Black Holes: Eliminating Information or Illuminating New Physics?

Abstract

:1. Being Simple is Complex

1.1. If You Can Heat It, It Has Micro-Structure!

1.2. Beginner’s Information Loss

2. The Way It All Began

2.1. Semi-Classical Information Loss

- It is not only about horizon: Hiding is not destroyingTill now we have obtained that at the future times an observer will feel to be set up in thermal setting had she started with a vacuum state. However, this really does not amount to saying the black holes do radiate. Masking off a portion of initial vacuum data can be brought about by any horizon, even by the Rindler horizon at the least (or the de Sitter horizon). Therefore, even in Minkowski space time, such horizons can exist which mask off a portion of the vacuum field configuration from a specified family of observers. This does not amount to say that even Minkowski spacetimes radiate. They do not! There is no real flux of radiation in Minkowski spacetime, precisely because it is homogeneous, isotropic and time translational symmetric.What the horizons are capable of, is to give rise to thermal environment for a special set of observers measuring real flux of radiation. The genesis of radiation is brought about by breaking some of the symmetries the spacetime possess, and this is the story of a black hole.

- It is also about geometry non-trivia:The main difference a black hole has from the other horizon settings we commented above is that the black hole not only breaks the homogeneity due to curvature, it also breaks time reversal invariance in order to give rise to time irreversible phenomenon like radiation. In fact the sitting in Equation (4) is understood to be total time, such that particle creation rate per unit time becomes exactly that of a radiating body. Thus, it is the breaking of these symmetries which allow the flux of energy radiated away to be non zero [59,60] when calculated from . Thus, non trivial geometry of the spacetime added with the presence of horizon makes the black hole radiate thermally (predominantly). This is the point exactly where we make true contact with the thermodynamics of the black hole we kept believing in (even when a concrete proof was not available), and this, unfortunately, is also exactly where the problem at hand starts unfolding.

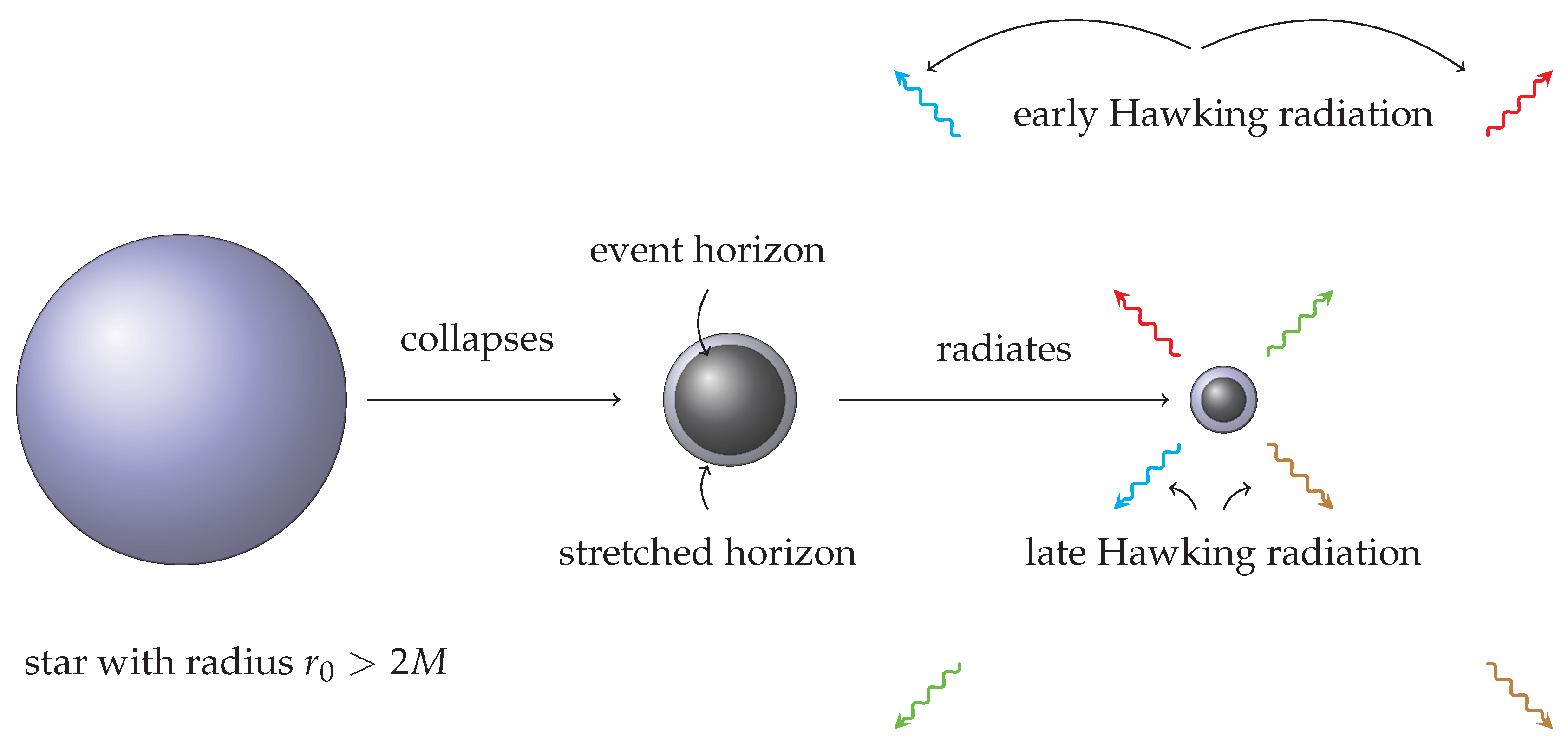

- ... and about finiteness of size:Now that we have credible theoretical understanding that the black holes leak out energy in thermal flux, we can think of the black hole losing mass in this way and evaporating away in time. We did not require anything extra than our belief in the quantum field theory on a regular manifold (however curved it may be). Therefore, unless the black hole becomes so small where the differential structure of spacetime is no longer applicable, we do not see any other reason to discredit or mistrust our calculations (for the case of primordial black holes, see [61,62,63]). This, then immediately leads us to expect that being compact and hence finite sized, the black holes evaporate away practically completely. Then there is a crisis at our hands!

2.2. The Paradox

3. Hiding Information in Correlations

3.1. The Black Hole History

3.2. No Hiding Theorem—No Information in Correlations between Separable Hilbert Spaces

4. Black Hole Complementarity

4.1. Posing The Problem

4.2. A Possible Resolution

- Formation and evaporation of black hole, viewed by a distant observer can be described entirely using unitary quantum mechanics.

- Outside stretched horizon, semi-classical physics holds good.

- To a distant observer, the black hole is a quantum system with discrete energy levels and number of states being exponential of Bekenstein entropy.

4.3. Problem with These Postulates: Firewall?

4.4. The Role of In-Falling Vacuum

4.5. The Problem of Projection Operator: Can Firewall Exist?

5. The Overreach of Quantum Gravity

5.1. The Fuzzball Paradigm

5.1.1. The No No-Hair!

5.1.2. Violation of Semi-Classical Approximation

5.1.3. Free fall: Fuzzball Complementarity

5.2. A Stable and a Proportionate Remnant?

- One bound on the size of the remnant can be found from appealing to the maximum compressibility of information in a given region. Giddings [112] argued that if there exists an upper bound on entropy density, it should better be that of a Planck scale sized remnant, i.e.,Now, once some matter enters a macroscopic black hole horizon, it inevitably gets drifted towards the central spacelike singularity. Classically all such matter would ultimately reach the central singularity, making it also an infinite entropy density place. However, since we have already committed that the maximum entropy density should always be given by Equation (36), it is reasonable to expect that a quantum theory of gravity, respecting the entropy bound will replace the central singularity by a region of maximum entropy density. The size of the region of such a maximum entropy density corresponding to a black hole of mass M would beThis depicts the region of a core where the entropy of mass M black hole is stored with the maximum capacity. However the fact that the spacetime behind event horizon is not static is in tension with the concept of a core. To remove the spacelike singularity one needs to introduce additional matter fields modifying the “going to be” singular point within the spacelike region. This possibly requires the core to have some non-trivial matter fields, e.g., non-linear electrodynamics may be one viable candidate [113].From Equation (37), it is clear that the size of the core scales with the initial data (aka the mass). Once the black hole starts evaporating, the event horizon starts shrinking. However, since the core is packed with the maximum density allowed, it does not have a capacity to further accommodate any bits carrying the information of evaporation14. Thus, while the horizon shrinks, the core persists. Therefore, there will come a stage when the horizon meets the core and then the Hawking process loses its credibility. What happens next is up for speculation as it caters to regime of Planck scale physics, which we hardly have any clue of (note that the entropy density is at the Planck scale, while the physical size can still be macroscopic). There can be a plethora of various exotic possible outcomes when the horizon comes crashing down to the Planck density core, which has replaced the classical singularity [114]. It can also be thought that the gravity shows some phase transition at this leg of evaporation, and end up in some sort of crystal as a leftover remnant [115]. It is well known that once systems undergo a phase transition into a crystalline phase, quantum correlations become pretty long range. Therefore, it is possible that effects of quantum gravity, in the similar spirit, become important even at large length scales leading to a mass proportionate remnant. Either we need to know the physics inside these remnants or we will have to further wait for the time scale which a remnant of this kind lives for, before jumping back to the revival of (or declaring a convincing triumph over) the problem of information loss.

- In canonical splitting of gravity, we end up with various constraints on the variables of the theory, we use to describe the same. These constraints appear as operator equations at the quantum level, if we keep using these variables in quantum gravity. Using the method of discretization of spacetime lattice [116], one can argue that the solution space, consistent with diffeomorphism constraints, with positive frequency, is obtained through states of the kindrepresenting a collapsing shell marked as i, with giving its proper time, being its area radius (in the case of spherically symmetric collapse) at proper time and is related to the mass function of the shell. a and b are functions of . Now, vanishing of determines the location of the apparent horizon, classically. So the classical location of the apparent horizon () serves as a point where the wave functional in Equation (38) develops a discontinuous behavior15. The argument of the exponential has a discontinuous (by an amount of residue at the pole) across the “apparent horizon”. Moreover for a particular branch (i.e., with choosing one sign of the ± in the exponent), we see that the directions of the shells across the horizons are opposite.Using this approach of canonical quantization, it can be argued [116] that any collapse of matter in the exterior of the apparent horizon of the collapsing data is accompanied by an out going radiation in the interior of the apparent horizon (and vice versa)16[116]. It is further argued [117,118] that, the absence of firewall must require that only one branch of solutions exists, i.e., a collapsing shell in the exterior accompanied by a thermal radiation in the interior. There should not be any branch that has a collapsing shell in the interior accompanied by a Hawking radiation in the exterior. Therefore, the profile of mass distribution of the shell should be such that its collapse is effectively counterbalanced and gets supported by the interior thermal radiation. Such a mass profile, the size of a resulting “stable structure” and its relation to gravitational mass of the cloud is estimated for different cases [118,119]. Therefore, in this scenario, the collapse halts at the apparent horizon and the black hole never forms in the first place. All what is left is a dust cloud-ball hinging at the apparent horizon, as a stable remnant, being supported by a radiation pressure from the inside necessitated by quantum gravity. This cloud-ball also hides in its inside, a negative mass singularity which gives rise to the radiation flux in the interior.

6. The Quantum Framework: A Re-Look Required(?)

6.1. Can Non-Locality Save the Day?

6.1.1. ER=EPR

6.1.2. Bargaining Micro-Causality: State-Dependent Operators

6.1.3. A Final State for Black Holes

6.2. Bargaining Unitarity: Modifications of Quantum Physics

- Output of a measurementThe standard quantum theory we are familiar with tells us that the time evolution of a closed system is unitary in nature,where H is the Hamiltonian of the system. However, when a measurement is done on such system, it collapses into one of the eigenstates corresponding to the observable being measured, i.e.,with being one of the eigenstates . Therefore, such a process is seemingly non-unitary and information destroying (Once a measurement is done and the system “collapses” to one of the eigenstates, information is destroyed, about what is was before the measurement is done). The system evolves unitarily between measurements but measurement itself is a seemingly non unitary process. Although it is also a debatable point of view [152,153,154,155,156] and the debate and discussion is quite hot on this. So if we subscribe to the idea that measurement itself is a non unitary process, we should also reflect on what is so special about a measurement process. In a measurement process a quantum system interacts with an apparatus (which itself is a collection of many small quantum systems) and collapses. So, it looks like the combined system of (quantum system + apparatus) is effectively a collection of large number of quantum systems which evolves non unitarily! This prompted the proponents of non unitary quantum theory to say that quantum mechanics fundamentally should be non-unitary in nature, with non-unitarity becomes apparent only when the number of degrees of freedom becomes very large [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. A system with small number of degrees of freedom has a dynamics which is very well approximated by a unitary theory. In that sense protecting information does not remain a principle of nature any more, but only an effective feature when the number of degrees of freedom in the system is very small. A macroscopic black hole, which has very large number of degrees of freedom (as suggested by its entropy) is a fit case where such non-unitarity, if present, should be visible.

- A single copy of a closed systemAnother possible explanation of measurement process can come through the idea of decoherence. If we consider only a subsystem of a large system, the effective dynamics of the subsystem may be non unitary such that the evolution of the full system is still unitary. Also making many copies of subsystem, we can make sense of a statistical interpretation of quantum theory. However, this becomes a problem when we look at a closed system, which has only a single realization. In this case, we have neither system-subsystem division nor many copies of this system to apply statistical description. Therefore, the quantum theory, as it is, fails to give any deterministic prediction. Problem becomes more prominent if such a system evolves on its own to a classical description. Then we are really in a fix. This is a setting where quantum theory is not designed to be applied upon. Our universe makes a concrete example of such a system. Thus, non-unitary modifications to quantum theory derives motivation also from quantum cosmology [157,158,159,160,161,162,163].

6.2.1. How Much of Non-Unitarity in Quantum Mechanics is Tolerable ?

6.2.2. Continuous Spontaneous Localization Evolution of the Quantum State

7. Black Holes Have (Soft) Hairs

7.1. Supertranslation

7.2. Lorentz Transformation and Superrotation

7.3. Soft Photon Hair on Black Holes: An Illustration

8. A Simple Way to Extract Information—Non-Vacuum Distortions

8.1. Hard (Quantum) Hairs on Black Holes?

8.2. Information of Black Hole Formation: Correlation Function

8.3. Radiation from Black Hole: Information about the Initial State

9. Information Regain?

9.1. Late Time Flash

- Between the initial and final bits radiated, the information about the in-fallen matter is effectively deleted from each individual subsystem (interior or early or late time radiation considered individually).

- Prior to bits are radiated (for any positive ) the information of infalling matter resides in the interior only with fidelity .

- It is in only the final bits (for any positive ), the information is imprinted in the late time radiation considered separately with fidelity .

9.2. Old Enough Black Hole Behaves as a “Mirror”

10. Black Hole Scattering Matrix

11. What Have We Learnt?

- Initial belief was that a black hole is no different than a black body and after a certain time (Page time), i.e., when the Hilbert spaces of the early Hawking radiation and the remaining black hole have similar dimensionality the information starts leaking out of the hole [70]. This view was challenged by the no-hiding theorem of Brustein et al., [71] where they showed that there exists virtually no information in the correlations of a bipartite system. It was subsequently realized that black hole can actually be thought as a tripartite system, and this tripartite system can have correlations storing information. However, then one can ask the question, which of these correlations have the full information of what has fallen in the black hole. It turns out the attempt to answer this challenge leads to the complementarity proposal [209].

- In the complementarity proposal, one assumes that the same copy of information is present both for the static and infalling observer, but since none of them can access the both the copies, there is no violation of the no-cloning theorem. This virtually reduces the no-cloning theorem, for a single causal patch. For the static observer the information is assumed to be stored in a stretched horizon, Planck length away from the hole, while for the infalling observer the information is residing inside the horizon. However the above scenario invites the firewall puzzle. Since the region near the stretched horizon is entangled with both black hole interior and the early Hawking radiation, thus violating the strong sub-additivity of entropy. Whether a freely falling observer has sufficient time before she crosses the horizon to do quantum computation to realize this violation remains a debated subject as of now. One possible resolution being breakdown of equivalence principle, resulting in a non-vacuum structure at the horizon—the firewall [77].

- There have been numerous works, both supporting and opposing the firewall argument. Many have agreed on the violation of strong sub-additivity of entropy, but suggesting some third alternative rather than leaving equivalence principle or quantum theory at stake. There have also been claims that the firewall argument is wrong—possibly it does not describe a classical world. Till now no unique consensus has been reached.

- A very straightforward plausible resolution of the information puzzle is to suggest that the black holes themselves do not exist. This seemingly is the case in the context of certain string theory approach, leading to the fuzzball paradigm [56]. According to this picture, there is no spacetime region inside the event horizon, instead the spacetime caps off through compactified extra dimensions and the resulting curvature acts as a proxy for the gravitating mass. Then evaporation of black holes becomes exactly like burning of coal (nothing separated by causal curtain) and as a result, there is no paradox. As of future, one might want to study the geometry of a fuzzball state, and see if there is any deviation from the Schwarzschild solution. Such a modification have to confront the solar system tests and many more, which the general relativity allowed geometries have done successfully. It will be interesting to see, what the fuzzball paradigm has to offer when the horizons have no tussle with quantum theory. For example, it would be interesting to see what happens for other horizons in general relativity (e.g., Rindler horizon, de Sitter horizon) because they also hide information and have entropy so as to give rise to large number of microscopic configurations. There are also other ideas [112,115,118] which call for a drastic changes to the classical understanding of black holes to fight the information loss they seemingly cause. A geometric study of the fuzzball may provide further insight of such objects.

- Non-local character of quantum correlations can also play a very crucial role towards resolving both the information paradox and the firewall puzzle. Quantum correlations, themselves, are not constrained by causality and spill over from the interior part as well. One may postulate that any two systems, which have quantum correlations (like EPR correlations) are connected by an wormhole like structure in spacetime, famously known as Einstein-Rosen bridge. Thus, the early and late Hawking quanta are connected by ER bridge and hence can exchange information. Also the existence of firewall depends on the static observer, who is playing with the early Hawking radiation. If she decides to decipher the correlations in the early Hawking radiation, the infalling observer will experience firewall, otherwise it will be a smooth transition through the horizon. It would be interesting if one can arrive at an estimate of the probability for existence of a firewall from such an approach. Further, the traversibility of such wormholes must also be properly accounted for.

- In order to describe the black hole interior using local bulk operators in the AdS/CFT correspondence, it seems essential for the mapping of CFT operators corresponding to the bulk, to depend on the state of the quantum field in CFT. This also leads to an explicit realization of complementarity, where operators in two causally disconnected regions are related to each other. These state dependent operators lead to violation of micro-causality, i.e., commutator between operators inside and outside the event horizon vanishes for low point correlation but not for high point ones. The above realization of complementarity was performed in the context of empty AdS, it would be interesting to investigate the situation for more general setups with non-maximal symmetric cases. Moreover, the loss of micro-causality at high point correlations should be thoroughly investigated. Whether there is any signature of violation of such micro-locality can transcend down to visible scales is an interesting topic of research.

- One can also, though very reluctantly, think of giving up unitarity, which is the main point of tussle between black hole and the quantum theory. One has to tackle this situation with extreme care, since then one has to confront the very successful unitary quantum theory as well. However it turns out that there exist two features which are not well explained in the context of standard quantum theory—(a) the measurement process, resulting in collapse of wave function itself appears non-unitary and (b) the probabilistic interpretation fails when we have a single copy of a closed system, e.g., the universe as a whole. Till date, the attempts to obtain a consistent non-unitary theory explaining the quantum world have yielded a single non-unitary and non-relativistic generalization, known as the Continuous Spontaneous Localization theory with a stochastic, classical source field driving the quantum system helping in collapse of the wave function. A variation of this model when applied to evaporating black hole results in collapse of the wave function to a number eigenstate, such that the resultant density matrix is thermal. Thus, in this picture one has a thermal radiation and loss of information, but there is nothing paradoxical as fit for a standard quantum system, where measurement leads to collapse of the wave function. Clearly, a thorough understanding of quantum theory, particularly when we move towards larger systems, will help settling out this issue. More so over, if a modification on this account is indeed required, relativistic version of that modified theory must first be sought for, before we can tune such modifications in the black hole setting.

- It has been more or less an agreed upon stance that in unitarily evaporating black hole, most of the information comes very late in time and comes out as a flash. In fact, calculations also show that once the black hole enters the “revealing phase” it literally becomes incapable of holding anything which is then thrown in. Therefore, after a certain time it actually adapts the blackbody character of radiation.

- As advocated recently, in the semi-classical and the quantum domain the no-hair theorems fail and black holes do have additional hairs, storing information about what has fallen into the hole. There can be hairs due to non-vacuum character of the matter fallen in, leading to non-vacuum characters of quantum correlations and also there can be soft hairs, due to infinitely many diffeomorphisms the horizon can afford. The non-vacuum hairs encode the departure of the in-fallen state to be different from the vacuum state. Whenever a matter field carry non-zero stress energy into the black hole, that clearly gets reflected in its late time frequency correlation. With added information of the initial symmetry of the in-data, it is even possible to fully reconstruct the state. A detailed analysis from the point of quantum teleportation and availability of classical channels, particularly at low energies, is definitely required.

- The soft hairs originate due an infinite number of degenerate vacuum states with the same energy but differing in the existence of additional soft photons or gravitons. These are the Goldstone bosons originating from additional symmetries at the black hole horizon, similar to the supertranslations and superrotations for the asymptotically flat spacetimes. The conservation of charges associated with these symmetries following the soft graviton theorem of Weinberg leads to these infinitely inequivalent vacuum states. Understanding of these symmetries and the resulting soft quanta for an arbitrary null surface (of which the black hole horizon is a special case) could be a very insightful exercise for progress.

- One can also invoke more subtle effects to recover the information thrown in the black hole. One such possibility being the Aichelburg-Sexl boost, in which a test particle is dragged along the trajectory of a passing by photon and the displacement suffered depends on the energy of the photon. This shows that as a particle falls into the black hole, it drags the outgoing Hawking quanta along it and hence pass over the information to the quanta, resulting in recovery of information fallen into the hole.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Derivation of Supertranslation Diffeomorphism

Appendix B. Lorentz Transformation at Infinity

Appendix C. The Structure of Superrotation

Appendix D. Coherent (Like) States with Compact Correlation Support

References

- Adler, S.L. Generalized quantum dynamics. Nucl. Phys. B 1994, 415, 195–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. A Suggested interpretation of the quantum theory in terms of hidden variables. 1. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. A Suggested interpretation of the quantum theory in terms of hidden variables. 2. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diosi, L. A Universal Master Equation for the Gravitational Violation of Quantum Mechanics. Phys. Lett. A 1987, 120, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, H. Relative state formulation of quantum mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1957, 29, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, A.; Lochan, K.; Satin, S.; Singh, T.P.; Ulbricht, H. Models of Wave-function Collapse, Underlying Theories, and Experimental Tests. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013, 85, 471–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, A.; Ghirardi, G.C. Dynamical reduction models. Phys. Rept. 2003, 379, 257–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Breakdown of Predictability in Gravitational Collapse. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 2460–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, R.M. Gravitational collapse and cosmic censorship. In Black Holes, Gravitational Radiation and the Universe; Iyer, B.R., Bhawal, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 1997; Volume 100, pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, P.S. Cosmic Censorship: A Current Perspective. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2002, 17, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hod, S. Weak Cosmic Censorship: As Strong as Ever. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, A.I.M.; Goswami, R.; Maharaj, S.D. Cosmic Censorship Conjecture revisited: Covariantly. Class. Quantum Gravity 2014, 31, 135010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation, 3rd ed.; W. H. Freeman and Company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S.W.; Ellis, G.F.R. The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time; Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S.W.; Israel, W. General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, T. Gravitation: Foundations and Frontiers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhanov, V.; Winitzki, S. Introduction to Quantum Effects in Gravity, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Poisson, E. A Relativist’s Toolkit: The Mathematics of Black-Hole Mechanics, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, R.M. General Relativity, 1st ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Birrell, N.D.; Davies, P.C.W. Quantum Fields in Curved Space; Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, L.E.; Toms, D. Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime; Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, A.; Navarro-Salas, J. Modeling Black Hole Evaporation; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fulling, S.A. Aspects of Quantum Field Theory in Curved Space-time. Lond. Math. Soc. Stud. Texts 1989, 17, 1–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Generalized second law of thermodynamics in black hole physics. Phys. Rev. D 1974, 9, 3292–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.M.; Carter, B.; Hawking, S.W. The Four laws of black hole mechanics. Commun. Math. Phys. 1973, 31, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.W.; Hawking, S.W. Cosmological Event Horizons, Thermodynamics, and Particle Creation. Phys. Rev. D 1977, 15, 2738–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Black Holes and Thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 13, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and the second law. Lett. Nuovo Cim. 1972, 4, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle Creation by Black Holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of space-time: The Einstein equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan, T. Gravity and the thermodynamics of horizons. Phys. Rept. 2005, 406, 49–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Thermodynamical Aspects of Gravity: New insights. Rept. Prog. Phys. 2010, 73, 046901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. General Relativity from a Thermodynamic Perspective. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2014, 46, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Padmanabhan, T. Thermodynamical interpretation of the geometrical variables associated with null surfaces. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 92, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Parattu, K.; Padmanabhan, T. Gravitational field equations near an arbitrary null surface expressed as a thermodynamic identity. J. High Energy Phys. 2015, 2015, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Padmanabhan, T. Evolution of Spacetime arises due to the departure from Holographic Equipartition in all Lanczos-Lovelock Theories of Gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 124017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S. Lanczos-Lovelock gravity from a thermodynamic perspective. J. High Energy Phys. 2015, 2015, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. The Atoms Of Space, Gravity and the Cosmological Constant. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2016, 25, 1630020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Gravity and/is Thermodynamics. Curr. Sci. 2015, 109, 2236–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Distribution function of the Atoms of Spacetime and the Nature of Gravity. Entropy 2015, 17, 7420–7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Padmanabhan, T. Entropy of a generic null surface from its associated Virasoro algebra. Phys. Lett. B 2016, 763, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, E. Classical Black Holes Are Hot. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1408.3691. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, S.D. The Information paradox: A Pedagogical introduction. Class. Quantum Gravity 2009, 26, 224001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, D. Jerusalem Lectures on Black Holes and Quantum Information. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polchinski, J. The Black Hole Information Problem. In Proceedings of the Theoretical Advanced Study Institute in Elementary Particle Physics: New Frontiers in Fields and Strings (TASI 2015), Boulder, CO, USA, 1–26 June 2015; pp. 353–397. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S. Black hole explosions. Nature 1974, 248, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.; Hawking, S. Action Integrals and Partition Functions in Quantum Gravity. Phys. Rev. D 1977, 15, 2752–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R.B. The Firewall Phenomenon. Fundam. Theor. Phys. 2015, 178, 71–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer, C. Hawking radiation from decoherence. Class. Quantum Gravity 2001, 18, L151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers, J.G.; Kiefer, C. Decoherence of black holes by Hawking radiation. Phys. Rev. D 1996, 53, 7050–7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Susskind, L. Cool horizons for entangled black holes. Fortsch. Phys. 2013, 61, 781–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M. Thermality of the Hawking flux. J. Hihg Energy Phys. 2015, 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Serrano, A.; Visser, M. On burning a lump of coal. Phys. Lett. B 2016, 757, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Serrano, A.; Visser, M. Entropy/information flux in Hawking radiation. arXiv, 2015; arXiv:1512.01890. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, S.D. Tunneling into fuzzball states. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2010, 42, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadodimas, K.; Raju, S. Black Hole Interior in the Holographic Correspondence and the Information Paradox. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 051301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modak, S.K.; Ortíz, L.; Peña, I.; Sudarsky, D. Non-Paradoxical Loss of Information in Black Hole Evaporation in a Quantum Collapse Model. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 124009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Singh, S.; Padmanabhan, T. A quantum peek inside the black hole event horizon. J. High Energy Phys. 2015, 2015, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chakraborty, S. Black hole kinematics: The “in”-vacuum energy density and flux for different observers. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 024011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlopov, M.Yu. Primordial Black Holes. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2010, 10, 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlopov, M.Y.; Barrau, A.; Grain, J. Gravitino production by primordial black hole evaporation and constraints on the inhomogeneity of the early universe. Class. Quantum Gravity 2006, 23, 1875–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlopov, M.; Malomed, B.A.; Zeldovich, I.B. Gravitational instability of scalar fields and formation of primordial black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1985, 215, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, F.; Schuster, S.; Van–Brunt, A.; Visser, M. The Hawking cascade from a black hole is extremely sparse. Class. Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 115003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hod, S. Discrete black hole radiation and the information loss paradox. Phys. Lett. A 2002, 299, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hod, S. Gravitation, the quantum, and Bohr’s correspondence principle. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 1999, 31, 1639–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Lochan, K. Quantum leaps of black holes: Magnifying glasses of quantum gravity. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2016, 25, 1644024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochan, K.; Chakraborty, S. Discrete quantum spectrum of black holes. Phys. Lett. B 2016, 755, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, A.; Stojkovic, D. Radiation from a collapsing object is manifestly unitary. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 111301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, D.N. Information in black hole radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 3743–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braunstein, S.L.; Pati, A.K. Quantum information cannot be completely hidden in correlations: Implications for the black-hole information paradox. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 080502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braunstein, S.L.; Van Loock, P. Quantum information with continuous variables. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005, 77, 513–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, S.L.; Pirandola, S.; Życzkowski, K. Better Late than Never: Information Retrieval from Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 101301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; Parker, L.; Peleg, Y. Predictability and semiclassical approximation at the onset of black hole formation. Phys. Rev. D 1996, 54, 7490–7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, D.S.; Nho, D.; Oh, J.; Park, H.; Yeom, D.h.; Zoe, H. Page curves for tripartite systems. Class. Quantum Gravity 2017, 34, 145004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L.; Thorlacius, L.; Uglum, J. The Stretched horizon and black hole complementarity. Phys. Rev. D 1993, 48, 3743–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Black Holes: Complementarity or Firewalls? J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.G.; Wald, R.M. On evolution laws taking pure states to mixed states in quantum field theory. Phys. Rev. D 1995, 52, 2176–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, D.H.; Zoe, H. Semi-classical black holes with large N re-scaling and information loss problem. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2011, 26, 3287–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.H.; Thorne, K.S. Membrane Viewpoint on Black Holes: Properties and Evolution of the Stretched Horizon. Phys. Rev. D 1986, 33, 915–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, M.K. Membrane Horizons: The Black Hole’s New Clothes. Ph.D. Thesis, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bousso, R. Complementarity Is Not Enough. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 124023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, S.G.; Chowdhury, B.D.; Puhm, A. Unitarity and fuzzball complementarity: ’Alice fuzzes but may not even know it!’. J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, B.D.; Puhm, A. Is Alice burning or fuzzing? Phys. Rev. D 2013, 88, 063509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D.; Turton, D. The flaw in the firewall argument. Nucl. Phys. B 2014, 884, 566–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Stanford, D.; Sully, J. An Apologia for Firewalls. J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Yeom, D.H. Status report: black hole complementarity controversy. Nucl. Phys. Proc. Suppl. 2014, 246–247, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, D.; Hayden, P. Quantum Computation vs. Firewalls. J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. Firewalls from double purity. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 88, 084035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadodimas, K.; Raju, S. An Infalling Observer in AdS/CFT. J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Varela, J.; Weinberg, S.J. Black Holes, Information, and Hilbert Space for Quantum Gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 084050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. The Transfer of Entanglement: The Case for Firewalls. arXiv, 2012; arXiv:1210.2098. [Google Scholar]

- Brustein, R. Origin of the blackhole information paradox. Fortsch. Phys. 2014, 62, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giveon, A.; Itzhaki, N. String Theory Versus Black Hole Complementarity. J. High Energy Phys. 2012, 2012, 094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenker, S.H.; Stanford, D. Black holes and the butterfly effect. J. High Energy Phys. 2014, 2014, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooft, G.T. The firewall transformation for black holes and some of its implications. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1612.08640. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, Y.C.; McInnes, B.; Chen, P. Cold black holes in the Harlow–Hayden approach to firewalls. Nucl. Phys. B 2015, 891, 627–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.; Stojkovic, D. Icezones instead of firewalls: extended entanglement beyond the event horizon and unitary evaporation of a black hole. Class. Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 135006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. What prevents gravitational collapse in string theory? Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2016, 25, 1644018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. Remnants, Fuzzballs or Wormholes? Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2014, 23, 1442024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. Fuzzballs and the information paradox: A Summary and conjectures. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2009, 2, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. The Fuzzball proposal for black holes: An Elementary review. Fortsch. Phys. 2005, 53, 793–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strominger, A.; Vafa, C. Microscopic origin of the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy. Phys. Lett. B 1996, 379, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. Emission rates, the correspondence principle and the information paradox. Nucl. Phys. B 1998, 529, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunin, O.; Mathur, S.D. Statistical interpretation of Bekenstein entropy for systems with a stretched horizon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 211303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, P.; Mathur, S.D. Nature abhors a horizon. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2015, 24, 1543003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.W.; Warner, N.P. Global structure of five-dimensional fuzzballs. Class. Quantum Gravity 2014, 31, 025016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ong, Y.C.; Page, D.N.; Sasaki, M.; Yeom, D.H. Naked Black Hole Firewalls. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 161304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, S.D.; Plumberg, C.J. Correlations in Hawking radiation and the infall problem. J. High Energy Phys. 2011, 2011, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. Black Holes and Beyond. Ann. Phys. 2012, 327, 2760–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, B.D.; Mathur, S.D. Radiation from the non-extremal fuzzball. Class. Quantum Gravity 2008, 25, 135005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, S.B. Black holes and massive remnants. Phys. Rev. D 1992, 46, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ong, Y.C.; Yeom, D.H. Black Hole Remnants and the Information Loss Paradox. Phys. Rept. 2015, 603, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharonov, Y.; Casher, A.; Nussinov, S. The Unitarity Puzzle and Planck Mass Stable Particles. Phys. Lett. B 1987, 191, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, H. Gravitational crystal inside the black hole. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2015, 30, 1550201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, C.; Lochan, K. Tunneling during quantum collapse in AdS spacetime. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 024045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, C. Black holes as Gravitational Atoms. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2014, 23, 1441002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, C. Quantum gravitational dust collapse does not result in a black hole. Nucl. Phys. B 2015, 891, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Vaz, C.; Wijewardhana, L.C.R. Quantum dust collapse in 2+1 dimension. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 043017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, A.; Stojkovic, D. Nonlocal (but also nonsingular) physics at the last stages of gravitational collapse. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 89, 044003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, E.; Stojkovic, D. Quantum gravitational collapse: Non-singularity and non-locality. J. High Energy Phys. 2008, 2008, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.; Lochan, K.; Narasimha, D. Gravitational lensing by self-dual black holes in loop quantum gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; SenGupta, S. Strong gravitational lensing—A probe for extra dimensions and Kalb-Ramond field. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1611.06936. [Google Scholar]

- Ramallo, A.V. Introduction to the AdS/CFT correspondence. Springer Proc. Phys. 2015, 161, 411–474. [Google Scholar]

- Maldacena, J.M. The Large N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1999, 38, 1113–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Anti-de Sitter space and holography. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1998, 2, 253–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharony, O.; Gubser, S.S.; Maldacena, J.M.; Ooguri, H.; Oz, Y. Large N field theories, string theory and gravity. Phys. Rept. 2000, 323, 183–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnoll, S.A. Lectures on holographic methods for condensed matter physics. Class. Quantum Gravity 2009, 26, 224002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hoker, E.; Freedman, D.Z. Supersymmetric gauge theories and the AdS/CFT correspondence. In Proceedings of the TASI Strings, Branes and Extra Dimensions, Boulder, CO, USA, 4–29 June 2001; pp. 3–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev, S. Condensed Matter and AdS/CFT. In From Gravity to Thermal Gauge Theories: The AdS/CFT Correspondence; Papantonopoulos, E., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 828, pp. 273–311. [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka, T.; Ryu, S.; Takayanagi, T. Holographic Entanglement Entropy: An Overview. J. Phys. A 2009, 42, 504008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can quantum mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Phys. Rev. 1935, 47, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Rosen, N. The Particle Problem in the General Theory of Relativity. Phys. Rev. 1935, 48, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.W.; Wheeler, J.A. Causality and Multiply Connected Space-Time. Phys. Rev. 1962, 128, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M. Lorentzian Wormholes: From Einstein to Hawking; American Institute of Physics: Melville, New York, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marolf, D.; Wall, A.C. Eternal Black Holes and Superselection in AdS/CFT. Class. Quantum Gravity 2013, 30, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, W. Thermo field dynamics of black holes. Phys. Lett. A 1976, 57, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.M. Eternal black holes in anti-de Sitter. J. High Energy Phys. 2003, 2003, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, K.L.H.; Medved, A.J.M. Black holes and information: A new take on an old paradox. Adv. High Energy Phys. 2017, 2017, 7578462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misner, C.W.; Wheeler, J.A. Classical physics as geometry: Gravitation, electromagnetism, unquantized charge, and mass as properties of curved empty space. Ann. Phys. 1957, 2, 525–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wu, C.H.; Yeom, D.h. Broken bridges: A counter-example of the ER=EPR conjecture. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2017, 2017, 040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadodimas, K.; Raju, S. State-Dependent Bulk-Boundary Maps and Black Hole Complementarity. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 89, 086010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadodimas, K.; Raju, S. Remarks on the necessity and implications of state-dependence in the black hole interior. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 084049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadodimas, K.; Raju, S. Local Operators in the Eternal Black Hole. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 211601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Bryan, J.W.; Papadodimas, K.; Raju, S. A toy model of black hole complementarity. J. High Energy Phys. 2016, 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Raju, S. The Breakdown of String Perturbation Theory for Many External Particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 131602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlieder, S. Some remarks about the localization of states in a quantum field theory. Comm. Math. Phys. 1965, 1, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M.; Hartle, J.B. Time symmetry and asymmetry in quantum mechanics and quantum cosmology. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Ion Sources (ICIS 1991), Bensheim, Germany, 30 September–4 October 1991; pp. 1151–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.H.; Brassard, G.; Crepeau, C.; Jozsa, R.; Peres, A.; Wootters, W.K. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 1895–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, G.T.; Maldacena, J.M. The Black hole final state. J. High Energy Phys. 2004, 2004, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, D.; Preskill, J. Comment on ’The Black hole final state’. J. High Energy Phys. 2004, 2004, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D.; Bub, J. A Proposed Solution of the Measurement Problem in Quantum Mechanics by a Hidden Variable Theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1966, 38, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Testing Quantum Mechanics. Ann. Phys. 1989, 194, 336–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Collapse of the State Vector. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 062116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 715–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeh, H.D. On the interpretation of measurement in quantum theory. Found. Phys. 1970, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Sahlmann, H.; Sudarsky, D. On the quantum origin of the seeds of cosmic structure. Class. Quantum Gravity 2006, 23, 2317–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsky, D. Shortcomings in the Understanding of Why Cosmological Perturbations Look Classical. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2011, 20, 509–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañate, P.; Pearle, P.; Sudarsky, D. Continuous spontaneous localization wave function collapse model as a mechanism for the emergence of cosmological asymmetries in inflation. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Vennin, V.; Peter, P. Cosmological Inflation and the Quantum Measurement Problem. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Lochan, K.; Sahu, S.; Singh, T.P. Quantum to classical transition of inflationary perturbations: Continuous spontaneous localization as a possible mechanism. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 88, 085020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon, E.; Sudarsky, D. Benefits of Objective Collapse Models for Cosmology and Quantum Gravity. Found. Phys. 2014, 44, 114–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochan, K.; Parattu, K.; Padmanabhan, T. Quantum Evolution Leading to Classicality: A Concrete Example. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2015, 47, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumulka, R. On spontaneous wave function collapse and quantum field theory. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 2006, 462, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedingham, D.J. Relativistic state reduction dynamics. Found. Phys. 2011, 41, 686–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearle, P. Relativistic dynamical collapse model. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, C.G., Jr.; Giddings, S.B.; Harvey, J.A.; Strominger, A. Evanescent black holes. Phys. Rev. D 1992, 45, R1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, S.B.; Nelson, W.M. Quantum emission from two-dimensional black holes. Phys. Rev. D 1992, 46, 2486–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochan, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Padmanabhan, T. Dynamic realization of the Unruh effect for a geodesic observer. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1603.01964. [Google Scholar]

- Ashtekar, A.; Taveras, V.; Varadarajan, M. Information is Not Lost in the Evaporation of 2D Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 211302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modak, S.K.; Sudarsky, D. Modelling non-paradoxical loss of information in black hole evaporation. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1607.05410. [Google Scholar]

- Okon, E.; Sudarsky, D. Black Holes, Information Loss and the Measurement Problem. Found. Phys. 2017, 47, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedingham, D.; Modak, S.K.; Sudarsky, D. Relativistic collapse dynamics and black hole information loss. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 94, 045009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon, E.; Sudarsky, D. The Black Hole Information Paradox and the Collapse of the Wave Function. Found. Phys. 2015, 45, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, S.K.; Ortíz, L.; Peña, I.; Sudarsky, D. Black hole evaporation: information loss but no paradox. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2015, 47, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W.; Perry, M.J.; Strominger, A. Soft Hair on Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 231301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawking, S.W.; Perry, M.J.; Strominger, A. Superrotation Charge and Supertranslation Hair on Black Holes. J. High Energy Phys. 2017, 2017, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, H.; van der Burg, M.G.J.; Metzner, A.W.K. Gravitational waves in general relativity. 7. Waves from axisymmetric isolated systems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1962, 269, 21–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, R.K. Gravitational waves in general relativity. 8. Waves in asymptotically flat space-times. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1962, 270, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strominger, A. On BMS Invariance of Gravitational Scattering. J. High Energy Phys. 2014, 2014, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Infrared photons and gravitons. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, B516–B524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachazo, F.; Strominger, A. Evidence for a New Soft Graviton Theorem. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1404.4091. [Google Scholar]

- Ashtekar, A.; Hansen, R.O. A unified treatment of null and spatial infinity in general relativity. I-Universal structure, asymptotic symmetries, and conserved quantities at spatial infinity. J. Math. Phys. 1978, 19, 1542–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A. Asymptotic Quantization of the Gravitational Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 46, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulish, P.P.; Faddeev, L.D. Asymptotic conditions and infrared divergences in quantum electrodynamics. Theor. Math. Phys. 1970, 4, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.; Saotome, R.; Akhoury, R. Construction of an asymptotic S matrix for perturbative quantum gravity. J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 159. [Google Scholar]

- Barnich, G.; Troessaert, C. Symmetries of asymptotically flat 4 dimensional spacetimes at null infinity revisited. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 111103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barnich, G.; Troessaert, C. Supertranslations call for superrotations. arXiv, 2011; arXiv:1102.4632. [Google Scholar]

- Barnich, G.; Troessaert, C. BMS charge algebra. J. High Energy Phys. 2011, 2011, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Kapec, D.; Lysov, V.; Pasterski, S.; Strominger, A. Higher-Dimensional Supertranslations and Weinberg’s Soft Graviton Theorem. Ann. Math. Sci. Appl. 2017, 2, 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hollands, S.; Ishibashi, A.; Wald, R.M. BMS Supertranslations and Memory in Four and Higher Dimensions. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1612.03290. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, J.; Solodukhin, S.N. A Holographic reduction of Minkowski space-time. Nucl. Phys. B 2003, 665, 545–593. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, T. A Critique of pure string theory: Heterodox opinions of diverse dimensions. arXiv, 2003; arXiv:0306074. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, P.A. A Spherical impulse gravity wave. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nutku, Y.; Halil, M. Colliding Impulsive Gravitational Waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1977, 39, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, R. The geometry of impulsive gravitational waves. In General Relativity: Papers in Honour of J.L. Synge; O’Raifeartaigh, L., Ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1972; pp. 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Strominger, A.; Zhiboedov, A. Superrotations and Black Hole Pair Creation. Class. Quantum Gravity 2017, 34, 064002. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.; Lysov, V.; Mitra, P.; Strominger, A. BMS supertranslations and Weinberg’s soft graviton theorem. J. High Energy Phys. 2015, 2015, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Parattu, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Majhi, B.R.; Padmanabhan, T. A Boundary Term for the Gravitational Action with Null Boundaries. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2016, 48, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Donnay, L.; Giribet, G.; Gonzalez, H.A.; Pino, M. Supertranslations and Superrotations at the Black Hole Horizon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 091101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compère, G.; Long, J. Classical static final state of collapse with supertranslation memory. Class. Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 195001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, C.; Oz, Y. On the Membrane Paradigm and Spontaneous Breaking of Horizon BMS Symmetries. J. High Energy Phys. 2016, 2016, 065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochan, K.; Padmanabhan, T. Extracting information about the initial state from the black hole radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 051301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochan, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Padmanabhan, T. Information retrieval from black holes. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 94, 044056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochan, K.; Padmanabhan, T. Inertial nonvacuum states viewed from the Rindler frame. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 044002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatwin-Davies, A.; Jermyn, A.S.; Carroll, S.M. How to Recover a Qubit That Has Fallen Into a Black Hole. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 261302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuis, F. The Decoupling Approach to Quantum Information Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ’T Hooft, G. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. arXiv, 1993; arXiv:gr-qc/9310026. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, P.; Preskill, J. Black holes as mirrors: Quantum information in random subsystems. J. High Energy Phys. 2007, 2007, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’T Hooft, G. Diagonalizing the Black Hole Information Retrieval Process. arXiv, 2015; arXiv:1509.01695. [Google Scholar]

- ’T Hooft, G. On the Quantum Structure of a Black Hole. Nucl. Phys. B 1985, 256, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’T Hooft, G. The Scattering matrix approach for the quantum black hole: An Overview. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 1996, 11, 4623–4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’T Hooft, G. Strings From Gravity. Phys. Scripta T 1987, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichelburg, P.C.; Sexl, R.U. On the Gravitational field of a massless particle. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 1971, 2, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, T.; ’t Hooft, G. The Gravitational Shock Wave of a Massless Particle. Nucl. Phys. B 1985, 253, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | This is also referred as no-hair theorems after proving the conjecture in some specialized scenarios |

| 2 | To such observers, the entropy of the black hole may be accounted for as the entanglement entropy. However, whether the black hole thermodynamics is indeed due to the entanglement entropy remains an open issue, since in many alternative gravity theories, the black hole entropy does not scale as area, while the entanglement entropy always does. Thus, whether entanglement entropy is a mirror to the micro-canonical construction of black hole is not entirely evident. |

| 3 | In Quantum Field Theory, we rather talk about mode functions than the particles. |

| 4 | In fact, for a large dimensional system such as a macroscopic black hole, behavior of a specific unitary process is very close to what an average over various unitaries will suggest : Levy’s lemma. |

| 5 | We think of the Hawking radiation as such a mapping. |

| 6 | Ancilla : A (foreknown) quantum state which tags along the main state of study. |

| 7 | In a similar spirit in which, position basis and momenta basis are unitarily related and equally justified for decomposing a state into. |

| 8 | However it was advocated in [78] that the transition from pure state to mix state does not necessarily lead to bizzare consequences for laboratory physics, thereby asserting no information paradox for black holes. |

| 9 | However recently it was demonstrated that if one works with a large number of quantum fields in a black hole background it may be possible to see copied information in tussle with complimentarity, see [79]. |

| 10 | By near horizon regime we imply a spacetime region around every point on the event horizon, where one may neglect the effect of curvature and treat the spacetime to be flat. |

| 11 | Given a spacetime point, one can always expand any metric around the Minkowski background with additional curvature corrections introducing an associated length scale to the problem. If one is interested in physics beyond this length scale, the notion of local inertial physics is no longer applicable. The region B is thought to be living within this length scale. |

| 12 | One requires an Planck scale energy to come out of ’H’. |

| 13 | One can think of a situation where a null shell is collapsing to form a black hole, resulting in formation of event horiozn at earth, due to its teleological property. However one should not expect some quantum gravity effects to become prominent at earth even long before the black hole actually forms. |

| 14 | Recall the core is saturated in sense of entropy! Any additional bit will decrease the mass but increase its entropy, since the information of the mass lost by the radiation has not gone outside, as we deduced in previous sections. |

| 15 | |

| 16 | This is also argued to be a reason of genesis of Hawking radiation through quantum gravity, interior collapse will always be accompanied by an outgoing radiation in the exterior [116]. |

| 17 | This may have some connections with the “charge without charge” proposal of Wheeler [140]. |

| 18 | However as pointed out in [141], one may encounter a situation where the ER bridge, may become traversable hitting the locality of EPR pairs, raising doubts against the genericity of the proposal. |

| 19 | To provide an quantitative estimate regarding the number of spacetime points, one notes that the only non-trivial number associated with this problem is , defined in terms of the AdS length scale in Equation (42). Thus, by large number of points we mean . Similarly two spacetime points will be close enough if the proper distance ℓ between them satisfies . |

| 20 | Evidently, macroscopic systems do not follow quantum mechanics. Whether it is due to decoherence or the breakdown of unitarity is the topic of debate. |

| 21 | In fact is a smeared operator, with the smearing telling us about the resolution of different positions. |

| 22 | Any such symmetry of spacetime which enhances the global symmetry group under consideration are known as large diffeomorphisms. Thus, supertranslation is an example of a large diffeomorphism due to enhancement of global Poincaré symmetry. |

| 23 | This is analogous to the classical channel in the EPR terminology. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chakraborty, S.; Lochan, K. Black Holes: Eliminating Information or Illuminating New Physics? Universe 2017, 3, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe3030055

Chakraborty S, Lochan K. Black Holes: Eliminating Information or Illuminating New Physics? Universe. 2017; 3(3):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe3030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakraborty, Sumanta, and Kinjalk Lochan. 2017. "Black Holes: Eliminating Information or Illuminating New Physics?" Universe 3, no. 3: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe3030055

APA StyleChakraborty, S., & Lochan, K. (2017). Black Holes: Eliminating Information or Illuminating New Physics? Universe, 3(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe3030055