radiotherapy, and temozolomide [6,11,12,13]. The tumor-initiating cells (TICs) and glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) play an essential role in GBM development, via different processes starting at the subventricular zone along ventricles underlying driver mutations. Both cell types have stem cell characteristics such as self-renewal, differentiation, and a low rate of proliferation. These features of GSCs contribute to chemotherapy resistance by increasing the drug efflux pump, drug degradation, DNA repair, and decreasing the drug influx pump, the activation of prodrugs. For example, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH) and O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) are overexpressed in GBM, and decrease the activity of alkylating agents. The latter has a critical role in DNA repair, so the DNA methylation of the MGMT gene is associated with a better outcome and a high survival rate. Hypoxia is considered to be one of the characteristics of GBM; therefore, the GSCs can resist chemo- and radiotherapy through mitochondria modulation, which controls apoptosis and tumor cells’ necrosis [14,15].

Wang et al. showed that bevacizumab compared to thalidomide (THD) for recurrent GBM patients, improved the objective response rate (ORR) and 6-month median progression-free survival, but not the 1-year median overall survival [16]. Therefore, many clinical studies test new angiogenesis inhibitors to enhance GBM treatment results [17]. Moreover, highlighting different mechanisms of THD in vivo and in vitro will provide a higher chance of understanding cell behavior and resistance to anticancer therapies [18,19].

We conducted an exhaustive review of the literature, and aim to highlight the THD mechanism of action in vivo and in vitro and its usefulness when co-administered with other VEGF inhibitors to treat GBM. To the best of our knowledge, no similar study has been performed.

2. Genetic and Molecular Pathogenesis of GBM

The genetic features of IDH–wild-type glioblastoma include mutation in the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter; amplification of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR); loss of heterozygosity for 10q; deletion and point mutation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN); methylation of the MGMT promoter; a mutation in BRAF V600E. The features of IDH-mutant glioblastoma include mutation of ATRX (alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation, X-linked), TP53, DH1/IDH2, and PDGFRA (platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha) amplification, and loss of heterozygosity for 10q and 19q [2]. According to primary and secondary GBM, primary GBM has a mutation in PTEN (MMAC1), amplified EGFR, and chromosome 10 loss [20,21]. On the contrary, mutant IDH is more likely to occur in secondary GBM [22]. The IDH mutation is used as a marker for secondary GBM, and frequently occurs in more than 80% of cases; however, it rarely occurs in primary GBM, in around 5% of cases [23,24,25,26]. The amplification of EGFR in secondary GBM is rare, which tends to have TP53 mutations [27]. The differences in genetic and epigenetic profiles of primary and secondary GBM are not shown in histological examinations as different characteristics, even though they are believed to share different cell origins. Surprisingly, cells with mutated IDH1 and IDH2 tend to have better prognoses [28]. Methylation of MGMT prolongs survival compared to the unmethylated form of MGMT, which is involved in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) repair upon administrating alkylating treatment [29]. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) play an essential role in decreasing the activity of the T-cell response in glioma, and it is an immature heterogeneous group of cells recognized for their myeloid lineage [30]. MDSCs weaken the first line of defense by inhibiting the natural killer cell activation receptor (NKG2D), and decreases interferon-gamma (IFNγ) production while transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ) is present [31]. In addition to that, MDSCs also diminish adaptive immunity by disturbing the production of ARG1, inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase 2 (iNOS2), TGFβ, depletion of cysteine, and the down-regulation of CD62L (L-selectin) [32,33]. Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis in the solid tumor are correlated with a poor prognosis, due to their promotion by MDSCs [34].

3. Hypoxia, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, and Chemoresistance

GBM is characterized by hypoxic regions that are responsible for necrosis associated with GBM. The low-oxygen condition could activate the hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), critical transcriptional factors that play an essential role in a tumor’s response against hypoxia [35,36]. HIFs are believed to be sensors and proteins that are released in hypoxic regions responsible for cell adaption to low levels of oxygen, by optimizing the cellular processes that could initiate transcription factors activation of specific genes responsible for angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, and chemo-radio resistance in GBM [37,38,39,40,41]. The PTEN mutation (20–40%) and P53 mutation have been found in GBM. A loss of their function leads to the overexpression of HIF-1α. Moreover, HIF-1α can increase VEGF levels as one of the angiogenesis proteins. The level of VEGF in the cyst fluid of glioblastoma patients was found to be 200–300 fold more than in the serum.

During hypoxia, HIF-1α induces anaerobic glycolysis in GBM, resulting in a reduction in mitochondrial respiration, an increase in lactate levels and tumor acidity, and an interruption in the pH ratio between the intracellular and extracellular matrix that could decrease the passive absorption for many drugs, therefore increasing the probability of drug resistance [42,43]. Several studies reported that as the tumor size increases, the pH decreases. An acidic pH also plays an essential role in regulating cell proliferation, angiogenesis, immunosuppression, invasion, and chemoresistance in solid tumors [44,45,46,47,48]. Vaupel et al. reported that the pH could vary among the localized region of the tumor [48]. Normal brain tissue has a pH of 7.1, and in brain tumors it can be 5.9 [49]. Interestingly, upon performing electrode measurements, Hjelmeland et al. [49] reported a significant reduction in pH at the edge of the tumor compared with that in normal tissues. Moreover, the pH at the center of the tumor was even lower. Such a shift in the pH in gliomas, and the low pH, may increase angiogenesis through the induction of VEGF [50,51]. Acidic stress in GSCs promotes the HIF-2α protein. In low pH, HIF-2α mRNA increased 7-fold in cultures used for GSCs; however, HIF-1α mRNA was repressed. These findings hypothesize that HIF-2α could be responsible for inducing VEGF in acidic conditions [49]. Notably, the stability of HIFs is known to be regulated at the protein level as well, since HIFs have been found to be stable at low pH [52].

Other involvements of HIF-2α in GBM have also been reported. Li et al. [53] highlighted a higher expression level of HIF-2α in GSCs than in non-GSC. However, minimal expression of HIF-2α was found in normal adult murine neural progenitors under both conditions of hypoxia, and normoxia. Interestingly, HIF-1α was not as dramatically upregulated as HIF-2α in response to hypoxia in GSCs. The HIF-2α mRNA half-life time was found to be shorter in GSCs in comparison with non-GSCS. This indicates an increased de novo synthesis of mRNA of HIF-2α rather than the stabilization of mRNA of HIF-2α [53]. VEGF promoter activity was severely affected by the knock-down of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in hypoxic conditions, and decreased VEGF mRNA levels and intracellular and secreted VEGF protein levels. In contrast to non-stem glioma cells, only HIF-1α was required to regulate VEGF [53]. In another study, where the mesenchymal shift is the process where cells lose their adhesion and become migratory and invasive, it was found that HIF-1α-ZEB1, not the HIF-2α signaling axis, promoted this feature in GBM [54]. Another protein was associated with HIF-2α is teneurin transmembrane protein 1 (TENM1), a family of transmembrane proteins located on chromosome X. In vertebrates, their expression occurs during the central nervous system development, and is also associated with cellular signaling, cell proliferation, and adhesion regulations [55,56]. A recent study also reported that HIF-2α silencing decreased the expression of TENM1 [57]. Cancer stem cells show increased expressions of CD133 and HIF-2α when they are exposed to hypoxia [53,58,59,60].

As a result of hypoxia, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress occurs due to the accumulation of unfolded proteins and misfolded proteins because of the shortage of energy produced by the aerobic process; as the ERAD/ERAQ system does not work properly, it is becomes overburdened [61,62,63]. Consequently, it drives the cancer cell population in a similar fashion of selecting and allowing for the survival of the most resilient phenotype of glioma cells that can withstand hypoxic and endoplasmic reticulum stress, and are accustomed to resisting anti-tumor drugs [61,64]. The unregular and unorganized structure of solid tumor vasculature contributes to irregular drug delivery to the site of action, whereas the well-oxygenated regions are less susceptible to ER stress [65,66]. HIF-1α is associated with the multidrug resistance mutation 1 (MDR1) gene that is responsible for the expression of P-glycoprotein/ATP binding cassette transporter B1 [Pgp/ABCB1] [67]. Upon studying doxorubicin resistance, a direct link was found between HIF-1α and increased expression of P-glycoprotein (Pgp), which effluxes the medication outside the cell. [68]. It was observed that the efficacy of temozolomide was increased after the knockdown of HIF-1α, due to the down-regulation of DNA repair proteins [69,70].

4. Thalidomide Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action of THD has not been clearly defined or explained. Nevertheless, several studies suggest that THD is associated with immunity, inflammation modulators, and angiogenesis properties in tissues. THD actions have different complex effects on cytokines [71,72,73]. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), IFNγ, cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), and interleukins (ILs) IL-10 and IL-12 are among the inflammatory cytokines that THD effects [74]. THD primarily targets cereblon (CRBN), which decreases the release of cytokines TNFα and interleukins through degrading TNFα mRNA [71,72,75,76,77,78]. CRBN is a protein whose gene is found in human chromosome 3 [79]. CRBN’s role has not been clearly explained, although it is connected with ubiquitin ligase that binds to the damaged DNA binding protein (DDB1), Cullin-4A (CUL4A), and its regulators [80]. In addition, CRBN has also been associated with the large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel (KCNMA1) [81,82].

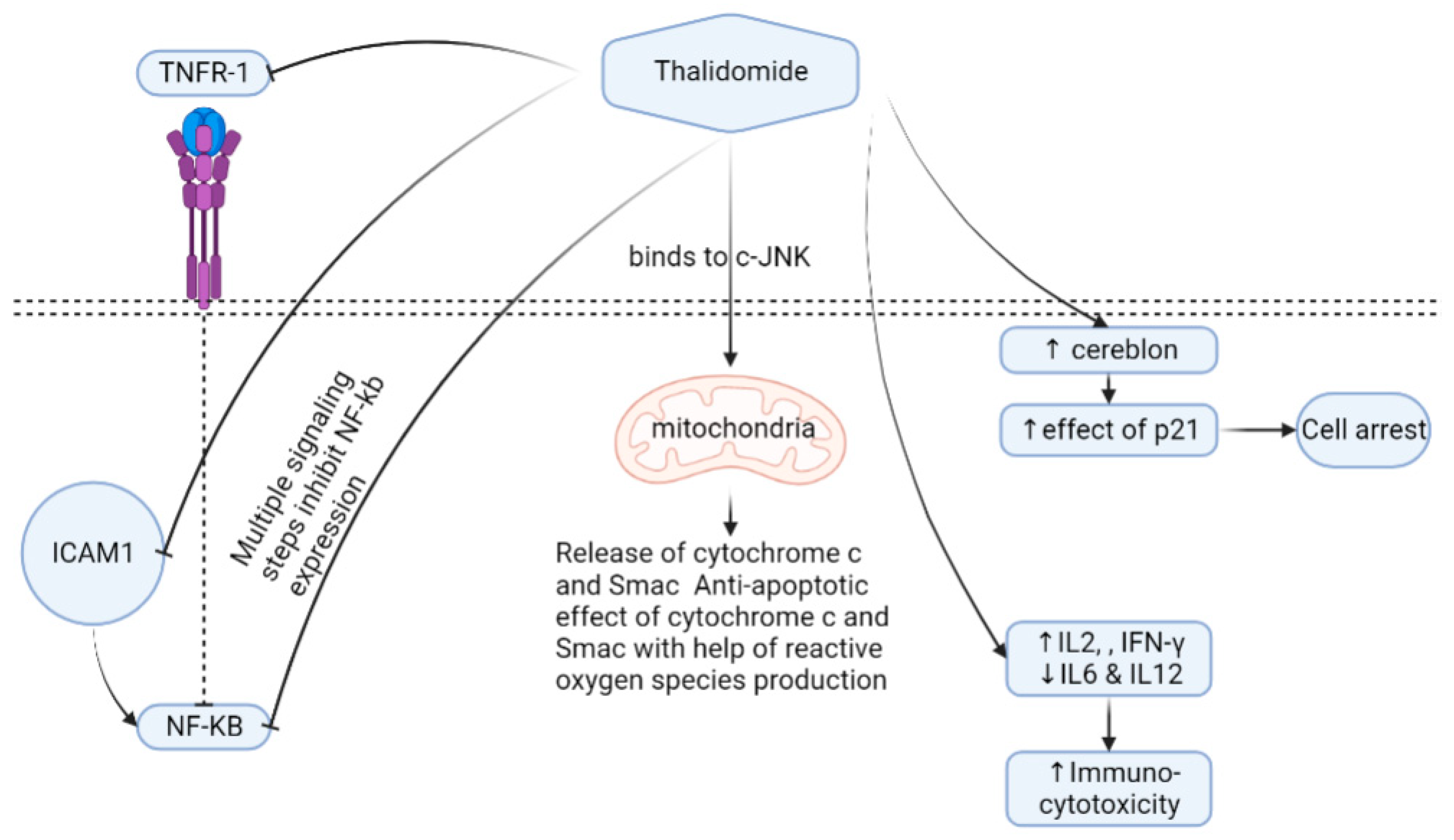

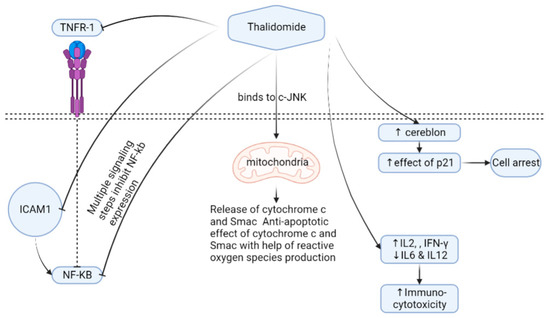

It is suggested that THD binding to CRBN limits angiogenesis ability, and helps generate reactive oxygen species [78,83]. THD induces T helper 2 (Th2) production; on the contrary, it inhibits the Th1 release in peripheral mononuclear cells [71] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Thalidomide mechanism of action. Cells expressing the cereblon protein show higher expressions of p21 if thalidomide is administrated, leading to cell arrest. Thalidomide can also increase immuno-cytotoxicity through the regulation of different cytokines. Thalidomide has a direct effect on mitochondria through binding to c-JNK, followed by releasing oxygen species. The inhibition of NF-KB occurs as a means for thalidomide by interacting with TNFR-1, ICOM1, and other multistep signaling. Abbreviations, c-JNK—c-jun terminal kinase; TNFR1—tumor necrosis factor receptor 1; IFN—interferon, IL—interleukin; NF-kB—nuclear factor-kappa B; Smac—second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases; ICAM1—intercellular adhesion molecule-1.

TNFα down-regulation causes nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) inhibition that results in lower levels of interleukin-6 transcriptions. Oppositely, THD up-regulates the caspase-8 protein widely used in myeloma by inducing caspase-8 myeloma cell programmed cell death apoptosis [84]. However, THD’s entire mechanism of action in reducing myeloma cells is still unclear. THD stimulates natural killer cells and T-lymphocytes, and prevents strong myeloma cells’ adhesion to bone marrow [85], thus affecting the composition of the bone marrow microenvironment [86]. THD has an antiangiogenic effect by blocking growth factors such as VEGFs and FGFβ [74,87,88,89,90]. Other studies have shown that THD inhibits HOXB7 [91] and Sp1 that have a binding site in the c-MYC promoter and suppress the TGFβ1-mediated non-SMAD ERK1/2 signaling pathways [92]. Several uses and mechanisms of actions in some clinical conditions exist in (Table 1) [93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117].

Table 1.

Thalidomide mechanism of action in vivo.

5. Thalidomide Efficacy

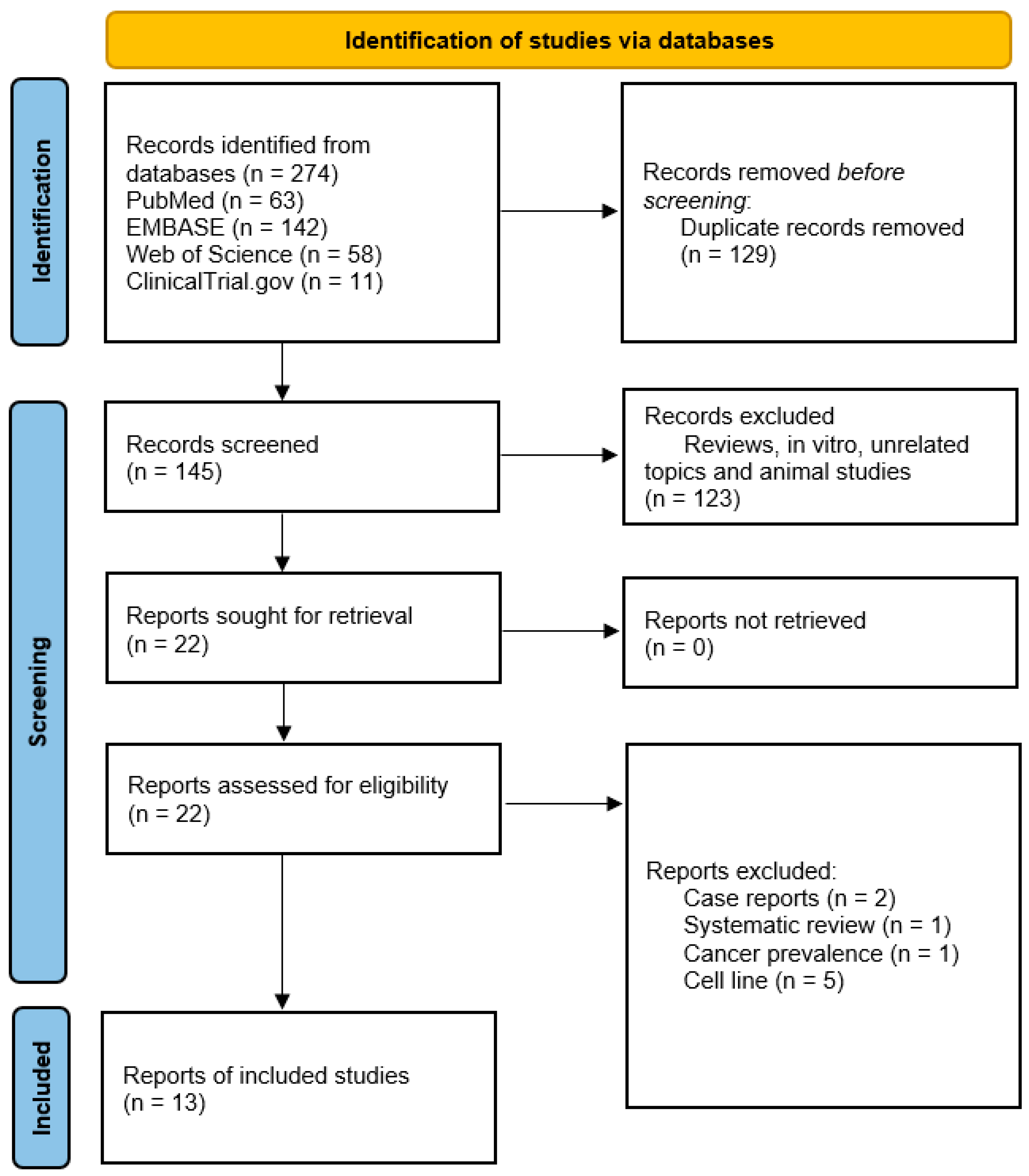

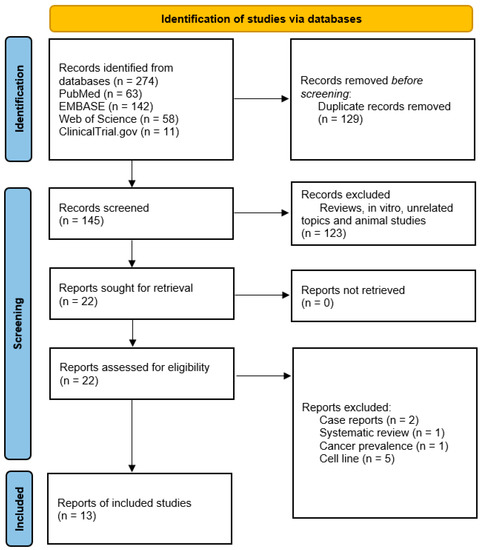

It has been over sixty years since THD has been on the market, and it is still frequently used in a wide range of therapeutic applications. The clinical trials and pharmacovigilance research have shown that THD is an effective medication in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), severe lung injuries caused by swine flu subtype H1N, and lung injuries caused by the toxic fast-acting herbicide called paraquat, with a well-defined mode of action [118]. To determine THD efficacy, we performed a systematic search on various databases, and reported the results of clinical trials that used THD for GBM treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA chart of the reported studies [119]. We included randomized control and single-arm studies demonstrating thalidomide efficacy in GBM treatment. During screening, we excluded review articles, in vitro studies, unrelated topics, and animal studies.

It has been shown that THD may be a promising therapeutic option for treating GBM through the following three trials conducted on patients with recurrent GBM who received conventional chemotherapy followed by THD [120,121,122]. During the trials, the daily dose of THD was between 100–1200 mg, with good tolerance in general, although there were uncommon responses. The first study included patients with recurrent GBM (n = 18), 77.8%. The median overall survival (OS) for 17 patients was 36 weeks (12–40) [123]. The second trial included patients with recurrent GBM (n = 42), 38 of whom were eligible for assessment; only 42% had stable disease, and 5% had a partial response. The OS was 31 weeks, and 35% of the patients achieved one-year survival [124]. The third trial included patients with recurrent GBM (n = 39), of whom 36 were eligible for assessment; only 33% had stable disease, 6% had a partial response, the OS was 28 weeks, and eight patients achieved one-year survival [125].

The use of THD concurrently with irinotecan has limited efficacy for the treatment of newly diagnosed or recurrent GBM; this was proven through two studies. In the first study (n = 26), 24 were eligible for assessment; only 79% had stable disease and 7% had a partial response. The six-month progression-free survival (PFS) of the recurrent group was 19%, and the six-months PFS of the newly diagnosed group was 40% [126]. In the second study, patients with recurrent GBM only (n = 32) were eligible for assessment. Only 19 patients had stable disease, one had a partial response, one had a complete response, the one-year OS was 34%, and the six-month PFS was 25% [127]. It is worth mentioning that THD was reported in eight studies to be an ineffective drug for the treatment of GBM [87,128,129,130,131,132,133].

A systematic review and meta-analysis compared only two cohorts of THD (n = 81) to 7 cohorts of bevacizumab (n = 351). The ORR favored bevacizumab over THD (RR 6.8, 95%CI 2.64–17.6; p < 0.001); however, both drugs showed comparable results in the progression-free survival and 1-year median overall survival rates (RR 1.68, 95%CI: 0.84–3.34, p = 0.07; and RR 0.89, 95%CI: 0.59–1.37; p = 0.31, respectively) [16]. In addition to using THD in the direct treatment of GBM, Hassler et al. [134] suggested using THD as a palliative treatment in patients with advanced secondary GBM. The patients (n = 23) were advised to administer 100 mg of THD at bedtime. Symptomatic improvement was most prominent in restoring a normal sleep pattern, and 47.8% of the patients survived longer than one year [134]. The palliative effects of THD can be a topic for further research. A list of the combined possible uses of THD with other drugs is shown in Table 2 [74,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155].

Table 2.

The combined uses of THD with multiple medications.

6. Thalidomide Safety

The proven teratogenicity of THD made it strictly prohibited from being used during pregnancy. Before THD may be taken, all patients have to be enrolled in the System for THD Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS) program. Prior to commencing treatment with THD, women of reproductive potentiality (less than two years postmenopausal) are required to show a negative pregnancy test. In addition, they have to use two different effective ways of birth control and be examined for pregnancy every four weeks; meanwhile, men who are going to take THD have to quit any sexual activities, or use condoms made of latex [121]. THD is known to cause many side effects, including numbness, nervousness, confusion, paresthesia, aural buzzing, nausea, up to 20%, increased appetite, 30% of burning sensation and deep vein thrombosis, 5% of bradycardia and neutropenia, 25% of skin rash, hangover feeling, decreased libido, edema, and hypothyroidism up to 25% [121]. THD’s common side effect was initially marketed as a sedative drug. The intensity of sedation tends to lessen with prolonged usage at a steady dose, which could be decreased and avoided by taking medicine at night three hours before bed. Constipation is a typical side effect that can vary depending on the dosage. Patients should be encouraged to eat food that contains a high amount of fiber, and to take laxatives as needed. In the case of dry skin side effects, it is pretty common to see it with pruritus, with the severity based on the drug’s dosage. Nevertheless, this effect may be reduced by using lubricants that are free of alcohol [83]

7. Thalidomide Toxicity

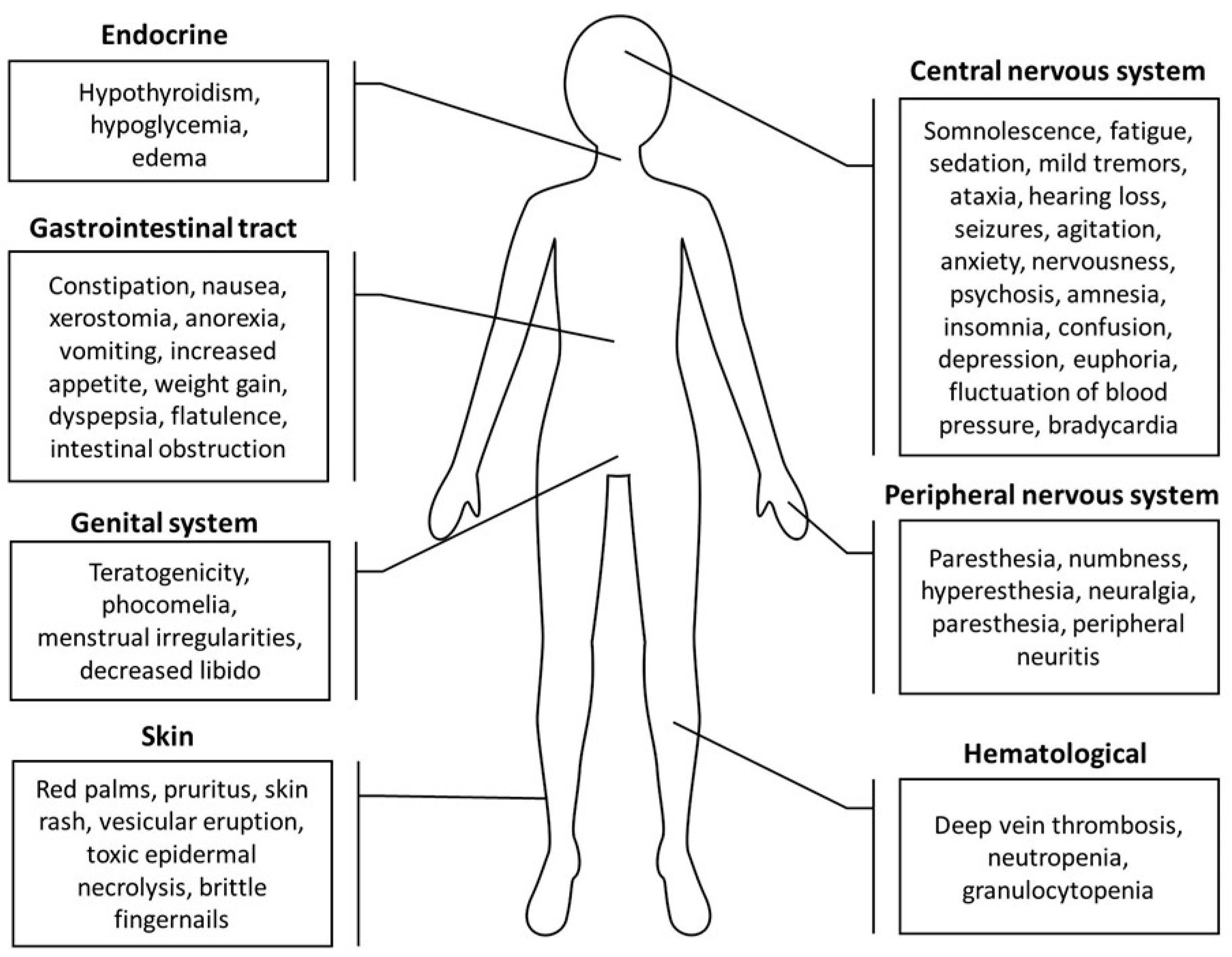

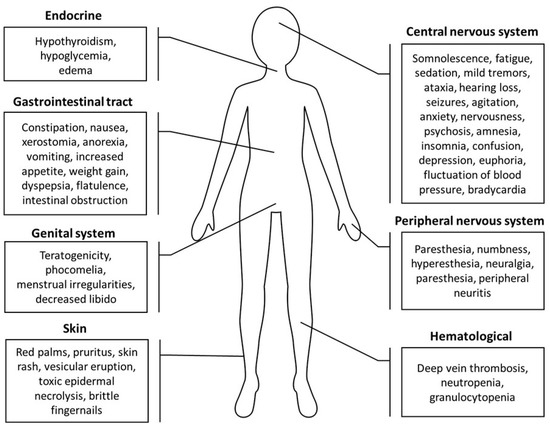

THD is known for its considerable risk to the unborn and developing child. As a result, THD and its derivatives are highly controlled, and necessitate the use of contraception when used as a therapy. Patients should cease using THD if they have serious side effects, especially neuropathic symptoms [156]. THD toxicity in the treatment protocol for patients with GBM was studied, and a trial was conducted on 39 patients; 26 received the full dosage of the THD regime. The results showed that the majority of patients tolerated THD well. However, four incidences were graded as 4 for cortical toxicity, and were all seizures. All of the participants in this experiment had a previous seizure history, and it was verified that tumor development increased during the activity of new seizures. Additionally, one incident involved constipation grade 1, and there were six incidences of grade 2 constipation episodes. Moreover, twelve patients had somnolence grade 1, three had grade 2, and six had grade 3. These were the most prevalent toxicities linked to THD [157]. A further phase II trial was conducted on 17 GBM patients to assess THD toxicity, and it was found that a few cases were graded. Two patients (17%) showed leukopenia progression grade 3–4 with neutropenia. Furthermore, other serious adverse events comprised (4 patients, 24%) those with fatigue grade 3. Moreover, another patient suffered from neurotoxicity grade 3. In this intervention sample, the medication-related toxicity had no clinical consequences, and no participant was discontinued from the experiment due to THD toxicity (Figure 3) [125].

Figure 3.

A summary of thalidomide side effects on the skin, gastrointestinal tract, central and peripheral nervous systems, genital system, endocrine system, and hematological system [72,156,158,159].

8. Thalidomide Drug Interactions

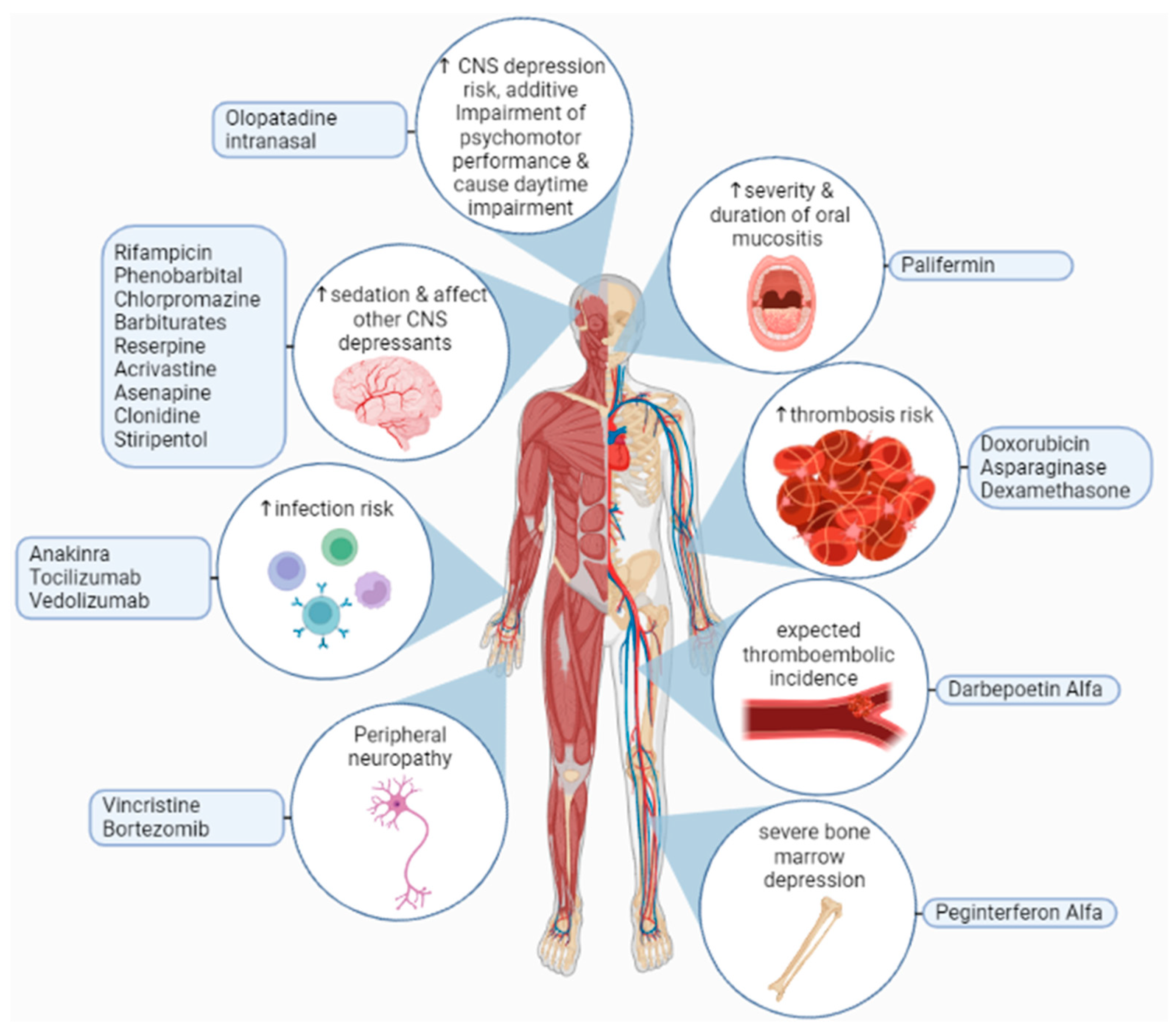

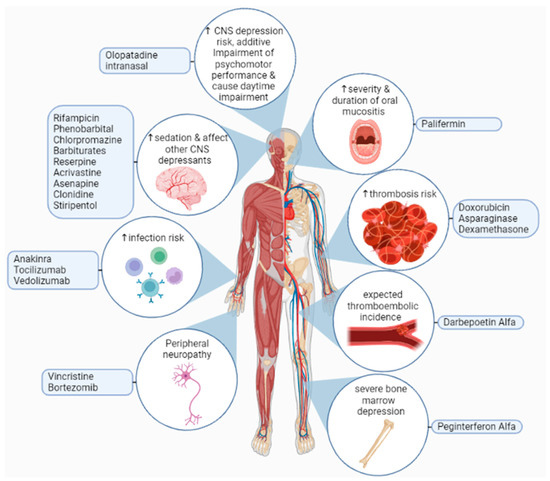

THD is mainly eliminated from the body by a hydrolysis reaction that occurs across the distribution area of the drug, and there is some influence on hepatic elimination and excretion via the kidney. The metabolization of THD in our bodies is minimally done by CYP450, and 2C19 is engaged in the synthesis process of 5-OH metabolites [160]. In liver microsomes, THD was found to suppress CYP2C19 function while increasing the activity of CYP3A, which means the elevation of CYP3A is due to a heterotopic interactivity rise in CYP3A5. In animal trials, THD revealed a possibility of human CYP3A up-regulation with a greater midazolam clearance with midazolam usage as a pharmacological probe. Based on a recent study, THD acts as a ligand for the pregnane X receptor (PXR) and the constitutive androstane receptor CAR, increasing the activity of the CYP450 enzyme. Since in vitro studies indicated that THD needs CYP450 metabolic stimulation, and that metabolites are detectable in urine, weak metabolizers of CYP2C19 (about 15% of Asians and 25% of Caucasians) may need greater THD dosages. Extensive metabolizers may be at a high risk of side effects. As a result, the CYP2C19 genotype and the CYP2C19 inhibitors or inducers could influence exposure to the active metabolite of THD [161]. Furthermore, adverse effects of THD on the central nervous system CNS, including dizziness, sleepiness, and focusing problems, may be exacerbated by alcohol intake while using THD. Some patients may also have difficulty concentrating and making decisions. While using THD, patients must abstain from or minimize their alcohol use. They should not exceed the prescribed dosage, and refrain from engaging in tasks requiring wakefulness, such as driving or working with dangerous equipment [162]. Figure 4 represents some of adverse effects of THD drug interactions.

Figure 4.

Adverse effects of thalidomide interactions with other drugs may lead to an increased risk of infection, thrombosis, oral mucositis, neurological toxicities, severe bone marrow depression, or increases in the sedative effect of other central nervous system depressants. Furthermore, olopatadine intranasal increases the risk of central nervous system depression, which leads to additive impairment of psychomotor performance, and causes daytime impairment [163,164,165].

9. Conclusions

GBM is still one of the most life-threatening types of primary malignant brain tumors, with a poor prognosis and a low 5-year survival rate. Investigating the different mechanisms of action of THD could lead to new potential uses for the drug, especially when combined with other medications. Future research on treatment options should also consider existing drugs that have different mechanisms for fighting tumors. Additionally, more efforts are needed to develop accurate preclinical models to evaluate treatments’ effectiveness and improve methods for the early diagnosis of GBM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.K. and M.A.; investigation, E.H., H.H., H.K.F., A.W.M.J., A.K.M., N.M.A.-d., S.E., E.G.A.-E., A.M.K., A.A.A., A.I.E., A.A.O. and M.A.; data Curation, E.H., H.H., H.K.F., A.W.M.J., A.K.M., N.M.A.-d. and M.A.; writing—original draft; E.H., H.H., H.K.F., A.W.M.J., A.K.M., N.M.A.-d., S.E., E.G.A.-E., A.A.A., A.I.E., A.A.O. and M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A. and M.K.-Ł.; visualization, E.G.A.-E. and M.A.; supervision, S.E., M.A., A.M.K. and M.K.-Ł.; project administration, M.A. and M.K.-Ł. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Alhassan Ali Ahmed and Mohamed Abouzid are participants of the STER Internationalization of Doctoral Schools Program from the NAWA Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange No. PPI/STE/2020/1/00014/DEC/02. The graphical abstract, Figure 1 and Figure 3, were created with BioRender.com, accessed on 1 February 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Explanation |

| 5-ALA | 5-aminolaevulinic acid |

| ACVRL1 | activin A receptor like type 1 |

| ALA-PDT | 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy |

| ALDH | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 |

| AML | acute myeloid leukemia |

| ATRX | alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation, X-linked |

| AZA | 5-azacytidine |

| AZN | azathioprine |

| bFGF | basic fibroblast growth factors |

| BSA | body surface area |

| CD | cluster of differentiation |

| CIAP2 | cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2 |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| Cox2 | cyclooxygenase 2 |

| CRBN | cereblon |

| DLE | discoid lupus erythematosus |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DTH | delayed-type hypersensitivity |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ENG | endoglin |

| ENL | erythema nodosum leprosum |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| FCT | fludarabine, carboplatin, and topotecan |

| FGF | fibroblast growth factors |

| GBM | glioblastoma multiforme |

| GIB | gastrointestinal bleeding |

| GSCs | glioblastoma stem cells |

| HbF | fetal hemoglobin |

| HHT | hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia |

| HIF | hypoxia-inducible factors |

| HIMEC | human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells |

| HSA | hemangiosarcoma |

| IBD | inflammatory bowel disease |

| IDH | isocitrate dehydrogenases |

| IFN | interferon |

| IFNγ | interferon-gamma |

| IL | interleukin |

| IPF | idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| KCNMA1 | calcium-activated potassium channel subunit alpha-1 |

| LVAD | left ventricular assist device |

| MDR1 | multidrug resistance mutation 1 |

| MDS | myelodysplastic syndrome |

| MDSCs | myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MGMT | O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase |

| MMAC1 | mutated in multiple advanced cancers |

| MVD | marrow microvascular density |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-kappa B |

| NKG2D | natural killer cell activation receptor |

| NSCLC | non-small-cell lung cancer |

| ORR | objective response rate |

| OS | overall survival |

| PASI | psoriasis area and severity index |

| PBMCs | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PDAI | pemphigus disease area index |

| PDGFRA | platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha |

| PDGFRβ | platelet-derived growth factor B |

| PNP | paraneoplastic pemphigus |

| POEMS | (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal protein, skin changes) |

| PPD | purified protein derivative |

| PTEN | phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| PV | pemphigus vulgaris |

| RAS | recurrent aphthous stomatitis |

| RCC | renal cell carcinoma |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| TENM1 | teneurin transmembrane protein 1 |

| TERT | telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| TGF | transforming growth factor |

| TGFβ | transforming growth factor-beta |

| THD | thalidomide |

| TICs | tumor-initiating cells |

| TMZ | temozolomide |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| TNFα | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| Treg | regulatory T |

| VAD | vincristine, liposomal doxorubicin, and dexamethasone |

| VDT | Velcade, Doxil, and thalidomide |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VHL | von Hippel Lindau |

References

- Thakkar, J.P.; Dolecek, T.A.; Horbinski, C.; Ostrom, Q.T.; Lightner, D.D.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Villano, J.L. Epidemiologic and Molecular Prognostic Review of Glioblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 1985–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.C.; Ashley, D.M.; López, G.Y.; Malinzak, M.; Friedman, H.S.; Khasraw, M. Management of glioblastoma: State of the art and future directions. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.; Romão, L.; Martins, S.; Alves, T.; Mendes, F.A.; de Faria, G.P.; Hollanda, R.; Takiya, C.; Chimelli, L.; Morandi, V.; et al. Interactive properties of human glioblastoma cells with brain neurons in culture and neuronal modulation of glial laminin organization. Differentiation 2006, 74, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, K.M.; Jordan, J.T.; Wen, P.Y.; Rosenthal, M.A.; Reardon, D.A. Bevacizumab and glioblastoma: Scientific review, newly reported updates, and ongoing controversies. Cancer 2015, 121, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plate, K.H.; Breier, G.; Weich, H.A.; Risau, W. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a potential tumour angiogenesis factor in human gliomas in vivo. Nature 1992, 359, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vredenburgh, J.J.; Desjardins, A.; Herndon, J.E.; Dowell, J.M.; Reardon, D.A.; Quinn, J.A.; Rich, J.N.; Sathornsumetee, S.; Gururangan, S.; Wagner, M.; et al. Phase II Trial of Bevacizumab and Irinotecan in Recurrent Malignant Glioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Li, B.; Winer, J.; Armanini, M.; Gillett, N.; Phillips, H.S.; Ferrara, N. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis suppresses tumour growth in vivo. Nature 1993, 362, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.L.; Ragel, B.T.; Whang, K.; Gillespie, D. Inhibition of hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) decreases vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion and tumor growth in malignant gliomas. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2006, 78, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.S.; Prados, M.D.; Wen, P.Y.; Mikkelsen, T.; Schiff, D.; Abrey, L.E.; Yung, W.K.A.; Paleologos, N.; Nicholas, M.K.; Jensen, R.; et al. Bevacizumab Alone and in Combination With Irinotecan in Recurrent Glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4733–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Huang, S.; Wang, Z. A meta-analysis of bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in the treatment of patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 19, 1636–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vredenburgh, J.J.; Desjardins, A.; Herndon, J.E.; Marcello, J.; Reardon, D.A.; Quinn, J.A.; Rich, J.N.; Sathornsumetee, S.; Gururangan, S.; Sampson, J.; et al. Bevacizumab Plus Irinotecan in Recurrent Glioblastoma Multiforme. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4722–4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, S.B.; Zarrinmayeh, H.; Das, S.K.; Pollok, K.E.; Vannier, M.W.; Veronesi, M.C. Novel therapeutics and drug-delivery approaches in the modulation of glioblastoma stem cell resistance. Ther. Deliv. 2022, 13, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S.M.B.; Staicu, G.-A.; Sevastre, A.-S.; Baloi, C.; Ciubotaru, V.; Dricu, A.; Tataranu, L.G. Glioblastoma Stem Cells—Useful Tools in the Battle against Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xing, D.; Zhao, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. The Role of a Single Angiogenesis Inhibitor in the Treatment of Recurrent Glioblastoma Multiforme: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, O.G.; Brzozowski, J.S.; Skelding, K.A. Glioblastoma Multiforme: An Overview of Emerging Therapeutic Targets. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadiankia, N. In vitro and in vivo studies of cancer cell behavior under nutrient deprivation. Cell Biol. Int. 2020, 44, 1588–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.; Monteleone, F.; Zambrano, N.; Bianco, R. In Vitro and In Vivo Models for Analysis of Resistance to Anticancer Molecular Therapies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, H.; Reis, R.M.; Nakamura, M.; Colella, S.; Yonekawa, Y.; Kleihues, P.; Ohgaki, H. Loss of Heterozygosity on Chromosome 10 Is More Extensive in Primary (De Novo) Than in Secondary Glioblastomas. Lab. Investig. 2000, 80, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgaki, H.; Kleihues, P. Genetic Pathways to Primary and Secondary Glioblastoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balss, J.; Meyer, J.; Mueller, W.; Korshunov, A.; Hartmann, C.; von Deimling, A. Analysis of the IDH1 codon 132 mutation in brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 116, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobusawa, S.; Watanabe, T.; Kleihues, P.; Ohgaki, H. IDH1 Mutations as Molecular Signature and Predictive Factor of Secondary Glioblastomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 6002–6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Nobusawa, S.; Kleihues, P.; Ohgaki, H. IDH1 Mutations Are Early Events in the Development of Astrocytomas and Oligodendrogliomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Parsons, D.W.; Jin, G.; McLendon, R.; Rasheed, B.A.; Yuan, W.; Kos, I.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Jones, S.; Riggins, G.J.; et al. IDH1andIDH2Mutations in Gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Tachibana, O.; Sato, K.; Yonekawa, Y.; Kleihues, P.; Ohgaki, H. Overexpression of the EGF Receptor and p53 Mutations are Mutually Exclusive in the Evolution of Primary and Secondary Glioblastomas. Brain Pathol. 1996, 6, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgaki, H.; Kleihues, P. The Definition of Primary and Secondary Glioblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegi, M.E.; Diserens, A.-C.; Gorlia, T.; Hamou, M.-F.; de Tribolet, N.; Weller, M.; Kros, J.M.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Mason, W.; Mariani, L.; et al. MGMTGene Silencing and Benefit from Temozolomide in Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, L.A.; Greten, T.F.; Korangy, F. Immune Suppression: The Hallmark of Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells. Immunol. Investig. 2012, 41, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, M.; Cao, X. Cancer-Expanded Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Induce Anergy of NK Cells through Membrane-Bound TGF-β1. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, M.K.; Sinha, P.; Clements, V.K.; Rodriguez, P.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Inhibit T-Cell Activation by Depleting Cystine and Cysteine. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldron, T.J.; Quatromoni, J.G.; Karakasheva, T.A.; Singhal, S.; Rustgi, A.K. Myeloid derived suppressor cells. OncoImmunology 2014, 2, e24117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripodo, C.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X.; Zhu, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, G.; Yuan, X. The Role of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Patients with Solid Tumors: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serocki, M.; Bartoszewska, S.; Janaszak-Jasiecka, A.; Ochocka, R.J.; Collawn, J.F.; Bartoszewski, R. miRNAs regulate the HIF switch during hypoxia: A novel therapeutic target. Angiogenesis 2018, 21, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Li, X.; Jia, Y.-f.; Piazza, G.A.; Xi, Y. Hypoxia-regulated microRNAs in human cancer. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balamurugan, K. HIF-1 at the crossroads of hypoxia, inflammation, and cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, N.; Ratcliffe, P.J. Hypoxia signaling pathways in cancer metabolism: The importance of co-selecting interconnected physiological pathways. Cancer Metab. 2014, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldogazieva, N.T.; Mokhosoev, I.M.; Terentiev, A.A. Metabolic Heterogeneity of Cancer Cells: An Interplay between HIF-1, GLUTs, and AMPK. Cancers 2020, 12, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, D.; Semenza, G.L. Metabolic adaptation of cancer and immune cells mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Rev. Cancer 2018, 1870, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Physiology and Medicine. Cell 2012, 148, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Khwaja, F.W.; Severson, E.A.; Matheny, S.L.; Brat, D.J.; Van Meir, E.G. Hypoxia and the hypoxia-inducible-factor pathway in glioma growth and angiogenesis. Neuro-Oncology 2005, 7, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wang, J.-J.; Fu, X.-L.; Guang, R.; To, S.-S.T. Advances in the targeting of HIF-1α and future therapeutic strategies for glioblastoma multiforme. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiche, J.; Brahimi-Horn, M.C.; Pouysségur, J. Tumour hypoxia induces a metabolic shift causing acidosis: A common feature in cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 771–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Gillies, R.J. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerweck, L.E.; Seetharaman, K. Cellular pH gradient in tumor versus normal tissue: Potential exploitation for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kallinowski, F.; Vaupel, P. pH distributions in spontaneous and isotransplanted rat tumours. Br. J. Cancer 1988, 58, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaupel, P.; Kallinowski, F.; Okunieff, P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: A review. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 6449–6465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hjelmeland, A.B.; Wu, Q.; Heddleston, J.M.; Choudhary, G.S.; MacSwords, J.; Lathia, J.D.; McLendon, R.; Lindner, D.; Sloan, A.; Rich, J.N. Acidic stress promotes a glioma stem cell phenotype. Cell Death Differ. 2010, 18, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K. Acidic Extracellular pH Induces Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in Human Glioblastoma Cells via ERK1/2 MAPK Signaling Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 11368–11374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukumura, D.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Gohongi, T.; Seed, B.; Jain, R.K. Hypoxia and acidosis independently up-regulate vascular endothelial growth factor transcription in brain tumors in vivo. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 6020–6024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mekhail, K.; Gunaratnam, L.; Bonicalzi, M.-E.; Lee, S. HIF activation by pH-dependent nucleolar sequestration of VHL. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Bao, S.; Wu, Q.; Wang, H.; Eyler, C.; Sathornsumetee, S.; Shi, Q.; Cao, Y.; Lathia, J.; McLendon, R.E.; et al. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors Regulate Tumorigenic Capacity of Glioma Stem Cells. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J.V.; Conroy, S.; Pavlov, K.; Sontakke, P.; Tomar, T.; Eggens-Meijer, E.; Balasubramaniyan, V.; Wagemakers, M.; den Dunnen, W.F.A.; Kruyt, F.A.E. Hypoxia enhances migration and invasion in glioblastoma by promoting a mesenchymal shift mediated by the HIF1α–ZEB1 axis. Cancer Lett. 2015, 359, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peppino, G.; Ruiu, R.; Arigoni, M.; Riccardo, F.; Iacoviello, A.; Barutello, G.; Quaglino, E. Teneurins: Role in Cancer and Potential Role as Diagnostic Biomarkers and Targets for Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.; Corvalán, A.; Roa, I.; Brañes, J.A.; Wollscheid, B. Teneurin protein family: An emerging role in human tumorigenesis and drug resistance. Cancer Lett. 2012, 326, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcelen, M.; Velasquez, C.; Vidal, V.; Gutiérrez, O.; Fernández-Luna, J.L. Signaling Pathways Regulating the Expression of the Glioblastoma Invasion Factor TENM1. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heddleston, J.M.; Li, Z.; McLendon, R.E.; Hjelmeland, A.B.; Rich, J.N. The hypoxic microenvironment maintains glioblastoma stem cells and promotes reprogramming towards a cancer stem cell phenotype. Cell Cycle 2014, 8, 3274–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, S.; Garvalov, B.K.; Wirta, V.; von Stechow, L.; Schänzer, A.; Meletis, K.; Wolter, M.; Sommerlad, D.; Henze, A.-T.; Nistér, M.; et al. A hypoxic niche regulates glioblastoma stem cells through hypoxia inducible factor 2α. Brain 2010, 133, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeda, A.; Park, M.; Lee, D.; Mintz, A.; Androutsellis-Theotokis, A.; McKay, R.D.; Engh, J.; Iwama, T.; Kunisada, T.; Kassam, A.B.; et al. Hypoxia promotes expansion of the CD133-positive glioma stem cells through activation of HIF-1α. Oncogene 2009, 28, 3949–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevet, E.; Hetz, C.; Samali, A. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress—Activated Cell Reprogramming in Oncogenesis. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetz, C.; Zhang, K.; Kaufman, R.J. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakes, S.A. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling in Cancer Cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2020, 190, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, E.; Logue, S.E.; Healy, S.J.; Manie, S.; Samali, A. The role of the unfolded protein response in cancer progression: From oncogenesis to chemoresistance. Biol. Cell 2019, 111, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheloni, G.; Poteti, M.; Bono, S.; Masala, E.; Mazure, N.M.; Rovida, E.; Lulli, M.; Dello Sbarba, P. The Leukemic Stem Cell Niche: Adaptation to “Hypoxia” versus Oncogene Addiction. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 4979474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovida, E.; Peppicelli, S.; Bono, S.; Bianchini, F.; Tusa, I.; Cheloni, G.; Marzi, I.; Cipolleschi, M.G.; Calorini, L.; Sbarba, P.D. The metabolically-modulated stem cell niche: A dynamic scenario regulating cancer cell phenotype and resistance to therapy. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 3169–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comerford, K.M.; Wallace, T.J.; Karhausen, J.; Louis, N.A.; Montalto, M.C.; Colgan, S.P. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent regulation of the multidrug resistance (MDR1) gene. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 3387–3394. [Google Scholar]

- Doublier, S.; Belisario, D.C.; Polimeni, M.; Annaratone, L.; Riganti, C.; Allia, E.; Ghigo, D.; Bosia, A.; Sapino, A. HIF-1 activation induces doxorubicin resistance in MCF7 3-D spheroids via P-glycoprotein expression: A potential model of the chemo-resistance of invasive micropapillary carcinoma of the breast. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yan, Q.; Liao, B.; Zhao, L.; Xiong, S.; Wang, J.; Zou, D.; Pan, J.; Wu, L.; Deng, Y.; et al. The HIF1α/HIF2α-miR210-3p network regulates glioblastoma cell proliferation, dedifferentiation and chemoresistance through EGF under hypoxic conditions. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-H.; Ma, Z.-X.; Huang, G.-H.; Xu, Q.-F.; Xiang, Y.; Li, N.; Sidlauskas, K.; Zhang, E.E.; Lv, S.-Q. Downregulation of HIF-1a sensitizes U251 glioma cells to the temozolomide (TMZ) treatment. Exp. Cell Res. 2016, 343, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatsuma-Okumura, T.; Ito, T.; Handa, H. Molecular Mechanisms of the Teratogenic Effects of Thalidomide. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faver, I.R.; Guerra, S.G.; Su, W.P.D.; el-Azhary, R. Thalidomide for dermatology: A review of clinical uses and adverse effects. Int. J. Dermatol. 2005, 44, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazato, K.; Tahara, H.; Hayakawa, Y. Antimetastatic effects of thalidomide by inducing the functional maturation of peripheral natural killer cells. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 2770–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, C.M.; Araújo e Silva, A.C.; de Jesus Ferraciolli, C.; Moreira, G.V.; Campos, L.C.; dos Reis, D.C.; Lopes, M.T.P.; Ferreira, M.A.N.D.; Andrade, S.P.; Cassali, G.D. Combination therapy with carboplatin and thalidomide suppresses tumor growth and metastasis in 4T1 murine breast cancer model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2014, 68, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, Y.; Ishida, T. Immunomodulatory drugs in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 49, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, S.A.; McCarthy, P.L. Immunomodulatory Drugs in Multiple Myeloma: Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Experience. Drugs 2017, 77, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Handa, H. Molecular mechanisms of thalidomide and its derivatives. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 2020, 96, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargesson, N. Thalidomide-induced teratogenesis: History and mechanisms. Birth Defects Res. Part C Embryo Today Rev. 2015, 105, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.J.; Pucilowska, J.; Lombardi, R.Q.; Rooney, J.P. A mutation in a novel ATP-dependent Lon protease gene in a kindred with mild mental retardation. Neurology 2004, 63, 1927–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angers, S.; Li, T.; Yi, X.; MacCoss, M.J.; Moon, R.T.; Zheng, N. Molecular architecture and assembly of the DDB1–CUL4A ubiquitin ligase machinery. Nature 2006, 443, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.J.; Hao, J.; Kosofsky, B.E.; Rajadhyaksha, A.M. Dysregulation of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel expression in nonsyndromal mental retardation due to a cereblon p.R419X mutation. Neurogenetics 2008, 9, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.; Lee, K.-H.; Song, S.; Jung, Y.-K.; Park, C.-S. Identification and functional characterization of cereblon as a binding protein for large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 2005, 94, 1212–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Scialli, A.R. Thalidomide: The Tragedy of Birth Defects and the Effective Treatment of Disease. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 122, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reske, T.; Fulciniti, M.; Munshi, N.C. Mechanism of action of immunomodulatory agents in multiple myeloma. Med. Oncol. 2010, 27, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zervas, K.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Hatzicharissi, E.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Papaioannou, M.; Mitsouli, C.; Panagiotidis, P.; Korantzis, J.; Tzilianos, M.; Maniatis, A. Primary treatment of multiple myeloma with thalidomide, vincristine, liposomal doxorubicin and dexamethasone(T-VAD doxil): A phase II multicenter study. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Mehdi, M.; Mumtaz, M.; Ali, F.; Lascher, S.; Galili, N. Combination of 5-azacytidine and thalidomide for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2008, 113, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesari, S.; Schiff, D.; Henson, J.W.; Muzikansky, A.; Gigas, D.C.; Doherty, L.; Batchelor, T.T.; Longtine, J.A.; Ligon, K.L.; Weaver, S.; et al. Phase II study of temozolomide, thalidomide, and celecoxib for newly diagnosed glioblastoma in adults. Neuro-Oncology 2008, 10, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Giralt, S.; Delasalle, K.; Handy, B.; Alexanian, R. Bortezomib in combination with thalidomide-dexamethasone for previously untreated multiple myeloma. Hematology 2013, 12, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, R.J.; Morgan, M.; Rawat, A. Phase I/II study of thalidomide in combination with interleukin-2 in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2006, 106, 1498–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, P.; Fu, P.; Lazarus, H.; Kane, D.; Meyerson, H.; Hartman, P.; Reyes, R.; Creger, R.; Stear, K.; Laughlin, M.; et al. Antiangiogenic activity of thalidomide in combination with fludarabine, carboplatin, and topotecan for high-risk acute myelogenous leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2009, 48, 1940–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanovic, D.; Sticht, C.; Röhrich, M.; Maier, P.; Grosu, A.-L.; Herskind, C. Inhibition of 13-cis retinoic acid-induced gene expression of reactive-resistance genes by thalidomide in glioblastoma tumoursin vivo. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 28938–28948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Flores, P.N.; Barraza-Reyna, P.J.; Aguirre-Vázquez, A.; Camacho-Moll, M.E.; Guerrero-Beltrán, C.E.; Resendez-Pérez, D.; González-Villasana, V.; Garza-González, J.N.; Silva-Ramírez, B.; Castorena-Torres, F.; et al. Isotretinoin and Thalidomide Down-Regulate c-MYC Gene Expression and Modify Proteins Associated with Cancer in Hepatic Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, A.S.; Mahida, Y.R.; Clarke, D.; Ryder, S.D.; Freeman, J.G. A pilot study to investigate the use of oxpentifylline (pentoxifylline) and thalidomide in portal hypertension secondary to alcoholic cirrhosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, L.G.; Haslett, P.; Maartens, G.; Steyn, L.; Kaplan, G. Thalidomide-Induced Antigen-Specific Immune Stimulation in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 and Tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 181, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, J.P.; Orbell, G.; Cave, N.; Munday, J.S. Does thalidomide prolong survival in dogs with splenic haemangiosarcoma? J. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 59, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casseb, J.; Fonseca, L.A.M.; Veiga, A.P.R.; de Almeida, A.; Bueno, A.; Ferez, A.C.; Gonsalez, C.R.; Brigido, L.F.M.; Mendonça, M.; Rodrigues, R.; et al. AIDS Incidence and Mortality in a Hospital-Based Cohort of HIV-1–Seropositive Patients Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy in São Paulo, Brazil. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2003, 17, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Pan, L.; Du, G.; Yao, H.; Tang, G. A Randomized controlled clinical trial on dose optimization of thalidomide in maintenance treatment for recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2021, 51, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, S.; Solé, C.; Moliné, T.; Ferrer, B.; Ordi-Ros, J.; Cortés-Hernández, J. Efficacy of Thalidomide in Discoid Lupus Erythematosus: Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms. Dermatology 2020, 236, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhu, B.; Ye, H.; Zhang, W.; Guan, J.; Su, K. Thalidomide for Epistaxis in Patients with Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: A Preliminary Study. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2017, 157, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F. Thalidomide for the Control of Severe Paraneoplastic Pruritus Associated With Hodgkin’s Disease. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2010, 27, 486–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, E.R.; Kaplin, A.I.; Kerr, D.A. Thalidomide for acute treatment of neurosarcoidosis. Spinal Cord 2007, 45, 802–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harte, M.C.; Saunsbury, T.A.; Hodgson, T.A. Thalidomide use in the management of oromucosal disease: A 10-year review of safety and efficacy in 12 patients. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2020, 130, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Mao, R.; Chen, F.; Xu, P.-P.; Chen, B.-L.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, S.-H.; Feng, R.; Zeng, Z.-R.; et al. Thalidomide induces clinical remission and mucosal healing in adults with active Crohn’s disease: A prospective open-label study. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2017, 10, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropff, M.; Baylon, H.G.; Hillengass, J.; Robak, T.; Hajek, R.; Liebisch, P.; Goranov, S.; Hulin, C.; Blade, J.; Caravita, T.; et al. Thalidomide versus dexamethasone for the treatment of relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma: Results from OPTIMUM, a randomized trial. Haematologica 2011, 97, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, H.M.; Nahm, F.S.; Lim, Y.J.; Park, J.H.; Kim, C.S. The effect of thalidomide on spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion injury in a rabbit model. Spinal Cord 2006, 45, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Matsui, O. The antiangiogenic effect of thalidomide on occult liver metastases: Anin vivostudy in mice. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 24, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, S.; Sato, Y.; Katayama, K.; Nagashima, K.; Aoyagi, R.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Sobue, G.; Koike, H.; Yabe, I.; Sasaki, H.; et al. Safety and efficacy of thalidomide in patients with POEMS syndrome: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purev, U.; Chung, M.J.; Oh, D.-H. Individual differences on immunostimulatory activity of raw and black garlic extract in human primary immune cells. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2012, 34, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.; Mills, M.; Cantwell, M.M.; Cardwell, C.R.; Murray, L.J.; Donnelly, M. Thalidomide for managing cancer cachexia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2021, CD008664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, B.J.J.; Teo, L.L.Y.; Chan, L.L.; Sim, D.K.L.; Kerk, K.L.; Soon, J.L.; Tan, T.E.; Sivathasan, C.; Lim, C.P. Novel Use of Low-dose Thalidomide in Refractory Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Left Ventricular Assist Device Patients. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2017, 40, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Mehta, J.; Desikan, R.; Ayers, D.; Roberson, P.; Eddlemon, P.; Munshi, N.; Anaissie, E.; Wilson, C.; Dhodapkar, M.; et al. Antitumor Activity of Thalidomide in Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1565–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tramontana, J.M.; Utaipat, U.; Molloy, A.; Akarasewi, P.; Burroughs, M.; Makonkawkeyoon, S.; Johnson, B.; Klausner, J.D.; Rom, W.; Kaplan, G. Thalidomide Treatment Reduces Tumor Necrosis Factor α Production and Enhances Weight Gain in Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Mol. Med. 1995, 1, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, E.; Ardic, N.; Sürücü, H.A.; Aksoy, M.; Satoskar, A.R.; Varikuti, S.; Doni, N.; Oghumu, S.; Yesilova, A.; Yeşilova, Y. A Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Syrian and Turkish Patients with Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 93, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusa, M.G.; Pearce, D.; Camacho, F.; Willard, J.; McCarty, A.; Feldman, S.R. An Open-Label Trial of Thalidomide in the Treatment of Chronic Plaque Psoriasis. Psoriasis Forum 2018, 15a, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, T.R.C.; Samer, S.; Santos-Oliveira, J.R.; Giron, L.B.; Arif, M.S.; Silva-Freitas, M.L.; Cherman, L.A.; Treitsman, M.S.; Chebabo, A.; Sucupira, M.C.A.; et al. Thalidomide is Associated With Increased T Cell Activation and Inflammation in Antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected Individuals in a Randomised Clinical Trial of Efficacy and Safety. EBioMedicine 2017, 23, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, M. Thalidomide as a potential adjuvant treatment for paraneoplastic pemphigus: A single-center experience. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Mao, X.; Zhao, W.; Jin, H.; Li, L. Successful treatment with thalidomide for pemphigus vulgaris. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2020, 11, 2040622320916023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.Y.; Han, Y.J.; Im, J.H.; Baek, J.H.; Lee, J.S. Two cases of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV patients treated with thalidomide. Int. J. STD AIDS 2019, 30, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.K. Medicine. How thalidomide works against cancer. Science 2014, 343, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou, V.; Bamias, A.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Thalidomide in cancer medicine. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, P.; Hideshima, T.; Anderson, K. Thalidomide: Emerging role in cancer medicine. Annu. Rev. Med. 2002, 53, 629–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morabito, A.; Fanelli, M.; Carillio, G.; Gattuso, D.; Sarmiento, R.; Gasparini, G. Thalidomide prolongs disease stabilization after conventional therapy in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Oncol. Rep. 2004, 11, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, G.M.; Pavlakis, N.; McCowatt, S.; Boyle, F.M.; Levi, J.A.; Bell, D.R.; Cook, R.; Biggs, M.; Little, N.; Wheeler, H.R. Phase II study of thalidomide in the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). J. Neuro-Oncol. 2001, 54, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, H.A.; Figg, W.D.; Jaeckle, K.; Wen, P.Y.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Loeffler, J.S.; Levin, V.A.; Black, P.M.; Kaplan, R.; Pluda, J.M.; et al. Phase II Trial of the Antiangiogenic Agent Thalidomide in Patients With Recurrent High-Grade Gliomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadul, C.E.; Kingman, L.S.; Meyer, L.P.; Cole, B.F.; Eskey, C.J.; Rhodes, C.H.; Roberts, D.W.; Newton, H.B.; Pipas, J.M. A phase II study of thalidomide and irinotecan for treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2008, 90, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puduvalli, V.K.; Giglio, P.; Groves, M.D.; Hess, K.R.; Gilbert, M.R.; Mahankali, S.; Jackson, E.F.; Levin, V.A.; Conrad, C.A.; Hsu, S.H.; et al. Phase II trial of irinotecan and thalidomide in adults with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-Oncology 2008, 10, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, B.M.; Wang, M.; Yung, W.K.A.; Fine, H.A.; Donahue, B.A.; Tremont, I.W.; Richards, R.S.; Kerlin, K.J.; Hartford, A.C.; Curran, W.J.; et al. A phase II study of conventional radiation therapy and thalidomide for supratentorial, newly-diagnosed glioblastoma (RTOG 9806). J. Neuro-Oncol. 2012, 111, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.M.; Lamborn, K.R.; Malec, M.; Larson, D.; Wara, W.; Sneed, P.; Rabbitt, J.; Page, M.; Nicholas, M.K.; Prados, M.D. Phase II study of temozolomide and thalidomide with radiation therapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 60, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, F.M.; Lassman, A.B. Factorial clinical trials: A new approach to phase II neuro-oncology studies. Neuro-Oncology 2014, 17, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanovic, D.; Maier, P.; Schanne, D.H.; Wenz, F.; Herskind, C. The influence of retinoic Acid and thalidomide on the radiosensitivity of u343 glioblastoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar]

- Penas-Prado, M.; Hess, K.R.; Fisch, M.J.; Lagrone, L.W.; Groves, M.D.; Levin, V.A.; De Groot, J.F.; Puduvalli, V.K.; Colman, H.; Volas-Redd, G.; et al. Randomized phase II adjuvant factorial study of dose-dense temozolomide alone and in combination with isotretinoin, celecoxib, and/or thalidomide for glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2015, 17, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, M.; Imbesi, F.; Beghi, E.; Galli, C.; Citterio, A.; Trapani, P.; Sterzi, R.; Collice, M. Temozolomide and thalidomide in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Anticancer Res. 2007, 27, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hassler, M.R.; Sax, C.; Flechl, B.; Ackerl, M.; Preusser, M.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Woehrer, A.; Dieckmann, K.U.; Rössler, K.; Prayer, D.; et al. Thalidomide as Palliative Treatment in Patients with Advanced Secondary Glioblastoma. Oncology 2015, 88, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, X.; Song, Z.; Jian, H.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Lu, S. Pyrotinib combined with thalidomide in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients harboring HER2 exon 20 insertions (PRIDE): Protocol of an open-label, single-arm phase II trial. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanan-Khan, A.; Miller, K.C. Velcade, Doxil and Thalidomide (VDT) is an effective salvage regimen for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2009, 46, 1103–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Qi, F.; Shi, K.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Pan, J.; Zhou, T.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Thalidomide combined with low-dose short-term glucocorticoid in the treatment of critical Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020, 10, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.E.; Hall, M.C.; Miller, A.; Ridenhour, K.P.; Stindt, D.; Lovato, J.F.; Patton, S.E.; Brinkley, W.; Das, S.; Torti, F.M. Phase II trial of combination interferon-alpha and thalidomide as first-line therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urology 2004, 63, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emre, S.; Sumrani, N.; Hong, J. Beneficial Effect of Thalidomide and Ciclosporin Combination in Heterotopic Cardiac Transplantation in Rats. Eur. Surg. Res. 1990, 22, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, P.; Dhamne, M.; Hess, K.R.; Gilbert, M.R.; Groves, M.D.; Levin, V.A.; Kang, S.L.; Ictech, S.E.; Liu, V.; Colman, H.; et al. Phase 2 trial of irinotecan and thalidomide in adults with recurrent anaplastic glioma. Cancer 2012, 118, 3599–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.; Dahlberg, S.E.; Schiller, J.H.; Mehta, M.P.; Fitzgerald, T.J.; Belinsky, S.A.; Johnson, D.H. Randomized Phase III Study of Thoracic Radiation in Combination With Paclitaxel and Carboplatin With or Without Thalidomide in Patients With Stage III Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: The ECOG 3598 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Rudd, R.; Woll, P.J.; Ottensmeier, C.; Gilligan, D.; Price, A.; Spiro, S.; Gower, N.; Jitlal, M.; Hackshaw, A. Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Thalidomide in Combination With Gemcitabine and Carboplatin in Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5248–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Qiu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhuang, X.; Huang, S.; Li, M.; Feng, R.; Chen, B.; He, Y.; Zeng, Z.; et al. Thalidomide Combined With Azathioprine as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Azathioprine-Refractory Crohn’s Disease Patients. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 557986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Han, Z.; Wang, X.; Mo, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, A.; Liu, S. Combination therapy of infliximab and thalidomide for refractory entero-Behcet’s disease: A case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollum, A.D.; Wu, B.; Clark, J.W.; Kulke, M.H.; Enzinger, P.C.; Ryan, D.P.; Earle, C.C.; Michelini, A.; Fuchs, C.S. The Combination of Capecitabine and Thalidomide in Previously Treated, Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 29, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, R.; Chen, L.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yin, Q.; Wei, X. Combined use of interferon alpha-1b, interleukin-2, and thalidomide to reverse the AML1-ETO fusion gene in acute myeloid leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 2021, 100, 2593–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mita, M.M.; Rowinsky, E.K.; Forero, L.; Eckhart, S.G.; Izbicka, E.; Weiss, G.R.; Beeram, M.; Mita, A.C.; de Bono, J.S.; Tolcher, A.W.; et al. A phase II, pharmacokinetic, and biologic study of semaxanib and thalidomide in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2006, 59, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.-M.; Gulley, J.L.; Arlen, P.M.; Woo, S.; Steinberg, S.M.; Wright, J.J.; Parnes, H.L.; Trepel, J.B.; Lee, M.-J.; Kim, Y.S.; et al. Phase II Trial of Bevacizumab, Thalidomide, Docetaxel, and Prednisone in Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2070–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladini, G.; Perfetti, V.; Perlini, S.; Obici, L.; Lavatelli, F.; Caccialanza, R.; Invernizzi, R.; Comotti, B.; Merlini, G. The combination of thalidomide and intermediate-dose dexamethasone is an effective but toxic treatment for patients with primary amyloidosis (AL). Blood 2005, 105, 2949–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, J.M.; Majumdar, S.K. Antitumorigenic Evaluation of Thalidomide Alone and in Combination with Cisplatin in DBA2/J Mice. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2002, 2, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Sheth, R.; Shah, K.; Patel, K. Safety and effectiveness of thalidomide and hydroxyurea combination in β-thalassaemia intermedia and major: A retrospective pilot study. Br. J. Haematol. 2019, 188, e18–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsenova, L.; Sokol, K.; Victoria, H.F.; Kaplan, G. A Combination of Thalidomide plus Antibiotics Protects Rabbits from Mycobacterial Meningitis-Associated Death. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 177, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallet, S.; Palumbo, A.; Raje, N.; Boccadoro, M.; Anderson, K.C. Thalidomide and lenalidomide: Mechanism-based potential drug combinations. Leuk. Lymphoma 2009, 49, 1238–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zduniak, K.; Gdesz-Birula, K.; Woźniak, M.; Duś-Szachniewicz, K.; Ziółkowski, P. The Assessment of the Combined Treatment of 5-ALA Mediated Photodynamic Therapy and Thalidomide on 4T1 Breast Carcinoma and 2H11 Endothelial Cell Line. Molecules 2020, 25, 5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Fu, L. Effect of thalidomide combined with TP chemotherapy on serum VEGF and NRP-1 levels advanced esophageal cancer patients. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 10809–10815. [Google Scholar]

- Ghobrial, I.M.; Rajkumar, S.V. Management of thalidomide toxicity. J. Support. Oncol. 2003, 1, 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.; Case, D.; Enevold, G.; Rosdhal, R.; Tatter, S.B.; Ellis, T.L.; McQuellon, R.P.; McMullen, K.P.; Stieber, V.W.; Shaw, E.G.; et al. A phase II trial of thalidomide and procarbazine in adult patients with recurrent or progressive malignant gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 2012, 106, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou, V. Adverse effects of thalidomide administration in patients with neoplastic diseases. Am. J. Med. 2004, 117, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, J.K.; Uppal, G.; Raina, V. The adverse effects of thalidomide in relapsed and refractory patients of multiple myeloma. Ann. Oncol. 2002, 13, 1636–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, T.; Bjorkman, S.; Hoglund, P. Clinical pharmacology of thalidomide. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 57, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morival, C.; Oumari, S.; Lenglet, A.; Le Corre, P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of oral drugs in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 36, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherbet, G.V. Therapeutic Potential of Thalidomide and Its Analogues in the Treatment of Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 5767–5772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baxter, K.; Preston, C.L. (Eds.) Stockley’s Drug Interactions, 9th ed.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thalidomide (Rx) Interactions. Available online: https://reference.medscape.com/drug/thalomid-thalidomide-343211#3 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Thalidomide Drug Interactions. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/thalidomide-index.html?filter=3 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).