Abstract

With the increase of mobile terminals, routing protocols in wireless communications must provide better quality of service to meet bandwidth and reliability requirements. In networks without infrastructure, such as ad hoc and sensor networks, where a device performs as both a terminal and a router to forward data of other nodes, maintaining the network topology consumes considerable resources in terms of energy and bandwidth. These parameters need to be considered when designing routing protocols for wireless networks. To reduce the cost of the protocol overhead, some algorithms act on the forwarders, while others act on the transmission of messages. Finally, the hybrid ones are a combination of both. In this paper, we propose a new algorithm with two zoning strategies to enhance the performance of mobile network. The first strategy helps to select dispersive forwarders in order to reduce the collision in radio channel. The second strategy aims to reduce the transmission of redundant messages. Both strategies are based on the location information of nodes. We implemented our algorithm in the optimized link state routing protocol, the most used protocol in mobile ad hoc networks. We showed by simulations that our solution reduces drastically the cost of the overhead with no hindrance to the network topology.

1. Introduction

In the last few years, several studies have been carried out with the aim of miniaturizing computer technology, which gave rise to the Internet of things [1]. The ubiquitous objects provide many daily tasks to make human life easier by sensing the environment and applying knowledge [2]. They affect many domains including wireless sensors [3], mobile ad hoc networks [4], smart cities, unmanned airplanes, smart transport, and smart homes, to name a few [5]. The smart objects need to interact with each other to exchange information about their environment or to communicate with the cloud [6]. Due to various applications of smart environment, different communication technologies and hardware systems must coexist together. These networks vary in size and area covered, and need precision for more security, especially in delay-sensitive environment where the probability of collision increases [7]. The network latency and the packet loss are the main factors that affect the delay [8].

The routing protocols in smart environment have to deal with the lack of resources in smart devices [9]. The proactive mobile ad hoc network (MANET) protocols, such as the optimized link state routing protocol (OLSR) [10] where the routes are already calculated, help to reduce the response time of devices. However, each node has something to say every couple of seconds. With high density of nodes in a shared space, the packet loss and the network latency increase drastically [11]. The OLSR adopted the Multipoint Relays (MPR) concept to reduce the overhead related to the protocol. However, the MPR concept suffers from broadcast redundancies and collision in the radio channel, especially at the level of MPR nodes. Many studies have been conducted to reduce the cost of overhead in OLSR [12,13]. Some solutions have made changes to the MPR computation in order to select different MPR based on metrics such as velocity, energy, location, signal range, etc. Other solutions focus on the transmission of messages, especially the broadcast transmissions.

In this paper, we use a combination of two zoning techniques to decrease the cost of the routing protocol overhead and to ensure better quality of service (QoS) [14]. Our solution acts locally based on one-hop neighbor information in order to select dispersive dominant nodes to decrease the collision at the level of MPRs. The second method acts globally on the entire network. It divides the network into multiple propagation zones and it avoids useless transmissions between nodes of different zones. In previous work, we proposed the Zone Multipoint Relays (Z-MPR) [15], an improved algorithm that optimizes the MPR computation in OLSR. In another work, we proposed a zoning technique to avoid the useless transmission of topology control (TC) messages that gave birth to the Geographic Forwarding Rules (GFR) [16]. In this paper, we propose a solution that combines the two techniques within the same algorithm called Zone Geographic Forwarding Rules (Z-GFR). The local zoning technique and the overall zoning technique are different. However, both techniques coexist and operate in the same routing algorithm in a distributed manner. The Z-GFR reduces the number of transmissions of topology control messages while it assumes good propagation of the topology and ensures better QoS [17] for applications.

The remainder of the current paper is organized as follows: Section 2 summarizes some hybrid techniques that aim to reduce the overhead in mobile ad hoc network. Section 3 describes the problem formulation and discusses our proposed solution. In Section 4, we present the modeling of the OLSR protocol. Section 5 details the hybrid solution zone geographic forwarding rules in the context of OLSR protocol. The first strategy is presented in Section 5.2, while Section 5.3 details the second strategy. The performance of the proposed algorithm is presented via simulations in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Many studies have been carried out to reduce the cost of the protocol overhead in mobile communication. They aim to reduce the consumption of energy or to increase the reliability of the network. These techniques change the structure of nodes or reduce the number of transmissions. The authors of [18] proposed an improved hybrid location-based ad hoc routing (IHLAR) that combines topology-based routing and geographic routing to enhance the route request (RR) in Ad hoc On demand Distance Vector (AODV) protocol. Each node in IHLAR maintains a table of surrounding neighbors, as a virtual zone, that are at (p) hops. When establishing a RR, a source node or intermediate node uses pure flooding if the destination is within (p) hops and greedy-forwarding between virtual zones if the destination resides outside its zone. This mechanism helps to reduce the end-to-end delay related to the RR in case of long distance between a pair of nodes. However, the geographic routing leads to blockage when an intermediate node has no link to adjacent zone which may increase the delay.

The authors of [19] proposed a hybrid algorithm to select a limited number of nodes as relays. The algorithm defines a reply area. It is the intersection between the signal range and the angle calculated based on the line between the source and the destination. As first optimization, only nodes inside the reply area relay the RR. As the second, and based on the location information received from the sender, a relay node calculates the distance between itself and the destination, and between the sender and the destination. The intermediate node rebroadcasts the packet only if it is closer to the destination than the initiator. This algorithm reduces the number of transmissions and redundant packets by choosing a small number of relay nodes. However, it needs to know previously the position of the destination nodes, which is not always available.

In zone based multi-cast routing protocol (ZBMRP) [20], the authors combined a zoning technique with AODV protocol to reduce the overhead of multi-cast flooding. ZBMRP uses the route reply to organize nodes into groups to build multiple mesh networks along the source to the multi-cast destinations. Then, it uses tunneling technology to achieve packets between zones. The simulations showed that ZBMRP performs better than other multi-cast protocols in term of packet delivery ratio. However, The initiation phase to establish mesh networks increases the start of the multi-cast communication, which increases the end-to-end delay.

The authors of [21] proposed core enabled hybrid routing (CEHR) protocol, which combines proactive and reactive mechanism to reduce the topology information generation in MANET. CEHR forms different subset of nodes called Core Nodes Set (CNS). Proactive traffic is allowed inside each CNS, while reactive traffic ensures inter zone communication. The proactive routing inside the CNS is enabled by Core Node (CN). This algorithm helps to reduce the transmission of the topology information and the RR between the CNS which enhances the packet delivery ratio. However, CEHR increases the size of control messages which impacts the throughput negatively.

The authors of [22] proposed a hybrid algorithm based on the Cellular Automata (CA) and African Buffalo Optimization (ABO) algorithm in order to optimize the path selection and to decrease the energy consumption. The algorithm is integrated with AODV protocol and tries to enhance its QoS. AODV protocol sends the data packets after receiving the first route reply. However, AODV does not take into account the residual energy of nodes, which increases the link failure if one node dies. The major goal of CAABO is to establish route from the source to the destination that satisfies the QoS requirements of end-to-end delay and energy consumption that AODV neglects. However, the CAABO increases the size of the RR, such as CEHR, in order to introduce the QoS parameters which impacts the throughput.

The authors of [23,24,25] proposed to organize nodes into groups called clusters. They elected in each cluster a node named cluster head (CH) responsible of data dissemination and forwarding inside the group. In [23], the authors proposed an efficient energy-aware predictive clustering scheme for vehicular networks. They used the previous positions of vehicles to predict their future position and form a cluster of vehicles driving in the same direction. This technique prolongs the duration of cluster membership and avoids re-electing new clusters in case of vehicles that are driving in the opposite direction. Maximizing cluster membership reduces the traffic related to cluster construction and frees the channel for data communications.

In Node Ranked Low Energy Adaptive Clustering Hierarchy (NR-LEACH) protocol [24], the authors distributed the energy load of sensors in a good manner among all nodes by CH rotation process in order to prolong the lifetime of the network. NR-LEACH uses node rank algorithm that combines path cost between nodes, number of links between nodes and residual energy. The node with high rank is selected to act as a CH. NR-LEACH helps to prolong the lifetime of nodes, However, re-electing the CH increases the lost packets because the network remains unavailable between two elections.

The clustering techniques have proved their ability to enhance the performance of the network and prolong the lifetime of node. However, they still suffer from time delay associated to cluster formation, which slows communication till the clusters are constructed.

3. Problem Formulation

The nature of mobile ad hoc networks and the routing protocols require the use of flooding mechanisms to function properly and to build a network. The flooding process ensures several functions such as neighborhood discovery, topology dissemination and maintenance, warning system, etc. The OLSR protocol elects dominant nodes based on topology-based heuristic to act as forwarders of broadcast messages. However, the forwarders can be grouped into one area and their density increases accordingly, creating large broadcast zones. The larger the broadcast zone is, the bigger the collision would be. The collision increases the loss of packets and decreases the reliability of the network.

The broadcast messages are propagated from one node to another until covering the entire network. The MPR concept of OLSR reduces the number of transmissions of TC messages. However, it suffers from redundancies. We consider a transmission as redundant when a node receives the same message more than once since it is neighbor of multiple MPR. These useless messages consume resources such as bandwidth and cause packets loss. With the increase of the density and the number of nodes, the broadcasting becomes extremely resource-intensive.

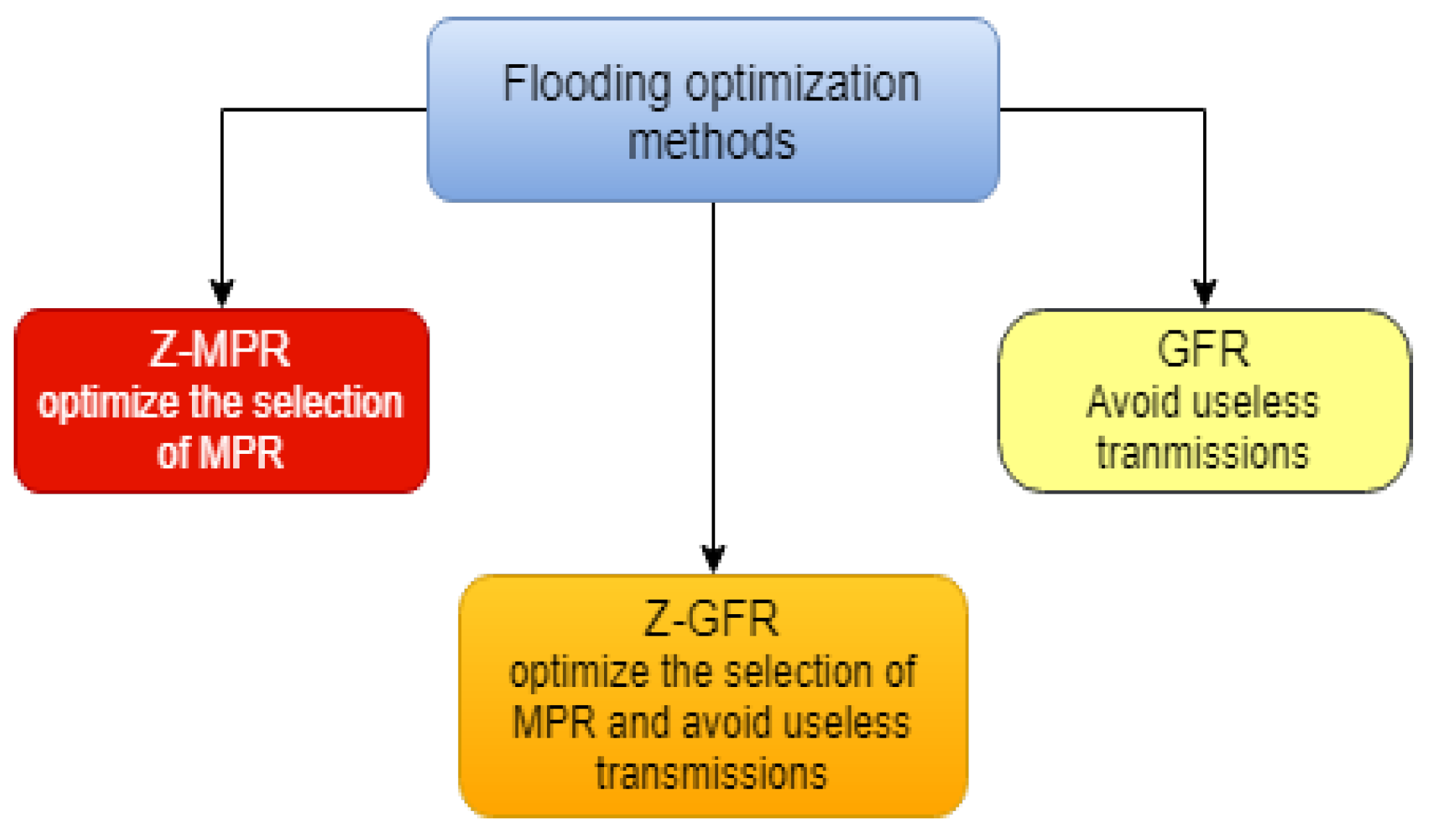

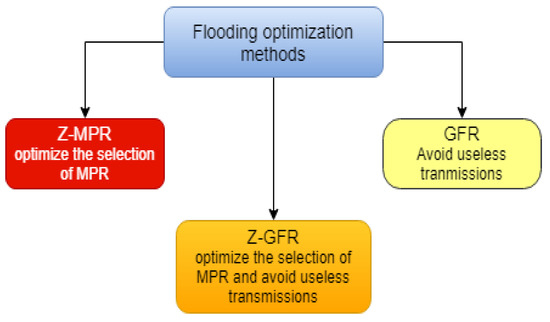

In this paper, we act on both nodes and messages to reduce the cost of topology dissemination in OLSR protocol. We combine the Z-MPR and GFR in the same protocol called Z-GFR, as shown in Figure 1. Both algorithms propose a context-based heuristic based on the location information of nodes. The Z-GFR exploits the position of nodes provided by the location service, such as GPS in open areas or Received Signal Strength Indicator in indoors [26,27,28]. We assume that each node knows its position while the coordinates of the other nodes are regularly advertised throughout the network during the topology building process.

Figure 1.

Z-GFR: Two optimization strategies.

To reduce the cost of broadcasting, firstly, the Z-GFR acts on the election of the dominant nodes. It uses the technique of Z-MPR to divide the local area into several zones and elects a MPR in each zone. This technique reduces the risk of collision by geographically subdividing the nodes that send broadcast packets and collide in radio channel. Secondly, the Z-GFR acts on the transmission of messages. It uses GFR algorithm to separate the whole network into zones and avoids redundant transmission of TC messages between these zones. The zones are calculated while the TC messages are propagated, thus deleting the time delay usually associated with zoning formation. We already implemented and discussed the Z-MPR and GFR in previous works [15,16]. However, this is the first time the two techniques are combined in one algorithm. The Z-GFR decreases the network maintenance cost and frees the channel to help nodes focus on data transmission to achieve maximum delivery of packets with unnecessary delay. Our solution optimizes the selection of MPR, reduces the collision and the loss of packets, and achieves good dissemination of TC messages while eliminating useless transmissions. Both reductions, local and global, represent a huge gain which is reflected on data communication between nodes.

4. OLSR Protocol

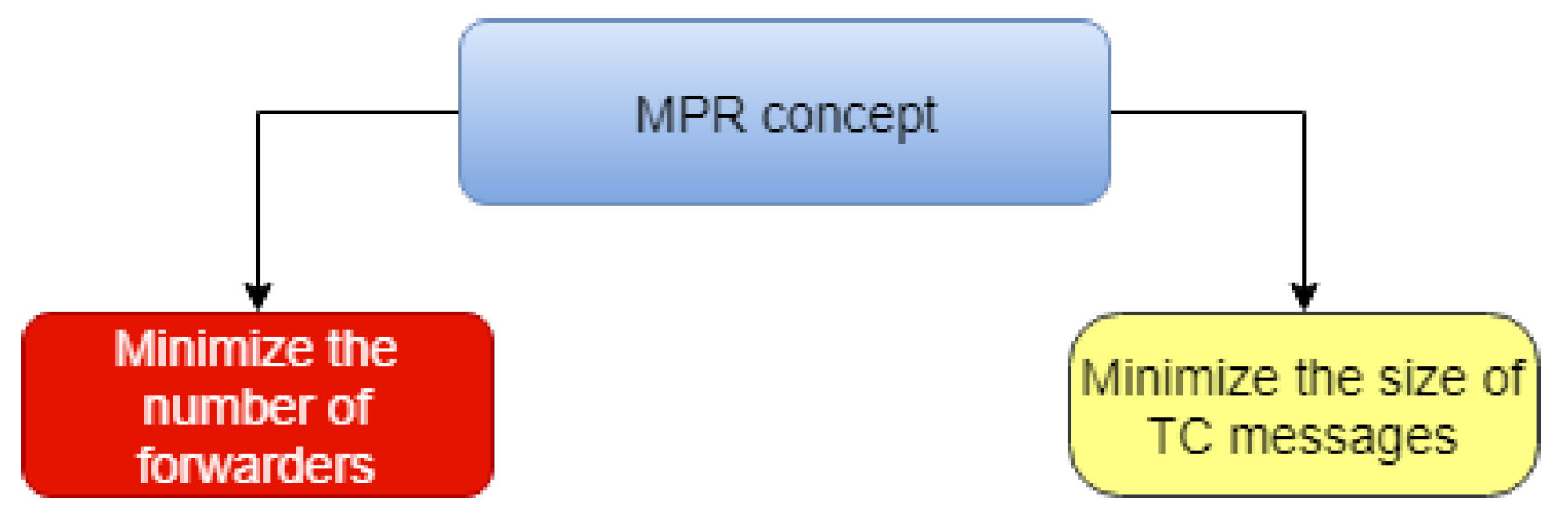

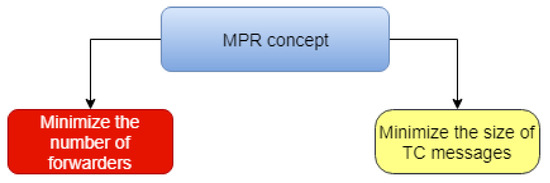

The optimized link state routing protocol [10] is one of the most used protocols in MANETs. It is part of the table-driven (proactive) routing protocols that build the routing tables by periodically exchanging topology control messages. The OLSR has adopted the MPR concept [29] to achieve good dissemination of TC messages. The MPR concept optimizes the overhead, firstly, by selecting the minimum number of nodes to act as forwarders of TC messages. Secondly, only links between MPRs and their selectors are shared to reduce the size of TC messages. Figure 2 shows the principle of the MPR concept. We model the OLSR network as a unit disk graph , where V represents the set of nodes and E the set of symmetric edges. is the signal length of the node u. For simplicity, we consider that signal range R is uniform for all nodes. Two nodes u and v form a symmetric link if and only if they are at distance . The OLSR protocol maintains regularly local information and global information in each node. Neighborhood information is broadcasted via HELLO messages by each node u in the network. The HELLO messages are never forwarded and they serve to discover one-hop and two-hop neighbor sets denoted and , respectively. Every node elects from its neighbors a set of nodes to act as MPRs to forward TC messages. We denote the set of MPRs of a node u as and the set of MPR selectors as . A node u updates its topology information information each time a HELLO or a TC message is received. The topology information on a node u is a directed subgraph of the graph G denoted .

Figure 2.

MPR concept of Optimized Link State Routing protocol.

In this section, we describe the MPR concept of OLSR, especially the MPR selection and the default forwarding rules (DFR) of TC messages.

4.1. The MPR Computation of OLSR

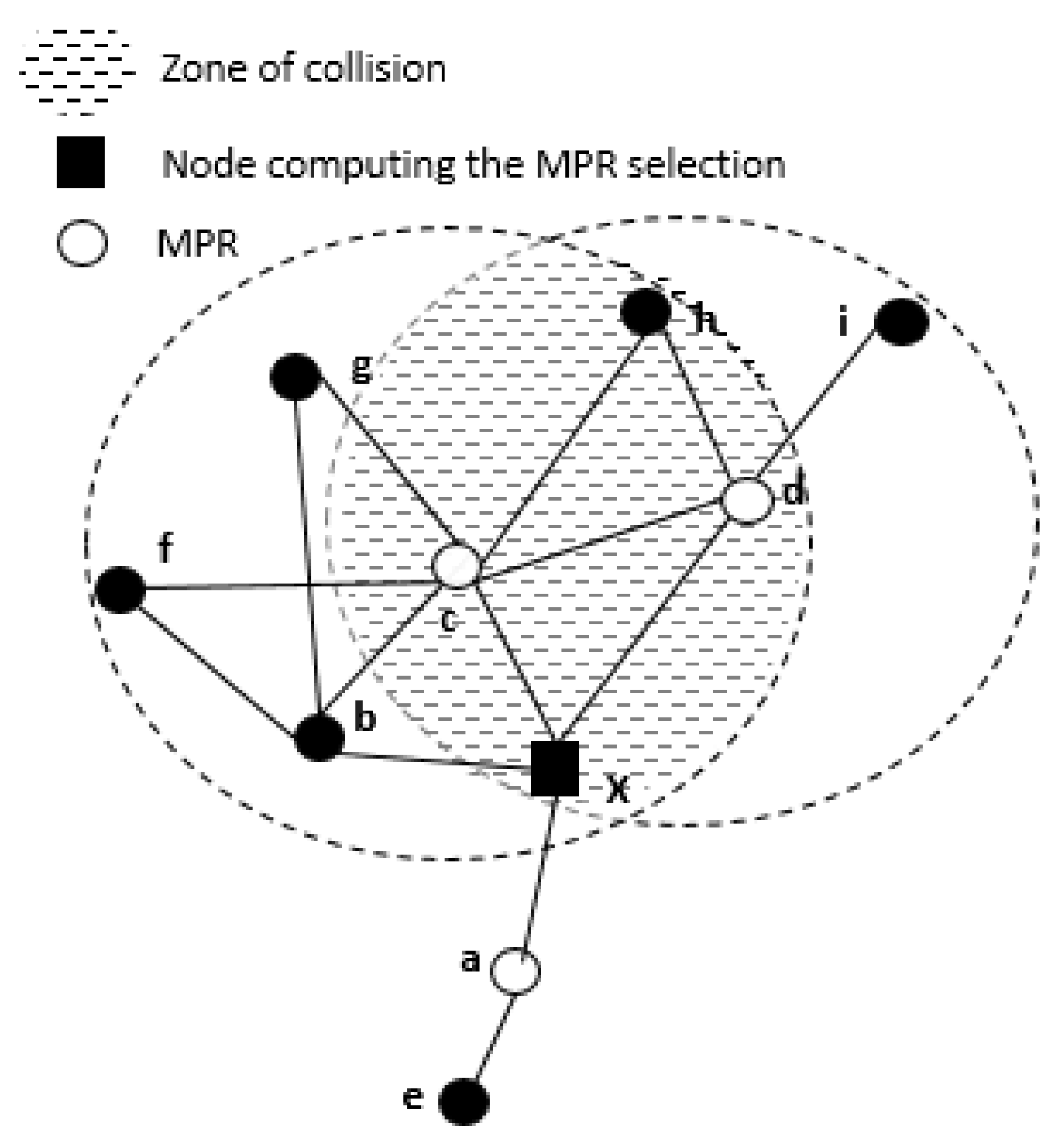

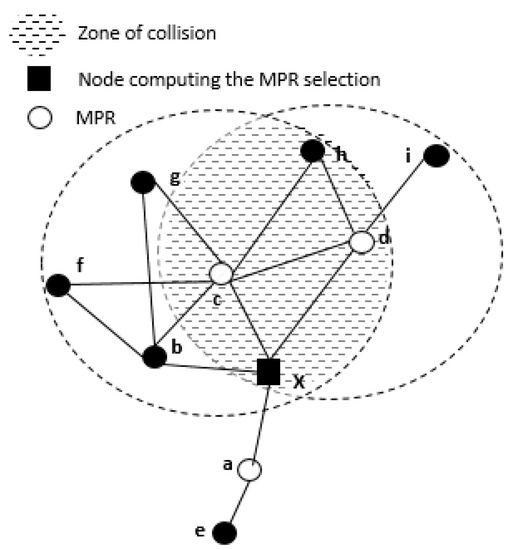

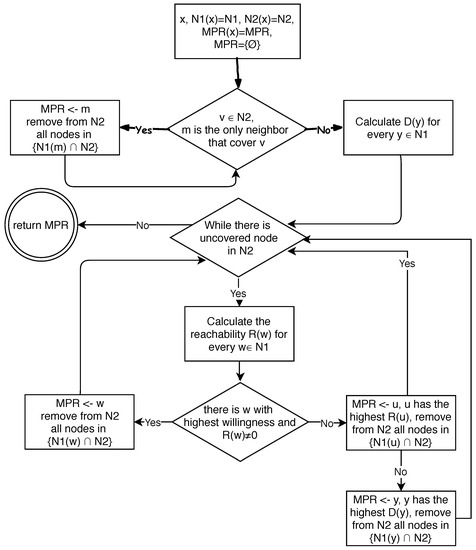

The OLSR exchanges HELLO messages on a regular interval to sense links between nodes, to discover one-hop and two-hop neighbors and to build a local topology. HELLO messages are exchanged in broadcast manner and they are never forwarded to other nodes. A device informs, within the HELLO messages, its adjacent nodes about its links with other nodes. The MPR set is computed every time a HELLO message is received. A node selects among its one-hop neighbors the minimum number of MPRs to cover its two-hop neighbors. After the MPR computation is completed, all the two-hop neighbors are covered. The MPR collection should be as small as possible. The smaller the MPR collection is, the lower the overhead would be [30]. Let us consider the OLSR network presented in Figure 3, and . Figure 4 presents the default MPR computation algorithm of original OLSR on the node x as described in [10].

Figure 3.

MPR computation of original OLSR.

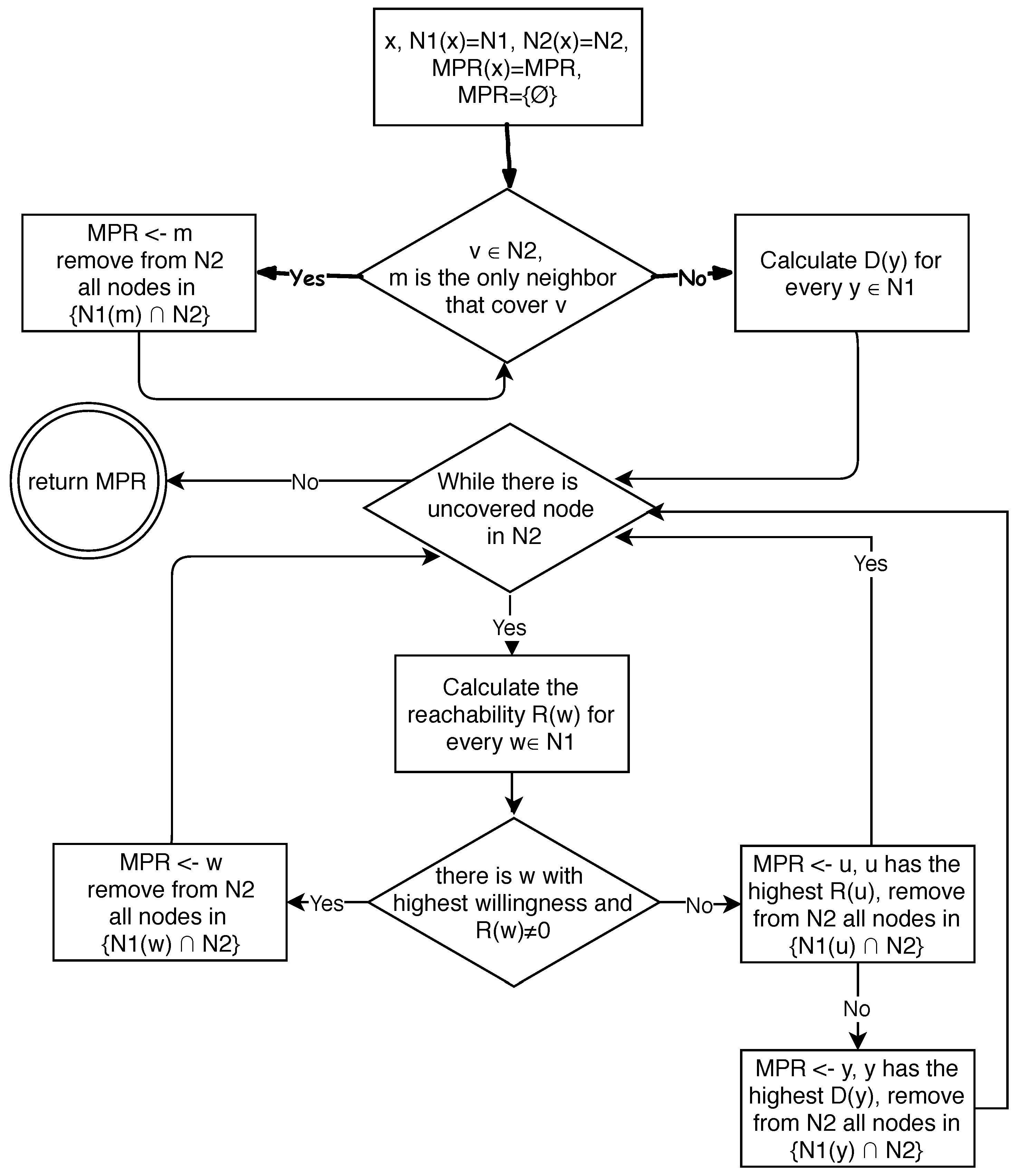

Figure 4.

MPR computation function of original OLSR.

- Input: , , ;

- Start with an MPR set made of all members of with willingness equal to WILL_ALWAYS;

- calculate , where . is defined as the number of nodes ;

- if , m is the only node that covers a node ;

- Remove from all reached nodes by m;

- While there are nodes in which are not covered by at least one node in ;

- (a)

- Calculate for each . R(w) is the number of nodes in which are not yet covered by a node in and are reachable through w;

- (b)

- if w has the highest willingness with ;

- (c)

- In case of multiple choice, , u has the maximum reachability.

- (d)

- In case of multiple nodes providing the same amount of reachability, , where is greater; Remove , the nodes which are now covered by nodes in .

According to the default MPR computation algorithm in Figure 4, x adds a and d to because they are the only nodes connected to e and i, respectively. , , , and . Both b and c have the same reachability. However, . The node x will select node c as MPR and all nodes in will be covered. This MPR set rises the broadcast zone because nodes c and d are close to each other which will increase the collision.

4.2. Default Forwarding Rules of OLSR

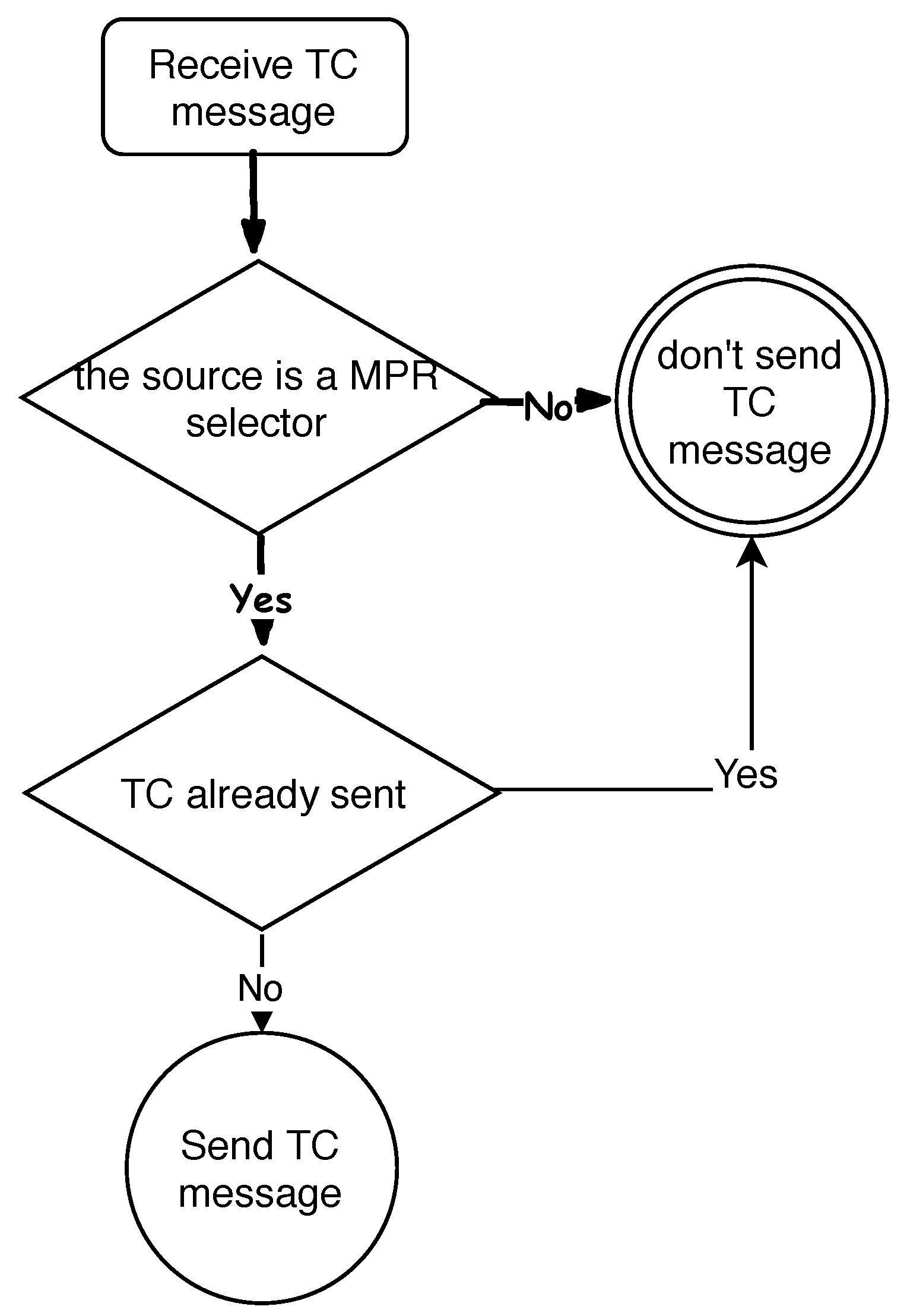

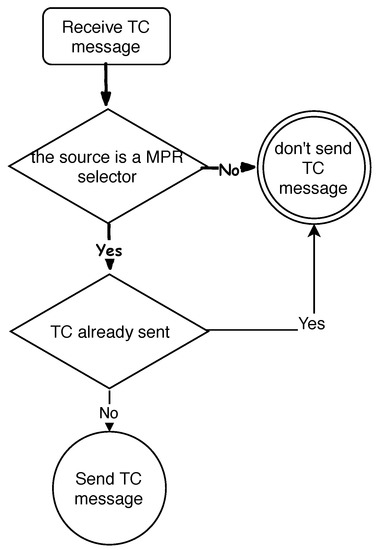

OLSR uses two types of messages to build and maintain the topology over the network: HELLO and TC messages. The HELLO messages discover the neighborhood and sense links between adjacent nodes in order to build the local topology. The TC messages transport the local information to the entire network in order to build global knowledge of the topology. TC messages are generated by MPR nodes every five seconds. They are forwarded from a MPR to another until covering the whole network. When a MPR m broadcasts a message that contains links between itself and its MPR selectors in , all its neighbors in will receive and treat this message, and they will update their routing tables accordingly. However, only a subset of neighbors will forward the : the nodes that are selected as MPRs by m. If u is a MPR and , u rebroadcasts the message towards all nodes in . This flooding mechanism is repeated in order to build global knowledge of the topology. The default forwarding rules of OLSR protocol forward TC messages based on a topology-based heuristic. The DFR take into account only the source of the TC message. Some recipient nodes receive redundant messages since they are neighbors of multiple MPRs. This redundancy consumes sufficient network resources so as to congest the network and decrease the reliability. The default forwarding rules of OLSR are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Default forwarding rules of OLSR.

5. Zone Geographic Forwarding Rules

A node in OLSR selects among its one-hop neighbors the minimum number of MPRs to cover its two-hop neighbors. However, it does not take into account the distribution of MPRs and its impact on network performance. Some MPRs are sometimes side-by-side, which intensifies the collision and decreases the reliability of the network. On the other hand, a node can receive a TC message more than once since it is the neighbor of multiple MPRs. These redundant transmissions consume resources on devices such as energy, smother the network causing more loss of packets, and compromise the reliability of the network.

In this section, we describe the two strategies Z-MPR and GFR, and the change we made to the message header to support both strategies and to implement the Z-GFR.

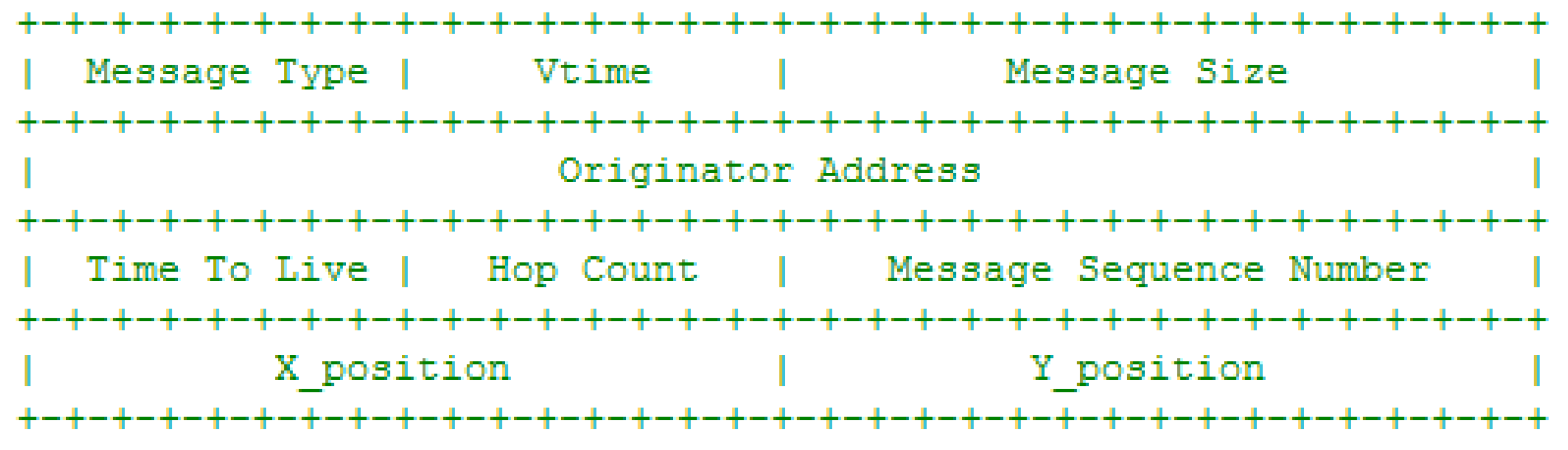

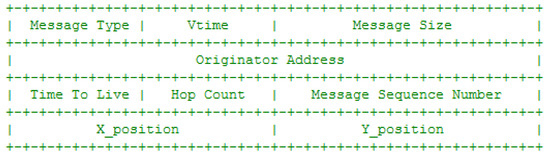

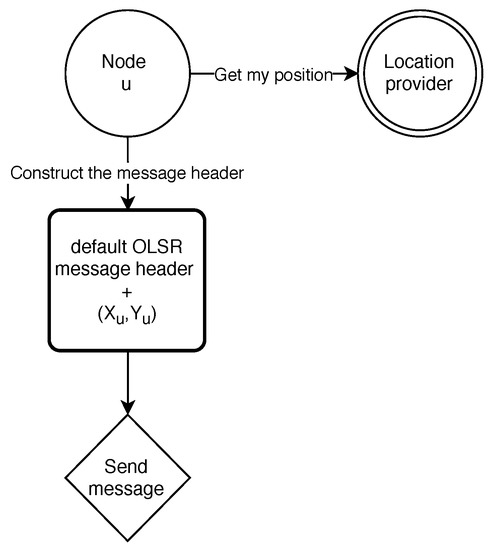

5.1. Extension of the Message Header

Nowadays, the localization is part of the smart devices, which facilitates its exploitation [31]. Many applications are based on location information such as transport, coordination in battlefield, smart home, etc. [32]. Our algorithm assumes that every node u is aware of its position inferred from the location service, while the positions of other nodes are acquired and updated periodically by the topology maintenance mechanism. Our solution acts locally on the surrounding nodes and globally on the entire network. Two fields should be added to the message header to share the location information. Figure 6 shows the new OLSR message header format with the two coordinates X and Y.

Figure 6.

New OLSR message header format.

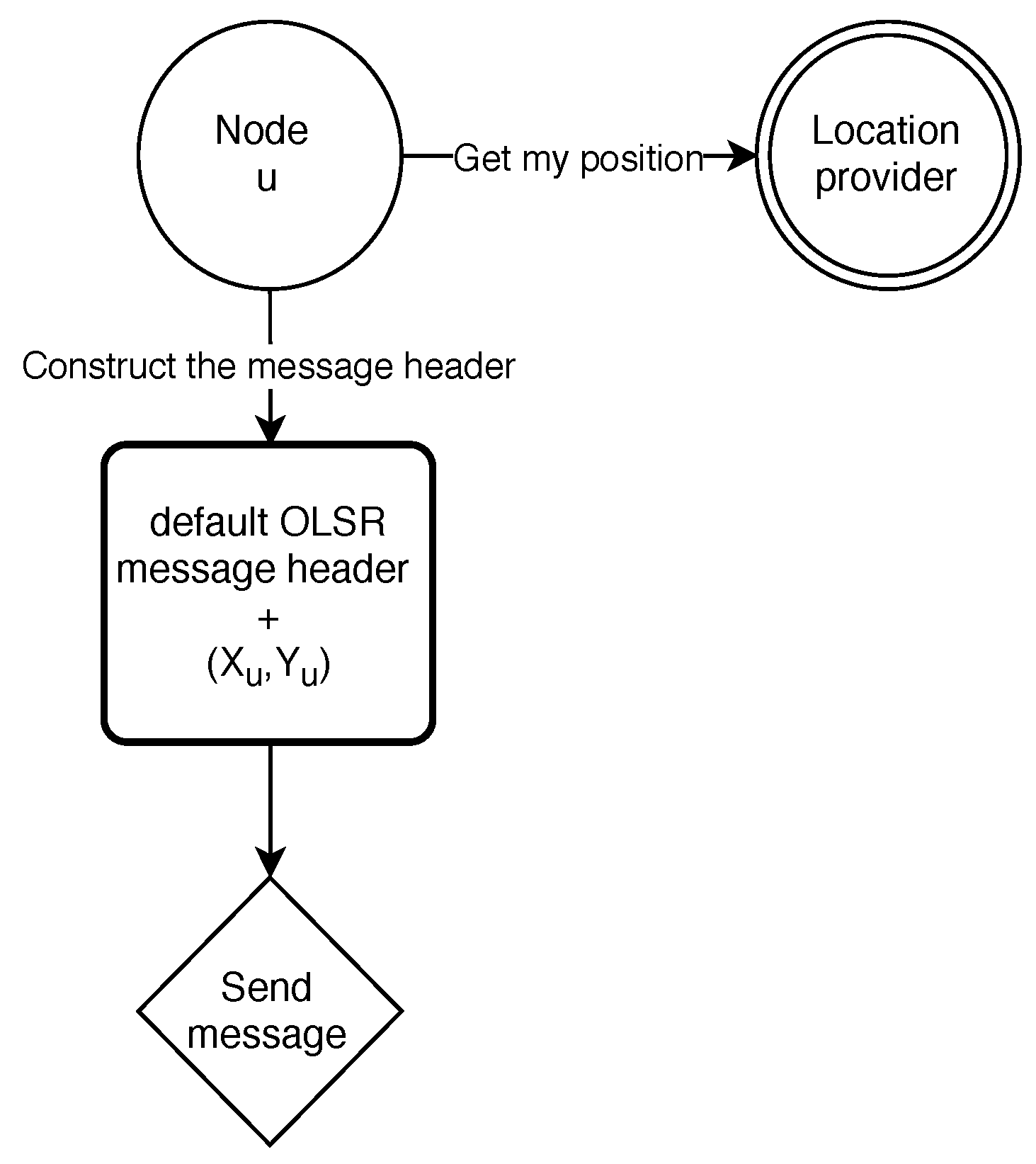

When a node u is ready to send an OLSR message, a HELLO or TC message, it contacts the location service to obtain its position , as shown in Figure 7. Then, it introduces it to the message header. Upon receiving an OLSR message, a node maintains a table of positions of all its surrounding nodes and positions of all MPRs in the network. This geographic information is used to put in place our algorithm.

Figure 7.

Location service in OLSR.

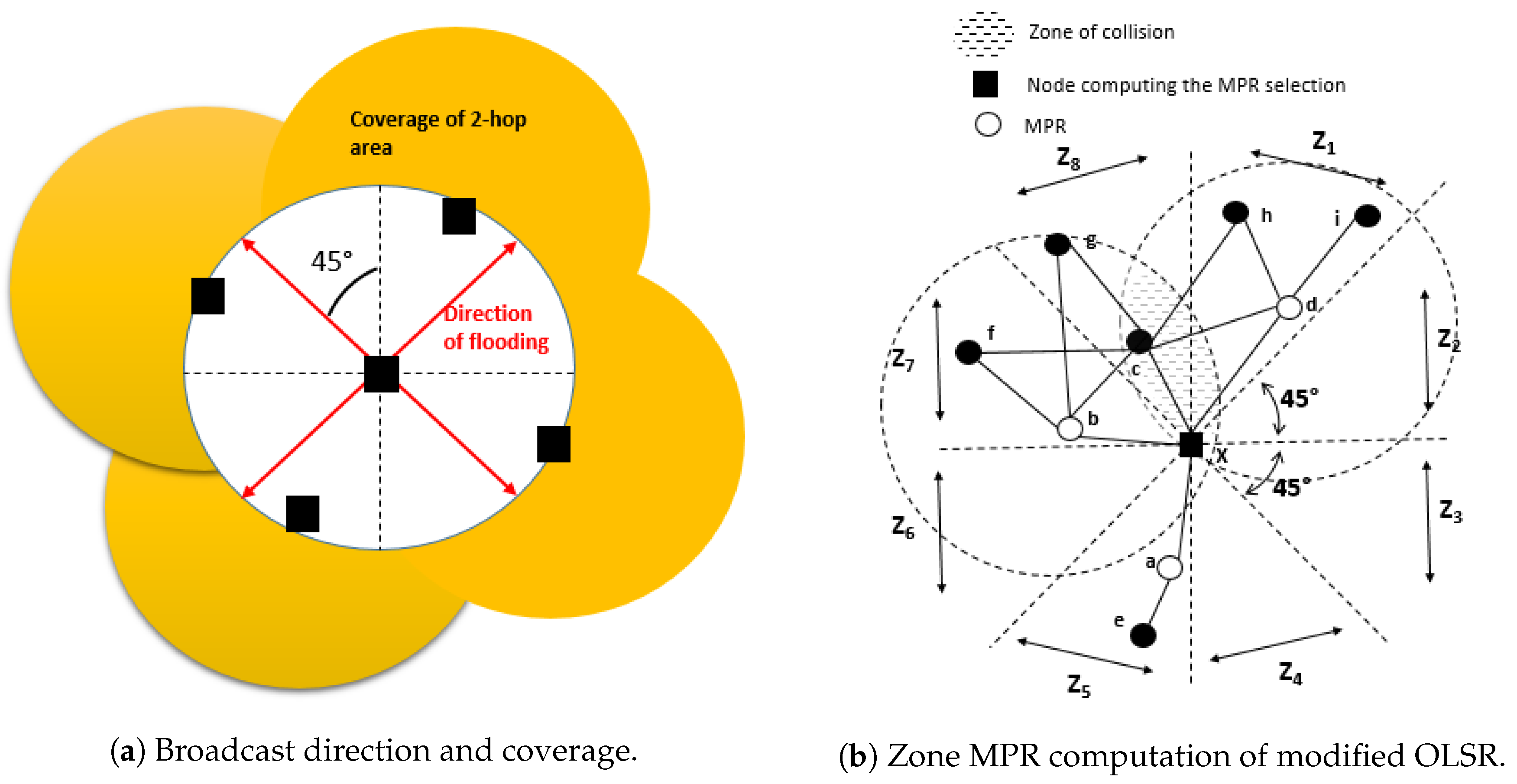

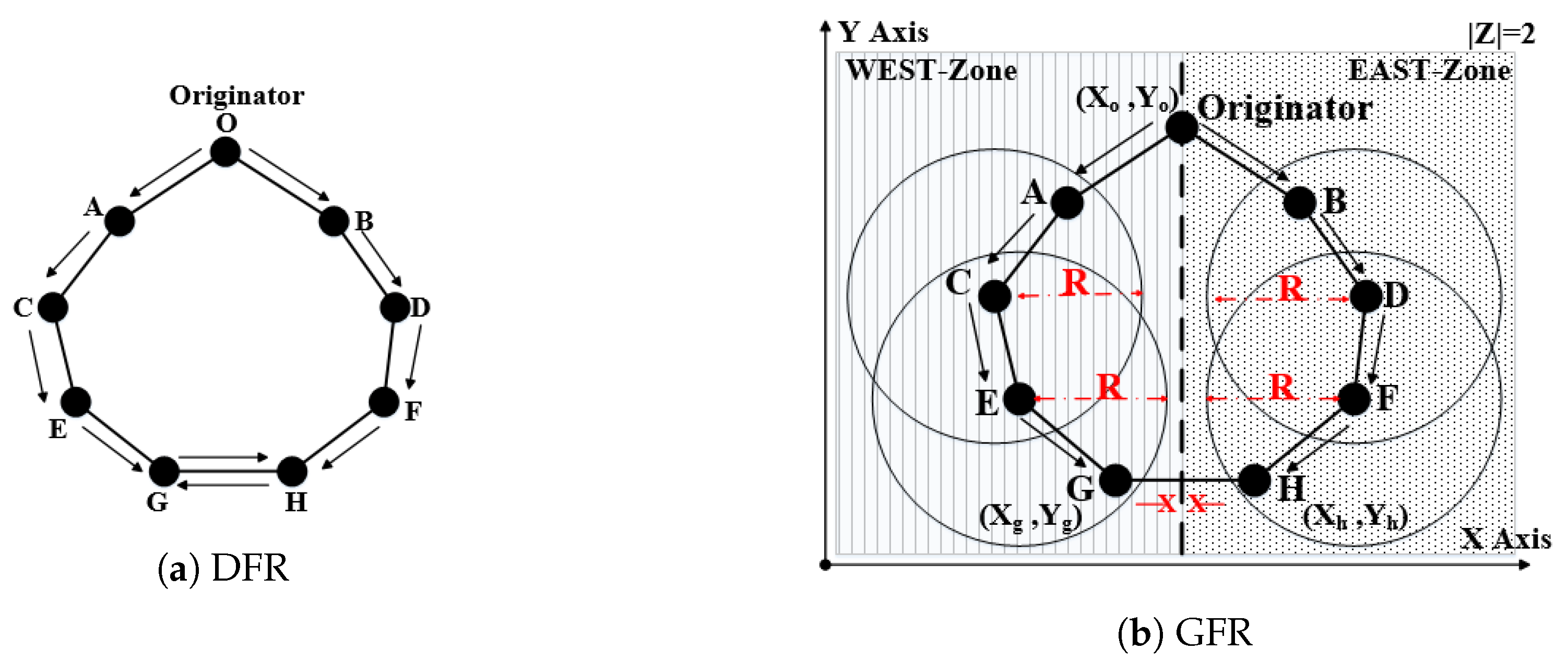

5.2. First Strategy: Acting on Nodes: Z-MPR Computation

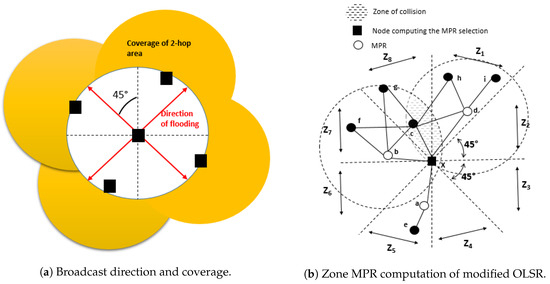

The original MPR selection heuristic is based on the reachability of the maximum number of two-hop neighbors [29]. However, it does not take into account the MPRs layout. Selecting close MPRs lowers the network efficiency due to collision and loss of packets. To support many simultaneous broadcast transmissions without interference, our solution selects dispersive MPRs based on their reachability and their positions. When a node x computes the MPR selection, it divides the neighborhood into eight zones of equal size. Each zone forms a 45-degree angle with the axes of the system of origin , as shown in Figure 8b. This choice is explained by the degree of coverage. With odd zones of 45-degree angles, if the MPR nodes are well placed, we can cover all the neighborhood of the node x and maximize the coverage of the two-hop areas as shown in Figure 8a. With angles less than 45 degrees, the zones tend to get closer, which increases the density of MPR and the size of broadcast zones. With large angles, we find many MPRs in the same zone and it becomes difficult to elect dispersive dominant nodes because the zones cover a large part of the neighborhood of the node x. The node x proceeds as follows.

Figure 8.

First strategy: Acting on nodes.

- First, x changes the current plan to a new Cartesian coordinate of origin x, by deducing its coordinates from the position of all nodes in . The new coordinates of x are and the coordinates of a node are and .

- Then, x determines the zone of every neighbor within the new Cartesian coordinate system. Four cases are possible:

- and

- –

- if , u belongs to

- –

- if , u belongs to

- –

- if , u is on the border of and

- and

- –

- if , u belongs to

- –

- if , u belongs to

- –

- if , u is on the border of and

- and

- –

- if , u belongs to

- –

- if , u belongs to

- –

- if , u is on the border of and

- and

- –

- if , u belongs to

- –

- if , u belongs to

- –

- if , u is on the border of and

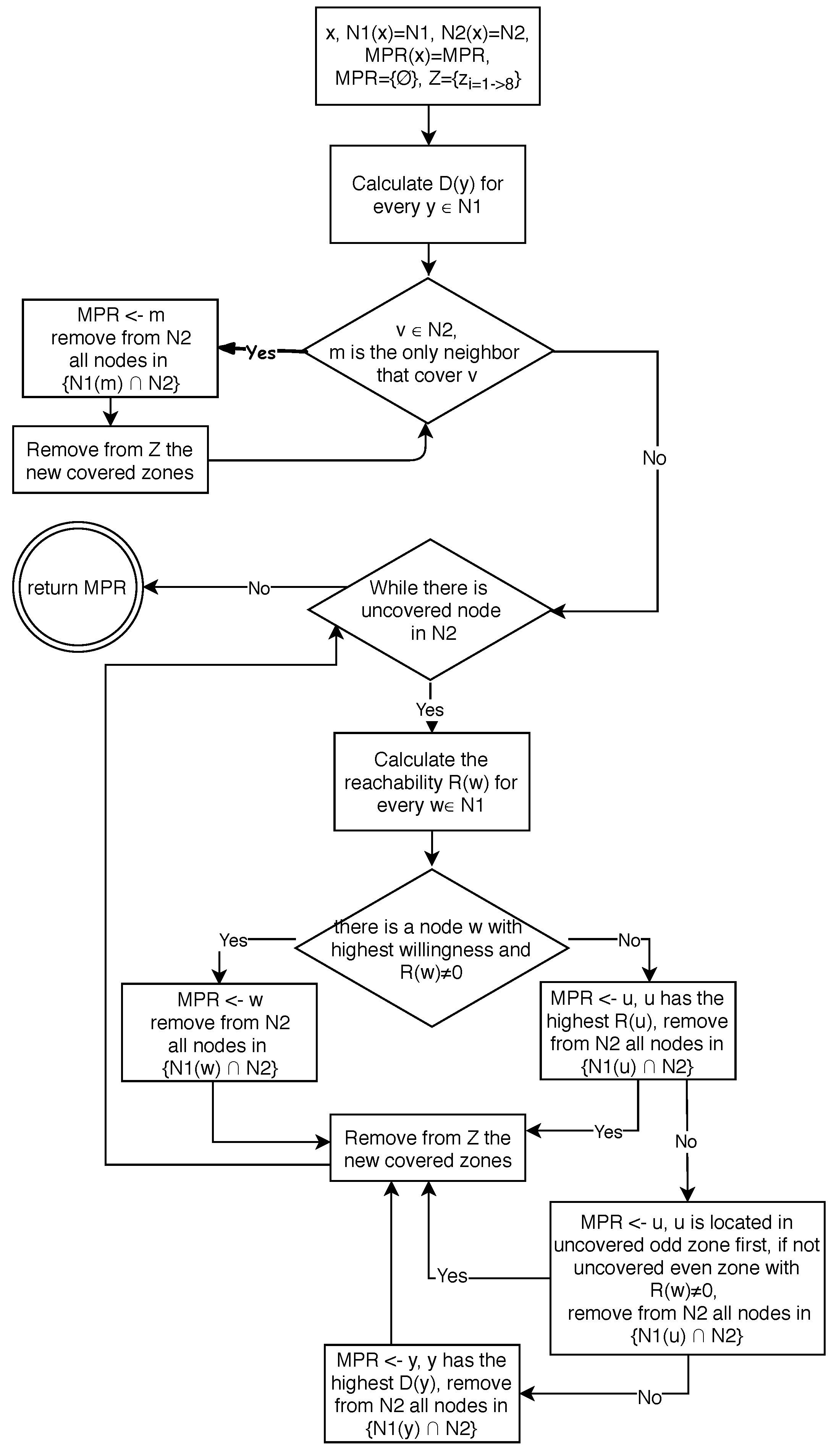

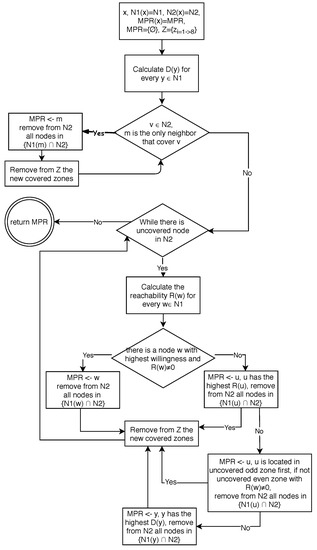

- Finally, the node x elects dispersive MPRs by selecting a node in each zone prioritizing odd zones to keep them away from each other. The new MPR computation algorithm is detailed below and summarized in Figure 9:

Figure 9. Zone MPR computation of modified OLSR.

Figure 9. Zone MPR computation of modified OLSR.- Input: , , ; ; ;

- Start with an MPR set made of all members of with willingness equal to WILL_ALWAYS;

- calculate , where . is defined as the number of nodes ;

- if , m is the only node that covers a node ;

- Remove from all reached nodes by m;

- remove from Z the covered zone where m is located;

- While there are nodes in which are not covered by at least one node in ;

- (a)

- Calculate for each . R(w) is the number of nodes in which are not yet covered by a node in and are reachable through w;

- (b)

- if w has the highest willingness with ;

- (c)

- Remove from Z the new covered zone;

- (d)

- In case of multiple choice, , u has the maximum reachability. Remove from Z the new covered zones;

- (e)

- In case of multiple choice, , u is located in uncovered odd zone first, if not u is in an uncovered even zone with . Remove from Z the new covered zone.

- (f)

- In case of multiple choice, , where is greater; Remove from the nodes which are now covered by nodes in .

- (g)

- Remove from Z the new covered zone.

In the network presented in Figure 8b, both nodes b and c provide the same reachability. However, node b is located in an odd zone and c is in an even zone close to the MPR d. Node x will select b instead of c even if is greater. This selection will help to reduce the zone of collision in the radio channel, decrease the loss of packets and make the network more reliable.

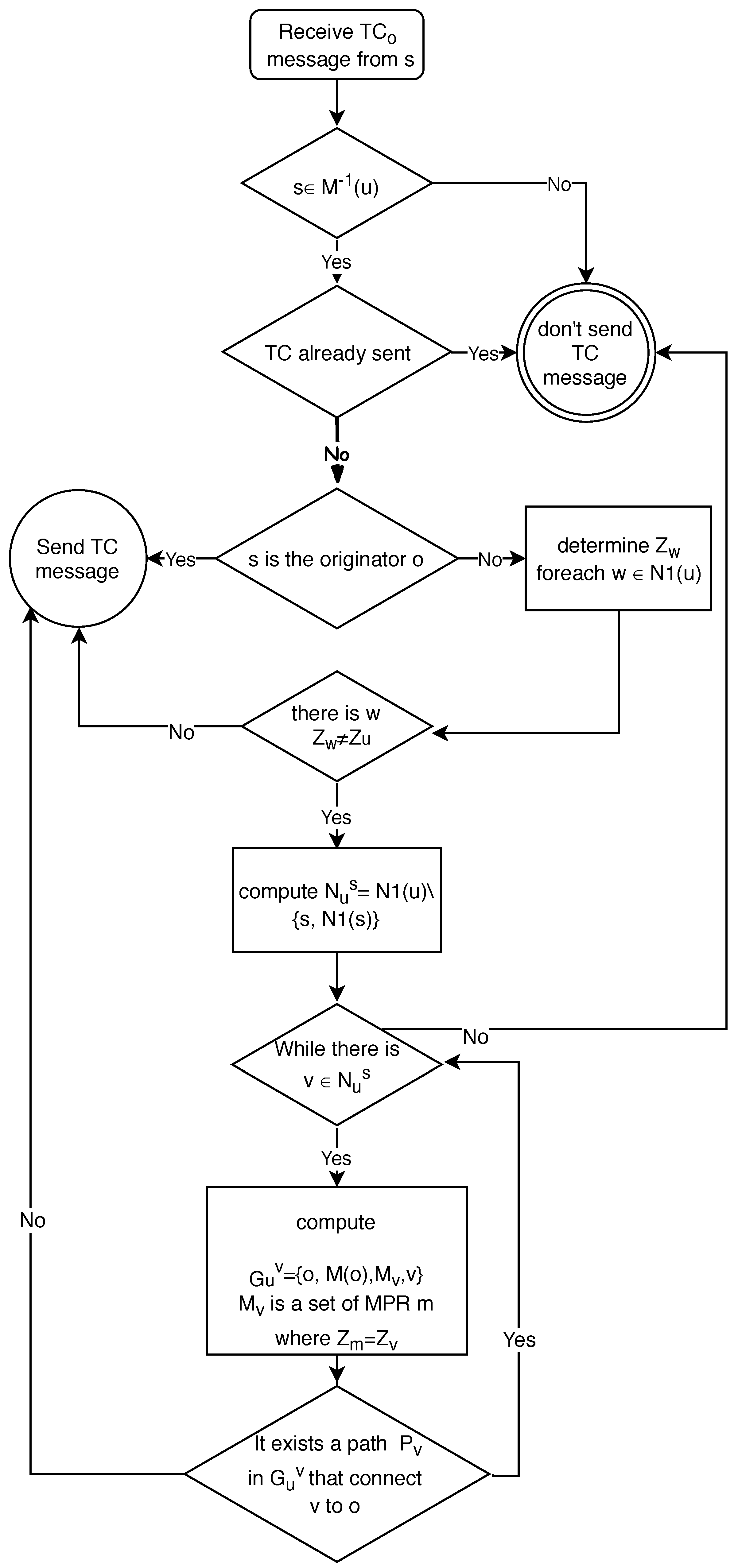

5.3. Second Strategy: Acting on Transmissions: Geographic Forwarding Rules

The MPR concept guarantees that a shortest path exists between every two nodes in the network. However, the default forwarding technique, summarized in Figure 5, takes into consideration the source of the message without caring about the destination nodes. Nodes may receive the same TC message more than once, which lowers the network efficiency. Considering the destination nodes in the flooding process may help to reduce the redundant transmissions and enhance the reliability of the network.

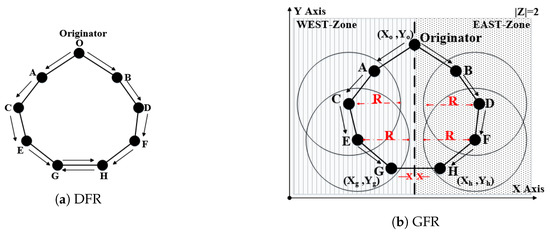

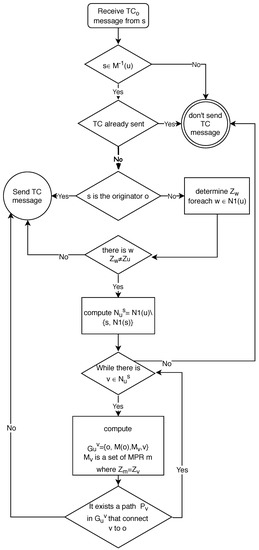

In the network illustrated in Figure 10a, both h and g will rebroadcast the message generated by node o. Both of them will receive the message twice. These redundant retransmissions consume resources on all nodes in . The geographic forwarding rules, illustrated in Figure 11, use the location information of nodes to divide the network into virtual zones and delete useless transmissions between these zones. Upon receiving the message, node h divides the network based on the position of the originator o into two vertical zones. The border line goes through the position of node o and it is perpendicular to the x-axis. Figure 10b shows the virtual zones and the border line inferred from the coordinates introduced in the message. Node h computes and according to the Cartesian coordinate system of origin . h locates itself and g in the east and west zones, respectively. Node h detects that node g is located in another zone and tries to avoid the transmission of the . Node h checks the topology G’ to find another path formed by MPRs located in the same zone as g, which connects node g to the originator o. Node h computes the path and abstains from rebroadcasting . The same procedure applies on node g. It computes the path and it abstains from rebroadcasting the . Thus, the GFR avoids redundant transmissions between zones and saves resources such as bandwidth and delay, which makes the network more reliable. There are as many groups of zone as there are TC messages circulating in the network. Every group is related to the position of the MPR at the time it sends the TC message. Algorithm 1 describes the the geographic forwarding rules in OLSR.

Figure 10.

Difference between DFR and GFR.

Figure 11.

Geographic forwarding rules of OLSR.

| Algorithm 1 Geographic forwarding rules of modified OLSR. |

|

6. Results

We implemented our algorithm in Network Simulator NS-3 [33] that contains the native OLSR protocol module. A series of simulation experiments was conducted to analyze and compare the performance of four algorithms: OLSR, Z-MPR, GFR and Z-GFR. We compared our proposals with OLSR protocol to measure the improvement compared to standards in term of network performance. Comparing the Z-GFR with other techniques permits knowing the best algorithm. However, it does not permit measuring the percentage of enhancement compared to well known protocols. We used bonnmotion [34] to generate the same random behavior of nodes for all simulations for realistic comparison.

The simulations consisted of different densities of nodes moving randomly in a fixed area of 1000 m × 1000 m. This increased the number of devices in specific regions and helped us to study and compare the impact of the density on different routing protocols. Moreover, with the increase of the number of nodes, the broadcasting was also increased, affecting the performance of the network negatively, which gave us the opportunity to prove the effectiveness of Z-GFR by reducing the amount of useless broadcast messages. The simulations were run under the same conditions and network configuration. Table 1 summarizes the simulations’ parameters. We started 10 udp communications at the second 50th to measure the impact of Z-GFR on data communication between nodes. The twenty nodes exchanged udp packets of size 200 bytes at rate 256 kbps until the second 90th. We used flow monitor tracing [35] to extract the network metrics. We compared the four algorithms in terms of the number of generated, received and transmitted TC messages; the number of packets exchanged in the network; and the number of dropped packets in the physical layer of nodes. For the udp sockets, we measured the throughput, the loss of packets, the packet delivery ratio (pdr) (e.g., the proportion of packets successfully received) and the delay.

Table 1.

Simulations’ parameters.

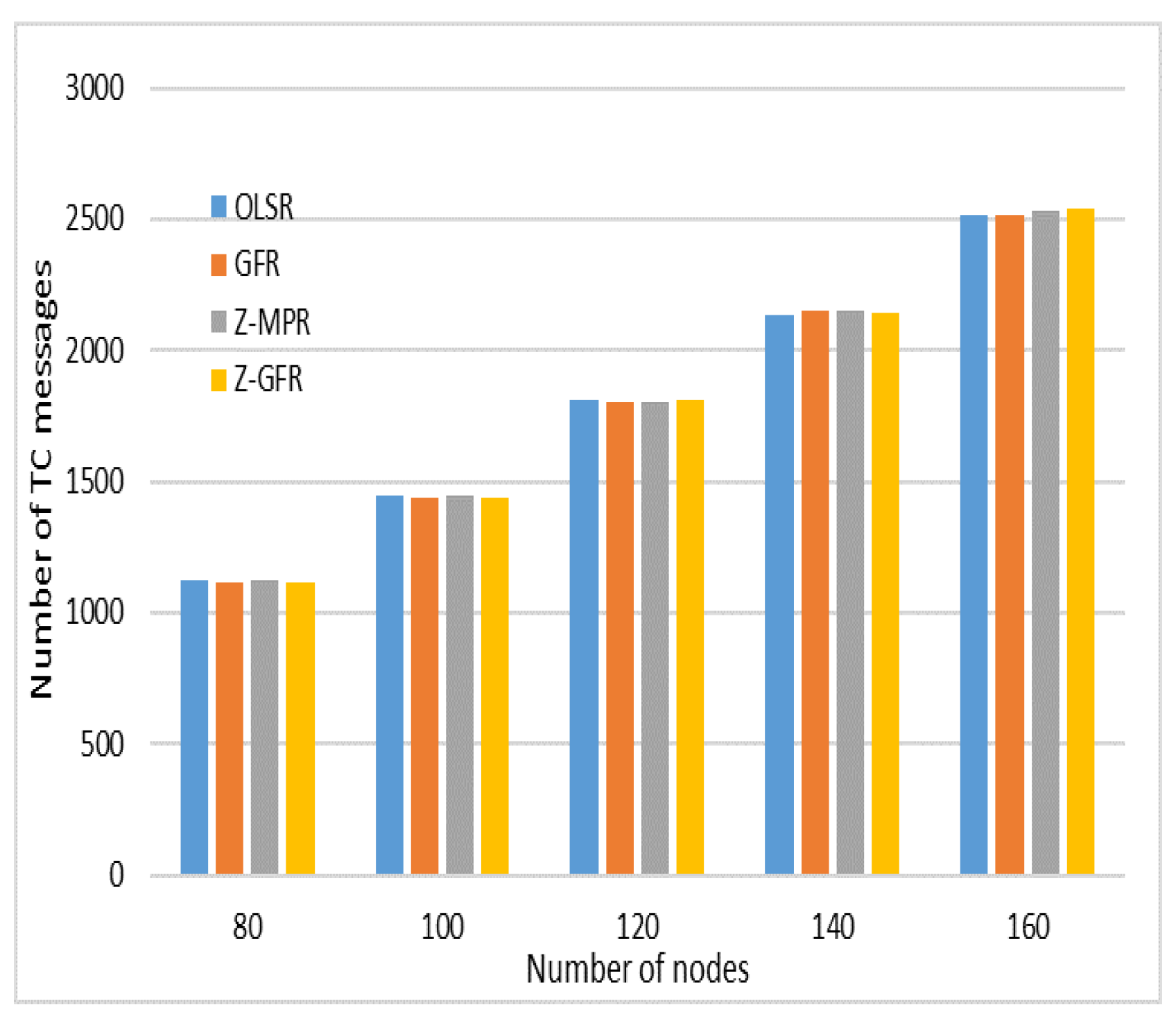

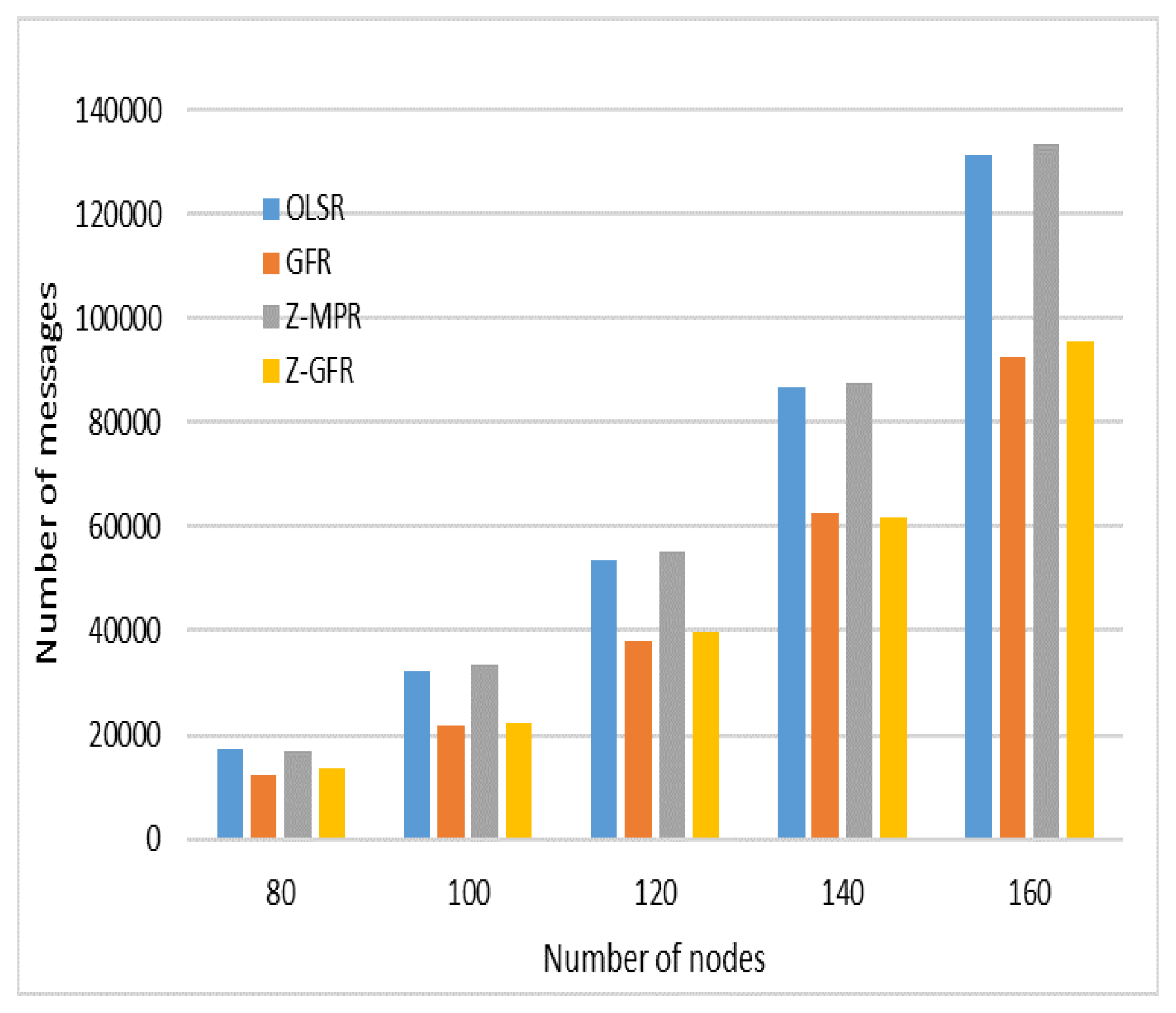

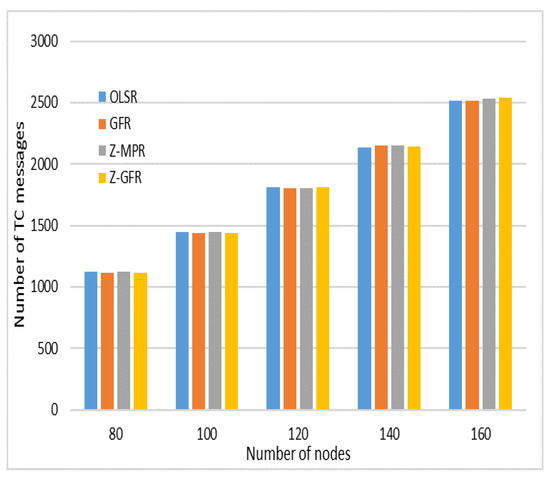

Figure 12 shows the number of generated TC messages by all the MPRs in the network. The number of MPRs remains the same for the four protocols, which allows generating approximately the same number of TC messages as the original OLSR. However, Z-MPR, GFR and Z-GFR affect the retransmission and the reception of TC messages since they affect the structure of MPRs or reduce the number of transmissions.

Figure 12.

Number of generated TC messages.

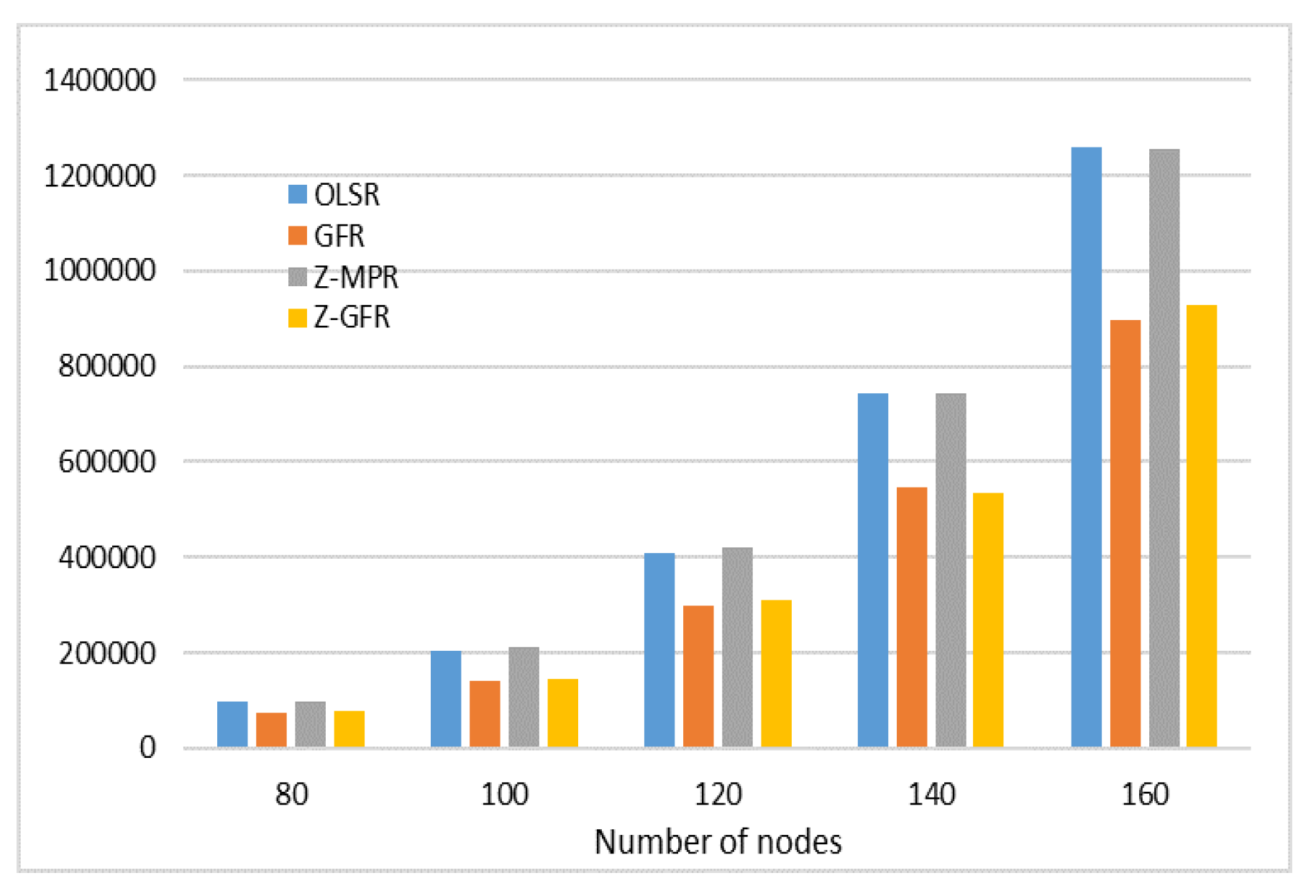

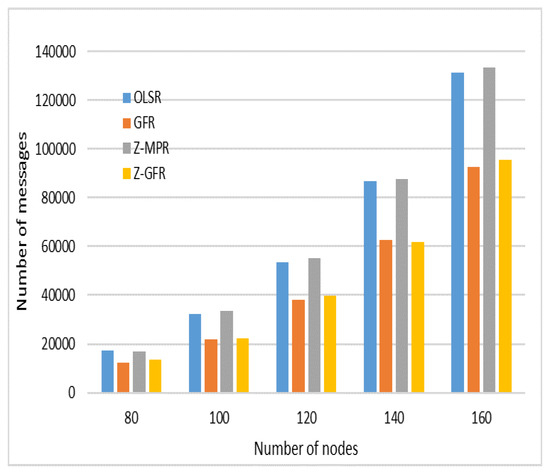

Figure 13 shows the number of retransmissions of TC messages by all the MPRs. We remark that the number of transmissions of TC messages in Z-MPR differs slightly from that of the original OLSR. This is explained by the fact that Z-MPR modifies the MPR layout, which changes the density of each MPR and allows rebroadcasting TC messages freely without interferences. The GFR and Z-GFR decrease, as expected, the number of retransmissions by deleting the useless ones. The gain in terms of number of retransmissions is increases as the network becomes denser. The two protocols minimize approximately 28% of retransmissions. However, we remark that the two protocols have a small difference of number of retransmissions due to the MPR distribution near the border line of the two zones, which affects the search for the alternative path P. These reductions of retransmissions help to free the channel for data transmission between nodes.

Figure 13.

Number of retransmissions of TC messages.

The influence of the three modified protocols on the number of retransmissions impacts the reception of TC messages. Figure 14 shows the number of receptions of TC messages by all nodes in the network. The difference in terms of retransmissions between OLSR and Z-MPR as well as GFR and Z-GFR are reflected on the reception of TC messages. The two reductions represent a huge gain to reduce the protocol overhead and to enhance the performance of the network.

Figure 14.

Number of receptions of TC messages.

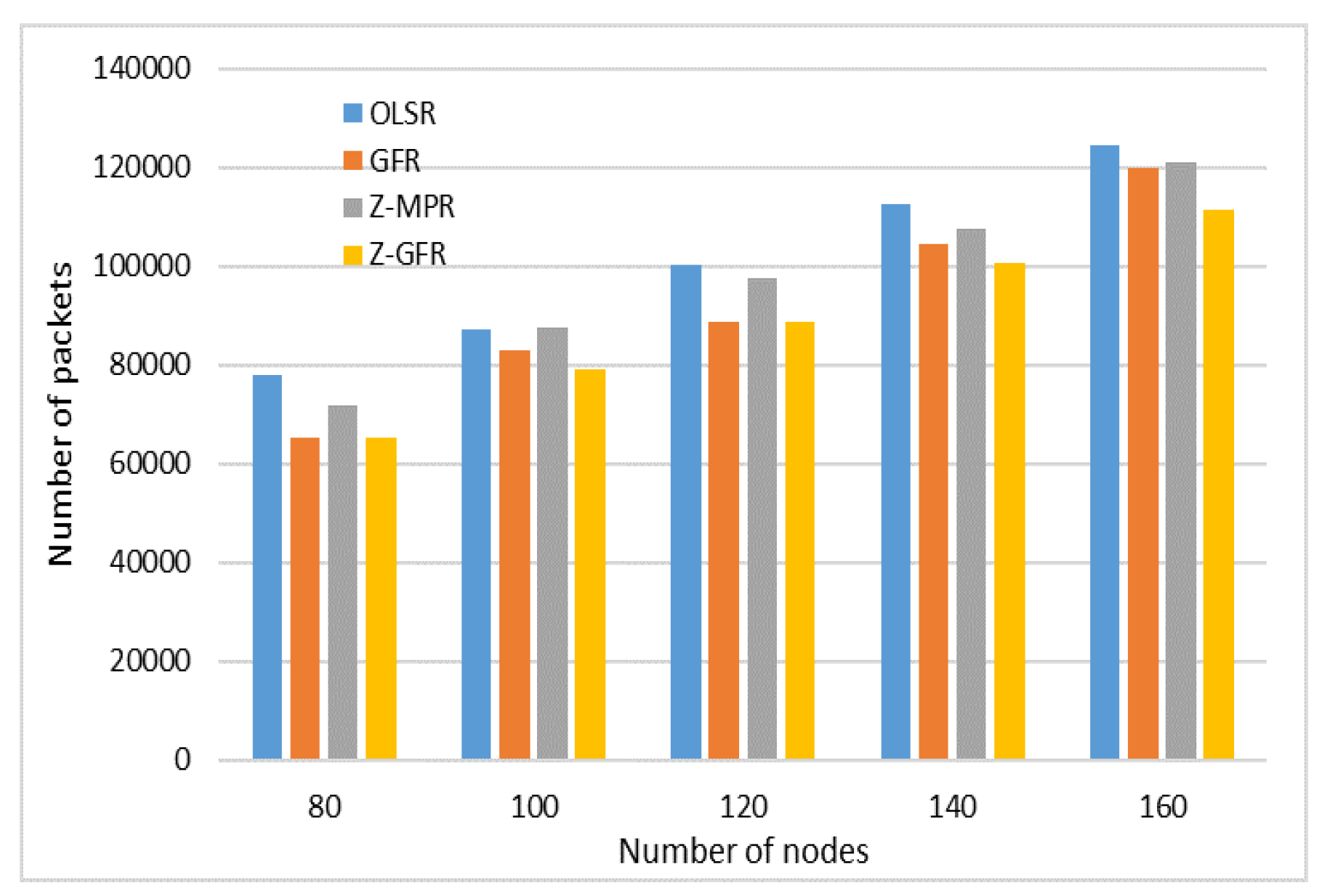

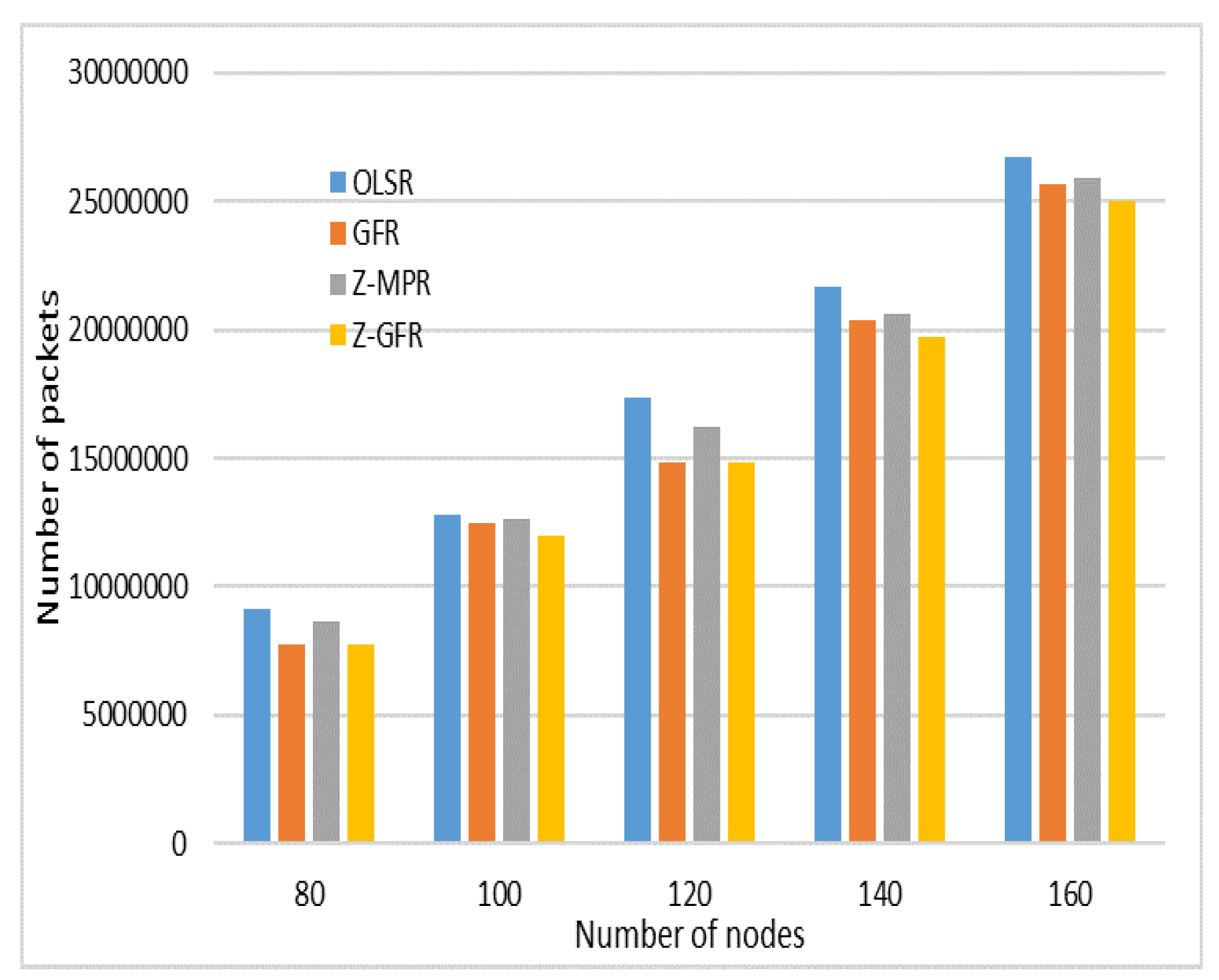

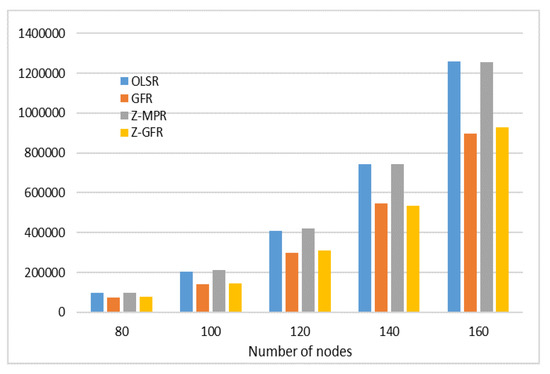

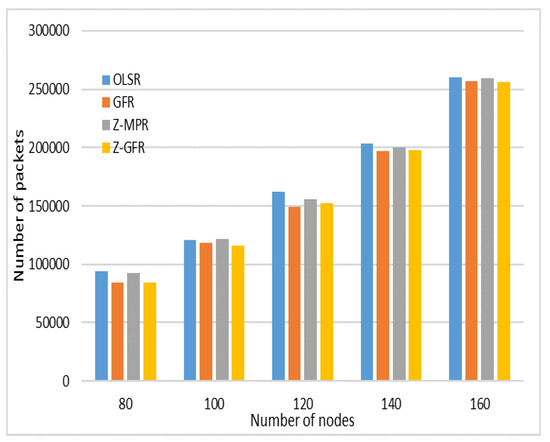

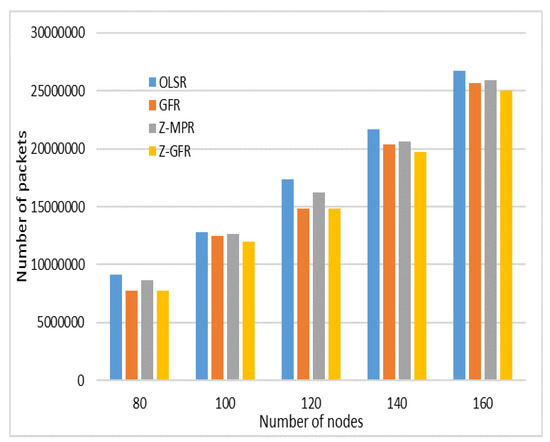

Figure 15 and Figure 16 show, respectively, the sum of packets transmitted and received at the MAC layers of nodes. The packets shown here concern the UDP sockets and the protocol overhead. We notice that GFR and Z-GFR perform better than Z-MPR. They reduce a considerable number of useless transmissions between the two zones. Z-MPR impacts the packets positively and performs better than OLSR due to the reduction of collision. This is explain by the fact that nodes do not have to resend the dropped packets, which increases the successful receptions. We reduced the number of messages by approximately 30%. However, the number of transmitted packets did not have the same reduction, because the TC messages increase. Adding the coordinates of the originator to the header of OLSR increases the size of the messages. However, the size of cancelled transmissions exceeds the size of all the extensions of the messages. Despite this increase, we reduced the number of packets exchanged in the network compared to the other protocols.

Figure 15.

Number of packets transmitted to the MAC layers of nodes.

Figure 16.

Total number of packets received at the MAC layers of nodes.

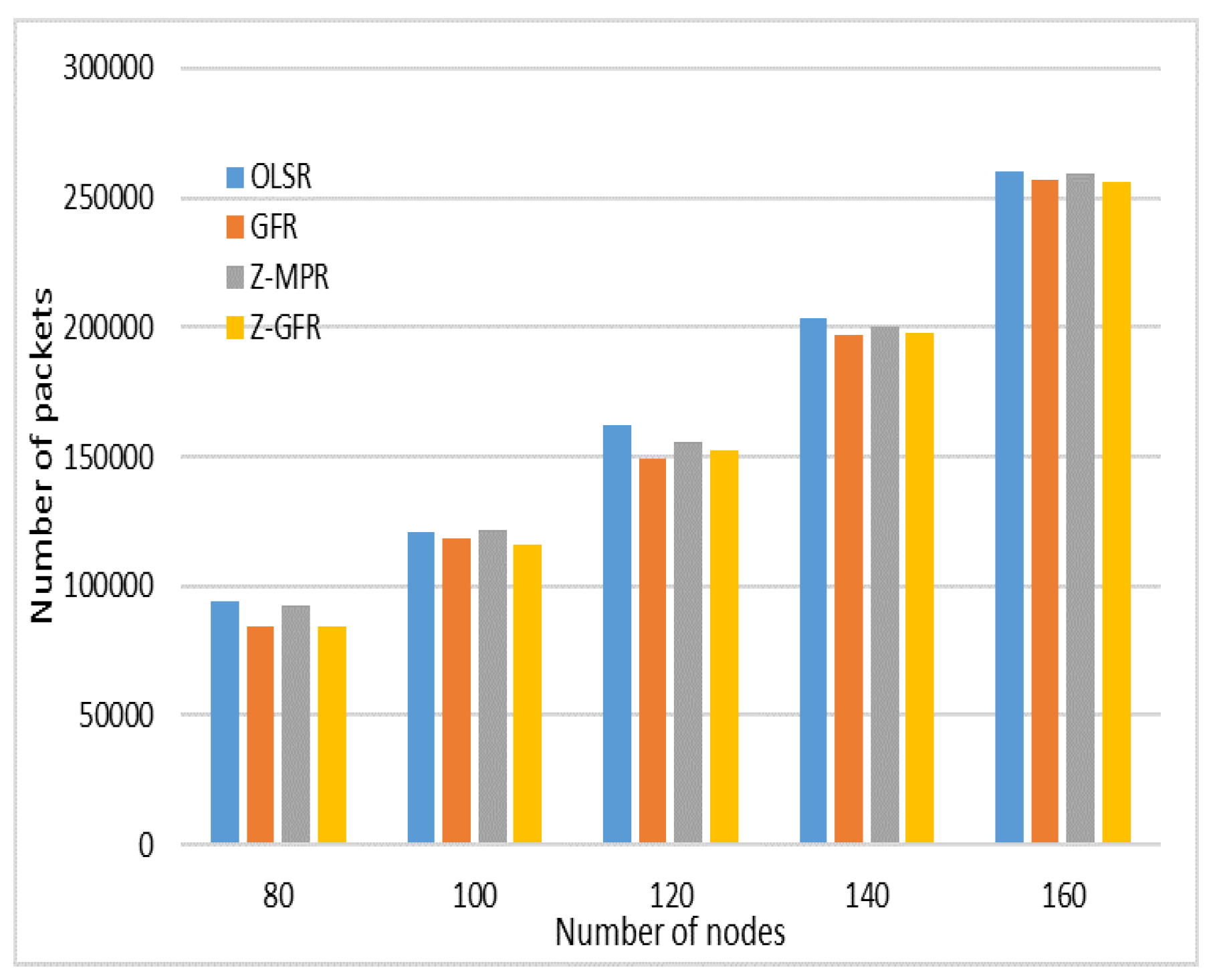

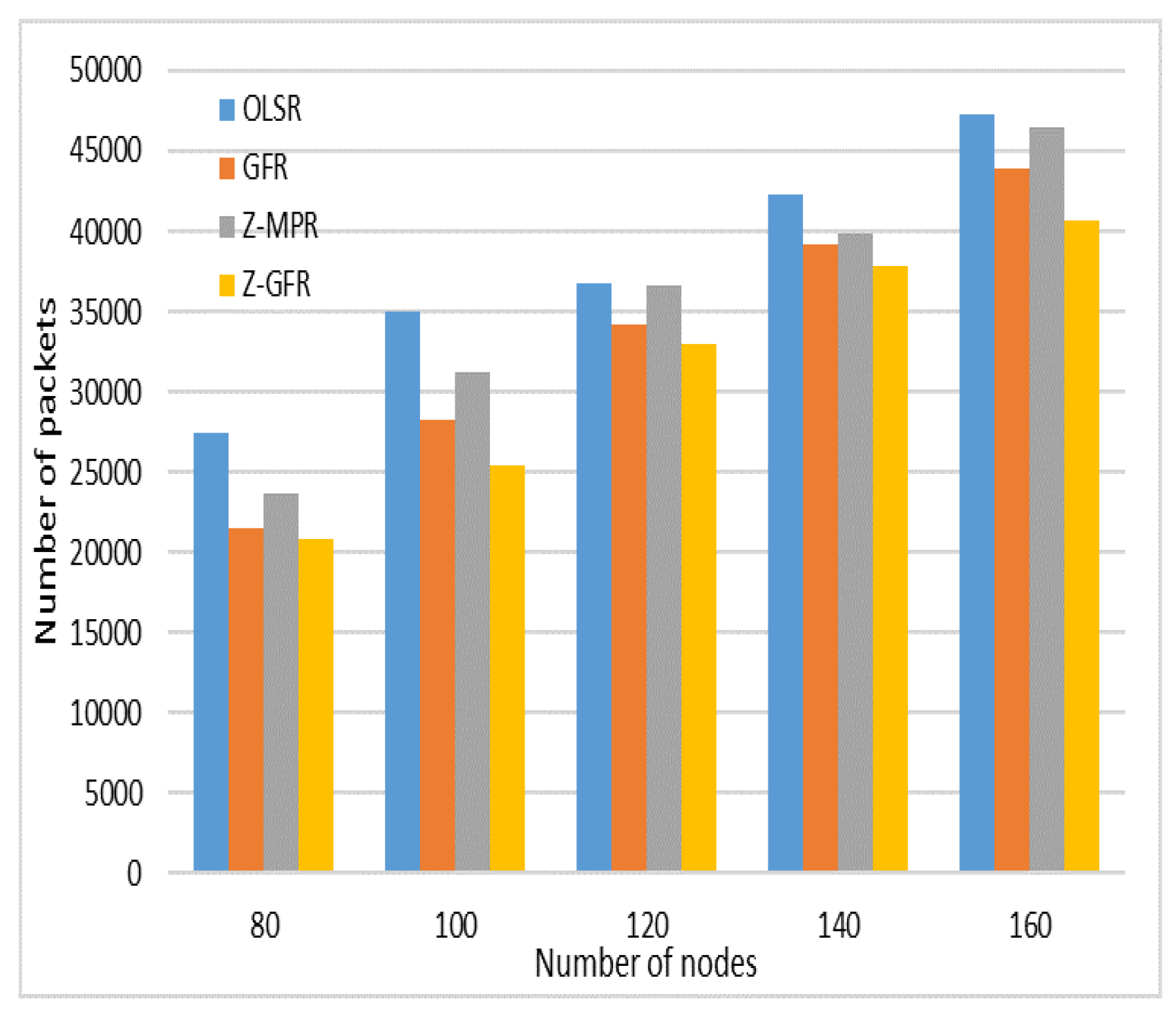

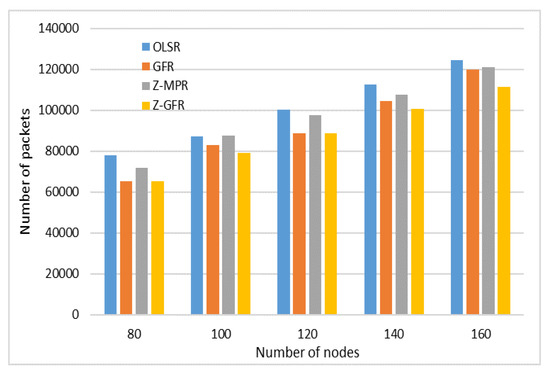

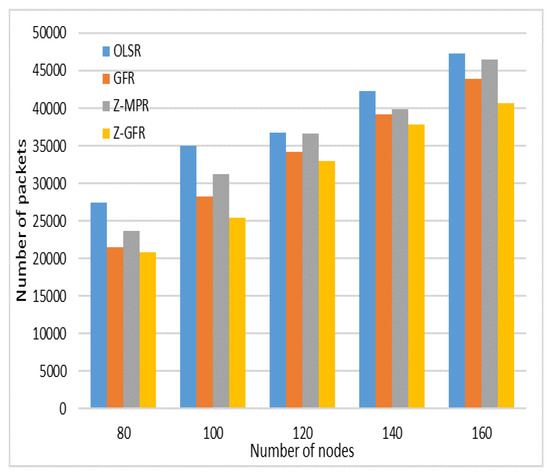

Nodes in mobile communications share the same radio channel. Reducing the protocol overhead may free the channel and decrease the loss of packets. Figure 17 shows the dropped packets at the physical layers of nodes. We notice that the three modified protocols drop fewer packets than the original OLSR. Z-GFR uses a reduced number of packets at the MAC layer, which allows our protocol to free the channel and avoid collisions more than the GFR. As a result, nodes remove few packets compared to other protocols. Z-MPR removes fewer packets than OLSR because it decreases the collision at the level of MPR nodes. This helps broadcast messages to be exchanged fluently. However, decreasing the useless TC messages in GFR decreases the packets needed to transfer them, which allows the GFR to drop fewer packets than Z-MPR.

Figure 17.

Total dropped packets at the physical layers of nodes.

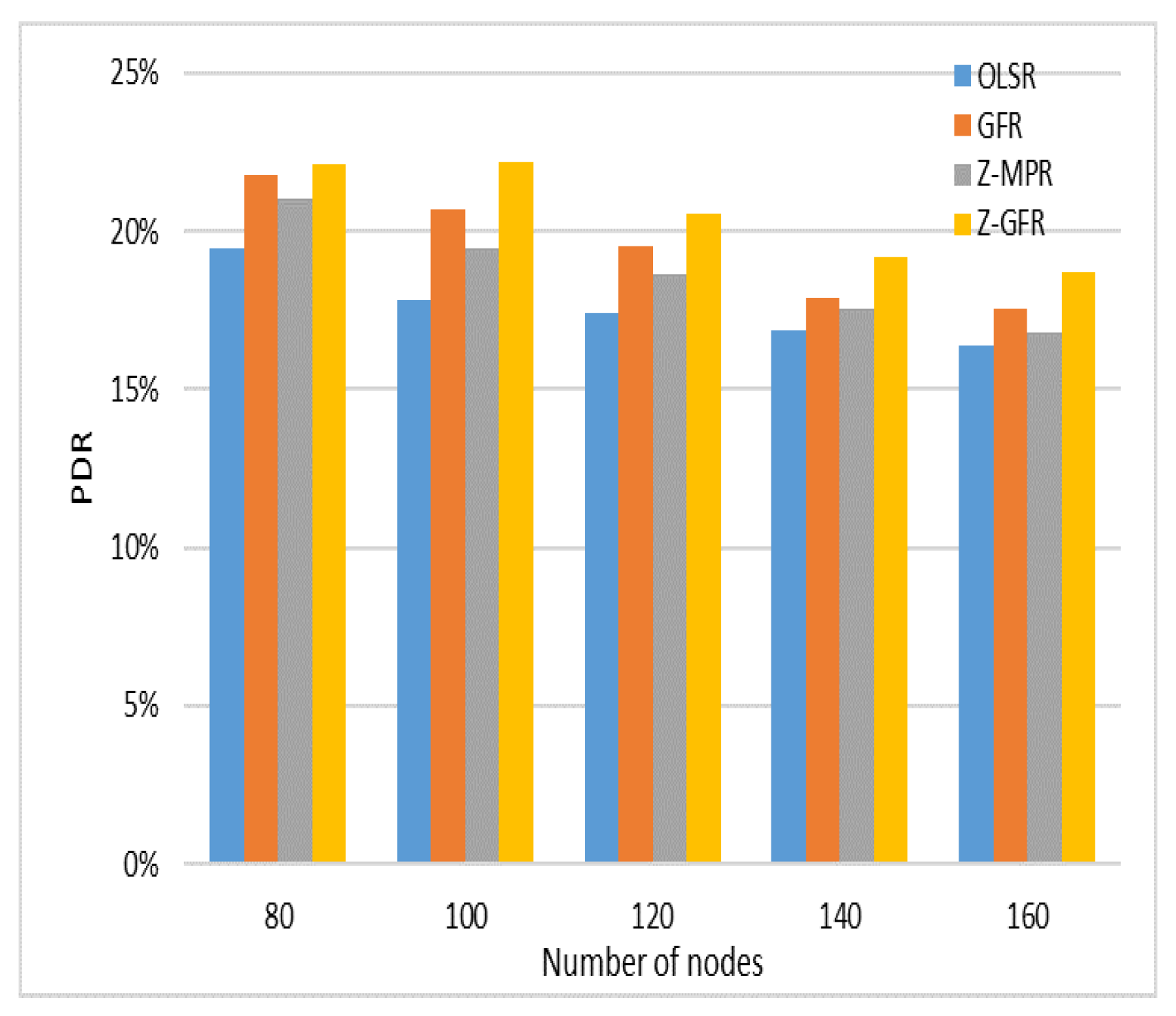

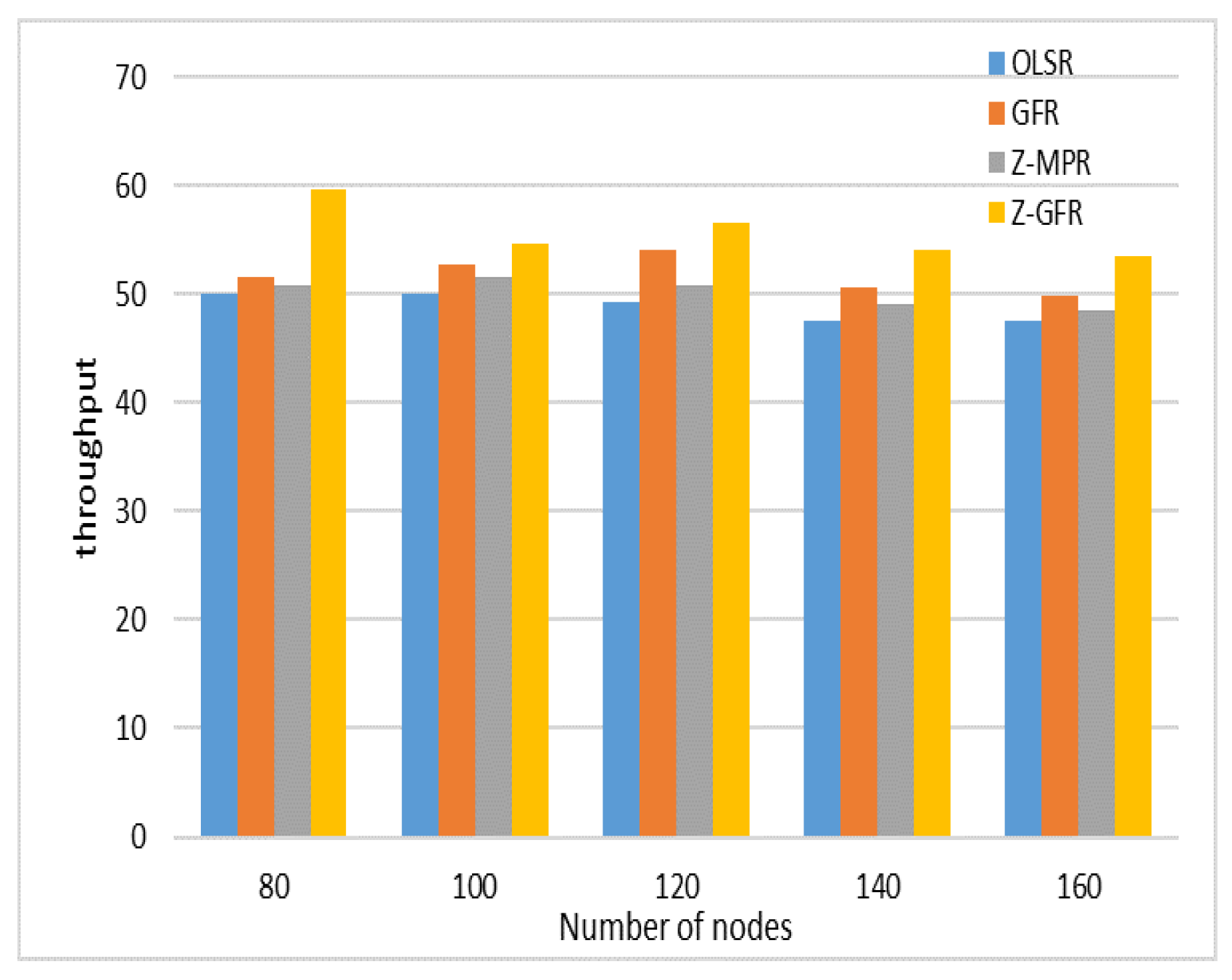

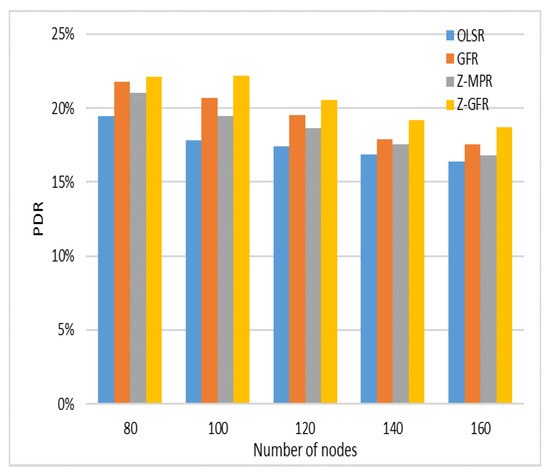

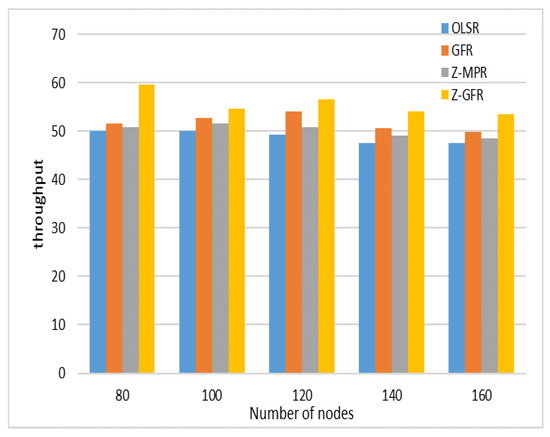

Reducing the number of exchnaged packets in the radio channel impacts obviously the exchange of data packets. Figure 18 and Figure 19 show respectively the loss of packets and PDR of the UDP sockets. We remark that Z-GFR drops less data packets than the other protocols because it frees the channel. The reduced overhead permits to applications to transfer more data than the OLSR protocol. The GFR reduces considerable useless transmissions, offers fluent network and outperforms the Z-MPR in terms of PDR and lost packets. One of the consequences of the increase of the PDR and the reduction of lost packets is the increase of data transfer rate. Figure 20 shows the sum of throughput of the ten udp sockets. It proves that our solution Z-GFR exchanges packets at high rate because the protocol overhead has decreased to the maximum. Z-GFR offers 14%, 11% and 8% of bandwidth better than OLSR, Z-MPR and GFR, respectively. This helps nodes to exchange more data than the other protocols.

Figure 18.

Loss of packets of the udp sockets.

Figure 19.

pdr of the udp sockets.

Figure 20.

Throughput of the udp sockets.

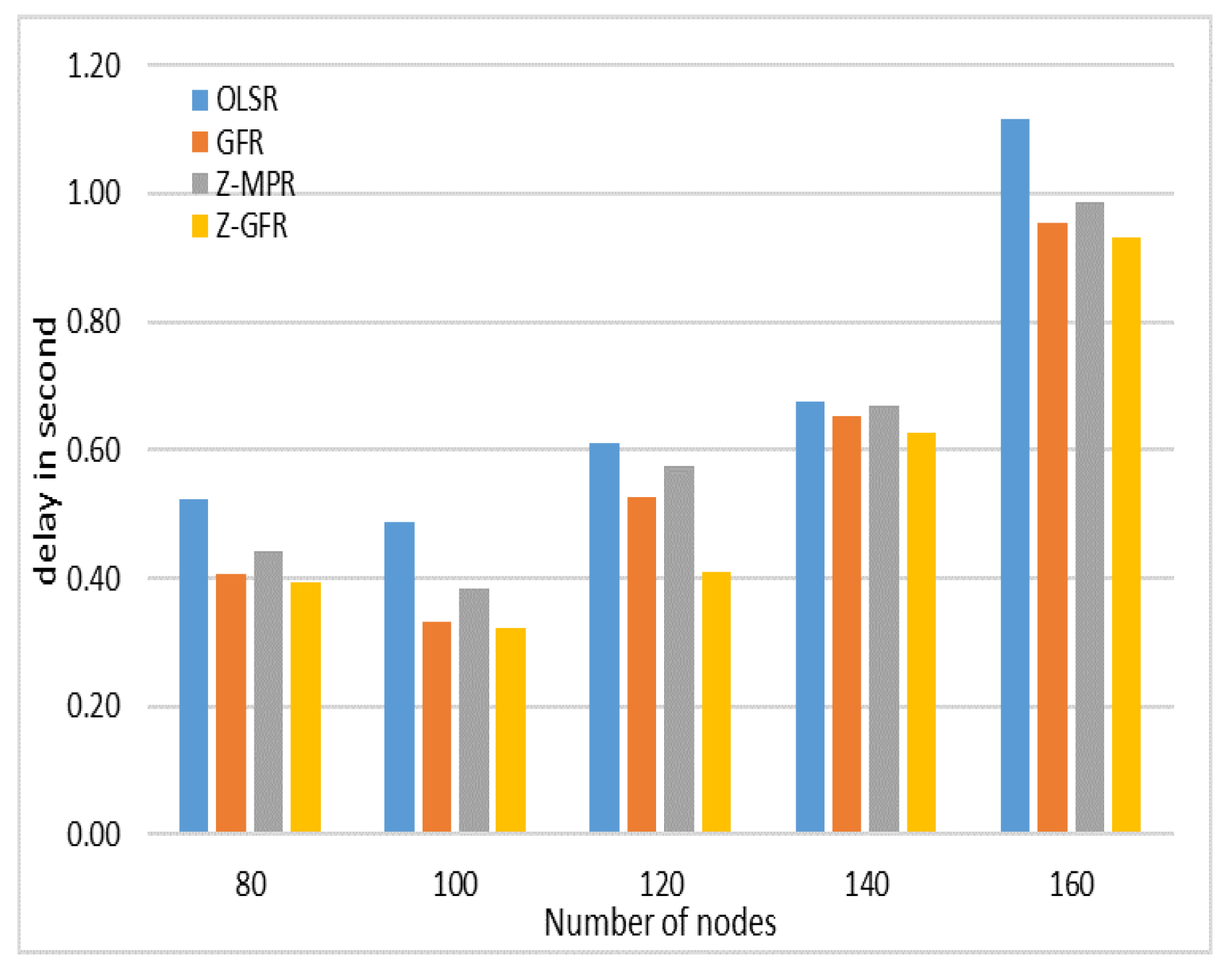

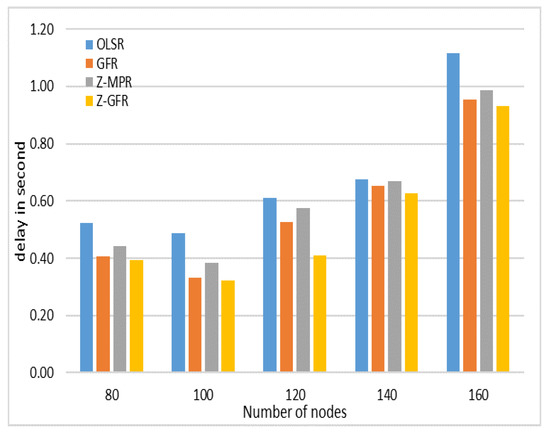

Figure 21 shows the end-to-end delay that the data spent between source and destination. The more reliable is the network, the better is the delay. Our solution Z-GFR reduces the number of TC messages and lost packets, therefore it decreases the latency and makes the network more reliable. It performs better than the other protocols, which makes it suitable for real time applications such as voice over ip and video streaming.

Figure 21.

Delay of the udp sockets.

7. Conclusions

With the proliferation of localization techniques, many studies have been carried out to reduce the side effects of mobile routing protocols, allowing several new protocols to see the day. They have proven that using geographic information can help further improve routing protocols. In this study, we used two strategies to optimize the overhead in mobile communication with location information of nodes. The first strategy, the Z-MPR technique, divides locally the neighborhood into zones and elects dominant nodes in different zones to separate them from each other in order to reduce the collision. The second strategy, the GFR technique, divides the whole network into propagation zones and avoids useless transmissions between them. Both techniques coexist together and operate in the same routing algorithm in a distributed manner that we call Z-GFR. We implemented our solution in the context of OLSR and showed by simulations that our technique Z-GFR outperforms the OLSR protocol and two other zoning techniques. Z-GFR has reduced considerably the traffic overhead of OLSR and has increased the throughput, making the network more reliable and suitable for real-time application such as voice over ip or online gaming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; Formal analysis, M.S.; Software, H.B.; Supervision, A.H.; Writing—original draft, M.S.; and Writing—review and editing, M.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OLSR | Optimized Link State Routing |

| AODV | Ad hoc On-demand Distance Vector |

| RR | Route Request |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GFR | Geographic Forwarding Rules |

| MPR | Multipoint Relay |

| Z-MPR | Zone Multipoint Relay |

| Z-GFR | Zone Geographic Forwarding Rules |

| MANET | Mobile Ad hoc Network |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

References

- Al-Fuqaha, A.; Guizani, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Aledhari, M.; Ayyash, M. Internet of Things: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Protocols, and Applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 17, 2347–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, G.; Gungor, V.C. A survey on deployment techniques, localization algorithms, and research challenges for underwater acoustic sensor networks. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2017, 30, e3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashtarian, F.; Sohraby, K.; Varasteh, A. Multihop data gathering in wireless sensor networks with a mobile sink. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2017, 30, e3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Yang, K. Routing Protocols Analysis for Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Control Engineering, Shanghai, China, 24–26 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, E.; Yaqoob, I.; Gani, A.; Imran, M.; Guizani, M. Internet-of-things-based smart environments: State of the art, taxonomy, and open research challenges. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2016, 23, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, A.; De Donato, W.; Persico, V.; Pescapé, A. Integration of Cloud computing and Internet of Things: A survey. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2016, 56 (Suppl. C), 684–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Gupta, P.; Wahab, M.H.A. Smart Collision Avoidance and Hazard Routing Mechanism for Intelligent Transport Network. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rath, M.; Pati, B.; Pattanayak, B.K.; Panigrahi, C.R.; Sarkar, J.L. Load balanced routing scheme for MANETs with power and delay optimisation. Int. J. Commun. Netw. Distrib. Syst. 2017, 19, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzgiene, R.; Narbutaite, L.; Adomkus, T. MANET network in Internet of things system. Ad Hoc Netw. 2017, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, P.; Muhlethaler, P.; Clausen, T.; Laouiti, A.; Qayyum, A.; Viennot, L. Optimized link state routing protocol for ad hoc networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Multi Topic Conference, IEEE INMIC, Lahore, Pakistan, 28–30 December 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, R.C.; Gonzalez-Herrera, I.; Bromberg, Y.D.; Réveillère, L.; Rivière, E. Density and Mobility-Driven Evaluation of Broadcast Algorithms for MANETs. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 37th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Atlanta, GA, USA, 5–8 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, O.; Sekercioglu, Y.A.; Mani, N. A survey of multipoint relay based broadcast schemes in wireless ad hoc networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2006, 8, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakrami, F.; Elkamoun, N.; El Kamili, M. A survey on QoS for OLSR routing protocol in MANETs. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Ubiquitous Networking, Casablanca, Morocco, 8–10 Septmber 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Trakadas, P.; Zahariadis, T. Design Guidelines for Routing Metrics Composition in LLN. Roll Internet Draft, 24 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Souidi, M.; Habbani, A.; Berradi, H.; Essaid, B. Node localization to optimize the MPR selection in smart mobile communication. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Smart Digital Environment, Rabat, Morocco, 21–23 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Souidi, M.; Habbani, A.; Berradi, H.; El Mahdi, F. Geographic forwarding rules to reduce broadcast redundancy in mobile ad hoc wireless networks. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Weng, N.; Vespa, L. Enhancing Sensor Network Data Quality via Collaborated Circuit and Network Operations. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2013, 2, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Zhou, J. An improved hybrid location-based routing protocol for ad hoc networks. In Proceedings of the 2011 7th International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing, Wuhan, China, 23–25 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Totani, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Utsu, K.; Ishii, H. An efficient broadcast-based information transfer method based on location data over MANET. J. Supercomput. 2016, 72, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, K.; Selvakumar, K.; Nithya, T.; Sathyabama, S. Zone based multicast routing protocol for mobile ad-hoc network. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Emerging Trends in VLSI, Embedded System, Nano Electronics and Telecommunication System (ICEVENT), Tiruvannamalai, India, 7–9 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.U.; Tapus, N. CEHR: Core enabled hybrid routing protocol for mobile ad hoc networks. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 10th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), Cluj Napoca, Romania, 4–6 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.H.; Mostafa, S.A.; Budiyono, A.; Mustapha, A.; Gunasekaran, S.S. A Hybrid Algorithm for Improving the Quality of Service in MANET. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2018, 8, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, R.S.; Kumar, N.; Rodrigues, J.J. An efficient energy-aware predictive clustering approach for vehicular ad hoc networks. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2017, 30, e2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Baz, A.; El-Sayed, A. A new algorithm for cluster head selection in LEACH protocol for wireless sensor networks. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2018, 31, e3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majma, M.R.; Foladi, M.D.; Pedram, H.; Almassi, S. Grid based data dissemination protocol for mobile sink in wireless sensor network. In Proceedings of the 2012 2nd International eConference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE), Mashhad, Iran, 18–19 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, C.; Duong, T.Q.; Guizani, M.; Karagiannidis, G.K. A Survey on Mobile Anchor Node Assisted Localization in Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 18, 2220–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallikannu, R.; George, A.; Srivatsa, S. Autonomous localization based energy saving mechanism in indoor MANETs using ACO. J. Discret. Algorithms 2015, 33, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiro Martínez-de Dios, J.; Ollero, A.; Fernández, F.; Regoli, C. On-line RSSI-range model learning for target localization and tracking. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2017, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A.; Viennot, L.; Laouiti, A. Multipoint relaying for flooding broadcast messages in mobile wireless networks. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS, Big Island, HI, USA, 10 January 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kitasuka, T.; Tagashira, S. Finding more efficient multipoint relay set to reduce topology control traffic of OLSR. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 14th International Symposium and Workshops on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM), Madrid, Spain, 4–7 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.; Chen, M.; Deng, J.; Hassan, M.M.; Fortino, G. Enhanced fingerprinting and trajectory prediction for IoT localization in smart buildings. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2016, 13, 1294–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Biswas, G. Networking for IoT and applications using existing communication technology. Egypt. Inform. J. 2018, 19, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Network Simulator NS-3. Available online: https://www.nsnam.org/ (accessed on 29 June 2019).

- Aschenbruck, N.; Ernst, R.; Gerhards-Padilla, E.; Schwamborn, M. BonnMotion: A mobility scenario generation and analysis tool. In Proceedings of the 3rd International ICST Conference on Simulation Tools and Techniques, Malaga, Spain, 15–19 March 2010; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, G.; Fortuna, P.; Ricardo, M. FlowMonitor: A network monitoring framework for the network simulator 3 (NS-3). In Proceedings of the Fourth International ICST Conference on Performance Evaluation Methodologies and Tools, Pisa, Italy, 20–22 October 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).