1. Introduction

Online reputation is a concept which has arisen as a result of the continuous advances in information and communications technology during the 21st century. This progress includes the setting up of Web 2.0 which allows the interconnection between users by means of the use of the network, generating new communicative realities [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Given the possibilities of the Internet, we are witnessing a gradual increase in their use by users, as is shown in the latest report on the General Framework of Means. It reveals that the use of the Internet has increased from 5 min per user at the beginning of the 21st century to 139 in 2018 [

5]. With this scenario, a multitude of web portals and social networks have arisen, the main objective of which is to facilitate this interconnection between users as is the case with Facebook, Google, and Tripadvisor. The increase in the use of the network, together with the possibility of interaction between users in this new communicative situation, has created the current situation of a huge amount of information on the Internet available to the final consumer.

Online reputation corresponds to the new communicative reality. Numerous authors define it as a set of positive and negative opinions which are recorded on the Internet by the end user by means of the use of various online platforms. They affect various sectors including tourism [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The changes recorded in this field emphasise the new profile of tourists, which, in many cases, are defined as 2.0 tourists [

12,

13]. Tourists of this type are characterised by the large amount of information they have on destinations and accommodation; at the same time, they are responsible for the online reputation of each of them.

The 2.0 tourist records his personal experiences on a large number of online platforms. He generates essential information which the future traveller can consult to plan his trip [

14]. The proliferation of this information has had a significant effect on the processes of planning travel, on reservations for accommodation, and also on the acquiring of tourist products. These activities, which were formerly carried out by traditional means of communication, are currently conducted on the Internet [

15]. The latest annual report of FRONTUR and EGATUR [

16], which was published in 2012, reveals the importance of the acquiring of tourist products and the administration of travel on the Internet. Among the data given by these reports, it can be pointed out that around 65% of the international tourists who arrived in Spain in 2012 had planned their trip on the Internet. This trend can also be observed in Spanish tourists, with the Region of Valencia leading the way as 75% of the tourists from this region used the Internet.

The tourism activities being offered need to adapt to the new scenario. Indeed, in Spain, companies connected with the tourist sector are those which have implemented more ITC in recent years [

17]. The 2018 E-SME report [

17] maintains that 94.1% of accommodation companies have computer equipment and over 92% have an Internet connection; it also stresses the strong presence of websites of their own (95.1%) and social networks (87.2%), this last figure being considerably higher than the national average for other sectors (49.6%).

The emergence of online reputation has caused a considerable increase in the competition between destinations and accommodation and is a new parameter to be taken into account by the managers of tourist businesses. This reputation feeds on the opinions expressed by tourists on the Internet of various services. The Rural Tourism Observatory [

18] has identified as being relevant the location, value for money, customer service, comfort, and cleanliness. These experiences have a considerable effect on the choice of the final destination by the future tourist and are currently essential for the management of tourist accommodation [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Therefore, those with a positive online reputation can increase their prices and maintain their occupation level, while a negative reputation may lead to a drop in the number of tourists [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

The repercussions of online reputation in the tourist sector have given rise to an extensive bibliography in which two lines of research stand out:

- -

On the one hand, we find studies on demand orientated towards the influence of online reputation in the perception of the future tourist and how this has affected the planning of the trip, and also on the confidence travellers have in the opinions [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

- -

On the other hand, from the point of view of the supply there are two main lines of research. Numerous authors have analysed online reputation regarding specific destinations and how it affects their occupation levels. Others approach the management of both the public administrations and the managers of the tourist accommodation in the face of the recording of these opinions [

23,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

Most of the studies carried out have concentrated on hotel type accommodation by resorting to the use of statistical techniques which avoid the territorial nature of tourism. In this sense, this study expounds two differentiating characteristics regarding a large proportion of the current literature. The first is the analysis of the online reputation of rural accommodation and the second is the use of spatial statistics.

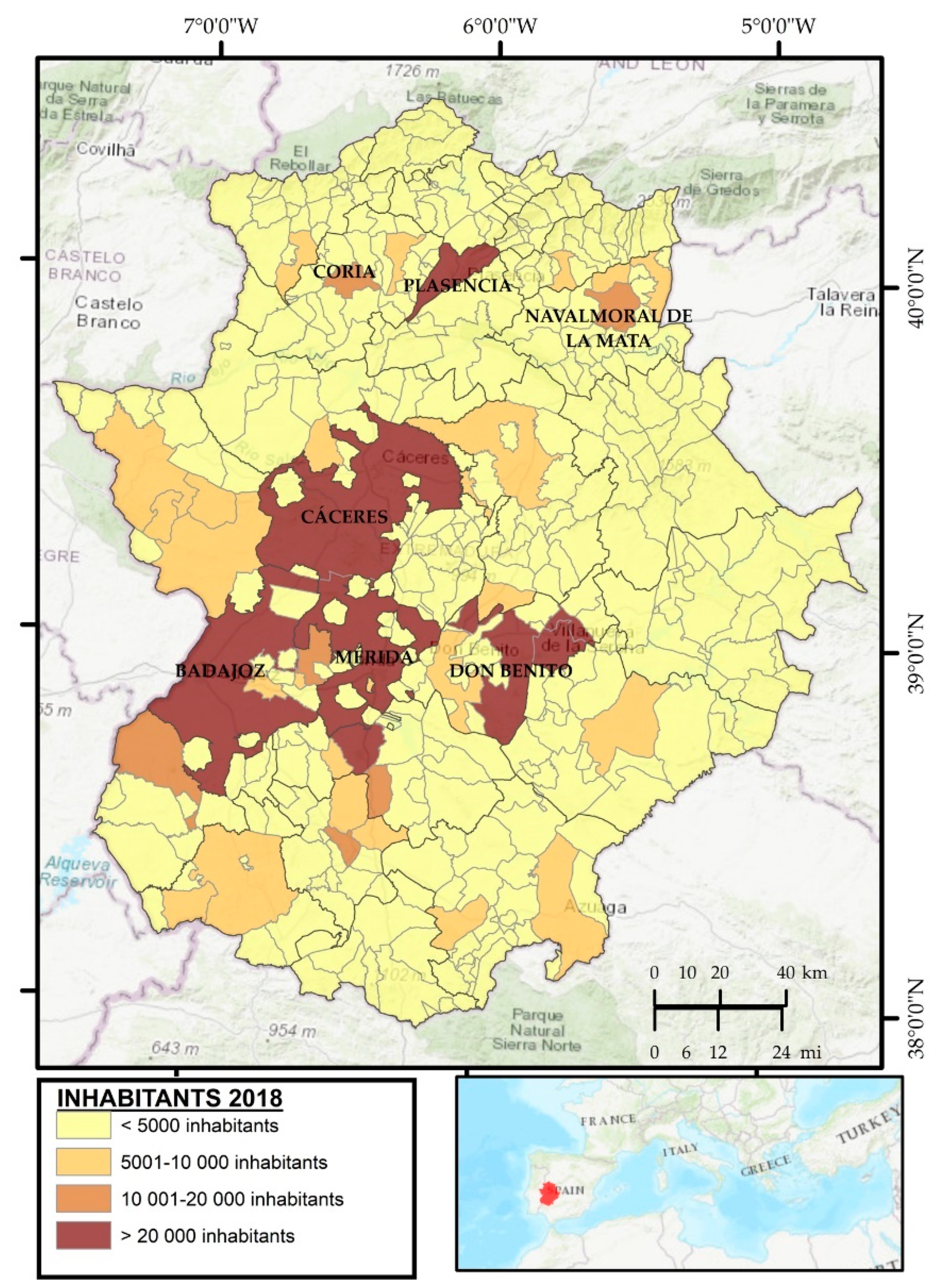

Given this scenario, the main objective of this study was to get to know the situation of online reputation and determine whether concentrations of negative or positive mentions exist in the rural accommodation establishments located in Extremadura by means of the analysis of a series of aspects making up this parameter. In order to do so, we took as a reference those which the Rural Tourism Observatory in its report “What the rural tourist most values” [

18] identifies as variables which affect the decision as to the final destination, together with those aspects most valued by a rural tourist during his stay. These include value for money, food and drink services, cleanliness, comfort, customer attention, and location. As a complement, we decided to include the variables referring to the general assessment made by the tourist of hotel type accommodation and that mentioning the overall opinion of the room service as these are the parameters which have obtained the largest number of references during the study period. In order to achieve this objective, we resorted to the use of spatial statistical techniques which aim to clarify the overall situation for accommodation as a whole and moreover that characterising each territory. Given the wide diversity of geostatistic techniques, we decided to use several, one global (the Global Getis-Ord) and another local (the Gi* Getis-Ord). The results of the latter were compared with those obtained by means of Kernel Density which measures the spatial distribution of variables. The aim of this was to validate that Hot Spot Analysis is an excellent tool for adding territorial perspective to numerical perspective. The achieving of both objectives would allow the Administration and the owners to take measures leading to the improvement of their reputation when this is necessary.

3. Results

Online reputation is a key aspect in the selection of a destination or accommodation. As a result it is necessary to analyse the factors identified by the Rural Tourism Observatory. These include those which influence the decision on accommodation and the most highly valued during the trip by the rural tourist. Moreover, the analysis of two other parameters has been included, the general assessment carried out on accommodation and that recorded on the room, as both items are very frequently commented on by tourists.

3.1. Factors Which Influence the Decision on the Final Accommodation

One of the parameters which most influence the decision on the final accommodation of the rural tourist is the service provided regarding food and drinks. Indeed this is one of the items which has accounted for the largest number of mentions during the study period. In total, 7231 mentions of this service were recorded, of which 82.6% were positive and 17.4% negative. These data prove the very good reputation of these services offered by rural tourism accommodation. However, it is interesting to get to know their distribution in the territory and to find out whether there are differences between subsets of the sample. The G Getis Ord test (

Table 4) includes differences between the positive and negative mentions. In general terms, the positive mentions tend to be distributed in high value clusters and to present a positive spatial autocorrelation; in contrast, negative mentions follow a random distribution pattern.

The territorial distribution of the local index (

Figure 4) reveals two types of groupings in the positive opinions, with a statistical significance of 95% and 99%. The district of La Vera is the only one with aggregates of high positive values in the food and drinks service. In Miajadas-Trujillo, the Sierra de Gata, the Campo Arañuelo, Villuercas-Ibores-Jara, and La Serena these aggregates accumulate low values of positive mentions. The negative mentions are distributed over the territory at random. Indeed, only small clusters were detected in the districts of the Valle del Jerte and Villuercas-Ibores-Jara, albeit with a level of statistical confidence of 90%. The concentration of this kind of mentions in the district of Las Villuercas, together with the existence of clusters of low values of positive mentions, shows the poor reputation of these services. For this reason, the managers of the accommodation establishments involved must take action to improve them.

The cartography represents the results obtained from the application of the Kernel density method, highlighting the considerable differences between this technique and those of spatial statistics. They occur owing to the fact that the Kernel density interpolation method does not take into account proximity criteria. This situation generates points of high densities in the case of both positive and negative mentions in the northwest areas of Cáceres province where there are a greater number of opinions. Moreover, the application of this analytical technique identifies some areas of high densities of both negative and positive mentions in places in which the Gi* index shows areas with no statistical significance (

Figure 4).

The opinions on value for money amount to 1477, of which 73.6% are positive and 26.4% negative. In general terms, it can be observed that this aspect has a worse reputation among tourists. The analysis of spatial patterns (

Table 5) shows the distribution of the values of this parameter over the region of Extremadura. It reflects that the positive mentions follow a random distribution pattern while negative mentions are grouped together.

A detailed territorial analysis reflects considerable differences in both opinions. The positive mentions are concentrated in two types of spatial aggregates: high and low values. The district of La Vera shows high values with a statistical significance of between 99% and 90% of confidence. Spatial aggregations of low values of positive mentions are also found in the areas of the Valle del Jerte, Valle del Ambroz, Sierra de San Pedro-Tajo Internacional, and Villuercas-Ibores-Jara. On the other hand, the district of Miajadas Trujillo presents clusters of low positive mentions in the northern area while in the southern part, the reverse is true.

Negative opinions have a low level of grouping; aggregates of high values only occur in the districts of the Sierra de San Pedro-Tajo Internacional and Villuercas-Ibores-Jara. In this scenario, the competitive advantage of the district of La Vera compared with the remainder of the territories can be appreciated, as it is the only one which shows aggregates of high values of positive opinions on the value for money of their rural accommodation establishments. In contrast the area of Villuercas-Ibores-Jara and the Sierra de San Pedro-Tajo Internacional represent the areas with the highest accumulation of negative mentions.

The Kernel density method (

Figure 5) identifies numerous areas of high densities of positive and negative mentions which coincide with areas without statistical significance after the application of the Getis Ord local indicator.

Customer attention accounted for 3800 mentions, of which over 95% were positive. These data prove the good reputation of rural accommodation establishments of Extremadura on this point. Its territorial distribution shows certain differences according to the data obtained after the application of the Getis Ord global index, in which the positive mentions show a positive spatial autocorrelation in clusters of high values, while negative mentions follow a random pattern (

Table 6).

Figure 6 represents the aggregations which occur in the case of positive and negative mentions. It shows two well differentiated types of aggregates: those corresponding to the agglomeration of high values and those of low values. In this sense the districts of the Valle del Jerte and La Vera stand out for their positive online reputation on customer attention with a statistical significance of between 90% and 95%. In the opposite situation are the districts of Monfragüe, Sierra de Gata, Campo Arañuelo, Villuercas-Ibores-Jara, Miajadas-Trujillo, La Serena, and Olivenza where the agglomerations correspond to a low number of positive mentions. However, an analysis of the negative opinions reveals that only high value aggregates exist. This reflects a complex situation in the districts involved and the need for action to change the situation.

In both parameters the Kernel density method identifies areas of high densities with points which the Getis Ord local index classifies as areas of hotspots. However, in other districts which appear as points without statistical significance, this technique classifies them as areas of high densities of positive or negative mentions.

3.2. Factors Most Valued by the Rural Tourist

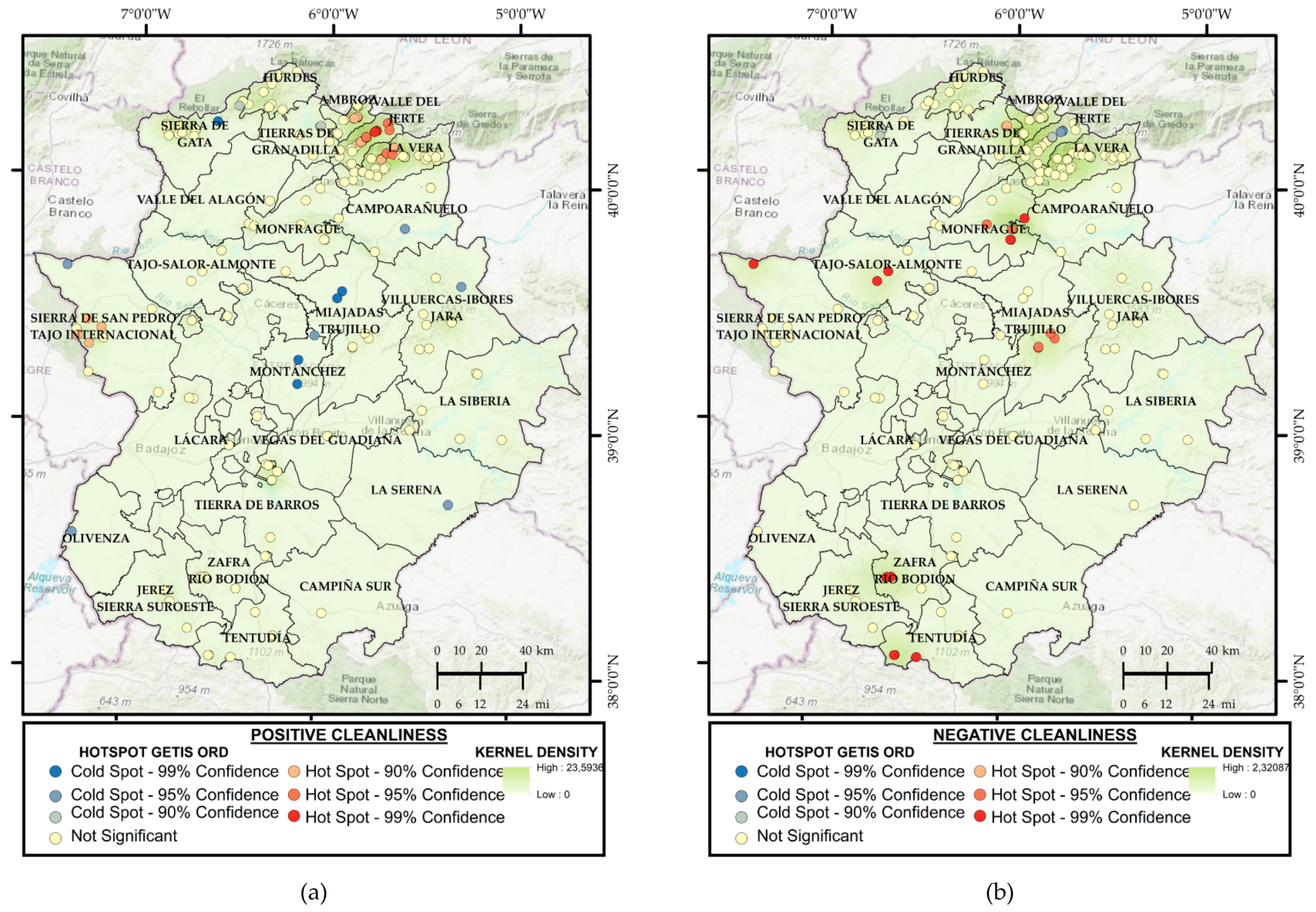

Cleanliness is mentioned 2356 times, of which 83.15% are positive and 16.85% negative to show a very good online reputation. They present different patterns of distribution (

Table 7). The positive mentions shape aggregates of high values with a positive spatial autocorrelation and the negative mentions follow a random pattern.

The territorial distribution of the Gi* index takes the form of a cluster of high and low values in the case of negative and positive mentions (

Figure 7). On the one hand, the largest number of positive opinions is concentrated in the northeast of the province of Cáceres, to be precise in the districts of La Vera, the Valle del Jerte, and the Valle del Ambroz. The situation is the opposite in the areas of the Sierra de Gata, Campo Arañuelo, Miajadas-Trujillo, Villuercas-Ibores-Jara, Montánchez, and La Serena. Clusters of high values can also be observed in the district of the Sierra de San Pedro-Tajo Internacional and of low values in the northern part of this area. Among the negative opinions the area of the Valle del Jerte stands out positively as it shows a cluster of low values as is the case in the Sierra de Gata. Likewise, there are districts where negative opinions are abundant such as the Tierras de Granadilla, Monfragüe, Tajo-Salor Almonte, the Sierra de San Pedro-Tajo Internacional, Miajadas-Trujillo, Zafra, River Bodión, and Tentudía. Some also have low values of positive opinions. This scenario reveals the excellent reputation of the northeast of the province of Cáceres.

The application of the Kernel density interpolation method identifies areas of high densities which coincide with areas without statistical significance in the results obtained from the Getis Ord local index.

Comfort and relaxation are mentioned on 2350 occasions, of which 75.6% are positive and 24.4% negative. Although the total number of mentions recorded on this parameter is similar to those obtained in the cleanliness variable; there are more negative opinions. For this reason it can be concluded that this aspect has a worse reputation. The analysis of spatial patterns reflects that the positive mentions show a positive spatial autocorrelation. It forms clusters of positive values, while the negative mentions are distributed at random (

Table 8).

The territorial distribution of Gi* in the positive and negative opinions with a statistical significance which varies between 90% and 95% reflects a complex situation (

Figure 8). The districts in the northeast of the region of Extremadura show a concentration of high levels of positive mentions. Moreover, aggregates of low values of positive mentions are distributed in the Sierra de Gata, Miajadas-Trujillo, Campo Arañuelo, Tajo-Salor-Almonte, Villuercas-Ibores-Jara, La Siberia, and La Serena. Some of these territories coincide with aggregates of numerous negative mentions. This scenario is detected in the districts of Campo Arañuelo, Villuercas Ibores-Jara, and La Siberia. These areas are joined by the district of Tentudía, in which these clusters show a level of statistical significance of 99%. On the contrary, the Sierra de San Pedro-Tajo Internacional presents low values of negative mentions.

The Kernel density method gathers insignificant groupings for the Gi* index.

The landscape and the surroundings are important for the rural tourist. 3683 opinions were gathered on the subject, of which 95% are positive. This shows the excellent assessment of the landscape of Extremadura. The analysis of spatial patterns (

Table 9) reveals the presence of spatial autocorrelation in the case of positive mentions, which are characterised by forming clusters of high values. However, negative mentions are distributed at random.

Despite the excellent general reputation, there are areas in which the number of positive mentions is low: these areas are identified by the Getis Ord local index as cold spots of positive opinions (

Figure 9). This is the case of the districts of Campo Arañuelo, Villuercas-Ibores-Jara, Miajadas-Trujillo, Sierra de San Pedro Tajo-Internacional, Montánchez, and La Serena. However, these areas do not appear as aggregates of high values of negative mentions; this scenario appears in the districts of Tajo-Salor Almonte and La Siberia. All this generates a negative online reputation of this aspect in these areas.

Although the Kernel density interpolation model does not identify key points in the zoning of this variable in the case of positive mentions, it does do so in the negative ones where they coincide with areas of high densities and the cluster of this type of opinions in the districts of Tajo-Salor-Almonte and La Siberia.

3.3. Other Variables

Rural accommodation is a relevant aspect of online reputation. The number of opinions recorded amounts to 8464. Of these 91.58% were positive, which reflects the high level of satisfaction of the tourist in general with all the services provided by rural accommodation establishments in the region of Extremadura, despite the fact that this situation varies in some more specific services (food and drinks, cleanliness, etc.).

The pattern analysis (

Table 10) reflects groupings in the case of positive opinions and randomness in that of negative ones.

The territorial distribution of Gi* (

Figure 10) shows how positive opinions are grouped in clusters of high values in the district of La Vera. However, in the areas of Campo Arañuelo, Miajadas-Trujillo, Villuercas-Ibores-Jara, and La Serena the agglomerations are due to the presence of low values of positive mentions. At the same time the presence of these agglomerations of high values of negative mentions in the areas of Monfragüe and Tajo-Salor-Almonte should be mentioned.

The results obtained after the application of the Kernel density method do not coincide with those expounded after the values deriving from the Getis Ord local index, which corroborates the differences after the application of both techniques of spatial analysis.

The condition of the rooms and the room service account for 5317 opinions, of which; 28% are negative. The analysis of spatial patterns (

Table 11) shows positive spatial autocorrelation in both types of opinions in such a way that these tend to take the form of clusters of high values.

Although the global assessment reflects the existence of a large number of negative mentions, it is interesting to find out the casuistry of each district (

Figure 11). It can be observed that there are cold spots and hotspots in the specific case of positive mentions, while in the negative mentions only agglomerates of high values appear to reflect the poor reputation of some districts. La Vera is the only area which concentrates high values of positive mentions. At the same time, some of these districts in which the existence of cold spots with regard to positive opinions stands out are represented as ensembles in which high values of negative sentences predominate, as occurs in the area of the Valle del Ambroz and the Sierra de San Pedro-Tajo Internacional, together with the district of Monfragüe.

The results obtained by the geostatistical analysis by means of Gi* Getis-Ord reveal an interesting territorial situation which is repeated in the items analysed. This is the good online reputation of the establishments located in three districts which are very significant from the perspective of tourism: La Vera, the Valle del Jerte, and the Valle del Ambroz. In these territories very positive comments are detected and in a high percentage of demand in most of the aspects analysed. However, this fact contrasts with the low percentages of positive mentions obtained in other districts located in the north of Extremadura or in areas which aim to encourage the development of their rural tourism. This can be observed in a large proportion of the districts of Villuercas-Ibores-Jara and the peneplain of Trujillo. In addition it is also noteworthy that in a large proportion of the territory insignificant values appear; this means that there is no clear tendency towards defining them as cold spots or hotspots.

4. Discussion

The online reputation of destinations and of all their elements has a considerable effect on their competitiveness [

62,

63] as is mentioned in numerous studies. It has become a tool for creating an image of any destination, especially at a time such as the present when smart destinations prevail [

64,

65]. This is the case to such an extent that some studies link the online reputation to the very profitability of the accommodation establishment [

66].

The case analysed shows that it is possible to perform an analysis of online reputation taking into account its territorial distribution, as opinions can be added as a spatial attribute. In this sense it is clear that the comments made by tourists on the destination or any tourist element may be positive or negative, which means that it may be considered whether there is a certain tendency towards a concentration of the former or the latter. Because of this there is clearly a need for an analysis of the comments made by tourists.

The importance of an online reputation in which positive comments on the supply of accommodation predominate has a direct effect on the image of the destination as a whole. It should not be forgotten that accommodation is considered to be a key aspect in the analysis of the tourist experience. As a consequence of this, the importance of comments on accommodation has been dealt with in the literature over the last decade. However, there has been a clear increase in the number of these mentions in recent years. These studies analysed online reputation and its impact [

67] on numerous accommodation types such as Airbnb [

68] and hotels [

69] in very different environments [

70].

Rural accommodation is included in this trend and its online reputation has been examined from various perspectives designed to improve the marketing strategies [

71,

72]. However, a geostatistical analysis is performed in very few cases [

58]. As a result, although it is true that there are many studies on the online reputation of accommodation establishments, analyses in which the territory plays a key role such as geostatistical ones are not normally carried out. In this sense and given this shortcoming of the literature, we resorted to an analysis which aims to detect similar behaviour patterns in nearby environments.

After its application, it is corroborated that most of the comments recorded in each of the study variables are positive in nature and that few of the mentions are negative. This scenario is reproduced in other places owing to the empathy which the tourist feels for the manager of these accommodation establishments owing to the new interaction which is possible through the development of the 2.0 web [

73].

Although, in general, positive comments tend to predominate, negative ones also exist. This duality should act as a basis for introducing corrective measures or putting forward proposals for improvements. These will be designed to continue with the development and the maintenance of those aspects which have been valued positively and to create specific plans for improvement when the opposite is true. In this sense it is an advantage that the general index created by Getis-Ord allows this type of interpretation referring to the concentration or the randomness of the distribution of certain opinions. However, any action designed to improve the online reputation of destinations will be a general policy which is poorly adapted to the situation of the area. Proof of this is that when a local analysis such as the Gi* Getis-Ord is used the perspective obtained is adapted to each territory, each establishment, or each destination. It can readily be inferred from this that the action which may be taken will be more suitable for specific cases. Moreover, given that the neighbourhood criterion is considered, it will be possible to design policies common to nearby territories, especially if as is the case very clear proximity patterns have been detected. This aspect goes unnoticed when Kernel density is used.

The results obtained stress that some parameters accumulate numerous negative mentions (over 20%). This is a clear sign that both the Administration and the owners must change their strategies. In the particular case of Extremadura it can be appreciated that this situation affects key aspects in the selection of a destination. These include the room, value for money, and comfort. These data are genuine weak points of the online reputation of the area analysed, although there are considerable differences between tourist districts which allow the determination of the application of geostatistics to those places in which there are aggregates of high values of negative mentions for each of these variables. In this sense it can be observed how the districts of Campo-Arañuelo, Villuercas-Ibores-Jara, La Siberia, and Tentudía have the worst scores for comfort and relaxation, with the application of the Getis-Ord local index reflecting the existence of aggregates of high values of negative mentions. As far as value for money is concerned, the districts of Villuercas-Ibores-Jara and the Sierra de San Pedro-Tajo Internacional stand out; as a result these areas need specific action.

Given that online reputation is a key aspect when it comes to taking the decision to travel [

14,

15], it is necessary to take great care with this aspect and to encourage the owners to take steps to remedy the situation. If the current situation continues this could lead to a clear loss of competitiveness as value for money and the comfort of the establishment are essential parameters for a tourist [

18].

The satisfactory management of these mentions may lead to a reduction in the number of negative comments on these aspects [

37,

38,

53]. Despite this, some studies point out that the management of this reputation in rural accommodation establishments is very infrequent, owing to which this accumulation of negative mentions in certain districts may considerably reduce the reception of the number of tourists [

58].

At a technical level, the results reveal that geostatistics is a useful tool for analysing online reputation, above all because if we resort to the proximity criterion it facilitates the setting in motion of initiatives of improvement so as to see a return on the investment which may be made by the Administración. In this case, it is confirmed that the application of spatial statistical techniques has allowed the specifying of which places stand out for having a positive or negative online reputation for each of the aspects which have been featured in this study. At the same time, their effectiveness has been shown in the analysis of spatial patterns with regard to the use of other techniques such as the Kernel density interpolation method [

58].

Despite the fact that the results obtained by means of the application of geostatistical techniques are interesting, the use of these tools is not without its problems. These do not lie in the techniques, which are very solid and have been adopted by numerous researchers analysing varied themes [

74,

75,

76,

77], but in their configuration. The main problems include in particular the need to choose a conceptualization of spatial relationships by means of various alternatives: inverse distance, inverse distance squared, fixed distance band, or zone of indifference. Naturally the consideration of one type of spatial relationship or another implies the obtaining of results showing slight differences, owing to which it is necessary to carry out numerous tests and compare them in order to make the best decision. In the case which concerns us, taking into account the territorial distribution of the sample it was considered appropriate to resort to a fixed distance so as to ensure the presence of at least 1 neighbouring accommodation establishment. This condition was met in a Euclidian distance of 12 km (7.46 miles). Nevertheless, it may be considered that depending on the distribution of the object under analysis it is possible that another method of conceptualising the most suitable spatial relationship may exist. There is no doubt that this is a possible limitation, although given that substantial changes are not appreciated in the results it is understood that using a Euclidian distance of 12 km is the most appropriate course of action. The decision to choose one type of spatial relationship or another is not decisive in the case analysed, although it can be pointed out that in other cases it may be vital. This means that it is recommendable to use several types of spatial relationship and to compare the results, in such a way that the models which are most similar to each other are chosen [

25,

50,

52].

Another limitation of the techniques is that of the method used to consider distance as there are two possibilities: Euclidean distance and Manhattan distance, although it is not possible to use real distance or strictly speaking travel time obtained by means of correct impedance. This limitation is important, although for the moment the bibliography used has not found a solution to the problem. Despite this disadvantage, it should be pointed out that the studies consulted tend to use the Euclidian distance.

Although these are the main limitations at a technical or instrumental level, others linked to the information analysed itself also exist. Among them the need for using numerical and therefore quantitative criteria stands out and moreover the reliability of the data themselves. It is obvious that in order to carry out statistical operations it is necessary to use numbers, although when the online reputation of an accommodation establishment or a destination is analysed it is possible to use qualitative characteristics as has been revealed in some studies [

78,

79]. This stresses that these techniques are incompatible with qualitative data, which are sometimes very important when parameters such as online reputation are analysed. Furthermore, the study of online reputation is not without controversy as some studies indicate that false opinions of the accommodation establishments are disseminated [

80,

81]. As a consequence of this uncertainty on the veracity of the comments, studies have arisen to measure the factors which may affect credibility [

80] or how to face the criticisms received [

82].

Taking into account the aspects mentioned, it is stressed that the use of analytical techniques such as the Gi* Getis-Ord allows the detecting of interesting distribution patterns in online reputation, to which can be applied if appropriate tourism policies designed to eliminate imbalances and to encourage marketing techniques suitable for each space. However, the use of the same implies of necessity resorting to numerical and therefore non qualitative parameters. Despite this, if one wishes to use this type of techniques, if qualitative information is available it is possible to transform it into quantitative information. Nevertheless, it should not be forgotten that part of the literature chooses qualitative techniques.

Despite the advantages and disadvantages of the use of geostatistical techniques for analysing online reputation, it must be acknowledged that their applicability is interesting. This takes the form of designing specific formative campaigns for the most problematical areas, which is also interesting if it is taken into account that the situation of each rural accommodation establishment analysed is known.

In the opinion of the authors, given the good results obtained at an instrumental level, the continuation of the research will affect precisely the analysis of the negative opinions, although in this case, the contrasting of the opinions of the demand with those of the supply involved will be proposed. In this way, the vision and the possibilities of the improved competitiveness offered by online reputation would be completed.