Scrutinizing Stator Rotation in the Bacterial Flagellum: Reconciling Experiments and Switching Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

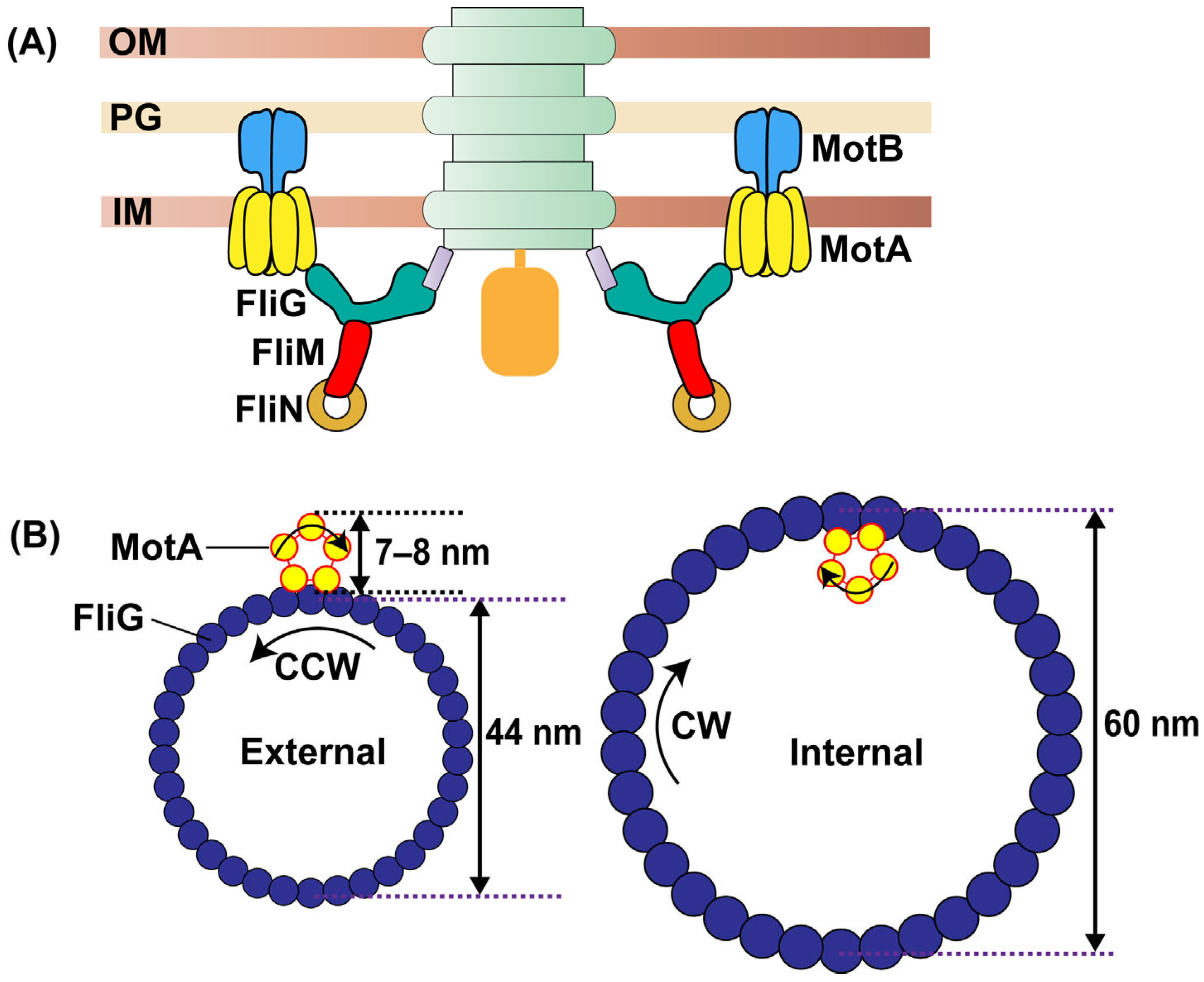

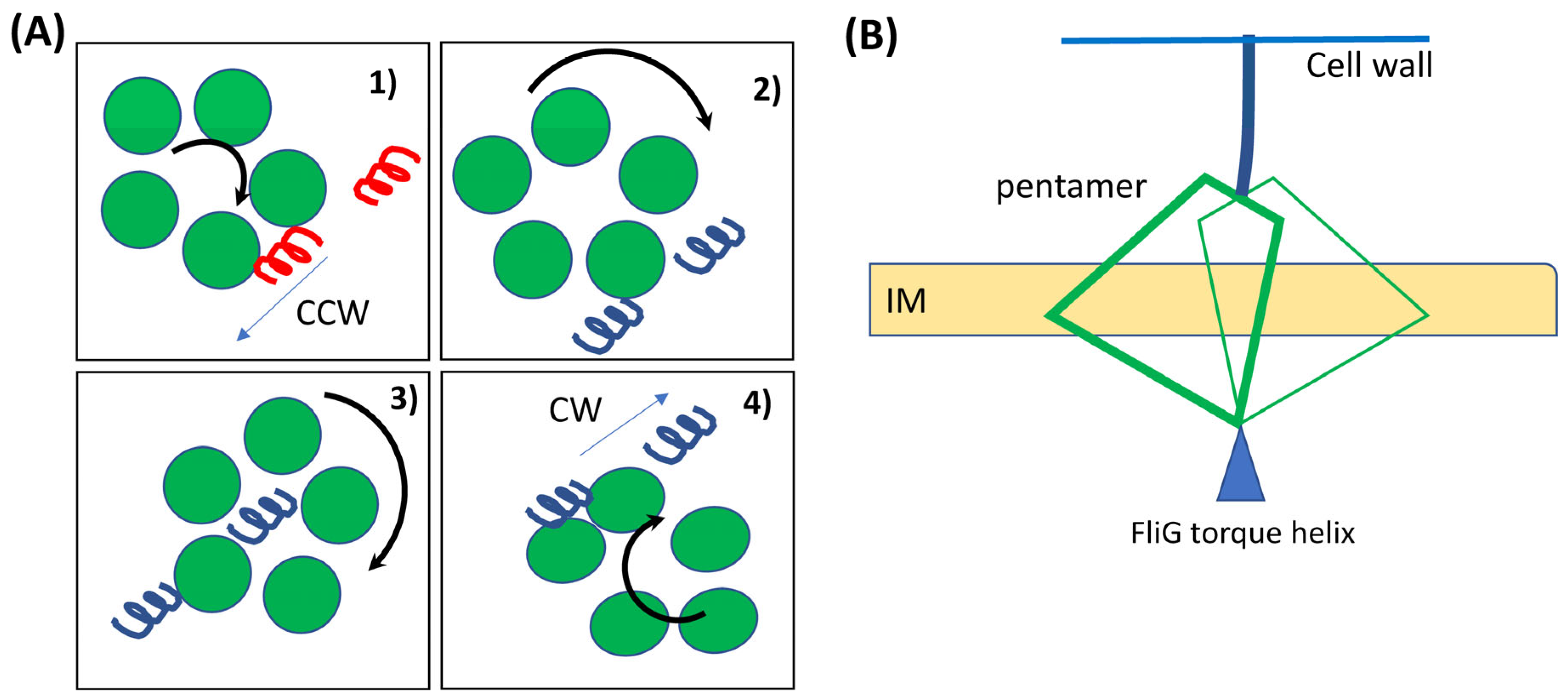

2. Stator Structure and Operation

3. Evidence for Stator Rotation and the Derivative Switching Model

4. Assumptions in the Stator Function Models and Future Directions

4.1. MotB Plugs and the PGBD

4.2. FliG Ring Expansion

5. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manson, M.D.; Nan, B.; Lele, P.P.; Liu, J.; Duncan, T.M. Editorial: Biological rotary nanomotors. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1012681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhams, G.H.; Armitage, J.P. Making sense of it all: Bacterial chemotaxis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, N.; Berg, H.C. Bacterial motility: Machinery and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 20, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.C.; Anderson, R.A. Bacteria Swim by Rotating their Flagellar Filaments. Nature 1973, 245, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.C. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003, 72, 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, M.D.; Tedesco, P.; Berg, H.C.; Harold, F.M.; Van der Drift, C. A protonmotive force drives bacterial flagella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 3060–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Hicks, D.B.; Henkin, T.M.; Guffanti, A.A.; Powers, B.D.; Zvi, L.; Uematsu, K.; Krulwich, T.A. MotPS is the stator-force generator for motility of Alkaliphilic Bacillus, and its homologue is a second functional Mot in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 1035–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, M.D.; Tedesco, P.M.; Berg, H.C. Energetics of flagellar rotation in bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 1980, 138, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, Y.; Kojima, S.; Kato, H.; Nishioka, N.; Kawagishi, I.; Homma, M. Putative channel components for the fast-rotating sodium-driven flagellar motor of a marine bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 5104–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, N.; Imae, Y. Na+-driven flagellar motors of an alkalophilic Bacillus strain YN-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 10577–10581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lele, P.P.; Hosu, B.G.; Berg, H.C. Dynamics of mechanosensing in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 11839–11844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belas, R. Biofilms, flagella, and mechanosensing of surfaces by bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, R.; Gupta, R.; Lele, T.P.; Lele, P.P. A Skeptic’s Guide to Bacterial Mechanosensing. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leanid, L.; Esteban, L.M.; Remy, C.; Victor, S. Flagellum-Mediated Mechanosensing and RflP Control Motility State of Pathogenic Escherichia coli. mBio 2020, 11, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Braun, T.F.; Blair, D.F. Motility Protein Complexes in the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 261, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa, Y.; Berry, R.M. Bacterial flagellar motor. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 41, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S.A.; Blair, D.F. Charged residues of the rotor protein FliG essential for torque generation in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 266, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Blair, D.F. Residues of the cytoplasmic domain of MotA essential for torque generation in the bacterial flagellar motor. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 273, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lloyd, S.A.; Blair, D.F. Electrostatic interactions between rotor and stator in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnab, R.M. Genetics and biogenesis of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1992, 26, 131–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamino, T.; Kinoshita, M.; Namba, K. Directional Switching Mechanism of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.K.; Ginsburg, M.A.; Crovace, C.; Donohoe, M.; Stock, D. Structure of the torque ring of the flagellar motor and the molecular basis for rotational switching. Nature 2010, 466, 996–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, A.; Miyata, T.; Makino, F.; Kinoshita, M.; Minamino, T.; Imada, K.; Kato, T.; Namba, K. Native flagellar MS ring is formed by 34 subunits with 23-fold and 11-fold subsymmetries. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosu, B.G.; Nathan VS, J.; Berg, H.C. Internal and external components of the bacterial flagellar motor rotate as a unit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4783–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.; Furlong, E.J.; Deme, J.C.; Nord, A.L.; Caesar, J.J.E.; Chevance, F.F.V.; Berry, R.M.; Hughes, K.T.; Lea, S.M. Molecular structure of the intact bacterial flagellar basal body. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Makino, F.; Miyata, T.; Horváth, P.; Namba, K. Structure of the native supercoiled flagellar hook as a universal joint. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevance, F.F.V.; Hughes, K.T. Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, C.; Chang, S.; Wu, H.; Wang, T.; Liang, H.; Gao, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Structural basis of assembly and torque transmission of the bacterial flagellar motor. Cell 2021, 184, 2665–2679.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Makino, F.; Miyata, T.; Minamino, T.; Kato, T.; Namba, K. Structure of the molecular bushing of the bacterial flagellar motor. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Fong, Y.H.; Deme, J.C.; Furlong, E.J.; Kuhlen, L.; Lea, S.M. Symmetry mismatch in the MS-ring of the bacterial flagellar rotor explains the structural coordination of secretion and rotation. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Branch, R.W.; Hosu, B.G.; Berg, H.C. Adaptation at the output of the chemotaxis signalling pathway. Nature 2012, 484, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lele, P.P.; Branch, R.W.; Nathan VS, J.; Berg, H.C. Mechanism for adaptive remodeling of the bacterial flagellar switch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 20018–20022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branch, R.W.; Sayegh, M.N.; Shen, C.; Nathan VS, J.; Berg, H.C. Adaptive Remodelling by FliN in the Bacterial Rotary Motor. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 3314–3324. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R.; Francis, N.R.; Xu, C.; DeRosier, D.J. The three-dimensional structure of the flagellar rotor from a clockwise-locked mutant of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 7039–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, H.S.; Dang, H.; Lai, Y.; De Rosier, D.J.; Khan, S. Variable Symmetry in Salmonella typhimurium Flagellar Motors. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluzel, P.; Surette, M.; Leibler, S. An Ultrasensitive Bacterial Motor Revealed by Monitoring Signaling Proteins in Single Cells. Science 2000, 287, 1652–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antani, J.D.; Shaji, A.; Gupta, R.; Lele, P.P. Reassessing the Standard Chemotaxis Framework for Understanding Biased Migration in Helicobacter pylori. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2024, 15, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.S.; Hazelbauer, G.L.; Falke, J.J. Signaling and sensory adaptation in Escherichia coli chemoreceptors: 2015 update. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnton, N.C.; Turner, L.; Rojevsky, S.; Berg, H.C. On torque and tumbling in swimming Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisevich, I.; Colin, R.; Yang, H.Y.; Ni, B.; Sourjik, V. Physics of swimming and its fitness cost determine strategies of bacterial investment in flagellar motility. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Carroll, B.L.; Liu, J. Structural basis of bacterial flagellar motor rotation and switching. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deme, J.C.; Johnson, S.; Vickery, O.; Aron, A.; Monkhouse, H.; Griffiths, T.; James, R.H.; Berks, B.C.; Coulton, J.W.; Stansfeld, P.J.; et al. Structures of the stator complex that drives rotation of the bacterial flagellum. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiveri, M.; Roa-Eguiara, A.; Kühne, C.; Wadhwa, N.; Hu, H.; Berg, H.C.; Erhardt, M.; Taylor, N.M. Structure and Function of Stator Units of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. Cell 2020, 183, 244–257.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Santiveri, M.; Wadhwa, N.; Berg, H.C.; Erhardt, M.; Taylor, N.M. Structural basis of torque generation in the bi-directional bacterial flagellar motor. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022, 47, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Carroll, B.L.; Zhao, X.; Charon, N.W.; Norris, S.J.; Motaleb, A.; Li, C.; Liu, J. Molecular mechanism for rotational switching of the bacterial flagellar motor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.L.; Nishikino, T.; Guo, W.; Zhu, S.; Kojima, S.; Homma, M.; Liu, J. The flagellar motor of Vibrio alginolyticus undergoes major structural remodeling during rotational switching. eLife 2020, 9, e61446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S.; Imada, K.; Sakuma, M.; Sudo, Y.; Kojima, C.; Minamino, T.; Homma, M.; Namba, K. Stator assembly and activation mechanism of the flagellar motor by the periplasmic region of MotB. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 73, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Miyata, T.; Terahara, N.; Mori, K.; Inoue, Y.; Morimoto, Y.V.; Kato, T.; Namba, K.; Minamino, T. Novel Insights into Conformational Rearrangements of the Bacterial Flagellar Switch Complex. mBio 2019, 10, e00079-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sharp, L.L.; Tang, H.L.; Lloyd, S.A.; Billings, S.; Braun, T.F.; Blair, D.F. Function of Protonatable Residues in the Flagellar Motor of Escherichia coli: A Critical Role for Asp 32 of MotB. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Dapice, M.; Reese, T.S. Effects of mot gene expression on the structure of the flagellar motor. J. Mol. Biol. 1988, 202, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.W.; Leake, M.C.; Chandler, J.H.; Lo, C.-J.; Armitage, J.P.; Berry, R.M. The maximum number of torque-generating units in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli is at least 11. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8066–8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Berg, H.C. Resurrection of the flagellar rotary motor near zero load. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1182–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Yuan, J.; Lele, P.P. Bacterial Proprioception: Can a Bacterium Sense Its Movement? Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 928408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, R.; Ford, K.M.; Lele, P.P. Torque, but not FliL, regulates mechanosensitive flagellar motor-function. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, N.; Phillips, R.; Berg, H.C. Torque-dependent remodeling of the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 11764–11769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nord, A.L.; Gachon, E.; Perez-Carrasco, R.; Nirody, J.A.; Barducci, A.; Berry, R.M.; Pedaci, F. Catch bond drives stator mechanosensitivity in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 12952–12957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antani, J.D.; Gupta, R.; Lee, A.H.; Rhee, K.Y.; Manson, M.D.; Lele, P.P. Mechanosensitive recruitment of stator units promotes binding of the response regulator CheY-P to the flagellar motor. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lin, T.; Botkin, D.J.; McCrum, E.; Winkler, H.; Norris, S.J. Intact Flagellar Motor of Borrelia burgdorferi Revealed by Cryo-Electron. Tomography: Evidence for Stator Ring Curvature and Rotor/C-Ring Assembly Flexion. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 5026–5036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beeby, M.; Ribardo, D.A.; Brennan, C.A.; Ruby, E.G.; Jensen, G.J.; Hendrixson, D.R. Diverse high-torque bacterial flagellar motors assemble wider stator rings using a conserved protein scaffold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1917–E1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachiyama, S.; Chan, K.L.; Liu, X.; Hathroubi, S.; Li, W.; Peterson, B.; Khan, M.F.; Ottemann, K.M.; Liu, J.; Roujeinikova, A. The flagellar motor protein FliL forms a scaffold of circumferentially positioned rings required for stator activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2118401119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Lin, W.-T.; Zhu, S.; Franco, A.T.; Liu, J. Imaging the motility and chemotaxis machineries in Helicobacter pylori by cryo-electron tomography. J. Bacteriol. 2017, 199, e00695-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leake, M.C.; Chandler, J.H.; Wadhams, G.H.; Bai, F.; Berry, R.M.; Armitage, J.P. Stoichiometry and turnover in single, functioning membrane protein complexes. Nature 2006, 443, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosking, E.R.; Vogt, C.; Bakker, E.P.; Manson, M.D. The Escherichia coli MotAB proton channel unplugged. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 364, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, Y.V.; Che, Y.-S.; Minamino, T.; Namba, K. Proton-conductivity assay of plugged and unplugged MotA/B proton channel by cytoplasmic pHluorin expressed in Salmonella. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 1268–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homma, M.; Kojima, S. The Periplasmic Domain of the Ion-Conducting Stator of Bacterial Flagella Regulates Force Generation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 869187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.I.; Nakamura, S.; Toyabe, S. Cooperative stator assembly of bacterial flagellar motor mediated by rotation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Minamino, T. Flagella-Driven Motility of Bacteria. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishihara, Y.; Kitao, A. Gate-controlled proton diffusion and protonation-induced ratchet motion in the stator of the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7737–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, D.F. Flagellar movement driven by proton translocation. FEBS Lett. 2003, 545, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieu, M.; Krutyholowa, R.; Taylor NM, I.; Berry, R.M. A new class of biological ion-driven rotary molecular motors with 5:2 symmetry. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 948383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, W.S.; Berry, R.M.; Berg, H.C. Torque-generating units of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli have a high duty ratio. Nature 2000, 403, 444–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, D.C.; Berg, H.C. Powering the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli with an external voltage source. Nature 1995, 375, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Namba, K. A proposed gear mechanism for torque generation in the flagellar motor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Liu, J. The Bacterial Flagellar Motor: Insights Into Torque Generation, Rotational Switching, and Mechanosensing. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 911114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Deme, J.C.; Furlong, E.J.; Caesar, J.J.E.; Chevance, F.F.V.; Hughes, K.T.; Lea, S.M. Structural basis of directional switching by the bacterial flagellum. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Han, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y. Structural basis of the bacterial flagellar motor rotational switching. Cell Res. 2024, 34, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramoto, K.; Macnab, R.M. Deletion analysis of MotA and MotB, components of the force-generating unit in the flagellar motor of Salmonella. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 29, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S. The helix rearrangement in the periplasmic domain of the flagellar stator B subunit activates peptidoglycan binding and ion Influx. Structure 2018, 26, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.S. Bacterial chemotaxis: A new player in response regulator dephosphorylation. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 1492–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanoiri, Y.; Hijikata, A.; Nishino, Y.; Gohara, M.; Onoue, Y.; Kojima, S.; Kojima, C.; Shirai, T.; Kainosho, M.; Homma, M. Structural and Functional Analysis of the C-Terminal Region of FliG, an Essential Motor Component of Vibrio Na+-Driven Flagella. Structure 2017, 25, 1540–1548.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.-H. Multiple conformations of the FliG C-terminal domain provide insight into flagellar motor switching. Structure 2012, 20, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Singh, P.K.; Sharma, P.; Afanzar, O.; Goldfarb, M.H.; Maklashina, E.; Eisenbach, M.; Cecchini, G.; Iverson, T.M. CryoEM structures reveal how the bacterial flagellum rotates and switches direction. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, F.; Branch, R.W.; Nicolau, D.V.; Pilizota, T.; Steel, B.C.; Maini, P.K.; Berry, R.M. Conformational Spread as a Mechanism for Cooperativity in the Bacterial Flagellar Switch. Science 2010, 327, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Shi, H.; He, R.; Wang, R.; Zhang, R.; Yuan, J. Non-equilibrium effect in the allosteric regulation of the bacterial flagellar switch. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xu, H.; Chang, Y.; Motaleb, M.A.; Liu, J. FliL ring enhances the function of periplasmic flagella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117245119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-S.; Zhu, S.; Kojima, S.; Homma, M.; Lo, C.-J. FliL association with flagellar stator in the sodium-driven Vibrio motor characterized by the fluorescent microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenal, U.; White, J.; Shapiro, L. Caulobacter flagellar function, but not assembly, requires FliL, a non-polarly localized membrane protein present in all cell types. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 243, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joshi, A.; Lele, P.P. Scrutinizing Stator Rotation in the Bacterial Flagellum: Reconciling Experiments and Switching Models. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15030355

Joshi A, Lele PP. Scrutinizing Stator Rotation in the Bacterial Flagellum: Reconciling Experiments and Switching Models. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(3):355. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15030355

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoshi, Ayush, and Pushkar P. Lele. 2025. "Scrutinizing Stator Rotation in the Bacterial Flagellum: Reconciling Experiments and Switching Models" Biomolecules 15, no. 3: 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15030355

APA StyleJoshi, A., & Lele, P. P. (2025). Scrutinizing Stator Rotation in the Bacterial Flagellum: Reconciling Experiments and Switching Models. Biomolecules, 15(3), 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15030355