Abstract

Lectins are a class of proteins responsible for several biological roles such as cell-cell interactions, signaling pathways, and several innate immune responses against pathogens. Since lectins are able to bind to carbohydrates, they can be a viable target for targeted drug delivery systems. In fact, several lectins were approved by Food and Drug Administration for that purpose. Information about specific carbohydrate recognition by lectin receptors was gathered herein, plus the specific organs where those lectins can be found within the human body.

1. Introduction

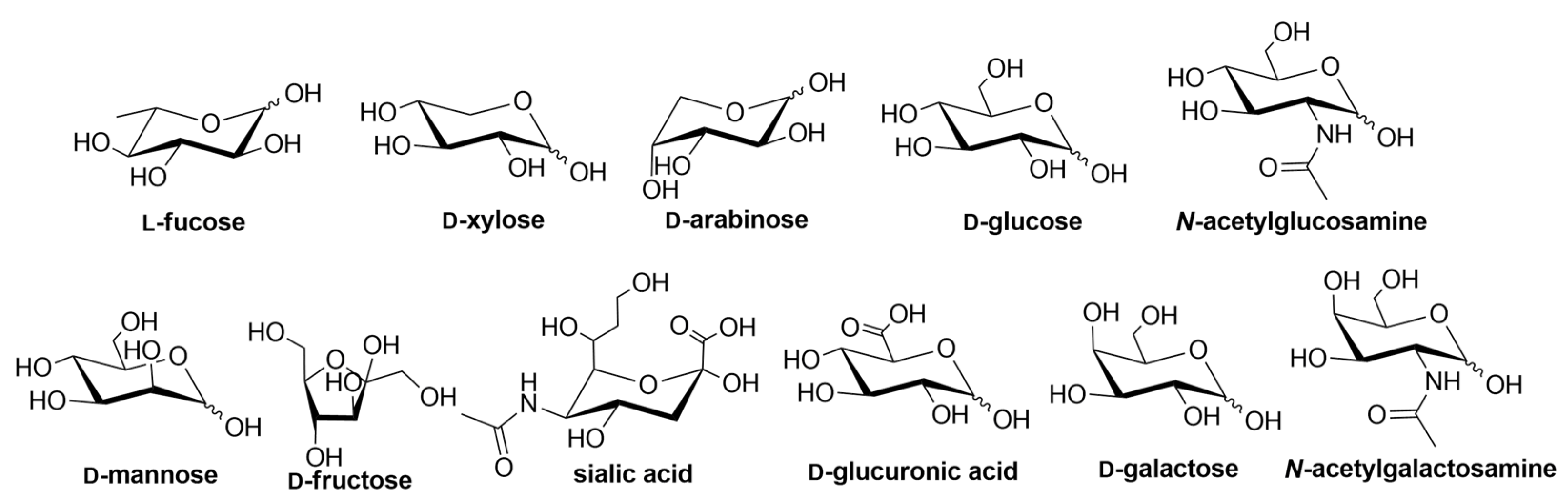

Lectins are an attractive class of proteins of non-immune origin that can either be free or linked to cell surfaces, and are involved in numerous biological processes, such as cell-cell interactions, signaling pathways, cell development, and immune responses [1]. Lectins selectively recognize carbohydrates and reversibly bind to them as long as the ligands are oriented in a specific manner. Some of the commonly occurring carbohydrates that are found in Nature are d-fructose, d-galactose, l-arabinose, d-xylose, d-mannose, d-glucose, d-glucosamine, d-galactosamine, l-fucose, various uronic acids, sialic acid, and their combinations to form other di- and oligosaccharides, or other biomolecules (Figure 1) [2].

Figure 1.

Structures of the carbohydrate building blocks found in Nature.

Lectins in vertebrates can be classified either by their subcellular location, or by their structure. Division based on their location includes integral lectins located in membranes as structural components, or soluble lectins present in intra- and intercellular fluids, which can move freely.

Division according to lectin structure consists of several different types of lectins, such as C-type lectins (binding is Ca2+ dependent), I-type lectins (carbohydrate recognition domain is similar to immunoglobulins), galectin family (or S-type, which are thiol dependent), pentraxins (pentameric lectins) and P-type lectins (specific to glycoproteins containing mannose 6-phosphate) [3].

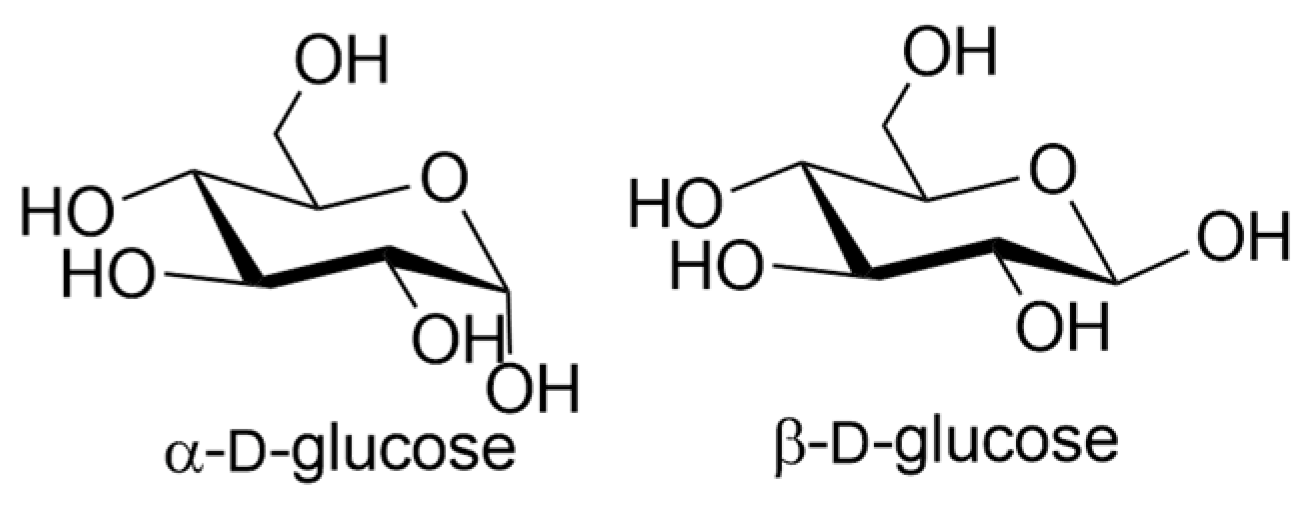

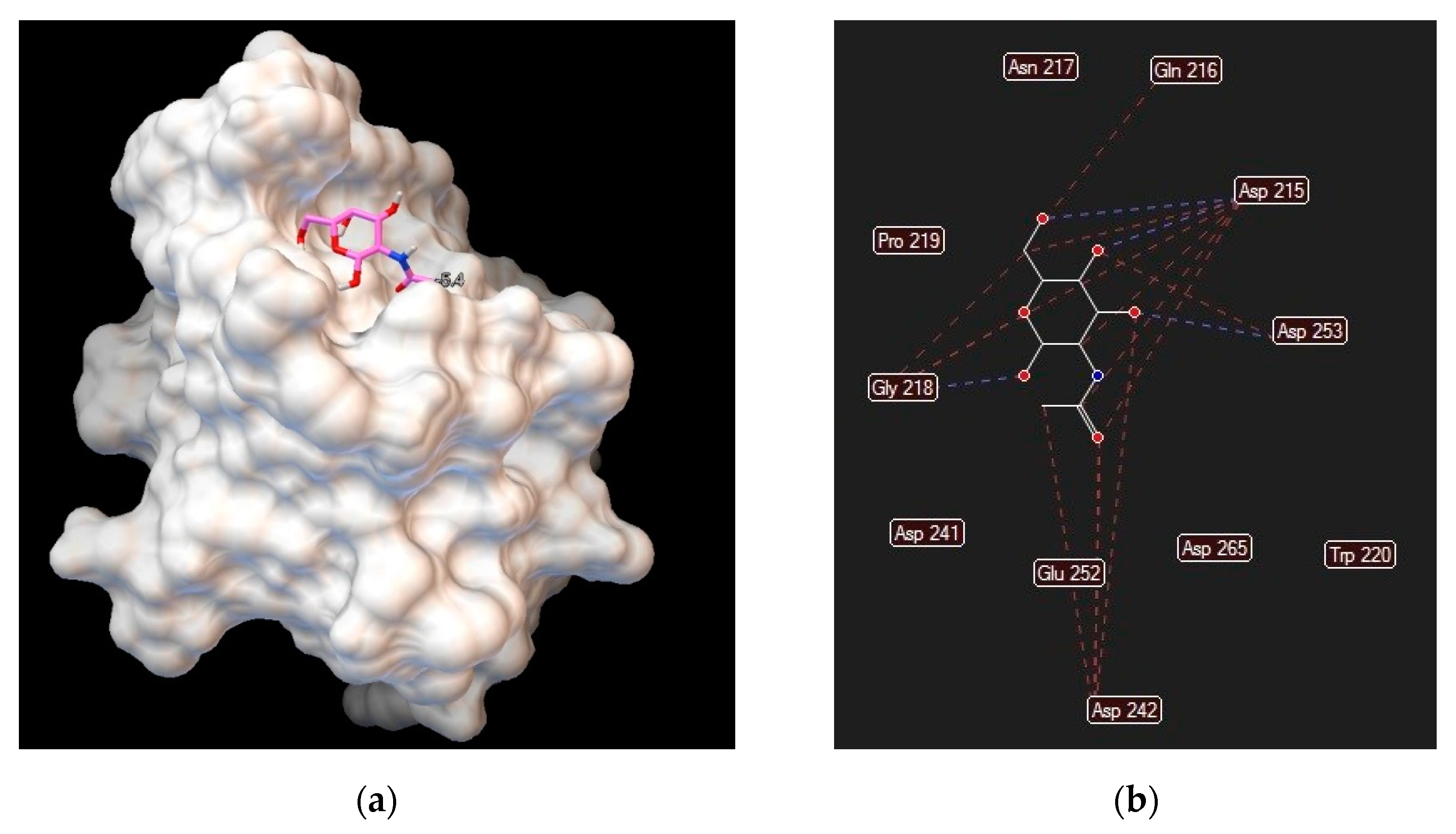

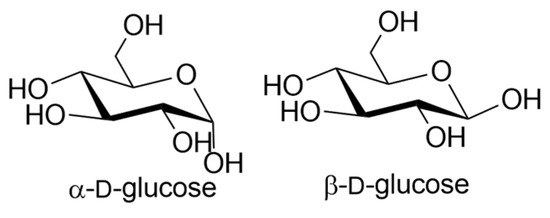

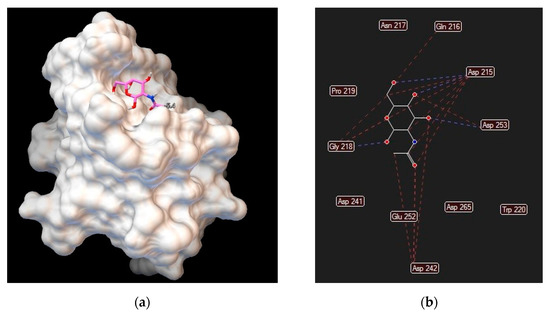

Different lectins have high similarity in the residues that bind to saccharides, most of which coordinate to metal ions, and water molecules. Nearly all animal lectins possess several pockets that recognize molecules other than carbohydrates, meaning that they are multivalent and can present 2 to 12 sites of interaction, allowing the binding of several ligands simultaneously. The specificity and affinity of the lectin-carbohydrate complex depends on the lectin, which can be very sensitive to the structure of the carbohydrate (e.g., mannose versus glucose, Figure 1), or to the orientation of the anomeric substituent (α versus β anomer, e.g., in Figure 2), or both. Lectin-carbohydrate interactions are achieved mainly through hydrogen bonds, van der Waals (steric interactions), and hydrophobic forces (example is given in Figure 3) [3,4].

Figure 2.

Structures of α- and β-d-glucose.

Figure 3.

Asialoglycoprotein receptor (Protein Data Bank entry 1DV8, gene symbol ASGR1) binding interactions with N–acetylgalactosamine: (a) ligand conformation inside the binding site; (b) specific interactions are hydrogen bonds (blue dashed lines) and steric interactions (red dashed lines).

It has been shown that the majority of lectins are conserved through evolution, suggesting that these proteins play a crucial role in the sugar-recognition activities necessary for the living process and development [5,6].

Although lectins are present in animals, plants, lichens, bacteria, and higher fungi [3], this review focuses only on human lectins for targeted drug delivery [7] purposes, their specificity towards carbohydrates and the organs where they are expressed. When referring to gene expression (or RNA expression), one means that those specific organs or cells have that specific gene coded. If active, it produces the respective protein, and one says that the protein is expressed in that organ or cell. In this review, we focus only on protein expression, since that information is the only relevant one for the development of targeted drug delivery systems. More information about carbohydrate-based nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery systems can be found elsewhere [8,9,10]. Since lectins are able to recognize and transport carbohydrates and their derivatives, lectin targeting can be relevant in the research and development of new medicines [7,11,12]. The metabolism of cancer cells, for example, is different from normal cells due to intense glycolytic activity (Warburg effect) [13]. Cancer cells require glutamine and/or glucose for cell growth, and glucose transporter isoforms 1 and 2 (gene symbols GLUT1 and GLUT2, respectively) showed an increase in activity in several tumors (gastrointestinal carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, breast carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, gastric and ovarian cancer) [14,15].

The herein adopted lectin nomenclature is in accordance with the Human Genome Group (HUGO) Gene Nomenclature Committee. However, most common designated aliases (non-standard names) are also included (and appear first). The expression data for all lectin-coding genes was compiled from The Human Protein Atlas [16,17] and GeneCards [18] databases.

2. C-Type Lectins

C-type lectins are involved in the recognition of saccharides in a Ca2+-dependent manner but exhibit low affinities to carbohydrates, requiring multiple valencies of carbohydrate ligands to mediate signaling pathways, such as DC-SIGN2 which gene symbol is CLEC4M (Most genes carry the information to make proteins. The gene name is often used when referring to the corresponding protein). MINCLE (gene symbol CLEC4E), on the other hand, shows high affinity and can detect small numbers of glycolipids on fungal surfaces [19,20]. Most of the lectin-like domains contain some of the conserved residues required to establish the domain fold, but do not present the residues required for carbohydrate recognition [21]. The amino acid residues known to be involved in calcium-dependent sugar-binding are the EPN motif (mannose-binding), the QPD motif (for galactose binding), and the WND motif (for Ca2+binding) [22]. More information about glycan affinity and binding to proteins can be found elsewhere [23]. A comprehensive list of C-type lectins is presented in Table 1, divided by subfamilies that differ in the architecture of the domain [22,24], along with the carbohydrates that they recognize and the human tissues where they are expressed.

Table 1.

C-type superfamily, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in human organs.

3. Chitolectins (or Chilectins)

There are two types of proteins that are able to recognize chitin: chitinases and chitolectins. The first ones are active proteins that bind and hydrolyze oligosaccharides, whereas the latter ones are able to bind oligosaccharides but do not hydrolyze them [76,77] and are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Human chitolectins (also called chilectins), their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

4. F-Type Lectins

F-type lectins, also called fucolectins, are characterized by an α-l-fucose recognition domain and display both unique carbohydrate- and calcium-binding sequence motifs [76]. F-type lectins are immune-recognition proteins and are presented in Table 3. Fucose is recognized by specific interactions with O5 (pyranose acetal oxygen), 3-OH and 4-OH [82], the reason why these atoms must be available to form these interactions after the synthesis of fucose derivatives.

Table 3.

Human f-type lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

5. F-Box Lectins

F-box proteins are the substrate-recognition subunits of the SCF (Skp1-Cul1-F-box protein) complex. They have an F-box domain that binds to S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 (Skp1) [84]. The F-box proteins were divided into three different classes: Fbws are those that contains WD-40 domains, Fbls containing leucine-rich repeats, and Fbxs that have either different protein-protein interaction modules or no recognizable motifs [85]. Although F-box proteins are a superfamily of proteins, only five are known to recognize N-linked glycoproteins [84] as presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Human F-box lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

6. Ficolins

Ficolins play an important role in innate immunity by recognizing and binding to carbohydrates present on the surface of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [89]. There are three human ficolins and they are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Human ficolins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

7. I-Type Lectins

I-type lectins are a subset of the immunoglobulin superfamily that specifically recognizes sialic acids and other carbohydrate ligands. Most of the members of this group of lectins are siglecs, which are type I transmembrane proteins, and can be divided into two groups: the CD33-related group that includes CD33 (siglec3) siglecs5–11, and siglec14 while the other group includes siglec1, CD22 (siglec2), MAG (siglec4) and Siglec15 [90,91]. CD33-related groups possess between 1 and 4 C-set domains and feature cytoplasmic tyrosine-based motifs involved in signaling and endocytosis. Siglec1 possesses 16 C-set domains, CD22 has 6 C-set domains and MAG presents 4 C-set domains. MAG is the only siglec not found on cells of the immune system. Members of this I-type superfamily are presented in Table 6 along with their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression. An example of a drug delivery system was developed by Spence, Greene and co-workers who developed polymeric nanoparticles of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) decorated with sialic acid [92,93].

Table 6.

Human I-type lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

8. L-Type Lectins

L-type lectins are distinguished from other lectins on the basis of tertiary structure, not the primary sequence, and are composed of antiparallel β-sheets connected by short loops and β-bends, usually lacking any α-helices [115]. Members of this family of lectins present different glycan-binding specificities as presented in Table 7. L-type superfamily includes Pentraxins [116,117] that require Ca2+ ions for ligand binding. Both LMAN1 and LMAN2 also require Ca2+ ions for their binding activity [115].

Table 7.

Human L-type lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

9. M-Type Lectins

M-type family of lectins consists of α-mannosidases, which are proteins involved in both the maturation and the degradation of Asn-linked oligosaccharides [127]. Members of this family, their binding affinities and protein expression are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Human M-type lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

10. P-Type Lectins

P-type lectins constitute a two-member family of mannose-6-phosphate receptors (Table 9) that play an essential role in the generation of functional lysosomes. The phosphate group is key to high-affinity ligand recognition by these proteins. Furthermore, optimal ligand-binding ability of M6PR is achieved in the presence of divalent cations, particularly Mn2+ cation [130,131].

Table 9.

Human P-type lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

11. R-Type Lectins

R-type lectins are protein-UDP acetylgalactosaminyltransferases that contain an R-type carbohydrate recognition domain, which is conserved between animal and bacterial lectins [135]. Members of this superfamily recognize Gal/GalNAc residues and are expressed in several tissues as presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Human R-type lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

12. S-Type Lectins

S-type lectins are known nowadays as galectins and are a superfamily of proteins that show a high affinity for β-galactoside sugars (Table 11). Formerly called S-type lectins because of their sulfhydryl dependency, galectins are the most widely expressed class of lectins in all organisms. Human galectins have been classified into three major groups according to their structure: prototypical, chimeric and tandem-repeat [151,152,153].

Galectins play important roles in immune responses and promoting inflammation. They are also known for having a crucial role in cancer-causing tumor invasion, progression, metastasis and angiogenesis [154,155,156].

Table 11.

Human S-type lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein epression in the organs.

Table 11.

Human S-type lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein epression in the organs.

|

Common Name (HUGO Name if Different) | Gene Symbol | Carbohydrate Preferential Affinity | Protein Expression in the Organs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Galectin 1 | |||

| Galectin 1 | LGALS1 | β-d-galactosides, poly-N-acetyllactosamine-enriched glycoconjugates [157,158] | Bone marrow, brain, cervix (uterine), endometrium, lymph node, ovary, parathyroid gland, placenta, smooth muscle, skin, spleen, testis, tonsil, vagina |

| Galectin 2 | LGALS2 | β-d-galactosides, lactose [159] | Appendix, colon, duodenum, gallbladder, kidney, liver, lymph node, pancreas, rectum, small intestine, spleen, tonsil |

| Galectin 3 | |||

| Galectin 3 | LGALS3 | β-d-galactosides, LacNAc [160] | Adipose and soft tissue, bone marrow and lymphoid tissues, brain, endocrine tissues, female tissues, gastrointestinal tract, kidney and urinary bladder, lung, male tissues, muscle tissues, pancreas, proximal digestive tract, skin |

| Galectin 3 binding protein | LGALS3BP | β-d-galactosides, lactose [161] | Adipose and soft tissue, bone marrow and lymphoid tissues, brain, female tissues, gastrointestinal tract, kidney and urinary bladder, lung, male tissues, muscle tissues, proximal digestive tract, skin |

| Galectin 4 | LGALS4 | β-d-galactosides, lactose [162] | Appendix, colon, duodenum, gallbladder, pancreas, rectum, small intestine, stomach |

| Galectin 7 | LGALS7 | Gal, GalNAc, Lac, LacNAc [163] | Cervix (uterine), esophagus, oral mucosa, salivary gland, skin, tonsil, vagina |

| Galectin 8 | LGALS8 | β-d-galactosides. Preferentially binds to 3′-O-sialylated and 3′-O-sulfated glycans [164] | Adipose and soft tissue, bone marrow and lymphoid tissues, brain, endocrine tissues, female tissues, gastrointestinal tract, kidney and urinary bladder, lung, male tissues, muscle tissues, pancreas, proximal digestive tract, skin |

| Galectin 9 | LGALS9 | β-d-galactosides. Forssman pentasaccharide, lactose, N-acetyllactosamine [165] | Adipose and soft tissue, bone marrow and lymphoid tissues, brain, endocrine tissues, female tissues, gastrointestinal tract, kidney and urinary bladder, lung, male tissues, muscle tissues, pancreas, proximal digestive tract, skin |

| Galectin 9B | LGALS9B | β-d-galactosides [166] | Appendix, bone marrow, breast, lymph node, spleen, tonsil |

| Galectin 9C | LGALS9C | β-d-galactosides [166] | Appendix, bronchus, colon, duodenum, gallbladder, lung, pancreas, spleen, stomach, tonsil |

| Galectin 10 (Charcot-Leyden crystal galectin, CLC) | LGALS10 | Binds weakly to lactose, N-acetyl-d-glucosamine and d-mannose [167] | Lymph node, spleen, tonsil |

| Galectin 12 | LGALS12 | β-d-galactose and lactose [168,169] | a) |

| Galectin 13 | LGALS13 | N-acetyl-lactosamine, mannose and N-acetyl-galactosamine [170]. Contrary to other galectins, Galectin 13 does not bind β-d-galactosides [171] | Kidney, placenta, spleen, urinary bladder |

| Placental Protein 13 (Galectin 14) | LGALS14 | N-acetyl-lactosamine [172] | Adrenal gland, colon, kidney |

| Galectin 16 | LGALS16 | N-acetyl-lactosamine, β-d-galactose and lactose [172] | Placenta |

a) Only RNA expression data available in The Human Protein Atlas [16,17] and GeneCards [18] databases.

13. X-Type Lectins

Intelectins (Table 12) were classified as X-type lectins because they do not have a typical lectin domain, instead, they contain a fibrinogen-like domain and a unique intelectin-specific region [173].

Table 12.

Human X-type lectins, their carbohydrate ligands and protein expression in the organs.

14. Orphans

Orphan lectins are those that do not belong to known lectin structural families [175]. Proteins that bind to sulfated glycosaminoglycans are usually not considered as lectins [101], however, the specific binding of these proteins to sulfated glycosaminoglycans can provide a valuable tool to develop targeted drug delivery systems. Glycosaminoglycan binding interactions with proteins were described in detail by Vallet, Clerc and Ricard-Blum [176] which information is outside of the scope of this review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D.R.; methodology, C.D.R. and A.B.C.; resources, M.T.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D.R.; writing—review and editing, A.B.C. and M.T.B.; visualization, C.D.R.; supervision, M.T.B.; funding acquisition, M.T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, grant number PD/BD/109680/2015. This work was also supported by the Associate Laboratory for Green Chemistry, LAQV, which is financed by national funds from FCT/MEC (UID/QUI/50006/2013 and UID/QUI/50006/2019) and co-financed by the ERDF under the PT2020 Partnership Agreement (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007265).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Christopher D. Maycock for having reviewed this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lepenies, B.; Lang, R. Lectins and Their Ligands in Shaping Immune Responses. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stick, R. Carbohydrates: The Sweet Molecules of Life, 1st ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.F.S.; Da Silva, M.D.C.; Napoleão, T.H.; Paiva, P.M.G.; Correia, M.T.S.; Coelho, L.C.B.B. Lectins: Function, structure, biological properties and potential applications. Curr. Top. Pept. Protein Res. 2014, 15, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Boons, G.-J. Carbohydrate Recognition: Biological Problems, Methods and Applications, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Danvers, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780470592076. [Google Scholar]

- Hirabayashi, J.; Kasai, K.I. Evolution of Animal Lectins. In Molecular Evolution: Evidence for Monophyly of Metazoa; Jeanteur, P., Kuchino, Y., Muller, W.E.G., Paine, P.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1998; Volume 19, ISBN 9783642487477. [Google Scholar]

- Drickamer, K. Evolution of Ca2+-dependent Animal Lectins. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1993, 45, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Himri, I.; Guaadaoui, A. Cell and organ drug targeting: Types of drug delivery systems and advanced targeting strategies. In Nanostructures for the Engineering of Cells, Tissues and Organs; Grumezescu, A., Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Norwich, UK, 2018; pp. 1–66. ISBN 9780128136652. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Jiang, X.; Hunziker, P. Carbohydrate-based amphiphilic nano delivery systems for cancer therapy. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 16091–16156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, G.; Huang, H. The glyconanoparticle as carrier for drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 1840–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaiab, T.; Farr, D.C.; Kiefel, M.J.; Houston, T.A. Carbohydrate-based nanocarriers and their application to target macrophages and deliver antimicrobial agents. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 151–152, 94–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, F.; Andreana, P.R. Developments in Carbohydrate-Based Cancer Therapeutics. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz-fathi, M.; Rezaei, N. Vaccines, Adjuvants, and Delivery Systems. In Vaccines for Cancer Immunotherapy; Keshavarz-Fathi, M., Rezaei, N., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 45–59. ISBN 9780128140390. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaradonna, F.; Moresco, R.M.; Airoldi, C.; Gaglio, D.; Palorini, R.; Nicotra, F.; Messa, C.; Alberghina, L. From cancer metabolism to new biomarkers and drug targets. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 30–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wesener, D.A.; Wangkanont, K.; McBride, R.; Song, X.; Kraft, M.B.; Hodges, H.L.; Zarling, L.C.; Splain, R.A.; Smith, D.F.; Cummings, R.D.; et al. Recognition of Microbial Glycans by Human Intelectin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knut & Alice Wallenberg Foundation. The Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GeneCards, version: 3.12.404; Weizmann Institute of Science: Rehovot, Israel, 2015.

- Furukawa, A.; Kamishikiryo, J.; Mori, D.; Toyonaga, K.; Okabe, Y.; Toji, A.; Kanda, R.; Miyake, Y.; Ose, T.; Yamasaki, S.; et al. Structural analysis for glycolipid recognition by the C-type lectins Mincle and MCL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17438–17443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, H.; Park-snyder, S.; Kolatkar, A.R.; Heise, C.T.; Taylor, M.E.; Weis, W.I. Structure of a C-type Carbohydrate Recognition Domain from the Macrophage Mannose Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 21539–21548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, E.J.; Marshall, A.J.; Magaletti, D.; Floyd, H.; Draves, K.E.; Olson, N.E.; Clark, E.A. Dendritic Cell-Associated Lectin-1: A Novel Dendritic Cell-Associated, C-Type Lectin-Like Molecule Enhances T Cell Secretion of IL-4. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 5638–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, R.D.; McEver, R.P. C-Type Lectins. In Essentials of Glycobiology; Varki, A., Cummings, R.D., Esko, J.D., Freeze, H.H., Stanley, P., Bertozzi, C.R., Gerald, H.W., Etzler, M.E., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, R.D.; Esko, J.D. Principles of Glycan Recognition. In Essentials of Glycobiology; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial College Human CTLD Database. Available online: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/research/animallectins/ctld/mammals/humandataupdated.html (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Olin, A.I.; Mörgelin, M.; Sasaki, T.; Timpl, R.; Heinegård, D.; Aspberg, A. The proteoglycans aggrecan and versican form networks with fibulin-2 through their lectin domain binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, D.M.; Kelly, G.M.; Hockfield, S. BEHAB, a New Member of the Proteoglycan Tandem Repeat Family of Hyaluronan-binding Proteins That Is Restricted to the Brain. J. Cell Biol. 1994, 125, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y. Brevican: A major proteoglycan in adult brain. Perspect. Dev. Neurobiol. 1996, 3, 307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, U.; Gao, P.; Janetzko, A.; Flaccus, A.; Hilgenberg, L.; Tekotte, H.; Margolis, R.K.; Margolis, R.U. Isolation and characterization of developmentally regulated chondroitin sulfate and chondroitin/keratin sulfate proteoglycans of brain identified with monoclonal antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 14785–14801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, R.G.; Zimmermann, D.R.; Ruoslahti, E. Hyaluronate binding properties of versican. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 10003–10010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riboldi, E.; Daniele, R.; Parola, C.; Inforzato, A.; Arnold, P.L.; Bosisio, D.; Fremont, D.H.; Bastone, A.; Colonna, M.; Sozzani, S. Human C-type lectin domain family 4, member C (CLEC4C/BDCA-2/CD303) is a receptor for asialo-galactosyl-oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 35329–35333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jégouzo, S.A.F.; Feinberg, H.; Dungarwalla, T.; Drickamer, K.; Weis, W.I.; Taylor, M.E. A novel mechanism for binding of galactose-terminated glycans by the C-type carbohydrate recognition domain in blood dendritic cell antigen 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 16759–16771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurtsen, J.; Driessen, N.N.; Appelmelk, B.J. Mannose–fucose recognition by DC-SIGN. In Microbial Glycobiology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 673–695. ISBN 978-0-12-374546-0. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, H.; Jégouzo, S.A.F.; Rex, M.J.; Drickamer, K.; Weis, W.I.; Taylor, M.E. Mechanism of pathogen recognition by human dectin-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13402–13414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, A.K.; Vyas, J.M. Host Defenses to Fungal Pathogens. In Clinical Immunology; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 413–424.e1. ISBN 9780702068966. [Google Scholar]

- Nagae, M.; Ikeda, A.; Hanashima, S.; Kojima, T.; Matsumoto, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Yamaguchi, Y. Crystal structure of human dendritic cell inhibitory receptor C-type lectin domain reveals the binding mode with N-glycan. FEBS Lett. 2016, 590, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.D. Human CD23: Is It a Lectin in Disguise? Structure 2006, 14, 950–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kijimoto-Ochiai, S.; Toshimitsu, U. CD23 molecule acts as a galactose-binding lectin in the cell aggregation of EBV-transformed human B-cell lines. Glycobiology 1995, 5, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.; Bider, M.D.; Malashkevich, V.N.; Spiess, M.; Burkhard, P. Crystal structure of the carbohydrate recognition domain of the H1 subunit of the asialoglycoprotein receptor. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 300, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Chen, J.B.; Tsai, T.F.; Tsai, Y.C.; Tsai, C.Y.; Liang, P.H.; Hsu, T.L.; Wu, C.Y.; Netea, M.G.; Wong, C.H.; et al. CLEC4F Is an Inducible C-Type Lectin in F4/80-Positive Cells and Is Involved in Alpha-Galactosylceramide Presentation in Liver. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambach, N.S.; Taylor, M.E. Characterization of carbohydrate recognition by langerin, a C-type lectin of Langerhans cell. Glycobiology 2003, 13, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tang, L.; Zhang, G.; Wei, H.; Cui, Y.; Guo, L.; Gou, Z.; Chen, X.; Jiang, D.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Characterization of a novel C-type lectin-like gene, LSECtin: Demonstration of carbohydrate binding and expression in sinusoidal endothelial cells of liver and lymph node. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 18748–18758. [Google Scholar]

- Nollau, P.; Wolters-Eisfeld, G.; Mortezai, N.; Kurze, A.K.; Klampe, B.; Debus, A.; Bockhorn, M.; Niendorf, A.; Wagener, C. Protein Domain Histochemistry (PDH): Binding of the Carbohydrate Recognition Domain (CRD) of Recombinant Human Glycoreceptor CLEC10A (CD301) to Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Breast Cancer Tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2013, 61, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.B.; Williams, S.J. MCL and Mincle: C-type lectin receptors that sense damaged self and pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatraman Girija, U.; Furze, C.M.; Gingras, A.R.; Yoshizaki, T.; Ohtani, K.; Marshall, J.E.; Wallis, A.K.; Schwaeble, W.J.; El-Mezgueldi, M.; Mitchell, D.A.; et al. Molecular basis of sugar recognition by collectin-K1 and the effects of mutations associated with 3MC syndrome. BMC Biol. 2015, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtani, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Eda, S.; Kawai, T.; Kase, T.; Yamazaki, H.; Shimada, T.; Keshi, H.; Sakai, Y.; Fukuoh, A.; et al. Molecular cloning of a novel human collectin from liver (CL-L1). J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 13681–13689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muto, S.; Sakuma, K.; Taniguchi, A.; Matsumoto, K. Human mannose-binding lectin preferentially binds to human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines expressing high amount of Lewis A and Lewis B antigens. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 22, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wright, J.R. Immunoregulatory functions of surfactant proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, P.J.; Graham, S.A.; Drickamert, K.; Taylor, M.E. Selective binding of the scavenger receptor C-type lectin to Lewis x trisaccharide and related glycan ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 22993–22999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, D.V.; Watson, S.R.; Presta, L.G.; Wolitzky, B.A.; Foxall, C.; Brandley, B.K.; Lasky, L.A. P- and E-selectin use common sites for carbohydrate ligand recognition and cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 120, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivetic, A.; Green, H.L.H.; Hart, S.J. L-selectin: A major regulator of leukocyte adhesion, migration and signaling. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P.S.; Hsieh, S.L. CLEC2 and CLEC5A: Pathogenic Host Factors in Acute Viral Infections. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsack, R.; Pecht, I. The mast cell function-associated antigen exhibits saccharide binding capacity. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997, 27, 2557–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Arsequell, G. Immunobiology of Carbohydrates; Wong, S., Arsequell, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roda-Navarro, P.; Arce, I.; Renedo, M.; Montgomery, K.; Kucherlapati, R.; Fernández-Ruiz, E. Human KLRF1, a novel member of the killer cell lectin-like receptor gene family: Molecular characterization, genomic structure, physical mapping to the NK gene complex and expression analysis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000, 30, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohki, I.; Ishigaki, T.; Oyama, T.; Matsunaga, S.; Xie, Q.; Ohnishi-Kameyama, M.; Murata, T.; Tsuchiya, D.; Machida, S.; Morikawa, K.; et al. Crystal structure of human lectin-like, oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 ligand binding domain and its ligand recognition mode to OxLDL. Structure 2005, 13, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higai, K.; Imaizumi, Y.; Suzuki, C.; Azuma, Y.; Matsumoto, K. NKG2D and CD94 bind to heparin and sulfate-containing polysaccharides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 386, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiffoleau, E. C-type lectin-like receptors as emerging orchestrators of sterile inflammation represent potential therapeutic targets. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.A.; Brown, J.; Harlos, K.; Eble, J.A.; Walter, T.S.; O’Callaghan, C.A. The crystal structure and mutational binding analysis of the extracellular domain of the platelet-activating receptor CLEC-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 3165–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.G.; Czabotar, P.E.; Policheni, A.N.; Caminschi, I.; San Wan, S.; Kitsoulis, S.; Tullett, K.M.; Robin, A.Y.; Brammananth, R.; van Delft, M.F.; et al. The Dendritic Cell Receptor Clec9A Binds Damaged Cells via Exposed Actin Filaments. Immunity 2012, 36, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorey, J.; Lawrence, C. The Pattern Recognition Receptor Dectin-1: From Fungi to Mycobacteria. Curr. Drug Targets 2008, 9, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gange, C.T.; Quinn, J.M.W.; Zhou, H.; Kartsogiannis, V.; Gillespie, M.T.; Ng, K.W. Characterization of sugar binding by osteoclast inhibitory lectin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 29043–29049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, D.; Mouhtouris, E.; Milland, J.; Zingoni, A.; Santoni, A.; Sandrin, M.S. Recognition of a carbohydrate xenoepitope by human NKRP1A (CD161). Xenotransplantation 2006, 13, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogelberg, H.; Frenkiel, T.A.; Birdsall, B.; Chai, W.; Muskett, F.W. Binding of Sucrose Octasulphate to the C-Type Lectin-Like Domain of the Recombinant Natural Killer Cell Receptor NKR-P1A Observed by NMR Spectroscopy. ChemBioChem 2002, 3, 1072–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaizumi, Y.; Higai, K.; Suzuki, C.; Azuma, Y.; Matsumoto, K. NKG2D and CD94 bind to multimeric α2,3-linked N-acetylneuraminic acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 382, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- East, L.; Rushton, S.; Taylor, M.E.; Isacke, C.M. Characterization of sugar binding by the mannose receptor family member, Endo180. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 50469–50475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.E.; Bezouska, K.; Drickamer, K. Contribution to ligand binding by multiple carbohydrate-recognition domains in the macrophage mannose receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Downing, S.; Tzanakakis, E.S. Four Decades After the Discovery of Regenerating Islet-Derived (Reg) Proteins: Current Understanding and Challenges. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, L.; Smits, P.; Wauters, J.; Merregaert, J. Molecular cloning and characterization of human chondrolectin, a novel type I transmembrane protein homologous to C-type lectins. Genomics 2002, 80, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, P.; Rubin, K.; Higgins, J.M.G.; Hynes, R.O. Layilin, a novel integral membrane protein, is a hyaluronan receptor. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neame, P.J.; Tapp, H.; Grimm, D.R. The cartilage-derived, C-type lectin (CLECSF1): Structure of the gene and chromosomal location. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Struct. Expr. 1999, 1446, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletnev, V.; Huether, R.; Habegger, L.; Habegger, L.; Schultz, W.; Duax, W. Rational proteomics of PKD1. I. Modeling the three dimensional structure and ligand specificity of the C_lectin binding domain of Polycystin-1. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, T.-H.; Silveira, P.A.; Fromm, P.D.; Verma, N.D.; Vu, P.A.; Kupresanin, F.; Adam, R.; Kato, M.; Cogger, V.C.; Clark, G.J.; et al. Characterization of the Expression and Function of the C-Type Lectin Receptor CD302 in Mice and Humans Reveals a Role in Dendritic Cell Migration. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, G.J.; Myszka, D.G.; Katsamba, P.S.; Ohnuki, L.E.; Gleich, G.J.; Acharya, K.R. Eosinophil-granule major basic protein, a C-type lectin, binds heparin. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 14152–14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L.; Pai, F.S.; Tsou, Y.T.; Mon, H.C.; Hsu, T.L.; Wu, C.Y.; Chou, T.Y.; Yang, W.B.; Chen, C.H.; Wong, C.H.; et al. Human CLEC18 gene cluster contains C-type lectins with differential glycan-binding specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 21252–21263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, S.A.; Jégouzo, S.A.F.; Yan, S.; Powlesland, A.S.; Brady, J.P.; Taylor, M.E.; Drickamer, K. Prolectin, a glycan-binding receptor on dividing b cells in germinal centers. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 18537–18544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, P.; Aronson, N.N., Jr.; Madura, J.D. Family 18 Chitolectins: Comparison of MGP40 and HUMGP39. Bichem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2007, 359, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, D.C. Animal lectins: A historical introduction and overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1572, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkema, G.H.; Boot, R.G.; Au, F.L.; Donker-Koopman, W.E.; Strijland, A.; Muijsers, A.O.; Hrebicek, M.; Aerts, J.M.F.G. Chitotriosidase a chitinase, and the 39-kDa human cartilage glycoprotein, a chitin-binding lectin, are homologues of family 18 glycosyl hydrolases secreted by human macrophages. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 251, 504–509. [Google Scholar]

- Boot, R.G.; Blommaart, E.F.C.; Swart, E.; Ghauharali-van der Vlugt, K.; Bijl, N.; Moe, C.; Place, A.; Aerts, J.M.F.G. Identification of a Novel Acidic Mammalian Chitinase Distinct from Chitotriosidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 6770–6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusetti, F.; Pijning, T.; Kalk, K.H.; Bos, E.; Dijkstra, B.W. Crystal structure and carbohydrate-binding properties of the human cartilage glycoprotein-39. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 37753–37760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimpl, M.; Rush, C.L.; Betou, M.; Eggleston, I.M.; Recklies, A.D.; Van Aalten, D.M.F. Human YKL-39 is a pseudo-chitinase with retained chitooligosaccharide-binding properties. Biochem. J. 2012, 446, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malette, B.; Paquette, Y.; Merlen, Y.; Bleau, G. Oviductins possess chitinase- and mucin-like domains: A lead in the search for the biological function of these oviduct-specific ZP-associating glycoproteins. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1995, 41, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, N.N.; Kuranda, M.J. Lysosomal degradation of Asn-linked glycoproteins. FASEB J. 1989, 3, 2615–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, X.; Liu, Y.; Green, T.J.; Luo, M.; Zheng, X. Structure of human Stabilin-1 Interacting Chitinase-Like Protein (SI-CLP) reveals a saccharide-binding cleft with lower sugar-binding selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 39898–39904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchet, M.A.; Odom, E.W.; Vasta, G.R.; Amzel, L.M. A novel fucose recognition fold involved in innate immunity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002, 9, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasta, G.R.; Mario Amzel, L.; Bianchet, M.A.; Cammarata, M.; Feng, C.; Saito, K. F-Type Lectins: A highly diversified family of fucose-binding proteins with a unique sequence motif and structural fold, involved in self/non-self-recognition. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, Y. F-box proteins that contain sugar-binding domains. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cenciarelli, C.; Chiaur, D.S.; Guardavaccaro, D.; Parks, W.; Vidal, M.; Pagano, M. Identification of a family of human F-box proteins. Curr. Biol. 1999, 9, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, T.; Hirao, T.; Yoshida, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Chiba, T.; Iwai, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kato, K.; Tsukihara, T.; Tanaka, K. Structural basis of sugar-recognizing ubiquitin ligase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004, 11, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y. A novel role for N-glycans in the ERAD system. J. Biochem. 2003, 134, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, K.A.; Nelson, R.F.; Wen, H.M.; Mallinger, A.J.; Paulson, H.L. Diversity in tissue expression, substrate binding, and SCF complex formation for a lectin family of ubiquitin ligases. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 12717–12729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M. Ficolins: Complement-activating lectins involved in innate immunity. J. Innate Immun. 2009, 2, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Yang, G. A comparative review of intelectins. Scand. J. Immunol. 2020, 92, e12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, P.R.; Redelinghuys, P. Siglecs as positive and negative regulators of the immune system. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008, 36, 1467–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varki, A.; Angata, T. Siglecs—The major subfamily of I-type lectins. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, S.; Greene, M.K.; Fay, F.; Hams, E.; Saunders, S.P.; Hamid, U.; Fitzgerald, M.; Beck, J.; Bains, B.K.; Smyth, P.; et al. Targeting Siglecs with a sialic acid-decorated nanoparticle abrogates inflammation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, P.R.; Kelm, S.; Dubois, C.; Martin, B.; McWilliam, A.S.; Shotton, D.M.; Paulson, J.C.; Gordon, S. Purification and properties of sialoadhesin, a sialic acid-binding receptor of murine tissue macrophages. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.D.; Varki, A. The oligosaccharide binding specificities of CD22β, a sialic acid- specific lectin of B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 10628–10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelm, S.; Pelz, A.; Schauer, R.; Filbin, M.T.; Tang, S.; de Bellard, M.E.; Schnaar, R.L.; Mahoney, J.A.; Hartnell, A.; Bradfield, P.; et al. Sialoadhesin, myelin-associated glycoprotein and CD22 define a new family of sialic acid-dependent adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Curr. Biol. 1994, 4, 965–972. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, S.D.; Kelm, S.; Barber, E.K.; Crocker, P.R. Characterization of CD33 as a new member of the sialoadhesin family of cellular interaction molecules. Blood 1995, 85, 2005–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.E.; Yang, L.J.S.; Mukhopadhyay, G.; Filbin, M.T.; Kiso, M.; Hasegawa, A.; Schnaar, R.L. Sialic acid specificity of myelin-associated glycoprotein binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, A.L.; Freeman, S.; Forbes, G.; Ni, J.; Zhang, M.; Cepeda, M.; Gentz, R.; Augustus, M.; Carter, K.C.; Crocker, P.R. Characterization of siglec-5, a novel glycoprotein expressed on myeloid cells related to CD33. Blood 1998, 92, 2123–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Der Linden, E.C.M.B.; Altmann, S.W.; Gish, K.; Balasubramanian, S.; Timans, J.C.; Peterson, D.; Bell, M.P.; Bazan, J.F.; Varki, A.; et al. OB-BP1/Siglec-6 A Leptin and Sialic Acid-Binding Protein of The Immunoglobulin Superfamily. J. Biol. 1999, 274, 22729–22738. [Google Scholar]

- Angata T, Brinkman-Van der Linden E. I-type lectins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1572, 294–316. [CrossRef]

- Nicoll, G.; Ni, J.; Liu, D.; Klenermani, P.; Munday, J.; Dubock, S.; Mattei, M.G.; Crocker, P.R.; Floyd, H.; Ni, J.; et al. Identification and characterization of a novel Siglec, Siglec-7, expressed by human natural killer cells and monocytes. Siglec-8: A novel eosinophil-specific member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Chemtracts 2000, 13, 689–694. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, A.; Handa, K.; Withers, D.A.; Satoh, M.; Hakomori, S. itiroh Binding specificity of siglec7 to disialogangliosides of renal cell carcinoma: Possible role of disialogangliosides in tumor progression. FEBS Lett. 2001, 504, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, M.; Biassoni, R.; Bottino, C.; Vitale, M.; Sivori, S.; Augugliaro, R.; Moretta, L.; Moretta, A. Identification and molecular cloning of p75/AIRM1, a novel member of the sialoadhesin family that functions as an inhibitory receptor in human natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 190, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, H.; Ni, J.; Cornish, A.L.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, D.; Carter, K.C.; Steel, J.; Crocker, P.R. Siglec-8 A novel Eosinophil-Specific member of The Immunoglobulin Superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Nicoll, G.; Jones, C.; Crocker, P.R. Siglec-9, a novel sialic acid binding member of the immunoglobulin superfamily expressed broadly on human blood leukocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 22121–22126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, J.; Kerr, S.; Ni, J.; Cornish, A.L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Nicoll, G.; Floyd, H.; Mattei, M.G.; Moore, P.; Liu, D.; et al. Identification, characterization and leucocyte expression of Siglec-10, a novel human sialic acid-binding receptor. Biochem. J. 2001, 355, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angata, T.; Hayakawa, T.; Yamanaka, M.; Varki, A.; Nakamura, M. Discovery of Siglec-14, a novel sialic acid receptor undergoing concerted evolution with Siglec-5 in primates. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1964–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angata, T.; Tabuchi, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Nakamura, M. Siglec-15: An immune system Siglec conserved throughout vertebrate evolution. Glycobiology 2007, 17, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, H.S.; Altin, J.G.; Waldron, J.C.; Kinnear, B.F.; Parish, C.R. A carbohydrate structure associated with CD15 (Lewisx) on myeloid cells is a novel ligand for human CD2. J. Immunol. 1996, 156, 2866–2873. [Google Scholar]

- Scholler, N.; Hayden-Ledbetter, M.; Hellström, K.-E.; Hellström, I.; Ledbetter, J.A. CD83 Is a Sialic Acid-Binding Ig-Like Lectin (Siglec) Adhesion Receptor that Binds Monocytes and a Subset of Activated CD8 + T Cells. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 3865–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCourt, P.A.G.; Ek, B.; Forsberg, N.; Gustafson, S. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 is a cell surface receptor for hyaluronan. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 30081–30084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleene, R.; Yang, H.; Kutsche, M.; Schachner, M. The Neural Recognition Molecule L1 is a Sialic Acid-binding Lectin for CD24, Which Induces Promotion and Inhibition of Neurite Outgrowth. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 21656–21663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horstkorte, R.; Schachner, M.; Magyar, J.P.; Vorherr, T.; Schmitz, B. The fourth immunoglobulin-like domain of NCAM contains a carbohydrate recognition domain for oligomannosidic glycans implicated in association with L1 and neurite outgrowth. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 121, 1409–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzler, M.E.; Surolia, A.; Cummings, R.D. L-Type Lectins. In Essentials of Glycobiology; Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bottazzi, B.; Garlanda, C.; Teixeira, M.M. The Role of Pentraxins: From Inflammation, Tissue Repair and Immunity to Biomarkers; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 9782889633876. [Google Scholar]

- Clos, T.W. Du Pentraxins: Structure, Function, and Role in Inflammation. ISRN Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, F.E.; Vassilakos, A.; Peterson, P.A.; Jackson, M.R.; Lehrman, M.A.; Williams, D.B. The molecular chaperone calnexin binds Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide as an initial step in recognizing unfolded glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 4697–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiro, R.G.; Zhu, Q.; Bhoyroo, V.; Söling, H.D. Definition of the lectin-like properties of the molecular chaperone, calreticulin, and demonstration of its copurification with endomannosidase from rat liver Golgi. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 11588–11594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Page, R.C.; Das, V.; Nix, J.C.; Wigren, E.; Misra, S.; Zhang, B. Structural characterization of carbohydrate binding by LMAN1 protein provides new insight into the endoplasmic reticulum export of factors V (FV) and VIII (FVIII). J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 20499–20509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Arata, Y.; Kasai, K.I.; Ihara, Y.; Matsuo, I.; Ito, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Kato, K. Sugar-binding properties of VIP36, an intracellular animal lectin operating as a cargo receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 37178–37182. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya, Y.; Kamiya, D.; Yamamoto, K.; Nyfeler, B.; Hauri, H.P.; Kato, K. Molecular basis of sugar recognition by the human L-type lectins ERGIC-53, VIPL, and VIP36. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 1857–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, K. Characterization of the binding of serum amyloid P to Laminin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 2143–2148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Köttgen, E.; Hell, B.; Kage, A.; Tauber, R.; Kottgen, E. Lectin specificity and binding characteristics of human C-reactive protein. J. Immunol. 1992, 149, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.T.; Lee, Y.C. Carbohydrate ligands of human C-reactive protein: Binding of neoglycoproteins containing galactose-6-phosphate and galactose-terminated disaccharide. Glycoconj. J. 2006, 23, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deban, L.; Jarva, H.; Lehtinen, M.J.; Bottazzi, B.; Bastone, A.; Doni, A.; Jokiranta, T.S.; Mantovani, A.; Meri, S. Binding of the Long Pentraxin PTX3 to Factor H: Interacting Domains and Function in the Regulation of Complement Activation. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 8433–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, D.S.; Jordan, I.K. The alpha-Mannosidases: Phylogeny and Adaptive Diversification. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vallet, S.D.; Clerc, O.; Ricard-Blum, S. Glycosaminoglycan–Protein Interactions: The First Draft of the Glycosaminoglycan Interactome. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2020, 0022155420946403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, J.; Kornfeld, R. The soluble form of rat liver α-mannosidase is immunologically related to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane α-mannosidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 4758–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, L.O.; Dyke, N.C.; Herscovics, A. Molecular cloning, chromosomal mapping and tissue-specific expression of a novel human α1,2-mannosidase gene involved in N-glycan maturation. Glycobiology 1998, 8, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahms, N.M.; Hancock, M.K. P-type lectins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2002, 1572, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P.Y.; Gregory, W.; Kornfeld, S. Ligand interactions of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. The stoichiometry of mannose 6-phosphate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 7962–7969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P.Y.; Kornfeld, S. Ligand interactions of the cation-dependent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Comparison with the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 7970–7975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary-Bobo, M.; Nirde, P.; Jeanjean, A.; Morere, A.; Garcia, M. Mannose 6-Phosphate Receptor Targeting and its Applications in Human Diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 2945–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, R.D.; Schnaar, R.L. R-Type Lectins. In Essentials of Glycobiology; Varki, A., Cummings, R.D., Esko, J.D., Stanley, P., Hart, G.W., Aebi, M., Darvill, A.G., Kinoshita, T., Packer, N.H., Prestegard, J.H., et al., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, H.; Bennett, E.P. A family of UDP-GalNAc: Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferases control the initiation of mucin-type O-linked glycosylation. Glycobiology 1996, 6, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tachibana, K.; Gotoh, M.; Kikuchi, N.; Kwon, Y.D.; Togayachi, A.; Kudo, T.; Kubota, T.; Narimatsu, H. Initiation of O-glycan synthesis in IgA1 hinge region is determined by a single enzyme, UDP-N-acetyl-α-D-galactosamine: Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 5613–5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, H.; Reis, C.A.; Bennett, E.P.; Mirgorodskaya, E.; Roepstorff, P.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Burchell, J.; Taylor-Papadimitriou, J.; Clausen, H. The lectin domain of UDP-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine: Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-T4 directs its glycopeptide specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 38197–38205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, E.P.; Hassan, H.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Clausen, H. A novel human UDP-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase, GalNAc-T7, with specificity for partial GalNAc-glycosylated acceptor substrates. FEBS Lett. 1999, 460, 226–230. [Google Scholar]

- White, K.E.; Lorenz, B.; Evans, W.E.; Meitinger, T.; Strom, T.M.; Econs, M.J. Molecular cloning of a novel human UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase, GalNAc-T8, and analysis as a candidate autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) gene. Gene 2000, 246, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toba, S.; Tenno, M.; Konishi, M.; Mikami, T.; Itoh, N.; Kurosaka, A. Brain-specific expression of a novel human UDP-GalNAc: Polypeptide N- acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (GalNAc-T9). Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Struct. Expr. 2000, 1493, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Tachibana, K.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.M.; Kahori Tachibana, K.; Kameyama, A.; Wang, H.; Hiruma, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Togayachi, A.; et al. Characterization of a novel human UDP-GalNAc transferase, pp-GalNAc-T10. FEBS Lett. 2002, 531, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskovski, M.T.; Yuan, S.; Pedersen, N.B.; Goth, C.K.; Makova, S.; Clausen, H.; Brueckner, M.; Khokha, M.K. The Heteroataxy gene, GALNT11, glycosylates Notch to orchestrate cilia type and laterality. Nature 2013, 504, 456–459. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Iwasaki, H.; Wang, H.; Kubota, T.; Tachibana, K.; Narimatsu, H. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel member of the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase family, pp-GalNAc-T12. FEBS Lett. 2002, 524, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Iwasaki, H.; Wang, H.; Kudo, T.; Kalka, T.B.; Hennet, T.; Kubota, T.; Cheng, L.; Inaba, N.; Gotoh, M.; et al. Cloning and characterization of a new human UDP-N-acetyl-α-D-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase, designated pp-GalNAc-T13, that is specifically expressed in neurons and synthesizes GalNAc α-serine/threonine antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Tachibana, K.; Zhang, Y.; Iwasaki, H.; Kameyama, A.; Cheng, L.; Guo, J.M.; Hiruma, T.; Togayachi, A.; Kudo, T.; et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase, pp-GalNAc-T14. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 300, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Tachibana, K.; Iwasaki, H.; Kameyama, A.; Zhang, Y.; Kubota, T.; Hiruma, T.; Tachibana, K.; Kudo, T.; Guo, J.M.; et al. Characterization of a novel human UDP-GalNAc transferase, pp-GalNAc-T15. FEBS Lett. 2004, 566, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, J.; Guan, Y.; Perrine, C.L.; Gerken, T.A.; Tabak, L.A. UDP-N-acetyl α-d-galactosamine: Polypeptide N- acetylgalactosaminyltransferases: Completion of the family tree. Glycobiology 2012, 22, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Oki, S.; Wakabayashi, M.; Ishihama, Y.; Miyake, A.; Itoh, N.; Kurosaka, A. A putative polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase/Williams-Beuren syndrome chromosome region 17 (WBSCR17) regulates lamellipodium formation and macropinocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 32222–32235. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Shao, D.; Xie, Y.; Xie, W.; Kubota, T.; Narimatsu, H.; Zhang, Y. Characterization of ppGalNAc-T18, a member of the vertebrate-specific y subfamily of UDP-N-acetyl-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N- acetylgalactosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology 2012, 22, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasaki, N.; Tachibana, K.; Ogasawara, S.; Matsuzaki, H.; Hagiuda, J.; Ishikawa, H.; Mochida, K.; Inoue, K.; Ogonuki, N.; Ogura, A.; et al. A heterozygous mutation of GALNTL5 affects male infertility with impairment of sperm motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, R.D.; Liu, F.-T. Galectins. In Essentials of Glycobiology; Varki, A., Cummings, R.D., Esko, J.D., Freeze, H.H., Stanley, P., Bertozzi, C.R., Gerald, H.W., Etzler, M.E., Eds.; Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johannes, L.; Jacob, R.; Leffler, H. Galectins at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barondes, S.H.; Cooper, D.N.W.; Gitt, M.A.; Leffler, H. Galectins. Structure and function of a large family of animal lectins. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 20807–20810. [Google Scholar]

- Chetry, M.; Thapa, S.; Hu, X.; Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, X. The role of galectins in tumor progression, treatment and prognosis of gynecological cancers. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 4742–4755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ebrahim, A.H.; Alalawi, Z.; Mirandola, L.; Rakhshanda, R.; Dahlbeck, S.; Nguyen, D.; Jenkins, M.; Grizzi, F.; Cobos, E.; Figueroa, J.A.; et al. Galectins in cancer: Carcinogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, F.C.; Chen, H.Y.; Kuo, C.C.; Sytwu, H.K. Role of galectins in tumors and in clinical immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.; Cummings, R.D. Galectin-1, a β-galactoside-binding lectin in Chinese hamster ovary cells. I. Physical and chemical characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 5198–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lella, S.; Ma, L.; Díaz Ricci, J.C.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Asher, S.A.; Álvarez, R.M.S. Critical role of the solvent environment in galectin-1 binding to the disaccharide lactose. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitt, M.A.; Massa, S.M.; Leffler, H.; Barondes, S.H. Isolation and Expression of a Gene Encoding L-14-II, a New Human Soluble Lactose-binding Lectin. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 10601–10606. [Google Scholar]

- Cederfur, C.; Salomonsson, E.; Nilsson, J.; Halim, A.; Öberg, C.T.; Larson, G.; Nilsson, U.J.; Leffler, H. Different affinity of galectins for human serum glycoproteins: Galectin-3 binds many protease inhibitors and acute phase proteins. Glycobiology 2008, 18, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koths, K.; Taylor, E.; Halenbeck, R.; Casipit, C.; Wang, A. Cloning and characterization of a human Mac-2-binding protein, a new member of the superfamily defined by the macrophage scavenger receptor cysteine-rich domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 14245–14249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huflejt, M.E.; Leffler, H. Galectin-4 in normal tissues and cancer. Glycoconj. J. 2003, 20, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidas, D.D.; Vatzaki, E.H.; Vorum, H.; Celis, J.E.; Madsen, P.; Acharya, K.R. Structural basis for the recognition of carbohydrates by human galectin- 7. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 13930–13940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ideo, H.; Matsuzaka, T.; Nonaka, T.; Seko, A.; Yamashita, K. Galectin-8-N-Domain Recognition Mechanism for Sialylated and Sulfated Glycans. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 11346–11355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagae, M.; Nishi, N.; Nakamura-Tsuruta, S.; Hirabayashi, J.; Wakatsuki, S.; Kato, R. Structural Analysis of the Human Galectin-9 N-terminal Carbohydrate Recognition Domain Reveals Unexpected Properties that Differ from the Mouse Orthologue. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 375, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heusschen, R.; Griffioen, A.W.; Thijssen, V.L. Galectin-9 in tumor biology: A jack of multiple trades. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2013, 1836, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J. A brief history of Charcot-Leyden crystal protein/galectin-10 research. Molecules 2018, 23, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, K.; Funahashi, T.; Matsukawa, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Nishizawa, H.; Kishida, K.; Matsuda, M.; Kuriyama, H.; Kihara, S.; Nakamura, T.; et al. Galectin-12, an Adipose-expressed Galectin-like Molecule Possessing Apoptosis-inducing Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 34089–34097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.Y.; Hsu, D.K.; Yu, L.; Ni, J.; Liu, F.T. Cell Cycle Regulation by Galectin-12, a New Member of the Galectin Superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 20252–20260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Than, N.G.; Balogh, A.; Romero, R.; Kárpáti, É.; Erez, O.; Szilágyi, A.; Kovalszky, I.; Sammar, M.; Gizurarson, S.; Matkó, J.; et al. Placental Protein 13 (PP13)—A placental immunoregulatory galectin protecting pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Wang, Y.; Si, Y.; Gao, J.; Song, C.; Cui, L.; Wu, R.; Tai, G.; Zhou, Y. Galectin-13, a different prototype galectin, does not bind β-galactosides and forms dimers via intermolecular disulfide bridges between Cys-136 and Cys-138. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 980. [Google Scholar]

- Than, N.G.; Romero, R.; Goodman, M.; Weckle, A.; Xing, J.; Dong, Z.; Xu, Y.; Tarquini, F.; Szilagyi, A.; Gal, P.; et al. A primate subfamily of galectins expressed at the maternal-fetal interface that promote immune cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 9731–9736. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).