1. Introduction

Pueraria lobata (wild.) Ohwi (hereinafter abbreviated as

P. lobata) is an important medicinal and edible plant, mainly distributed in East Asian countries, including China [

1]. In traditional Chinese medicine, the root of

P. lobata is the main medicinal component, also known as kudzu. A

Chinese Pharmacopeia dating back to 200 B.C. mentions the use of the roots of kudzu and their use in various treatments [

2]. Kudzu has long been used to treat fever, toxicosis, indigestion, alcoholism and other illnesses in the

Chinese Pharmacopoeia [

3]. The roots of

P. lobata are rich resources of natural product isoflavonoids, including genistein, formononetin, daidzein and puerarin (also called daidzein 8-C-glycoside). Among these isoflavonoids, the main bioactive components are puerarin and daidzein [

4,

5]. Modern pharmacological studies have shown that these two isoflavones protect the cardiovascular system, exert an anti-inflammatory effect and reduce the blood alcohol levels [

6,

7]. Puerarin is considered to be the main active isoflavone of

P. lobata and

P. thomsonii. It has biological activities against cardiovascular disease, and vascular hypertension and improves insulin sensitivity [

4,

8,

9]. Isoflavone synthesis is a branch of the flavonoid pathway. Puerarin is biosynthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway by the hydroxylation of liquiritigenin at the C-2 position to yield its isoflavonoid skeleton [

10] (

Figure 1). In the upstream pathway, phenylalanine is transformed into glycyrrhizin and naringin through the continuous action of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase (C4H), 4-coumaric acid CoA ligase (4CL), chalcone synthase (CHS) and chalcone isomerase (CHI) [

4,

11]. In the downstream pathway, Isoflavonoids are generated from liquiritigenin or naringenin under the hydroxylation, methylation and glycosylation by 2-hydroxyisoflavanone synthase (IFS), 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase (HIDH), methyltransferases, and glycosyltransferases, respectively [

4,

7].

Before the 2005 edition of the

Chinese Pharmacopoeia,

P. lobata and

P. thomsonii were regarded as Pueraria and as a source of traditional Chinese medicine. In the long-term process of introduction, cultivation and domestication, the names and plant species of

P. lobata and its varieties are confused in most areas and studies, resulting in the unclear resource location of

P. lobata and its varieties [

3]. In terms of composition, the root of

P. lobata usually contains a high content of puerarin, up to 60–70 mg/g, while the puerarin content of

P. thomsonii is usually less than 5 mg/g [

12]. In terms of genetic material, the genomes of the two kinds of

P. lobata have also changed greatly. At present, many research reports are available on the transcriptome and related isoflavone synthesis genes of

P. lobata or

P. thomsonii. Additionally, there are two reports on the genome of

P. thomsonii and

P. montana [

13,

14], but the data on the genome of

P. lobata have not been reported [

10]. The lack of reference genome information on

P. lobata hinders further investigation of potential genes in important biological processes related to isoflavone biosynthesis [

10,

15].

In this study, the leaves of P. lobata were chosen as the material, and the genome sequence of P. lobata was obtained and assembled by PacBio and Illumina Hiseq sequencing technology. After completing assembly and annotation, we explored the unique genes of isoflavones and puerarin metabolism in legumes through genome-wide comparison, gene family clustering, phylogenetic tree and other methods, and explored the relationship between puerarin-specific genes and special biological traits. The evolutionary status of P. lobata species was identified, and the genome evolutionary history of species and even the whole branch was traced. The study further revealed the pathway and mechanism of puerarin synthesis in P. lobata by a transcriptome and metabolome analysis. This research expected to provide reference data support for the comprehensive utilization and classification of medicinal plant resources of P. lobata and P. thomsonii.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, DNA Extraction and Genome Sequencing

The diploid

P. lobata were planted in an experimental medicinal botanical garden at Wuhan Polytechnic University (Longitude: 114.23855 latitude: 30.63535, Wuhan, China) and Luotian (31.021052, 115.595175). The roots of four cultivated varieties of

P. lobata with varying puerarin levels, PlobLT13, Plob53, Plob17, Plob19 and Plob25, were utilized for the transcriptome and metabolome analysis, and were marked as A, B, C, D and E, respectively, in this research (

Table S1). Root, stem, young leaves, flower and seeds of

P. lobata were collected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use for DNA and RNA extraction.

Genomic DNA was extracted from young leaves of P. lobata and used to construct Illumina DNA libraries according to the standard protocols provided by the Illumina HiSeq company (Novogene Biotech Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China). A PacBio library was constructed using a SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0 (PacBio, Menlo Park, CA, USA) and sequenced on a PacBio Sequel II system.

2.2. Genome Assembly and Quality Evaluation

All DNA extraction and sequencing procedures were performed by the Novogene Company (Tianjin, China) (

http://www.novogene.com/, accessed on 31 October 2022). The Hi-C library was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq PE150 platform. PacBio readings were utilized for de novo assembly, and Pilon v1.22 was used to polish them using Illumina data [

16]. The corrected contigs were further scaffolded into chromosomal-level genome via Hi-C. Hi-C technology obtained the interaction information between DNA fragments that were spatially connected, that is, DNA fragments that were physically distant, through special experimental techniques. Different contigs or scaffolds were divided into different chromosomes according to the probability of interaction within chromosomes being significantly higher than the probability of interaction between chromosomes. According to the same chromosome, the probability of interaction decreased with the increase in the interaction distance. Contigs or scaffolds of the same chromosome were sorted and oriented. Hifiasm software (v0.16.1) was used for the rapid construction of haplotype from the scratch assembly program of PacBio Hifi reads [

17,

18]. We used Samtools (v0.1.19) (

http://samtools.sourceforge.net/, accessed on 2 October 2022) and other tools to sort. The BWA (v0.7.8) comparison resulted in chromosome coordinates, removing duplicate reads, etc., conducting SNP calling, and filtering and counting the original results. BUSCO (v5.2.1) was applied to evaluate the completeness of assembly by mapping the genome sequence to the embryophyta_odb10 database [

19]. CGEMA (v2.5) was used to evaluate the integrity of the assembled genome. The conservative genes (248 genes) existing in 6 eukaryotic model organisms were selected to form the core gene library, and the assembled genome evaluated with tblastn, genewise and geneid software [

20]. Based on the K-mer algorithm, Illumina sequencing data and Merqury software (

https://github.com/marbl/merqury, accessed on 25 June 2022) were used to evaluate genome quality, which did not need to reference genome [

21]. The genome assembly software utilized in this work is listed in

Table S2.

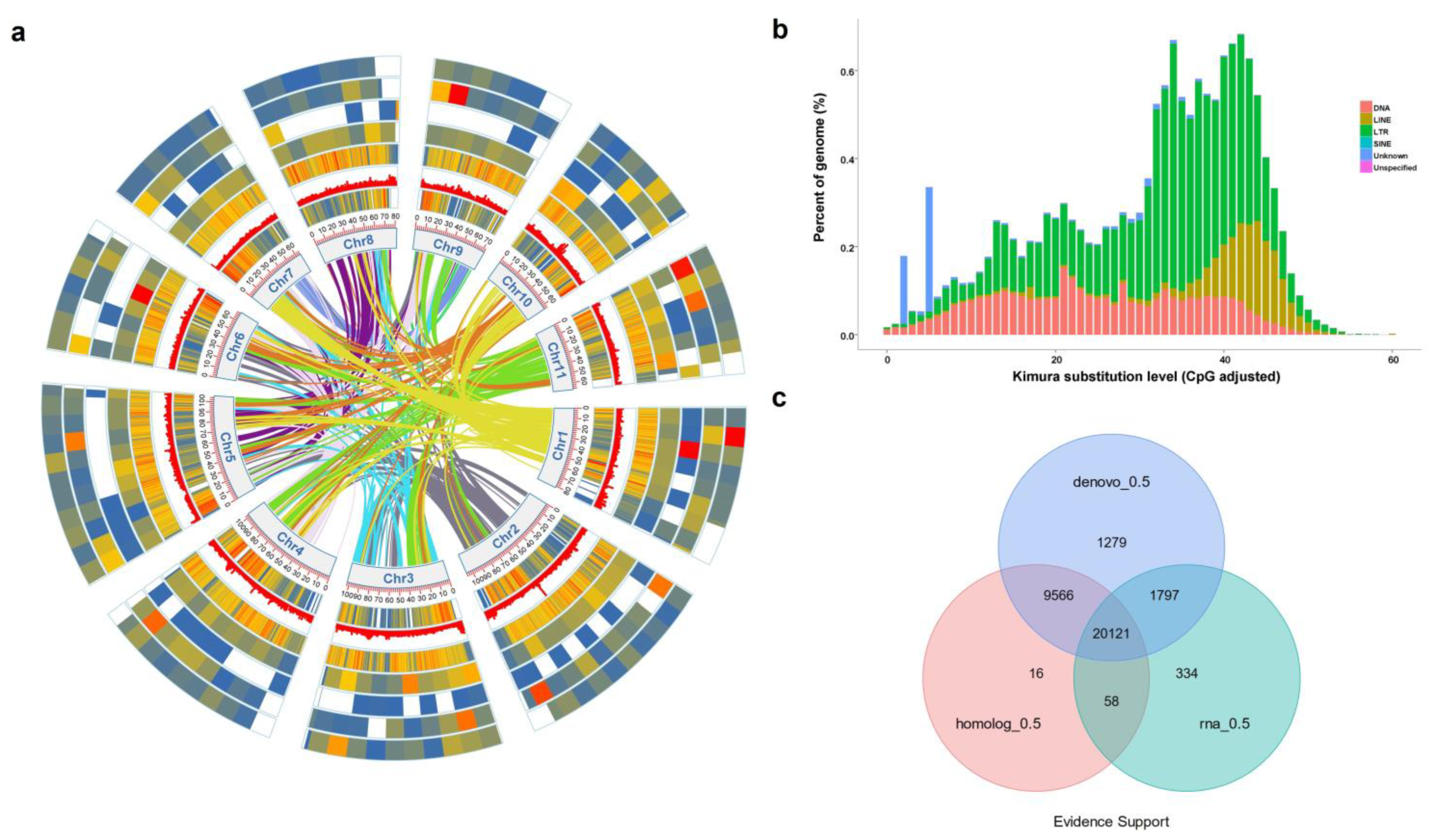

2.3. RNA-seq Data

Trinity (v2.1.1) was used to construct transcriptome read assemblies for genome annotation. To optimize the genome annotation, RNA-Seq reads from various tissues were aligned to the fasta genome using Hisat (v2.0.4) and TopHat (v2.0.11) with default parameters to identify exons regions, and splice sites. The alignment results were then utilized as input for genome-based transcript assembly using Stringtie (v1.3.3)/Cufflinks (v2.2.1) with default settings. The non-redundant reference gene collection was created by combining genes predicted by three ways with EvidenceModeler (EVM, v1.1.1), adding masked transposable elements as input into gene prediction and employing PASA (Program to Assemble Spliced Alignment) terminal exon support. Individual families of interest were hand-picked by relevant specialists for further human curation.

2.4. Genome Annotation

In our repeat annotation workflow, we used a combination technique based on homology alignment and de novo search to find entire genome repetitions. Tandem Repeat was retrieved using ab initio prediction and TRF (

http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html, accessed on 25 June 2022). The Repbase (

http://www.girinst.org/repbase, assessed on 2 October 2022) database was used for homolog prediction, and it employed RepeatMasker (

http://www.repeatmasker.org/, assessed on 2 October 2022) software and its in-house scripts (RepeatProteinMask) with default settings to extract repeat regions. Then, using LTR FINDER (

http://tlife.fudan.edu.cn/ltrfinder/, assessed on 2 October 2022), RepeatScout (

http://www.repeatmasker.org/, accessed on 2 October 2022) and RepeatModeler (

http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler.html, assessed on 2 October 2022) with default parameters, all repeat sequences with lengths >100 bp and gap ‘N’ less than 5% comprised the raw transposable element (TE) library. For DNA-level repeat detection, a bespoke library (a mix of Repbase and our Denovo TE library processed by uclust to create a non-redundant library) was submitted to RepeatMasker.

To annotate gene models, structural annotation of the genome was employed, which includes AB initio prediction, homology-based prediction and RNA-Seq aided prediction.

The homologous protein sequences were obtained from NCBI. Protein sequences were matched to the genome using TBLASTN (v2.2.26; E-value 105), and the matching proteins were aligned to the homologous genome sequences for accurate spliced alignments using GeneWise (v2.4.1) software, which predicted the gene structure present in each protein region.

Augustus (v3.2.3), Geneid (v1.4), Genescan (v1.0), GlimmerHMM (v3.04) and SNAP (29 November 2013) were applied in our automated gene prediction pipeline for Ab initio gene prediction.

By matching the protein sequences to the Swiss-Prot database using BLASTP (with a threshold of E-value ≤ 10−5), gene functions were given based on the best match. InterPro Scan 70 (v5.31) was used to annotate the motifs and domains by searching against publicly available databases such as PRINTS, Pfam, ProDom, PANTHER, SMRT and PROSITE. Each gene’s Gene Ontology (GO) ID was allocated based on the corresponding InterPro entry. We predicted protein function by transferring annotations from the nearest BLAST hit (E-value 10−5) in the Swiss-Prot 20 database and DI-AMOND (v0.8.22)/BLAST hit (E-value 10−5) in the NR 20 database. We also mapped the gene collection to a Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and determined which genes were the best matches.

The tRNAs were predicted using the tRNAscan-SE tool (

http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/, assessed on 2 October 2022). Because rRNAs are highly conserved, we used relative species’ rRNA sequences as references and used BLAST to predict rRNA sequences. Other ncRNAs, including as miRNAs and snRNAs, were discovered by searching the Rfam database with the default parameters of the infernal program (

http://infernal.janelia.org/, assessed on 2 October 2022).

2.5. Gene Family and Phylogenomic Analysis

To identify gene family groups, protein-coding genes from 14 species,

Pueraria_lobata,

Arabidopsis_thaliana,

Glycine_max,

Medicago_truncatula,

Arachis_duranensis,

Arachis_hypogaea,

Phaseolus_vulgaris,

Cajanus_cajan,

Cicer_arietinum,

Vigna_radiata,

Trifolium_pratense,

Lupinus_albus,

Vigna_unguiculata and

Vigna_angularis were analyzed (

Table S3).

The longest transcript in the coding region was retained to remove redundancy, and the genes encoding polypeptides shorter than 30 amino acids were also abandoned to exclude putative fragmented genes. The similarity relation between all species’ protein sequencings was obtained by All-against-all BLASTP (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi/, assessed on 2 October 2022) [

22] search with a cut-off (E-value = 10

−5). The alignment with high-scoring segment pairs was conjoined for each gene pair by solar [

23]. A hierarchical clustering algorithm was applied to group orthologs and paralogs using OrthoMCL software (

http://orthomcl.org/orthomcl/, assessed on 2 October 2022) [

24] with the inflation parameter 1.5.

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

Single-copy orthologous genes were aligned with Muscle (

http://www.drive5.com/muscle/, assessed on 2 October 2022) [

25]. A super alignment matrix was created by concatenating all alignment findings. RAxML was used to generate ML phylogenetic trees based on multiple sequence alignments [

26].

2.7. Divergence Times Estimate

Divergence times were calculated using single-copy orthologous by the MCMC Tree program of PAML (

http://abacus.gene.ucl.ac.uk/software/paml.html, assessed on 2 October 2022) [

27] with main parameters (burn-in = 10,000, sample-number = 100,000, sample-frequency = 2). The calibration times were taken from the TimeTree database (

http://www.timetree.org/, assessed on 2 October 2022) [

28].

2.8. Gene Family Expansion and Contraction

To identify gene family evolution as a random birth and death process model, where gene family either expands or contracts per gene per million years independently along each lineage of the phylogenetic tree, the maximum likelihood model originally implemented in the software package CAFE (

http://sourceforge.net/projects/cafehahnlab/, assessed on 2 October 2022) was applied to compare the cluster size differences (gain or loss) between the ancestor and each species [

29]. A

p-value of 0.05 was used to identify families where the size of the species has changed considerably. To determine the relevance of changes in gene family size in each branch, the phylogenetic tree topology and branch lengths were considered.

2.9. Positively Selected Genes

Single-copy orthologous genes were aligned with Muscle (

http://www.drive5.com/muscle/, assessed on 2 October 2022) [

25]. Likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) based on the branch-site model of PAML were used to detect positive selection sites with

A. thaliana as the foreground branch [

30]. The

p-values were computed using the χ

2 statistic and corrected for multiple testing by the false discovery rate (FDR) method. This analysis calculated Ka/Ks through a likelihood ratio test to detect the probability of positive selection.

2.10. Whole-Genome Duplication Inference

An all-against-all BLASTP (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi/, assessed on 2 October 2022) was used with a threshold (E-value = 10

−5) to identify the putative paralogous genes in, and orthologous genes between, each species. Syntenic blocks were performed based on the detected homologous gene pairs using MCscanX (

http://chibba.pgml.uga.edu/mcscan2/, assessed on 2 October 2022) [

22,

30]. Each duplicate gene pairs of syntenic block were aligned with Muscle [

25], and then back-translated to their coding sequences. The four-fold synonymous third-codon transversion rates (4DTv) of syntenic blocks were calculated and were used to detect WGD events. The distribution of 4DTv values was plotted. The synonymous substitution (Ks) values for pairwise comparisons were estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method implemented in the codeml program of the PAML package [

27].

2.11. WGCNA Analysis

A Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) was performed by the Novogene online tools to discover critical regulatory genes in the correlation between puerarin production and gene expression in various species (

https://magic.novogene.com/customer/, assessed on 2 October 2022). The module eigengene was defined as the first major component of a specific module and was then used to describe the expression profile of module genes in each sample. The Pearson correlations between the eigengenes of each module and the abundance of flavonoids were performed using R package ggplot2.

2.12. Metabolome Analysis

The roots of different

P. lobata samples were used for the metabonomic analysis (

Table S1). The metabolome analysis was completed by Metware Biotech Co., Ltd. (

www.metware.cn. Wuhan, China) according to the methods of Cheng [

31]. The freeze-dried roots were crushed using a mixer mill (mm 400, retsch) with a zirconia bead for 1.5 min at 30 Hz. Then, 100 mg powder was weighted and extracted overnight at 4 °C with 1.0 mL 70% aqueous methanol. Following centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min, the extracts were absorbed (CNWBOND Carbon-GCB SPE Cartridge, 250 mg, 3 mL; ANPEL, Shanghai, China) and filtrated (SCAA-104, 0.22 μm pore size; ANPEL, Shanghai, China) before the LC-MS analysis.

The sample extracts were analyzed using an LC-ESI-MS/MS system (HPLC, Shim-pack UFLC SHIMADZU CBM30A system,

www.s himadzu.com.cn/ (assessed on 2 October 2022); MS, Applied Biosystems 6500 Q TRAP,

www.a ppliedbiosys-tems.com.cn/, assessed on 2 October 2022). The analytical conditions were as follows, HPLC: column, Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 C18 (1.8 µm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm); solvent system, water (0.04% acetic acid): acetonitrile (0.04% acetic acid); gradient program, 95:5

v/v at 0 min, 5:95

v/v at 11.0 min, 5:95

v/v at 12.0 min, 95:5

v/v at 12.1 min, 95:5

v/v at 15.0 min; flow rate, 0.40 mL/min; temperature, 40 °C; injection volume: 2 μL. The effluent was alternatively connected to an ESI-triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (Q TRAP)-MS.

The ESI-Q TRAP-MS/MS. LIT and triple quadrupole (QQQ) scans were acquired on a triple quadrupole-linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Q TRAP), API 6500 Q TRAP LC/MS/MS System, equipped with an ESI Turbo Ion-Spray interface, operating in a positive ion mode, and controlled by Analyst 1.6.3 software (AB Sciex).

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Excel 2021 and SPSS (22.0) were used to process experimental data. Chen’s approach was used to process the heat map, Circos, chromosomal collinearity and related network diagram content analysis using the TB-tools software. Duncan’s test was performed to see whether there were any significant changes (

p ≤ 0.05) [

32]. The correlation network was created with the OmicStudio tools, which may be found at

https://www.omicstudio.cn/tool (assessed on 2 October 2022). The positive correlation criterion was greater than or equal to 0.5, the negative correlation threshold was less than or equal to −0.5 and the

p-value threshold was less than 0.5. R version 3.6.1 and igraph1.2.6 [

31]. Every experiment had three biological duplicates.

4. Discussion

P. lobata is an important medicinal and edible homologous plant that is widely cultivated in Asian countries [

33]. The stem skin fiber of

P. lobata is often used as a raw material for weaving and papermaking in the industry [

3].

P. lobata has been considered as an important traditional Chinese medicine and homologous food for hundreds of years, with economic market potential. Its roots are not only nutritious, but also have many pharmacological properties, including flavonoids and isoflavones, which are widely used to treat and prevent various diseases [

10,

34]. In the query of specimens, it is found that the identification of

P. lobata,

P. thomsonii and

P. montana in most specimens is confusing, especially in the older specimens, where many of them identify

P. thomsonii, and

P. montana as

P. lobata. At present, only

P. lobata and

P. thomsonii are used for traditional Chinese medicine and food, respectively [

35]. The root tubers of

P. lobata show a higher isoflavone content, especially puerarin, which is called kudzu in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. However, the root tubers of

P. thomsonii show a higher starch content but a lower isoflavone content, and therefore it is called starch kudzu, which is generally used for food [

36]. The genome sequence, transcriptome and metabolite analyses reported in the study might help understand the biosynthesis of these natural products.

Previously, Shang reported the first high-quality chromosome-scale genome of

P. thomsonii [

13]. The genome size was ~1.37 GB, with a contig N50 of 593.7 kb. The genome structural annotation resulted in 869.33 Mb repeat regions (62.7% of the genome) and 45,270 protein-coding genes. A total of 572 genes that were upregulated in the puerarin biosynthesis pathway were identified, and 235 candidate genes were further enriched by transcriptome data [

13]. As another wild species of Pueraria, the genome size of

P. montana was ~978.59 Mb, with contig N50 of 80.18 Mb. A comparative genomics analysis showed that the genome size of

P. montana was smaller than that of

P. thomsonii because of fewer repetitive sequences and duplicated genes [

14]. Compared with the previous two species of pueraria, the genome of

P. lobata was smaller and had fewer repetitive sequences and duplicated genes: the genome size of

P. lobata was only ~939 Mb. The genome reported in

P. lobata shows that the repetitive sequences accounted for 63.50% of the

P. lobata genome, and a total of 33,171 coding genes were predicted, of which 97.34% could predict the function. A total of 224 genes related to flavonoid metabolism were enriched in this study, including 40 genes related to the isoflavone synthesis.

P. lobata and

P. montana were both wild species of pueraria, with less artificial cultivation and intervention. However, because of the low content of medicinal ingredients,

P. montana was not used as traditional Chinese medicine [

3,

36].

P. thomsonii was more edible than medicinal in evolution, with faster growth speed and stronger edible roots, due to the artificial introduction and the change in the cultivation environment. The growth of

P. lobata was slower, and it had higher isoflavone content. These findings may be related to genome duplication and changes in evolution.

Although

P. lobata and

P. thomsonii both were recorded in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia as having high medicinal value, modern studies have confirmed large differences between the two varieties in material basis and efficacy [

37]. Shang’s study showed that

P. lobata had higher amounts of syringaresinol-4′O-glucoside and disinapoyl glucoside, and

P. thomsonii had higher amounts of glycycoumarin and 2-hydroxyadenosine. It was suggested that the specific compounds found in a particular variety could be used to differentiate the Pueraria varieties [

36]. We detected 223 flavonoids in

P. lobata, including 42 isoflavones. Besides the daidzein and puerarin commonly found in Pueraria plants, more isoflavones were also detected, such as daidzein-7-O-(2′’-benzoyl) rhamnoside, daidzein-7-O-Glucoside-4′-O-Apioside, genistein-7-O-(6′’-malonyl) glucoside, licoisoflavone B, calycosin-7-O-glucoside and other substances. These substances not only enriched isoflavones in

P. lobata, but also increased the content of its medicinal active ingredients. These new active substances, which were different from those in

P. thomsonii, might be related to the expansion of the glycosidase gene in the

P. lobata genome.

As an isoflavonoid, puerarin is biosynthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway by the hydroxylation of liquiritigenin at the C-2 position to yield its isoflavonoid skeleton. However, the reaction step for C-glucosylation in puerarin biosynthesis remains an enigma [

4]. Based on the labeling studies in

P. lobata roots, the chalcone substrate (isoliquiritigenin), but not the isoflavone substrate (daidzein), was purported to be an intermediate in the pathway to puerarin [

38]. Wang’s study revealed that PlUGT43 possessed an activity for the C-glucosylation of daidzein to puerarin, and it showed activity with the isoflavones daidzein and genistein, but displayed no activity towards other potential acceptors, including flavonoids [

4]. In this study, six unique PlUGT43 homologous genes were retrieved from the genome of

P. lobata, and no 2-hydroxyisoflavanone 8-C-glucoside was found in the metabolites. This also confirmed that puerarin was synthesized mainly from the glycation of daidzein (

Figure 1).

Besides the influence of structural genes in the metabolic pathway on puerarin synthesis, TFs are also important switches for regulating isoflavone synthesis. However, reports about the role of TFs in the regulation of puerarin synthesis are rare [

4,

39]. The TF regulation of the flavonoid pathway has been extensively studied in many plant species, such as

Z. mays,

A. thaliana,

M. domestica and so on [

40,

41,

42]. Among these, TFs of MYB, bHLH and WD40 function individually or collaborate as an MBW complex to control multiple enzymatic steps in the flavonoid pathway [

43]. The biosynthesis of flavonoids or isoflavonoids has been extensively studied in model plants, but not in non-model plants due to the lack of genomic and genetic information. Shen found that the transcription levels of

PlMYB1,

PlHLH3-4 and

PlWD40-1 genes were closely correlated with isoflavonoid accumulation profiles in different tissues and cell cultures of kudzu [

39]. The over-expression of

PlMYB1 in

A. thaliana significantly increased the accumulation of anthocyanins in leaves and pro-anthocyanidins in seeds by activating

AtDFR,

AtANR and

AtANS genes [

39]. The combined analysis of the genome and transcriptome of

P. thomsonii indicated that 41

PlbHLHs showed root-specific expression patterns, and seven of them exhibited upregulated expression after MeJA treatment. Using qRT-PCR validation, five puerarin synthesis-related genes had a similar expression pattern as the seven

PlbHLH genes in response to MeJA within 24 h [

13]. In this study, 68 TFs related to isoflavone and puerarin synthesis were obtained in the

P. lobata genome, including two

bHLH, six

MYB and four

WRKY. The data suggested that these key TFs might be involved in the expression regulation of the structural genes of the puerarin synthesis pathway.