1. Introduction

Space and place are two fundamental concepts in geography, and more broadly in the social sciences, the humanities, and information science. The word space comes from the Old French

espace, which evolved from the Latin word

spatium, of which the literal meaning was

that which is enlarged. The term place, on the other hand, comes from the Latin word

platea, meaning open space, but carries the same meaning as the Latin word

locus, which is the root of all modern English words related to location. As opposed to space, which is more abstract in terms of our human consciousness (think about, for instance, arbitrary state boarders that cut through geographical features like mountains and rivers), place and location are more tangible to humans. In the English language, it is safe to say that people typically think in terms of place as defined by Tuan in 1979 [

1], but it is not clear from the literature what the situation is in other languages and what the roles of language and culture are in the space-place nexus.

It is worth noting that the notion of place is intertwined with human experience [

2]. Considering the complex nature of human experience, places may exist in a variety of forms. Indicatively, real places are derived from spatial or physical experience, whereas fictional or imaginary places are based on mental, virtual, spiritual or emotional experience, for example, ‘heaven’. Tuan states that “place is space infused with human meaning” and argues for two main concepts—that humans are rooted in place and possess and cultivate a sense of place. For the purposes of this work, we consider place as a product of human thinking [

3] that is derived from spatial experience and used to describe a portion of cartesian space.

In a bid to understand the human meaning rooted in places, place-based analyses have rapidly gained popularity in Geographic Information Science (GIScience) in recent years. Although place-based investigations into human phenomena have been widely conducted in the humanities and social sciences over the last decades, this notion has only recently transgressed into GIScience, which can be considered as a multidisciplinary and multiparadigmatic field [

4]. The broad umbrella term for place-centred analyses in GIScience has been informally defined as place-based GIS, which comprises research branches from automated computational place modelling on one end of the spectrum, to theoretical discussions, as, for instance, in critical GIS, on the other end.

Central to the research branches concerned with place-based GIS is the notion of placing the individual at the focal point of the investigation to assess human-environment relationships—although such a focus shall not exclude research on a collective sense of place. This requires the formalisation of place, which poses a significant research challenge on several levels. The first challenge lies in finding an unambiguous definition of place, to subsequently be able to translate it into formalised binary code, which computers and GIS can handle. This computational formalisation poses the next challenge, due to the inherent vagueness and subjectivity of human data. The last challenge is in ensuring the transferability of results, which requires large samples of highly subjective data. Another important characteristic in place-based GIS is the development of place-based operations or analysis functionalities in analogy to their spatial counterparts. The challenge lies in transforming traditional GIS operations such as spatial buffers and joins [

5] or in developing completely new ones to deal with the hierarchical and other semantic structures of places. However, the construction of place-based GIS may vary between different cultural perspectives and individuals.

The definition of an object in space depends on objective references as well as on cultural and subjective references. While in philosophy the word object is used very widely and can refer to a thing, being or concept, we restrict our understanding of an object in space to a physical world entity or a group of entities that refer to a material thing that can be seen and touched. GIS objects are user-defined objects that refer to feature classes and can also include abstractions such as watersheds. Problems can occur between different languages when GIS users refer to objects—actually having in mind different concepts. Language is one of the fundamental expressions of cultural processes, and it can be organised in different schemes, which can be extended to the spatial view. The speaker linguistically depends on a cultural preselection of alternatives to define spatial conditions and processes [

6]. Language can structure the space through a “linguistical space,” which facilitates the interpretation of spatial relations between objects [

7]. These objects can also differ from each other. For instance, one object can be geometrically simpler, of greater relevance, and less immediately perceivable compared to the other object [

7]. To which extent the culturally-dependent differences of conceptions and linguistic interpretations of spatially-located objects affects the sense of place—and, in consequence, the development of place-based GIS—is an open question that will need the development of revisited epistemologies and transferable frameworks in GIScience. Our research aims to analyse how the linguistic differences may cause confusion among scholars.

We believe that it is important to address the potential divergence of the concept of place based on language and culture as a preceding step to a broad conceptual formalisation, especially in the age of ubiquitous spatial data. With the increasing availability of user-generated content, social media and geo-social network data, and human digital trajectories generated from GPS devices or smart phones, powerful new opportunities are emerging for researchers to study the semantics and computational representations of places, and individuals’ observations, experiences, and exposures to ambient environments, as well as associated human-place interactions [

8,

9]. Together with the increasing data availability, Geographic Information Systems (GIS, GISs for plural) themselves are also becoming ever more sophisticated, and have been remarkably successful in conquering the desktops of scientists, businesses and public administrations, where they are used to handle information on spatial entities such as streets, parcels, rivers, forest patches or airports, to name a few examples.

In the first years of GIS, the focus was clearly on the tangible environment. In the 1990s, the term “GIS” was widely understood as an approach to geographic inquiry and spatial data handling. In fact, Goodchild [

10] drove the mainstream academic view of GIS to a series of technologies for collecting, manipulating, and representing spatial information as well as a way of thinking about spatial data [

11]. Today, the situation is very different—at least technologically, and in terms of how information is stored and distributed. GIS are no pipestone systems anymore; GIS and geospatial analysis, in general, are rapidly changing. One of the triggers of these changes was the advent of virtual globes such as Google Earth [

12], which shifted the capabilities of GIS into the collective consciousness. Today, a wide range of technology is available to support location-based services and analyses, and the Internet provides the necessary underlying cyberinfrastructure. Still, these developments do not cause GIS to be understood by the masses. Overall, GIS answers spatial questions in its applications, whereas common people rarely think about geographical space or abstract concepts.

This sounds exciting and is a promising step towards an era of studying and amalgamating individual views of the world to better understand aspects of human-environment interaction. Still, one of the central defining characteristics of GIS is the production of spatial representations of those data. Does GIS as a product of computers allow for the individualisation of objects? GISs are on everybody’s desktop, or smartphone. Many of the underlying geometric operations have been established over the last forty years or so. Of course, real-time applications, augmented reality, or indoor navigation are more recent challenges. Still, one of the major challenges is to use spatial information in the same way humans do. This may include placenames and functions for places. We, therefore, may critically ask whether GISs are nowadays ready to accommodate place concepts, or, if this is not the case, at least not to a large extent, where the problem lies. Our hypothesis is that next to the well-known difficulties of accommodating subjective, personal, vague and perhaps contradicting information in GIS, language and cultural settings play a more important role than so far addressed in GIS and GIScience literature.

While the English language clearly differentiates between “space” and “place”, the situation is different in some other languages such as German, Greek, or Spanish (and many others). By considering only the English term

place to investigate the human experience in the physical environment, we risk imposing an ethnocentric, Anglocentric perspective on a universal concept that is constructed by the “social reality” of different cultures. In the words of Edward Sapir, “it is quite an illusion to imagine that one adjusts to reality essentially without the use of language and that language is merely an incidental means of solving specific problems of communication or reflection. The fact of the matter is that the ‘real world’ is to a large extent unconsciously built up on the language habits of the group. No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality. The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with different labels attached” [

13] (p. 162).

What Sapir and other proponents of this view, including Wilhelm von Humboldt, postulate, is that linguistic terms are concepts we inherit from our culture to make sense of the world. Other people in other societies inherit other concepts from their culture, and none of these concepts are inherently privileged or superior to the others. It is, therefore, perhaps inappropriate to investigate place as though it is the prevalent universal concept, rather than, for example, Lugar (Spanish) or Raum (German). In the remainder of this article, we will prototypically address how the place and space terms are handled by comparing selected languages, whereby language is inextricably intertwined with culture. It is therefore unclear whether international scientists who write about place in English language have the same underlying concepts in mind if they have been conditioned by different social realities. We need to critically ask if recent concepts to handle place in GIS adequately support the integration of the machine learning algorithms that facilitate data entry, capture, and reproduction from traditional and non-traditional sources such massive movement data, near-real-time information or social media information.

2. Humans Tend to Think in Terms of Place Whereas Computers Deal With Space

Without going into detail, it is safe to postulate that humans tend to think in terms of places, rather than spaces. This statement may sound trivial, with attempts of addressing this thinking in the digital world being few and far between until a few years ago. Through the incubation of Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) concepts within GIScience [

14,

15], we have recently witnessed significant progress in handling vague or subjective data. This development is strong in language processing. Literally hundreds, if not thousands, of articles analyse text, for instance from social media, often along with contextual analyses in space and time. Likewise, we witness the increase in innovative applications utilising artificial intelligence methods in machine learning (e.g., deep learning), or data mining to extract knowledge from big data. This emerging field is sometimes called artificial geospatial intelligence (geoAI, [

15,

16]).

The fact that humans tend to think in a place-based manner is related to our predominantly indirect cognition of the physical environment. As humans, we do not experience our environment as an assemblage, but through physiological stimuli caused by physical entities or processes. These stimuli are ultimately translated into crystallisations of feelings and emotions. Thus, humans think in terms of place because we developed the “sense of place”, which is based on our perception of the world and, at the same time, frames our behaviour [

17]. The sense of place is embedded in a—predominantly—objective structure, namely, space. However, the same space can have different senses of place, depending on which person is experiencing this space (see

Figure 1).

Since humans tend to take on a place perspective, most digital representation systems face a conceptual problem because the majority of digital presentations are built on crisp entities and hardly account for the vagueness and spatial uncertainty in the actual areas that exert contextual influences on humans or their footprints being studied. Thus, analysis results are sensitive to different delineations of spatial or contextual units—also including the temporal dimension of spatial objects, which is, for the sake of simplicity, not heavily touched upon in this article.

These spatial or contextual delineations influence the way we interpret a diversity of phenomena, and this issue may have important implications for decision-making. For instance, health inequalities in a study area reported in two different spatial units (different scale and different shape) may offer divergent information to policymakers, influencing decisions that affect people´s quality of life. The delineations spatially define the context or environment where people experience liveability. Social scientists consider the conditions of individuals living in specific liveable or healthy environments in the context of specific levels of neighbourhood-based characteristics, such as social cohesion, green areas or neighbourhood health-related issues. This may go along with the notion of services—such as the ecosystem service approach—and a certain capacity of accessibility to services such as health services [

18] or recreational services [

19]. Public health studies so far predominantly used residential neighbourhoods in the form of static administrative areas, such as census tracts or postcode units. Over the last years, more and more studies have demonstrated ways to overcome fixed boundaries in this field of research.

Kwan [

20] pointed out that residential neighbourhoods might not accurately represent the actual areas that exert contextual influences on the health outcome being studied. This has been confirmed by recent studies. For instance, Wei et al. [

21] applied clustering methods to generate neighbourhood areas that are “meaningful” representations of place in relation to people’s perceptions. Additionally, Kwan [

22] also stated that contextual effects are idiosyncratic; in other words, people´s responses to local effects are very personal and vary depending on each individual’s way of thinking. This idiosyncratic-dependent interpretation of the world challenges the formal and traditional spatial representations because the available geoinformation systems are not able to simultaneously represent the diversity of perceptions, interpretations and ideologies of people, and are confined to representing information in the spatial realm.

However, so far, problems mentioned in the literature mainly addressed the fact that it is often difficult to clearly delineate boundaries or that some boundaries might not be congruent with a given geographic spatial unit. Less so, it has been argued that GIS should be able to represent and analyse fuzzy or vague spatial information to better serve a human-centred view. In the next section, we will articulate the challenges for GIS in handling space. As a starting point, we may refer to Entrikin [

23], who further developed the general place concept as formulated by Tuan [

1] and others. Entrikin [

23] refers to specific places as a fusion of space and experience that gives areas of the Earth’s surface a “wholeness” or an “individuality.”

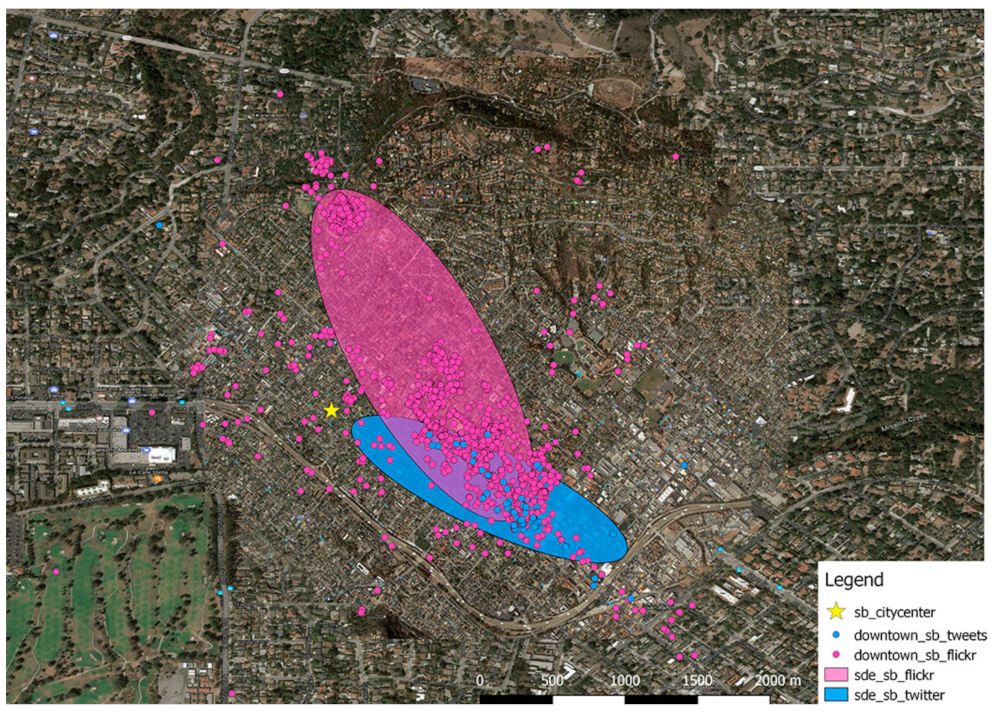

Agnew [

24] suggested that the definition of place includes three aspects: (1) location—where an activity or object is located; (2) locale—the environment where every day human activities take place; and (3) sense of place—the experiences offered by a place or a community to a group of people and their shared perceptions and conceptualisation of a place. Still, the authors perceive that even the first step of this methodology is ambiguous in practice (see

Figure 2). One obvious solution for step 1 in Agnew’s framework is to primarily focus on individual spatial objects—instead of a direct valuation of a place. Psychometric approaches can then measure sense-of-place variables; typically, the strength of association between individuals and some researcher-defined spatial object [

25]. Environmental psychology also has a tradition of mapping spatial settings and developing methods in natural resource management for measuring the spatial component of the sense of place—but there are surprisingly little exchange and co-citations between the fields of geography and environmental psychology. Jorgensen et al. [

25] integrate spatial methods with an attitudinal approach that captures individual-level spatial variation and its meaning based on structural equation modelling to integrate the spatial and physical features of places with attitude and behavioural variables. Jack [

26] investigates the significance of children’s place attachments for the development of their identity, security and sense of belonging. Golledge and co-workers [

27,

28,

29] worked for many years to bridge the two disciplines but with limited success—beyond their own scholarly work. Although a “spatial turn” has been diagnosed for other social sciences like sociology and the humanities [

30], places are predominantly seen as the sites of social relations [

24] by acting as open articulations of connections [

31]. In this sense, a place is constructed by inter—connected people with place-specific social forms expressed in the space [

32]. To this end, we may temporarily summarise that people think in terms of places, and place is the underlying entity in which human interaction takes place.

4. Place: A Language Perspective

Humans not only tend to think in place terms but they also refer to objects. Objects may help people to organise their personal representation of a world. Objects particularly help humans make sense of their surroundings in a complex world and their quest to decompose complexity [

76]. Technically, geospatial objects may be interpreted as a rigid conceptualisation in space and time. Their meaning is ambiguous between culture and languages as well know examples like forest, mountain, pond or village show. When verbally addressing geo-objects, humans often use language-, culture- and context-specific notions instead of sticking to terms that are generically understood across countries and societies. Therefore, when dealing with place and geospatial objects in context, it is necessary to consider languages and perhaps specific cultural settings. First and foremost, we need to consider the English language, which has evolved as the

lingua Franca of science over the last decades, and then adding perspectives from several other languages—and cultures.

In this research, we aimed to determine how the term and concept of place translate into select few other languages, both linguistically and culturally. Although many perceive translation to be a mere transfer of words and sentences between languages, it actually far transcends the linguistic scope and acts as a communication interface between cultures. As different languages are deeply nested within different cultures, the act of translation involves comparing cultures and using that intercultural knowledge to generate an adequate and equivalent linguistic translation. While “adequacy” refers to the translation fulfilling the intended communicative purpose of the source text, equivalence describes a relationship of equal meaning and stylistic connotations in the target text. Both notions are paramount when accounting for systemic differences between the source and target languages, as different languages often have no direct counterpart for certain words or concepts in function and/or form. For example, there is no satisfactory functional English equivalent for the culture-specific Italian phrase Buon appetito (I wish you a good appetite)—or at least regarding its actual use in day-to-day utterance, whereas other cross-cultural practices may be similar in function but different in form. For instance, the naming of kinship relationships may fulfil the same function across different languages and cultures (to construct personal and social identities and family ties) but take on a different form. In English, for example, the word grandmother can mean the mother of one’s mother or the mother of one’s father, whereas these two concepts are expressed by two separate words in Thai. These examples illustrate how language and culture are intertwined, and how adequate and equivalent translations must consider both the function and form of certain words in certain contexts.

4.1. English

In English, there is a distinct difference between the words and the associated concepts of place and space. Both words have several different meanings, which is not uncommon in the English language. For example, “space” refers to the infinite expanse beyond our Earth’s atmosphere; it refers to the notion of availability, as in space being available on a bus or in an educational programme; and, perhaps most importantly for us as GIScientists, it refers to the dimensions of height, depth, and width within which things exist and move (Cartesian space). For practical reasons related to culture and administration, the Earth’s space as a whole was subdivided into the spatial administrative units of countries and sub-units of states/territories and cities/towns a long time ago, and many such boundaries have evolved and shifted together with power relations throughout history—this is an ongoing process which can happen relatively quickly and unexpectedly like when countries like Yugoslavia or the Soviet Union dissipated. Still, in most cases, citizens of a country, a province or a city feel a personal and cultural association with that particular

place, and it is such a personal connection that transforms “space” into “place”. While the term place is yet to be unanimously defined, GIScience scholars agree that it essentially refers to space contextualised by human emotion or action, i.e., “space invested with meaning in the context of power” [

77] (p. 12); the “conceptual fusion of space and experience” [

23] (p. 6); or “meaningful segments of space” [

78] (p. 3). However, the term place also functions in a variety of other contexts, for example, a designated portion of space, “the picture has its place on the shelf”; a position in a sequence or series, “she came in at first place”; and as a verb “they place great emphasis on doing it right”. This conceptual and linguistic ambiguity surrounding both place and space is perhaps what makes the concepts so hard to define, delineate, and differentiate.

4.2. Spanish

In the Spanish language, the word “space” translates to

espacio, and the word “place” to

lugar. However, the word

lugar is often used when referring to “location”, but it is also a concept linked to activities in a space (e.g.,

¿En qué lugar nos reunimos para estudiar?—Which place we are going to meet to study in?) and the sense of belonging to a context and situation (e.g.,

Encontré mi lugar en el mundo—I found my place in the world). In the Spanish language,

lugar is also associated to

la construcción social del espacio [

79], the social construction of the space. In this sense, the concept of place in the Spanish language might be approached through Lefebvre´s concept [

80] of the production of social space. For Lefebvre, the social space becomes a metaphor of social life, linking the concept of space to the subjective experiences of human beings. Place,

lugar, in the Spanish language can be defined as the social construction of space. In other words, the space by means of place can be conceived in terms of the “spatial experience”, the meaning that the individuals give to the space, consequentially, the social construction of the space not only refers to the objective space, but especially the sense individuals give to this space: the sense of place [

81]. Thus, the space can also be conceived as a social space, the space where diverse social relations processes are integrated and can be interpreted as spatial practices, which include what can be called “specific places”—

lugares concretos [

82].

In this perspective, in the Spanish language, the space vs place issue is not so much a matter of opposition, but rather one of integration and assimilation. Therefore, space can be understood by the relation of people with their environment, the “spatial” experience of people, understanding the space as a socioeconomic and sociocultural product where people develop their life [

79]. This space-place view of life is associated with the term

espacios de vida, the spaces of life.

Espacios de vida refers to the daily life experiences of people, as well as to the narratives that are created and articulated from these experiences [

79,

81]. In Spanish language thinking, there is a recognition of the space as the base of the production of social life, and there is also a valorisation of the simplicity of the individual and collective daily life as key issues to understand spatiality. For Spanish native speakers, another important term to understand regarding the space and place concepts is

territorio (territory).

Territorio refers to a conceptual category that reflects power relations and is interpreted as a political dimension that can be expressed in space [

82].

Territorio can also be considered as a concrete category of space and links society and nature under a perspective of social and cultural appropriation, transformation and use of this nature [

83]. Thus,

territorio is the expression of space-place interactions.

Territorio includes the physical container of the social, a container that shapes the social, economic and cultural dynamics, and these dynamics are also shaping this physical container. Space is produced through the sense of place, and the sense of place also reacts to the spatiality. Different

territorios might be created in confronted spaces. For instance, for people living in a neighbourhood,

el territorio del barrio (the neighbourhood´s territory) might be associated with a space that disagrees with the neighbourhood delineations designed by local authorities. Therefore,

territorio can also be defined as a place-based concept defined by political and social interests. The relevance of the term

territorio in the Spanish language can be also seen on the term

ordenamiento territorial. The English language equivalents for

ordenamiento territorial are land-use planning, spatial planning, or land-use zoning. We see here another example of the “amalgamation” of space and place concepts in the Spanish language.

Territorio and

ordenamiento territorial integrates notions of space and place,

territorio can be a place that is contained in space, and

ordenamiento territorial is the social planning of the space, based on the physical and human characteristics of this space. In the Latin-American perspective, the term

territorio is more marked by the sense of place. In contrast with the European view of

territorio as a category that reflects power relations (e.g., the land that belongs to the jurisdiction of a state), Latin-American thinking stressed the cultural and symbolic dimensions of

territorio and emphasises the importance of the concept for the rural world and environmental movements [

83]. The cultural and symbolic dimensions define the identity of the

lugar, of the place.

Lugar is a space that is markedly symbolised [

75,

84]. For this reason,

territorio has also become a key term used by indigenous communities in Latin-America. For the indigenous world,

territorio is not only the space they live in, but also the space charged by ancestral symbolic meaning. Indigenous identity is linked to their

territorio ancestral (ancestral territory).

4.3. German

GIScience scholars with a German speaking background may have a hard time to fully embrace the place vs space debate in scientific (English) language literature. The German language mainly uses one term for almost all aspects of space and place:

Raum. A typical translation of this word as “space” is problematic. Likewise,

place is an English word with very different connotations from the German

Raum [

85].

Raum may refer to the common English notion of space as a boundless three-dimensional extent in which objects and events occur and have relative position and direction. This notion of space, as represented by the grid of the map, was foundational to the Renaissance artistic construction of perspective and landscape painting. In another sense, however,

Raum also refers to the sort of enclosed room-like area that is demarcated, for example, by the territories of historically constituted places [

85].

Raum is therefore associated with the term

Landschaft and is, therefore, concerned with space as well as with the place [

85].

It is not our intent to discuss the ontological and epistemological aspects of

Landschaft. We may only need to address some consequences of the German roots of the discipline of Geography, which may be traced back to Hettner [

86]. According to Harvey & Wardenga [

87] this has even influenced American Geography, which has been guided by the scholarly work of Hartshorne [

88] through Hartshorne’s “selective adaptation of Hettner’s work, his selective engagement with German critiques of Hettner’s ideas, and the consequences of his relative neglect of regionalist and organic concepts of geography in inter-war Germany” [

87].

For Hettner, geographic facts did not exist

per se but were only the results of chronological observations. “Consequently, a ‘geographic’ observation was a fact only when and as far as it showed differences between places (

örtliche Verschiedenheit); and only when and as far as these differences between places stood as causes or results in primary relationship to collections of facts with other differences between places. As far as geographic facts were constructions, this approach was applicable to regions (

Räume), the fundamental epistemological object of

Länderkunde and geography for Hettner. Consequently, regions were not ideals to be “found” in reality but were “produced” through a methodologically systematic process of regionalization” [

87].

In Geography, scholars have often tried to overcome the dominance of the single term Raum. Ort is the German word that comes closest to the term place, but it is hardly used in conjunction with GIS, which already illustrates a part of the problem: in the German-speaking countries, Geography played a minor role in the development of GIS. At universities, particularly in Germany, surveying and geodesy provided much input at the technical level but less so at a methodological or epistemological level. This led to the fact that the English term Geographic Information System was often translated to Geo-Informationssystem (about two times more often according to Google Scholar), simply to avoid the name of Geography as a discipline as part of the term. Due to the weak role of Geography in the development of GIS methods and methodologies in the German speaking countries, concepts of human geography are today widely absent in the GIS literature in German language, and the term GIScience has a weak base in terms of scientific programmes, institutions, classes, textbooks or scholarly articles.

To summarise, widely used concepts like spatial formation, spatial systems, or spatial problems would not seem to be particularly problematic to be adopted to place-based GIS due to the high degree of ambiguity for German language speakers when associating Raum concepts with GIS. In almost complete contrast, University programmes in German-speaking countries have a hard time teaching students to unmistakeably distinguish between space and place in the English language.

4.4. Greek

Ancient Greek philosophy played an important role in sculpting the foundation of Modern Greek mentality. Great figures of the past, such as Aristotle, Democritus, Plato and so forth attempted to observe, define and describe subjects of interest, creating concepts that influence, among others, Greek vernacular even today. The terms of place and space have a common point of reference, that is, an entity with spatial properties; despite their interrelated nature, these terms infer two distinct concepts. According to dictionary entries [

89], the Greek equivalent of space is

χώρος (chóros) and is defined as “1. a geographical (or not) extent, 2. a plane with particular dimensions or 3. an empty area that physical entities can occupy”. This definition conforms to the concept of space as it is introduced by Aristotle and Plato; that is, a geometrical notion disconnected from matter and time [

90]. Consequently, the idiomatic use of space enables referrers to talk about motion, change of status or existence of entities within a geometrically defined spatial extent.

Algra [

91] further investigates the modern use of the term space in the Greek language, arguing that it refers to “an underlying frame or references and a sum total of places”. This yields three possible evaluations; space is (a) a reservoir of physical possibilities (b) a framework of locations, and (c) a container, in which things can exist or not and move. The first is interpreted as the extension of individual physical things; it is equivalent to the phrase “-occupies” and describes the geometrical space in which something is present. Indicative knop in this context includes “the space occupied by the volume of a person” or “the empty space where a box can fit in”. Similarly, the phrases “use this space”, “this is my space” or “I need my personal space” refer to the geometrical extent that a person defines as his/her own psychological barrier, within which a status is achieved, such as security, privacy or property.

The second interpretation refers to expressions of the location and order of things in terms of their surroundings. Notable examples in vernacular include: “the fish is swimming in the water”, “let A(x, y) be a point in the Euclidean space”, and “the balloon is stuck at the corner of the ceiling”. Although the spatial reference is achieved through physical entities, each of the aforementioned referents refers to the collection of locations that form the geometrical space of the water body, two-dimensional Euclidean plane and ceiling, respectively. Finally, the third interpretation extends the former to include the notion of relative space and the ability of things to move in it. Some notable examples are: “the aircraft is entering the Greek airspace”, “Bob is (located in the space) where Alice was”, “Voyager 1 exits the heliosphere” and so on.

On the other side of the spectrum, place is translated as τόπος (tόpos) and is defined as “1. a spatial extent with a specific property that is not strictly determined or confined, 2. a specific geographic region or area (usually determined by a name or a property), 3. the spatial extent that a physical entity occupies, 4. the environment in the sense of its surroundings or 5. a collection of locations or points in space that share the same properties” [

89].

Based on the aforementioned definition, place cannot stand alone, as opposed to space; instead, it is always expressed in combination with properties or other external entities. Algra [

91] states that place has a relational setting in the Greek language and is usually referred as “the place of something”. Similar to space, he defines three possible evaluations: (a) material extension of a physical body; (b) relative location of a physical body; (c) part of the extension occupied by a physical body. The first interpretation resembles the first property of space, that is, the spatial extent that a physical body occupies in space. This is the only instance where place and space converge in Greek vernacular; however, a notable difference is that a spatial extent referred to as place tends to be vague and qualitatively approximated, as opposed to space. For instance, talking about a box placed in a room, a phrase like “the space that the box occupies covers one-third of the room” is valid. However, such precision is not usual in the context of place. Furthermore, the spatial extent expressed as place mainly emphasises an activity or property; for example, the following phrases are valid in Greek: “there is no available place for the box” and “the box occupies the whole place”. Note that both of the aforementioned examples mainly emphasise the inability to fit the box in the room by implying its spatial extent.

The second interpretation describes the location of a physical object based on the relative location of its surroundings. For instance, “Bob is in the kitchen”, “I am at the top of the mountain”, “the house is in a dried land”, “the place of birth is Athens”, and so forth. Finally, the last interpretation enhances the concept of space with the semantics of place. For instance, the sentence “the fish swim in the lake” implies that the fish exist in the geometrical space of the lake. However, the place name of lake infuses space with additional semantics, such as name, type, flora, fauna, location, surroundings, and so on.

In summary, space in the Greek language is considered as the absolute reference base, a container that will exist even if the objects are removed, whereas place refers to the description of the spatial experience.

4.5. Chinese

In Chinese, the word “space” usually refers to “空间 (kōng jiān)” while “place” often refers to “场所 (chǎng suǒ)” or “地方 (dì fāng)”. Space is more abstract and generic while the notion of place is more tangible to humans. The use of the concept of “space” in Chinese is almost identical to its use in English literature. However, the concept of “place” is a little bit different in varying contexts. “场所 (chǎng suǒ)” can afford different types of human activities in certain places, which are formed by the interaction of human and the environment. A physical space becomes a place only if it has been endowed with human intentionality, social life, cultural aspects, or other semantics. Places could be organised in a hierarchical way, and different spatial relationships exist among places [

70,

92]. “地方 (dì fāng)” has several meanings. First, it could refer to a location or a region, e.g., “在那个地方 (In that place)”. Second, it means “local”, which can be used as a comparison to “central”, e.g., “地方政府 (local government)”. Moreover, it could also be used as a venue, e.g., “找一个落脚的地方 (find a place to stay)”.

4.6. Hungarian

The Hungarian language is unique regarding its origin, and therefore it also differs from English (or almost any other) language in its vocabulary and grammar [

93]. However, the two main concepts of space and place are used in a similar fashion as in English.

Space is called

tér, and it often refers to rather objective and tangible areas, whereas spatial means

térbeli, which is mostly used for things and phenomena with three-dimensional extent. Interestingly,

tér also means square (as a public space, such as Trafalgar Square) in Hungarian. Regarding geographical interpretations,

tér is again used similarly to the English terminology, such as in the case of philosophical space concepts from Newton, Leibniz or Descartes [

94].

Place means

hely, and just as in English, it has much more subjective and intangible characteristics, often related to personal experience or impressions. Hamvas [

95] referred to this as the “

hely szelleme” (genius loci) or the atmosphere of a place. Another definition for

hely is the space (

tér) occupied by someone or something. It can be a real place, so, for example, the place for my shoes, where I often put them when I enter the house, but it can also be something metaphorical, e.g., I cannot find my place in society. The Hungarian word for location is also derived from the word

hely; it is called

helyzet. However, similar to

hely itself, it can refer to both, objective (such as geographical location) or metaphorical phenomena (social or life situation), as well.

A typical characteristic of the Hungarian language is that we add affixes to the stem of the word and, thereby, the meaning of the original root is changed. This also happens quite often with the words tér or hely, resulting in sometimes slightly or even completely different meanings than the original word. Terület would be one of the many examples, originating from the word tér (space), and it means either area, as the size or extent of a given unit (e.g., a country), or it can also mean territory as well. A similar example for the word hely as a stem is helyi, which means local or helyiség used as “premises”.

In general, we can say that, similar to English, the Hungarian interpretation and use of the words of place and space are slightly different in everyday language or as geographical concepts.

5. Discussion

From the point of view of Habermas [

96], language is the main mean of human interaction that shapes social networks and power relations. In this sense, language can be considered as one of the means to communicate meaningful places. The everyday life communication between individuals through the grammar of ordinary language can create common senses of place, community-based place attachments, and inclusive public spaces. Space and time are connected but, in terms of language, each one can be expressed independently. European languages tend to spatialise notions of feelings and time; for instance, time is “long” or “short” [

1,

97]. Moreover, humans are open to being informed by narratives [

1]. These narratives are highly influenced by culture. Culture serves as the background from which we generate specific places. In this context, the analysed languages in this paper have similarities and differences depending on the cultural and historical background of the Nations speaking these languages. In general, all languages have a notion that space acts more like a “container”, while place is more associated with human perceptions and experiences. Perhaps in the case of the German language, these differences blur in the word

Raum, because this word denotes an idea of extension (spatial) and also a space where life thrives (place). In this case, we find a similarity with the Spanish word

espacios de vida, which depicts interactions between space and place. In the Spanish language, the concept of

territorio also refers to the confluence of space and place, where not only biological life exists, but also social issues, power relations, and community life develop. In the English language, one of the main uses for the word space is to refer to the infinite expanse beyond our Earth’s atmosphere. An interesting difference compared to the other discussed languages is the Greek word

χώρος (chóros), which acts as an idiomatic base to describe an area that can be associated by concepts of motion, change and existence, and can also be interpreted as the sum of places. In Chinese language, we highlight the hierarchical spatial relationships between places, where 地方 (dì fāng) means “local”, but also can refer to a region. In the Hungarian language, a distinctive difference from the other languages is the word

tér that means square, and also space. A public square, a

tér, can be conceived as a place, a

hely, if it is an inclusive, healthy space that incentivises human communication and social cohesion.

While we emphasise the importance of the language in place-based GIS, we need to simultaneously emphasise the limitations of a purely language-centred view. First and foremost, spatial analysis is built on the universality of Tobler’s First Law of Geography, which states that "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things". When dealing with

space, it is central to the presentation and analysis of geographic information. Furthermore, an almost solely social construction of place as suggested by Habermas would not allow for a holistic or partial place definition through relations among relevant entities based on functions, as suggested by Papadakis et al. [

56,

98]. In essence, a particular place can be modelled based on spatial and non-spatial functions of entities, whose properties depend on the configuration of the relevant relations, modelled as functions (see also [

99]). Still, place is used inconsistent in the literature, both within GIScience and in other fields. Merschdorf and Blaschke review a broad range of GIScience literature and identify several research branches concerned with the formalisation and operationalisation of place. The identified branches comprise critical GIS, qualitative GIS, PPGIS/PGIS, affordances research, accessibility studies, VGI/crowdsourcing, semantics and ontologies, and place names/place modelling research. Merschdorf and Blaschke [

100] conclude that this needs to be founded on sound concepts and methodologies, based on a uniformly and unambiguously defined concept of place.

As Couclelis points out, there are great challenges for GIS. Rooted in absolute space, GIS does not represent relations well. This 1999 challenge seems to be almost solved based on technical developments. Still, conceptually, Couclelis points out that absolute space as geocoded locations are bound to a priori existing relations of geometry and topology among the corresponding points in the space, whereas in relative space the definition of a set of arbitrary relations comes first and the geometry and topology follow. We believe that many of the more recent research articles cited demonstrate a lot of progress that alleviates this condition, allowing relations defined by communication or movement over digital networks to be integrated. Jones [

101] positions relational space within philosophical approaches to space, drawing on examples taken mainly from human geography. He highlights some limitations, namely factors that constrain, structure and connect space and concludes that relationality is important but insists on the connected, sometimes inertial, and always context-specific nature of spatiality.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Place-Based GIS

The call for papers of the special issue “Place-based GIS” in

ISPRS International Journal of Geoinformation yielded a variety of interesting applied papers but less progress in the theoretical foundation. Our contribution aims to raise awareness about the important future role of place in Geoinformatics and Geographic Information Science and summarises recent developments. We could have started with fundamental philosophy such as the work of Kant who may have had an influence on the discipline of Geography, although in his later works Kant expressed an absolute view of space. Today, Geoinformatics, GIScience and to a large extent, Geography involve a relative view of space [

46,

99,

102,

103]. Indeed, much of the recent work—also the work cited in this article—addresses spatial-temporal processes. For simplicity, we use relative and relational space synonymously, but we need to emphasise that a fully operational GIS needs to decouple the place-space relations. While many of the existing prototypical or partial approaches to place-based GIS may be regarded as interim solutions, a fully functional place-based GIS should be not linked by space, at least not as a pre-requisite. The challenges lie in the formalisation of place, constructing novel computational data models, and transforming traditional space-oriented GIS analysis operations, or developing completely new ones in place-based GIS, in order to deal with the diverse semantics of place and platial relations with cultural and language differences.

This article revealed that the words place and space partly have different functions and/or forms across the different languages we analysed (

Table 1). These differences stem from the distinctive development of the culture that is projected within each language. However, there are also some essential similarities, likely products of culture influence. For instance, the mathematical view of space originates from the advancement of ancient Greek geometry, whereas the symbolic aspect of place is associated with the Latin etymology of

locus as location.

The word space mainly refers to an open area, where objects exist, phenomena manifest, and their potential behaviour is observed and analysed. Properties derived from mathematics and physics along with further semantics attribute space to features such as coordinates, area, volume, perimeter, distance, density, identity, name, characteristics and so on. One could conclude that the word space, despite the language used, reflects the physical and socioeconomic dimension of space [

104]. In other words, it is regarded as a semantically enriched physical space.

On the contrary, the word place differs depending on the language used. Indicatively, it may refer to an area described by interrelated objects, mereological associations or even relations that hold with an entity of interest. Although its underlying structure is context dependent and highly complicated to be generalised, there are some notable commonalities. Place, as it is used in everyday life, is not a standalone entity. It exists with respect to other entities that trigger an individual’s interest to talk about, and it is built on the relations that semantically or spatial associate the containing entities. With respect to the dimensions of space, the word place reflects the behavioural and symbolic space; it is a concept structured as a relational space composed of entities, whose identities, properties and relations are culturally dependent.

The basis of a place-based GIS could be introduced by examining the points of convergence and divergence of the term place in different languages. In fact, a functional place-based GIS requires graph-like structures that could represent relative space, leaving the traditional representation standards of point, line and polygon as complementary information. On the other hand, the representation of entities that comprise the relative space must be adjustable and go beyond spatial objects. In fact, it should facilitate the digitization of entities that depend on context and culture, such as individual persons, symbols, phenomena, and more. Furthermore, the functionality of a place-based GIS needs to accommodate idiosyncratic applications through a container of generalised functions, which is almost a contradiction in itself. An idiosyncratic view is typical of the humanities, which aim to understand the meaning of contingent, unique, and often cultural or subjective phenomena. Therefore, a place-based GIS may be important for the digital humanities and may allow the cultivation of regional specialities. It should still serve the scientific quest for a general theory, and, ultimately, the quest for human understanding. A place-based GIS may address problems that are near the cores of social sciences and the humanities.

6.2. The Role of Language and Culture for a Place-Based GIS

There seems to be a need for more theory, not necessarily a new theory but sometimes revisiting classic literature in Geography and other spatial sciences because both absolute and relative space involves scale issues. Future systems should aim to make sure that different analysis methods produce research results that are not per se different simply because of the different approach and different scales. This endeavour is complicated by language and cultural aspects when going beyond physically defined spatial entities and processes. We may summarise and highlight the following three aspects of culture as being most relevant to place-based GIS:

Different cultures have different value systems and different world views—this goes beyond approximating culture to language.

Therefore, culture provides the context for the experience of place.

Culture is the way of life; language is the means of expression.

GIS has not been known for handling the cultural aspects of place. This may be one of the remaining challenges, assuming that most general principles of handling spatial information are largely developed. Following the language discussion, the authors need to emphasise a statement of Jordan et al. [

105], who point out that places help to inform our own sense of personal identity, such as national, regional, cultural identity, socioeconomic identity, or religious identity. These authors refer to Entrikin [

23] and conclude that places make us identifiable to others—like in a case when people’s behaviour can be linked to the places they come from. We may, therefore, ask why all the developments mentioned in this article and many others have not led to implementations of place concepts in GIS—at least not beyond some prototypical examples at universities. There are several potential reasons, including technical challenges, ambiguities between different versions, e.g., an English and a Spanish version of the same software, etc., but an obvious—still speculative—explanation could be that it is not commercially relevant, although some studies indicate future applications such as “cognitively-aware” personalised city maps [

106]. Future research needs to systematically investigate these limitations and the most recent technical developments regarding their potential to contribute to a place-based GIS that accounts for language, culture, personal, and perhaps emotional settings.

We may, therefore, reconfirm statements from the introduction section, while building on the scholarly work of Entrikin [

23]. In an attempt to simplify this difficult issue, we may summarise that place has a specific meaning to different individuals and groups of individuals. Therefore, a specific place refers to the conceptual fusion of space and experience that gives areas of the Earth’s surface an “individuality”. This statement from Entrikin may need to be differentiated from generic types of places which do not necessarily refer to one particular part of the Earth’s surface—like “shopping area” or “downtown”. The latter variant of place also incorporates existential qualities of our experiences of place—but in a more abstract way and not necessarily including real personal experiences bound to a specific place—manifested in space. Goodchild [

70] (p. 97) pleads for more technical and theoretical work on place, to implement a vision of a “platial” technology that would in many ways complement geographic information systems”. An increasing number of researchers deal with this challenge. Some progress has been made, but we seem to be far away from operational solutions accounting for the sense of place, particularly if we want to handle place in GIS as cyberspace, the space of digital connections that continues to expand its hold on every aspect of society.

To summarise, we emphasise that a multi-cultural perspective is not simply a transfer of words between languages, but an entire value system, shaped by historical, political, and social context, that rarely matches in different cultures and that this cultural divergence (not so much the language) is what adds difficulty to the formalisation of place.

6.3. Place—A Central Concept for Digital Humanities

These developments open opportunities for the “digital humanities”. So far, humanity scholars have rarely worked with GIS, constructed to answer spatial questions, and most humanities have rarely employed geographical concepts in their analyses. With some of the developments sketched out in this article we can expect “spatial humanities” [

107] to be realised. After various “spatial turns”, we may witness the humanities taking their own digital turn, where mapping-based projects shift into focus. We increasingly see examples of merging narratives and numbers, supported by the development of new visualisation methods allowing for the fuzzy, ambiguous and spatially overlapping nature of place like “spraycans” [

108], overlapping isolines or diagrams [

109], or spatial video [

110]—although places can sometimes have clear or crisp boundaries, too. Developing place-based GIS techniques to help social scientists understand the relationships between large networks of entities could help a wide variety of social scientists, including sociologists who seek to understand human social networks, librarians and others who use bibliometrics for co-citation analysis of document databases, and linguists working on automating natural language parsing and translation. Ideally, we may yield insights and offer novel ways of interpreting a story and ultimately answering the “Why” questions. Ultimately, we may recognise that GIS have opened new and powerful means of spatial analysis but are increasingly viewed as media for communication—which necessitates the incorporation of cultural and language differences and to widen the perspective while being more inclusive. In other words, a “GIS as media” view calls for the integration of place-based GIS functionality.