Abstract

Counterfeiting has always been a concern, costing a significant amount of money and causing losses in international trading markets. Radio frequency identification (RFID) tag Anti-counterfeiting is a conceptual solution that has received attention in the past few years. In this article, we present a survey study on the research topic of anti-counterfeiting products using RFID tags on merchandise. As this issue evolved in industry, there were several techniques used to address the problem; each technique uses a different concept and mechanism in resolving the issue. Each technique also has different pros and cons which we will address at the end of this paper with our findings. As we explore RFID technology and its implementation, we will discuss previous research before proceeding to the core of the topic of RFID Anti-counterfeiting based on the methods used. We compare the different techniques used at the end of the paper.

1. Introduction

Since counterfeiting is a significant problem affecting merchandise and retail systems worldwide, any anti-counterfeiting system needs to be built on a secure authentication protocol. It is estimated that the counterfeiting industry has cost U.S. manufacturers over $200 billion over the past two decades [1,2] and contributed to significant losses for goods manufacturers through the sale of counterfeit products. The issue has severely impacted industry growth and many researchers have adopted RFID technology instead of the traditional bar-code to address the counterfeiting problem, although a secure and comprehensive solution has yet to be achieved. In addition to product counterfeiting, there is the possibility of cloning RFID tags attached to the products. Radio frequency identification (RFID) and wireless sensor networks (WSN) are two important wireless technologies that have a wide variety of applications and provide limitless future potentials, while RFID tags are similar to actuator which requires a control signal and a source of energy. Product counterfeiting has led to significant losses for the global retail market. Although researchers have tried to address this issue, there remains a huge gap in the literature when it comes to surveying the problem based on the technique which was used to prevent or minimize the tag anti-counterfeiting. In the next section, we will briefly discuss RFID implementation in industry to give a background understanding of RFID use in general, before conducting a review of the literature in sections three and four. We will outline and provide an overview of the research topic, technology and methods used, after a brief introduction of RFID technology identifying some of the RFID properties that make it a suitable technology for retail and supply-chain industries. We also outline security and privacy issues which occur with the use of RFID technology. The core contribution of this research paper will be in providing a detailed study of the methods used to address the counterfeiting issue in products using RFID tags, as well as the technologies that these methods employ. We conclude with a comparison of these methods based on classification, taking into account certain technology aspects to provide a comprehensive overview of the methods used so far to prevent product counterfeiting.

2. RFID Technology and Some Implementations

2.1. RFID Technology

RFID systems consist, in general, of three components: a tag, which is attached to an object; a reader; and a database. The tag communicates with the receiver using radio frequency signals. Some tags are powered with a power source, while some are not, relying on the power they receive from the reader. The tag consists of an antenna, memory chip and sometimes a power source as mentioned. There are other types of tags, chipless tags, that do not use memory chips; we will mention them later in the next section. Usually the reader will send a signal to the tag to obtain its information, which will relay with its tag ID, then compare it with its records in the database. As the author in [3] suggested, that the life cycle of the RFID system should pass through five phases, Phase 1–Initiation, Phase 2–Acquisition/Development, Phase 3–Implementation, Phase 4–Operations/Maintenance and Phase 5–Disposition. There are many different implementations of RFID technology in industry. We begin by providing a brief description of some of these implementations before advancing to the issue of counterfeiting and cloning of RFID tags.

2.2. Some Implementations of RFID Technology in Industry

The RFID technology is used widely in supply chain (SC), pharmaceutical industry, food industry, retailer systems, education and libraries and many more. RFID technology is used widely in supply chain (SC), the pharmaceutical industry, food industry, retailer systems, education, libraries and many more areas. The technology was used widely in education by issuing cards for students or teachers to give them privileges to lab equipment, tools and the use of other ICT (information communication technology) resources in labs [4]; the issue of counterfeiting did not present a threat in this industry. The reason for this lack of threat is that this industry is not attractive to the attackers as it has no feasible financial benefit to them. The same reasoning applies for the use of RFID tags in libraries [5]. The implementation of RFID technology in SCM (supply chain management) and retail systems is a different story, as the issue of counterfeiting had evolved in this industry and caused serious threats and losses. In [6], the authors explore and examine the role of RFID technology in the area of SCM. Extensive research has been carried out considering the adoption of RFID technology in the Greek environment. Case studies have also been analysed to point out the industries and/or organizations that have adopted RFID technology. A key recommendation has forced companies to undertake a pilot implementation or pilot project to assess return on investment (RoI) before full RFID deployment, with a preferred approach being to restrict the pilot implementation to a portion of the company only; however, the authors do not provide any guidelines or recommendations on effective pilot implementation or discuss the issue of counterfeiting or anti-counterfeiting measures. The same issue is found in [7], where the authors present a historical view of the effects of the RFID technology, providing useful information to managers planning an RFID-enabled SCM project. The first tier of an RFID-enabled SCM project is the rush to comply with the terms that may result in the hasty implementation of RFID. The second tier is the integration of RFID into existing systems, after meeting the mandates, and the third tier is the formation of new operating processes as a result of the integration. The authors discussed the barriers affecting the RFID industry; such as, standards, cost and reliability but do not discuss tag cloning and counterfeiting. In [8], the authors exploit a phase fingerprint which extracted phase value of the back-scattered signal provided by the COTS RFID readers. The authors also implemented a prototype of TagPrint using COTS RFID devices and tested the system with over 6000 tags; they showed that the new system fingerprint exhibits a good fitness of uniform distribution and the system achieves a surprising Equal Error Rate of 0.1 percent for anti-counterfeiting. In [9], the authors present the pros and cons of using radio-frequency identification (RFID) in supply chain management. The study states and explains some of the pros of the using an RFID system in SCM, such as non-line-of-sight (NLOS) and automatic NLOS scanning, labour reduction, asset tracking and returnable items, improved inventory management, ability to withstand harsh environments, and cost savings. Additionally, the authors address some of the cons of RFID use in SCMs, such as deployment issues, manufacturing sector concerns, lack of standards, privacy concerns, and interference and reading considerations. The work offers a detailed treatment of each of these factors, but without covering the counterfeiting issue. In [10], the authors proposed a software framework to integrate both RFID and WSNs into SCM systems by establishing a communication channel between the electronic product code information service or EPCIS for RFIDs and mediation layer (MDI) for WSNs. While the RFID focus is on the identification of the objects, the WSN will monitor the control of the supply chain environment. Further, they address the problems associated with this approach of integration, such as disjointed networks between RFID and WSNs, and their different objectives and capabilities for each industry. The authors describe the EPCIS as a particular web service interacting with the whole RFID system and working as a gateway between any requester of tag info and the database. The authors also explain a case which describes their approach, but still did not mention the security and privacy issue in such a framework, including anti-counterfeiting measures, which we strongly recommend.

3. RFID Anti-Counterfeiting Methods and Technologies

RFID tag counterfeiting can be defined as creating a replica of a tag by either replicating the hardware component of a tag or by copying its software in such a way that the genuine reader, database or users would not know the difference between the actual tag and the replicated one. In general, we can categorise anti-counterfeiting techniques used in the products using RFID systems based on the method or the technique which they adopt, giving four major classifications:

- PUF Based ‘Unclonable’ RFID ICs and chipless RFID tags for anti-counterfeiting: Since PUF-based ‘Unclonable’ RFID ICs and chipless RFID tags both exploit the physical characteristics, we will include them both here.

- -

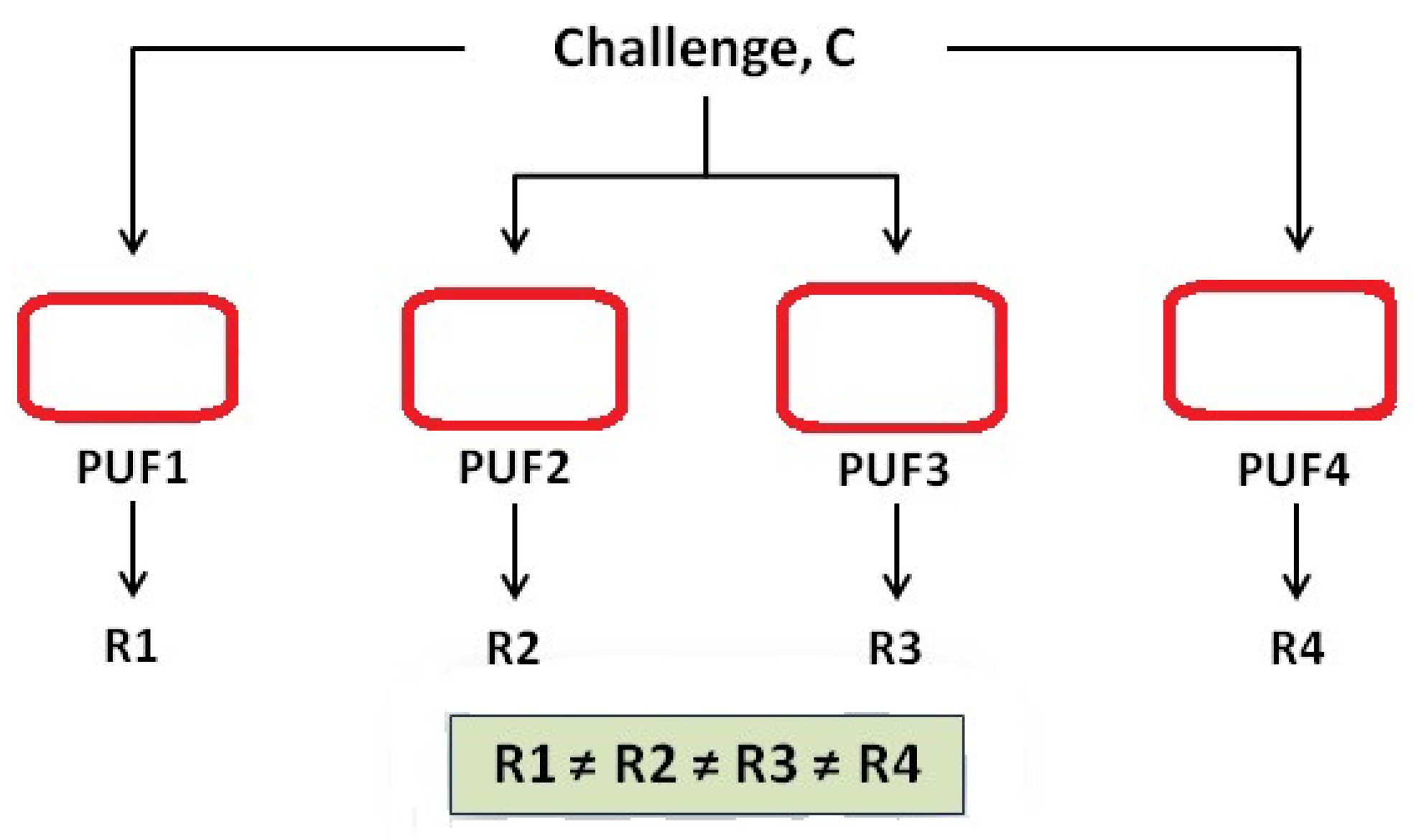

- Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) exploit the physical characteristics of the IC manufacturing process to characterise each and every chip [11] uniquely. This main characteristic will make it impossible to copy, clone or control these chips. This effect makes the RFID ICs attracted to characteristics that provide uniqueness and adequate security. In [12], the authors define the PUF as “a function that maps challenges to responses embodied in a physical object to achieve the simplicity of evaluation and hard to characterize”. By denoting the PUF response to a challenge, C, by and during the verification phase by as is a challenge-response pair. The PUF response according, to a fake PUF, is denoted by Z as the reactions are modeled as random variables with probability distribution . Also, the authors add two more definitions, one for the Integrated Physical Unclonable Function (I-PUF) which is a PUF bounded to a chip which prevents any attempt to separate or remove them from each other as it will lead to the chip destruction. In addition, it has the property of not allowing an attacker to tamper the communications between the chip and PUF as the output is not accessible to an attacker. The best examples for I-PUFs are the silicon PUFs [13] and coating PUFs [14]. Again in [12], the authors construct unclonable RFID tags by embedding I-PUF in the microchips and by using a PUF as a secure memory for storing secret key, as per Figure 1. In [15], the authors discuss the counterfeiting of goods and its implications and threats to health and security. The authors also discuss the incorporation of anti-counterfeiting tags with physical unclonable functions (PUFs) into products as they are unique random physical patterns of taggants which cannot be copied as the PUF tag is the key whereas the stored pattern is the lock. The authors assumed that the stochastic assembly of physical patterns made from taggants exhibiting molecular properties is an excellent approach for designing new PUF keys.

Figure 1. One Challenge with different responses in PUF.

Figure 1. One Challenge with different responses in PUF. - -

- Another technology which received a lot of attention lately is the chip-less RFID tag [16], which is unique and has the advantage of low cost, adaptability and easy printing production. Such tags will be also hard to clone as they need special manufacturing measurements which are hard to determine, but they are not fully un-clonable like the PUF based unclonable RFID tags. As per [17] the chipless RFID tags have the following advantages:

- *

- the extremely low price (as low as 0.1 cents) makes them more appropriate to be used in the supply chain of low-cost commodities.

- *

- elimination of tag memory shelters them from denial-of-service (DoS) attack carried out in the form of overwriting tag memory.

- *

- chipless RFID tags can be directly printed on the products or their packages with conductive 3D printing materials.

The chipless RFID tag is not very well suited for general use, as it requires either removing or shorting some resonators, such as spirals or patch slots, on the tag substrate to represent data and those procedures will increase the manufacturing time and cost [17].

- Track and trace Anti-counterfeiting: This approach has attracted much attention from researchers due to its reliability. The method demands a trustworthy ‘e-pedigree’, or electronic pedigree, that records the product flow of items from manufacturer to retailers [18] to provide evidence of product authentication. To achieve this goal, it is imperative to have reliable creation of e-pedigree and synchronization throughout the supply chain. There are several critical problems addressed by researchers, especially during the generation of the e-pedigree when the products are tagged or during packaging line-transferring when some tags are not provided with the right programming. The synchronization between the tagged items and the back-end database must be carried in real time and with encryption to prevent eavesdropping or sniffing and to ensure uniqueness with the back end e-pedigree records. Examples of such a protocol that uses the track-and-trace method in anti-counterfeiting are shown in Figure 1. This anti-counterfeiting system is designed for supply chain operations where manufacturers, distributors, and retailers are linked to produce, transport and sell brands and products. Without such a system it is possible to import fake products. The system has been adapted and developed by adding TDPS (tag data processing and synchronization), an algorithm based on Gen2 UHF tags that aims to solve critical issues of product initial e-pedigree. The TDPS consists of five steps: EPC writing, EPC Verification and TID reading, tag locking, locking verification and initial e-pedigree creation and synchronization.

- Distance bounding protocols: In [19] the authors proposed leveraging broadcast and collisions to identify cloned tags, thus reducing the need to resort to complex cryptography techniques and tag IDs transmission. The authors argue this approach is the best for large-scale RFID systems and also claim the synchronized secret [20] where it assigns each tag a unique ID and a unique random number which is then stored on a back-end server. The use of leverage broadcast and collision to identify counterfeited tags follows the main idea of choosing a tag with a positive ID and then sending a response when there is a cloned or counterfeited tag peer or peers. If there were a collision or multiple responses then the system will detect these cloned peers. Although this idea is practical and more comfortable to use than complex cryptography techniques, and more pleasant to use in a large scale RFID system accommodating thousands of tagged objects, there is still the limitation when using such a system separately, or in different geographic areas, or in different time frames, as this will require continuous synchronization used with RFID tags in the same system.

- Other types of anti-counterfeiting protocols: These include the use of cryptography in general. There are several protocols which have attempted to address this issue, such as [21], where the authors proposed a system of two protocols as mentioned above. The basic idea is to make the tag handle a one way function F which is compatible with a low-cost RFID tag. The first protocol was the tag authentication protocol where the tag allows the customer “the reader” to inquire about the tag. There are four components of the RFID anti-counterfeiting system: the RFID tag, the reader, the server and the seller. The is a unique tag id for the tag that is attached to the product which also stores the corresponding secret s while the reader is a device used by a customer, such as a tablet or a cell phone, with the application downloaded from the product manufacturer containing the authentication protocol. The manufacturer has the tag database which includes the tag ID or , the secret S, the tag status which can be sold or unsold and the seller name . When issuing a tag, the manufacturer will assign to unsold in the database and every time the tagged product is sold or transferred the database will add the name of the seller to the record.Through this protocol, the server verifies if the product is genuine and notifies the reader if S is incorrect or the item was sold and the server sent invalid message to the reader. The database correction protocol, on the other hand, will correct the database when any legitimate change in the tag status needs to occur.The reader will initiate the procedure by sending the tag ID which can be found on the sticker on the product with the random number to the tag and the tag will check if is correct. The tag will respond with ; otherwise it will terminate. Once the reader has received X, it will generate another random number and send which is an encryption of the server public key. The server will then decrypt the message using a private key and check if the is there in the record; otherwise it terminates. If the is sold, the database sends ; if unsold, the server calculates and checks if . If true, the server sends message and changes tag status to sold. As can be observed, this sequence requires many computational processes as well as encryption, decryption and back-and-forth communications; however, this procedure is still more flexible and reliable than others as it will provide different logical shapes that can adapt to the situation required by the industry.

4. Related Work on Anti-Counterfeiting Systems and Techniques

The purpose of counterfeiting products or the attached tags is to defraud the market, as in creating counterfeit currency, watches and so on. According to a report by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), global market losses reached trillion by 2015 [22] due to counterfeit products. As a result, anti−counterfeiting techniques or solutions such as bar-codes and RFID tags have been proposed. RFID tag counterfeiting can be defined as creating a replica of a tag by either replicating the hardware component of a tag or by copying its software in a way that the genuine reader, database or users would not know the difference between the actual tag and the replicated one. In 2003, RFID technology with the Electronic Product Code (EPC) was proposed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to stop fake drugs [23].

4.1. Schemes and Frame Works to Address Anti-Counterfeiting

As mentioned above, there were many proposed methods in the literature to address the issue of counterfeiting. In [24], the authors proposed a new method for anti-counterfeiting in retail systems which they claimed would provide the level of security required to prevent the counterfeiting of RFID tags attached to products. The proposed protocol addressed the counterfeiting issue as well as other security properties, such as authentication and confidentiality. The proposed scheme establishes strong authentication through the use of shared secrets and randomly generated numbers. The protocol developed trust before exchanging the tags’ information to identify them and determine whether products are counterfeited or not. Since the communication between readers and tags are processed using wireless RF signals in RFID, this gives the opportunity for eavesdroppers to listen to the communication in order to obtain the secret key. Also, the tag’s memory can be read if there is no access control. The proposed protocol was later extended and adjusted to include the security of the IoT, as per [25], to address the scalability in IoT environment but without addressing the counterfeit issue.

RFID systems can be compromised by attacks such as frequency jamming, denial-of-service (DOS), or RFID blocking, as well as by exploiting tag signalling and anti-collision mechanisms. Recently, some work has been done to prevent counterfeiting by proposing anti-counterfeiting techniques and systems. The most recent work was a system introduced by [21]. The system consists of a tag authentication protocol which has four key components: the RFID tag, the reader, the server and the seller, and the database correction protocol which has two players, the seller and the server. The first protocol will authenticate the tags without revealing their sensitive information and allow the customer to inquire if the tag is genuine or not. The database correction protocol will guarantee the correctness of the tag status . The tag authentication protocol will determine if a product is authentic by using and a random number . Also, the authors used a cryptography one−way function F to share the secret S which is known only to the legitimate tag.

For their security analysis, the authors assumed there would be two primary goals of a potential adversary, the first being to counterfeit tags by stealing the secret information of the tags and the second being to corrupt system functionality by attacking the server database. It is claimed that the use of the tag authentication protocol and the database correction protocol can solve these issues. With RFID tag counterfeiting, the adversary must know the secret S corresponding to the tag . Since S is at least 128−bits in length which satisfies the key−size requirement according to ECRYPT II and NIST, this prevents the adversary from undertaking a brute-force search to figure out S according to the authors [21]. Earlier in [26], the authors proposed a possible security mechanism for anti-counterfeiting and privacy protection which uses mutual two-pass authentication and a hash function as well as XOR operation to enhance the RFID tag’s security. Although the protocol can be described as a low-cost protocol which deals with low-cost RFID tags, the protocol is required to store the authorised reader IDs which might lead to further security complications.

4.2. Anti-Counterfeiting Schemes in Different Industries

In [27], the authors presented an anti-counterfeiting system for agricultural production based on five phases and composed of a set of readers and tags, and a data management system. The phases covered are the production phase, process phase, transportation phase, storage phase and sales phase. The idea is to deal with each phase dependently, yet the design needs more elaboration to identify the scenarios of the anti-counterfeiting solution transparently. In [28], the authors discussed the RFID anti-counterfeiting system for liquor products based on RFID and two-dimensional bar-code technologies where the basic idea was to apply RFID technology to authenticate the verification of the liquor product, using the two bar-code technology to verify reader-writer identity in the system. The two-dimensional bar-code is an image file which makes it hard for the verification system to distinguish the correct from the fake or copied bar-code. So the study attempted to combine RFID with a two-dimensional bar-code to apply them to liquor products. The authors used the Cipher system of bar-codes; however, the system design itself depends partially on the bar code which complicates the process and so it will not use the full benefits that the RFID technology can provide. In [29] the authors discussed the new challenge of a pharmaceutical supply chain including fake medicines, indicating the need for an innovative, technology-based solution to protect patents worldwide. The authors’ aim was to identify cutting-edge existing and emerging digital solutions to combat fake medicines. Their literature review identified five distinct categories of technology including mobile, RFID, advanced computational methods, online verification, and blockchain technology. The authors stated that investment in the next generation of technology is essential to ensure the future security and integrity of the global drug supply chain. Digital fake medicine solutions integrate different types of anti-counterfeiting technologies as complementary solutions, improving information-sharing and data collection, and are designed to overcome existing barriers to adoption and implementation.

4.3. Track and Trace Anti-Counterfeiting Schemes

In [30], the authors presented an RFID-based ‘track-and-trace’ anti-counterfeiting system for pharmaceutical drugs and wine products, since these cause massive losses in revenue to producers. Some enterprises used packaging technologies such as holograms, bar-codes, security inks, chemical markers, and the Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) system. There have been many anti-counterfeiting techniques proposed which are either based on offline object authentication or centralised database checking, such as the strengthened Electronic Product Code ‘EPC’ tags for secure authentication, a scheme that employs EPC Class-1 Generation-2 ‘C1G2’ with cryptography features such as Pseudo-random Number Generators (PRNG) and Cyclic Redundancy Checks (CRC) [31]. The anti-cloning protocol, in accordance with the EPC C1G2, uses a unique serial number for all tags and an encrypted EPC [32], and the Call-in Numeric Token (CNT) [33] which is based on the challenges that random or unique ID numbers generated by a back-end server might present.

Generally speaking, offline object authentication which enables the customer to check the tag authenticity via a reader without online network support makes this approach more efficient; on the other hand, it requires more cryptographic algorithms which leads to large memory and expensive tag costs compared to centralised database checking. Additionally, it is less reliable against various attacks and security threats, such as DoS, spoofing, data tampering, and other security threats. Centralised database checking needs a back-end server to check on the authenticity of the tags, even though the tags and reader costs are low as it does not require sophisticated readers or high-cost tags; still, there remain issues of privacy and the issues related to connectivity with the back-end server.

Along similar lines, track-and-trace approaches stand in between offline object authentication and centralised database checking as it does not rely on back-end server either but requires sophisticated readers and tags. According to Cheung [30], there are several practical issues which need to be addressed in the tag-programming layer when it is integrated with computer control systems and into the real-time processing of tag information in the back-end server. Firstly, the tag should be properly bound to a product to prevent counterfeiting, which requires consideration of antenna and skin depth of the product material. Secondly, the tag attached to the product should be destroyed after purchase in order to be sure the tag cannot be used in counterfeiting. Thirdly, the tag programming and database should be synchronized accordingly to maintain monitoring of the products transferred on the manufacturing line as well as ensuring correct tag programming, as partial or incomplete tag programming might occur due to the inappropriate setup of RFID hardware or software control parameters. Errors might cause corruption of the tag data integrity as well as the integrity of the product pedigree. Fourthly, an alternative method for handling wrong tags or duplicated tags should be available in order to solve this problem. Finally, the maximum speed possible on the production line without causing more tag programming difficulties needs to be determined. Cheung [30] proposed a two-layer RFID-based track-and-trace anti-counterfeiting system: the front-end RFID-enabled layer for tag programming and product data acquisition and the back-end anti-counterfeiting layer for processing product pedigree and authentication for high-end bottled products such as brandy and MouTaiwine. The back-end layer consists of a set of system servers that enforce track-and-trace anti-counterfeiting, an information server to collect company information from the server, an authentication server which is used to verify the transaction records, a pedigree server to generate a complete pedigree for the products through the Internet and the mobile network, and a record server which stores the screened records. At the same time, the products are identified by the embedded RFID tags which have the unique tag identification number () used to form the transaction record which will be later verified by the authentication server to detect suspicious activities while the supply chain partners can ascertain the partial product pedigree from the pedigree server. The system faces a couple of implementation issues in RFID-based track-and-trace anti-counterfeiting, such as partial tag programming which can result in data loss. If the tag moving speed is too fast, it might cause the information written on the tag to be incomplete. Another implementation issue is duplication error, when the unique number is programmed into two or more tags which might hamper subsequent product authentication. A case study on implementation problems concluded that the use of a C1G2 UHF RFID reader for tag programming was best achieved by designing an EPC numbering scheme for product identifier and implementation for tag programming. In [34], the authors present an innovative track-and-trace anti-counterfeiting system for products and discussed several data management issues, such as e-pedigree formatting, data synchronization and traceability control. Track-and-trace for anti-counterfeiting in SCM was first proposed in [35] and analysed/modified in [36,37,38,39,40]. While the researchers developed a comprehensive data structure for modelling apparel e-pedigree with a data synchronization mechanism to ensure the integrity and reliability of product e-pedigree data, such as item-level transaction records, pallet-level containment relationships and batch level order information, the authors did not elaborate on the privacy issues that are associated with this anti-counterfeiting technique. Also in [18], the authors present a new track-and-trace anti-counterfeiting system and then propose a tag data processing and synchronization (TDPS) algorithm to produce e-pedigrees for products.

4.4. Distance Bounding and Collision in Identifying Coned RFID Tags

In [41], the authors proposed leveraging broadcast and collision to identify cloned tags, which is different to most available techniques in cloned tag detection since most prevention techniques are based on cryptography and encryption such as [42,43]. This method was identified by the authors as being unaffordable for low-cost tags [44,45] as well as having the disadvantages of restoring complex cryptography techniques and time-consuming transmission of the tag IDs. The authors also proposed a suite of time-efficient protocols approaching the lower time bound where they claimed the execution time of their protocol is only times the value of the lower bound. In [46], a survey on RFID systems presented most popular anti-collision protocols, such as the Aloha-based protocols, and its variants, such as PA with Muting, PA with slow down, PA with fast Mode, and other modifications. The authors elaborated on each protocol and explained the differences including the family of Slotted Aloha (SA) and its variants, such as SA with muting slow down, SA with an early end, SA with an early end and muting, and SA with slow down and early end. The third protocol group is Framed Slotted Aloha (FSA) which includes basic FSA (BFSA), BFSA non-muting, BFSA muting, BFSA non-muting early end, BFSA muting early end, and dynamic frame slotted aloha (DFSA). In addition, there were tree-based protocols such as Tree splitting, Query tree (QT), Binary search (BS) and Bitwise arbitration (BTA) and other variants.

4.5. The Use of Physical Unclonable Function (PUF)

Since cloning the tag is copying its contents including the unique identifier from the actual tag to the other, the authors suggested that the breakthrough in preventing cloning of low-cost tags will be in the adoption of physically unclonable functions (PUFs). A PUF generates tag profiles using their physical properties which are hard to crack and clone; yet, it will be tough for PUF to generate physical profiles for all of the shelf tags as the authors suggest. Also in [12], the authors gave an elaboration on RFID tags for anti-counterfeiting using PUFs as well as the I-PUF and PUF-Certificate-Identity-based Identification (PUF-Cert-IBI) scheme. In [11], the authors have highlighted the advantages of using PUFs which exploit the variation in physical properties of integrated circuits (IC) due to manufacturing process variations; they concluded that PUF-enabled RFIDs provided secure and robust authentication with minimal overheads which can be applied to a low-cost tag, as compared with the traditional track-and-trace approach or cryptographic approach. In [19], the paper investigates the detection of a cloned tag by using distance bounding based on tag collision to achieve a better time-turnaround result. The idea of not using complex cryptographic techniques makes the system more efficient. It was observed that the synchronized secret (SYNC) was broadcast-unfriendly when an original tag and its cloned peer is within the interrogation region of a reader which causes two cases of collision, in both of which SYNC fails to identify the cloned tags. Also in this paper, the author adopted an attack model as in [42], where an attacker replicates a valid tag and uses the cloned tag to authenticate other objects and then pose a threat to RFID Applications. The author’s contribution also came from designing a time-efficient cloned-tag identification protocol for secure applications claimed to be able to identify all cloned tags rather than detect them by leveraging broadcasts and collisions in a large scale RFID system as fast as possible. In [28], the authors proposed a liquor product anti-counterfeiting system based on RFID and two-dimensional bar-code technology after they described the issues with applying 2D bar-code with RFID to commodity anti-counterfeiting. As the two-dimensional bar-code is an image file, the verification system cannot distinguish the original from the copied image file given that the RFID communication channel is open making it easy to leak this information to an illegal reader-writer. The authors also tried to combine RFID with a two-dimensional bar-code for use in liquor anti-counterfeiting by using RFID for authentication while using the two-dimensional bar-code technology for legality verification of reader-writer identity [28].

4.6. Using RFID Tag ID Verification for Anti-Counterfeiting

As RFID Anti-counterfeiting systems are based on the principle of writing a unique code (UID) into the tag attached to the product package and then storing this UID in a verification system. Once it is verified, the tag will be activated and send the UID to the reader-writer which in its turn will send this information for further investigation. On the one hand, the two-dimensional bar code records the data and creates an image file in black and white and encrypts the information. Also, the verification system will decode the data, so all that the consumer has to do is to take a picture of the image file and send it to the verifier for authenticity verification. The proposed anti-counterfeiting system in [27] was based on a combination anti-counterfeiting scheme between the RFID system and the 2D-bar code. The method starts when the tag enters the interrogation zone of the reader-writer as it sends a two-dimensional bar-code to the anti-counterfeiting verification platform which will decrypt the 2D bar-code, verify the ID of the reader-writer and then cancel the information of the product once it has been confirmed. Also, a fragile paper electronic tag was stuck on the opening of the wine box so that the tag will be damaged once the wine box is opened to prevent reclamation. In [47], the authors proposed a new idea to enhance hardware-enabled authentication and anti-counterfeiting ability which requires the use of a ‘super tag’ that uses RF-COA, not only digitally but also physically unique and hard to fake. The main idea is to complement an RFID tag with an inexpensive physical object that behaves as a certificate of authenticity (RF-COA) within an electromagnetic field range. The cost of such technology remains an open issue and is not considered by the authors. In [48], the authors classified counterfeiting activities into four distinct categories: knockoffs, counterfeits that are reverse-engineered from genuine goods, goods produced by outsourced suppliers on third shifts, and goods that do not meet a manufacturer’s standards but have not been destroyed or put out. The author described the first type ‘knock-off’ as a lookalike or duplicate copy of the genuine product that the customer might be aware of, which is possible to easily detect due to its low price and quality. The second type, which we will address and target in this research, consists of mostly genuine products that are reverse-engineered through the use of copied or stolen blueprints or bypassing of software copy protection. The third category of counterfeits is produced by an outsourced supplier using a third shift which the genuine manufacturer is unaware of. The fourth type of product counterfeiting cover goods produced by outsourcing suppliers which do not meet the manufacturer’s standards but have not been discarded as ‘seconds’ or destroyed. The authors also discuss how to detect and develop a new strategy to identify and reduce counterfeiting activity via a four-step plan which consists of developing early warning signals of counterfeiting; budgeting to monitor and remove counterfeiting; using demand-side strategies to deter counterfeiting; and using supply-side approaches to prevent counterfeiting. Earlier in [49], the authors surveyed and remedied the technologies used for RFID tags against counterfeiting, presented an overview of the RFID tags counterfeiting issue and studied the methods employed for cloning the tags. In addition, they also compared and contrasted the pros and cons of these different methods and proposed some design principles and guidelines for decreasing the opportunity adversaries have for cloning. The authors elaborate on the earlier Juels Anti-counterfeiting tag [50] which is based on increasing the complexity of cloning the legitimate tag through eavesdropping. Eavesdropping is done by sending a set of spurious kill PINs plus a correct Kill PIN in the same sequence in the q kill PIN to trick the attacker and strengthen the method by adding another layer of security, focusing on the design of an additional access PIN command. Duc et al. [31] thought that the Juels’ method did not take the threat of information leakage and privacy issues into account, so they proposed another anti-counterfeiting mechanism to solve this problem. The work in [51] addressed the problems that face the authentic pharmaceuticals industry and introduced an architecture design for storing and searching pharmaceuticals RFID event data. Later, they discuss the viability of RFID-based anti-counterfeiting with respect to its impact and address the challenges in pharmaceutical supply chains when the European pharmaceutical industry announced that 34 million fake drugs were detected while operating the MEDI-Fake operation [52], an increase of 118 percent in pharmaceutical counterfeits detected in 2008 compared with 2007. They did present architectures for processing RFID event data and included their experience and performance for prototype implementation; also, they presented business considerations for RFID usage of participants in the pharmaceutical supply chain. In [53], the authors proposed a new mutual authentication protocol in RFID systems that uses an ID tag encrypted with a hash function and a stream cipher-based OTP by a challenge-response pair of PUFs, which was invented by Naccache and Fremanteau in 1992 [54]. Thus, there is no crucial disclosure problem in the protocol. The OTP is generated by using a NLM-128 generator which is simple, easy to implement in the hardware and software and is highly secure as any one-way hash function can create most OTPs. The proposed protocol was based on the idea of using the PUF output to generate a transient key dynamically. In [55] the authors proposed a product life cycle monitoring information system based on RFID and IoT by integrating the technical advantage of RFID with IoT, design products, monitoring function modules and product anti-counterfeiting. The contribution of this paper was to use the Jigsaw algorithm to address security and authentication for RFID tags of Class 1 Generation 1 requirements so that many customers can benefit from this proposed algorithm and apply it to their applications. In [56], the researchers targeted the issue of counterfeiting in large-scale RFID applications such as supply chains, retail industry and pharmaceutical industry. They developed an FSA-based protocol (FTest) for batch authentication in large-scale RFID applications as FTest can determine the validity of a batch of tags with minimal execution time. They provided an experiment and compared the results with other existing counterfeit detection approaches, yet failed to measure the accuracy of the batches compared to the per tag authentication protocols. The authors classified the current anti-counterfeiting technologies into four groups based on previous studies in [57,58]: overt technology such as holograms; covert technology including security inks and invisible printing; forensic features and track-and-trace using RFID technology; and bar-codes which was described as having the ability to protect the whole supply chain against infiltration, boost SCM efficiency, eliminating theft and fraud, and enable recall of defective products and remote authentication support. In [59], e-pedigree generation, synchronization, retrieving, and system security are among the technical problems which need attention. In [60], autonomic tracing of production processes with mobile agent-based computing (highly dynamic and cooperative, based on the idea of considering the closest provider to a buyer) was proposed; it relies on the use of agent-based ubiquitous computing technologies. In [53], the authors proposed a new mutual authentication protocol in RFID systems that uses an ID tag which is encrypted with a hash function and a stream cipher-based OTP by a challenge−response PUF [54]. There is no crucial disclosure problem in this protocol as the OTP is generated by using a NLM-128 generator which is simple, easy to implement in the hardware and software and highly secure as any one-way hash function can produce most of OTPs. The proposed protocol was based on the idea of using the PUF output to generate a transient key dynamically. In [24], the authors presented a new method to manage RFID tags in the supply chain and to preserve tags and goods from counterfeiting by using a new protocol, the ‘Matryoshka protocol’. The protocol was able to present a new method in managing RFID tags that would reduce the reads to a minimum to achieve better security and privacy results.

4.7. Anti-Counterfeiting and a Secure Tag Ownership Transfer Mechanism

Another topic that anti-counterfeiting protocols did not discuss in detail is RFID tag ownership transfer. It is essential for the RFID tag to be used more than once in its life cycle by changing its ownership from one owner to another many times to use its longevity and make the passive tag more economical [61]. The process of tag ownership transfer, just like RFID security which was addressed in detail in [62], is one of the critical requirements for the global implementation of networked RFID systems [63]; a proper design for RFID anti-counterfeiting associated with RFID tag ownership transfer would be needed. Currently, we are working on a secure scheme which will provide a secure ownership transfer mechanism as well as addressing the anti-counterfeiting problem in one single framework, as such a framework will be very useful to the industry.

5. Comparison Discussion

In the table below, we make a comparison of the four types of methods used to address counterfeiting. We also mention the pros and cons of each technology. As seen in Table 1 and Table 2, the physical, such as PUF-based RFID and chipless anti-counterfeiting techniques, use a high amount of resources due to manufacturing requiring specific characteristics compared to other techniques. Also, we can see it has medium complexity, high security, low adaptability, and high limitations, all covered fairly by researchers; thus, it has the disadvantage of high cost and not being adaptable to every industry and it is impossible to clone. On the other hand, the track-and-trace technique for RFID-based anti-counterfeiting uses medium resources although it requires a huge database, has medium complexity and security with low limitations, with high adaptability, as covered extensively in the research. It needs a trusted e-pedigree which make it more reliable in the industry, yet has the issue of synchronization between tagged items and back-end database. The distance-bounding protocols for RFID based anti-counterfeiting technique have medium use of resources, is low in complexity, has high security and limitations but it is low in adaptability. Since it uses broadcast and collision to identify cloned tags, it is best for large-scale RFID tags, but has the disadvantage when used in different geographical areas. The Cryptography based RFID anti-counterfeiting method is very low in resources, has a high complexity, good security, high adaptation and low limitation and was covered fairly in the research. It is very low cost, yet it can be compromised once the secret key is obtained by an adversary, so the security measures need to be strengthened.

Table 1.

A comparison between the four anti-counterfeiting methods.

Table 2.

Pros and Cons of each RFID anti-counterfeiting technique or method.

6. Conclusions

Counterfeiting has always been a problem that causes many losses for retail markets. While there has been some work done to address this problem and provide some solutions, especially in the retail market, there is still a knowledge gap not addressed or not covered in details. Some methods which we highlighted above address this issue and provide a solution that can save retailers millions of dollars per annum. In this paper, we have presented a detailed survey of the literature in RFID-based anti-counterfeiting methods and undertaken a detailed analysis of the different approaches and techniques that were used in the literature and industry by researchers. We addressed each method’s advantages and disadvantages compared to each other based on the technology it uses, taking into consideration each technology’s adaptability and limitations. Some possible future directions would be designing a new RFID anti-counterfeiting framework that uses two or more technique together to achieve better security, privacy and adaptability for RFID anti-counterfeiting systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K., R.D. and M.C.; methodology, G.K.; validation, G.K., R.D. and M.C.; formal analysis, G.K., R.D. and M.C.; investigation, G.K.; resources, G.K., R.D. and M.C.; data curation, G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.K.; writing—review and editing, R.D. and M.C.; supervision, R.D., M.C.; project administration, R.D., M.C.; funding acquisition, G.K., R.D.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

We are the authors of “A Comparison Survey Study on RFID tag Anti-Counterfeiting Systems” we declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Randhawa, P.; Calantone, R.J.; Voorhees, C.M. The pursuit of counterfeited luxury: An examination of the negative side effects of close consumer–brand connections. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2395–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T. Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement: 2010–2012 European Parliament Discussions. In The Politics of Online Copyright Enforcement in the EU; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 247–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaladevi, B. RFID-The best technology in supply chain management. Int. J. Innov. Manag. Technol. 2010, 1, 198. [Google Scholar]

- Al, T.; Al, G.K. A Case Study in Developing the ICT Skills for a Group of Mixed Abilities and Mixed Aged Learners at ITEP in Dubai-UAE and Possible Future RFID Implementations. In Envisioning the Future of Online Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Al, G. RFID Technology: Design Principles, Applications and Controversies; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Commack, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peppa, V.P.; Moschuris, S.J. RFID technology in supply chain management: a review of the literature and prospective adoption to the Greek market. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2013, 15, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Soon, C.B.; Gutiérrez, J.A. Effects of the RFID mandate on supply chain management. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2008, 3, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Peng, P.; Dang, F.; Wang, C.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, Y. Anti-counterfeiting via federated rfid tags’ fingerprints and geometric relationships. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Communications (INFOCOM), Hong Kong, China, 26 April–1 May 2015; pp. 1966–1974. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, K.; McCathie, L. The pros and cons of RFID in supply chain management. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mobile Business (ICMB’05), Sydney, Australia, 11–13 July 2005; pp. 623–629. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, L.; Laurent, M.; El Moustaine, E. Risk assessment along supply chain: A RFID and wireless sensor network integration approach. Sens. Transducers 2012, 14, 269. [Google Scholar]

- Devadas, S.; Suh, E.; Paral, S.; Sowell, R.; Ziola, T.; Khandelwal, V. Design and implementation of PUF-based “unclonable” RFID ICs for anti-counterfeiting and security applications. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on RFID, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 16–17 April 2008; pp. 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tuyls, P.; Batina, L. RFID tags for Anti-Counterfeiting. In Proceedings of the Cryptographers Track at the RSA Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 13–17 February 2006; pp. 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Gassend, B.; Clarke, D.; Van Dijk, M.; Devadas, S. Silicon physical random functions. In Proceedings of the 9th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Washington, DC, USA, 18–22 November 2002; pp. 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tuyls, P.; Škorić, B. Secret key generation from classical physics: Physical uncloneable functions. In AmIware Hardware Technology Drivers of Ambient Intelligence; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 421–447. [Google Scholar]

- Arppe, R.; Sørensen, T.J. Physical unclonable functions generated through chemical methods for anti-counterfeiting. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preradovic, S.; Karmakar, N.C. Chipless RFID: Bar Code of the Future. IEEE Microw. Mag. 2010, 11, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Botero, U.; Shen, H.; Woodard, D.L.; Forte, D.; Tehranipoor, M.M. UCR: An Unclonable Environmentally Sensitive Chipless RFID Tag For Protecting Supply Chain. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. 2018, 23, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Yang, B.; Cheung, H.; Yang, Y. RFID tag data processing in manufacturing for track-and-trace anti-counterfeiting. Comput. Ind. 2015, 68, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, K.; Liu, X.; Xiao, B. Approaching the time lower bound on cloned-tag identification for large RFID systems. Ad Hoc Netw. 2014, 13, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, M.; Ostojic, D.; Ilic, A.; Michahelles, F. Securing RFID systems by detecting tag cloning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pervasive Computing, Nara, Japan, 11–14 May 2009; pp. 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D.T.; Hong, S.J. RFID anti-counterfeiting for retailing systems. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 2015, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, C.; Keates, S. An Overview of Branding and its Associated Risks. In Countering Brandjacking in the Digital Age; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Compliance Policy Guid 160.900 Prescription Drug Marketing Act-Pedigree Requirement under 21 CFR Part 203. 2006. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/cpg-sec-160900-prescription-drug-marketing-act-pedigree-requirements-under-21-cfr-part-203 (accessed on 30 September 2016).

- Al, G.; Doss, R.; Chowdhury, M.; Ray, B. Secure RFID Protocol to Manage and Prevent Tag Counterfeiting with Matryoshka Concept. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Future Network Systems and Security, Paris, France, 23–25 November 2016; pp. 126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Al, G.; Doss, R.; Chowdhury, M. Adjusting Matryoshka Protocol to Address the Scalability Issue in IoT Environment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Future Network Systems and Security, Gainesville, FL, USA, 31 August–2 September 2017; pp. 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.C.; Wang, W.L.; Hwang, M.S. RFID authentication protocol for anti-counterfeiting and privacy protection. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology, Kobe, Japan, 12–14 February 2007; Volume 1, pp. 255–259. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Gao, W.; Yu, L.; Li, P.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Du, J. Research on RFID-based anti-counterfeiting system for agricultural production. In Proceedings of the World Automation Congress (WAC), Kobe, Japan, 19–23 September 2010; pp. 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Cao, L. Liquor Product Anti-counterfeiting System Based on RFID and Two-dimensional Barcode Technology. J. Converg. Inf. Technol. 2013, 8, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, T.K.; Nayyar, G. A review of existing and emerging digital technologies to combat the global trade in fake medicines. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2017, 16, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, H.; Choi, S. Implementation issues in RFID-based anti-counterfeiting systems. Comput. Ind. 2011, 62, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, D.N.; Lee, H.; Kim, K. Enhancing Security of EPCglobal Gen-2 RFID against Traceability and Cloning. In Proceedings of the SCIS 2006, Hiroshima, Japan, 17–20 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Lim, J.I. Anti-cloning protocol suitable to EPCglobal Class-1 Generation-2 RFID systems. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2009, 31, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.G. An anticounterfeiting strategy using numeric tokens. Int. J. Pharm. Med. 2005, 19, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Yang, B.; Cheung, H.; Yang, Y. Data management of RFID-based track-and-trace anti-counterfeiting in apparel supply chain. In Proceedings of the 2013 8th International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST), London, UK, 9–12 December 2013; pp. 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, R.; Schuster, E.W.; Chackrabarti, I.; Bellman, A. Securing the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain; White Paper; Auto-ID Labs, Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Staake, T.; Thiesse, F.; Fleisch, E. Extending the EPC network: the potential of RFID in anti-counterfeiting. In Proceedings of the 2005 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Santa Fe, NW, USA, 13–17 March 2005; pp. 1607–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Staake, T.; Michahelles, F.; Fleisch, E.; Williams, J.R.; Min, H.; Cole, P.H.; Lee, S.G.; McFarlane, D.; Murai, J. Anti-counterfeiting and supply chain security. In Networked RFID Systems and Lightweight Cryptography; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H. Anti-Counterfeiting Solution Employing Mobile RFID Environment; World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen, M.; Staake, T.; Michahelles, F. From identification to authentication–a review of RFID product authentication techniques. In Networked RFID Systems and Lightweight Cryptography; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Poon, C. An RFID-based anti-counterfeiting system. IAENG Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2008, 35, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, D.L. Integrating the Electronic Product Code (EPC) and the Global Trade Item Number (GTIN). White Paper. 2001. Volume 25. Available online: www.autoidcenter.org/pdfs/MIT-WUTOID-WH-004.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2007).

- Abawajy, J. Enhancing RFID tag resistance against cloning attack. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Network and System Security, Gold Coast, Australia, 19–21 October 2009; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou, T. A lightweight RFID protocol to protect against traceability and cloning attacks. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Security and Privacy for Emerging Areas in Communications Networks (SECURECOMM’05), Athens, Greece, 5–9 September 2005; pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, S. Some issues related to RFID and Security. In Proceedings of the Vortrag am zweiten Workshop über RFID Security (RFIDSec’06), Graz, Austria, July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spiekermann, S.; Evdokimov, S. Privacy enhancing technologies for RFID-A critical investigation of state of the art research. IEEE Priv. Secur. 2009, 7, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klair, D.K.; Chin, K.W.; Raad, R. A survey and tutorial of RFID anti-collision protocols. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2010, 12, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakafosis, V.; Traille, A.; Lee, H.; Orecchini, G.; Gebara, E.; Tentzeris, M.M.; Laskar, J.; DeJean, G.; Kirovski, D. An RFID system with enhanced hardware-enabled authentication and anti-counterfeiting capabilities. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest (MTT), Anaheim, CA, USA, 23–28 May 2010; pp. 840–843. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, B. Strategies to detect and reduce counterfeiting activity. Bus. Horizons 2008, 51, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, A.B.; Chang, L.C.; Wei, T.E. Survey and remedy of the technologies used for RFID tags against counterfeiting. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics, Baoding, China, 12–15 July 2009; Volume 5, pp. 2975–2981. [Google Scholar]

- Juels, A. Strengthening EPC tags against cloning. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM workshop on Wireless Security, Cologne, Germany, 2 September 2005; pp. 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schapranow, M.P.; Müller, J.; Zeier, A.; Plattner, H. Costs of authentic pharmaceuticals: Research on qualitative and quantitative aspects of enabling anti-counterfeiting in RFID-aided supply chains. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2012, 16, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyun, G. 2008 Pro-IP Act: The Inadequacy of the Property Paradigm in Criminal Intellectual Property Law and Its Effect on Prosecutorial Boundaries. DePaul J. Art Tech. Intell. Prop. L. 2008, 19, 355. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, H.J. Mutual authentication protocol for enhanced RFID security and anti-counterfeiting. In Proceedings of the 2012 26th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops (WAINA), Fukuoka, Japan, 26–29 March 2012; pp. 558–563. [Google Scholar]

- Kardaş, S.; Çelik, S.; Bingöl, M.A.; Kiraz, M.S.; Demirci, H.; Levi, A. k-strong privacy for radio frequency identification authentication protocols based on physically unclonable functions. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2015, 15, 2150–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Huang, G. Application of RFID and Internet of Things in Monitoring and Anti-counterfeiting for Products. In Proceedings of the International Seminar on Business and Information Management, Wuhan, China, 19 December 2008; Volume 1, pp. 392–395. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, F.; Ahamed, S.I. Efficient detection of counterfeit products in large-scale RFID systems using batch authentication protocols. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2014, 18, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, D.; Malla, S.; Gudala, K.; Tiwari, P. Anti-counterfeit technologies: A pharmaceutical industry perspective. Sci. Pharm. 2013, 81, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L. Technology designed to combat fakes in the global supply chain. Bus. Horizons 2013, 56, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, G. Anti-Counterfeit Technologies for the Protection of Medicines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cimino, M.G.; Marcelloni, F. Autonomic tracing of production processes with mobile and agent-based computing. Inf. Sci. 2011, 181, 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al, T.; Al, G.K.; Ram Mohan Doss, R. A Survey on RFID tag ownership transfer protocols. In RFID Technology: Design Principles, Applications and Controversies; Al, G.K., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppage, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Al, T.; Al, G.K.; Ram Mohan Doss, R. Survey on RFID Security Issues and Scalability; Al, G.K., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppage, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Al, G.; Ray, B.; Chowdhury, M. Multiple Scenarios for a Tag Ownership Transfer protocol for A Closed Loop System. IJNDC 2015, 3, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).