1. Introduction

Historical censuses, first carried out in the British Isles in 1801, preserve snapshots of population size and characteristics. They are highly valued sources of information to understand the population and social structure in the past and their transition over time and are today crucial in historical GIS and digital spatial humanities. Many efforts in different countries have been made to digitise historical census records, which were initiated by genealogical researchers, organisations, and companies (e.g. FamilySearch (

https://www.familysearch.org) and Findmypast (

https://www.findmypast.co.uk)) in the past decades. For instance, the Censuses for Britain 1851–1911 [

1], the United States enumerations 1850–1940 [

2], and the 1911–1951 Canadian censuses [

3]. These digital copies of historical censuses have opened up new opportunities for historians, historical geographers, and other social scientists to investigate migration, health, economic activity, and social mobility in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Historical census records often contain explicit spatial attributes, such as enumeration unit names (e.g., registration district, parish, etc.), home addresses, or birthplace names, which cannot be directly imported into GIS. In order to incorporate map visualisation and spatial analytics into socio-economic studies (see Longley and Singleton [

9] and Singleton and Longley [

10]), geo-referencing techniques are required to transform textual descriptions of locations and places into geographical coordinates. There exists a variety of modern geo-referencing Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) supplied by map data and service providers, for example, Google Maps (

maps.google.com) and Open Street Map (

www.openstreetmap.org). Each works very effectively with current postal addresses, which are in standardised and hierarchical formats. However, historical census addresses are structured much less clearly. Particularly in rural areas, household addresses can simply be place names or building names such as “acre farm”, “butcher’s shop” or “clock inn”, which bear neither house numbers nor thoroughfare names. In addition, some common street names across the country, for instance, “Church Street”, “High Street”, or “Station Street”, create additional ambiguity for the geo-referencing process. Such uncertain and complex scenarios have posed significant challenges to geocoding historical census records and have impeded the spatial analysis of census data.

It is, therefore, a non-trivial task to geocode micro level census data before we can use them to investigate geo-demographics and internal migration of the late Victorian population. The main aim of this paper is to develop an automatic method of geo-referencing the household addresses from the 1901 Census in England and Wales. We demonstrate a fuzzy address matching method using two complementary address corpora and visualise the geocoded addresses in a series of maps. The results indicate that it is feasible to standardise and geocode a large share of unique addresses from the historical censuses at a national scale.

2. Related Work on Geo-referencing Historical Data

There are several significant contributions to geo-referencing practices in historical GIS [

11,

12,

13] projects, which broadly fall into two methodological paradigms. The first strategy is to digitise historical locations, streets, or enumeration units directly on geo-referenced historical maps, in either a manual or semi-automatic way. Gregory et al. [

8] have digitised administrative boundary maps in the UK from 1906 to 1910 and used the results to develop a series of thematic maps, for example, the mortality rate from lung disease by registration districts. To extract locations and social classifications of households in historical London, Orford et al. [

14] have manually digitised about 120,000 points from the Charles Booth’s poverty map. Logan et al. [

4] have geo-referenced the addresses from the 1880 U.S. Census by editing the U.S. TIGER (Census Bureau’s Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing System) files. Combining both modern census geography and various historical data sources, St-Hilaire et al. [

3] have reconstructed the census subdivision polygons for the 1911–1951 Canadian censuses and associated other census variables to these polygons. The advent of crowdsourcing and web-GIS techniques has enabled public engaged geocoding practices. With the assistance of a web-based volunteered geographic information (VGI) system, Southall et al. [

15] have created a historical gazetteer of Great Britain for the c. 1900s by pinpointing text annotations of jurisdictions, places, streets and other points of interest using a series of geo-referenced Ordnance Survey (OS) maps. Likewise, Cura et al. [

16] have established an online VGI geocoding system of historical Paris based on their Historical Geocoder, to collaboratively enhance geocoding results of computer vision and machine learning algorithms. There are other geocoding packages similar to the Historical Geocoder, for example, Pelias and Nominatim.

Another strategy is to run text-based address matching between historical data sources and address databases that have already been geo-referenced. The most common geo-referencing method is to associate census attributes to specific enumeration geographies for mapping and analysing purposes. For instance, Carrion et al. [

17] create a spatial database for medieval fiscal data in Italy by matching the place names to present-day geographies. Clough et al. [

18] summarise several sources of existing geocoded data assets for linking the UK National Archive’s data to geographical locations. There are also cases which geo-reference historical data at the record level rather than at the aggregated level. Daras et al. [

19] have presented their results of geocoding 24 million births, marriages, and deaths records from 1855 to 1974 in the Digitising Scotland project. Walford [

20] has devised a semi-automated geocoding method for addresses in six pilot study areas within the modern Greater London Authority area based upon 1901 and 1911 Census data. Lansley et al. [

21] have linked the addresses from twenty years’ residential addresses from consumer registers to the OS AddressBase product. These various projects demonstrate that a considerable amount of historical addresses can be matched to modern address databases, despite the fact that entire areas, as well as individual properties, may have been redeveloped over the intervening years.

The two strategies each have their advantages and disadvantages. Digitising and geo-referencing addresses on historical maps usually achieve higher spatial consistency, notwithstanding the cost of intensive human labour. VGI solutions mitigate costs. In contrast, the address matching strategy enables automated geo-referencing processes, suitable for large numbers of records, as with geocoding of entire nation census records. However, the address matching process is vulnerable to the quality of the address strings that may be ambiguous or error-prone, for example, when street numbers are changed or re-sequenced over time. In this paper, we aim to geo-reference millions of historical census addresses at the micro level for further spatial analysis, without the commitment of resources required in digital encoding from historical paper sources. Where available, we utilise existing assets of geocoded address corpora alongside the primary strategy of linking historical census addresses to existing databases.

3. Data and Methods

Twelve digitally encoded Great Britain census datasets were obtained from the UK Data Service (UKDS) under a special licence agreement, pertaining to England and Wales or Scotland over the period 1851–1911. The data are enhanced versions of the original Census return transcriptions, enriched by the Integrated Census Microdata project (I-CeM) [

1]. In this paper, we take only the 1901 Census in England and Wales as an example to illustrate our geo-referencing process. There were 32,493,318 individuals enumerated in the 1901 Census in England and Wales. Residential addresses were reported in the unit of a household or an institution.

Table 1 presents some address instances from the 1901 Census. Column “RECID” stores the unique record identifiers while “CONPARID” is the ID of the parish to which the record belongs. Some of the addresses in urban parishes are clearly formatted into street number(s) and thoroughfare names, such as “10 Gower Street” or “10 Cardiff Road”. By contrast, others are more descriptive, such as the “house on police station”. In rural parishes, some addresses are simply place names, for example “old mill”. Many addresses in Wales are recorded in Welsh, as illustrated in

Table 1.

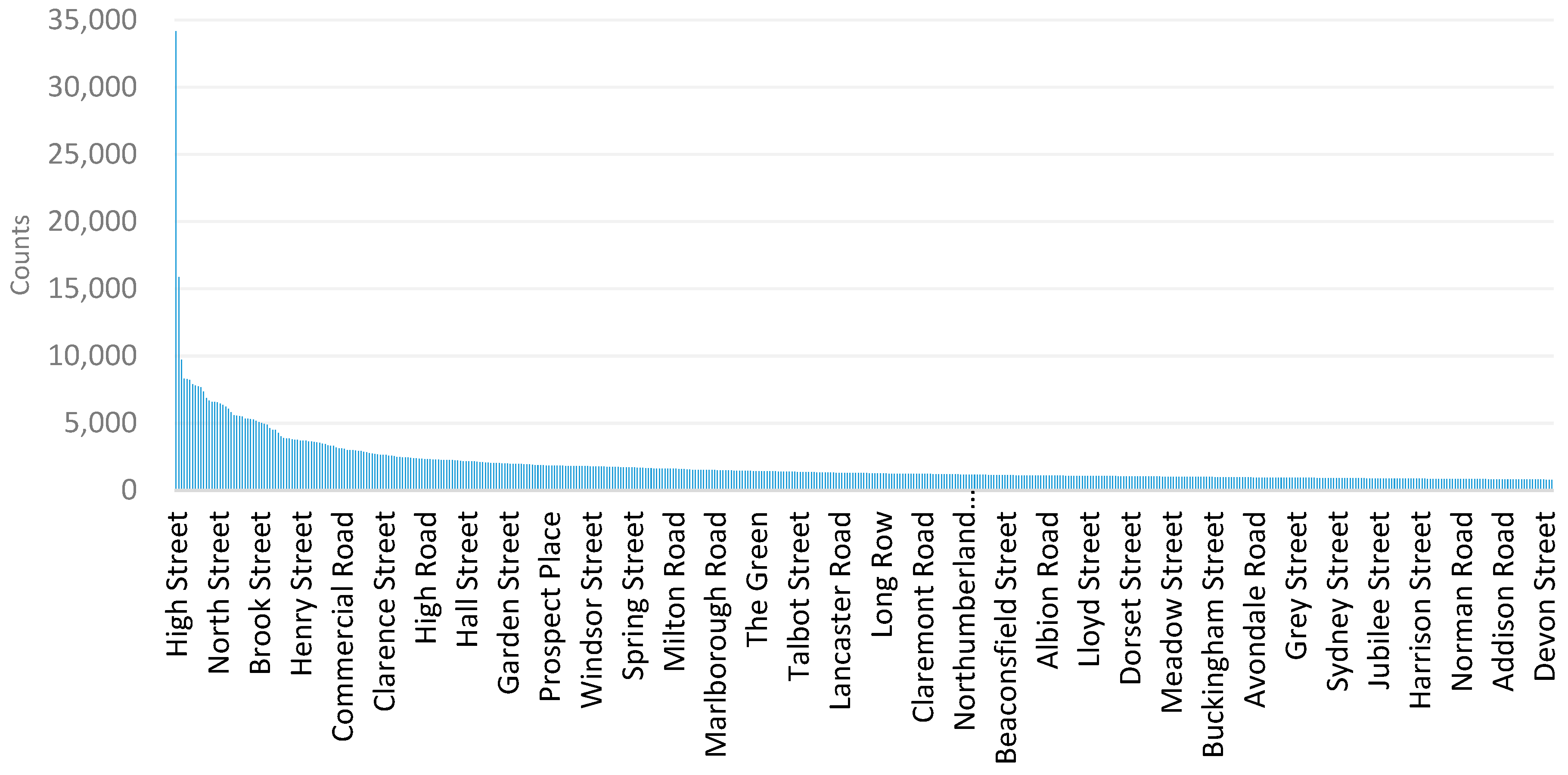

In addition to the previously mentioned challenges, common street names pose another issue for address matching. To explore the diversity of street names in the Census address, we extract street names and summarise their frequency distribution. The 10 most frequently used street names in the 1901 Census are High Street, Church Street, Queen Street, George Street, King Street, Victoria Street, West Street, Station Road, Chapel Street, and Victoria Road. These reflect interesting features in the nomenclature of streets in the Nineteenth Century. For instance, to commemorate the monarchy, streets across the country were often named after the monarch or Royal Family. There are 703,263 unique street names across England and Wales.

Figure 1 plots the frequency distribution of the most popular 500 street names, and exhibits a truncated long tail pattern. Beyond the frequent occurrences, such as the 34,145 High Street and 15,874 Church Street addresses, there is a long tail of unique occurrences such as “furniture shop 37 eagle street”.

Besides the historical Census addresses, we have two corpora of geocoded addresses: the contemporary OS AddressBase Premium (

https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-and-government/products/addressbase-premium.html) and the historical GB1900 Gazetteer (

http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/data/). OS AddressBase is the most comprehensive address database maintained for Great Britain, comprising 28 million Royal Mail postal delivery addresses plus inputs from the planning system maintained by local authorities. These addresses are consistently structured and are geocoded, providing a reliable spine against which historical address data may be matched. However, many historical addresses are messy, particularly in rural areas where addresses are frequently reported as place names, street names, or farm names, often in non-standardised, non-hierarchical formats. Moreover, past place names or street names may be altered or fall into disuse. In an attempt to identify and accommodate such instances, we incorporate the historical GB1900 Gazetteer. This gazetteer of street and place names is the outcome of transcription and geocoding of scanned OS County Series covering Great Britain from the early 1900s, using the contributions of thousands of volunteers over years in the GBHGIS project [

15,

22]. There are c. 2.6 million geo-referenced text strings, which have been transcribed and confirmed then by different transcribers to guarantee the data quality. This is likely to be the largest open historical gazetteer online so far [

15] and can be accessed via the website ‘A Vision of Britain through Time’ (

http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/data/).

Figure 2 shows the flow of the two-stage data processing in this paper. We take the addresses from the 1901 Census in England and Wales, the OS AddressBase, and the GB1900 Gazetteer as the data input. We also assign historical parish identifiers to addresses in both the OS AddressBase and the GB1900 Gazetteer, by spatially joining them to historical parish boundary data, provided by the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure (

https://www.campop.geog.cam.ac.uk/). We adopt a geo-blocking strategy, searching only for candidate address pairs within the same parishes from the historical addresses and the geocoded addresses in the two address corpora. There are 4,872,707 address strings in total that are unique within each parish in England and Wales. We thus go some way towards resolving multiple occurrences of common street names and reduce the high computation cost of fuzzy string matching.

After cleaning the historical addresses, we extract unique address strings within each parish from both the historical addresses and the OS AddressBase. We further split these address strings into street numbers and thoroughfare names in order to get unique street names by parish. Taking advantage of the open source package Fuzzywuzzy (

https://github.com/seatgeek/fuzzywuzzy), we link the historical street names to their most probable matches within the relevant parish found in AddressBase. We then check whether street numbers can be matched in addition to street names. A historical address is considered matched at the address level if both street name and number are found in the same parish in AddressBase. Likewise, an address is considered as being matched only at the street level if naming or numbering is inconsistent in the same parish. Whilst this procedure does not accommodate street re-numbering, the results are deemed sufficiently consistent for our present purposes.

For historical addresses that are not matched at either level, we implement a parish-level fuzzy matching procedure as an additional stage. It is worth noting that the encoding of the address strings from the historical censuses and the geocoded address corpus should be unified in advance to facilitate the fuzzy string matching, since address strings in Welsh sometimes appear in Unicode, which may inhibit string comparisons.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

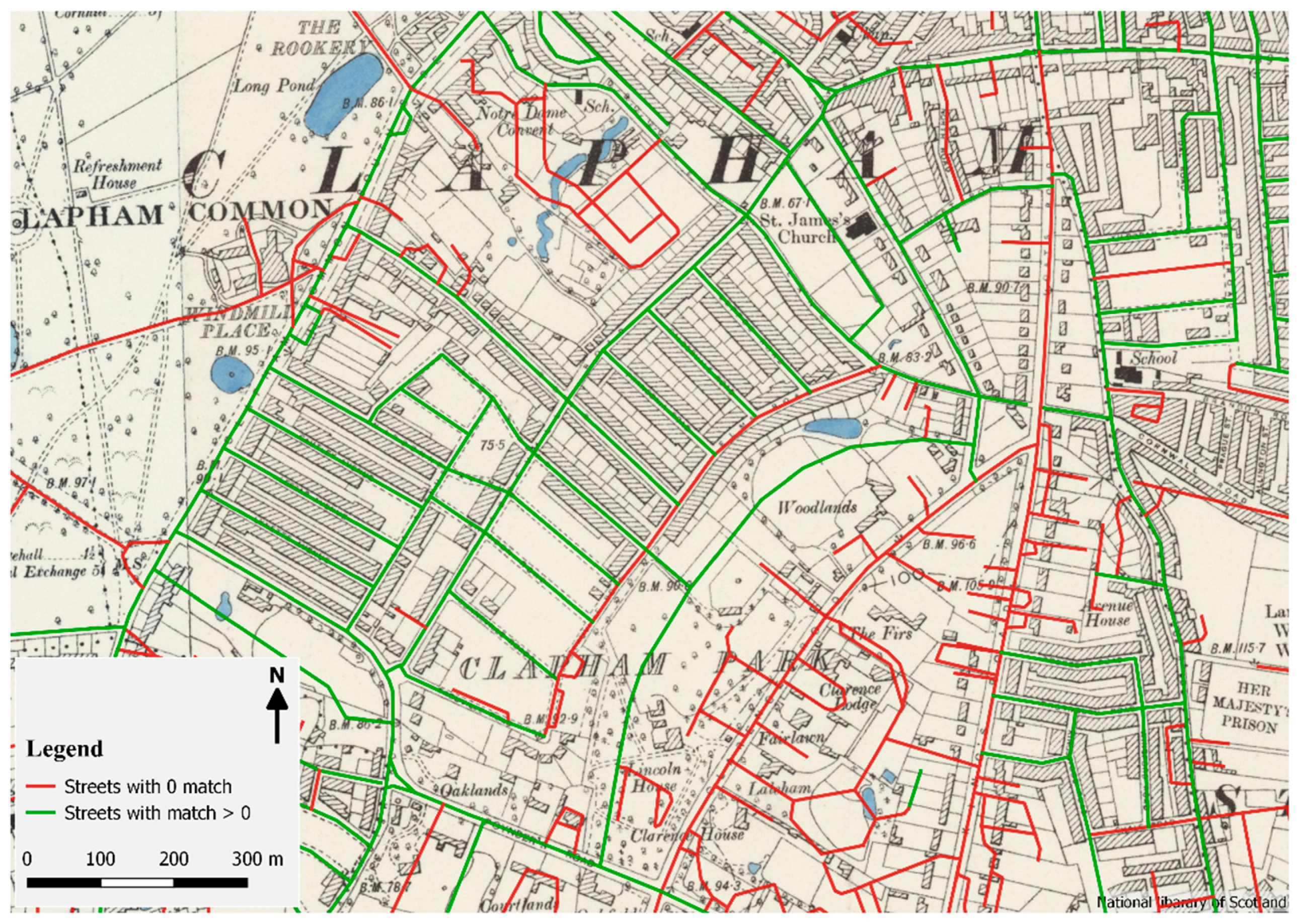

In this paper, we present our experience of geo-referencing historical addresses from the 1901 Census in England and Wales at a range of scales from the national to the local. We develop a two-stage address matching method, employing the geocoded contemporary and historical address corpora. We achieve an overall match rate of 85% (4,132,117 addresses) at varying levels covering 79.7% (25,882,022 people) of the entire population of England and Wales in 1901, which shows it is feasible to geo-reference a large share of historical census addresses with the proposed method.

The vast majority of the matched addresses (63%) are successfully linked to the contemporary AddressBase at the first stage. While this is by no means proof of linkage of the same built structure, it does demonstrate success in linking locations with high apparent spatial precision and provides a basis for evaluation of possible anomalies, such as streets that today have different number ranges or nomenclatures to those observed in 1901. The highest match rates to the contemporary AddressBase are concentrated in the historical cores of towns and cities. In absolute terms, this, of course, reflects the high concentrations of addresses in urban areas, but it is also clear that it was in urban areas that standard address referencing first emerged. The difference between urban and rural match rates also has been reflected in terms of the occupational distribution. We find the group of people conducting agricultural and forestry tasks is slightly underrepresented in the population with geocoded addresses with respect to other occupational groups. Apart from this, there is no serious bias among other groups.

Comparison of the mapped matches also provides broad brush indications of the nature and extent of redevelopment processes over the last 100+ years, as well as the effects of national and local planning systems in guiding or restricting development. At national levels, comparison of the periods also indicates the ravages of World War Two and subsequent redevelopment processes. Similar practices of linking historical addresses to the present address registers have been developed both in Scotland and England [

19,

20].

Linkage of historical census data to the current OS AddressBase misses some pieces of the historical address jigsaw. The GB1900 Gazetteer of Great Britain complements the OS AddressBase by geo-referencing an additional 22% of census addresses, drawn principally from rural parishes. Moreover, the Gazetteer also succeeds in matching a large number of addresses in the Welsh language by converting address strings into Unicode. Based on the observations, we find that modern address registers and historical gazetteers together appear to be two useful and complementary data sources for geo-referencing historical addresses. We currently have around 15% unmatched historical addresses, most of which are in rural parishes. Some of these could be linked through labour-intensively manual intervention, although our impression is that some Census records are simply too ambiguous to be linked with a high level of confidence.

One limitation of this work is the lack of validation of the matched results. Further spatial analysis of the geocoded censuses could be influenced by geocoding quality such as positional errors [

25,

26]. To date, we have only checked the outcome of matching in a few areas, but there is clear scope to use manual, semi-automated and automated methods in order to highlight and ultimately to accommodate anomalies in the matching process. This is clearly a fertile topic for future research.

In the context of other historical GIS and spatial humanities projects, geo-referencing is only a starting point of introducing further spatial analysis into geo-temporal demographic analysis. In addition to addresses, the historical censuses in England, Wales and Scotland provide a set of informative characteristics of residents, including population counts, demographics, household structure, occupation, fertility and disabilities. Geo-referencing of the historical census records spatially enables an intriguing range of topics in digital humanities and creates a framework for geo-temporal analysis where data from successive censuses can be linked. In our future research, we propose to apply automated techniques [

21] developed for linking recent national consumer registers [

27] to the similar linkage of historical census data. This agenda encompasses developing new geo-temporal demographics, migration analysis, segregation studies and an over-arching analysis of processes and patterns of social and spatial mobility in Great Britain.