Structure-Guided Strategies of Targeted Therapies for Patients with EGFR-Mutant Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

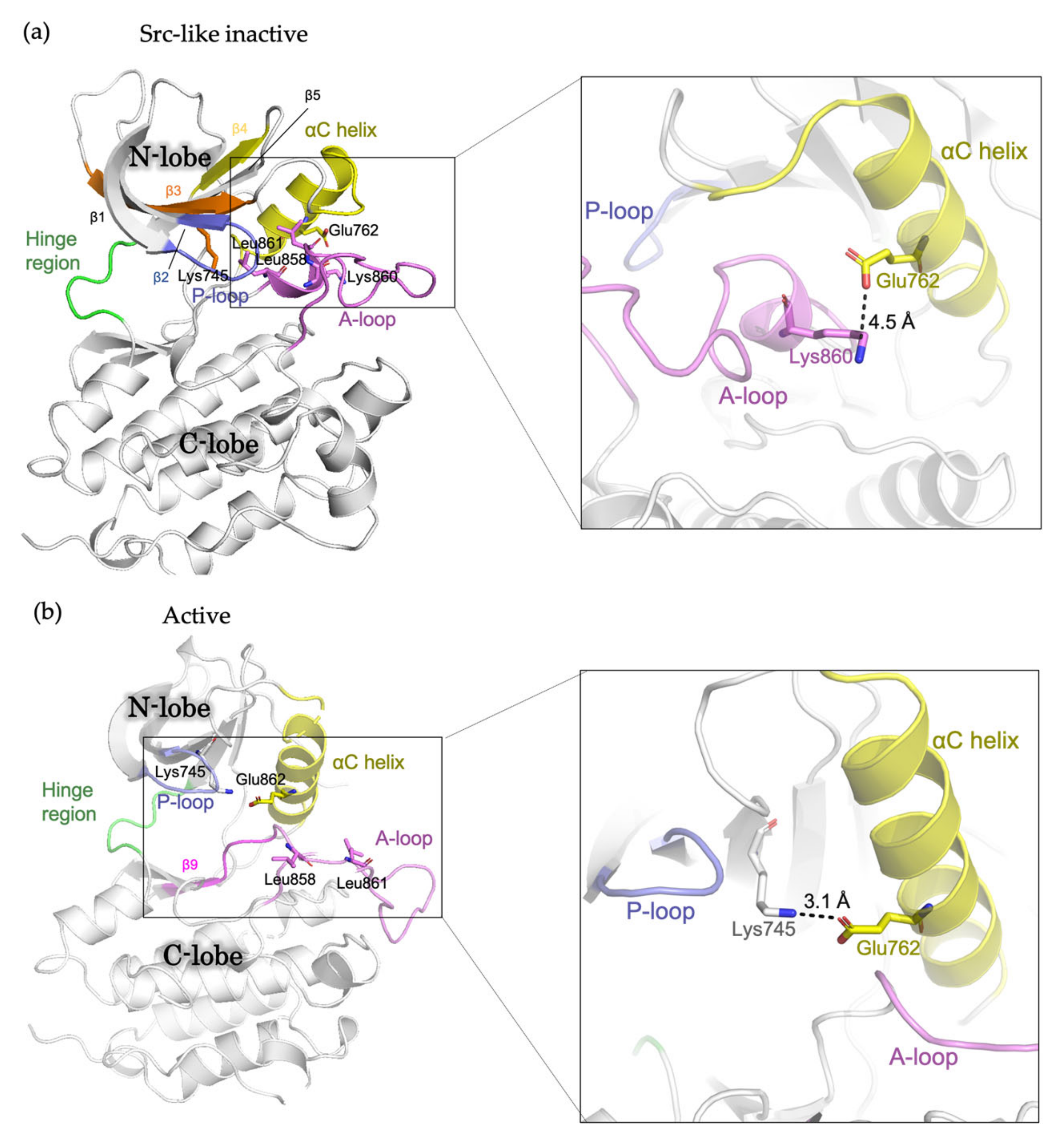

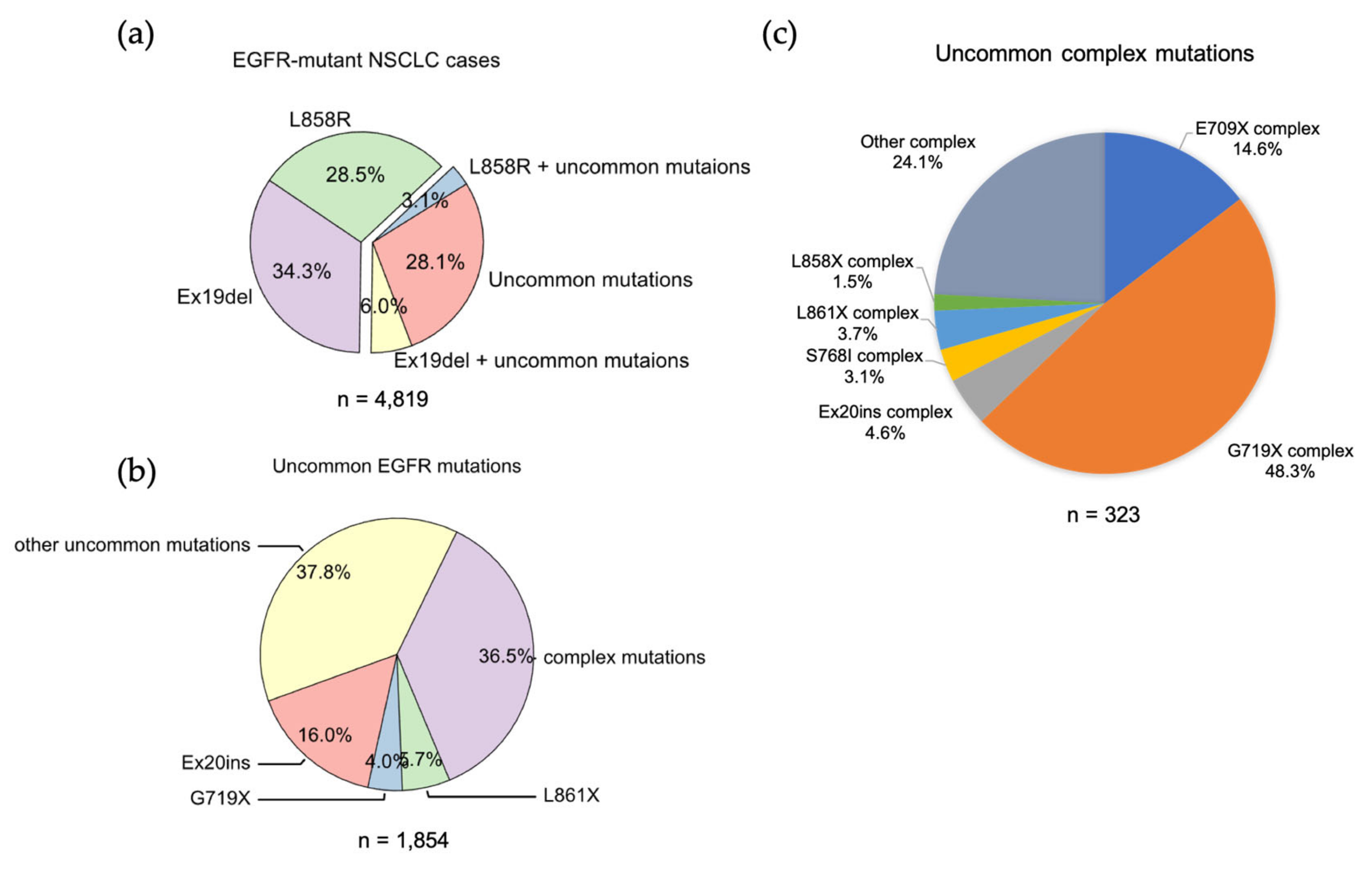

2. The Conformational States of EGFR Kinase Domain

3. Targeted Therapy for NSCLC Patients with EGFR Mutations

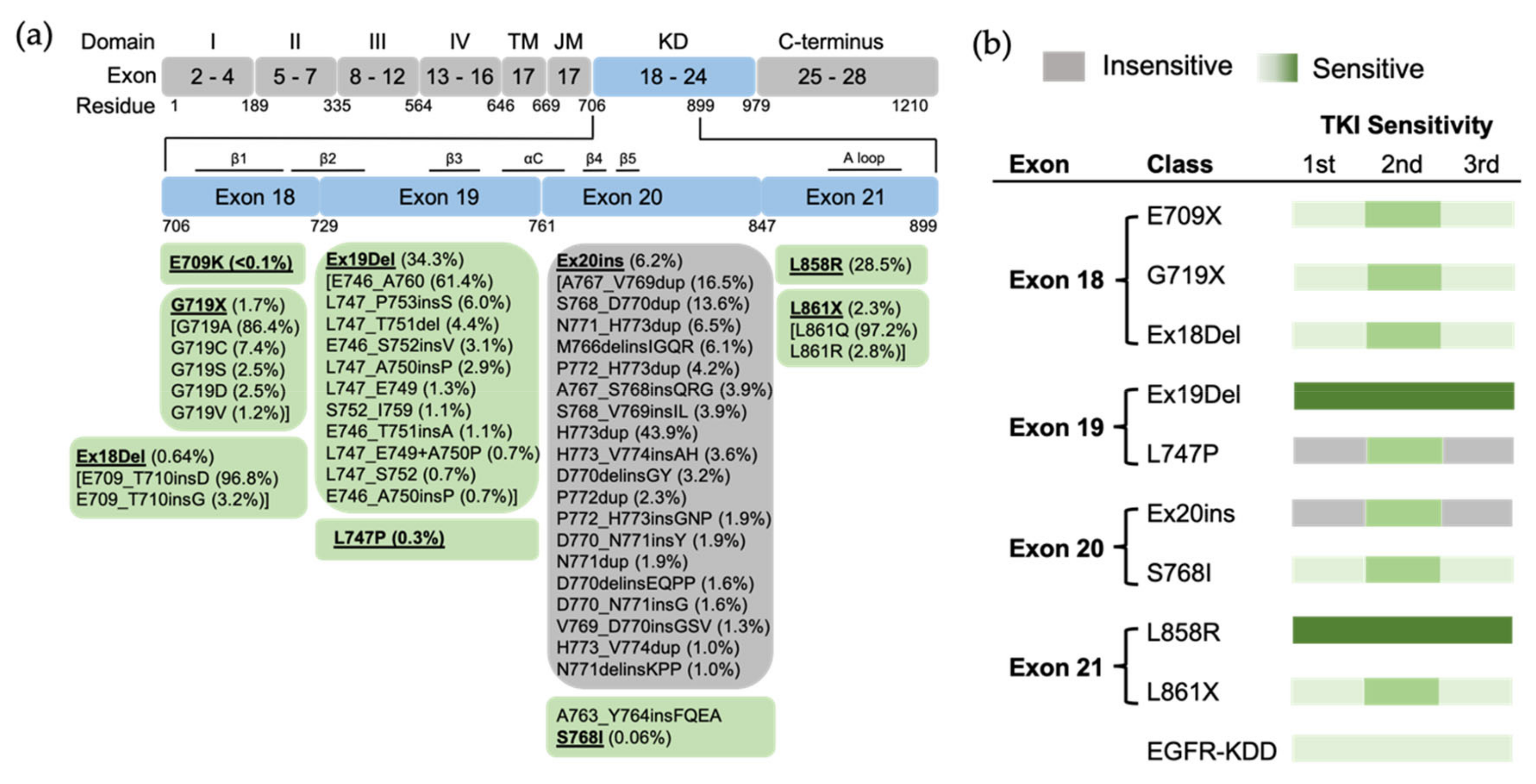

3.1. Classical Mutations

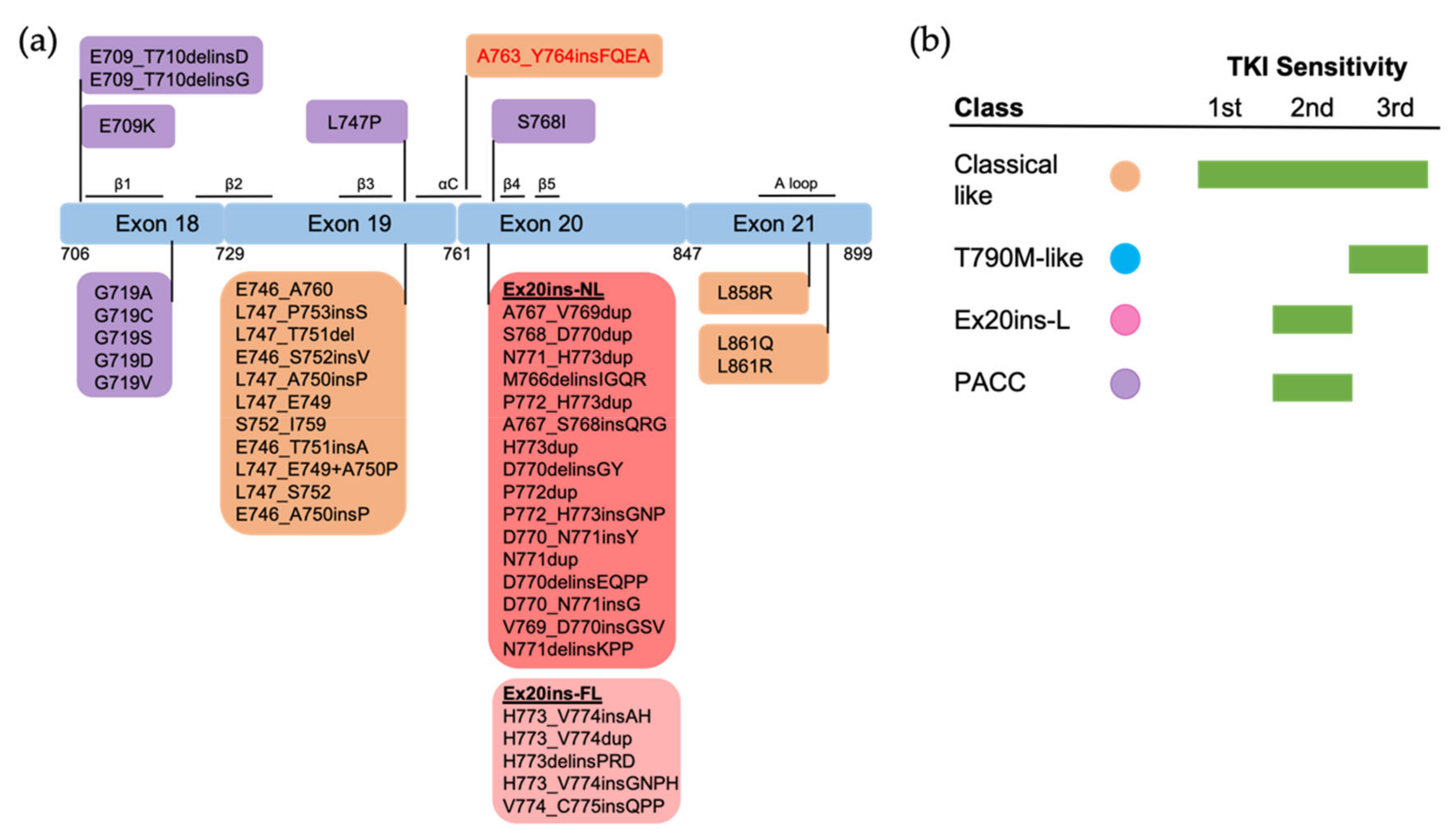

3.2. Uncommon EGFR Mutations

3.2.1. Exon 18 Mutations

3.2.2. Exon 19 Mutations

3.2.3. Exon 20 Mutations

3.2.4. Exon 21 Mutations

3.2.5. EGFR Kinase Domain Duplication

3.2.6. Uncommon Complex Mutations

4. Conclusions and Perspective

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusk, C.M.; Watza, D.; Dyson, G.; Craig, D.; Ratliff, V.; Wenzlaff, A.S.; Lonardo, F.; Bollig-Fischer, A.; Bepler, G.; Purrington, K.; et al. Profiling the Mutational Landscape in Known Driver Genes and Novel Genes in African American Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4300–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gillette, M.A.; Satpathy, S.; Cao, S.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Vasaikar, S.V.; Krug, K.; Petralia, F.; Li, Y.; Liang, W.W.; Reva, B.; et al. Proteogenomic Characterization Reveals Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cell 2020, 182, 200–225.e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Teo, A.S.M.; Amer, L.B.; Sherbaf, F.G.; Tan, C.Q.; Alvarez, J.J.S.; Lu, B.; Lim, J.Q.; Takano, A.; et al. Genomic landscape of lung adenocarcinoma in East Asians. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckx, B.; Shahi, R.B.; Smeets, D.; De Brakeleer, S.; Decoster, L.; Van Brussel, T.; Galdermans, D.; Vercauter, P.; Decoster, L.; Alexander, P.; et al. The genomic landscape of nonsmall cell lung carcinoma in never smokers. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 3207–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigematsu, H.; Lin, L.; Takahashi, T.; Nomura, M.; Suzuki, M.; Wistuba, I.I.; Fong, K.M.; Lee, H.; Toyooka, S.; Shimizu, N.; et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.; Joubert, P.; Ansari-Pour, N.; Zhao, W.; Hoang, P.H.; Lokanga, R.; Moye, A.L.; Rosenbaum, J.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Martinez-Jimenez, F.; et al. Genomic and evolutionary classification of lung cancer in never smokers. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1348–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, T.J.; Bell, D.W.; Sordella, R.; Gurubhagavatula, S.; Okimoto, R.A.; Brannigan, B.W.; Harris, P.L.; Haserlat, S.M.; Supko, J.G.; Haluska, F.G.; et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez, J.G.; Janne, P.A.; Lee, J.C.; Tracy, S.; Greulich, H.; Gabriel, S.; Herman, P.; Kaye, F.J.; Lindeman, N.; Boggon, T.J.; et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science 2004, 304, 1497–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mok, T.S.; Wu, Y.L.; Thongprasert, S.; Yang, C.H.; Chu, D.T.; Saijo, N.; Sunpaweravong, P.; Han, B.; Margono, B.; Ichinose, Y.; et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, R.; Carcereny, E.; Gervais, R.; Vergnenegre, A.; Massuti, B.; Felip, E.; Palmero, R.; Garcia-Gomez, R.; Pallares, C.; Sanchez, J.M.; et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, K.M.; Berger, M.B.; Mendrola, J.M.; Cho, H.S.; Leahy, D.J.; Lemmon, M.A. EGF activates its receptor by removing interactions that autoinhibit ectodomain dimerization. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arkhipov, A.; Shan, Y.; Das, R.; Endres, N.F.; Eastwood, M.P.; Wemmer, D.E.; Kuriyan, J.; Shaw, D.E. Architecture and membrane interactions of the EGF receptor. Cell 2013, 152, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Srinivasan, S.; Regmi, R.; Lin, X.; Dreyer, C.A.; Chen, X.; Quinn, S.D.; He, W.; Coleman, M.A.; Carraway, K.L., 3rd; Zhang, B.; et al. Ligand-induced transmembrane conformational coupling in monomeric EGFR. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanetti-Domingues, L.C.; Korovesis, D.; Needham, S.R.; Tynan, C.J.; Sagawa, S.; Roberts, S.K.; Kuzmanic, A.; Ortiz-Zapater, E.; Jain, P.; Roovers, R.C.; et al. The architecture of EGFR’s basal complexes reveals autoinhibition mechanisms in dimers and oligomers. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Gureasko, J.; Shen, K.; Cole, P.A.; Kuriyan, J. An allosteric mechanism for activation of the kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cell 2006, 125, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Bharill, S.; Karandur, D.; Peterson, S.M.; Marita, M.; Shi, X.; Kaliszewski, M.J.; Smith, A.W.; Isacoff, E.Y.; Kuriyan, J. Molecular basis for multimerization in the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Elife 2016, 5, e14107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, S.R.; Roberts, S.K.; Arkhipov, A.; Mysore, V.P.; Tynan, C.J.; Zanetti-Domingues, L.C.; Kim, E.T.; Losasso, V.; Korovesis, D.; Hirsch, M.; et al. EGFR oligomerization organizes kinase-active dimers into competent signalling platforms. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Ognjenovic, J.; Karandur, D.; Miller, K.; Merk, A.; Subramaniam, S.; Kuriyan, J. A molecular mechanism for the generation of ligand-dependent differential outputs by the epidermal growth factor receptor. Elife 2021, 10, e73218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.H.; Boggon, T.J.; Li, Y.; Woo, M.S.; Greulich, H.; Meyerson, M.; Eck, M.J. Structures of lung cancer-derived EGFR mutants and inhibitor complexes: Mechanism of activation and insights into differential inhibitor sensitivity. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Eastwood, M.P.; Zhang, X.; Kim, E.T.; Arkhipov, A.; Dror, R.O.; Jumper, J.; Kuriyan, J.; Shaw, D.E. Oncogenic mutations counteract intrinsic disorder in the EGFR kinase and promote receptor dimerization. Cell 2012, 149, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foster, S.A.; Whalen, D.M.; Ozen, A.; Wongchenko, M.J.; Yin, J.; Yen, I.; Schaefer, G.; Mayfield, J.D.; Chmielecki, J.; Stephens, P.J.; et al. Activation Mechanism of Oncogenic Deletion Mutations in BRAF, EGFR, and HER2. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruan, Z.; Kannan, N. Altered conformational landscape and dimerization dependency underpins the activation of EGFR by alphaC-beta4 loop insertion mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E8162–E8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Red Brewer, M.; Yun, C.H.; Lai, D.; Lemmon, M.A.; Eck, M.J.; Pao, W. Mechanism for activation of mutated epidermal growth factor receptors in lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E3595–E3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, X.E.; Ayaz, P.; Zhu, S.J.; Zhao, P.; Liang, L.; Zhang, C.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Li, J.L.; Choi, H.G.; Huang, X.; et al. Structural Basis of AZD9291 Selectivity for EGFR T790M. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 8502–8511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.V.; Bell, D.W.; Settleman, J.; Haber, D.A. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaux, J.P.; Le, X.; Vijayan, R.S.K.; Hicks, J.K.; Heeke, S.; Elamin, Y.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Udagawa, H.; Skoulidis, F.; Tran, H.; et al. Structure-based classification predicts drug response in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Nature 2021, 597, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Wu, Y.L.; Schuler, M.; Sebastian, M.; Popat, S.; Yamamoto, N.; Zhou, C.; Hu, C.P.; O’Byrne, K.; Feng, J.; et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6): Analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Yang, G.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Hao, X.; Xing, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. EGFR Exon 18 Mutations in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Real-World Study on Diverse Treatment Patterns and Clinical Outcomes. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 713483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, T.; Taus, A.; Arriola, E.; Aguado, C.; Domine, M.; Rueda, A.G.; Calles, A.; Cedres, S.; Vinolas, N.; Isla, D.; et al. Clinical Activity of Afatinib in Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring Uncommon EGFR Mutations: A Spanish Retrospective Multicenter Study. Clin. Lung Cancer 2020, 21, 428–436.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Li, S.; Deng, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhong, Y.; He, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic impact of atypical EGFR mutations in completely resected lung adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 177, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, K.; Rangachari, D.; VanderLaan, P.A.; Kobayashi, S.S.; Costa, D.B. Clinical Benefit of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Advanced Lung Cancer with EGFR-G719A and Other Uncommon EGFR Mutations. Oncologist 2021, 26, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanazu, M.; Mori, M.; Kimura, M.; Nishino, K.; Shiroyama, T.; Nagatomo, I.; Ihara, S.; Komuta, K.; Suzuki, H.; Hirashima, T.; et al. Effectiveness of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with uncommon EGFR mutations: A multicenter observational study. Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, D.E.; Mayer, M.; Gagan, J.; von Itzstein, M.S. Systemic and Intracranial Efficacy of Osimertinib in EGFR L747P-Mutant NSCLC: Case Report. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2022, 3, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, X.; Li, P.; Qi, C.; Ling, Y. EGFR L747P mutation in one lung adenocarcinoma patient responded to afatinib treatment: A case report. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, E802–E805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Mao, X.; Ding, L. A rare EGFR mutation L747P conferred therapeutic efficacy to both ge fi tinib and osimertinib: A case report. Lung Cancer 2020, 150, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meador, C.B.; Sequist, L.V.; Piotrowska, Z. Targeting EGFR Exon 20 Insertions in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Recent Advances and Clinical Updates. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2145–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Xu, F.; Xia, B.; Zhu, V.W.; Nagasaka, M.; Yang, Y.; et al. EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in Chinese advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients: Molecular heterogeneity and treatment outcome from nationwide real-world study. Lung Cancer 2020, 145, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Ichihara, E.; Sakakibara-Konishi, J.; Zenke, Y.; Takeuchi, S.; Morise, M.; Hotta, K.; Sato, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Tanimoto, A.; et al. A phase I/II study of osimertinib in EGFR exon 20 insertion mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2021, 162, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhenova, L.; Minchom, A.; Viteri, S.; Bauml, J.M.; Ou, S.I.; Gadgeel, S.M.; Trigo, J.M.; Backenroth, D.; Li, T.; Londhe, A.; et al. Comparative clinical outcomes for patients with advanced NSCLC harboring EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations and common EGFR mutations. Lung Cancer 2021, 162, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Jian, H.; Tong, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, F.; Shao, Y.W.; Zhao, X. Variability of EGFR exon 20 insertions in 24 468 Chinese lung cancer patients and their divergent responses to EGFR inhibitors. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Mitsudomi, T. Not all epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer are created equal: Perspectives for individualized treatment strategy. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banno, E.; Togashi, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Chiba, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Terashima, M.; de Velasco, M.A.; Sakai, K.; Fujita, Y.; et al. Sensitivities to various epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors of uncommon epidermal growth factor receptor mutations L861Q and S768I: What is the optimal epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor? Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yasuda, H.; Park, E.; Yun, C.H.; Sng, N.J.; Lucena-Araujo, A.R.; Yeo, W.L.; Huberman, M.S.; Cohen, D.W.; Nakayama, S.; Ishioka, K.; et al. Structural, biochemical, and clinical characterization of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 20 insertion mutations in lung cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 216ra177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vasconcelos, P.; Gergis, C.; Viray, H.; Varkaris, A.; Fujii, M.; Rangachari, D.; VanderLaan, P.A.; Kobayashi, I.S.; Kobayashi, S.S.; Costa, D.B. EGFR-A763_Y764insFQEA Is a Unique Exon 20 Insertion Mutation That Displays Sensitivity to Approved and In-Development Lung Cancer EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2020, 1, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.P.; Zhang, Y.K.; Westover, D.; Yan, Y.; Qiao, H.; Huang, V.; Du, Z.; Smith, J.A.; Ross, J.S.; Miller, V.A.; et al. On-target Resistance to the Mutant-Selective EGFR Inhibitor Osimertinib Can Develop in an Allele-Specific Manner Dependent on the Original EGFR-Activating Mutation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3341–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ikemura, S.; Yasuda, H.; Matsumoto, S.; Kamada, M.; Hamamoto, J.; Masuzawa, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Manabe, T.; Arai, D.; Nakachi, I.; et al. Molecular dynamics simulation-guided drug sensitivity prediction for lung cancer with rare EGFR mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10025–10030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, Z.; Brown, B.P.; Kim, S.; Ferguson, D.; Pavlick, D.C.; Jayakumaran, G.; Benayed, R.; Gallant, J.N.; Zhang, Y.K.; Yan, Y.; et al. Structure-function analysis of oncogenic EGFR Kinase Domain Duplication reveals insights into activation and a potential approach for therapeutic targeting. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Arkhipov, A.; Kim, E.T.; Pan, A.C.; Shaw, D.E. Transitions to catalytically inactive conformations in EGFR kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 7270–7275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.L.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lee, K.H.; Nakagawa, K.; Niho, S.; Tsuji, F.; Linke, R.; Rosell, R.; Corral, J.; et al. Dacomitinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ARCHER 1050): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1454–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, A.; Janne, P.A.; Mok, T.; Peters, S. Overcoming therapy resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soria, J.C.; Ohe, Y.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Reungwetwattana, T.; Chewaskulyong, B.; Lee, K.H.; Dechaphunkul, A.; Imamura, F.; Nogami, N.; Kurata, T.; et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.C.; Chewaskulyong, B.; Lee, K.H.; Dechaphunkul, A.; Sriuranpong, V.; Imamura, F.; Nogami, N.; Kurata, T.; Okamoto, I.; Zhou, C.; et al. Osimertinib versus Standard of Care EGFR TKI as First-Line Treatment in Patients with EGFRm Advanced NSCLC: FLAURA Asian Subset. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramalingam, S.S.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Planchard, D.; Cho, B.C.; Gray, J.E.; Ohe, Y.; Zhou, C.; Reungwetwattana, T.; Cheng, Y.; Chewaskulyong, B.; et al. Overall Survival with Osimertinib in Untreated, EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Dong, X.; Yang, C.T.; Song, Y.; Chang, G.C.; Lu, Y.; Pan, H.; Chiu, C.H.; et al. Efficacy of Aumolertinib (HS-10296) in Patients with Advanced EGFR T790M+ NSCLC: Updated Post-National Medical Products Administration Approval Results from the APOLLO Registrational Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Feng, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yang, N.; Wu, L.; Liao, W.; Zhong, D.; et al. Safety, Clinical Activity, and Pharmacokinetics of Alflutinib (AST2818) in Patients with Advanced NSCLC With EGFR T790M Mutation. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagasaka, M.; Zhu, V.W.; Lim, S.M.; Greco, M.; Wu, F.; Ou, S.I. Beyond Osimertinib: The Development of Third-Generation EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors for Advanced EGFR+ NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 740–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eno, M.S.; Brubaker, J.D.; Campbell, J.E.; De Savi, C.; Guzi, T.J.; Williams, B.D.; Wilson, D.; Wilson, K.; Brooijmans, N.; Kim, J.; et al. Discovery of BLU-945, a Reversible, Potent, and Wild-Type-Sparing Next-Generation EGFR Mutant Inhibitor for Treatment-Resistant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 9662–9677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, C.; Beyett, T.S.; Jang, J.; Feng, W.W.; Bahcall, M.; Haikala, H.M.; Shin, B.H.; Heppner, D.E.; Rana, J.K.; Leeper, B.A.; et al. An allosteric inhibitor against the therapy-resistant mutant forms of EGFR in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, T.J.; Bell, J.L.; Bruce, J.P.; Doherty, G.J.; Galvin, M.; Green, M.F.; Hunter-Zinck, H.; Kumari, P.; Lenoue-Newton, M.L.; Li, M.M.; et al. AACR Project GENIE: 100,000 Cases and Beyond. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 2044–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Ercan, D.; Chen, L.; Yun, C.H.; Li, D.; Capelletti, M.; Cortot, A.B.; Chirieac, L.; Iacob, R.E.; Padera, R.; et al. Novel mutant-selective EGFR kinase inhibitors against EGFR T790M. Nature 2009, 462, 1070–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuler, M.; Yang, J.C.; Park, K.; Kim, J.H.; Bennouna, J.; Chen, Y.M.; Chouaid, C.; De Marinis, F.; Feng, J.F.; Grossi, F.; et al. Afatinib beyond progression in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer following chemotherapy, erlotinib/gefitinib and afatinib: Phase III randomized LUX-Lung 5 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Capelletti, M.; Nafa, K.; Yun, C.H.; Arcila, M.E.; Miller, V.A.; Ginsberg, M.S.; Zhao, B.; Kris, M.G.; Eck, M.J.; et al. EGFR exon 19 insertions: A new family of sensitizing EGFR mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baek, J.H.; Sun, J.M.; Min, Y.J.; Cho, E.K.; Cho, B.C.; Kim, J.H.; Ahn, M.J.; Park, K. Efficacy of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer except both exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R: A retrospective analysis in Korea. Lung Cancer 2015, 87, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohsaka, S.; Nagano, M.; Ueno, T.; Suehara, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Shimada, N.; Takahashi, K.; Suzuki, K.; Takamochi, K.; Takahashi, F.; et al. A method of high-throughput functional evaluation of EGFR gene variants of unknown significance in cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaan6566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, J.; Jin, B.; Chu, T.; Dong, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Lou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; et al. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring uncommon EGFR mutations: A real-world study in China. Lung Cancer 2016, 96, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamirat, M.Z.; Koivu, M.; Elenius, K.; Johnson, M.S. Structural characterization of EGFR exon 19 deletion mutation using molecular dynamics simulation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.P.; Zhang, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Finneran, P.; Yan, Y.; Du, Z.; Kim, J.; Hartzler, A.L.; LeNoue-Newton, M.L.; Smith, A.W.; et al. Allele-specific activation, enzyme kinetics, and inhibitor sensitivities of EGFR exon 19 deletion mutations in lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2206588119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truini, A.; Starrett, J.H.; Stewart, T.; Ashtekar, K.; Walther, Z.; Wurtz, A.; Lu, D.; Park, J.H.; DeVeaux, M.; Song, X.; et al. The EGFR Exon 19 Mutant L747-A750>P Exhibits Distinct Sensitivity to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6382–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Jiang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, C.; Chen, X.; Ren, S.; Li, X.; Zhou, C. The impact of EGFR exon 19 deletion subtypes on clinical outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.H.; Mengwasser, K.E.; Toms, A.V.; Woo, M.S.; Greulich, H.; Wong, K.K.; Meyerson, M.; Eck, M.J. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2070–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, H.A.; Pao, W. Targeted therapies: Afatinib--new therapy option for EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 551–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, J.; Peled, N.; Schokrpur, S.; Wolner, M.; Rotem, O.; Girard, N.; Aboubakar Nana, F.; Derijcke, S.; Kian, W.; Patel, S.; et al. UNcommon EGFR Mutations: International Case Series on Efficacy of Osimertinib in Real-Life Practice in First-LiNe Setting (UNICORN). J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Togashi, Y.; Yatabe, Y.; Mizuuchi, H.; Jangchul, P.; Kondo, C.; Shimoji, M.; Sato, K.; Suda, K.; Tomizawa, K.; et al. EGFR Exon 18 Mutations in Lung Cancer: Molecular Predictors of Augmented Sensitivity to Afatinib or Neratinib as Compared with First- or Third-Generation TKIs. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5305–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minari, R.; Leonetti, A.; Gnetti, L.; Zielli, T.; Ventura, L.; Bottarelli, L.; Lagrasta, C.; La Monica, S.; Petronini, P.G.; Alfieri, R.; et al. Afatinib therapy in case of EGFR G724S emergence as resistance mechanism to osimertinib. Anticancer Drugs 2021, 32, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wu, J.; Ye, F. Meningeal metastasis patients with EGFR G724S who develop resistance to osimertinib benefit from the addition of afatinib. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 2188–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Huang, Y.; Gan, J.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, L. Emergence of EGFR G724S After Progression on Osimertinib Responded to Afatinib Monotherapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, e36–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Jiang, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, H. Afatinib as a Potential Therapeutic Option for Patients with NSCLC With EGFR G724S. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2021, 2, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Ning, W.W.; Li, J.; Huang, J.A. Exon 19 L747P mutation presented as a primary resistance to EGFR-TKI: A case report. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E542–E546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, J. Non-small cell lung cancer harboring a rare EGFR L747P mutation showing intrinsic resistance to both gefitinib and osimertinib (AZD9291): A case report. Thorac. Cancer 2018, 9, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Stebbing, J.; Peng, L. Afatinib treatment in a lung adenocarcinoma patient harboring a rare EGFR L747P mutation. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2022, 18, 1436–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, W.; Jiang, B.; Han, C.; Ye, F.; Wu, J. Case Report: Dacomitinib is effective in lung adenocarcinoma with rare EGFR mutation L747P and brain metastases. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 863771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, T.; Uchibori, K.; Araki, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Ma, B.; Kanada, R.; Seto, Y.; Oh-Hara, T.; Koike, S.; Ariyasu, R.; et al. Microsecond-timescale MD simulation of EGFR minor mutation predicts the structural flexibility of EGFR kinase core that reflects EGFR inhibitor sensitivity. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlaender, A.; Subbiah, V.; Russo, A.; Banna, G.L.; Malapelle, U.; Rolfo, C.; Addeo, A. EGFR and HER2 exon 20 insertions in solid tumours: From biology to treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Shih, J.Y. Not All EGFR Exon 20 Insertions Are Created Equal. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2020, 1, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Xing, R.; Li, M.; Feng, J.; Sun, R.; Wei, B.; Guo, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, H. Real-world clinical treatment outcomes in Chinese non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 949304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Sequist, L.V.; Geater, S.L.; Tsai, C.M.; Mok, T.S.; Schuler, M.; Yamamoto, N.; Yu, C.J.; Ou, S.H.; Zhou, C.; et al. Clinical activity of afatinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring uncommon EGFR mutations: A combined post-hoc analysis of LUX-Lung 2, LUX-Lung 3, and LUX-Lung 6. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beau-Faller, M.; Prim, N.; Ruppert, A.M.; Nanni-Metellus, I.; Lacave, R.; Lacroix, L.; Escande, F.; Lizard, S.; Pretet, J.L.; Rouquette, I.; et al. Rare EGFR exon 18 and exon 20 mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer on 10 117 patients: A multicentre observational study by the French ERMETIC-IFCT network. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, J.; Sima, C.S.; Rodriguez, K.; Busby, N.; Nafa, K.; Ladanyi, M.; Riely, G.J.; Kris, M.G.; Arcila, M.E.; Yu, H.A. Epidermal growth factor receptor exon 20 insertions in advanced lung adenocarcinomas: Clinical outcomes and response to erlotinib. Cancer 2015, 121, 3212–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janning, M.; Suptitz, J.; Albers-Leischner, C.; Delpy, P.; Tufman, A.; Velthaus-Rusik, J.L.; Reck, M.; Jung, A.; Kauffmann-Guerrero, D.; Bonzheim, I.; et al. Treatment outcome of atypical EGFR mutations in the German National Network Genomic Medicine Lung Cancer (nNGM). Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, P.J.; Tsui, D.W.; Rosenfeld, N.; Chin, T.M. EGFR exon 20 insertion A763-Y764insFQEA and response to erlotinib--Letter. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 2614–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kobayashi, I.S.; Viray, H.; Rangachari, D.; Kobayashi, S.S.; Costa, D.B. EGFR-D770>GY and Other Rare EGFR Exon 20 Insertion Mutations with a G770 Equivalence Are Sensitive to Dacomitinib or Afatinib and Responsive to EGFR Exon 20 Insertion Mutant-Active Inhibitors in Preclinical Models and Clinical Scenarios. Cells 2021, 10, 3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elamin, Y.Y.; Robichaux, J.P.; Carter, B.W.; Altan, M.; Tran, H.; Gibbons, D.L.; Heeke, S.; Fossella, F.V.; Lam, V.K.; Le, X.; et al. Poziotinib for EGFR exon 20-mutant NSCLC: Clinical efficacy, resistance mechanisms, and impact of insertion location on drug sensitivity. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 754–767.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udagawa, H.; Hasako, S.; Ohashi, A.; Fujioka, R.; Hakozaki, Y.; Shibuya, M.; Abe, N.; Komori, T.; Haruma, T.; Terasaka, M.; et al. TAS6417/CLN-081 Is a Pan-Mutation-Selective EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor with a Broad Spectrum of Preclinical Activity against Clinically Relevant EGFR Mutations. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 2233–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonzalvez, F.; Vincent, S.; Baker, T.E.; Gould, A.E.; Li, S.; Wardwell, S.D.; Nadworny, S.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, W.S.; et al. Mobocertinib (TAK-788): A Targeted Inhibitor of EGFR Exon 20 Insertion Mutants in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 1672–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J.L.; Alexander, M.; Itchins, M.; Wright, G.M.; Kao, S.; Hughes, B.G.M.; Pavlakis, N.; Clarke, S.; Gill, A.J.; Ainsworth, H.; et al. EGFR Exon 20 Insertion Mutations: Clinicopathological Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2021, 22, e859–e869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popat, S.; Hsia, T.C.; Hung, J.Y.; Jung, H.A.; Shih, J.Y.; Park, C.K.; Lee, S.H.; Okamoto, T.; Ahn, H.K.; Lee, Y.C.; et al. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Activity in Patients with NSCLC Harboring Uncommon EGFR Mutations: A Retrospective International Cohort Study (UpSwinG). Oncologist 2022, 27, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Reva, B.; Yu, H.; Rusch, V.W.; Rizvi, N.A.; Kris, M.G.; Arcila, M.E. Clinical and in vivo evidence that EGFR S768I mutant lung adenocarcinomas are sensitive to erlotinib. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014, 9, e73–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leventakos, K.; Kipp, B.R.; Rumilla, K.M.; Winters, J.L.; Yi, E.S.; Mansfield, A.S. S768I Mutation in EGFR in Patients with Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11, 1798–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuiper, J.L.; Hashemi, S.M.; Thunnissen, E.; Snijders, P.J.; Grunberg, K.; Bloemena, E.; Sie, D.; Postmus, P.E.; Heideman, D.A.; Smit, E.F. Non-classic EGFR mutations in a cohort of Dutch EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients and outcomes following EGFR-TKI treatment. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niogret, J.; Coudert, B.; Boidot, R. Primary Resistance to Afatinib in a Patient with Lung Adenocarcinoma Harboring Uncommon EGFR Mutations: S768I and V769L. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018, 13, e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, J.H.; Lim, S.H.; An, H.J.; Kim, K.H.; Park, K.U.; Kang, E.J.; Choi, Y.H.; Ahn, M.S.; Lee, M.H.; Sun, J.M.; et al. Osimertinib for Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring Uncommon EGFR Mutations: A Multicenter, Open-Label, Phase II Trial (KCSG-LU15-09). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, I.J.Z.; Stensgaard, S.; Helland, A.; Ekman, S.; Mellemgaard, A.; Hansen, K.H.; Cicenas, S.; Koivunen, J.; Gronberg, B.H.; Sorensen, B.S.; et al. Osimertinib in non-small cell lung cancer with uncommon EGFR-mutations: A post-hoc subgroup analysis with pooled data from two phase II clinical trials. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.H.; Yang, C.T.; Shih, J.Y.; Huang, M.S.; Su, W.C.; Lai, R.S.; Wang, C.C.; Hsiao, S.H.; Lin, Y.C.; Ho, C.L.; et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Treatment Response in Advanced Lung Adenocarcinomas with G719X/L861Q/S768I Mutations. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallant, J.N.; Sheehan, J.H.; Shaver, T.M.; Bailey, M.; Lipson, D.; Chandramohan, R.; Red Brewer, M.; York, S.J.; Kris, M.G.; Pietenpol, J.A.; et al. EGFR Kinase Domain Duplication (EGFR-KDD) Is a Novel Oncogenic Driver in Lung Cancer That Is Clinically Responsive to Afatinib. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Xue, X.; Ou, Q.; Wu, X.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X.; You, M.; Shao, Y.W.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Clinical outcomes of EGFR kinase domain duplication to targeted therapies in NSCLC. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 2677–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, D.B. Kinase inhibitor-responsive genotypes in EGFR mutated lung adenocarcinomas: Moving past common point mutations or indels into uncommon kinase domain duplications and rearrangements. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2016, 5, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, D.; Xie, Y.; Jin, C.; Qiu, J.; Hou, T.; Du, H.; Chen, S.; Xiang, J.; Shi, X.; Liu, J. The landscape of kinase domain duplication in Chinese lung cancer patients. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, C.S.; Wu, D.; Smith, C.; Martins, R.G.; Pritchard, C.C. Durable Response to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy in a Lung Cancer Patient Harboring Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tandem Kinase Domain Duplication. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, e97-99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, D.; Li, X.L.; Wu, B.; Zheng, X.B.; Wang, W.X.; Chen, H.F.; Dong, Y.Y.; Xu, C.W.; Fang, M.Y. A Novel Oncogenic Driver in a Lung Adenocarcinoma Patient Harboring an EGFR-KDD and Response to Afatinib. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.D.; Gao, H.; Qin, S.M.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, Q.F. Osimertinib is an effective epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor choice for lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor exon 18-25 kinase domain duplication: Report of two cases. Anticancer Drugs 2022, 33, e486–e490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taek Kim, J.; Zhang, W.; Lopategui, J.; Vail, E.; Balmanoukian, A. Patient with Stage IV NSCLC and CNS Metastasis with EGFR Exon 18-25 Kinase Domain Duplication with Response to Osimertinib as a First-Line Therapy. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, R.; Li, J.; Jin, Z.; Lu, Y.; Shao, Y.W.; Li, W.; Zhao, G.; Xia, Y. Osimertinib confers potent binding affinity to EGFR kinase domain duplication. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 2884–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Shih, J.Y. Effectiveness of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on uncommon E709X epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 6137–6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheng, C.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zheng, D.; Zheng, S.; Shen, X.; Sun, Y.; et al. EGFR Exon 18 Mutations in East Asian Patients with Lung Adenocarcinomas: A Comprehensive Investigation of Prevalence, Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Prognosis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EGFR TKI | Selectivity | Binding Mode | Status in NSCLC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st-generation | Erlotinib | WT EGFR | Reversible | FDA-approved |

| Gefitinib | WT EGFR | Reversible | FDA-approved | |

| 2nd-generation | Afatinib | WT EGFR | Irreversible | FDA-approved |

| Dacomitinib | WT EGFR | Irreversible | FDA-approved | |

| 3rd-generation | Osimertinib (AZD9291) | Mutant EGFR | Irreversible | FDA-approved |

| Aumolertinib (HS-10296) | Mutant EGFR | Irreversible | Approved in China [55] | |

| Alflutinib (AST2818) | Mutant EGFR | Irreversible | Approved in China [56] | |

| 4th-generation | JBJ-09-063 | Mutant EGFR | Reversible | Under investigation [59] |

| BLU-945 | Mutant EGFR | Reversible | Under investigation [58] | |

| E709X | Partner Mutation | Count | G719X | Partner Mutation | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E709A | G719A | 12 | G719C | S768I | 43 |

| E709K | G719A | 11 | G719A | S768I | 24 |

| E709A | G719R | 8 | G719S | S768I | 14 |

| E709A | G719C | 3 | G719A | L861Q | 12 |

| E709K | G719S | 3 | G719S | L861Q | 11 |

| E709K | G719C | 2 | G719A | R776H | 6 |

| E709V | G719C | 2 | G719A | L833V | 5 |

| E709V | G719S | 1 | G719S | S768N | 3 |

| E709A | L861R | 1 | G719S | R776H | 3 |

| E709A | L861Q | 1 | G719D | L861Q | 2 |

| Ex20ins | Partner Mutation | Count | L861X | Partner Mutation | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N771_H773dup | V845L | 2 | L861Q | S720F | 3 |

| D770delinsEQPL | H773Y | 1 | L861Q | S768I | 2 |

| D770delinsEL | N771Y | 1 | L861R | S768I | 1 |

| D770_V774dup | Q791E | 1 | L861R | P1073T | 1 |

| D770_P772dup | H773Y | 1 | L861Q | R776H | 1 |

| D770_N771insY | S1030L | 1 | L861Q | R776C | 1 |

| D770_N771insG | N771Y | 1 | L861Q | L838V | 1 |

| A767_V769dup | R836C | 1 | L861Q | L833F | 1 |

| A767_S768insQRG | V765L | 1 | L861Q | L747F | 1 |

| H773delinsQI | N771H | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hesilaiti, N.; Xia, Q.; Cui, H.; Fan, N.; Xu, X. Structure-Guided Strategies of Targeted Therapies for Patients with EGFR-Mutant Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13020210

Du Z, Sun J, Zhang Y, Hesilaiti N, Xia Q, Cui H, Fan N, Xu X. Structure-Guided Strategies of Targeted Therapies for Patients with EGFR-Mutant Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Biomolecules. 2023; 13(2):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13020210

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Zhenfang, Jinghan Sun, Yunkai Zhang, Nigaerayi Hesilaiti, Qi Xia, Heqing Cui, Na Fan, and Xiaofang Xu. 2023. "Structure-Guided Strategies of Targeted Therapies for Patients with EGFR-Mutant Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer" Biomolecules 13, no. 2: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13020210