The Cultural Heritage and the Shaping of Tourist Itineraries in Rural Areas: The Case of Historical Ensembles of Extremadura, Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case Study

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Service Area

2.2.2. Closest Facility

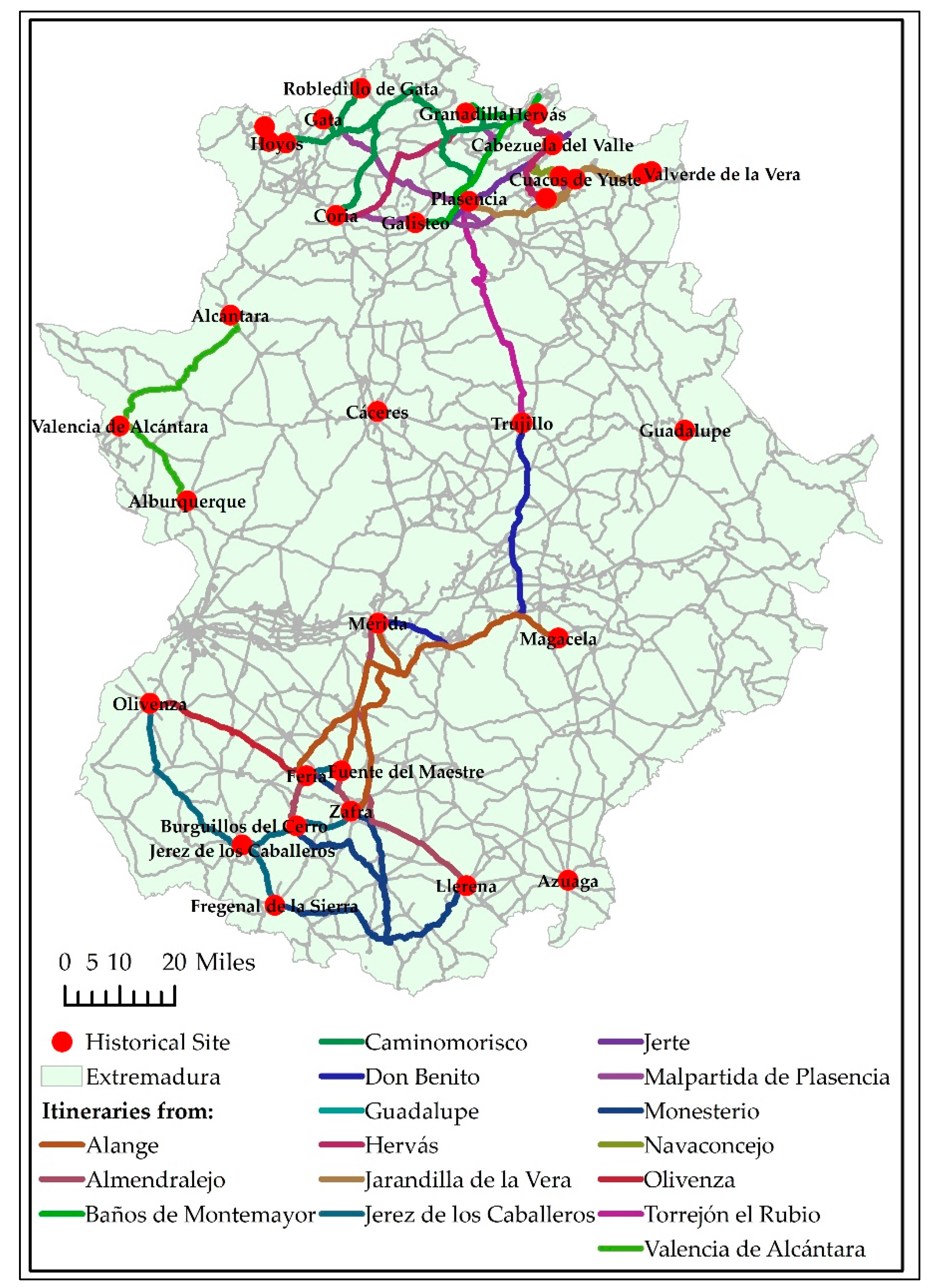

2.2.3. The Creation of Itineraries

3. Results

3.1. Tourist Types

3.2. Historical Ensembles as Potential Centers for Attracting Demand (Service Area)

3.3. Nearby Historical Ensembles as Areas of Expansion for the Tourist Experience (Closest Facility)

3.4. Designing Cultural Itineraries in the Rural Milieu

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prats, L. El concepto de patrimonio cultural. Política Soc. 1998, 27, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, N. Culturas Híbridas: Estrategias para Entrar y Salir de la Modernidad; Paidós: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005; 349p. [Google Scholar]

- Prats, L.; Santana, A. Reflexiones libérrimas sobre patrimonio, turismo y sus confusas relaciones. In El Encuentro del Turismo con el Patrimonio Cultural: Concepciones Teóricas y Modelos de Aplicación; Prats, L., Santana, A., Eds.; Fundación El Monte: Sevilla, Spain, 2005; pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fontal, O. La educación patrimonial. Teoría y Práctica en el Aula, el Museo e Internet; Trea: Gijón, España, 2004; p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan, Y. Heritage, Memory and the Politics of Identity: New Perspectives on the Cultural Landscape; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; 168p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, D. Cultural Heritage and the Challenge of Sustainability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; 222p. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, P.B.; Logn, W. World Heritage and Sustainable Development. New Directions in World Heritage Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; 310p. [Google Scholar]

- González, I. Conservación de Bienes Culturales. Teoría, Historia, Principios y Normas; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2006; 632p. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Xu, H. Cultural heritage elements in tourism: A tier structure from a tripartite analytical framework. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, E. Sobre patrimonio y desarrollo. Aproximación al concepto de patrimonio cultural y su utilización en procesos de desarrollo territorial. 1, 2011, Pasos. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2011, 9, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, E. De tesoro ilustrado a recurso turístico: El cambiante significado del patrimonio cultural. Pasos. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2006, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Nyaupane, G.P. Cultural Heritage and Tourism in the Developing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; 280p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Calle, M.; García, M. Ciudades históricas: Patrimonio cultural y recurso turístico. Ería 1998, 47, 249–266. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/34879.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Troitiño, M.A. Turismo y ciudades históricas. Retos y oportunidades. Tur. Patrim. 2000, 1, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, B.; Lois, R.C.; Lopez, L.; Ahmad, R.; Hertzog, A. Historic city, tourism performance and development: The balance of social behaviours in the city of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 16, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, A. Patrimonio inmaterial, recurso turístico y espíritu de los territorios. Cuad. Tur. 2001, 27, 663–677. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/140151/126251 (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Hernández, J. Los caminos del patrimonio. Rutas e itinerarios culturales. Pasos. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2011, 9, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcal, M.C. El patrimonio rural como recurso turístico. La puesta en valor turístico de infraestructuras territoriales (rutas y caminos) en las áreas de montaña del País Vasco y de Navarra. Cuad. Tur. 2011, 27, 759–784. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/140211/126361 (accessed on 19 December 2019).

- Cañizares, M.C. La “Ruta de Don Quijote” en Castilla-La Mancha (España): Nuevo itinerario cultural europeo. Nimbus 2008, 21–22, 55–75. Available online: http://repositorio.ual.es/bitstream/handle/10835/1510/Ca%C3%B1izares%20Ruta.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Ghimire, K.B.; Pimbert, M.P. Social change and conservation; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008; 341p. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D.; Hitchconck, M. The Politics of World Heritage. Negotiating Tourism and Conservation; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2005; 192p. [Google Scholar]

- Dallen, J.T.; Gyan, P.N. Cultural Heritage and Tourism in the Developing World: A Regional Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño Vinuesa, M.A.; Troitiño Torralba, L. Patrimonio y turismo: Reflexión teórico-conceptual y una propuesta metodológica integradora aplicada al municipio de Carmona (Sevilla, España). Scr. Nova 2019, 20, 1–45. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-543.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- Brandis, D. La imagen cultural y turística de las Ciudades Españolas Patrimonio de la Humanidad. In Ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad: Patrimonio, Turismo y Recuperación Urbana; Troitiño, M.A., Ed.; Universidad Internacional de Andalucía/Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2009; pp. 72–99. [Google Scholar]

- Collin Harguindeguy, L. La transformación del patrimonio cultural en recurso turístico. Rev. Andal. Antropol. 2019, 16, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prats, F. Sostenibilidad y turismo, una simbiosis imprescindible. Estud. Turísticos 2007, 173, 13–66. Available online: http://www.iet.tourspain.es/img-iet/revistas/ret-172-173-2007-pag13-62-101045.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Loulanski, T.; Loulanski, V. The sustainable integration of cultural heritage and tourism: A meta-study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 837–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Heritage tourism: The contradictions between conservation and change. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2003, 4, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelman, I. Critiques of island sustainability in tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, M.; Planells, M. Recursos turísticos; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2011; 424p. [Google Scholar]

- Martos, M. Las ciudades patrimoniales en el mercado turístico cultural. Úbeda y Baeza. Gran Tour. Rev. Investig. Turísticas 2012, 6, 63–82. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4172823.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2019).

- González, S.; Querol, M.A. El patrimonio inmaterial. Rev. PH 2015, 88, 306–307. Available online: http://www.iaph.es/revistaph/index.php/revistaph/article/view/3626/3697 (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Rengifo, J.I. Rutas culturales y turismo en el contexto español. PH Boletín Inst. Andal. Patrim. 2006, 60, 114–125. Available online: http://www.iaph.es/revistaph/index.php/revistaph/article/view/2263/2263 (accessed on 5 December 2019). [CrossRef]

- Cisne, R.; Gastal, S. Nueva visión sobre los itinerarios turísticos. Una contribución a partir de la complejidad. Estud. Y Perspect. En Tur. 2011, 20, 1449–1463. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1807/180722700012.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Mascarenhas, R.G.; Gândara, J.M. Producción y transformación territorial. La gastronomía como atractivo turístico. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2010, 19, 776–791. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/3352414.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Código Civil y Legislación Complementaria. Available online: https://www.boe.es/legislacion/codigos/codigo.php?id=034_Codigo_Civil_y_legislacion_complementaria (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Ley 13/85 del Patrimonio Histórico Español. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/1985/06/29/pdfs/A20342-20352.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte. Gobierno de España. Base de datos de Bienes Muebles. Available online: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/bienes/cargarFiltroBienesMuebles.do?layout=bienesMuebles&cache=init&language=es (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte. Gobierno de España. Base de datos de Bienes Inmuebles. Available online: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/bienes/cargarFiltroBienesInmuebles.do?layout=bienesInmuebles&cache=init&language=es (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Ley 45/2007, para el desarrollo sostenible del medio rural. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2007/12/13/45/con (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Sánchez, J.M.; Sánchez, M. Sinergias turísticas en entornos rurales: Entre el mito y la realidad. El caso del Geoparque Villuercas-Ibores-Jara. In X Citurdes: Congreso Internacional de Turismo Rural y Desarrollo Sostenible, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 19-21 October 2016; Santos, X.M., Taboada, P., Lopez, L., Eds.; UFRGS, USC, ANTE, Grupo Mercados Nâo Agrícolas Rurais: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2016; pp. 433–448. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I. Los espacios naturales protegidos y su capacidad de atracción turística: Referencias al Parque Nacional de Monfragüe (Extremadura-España). In Proceedings of the APDR; Universidade de Beira Interior; RSAI; ERSA, Intellectual Capital and Regional Development: New Landscapes and Challenges for Space Planning, Covilhâ, Portugal, 6–7 July 2017; pp. 1196–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I.; Martín, L.M. Tourist mobility at the destination toward protected areas: The case-study of extremadura. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I.; Sánchez, M. Caracterización espacial del turismo en Extremadura mediante análisis de agrupamiento (grouping analysis). Un ensayo técnico. Geofocus. Rev. Int. Cienc. Tecnol. Inf. Geográfica 2017, 19, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Blas, R.; Rengifo, J.I. The dehesas of extremadura, Spain: A potential for socio-economic development based on agritourism activities. Forests 2019, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Sánchez, M.; Rengifo, J.I. La evaluación del potencial para el desarrollo del turismo rural. Aplicación metodológica sobre la provincia de Cáceres. Geofocus: Rev. Int. Cienc. Tecnol. Inf. Geográfica 2013, 13, 99–130. Available online: http://www.geofocus.org/index.php/geofocus/article/view/263 (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Rengifo, J.I.; Sánchez, J.M. El patrimonio en Extremadura: Un mecanismo para la cooperación transfronteriza. Polígonos. Rev. Geogr. 2017, 29, 223–248. Available online: http://revpubli.unileon.es/ojs/index.php/poligonos/article/view/5207 (accessed on 15 December 2019). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, R.; Bramwell, B.; Whalley, P.A. Cultural political economy and urban heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 68, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srijuntrapun, P.; Fisher, D.; Rennie, H.G. Assessing the sustainability of tourism-related livelihoods in an urban World Heritage Site. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.; de la Calle, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural heritage and urban tourism: Historic city centres under pressur. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shoval, N. Urban planning and tourism in European cities. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Choi, B.K.; Lee, T.J. The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logothetis, S.; Stylianidis, E. BIM open source software (OSS) for the documentation of cultural heritage. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2016, 7, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tscheu, F.; Buhalis, D. Augmented reality at cultural heritage sites. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Inversini, A., Schegg, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovcheva, Z.; Buhalis, D.; Gatzidis, C. Engineering augmented reality tourism experiences. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Cantoni, L., Xiang, Z., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Vienna, Austria, 2015; pp. 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, M.; Pierdicca, R.; Frontoni, E.; Malinverni, E.; Gain, J. A survey of augmented, virtual, and mixed reality. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2018, 11, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B.; Buhalis, D.; Ladkin, A. A typology of technology-enhanced tourism experiences. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, F.Z. La Convención Europea del Paisaje y su aplicación en España. Ciudad Territ. 2001, 128, 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2008. Recomendación CM/Rec(2008)3 del Comité de Ministros a los Estados miembro sobre las orientaciones para la aplicación del Convenio Europeo del Paisaje. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/desarrollo-rural/planes-y-estrategias/desarrollo-territorial/09047122800d2b4d_tcm30-421588.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Silva Pérez, R. La dehesa vista como paisaje cultural. Fisionomías, funcionalidades y dinámicas históricas. Ería 2010, 82, 143–157. Available online: https://www.unioviedo.es/reunido/index.php/RCG/article/view/1691/1585 (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Guzmán Álvarez, J.R. The image of a tamed landscape: Dehesa through history in Spain. Cult. Hist. Digit. J. 2016, 5, e003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Cacho, S. La dimensión paisajística en la gestión del patrimonio cultural en España. Estud. Geográficos 2019, 80, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cruz Pérez, L. El agua como elemento generador de paisajes culturales: Una visión desde el Plan Nacional de Paisaje Cultural. In Paisajes Culturales del Agua; Lozano Bartolozzi, M.M., Méndez Hernán, V., Eds.; Universidad de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 2017; pp. 17–36. Available online: http://dehesa.unex.es/bitstream/handle/10662/6703/978-84-697-4487-1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Naranjo, F.Z. Los paisajes como patrimonio natural y cultural. In I Congreso Internacional “El Patrimonio cultural y natural como motor de desarrollo: Investigación e innovación”; Peinado Herreros, M.A., Ed.; Universidad Internacional de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 2012; pp. 626–644. Available online: http://dspace.unia.es/bitstream/handle/10334/3456/2012_Congresointernacional.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Fanfani, D.; Matarán Ruiz, A. La aplicación del Convenio Europeo del Paisaje en España e Italia: Un análisis crítico de los casos andaluz y toscano. Rev. Electrónica Patrim. Histórico 2010, 6, 1–15. Available online: https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/erph/article/view/3372/3384 (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Rengifo, J.I.; Sánchez, J.M. Atractivos naturales y culturales vs. desarrollo turístico en la raya Luso-Extremeña. Pasos: Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2016, 14, 907–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Hoteles: Encuesta de ocupación, índice de precios e indicadores de rentabilidad. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/es/index.htm?padre=238&dh=1 (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Sánchez-Rivero, M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.-I. Water as a tourist resource in Extremadura: Assessment of its attraction capacity and approximation to the tourist profile. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN). Available online: http://www.ign.es/web/resources/docs/IGNCnig/CBG%20-%20BTN100.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Junta de Extremadura. Extremadura Turismo. Available online: http://www.turismoextremadura.com/es/organiza-tu-viaje/donde-alojarse/index.html (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Mckercher, B.; Lau, G. Movement patterns of tourists within a destination. Tour. Geogr. 2008, 10, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoltan, J.; McKercher, B. Analysing intra-destination movements and activity participation of tourists through destination card consumption. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Sun, S.; Law, R. Movement patterns of tourists. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chante, A.; Fuentes, L.; Muñoz, A.; Ramírez, G. Science mapping of tourist mobility 1980–2019. technological advancements in the collection of the data for tourist traceability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viamichelin. Available online: https://www.viamichelin.es (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Indriasari, V.; Mahmud, A.; Anmad, N.; Shariff, A. Maximal service area problem for optimal siting of emergency facilities. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xia, B.; Wu, H.; Zhao, J.; Peng, Z.; Yu, Y. Delimitating the natural city with points of interests based on service area and maximum entropy method. Entropy 2019, 21, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Kwan, M.P. Hexagon-based adaptive crystal growth voronoi diagrams based on weighted planes for service area delimitation. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ESRI. Available online: https://desktop.arcgis.com/es/arcmap/latest/extensions/network-analyst/service-area.htm (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Love, D.; Lindquist, P. The geographical accessibility of hospitals to the aged: A geographic information systems analysis within Illinois. Health Serv. Res. 1995, 29, 629–651. Available online: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA16745151&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=fulltext&issn=00179124&p=AONE&sw=w (accessed on 12 December 2019). [PubMed]

- AwaghadeII, S.; DandekarI, P.; Ranade, P. Site selection and closest facility analysis for automated teller machine (ATM) centers: Case study for Aundh (Pune), India. Int. J. Adv. Remote Sens. GIS Geogr. 2014, 2, 19–29. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.671.562&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Drezner, T. Locating a single new facility among existing, unequally attractive facilities. J. Reg. Sci. 1994, 34, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ReVelle, C.S.; Eiselt, H.A. Location analysis: A synthesis and survey. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2005, 165, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Available online: http://www.ine.es/FichasWeb/RegComunidades.do?fichas=49&busc_comu=&botonFichas=Ir+a+la+tabla+de+resultados (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- UNWTO. Tourism and Culture. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-and-culture (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- Zhao, X.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Lin, J.; An, J. Tourist movement patterns understanding from the perspective of travel party size using mobile tracking data: A case study of Xi’an, China. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.; McKercher, B. Modeling tourist movements: A local destination analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asero, V.; Gozzo, S.; Tomaselli, V. Building tourism networks through tourist mobility. J. Travel Res. 2015, 55, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, L.; Zoltan, J. Tourists intra-destination visits and transport mode: A bivariate probit model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M. Anuario de Oferta y Demanda Turística de Extremadura por Territorios. Año 2017; Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, Spain, 2018; 87p, Available online: https://www.turismoextremadura.com/.content/observatorio/2017/EstudiosYMemoriasAnuales/Anuario_oferta-demanda2017.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Bec, A.; Mayole, B.; Timms, K.; Schaffer, V.; Skavronskaya, L.; Little, C. Management of immersive heritage tourism experiences: A conceptual model. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, R.; Khoo, C. New realities: A systematic literature review on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2056–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S. Augmented reality enhancing place satisfaction for heritage tourism marketing. 2019. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T. A theoretical model of mobile augmented reality acceptance in urban heritage tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghermandi, A.; Camacho, V.; Trejo, H. Social media-based analysis of cultural ecosystem services and heritage tourism in a coastal region of Mexico. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inskeep, E. Tourism planning: An emerging specialization. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1988, 54, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships; Pearson: London, UK, 2008; 303p. [Google Scholar]

- Mise, S. The role of spatial models in tourism planning. In New Metropolitan Perspectives. ISHT 2018. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, 100; Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Bevilacqua, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrđa, A.; Carić, H. (2019) Models of heritage tourism sustainable planning. In Cultural Urban Heritage; The Urban Book Series; Obad Šćitaroci, M., Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B., Mrđa, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, D.M.; Arcila, M.L.; López, J.A. Las Rutas e Itinerarios Turístico-Culturales en los Portales Oficiales. Rev. De Estud. Andal. 2018, 35, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishmanova, M.V. Cultural tourism in cultural corridors, itineraries, areas and cores networked. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mcadam, D. The value and scope of geographical information systems in tourism management. J. Sustain. Tour. 1999, 7, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Choy, J.-Y.; Yoo, S.-H.; Oh, Y.-G. Evaluating spatial centrality for integrated tourism management in rural areas using GIS and network analysis. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W. Research on the application of geographic information system in tourism management. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 12, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inanc, M.; Kozak, M. Big data and its supporting elements: Implications for tourism and hospitality marketing. In Big Data and Innovation in Tourism, Travel, and Hospitality; Sigala, M., Rahimi, R., Thelwall, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, K.A.; Darma, G.S. Community-based tourism: Measuring readiness of artificial intelligence on traditional village. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 3, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres Bernier, E. Rutas culturales. Recurso, destino y producto turístico. PH Boletín Del Inst. Andal. Del Patrim. Histórico 2006, 60, 84–97. Available online: http://www.iaph.es/revistaph/index.php/revistaph/article/view/2259/2259 (accessed on 27 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- Garrido, M.A.; Sánchez, J.L.; Enriquez, A.F. Rutas turísticos-culturales e itinerarios culturales como productos turísticos: Reflexiones sobre una metodología para su diseño y evaluación. In Análisis Espacial y Representación Geográfica: Innovación y Aplicación; de la Riva, J., Ibarra, P., Montorio, R., Rodrigues, M., Eds.; Universidad de Zaragoza: Aragon, Spain, 2015; pp. 463–471. Available online: http://congresoage.unizar.es/eBook/trabajos/049_Arcila%20Garrido.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Sáenz Saavedra, N. Los sistemas de información geográfica (SIG) una herramienta poderosa para la toma de decisiones. Ing. E Investig. 1992, 28, 31–40. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4902930.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Bosque Sendra, J. Planificación y gestión del territorio. De los SIG a los sistemas de ayuda a la decisión espacial (SADE). El Campo De Las Cienc. Y Las Artes 2001, 138, 137–174. Available online: https://geogra.uah.es/joaquin/pdf/SIG-y-SADE.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I.; Sánchez, M. Protected areas as a center of attraction for visits from world heritage cities: Extremadura (Spain). Land 2020, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Area | Travelers | Spanish Travelers | Foreign Travelers | Overnight Stays | Average Stay | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Heritage Cities 1 | 536,348 | 437,571 | 98,777 | 836,046 | 1.56 | |

| Other cultural cities 1 | 449.525 | 363,666 | 85,859 | 737,253 | 1.64 | |

| Northern area of Extremadura 2 | Hotels | 267,803 | 228,587 | 39,216 | 544,814 | 2.03 |

| Rural accommodation | 123,302 | 117,733 | 5569 | 283,149 | 2.30 | |

| Camping | 71,875 | 62,511 | 9364 | 213,062 | 2.96 | |

| Historical Ensemble | Population (2018) | Beds Available (2018) | Is It an Important Tourist Center Due to the Number of Its Overnight Stays? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hotel | Non Hotel | Rural | Total | |||

| Alburquerque | 5340 | 51 | 0 | 33 | 84 | Yes |

| Alcántara | 1480 | 118 | 0 | 34 | 152 | Yes |

| Azuaga | 7891 | 102 | 27 | 14 | 143 | Yes |

| Burguillos del Cerro | 3085 | 41 | 0 | 120 | 161 | No |

| Cabezuela del Valle | 2151 | 46 | 64 | 97 | 207 | Yes |

| Cáceres *† | 96,068 | 2481 | 1104 | 24 | 3609 | Yes |

| Coria | 12,531 | 193 | 0 | 0 | 193 | Yes |

| Cuacos de Yuste | 846 | 50 | 388 | 162 | 600 | No |

| Feria | 1150 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 45 | No |

| Fregenal de la Sierra | 4918 | 106 | 0 | 60 | 166 | No |

| Fuente del Maestre | 6774 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 34 | No |

| Galisteo | 953 | 43 | 8 | 0 | 51 | No |

| Garganta la Olla | 984 | 12 | 0 | 59 | 71 | No |

| Gata | 1493 | 24 | 6 | 42 | 72 | No |

| Guadalupe ** | 1887 | 418 | 250 | 91 | 759 | Yes |

| Hervás | 4052 | 225 | 1484 | 267 | 1976 | Yes |

| Hoyos | 906 | 18 | 10 | 27 | 55 | No |

| Jerez de los Caballeros | 9367 | 201 | 68 | 54 | 323 | Yes |

| Llerena | 5758 | 148 | 0 | 52 | 200 | Yes |

| Magacela | 526 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 25 | No |

| Mérida *† | 59,352 | 1844 | 649 | 12 | 2505 | Yes |

| Olivenza | 11,986 | 337 | 4 | 0 | 341 | Yes |

| Pasarón de la Vera | 641 | 0 | 8 | 62 | 70 | No |

| Plasencia † | 40,141 | 934 | 545 | 19 | 1498 | Yes |

| Robledillo de Gata | 91 | 0 | 0 | 87 | 87 | No |

| San Martín de Trevejo | 788 | 57 | 0 | 76 | 133 | No |

| Trevejo (Villamiel) | 10 (426) | 0 | 0 | 71 | 71 | No |

| Trujillo† | 9193 | 983 | 127 | 103 | 1,213 | Yes |

| Valencia de Alcántara | 5439 | 112 | 12 | 235 | 359 | Yes |

| Valverde de la Vera | 460 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 64 | Yes |

| Villanueva de la Vera | 2046 | 20 | 39 | 137 | 196 | Yes |

| Zafra† | 16,776 | 683 | 4 | 28 | 715 | Yes |

| Zarza de Granadilla | 1823 | 16 | 20 | 75 | 111 | No |

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | X7 | X8 | X9 | X10 | X11 | X12 | X13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| X2 | 0.029 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| X3 | 0.044 ** | 0.035 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| X4 | 0.061 ** | 0.033 ** | 0.040 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| X5 | 0.051 ** | 0.047 ** | 0.082 ** | 0.175 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| X6 | −0.003 | 0.041 ** | −0.042 ** | −0.031 ** | 0.028 ** | 1 | |||||||

| X7 | 0.027 ** | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.048 ** | 0.077 ** | −0.010 | 1 | ||||||

| X8 | 0.019 * | 0.004 | 0.055 ** | 0.157 ** | 0.117 ** | −0.057 ** | 0.051 ** | 1 | |||||

| X9 | 0.019 * | 0.008 | 0.066 ** | 0.094 ** | 0.071 ** | −0.079 ** | 0.046 ** | 0.194 ** | 1 | ||||

| X10 | 0.072 ** | 0.059 ** | 0.179 ** | 0.056 ** | 0.061 ** | 0.010 | −0.015 | 0.014 | 0.004 | 1 | |||

| X11 | 0.053 ** | 0.034 ** | 0.076 ** | 0.050 ** | 0.088 ** | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.048 ** | 0.003 | 0.046 ** | 1 | ||

| X12 | 0.027 ** | 0.038 ** | 0.047 ** | 0.084 ** | 0.099 ** | −0.003 | 0.026 ** | 0.110 ** | 0.070 ** | 0.117 ** | 0.029 ** | 1 | |

| X13 | 0.019 * | −0.030 ** | 0.145 ** | −0.037 ** | −0.012 | −0.097 ** | −0.096 ** | −0.027 ** | −0.099 ** | 0.052 ** | 0.028 ** | 0.016 | 1 |

| Category 1 (0 min) | Category 2 (20 min) | Category 3 (45 min) | Category 4 (More than 45 min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alburquerque | Garganta la Olla | Burguillos del Cerro | Cuacos de Yuste |

| Alcántara | Pasarón de la Vera | Feria | Fregenal de la Sierra |

| Azuaga | Valverde de la Vera | Hoyos | Fuente del Maestre |

| Cabezuela del Valle | Galisteo | ||

| Cáceres | Gata | ||

| Coria | Granadilla | ||

| Guadalupe | Magacela | ||

| Hervás | Robledillo de Gata | ||

| Jerez de los Caballeros | San Martín de Trevejo | ||

| Llerena | Trevejo | ||

| Mérida | |||

| Olivenza | |||

| Plasencia | |||

| Trujillo | |||

| Valencia de Alcántara | |||

| Villanueva de la Vera | |||

| Zafra |

| Hotel Sector | Non Hotel Sector | Rural Sector | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Accom-Modation | Beds | Accom-Modation | Beds | Accom-Modation | Beds | Accom-Modation | Beds |

| 1 | 153 | 7962 | 177 | 3832 | 104 | 1181 | 434 | 12,975 |

| 2 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 8 | 13 | 185 | 15 | 205 |

| 3 | 4 | 59 | 2 | 10 | 13 | 192 | 19 | 261 |

| 4 | 25 | 1264 | 26 | 967 | 68 | 617 | 119 | 2848 |

| Σ Historical Ensembles | 183 | 9297 | 206 | 4817 | 198 | 2175 | 587 | 16,289 |

| Σ HE Cáceres, Mérida, and Plasencia | 78 | 5259 | 153 | 2298 | 5 | 55 | 236 | 7612 |

| % Historical Ensembles | 40.6% | 48.3% | 60.1% | 36.2% | 24.8% | 26.0% | 36.9% | 39.8% |

| Σ Rest of Extremadura | 268 | 9971 | 137 | 8484 | 599 | 6203 | 1004 | 24,658 |

| Σ Extremadura | 451 | 19,268 | 343 | 13,301 | 797 | 8378 | 1591 | 40,947 |

| Tourist Points | Historical Ensemble | Minutes | Tourist Points | Historical Ensemble | Minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Villanueva de la Vera | Valverde de la Vera | 4 | Jarandilla de la Vera | Garganta la Olla | 26 |

| Navaconcejo | Cabezuela del Valle | 5 | Hervás | Granadilla | 27 |

| Jerte | Cabezuela del Valle | 7 | Azuaga | Llerena | 29 |

| Baños de Montemayor | Hervás | 8 | Badajoz | Olivenza | 29 |

| Jaraíz de la Vera | Cuacos de Yuste | 10 | Baños de Montemayor | Granadilla | 29 |

| Jaraíz de la Vera | Garganta la Olla | 10 | Llerena | Azuaga | 29 |

| Villanueva de la Serena | Magacela | 13 | Monesterio | Zafra | 32 |

| Jarandilla de la Vera | Cuacos de Yuste | 14 | Castuera | Magacela | 34 |

| Villafranca de los Barros | Fuente del Maestre | 14 | Monesterio | Llerena | 35 |

| Malpartida de Plasencia | Galisteo | 15 | Alburquerque | Valencia de Alcántara | 36 |

| Malpartida de Plasencia | Plasencia | 16 | Medellín | Mérida | 36 |

| Zafra | Fuente del Maestre | 16 | Torrejón el Rubio | Trujillo | 36 |

| Don Benito | Magacela | 17 | Valencia de Alcántara | Alburquerque | 36 |

| Cañamero | Guadalupe | 19 | Serradilla | Galisteo | 38 |

| Villafranca de los Barros | Zafra | 20 | Hornachos | Zafra | 39 |

| Coria | Galisteo | 21 | Mérida | Fuente del Maestre | 39 |

| Jerez de los Caballeros | Burguillos del Cerro | 21 | Alange | Fuente del Maestre | 41 |

| Almendralejo | Fuente del Maestre | 22 | Hornachos | Fuente del Maestre | 41 |

| Plasencia | Galisteo | 22 | Navaconcejo | Pasarón de la Vera | 41 |

| Fuentes de León | Fregenal de la Sierra | 23 | Serradilla | Plasencia | 41 |

| Almendralejo | Mérida | 24 | Fuentes de León | Jerez de los Caballeros | 43 |

| Alange | Mérida | 25 | Caminomorisco | Gata | 45 |

| Medellín | Magacela | 25 |

| Tourist Point | Historical Ensemble | Minutes | Tourist Point | Historical Ensemble | Minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Badajoz | Olivenza | 29 | Plasencia | Plasencia | 0 |

| Alburquerque | 44 | Galisteo | 20 | ||

| Mérida | 45 | Pasarón de la Vera | 32 | ||

| Feria | 54 | Hervás | 34 | ||

| Fuente del Maestre | 60 | Coria | 35 | ||

| Cáceres | Cáceres | 0 | Cabezuela del Valle | 38 | |

| Granadilla | 40 | ||||

| Trujillo | 48 | Cuacos de Yuste | 49 | ||

| Mérida | Mérida | 0 | Garganta la Olla | 49 | |

| Fuente del Maestre | 40 | Zafra | Zafra | 0 | |

| Zafra | 45 | Fuente del Maestre | 15 | ||

| Feria | 56 | Burguillos del Cerro | 19 | ||

| Magacela | 60 | Feria | 19 | ||

| Trujillo | Trujillo | 0 | Llerena | 38 | |

| Cáceres | 48 | Fregenal de la Sierra | 39 | ||

| Magacela | 58 | Jerez de los Caballeros | 39 | ||

| Mérida | 45 |

| Tourist Point | Historical Ensemble | Min. | Tourist Point | Historical Ensemble | Min. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alange | Mérida | 26 | Jerez de los Caballeros | Jerez de los Caballeros | 0 |

| Fuente del Maestre | 42 | Burguillos del Cerro | 21 | ||

| Zafra | 48 | Fregenal de la Sierra | 21 | ||

| Magacela | 57 | Zafra | 39 | ||

| Feria | 58 | Feria | 42 | ||

| Almendralejo | Fuente del Maestre | 23 | Fuente del Maestre | 52 | |

| Mérida | 23 | Olivenza | 59 | ||

| Zafra | 29 | Jerte | Cabezuela del Valle | 6 | |

| Feria | 35 | Plasencia | 45 | ||

| Burguillos del Cerro | 47 | Hervás | 52 | ||

| Llerena | 54 | Pasarón de la Vera | 56 | ||

| Baños de Mont. | Hervás | 8 | Galisteo | 60 | |

| Granadilla | 29 | Malpartida de Plasencia | Galisteo | 14 | |

| Plasencia | 37 | Plasencia | 16 | ||

| Galisteo | 39 | Pasarón de la Vera | 25 | ||

| Caminomorisco | Gata | 44 | Coria | 30 | |

| Granadilla | 46 | Hervás | 35 | ||

| Trevejo | 47 | Cuacos de Yuste | 41 | ||

| Hoyos | 48 | Granadilla | 41 | ||

| Hervás | 50 | Cabezuela del Valle | 46 | ||

| Plasencia | 50 | Garganta la Olla | 55 | ||

| Robledillo de Gata | 51 | Hoyos | 57 | ||

| Coria | 53 | Monesterio | Zafra | 32 | |

| Don Benito | Magacela | 16 | Llerena | 36 | |

| Mérida | 45 | Fuente del Maestre | 44 | ||

| Trujillo | 47 | Fregenal de la Sierra | 45 | ||

| Guadalupe | Guadalupe | 0 | Burguillos del Cerro | 50 | |

| Hervás | Hervás | 0 | Feria | 51 | |

| Granadilla | 27 | Navaconcejo | Cabezuela del Valle | 5 | |

| Plasencia | 34 | Plasencia | 35 | ||

| Galisteo | 37 | Pasarón de la Vera | 41 | ||

| Coria | 53 | Galisteo | 50 | ||

| Cabezuela del Valle | 54 | Garganta la Olla | 54 | ||

| Pasarón de la Vera | 60 | Hervás | 57 | ||

| Jarandilla de la Vera | Cuacos de Yuste | 14 | Cuacos de Yuste | 58 | |

| Valverde de la Vera | 22 | Olivenza | Olivenza | 0 | |

| Garganta la Olla | 26 | Feria | 55 | ||

| Villanueva de la Vera | 26 | Jerez de los Caballeros | 59 | ||

| Pasarón de la Vera | 34 | Torrejón el Rubio | Trujillo | 36 | |

| Plasencia | 60 | Galisteo | 52 | ||

| Plasencia | 54 | ||||

| Valencia de Alc. | Valencia de Alcántara | 0 | |||

| Alburquerque | 37 | ||||

| Alcántara | 55 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Gurría-Gascón, J.-L.; García-Berzosa, M.-J. The Cultural Heritage and the Shaping of Tourist Itineraries in Rural Areas: The Case of Historical Ensembles of Extremadura, Spain. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9040200

Sánchez-Martín J-M, Gurría-Gascón J-L, García-Berzosa M-J. The Cultural Heritage and the Shaping of Tourist Itineraries in Rural Areas: The Case of Historical Ensembles of Extremadura, Spain. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2020; 9(4):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9040200

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Martín, José-Manuel, José-Luis Gurría-Gascón, and María-José García-Berzosa. 2020. "The Cultural Heritage and the Shaping of Tourist Itineraries in Rural Areas: The Case of Historical Ensembles of Extremadura, Spain" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 9, no. 4: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9040200

APA StyleSánchez-Martín, J.-M., Gurría-Gascón, J.-L., & García-Berzosa, M.-J. (2020). The Cultural Heritage and the Shaping of Tourist Itineraries in Rural Areas: The Case of Historical Ensembles of Extremadura, Spain. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(4), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9040200