Abstract

This study examines the impact of gender as a social factor on the lexical variation of the Jordanian currency, dinar, among students at the University of Jordan. Utilizing a mixed-method approach, the study aims to determine whether the role of gender is statistically significant in the choices among different lexical variants of the terms. For quantitative results, the chi-square test of independence, conducted after distributing a questionnaire to 510 participants, revealed that gender significantly influences lexical choices. Furthermore, data obtained from fifty audio-recorded interviews revealed that the majority of participants agreed with the findings from the quantitative analysis. Applying Gender Performativity Theory to analyze these choices socially and the meanings conveyed by their usage reveals that lexical preferences in Jordan are deeply connected with societal expectations regarding gender roles.

1. Introduction

In sociolinguistic studies, the relationship between language and gender has been a major topic, particularly in variationist research (e.g., Al-Wer, 1997; Omari & Jaber, 2019; Zibin & Al-Tkhayneh, 2019). Men and women are integral parts of their culture, where they acquire specific ways of speaking and the gendered connotations tied to different forms of speech, which, in turn, shape their behaviors through these meanings (Cameron, 1998, p. 28). In fact, the practice of gender can differ significantly depending on cultural, geographical, and social contextual factors, influenced by the intersection of various aspects of social identity (Eckert, 1998, p. 66). In Jordanian society, Al-Harahsheh (2014) argued that social expectations shape the way men and women communicate. In the context of language variation, Al-Wer (1997) demonstrated that Jordanian speakers are aware of the gender and identity connotations associated with certain linguistic forms. According to Tannen (1990), these differences in communication patterns are not individual but are deeply rooted in social constructs and power relations. Such differences in language use between men and women can perpetuate traditional gender roles, leading to broader social inequalities.

Research shows that gender plays a significant role in variationist studies because men and women often have different linguistic preferences (Cheshire, 2006; Zibin et al., 2024). While these studies can explore various aspects of language (like phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics) (Al-Tamimi, 2020), much of the research on the Arabic language has been limited to just a few phonological variables (Miller, 2007, p. 2). This study seeks to broaden variationist research in Jordanian Arabic by examining the different lexical terms related to Jordanian currency at the semantic level. We have observed that Jordanian university students use various terms associated with the Jordanian currency dinar, such as lira and nira. Our goal is to show how this lexical variation in word choice is influenced by gender as a social factor.

Investigating the different terms related to the Jordanian currency dinar is vital for understanding the broader sociolinguistic landscape of Jordanian society. These variations can highlight how language reflects and shapes gender identities and social roles. The lexical choices made by Jordanian university students, e.g., lira and nira, provide valuable insights into the impact of gender. By focusing on this specific group, researchers can account for variables such as education and age, allowing them to isolate gender as a crucial element in language variation. The findings from such studies go beyond just linguistic interest; they illustrate how language can reinforce social norms and power dynamics, potentially uncovering ways to tackle gender-based inequalities. This emphasis on lexical variation contributes to the growing body of research in Arabic, which acknowledges the significance of lexical differences alongside traditional studies focused on phonology. While works by Azaz and Alfaifi (2022) and Almujaiwel (2020) have investigated different aspects of lexical variation in regional Arabic, this study deepens our understanding of language use by looking at how lexical choices related to the Jordanian currency are shaped by cultural and social factors (see Altakhaineh et al., 2024b).

Selecting university students in Jordan as the focus group controls for the influence of educational levels as a social factor while emphasizing the impact of gender on lexical variation. This selection allows for a more precise examination of gender differences, minimizing potential confounding effects of varying educational backgrounds. Furthermore, controlling for educational level as a social factor ensures that all participants belong to similar educational settings, thereby addressing the age factor by including individuals within the same age group. University students represent a younger demographic; hence, this sample was chosen due to the dynamics of this educational level, where young speakers often lead language variation by pushing boundaries and adopting emerging trends in linguistics (Al-Klabani, 2024, p. 45). The members of the focus group of university students in this study provide valuable insights into language variation by engaging with new linguistic norms and serving as trendsetters in language use.

This study seeks to explore the lexical choices of Jordanian university students and how these choices are influenced by gender. The central research questions are as follows:

- Is there a significant gender-based variation in the use of different lexical choices of the word dinar among Jordanian university students?

- What social meanings are conveyed by these lexical choices?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Language, Identity, and Lexical Variation

2.1.1. Linguistic Choices as a Gender Marker

The connection between language and gender is deep and flexible, shaped by our social interactions (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 2003, p. 34). As a result, the way individuals choose to speak plays a substantial role in how they present themselves as men and women in different situations (p. 42). Research shows that there are clear differences in how genders use language, particularly in areas like pronunciation, word choice, and grammar (Piersoul & Van de Velde, 2023). These differences not only show up in the data but also have social meanings (Pennebaker et al., 2003). For example, women often use verbal fillers, hedges, politeness markers, and qualifiers, which reflect a conversational style that is less assertive and more thoughtful (Lakoff, 1973). On the other hand, men’s speech is usually more direct and assertive, often including commands and interruptions that mirror traditional gender roles and power structures (Tannen, 1990). Therefore, exploring how language varies by gender is crucial for understanding gender dynamics and stereotypes in communication (Lakoff, 1973). These differences can be seen at various levels of language, including sound, vocabulary, and morphosyntax (Coates, 1998).

2.1.2. Labovian Approach and Gendered Lexical Variation

Language variation is essential for understanding how different linguistic structures correspond with practical usage in daily life (Holmes, 2006). As Labov (1972, p. 271) posits, language variation can be defined as “two or more ways of saying the same thing”, and can manifest in variations of sounds, words, sentences, and meanings (Al-Klabani, 2024, p. 3). While previous research has predominantly concentrated on phonological variation (see Al-Shawashreh, 2016), the influence of sociolinguistic factors on lexical variation remains under-explored (Altakhaineh et al., 2024b). Tannen (2007) notes that lexical variation encompasses differences in word usage and vocabulary choices shaped by an individual’s gender, reflecting societal norms and expectations regarding gender roles and identities. Consequently, the influence of gender on lexical variation is apparent and is molded by social, cultural, and contextual factors (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 1992).

Labov (1990, 2001) explores the idea of the “Gender Paradox” in sociolinguistic research within Western communities. He points out that women’s use of language can be either traditional or cutting-edge, depending on the situation. He also notes that men often use nonstandard language more frequently in stable settings than women do, who are usually seen as trendsetters in language evolution. This means that women tend to stick to well-defined language rules more than men, although they are less likely to follow these rules when they are not clearly laid out (Labov, 1990, 2001). In simpler terms, women are more inclined to use language that is viewed as prestigious rather than that which carries a stigma (see Labov, 2001). Interestingly, men usually have a more intricate way of speaking, although they lack in lexical diversity (see Piersoul & Van de Velde, 2023). Nevertheless, the gap in language use between genders has been narrowing (Piersoul & Van de Velde, 2023).

2.2. An Overview of Gender and Language Variation in the Jordanian Context

Sociolinguists have adopted an approach to examining various aspects of language variation (e.g., age, gender, region) that “have proved useful to variationists in revealing remarkably consistent sociolinguistic patterns” (L. Milroy & Gordon, 2003, p. 116). A substantial and growing body of literature on Arab communities and Jordanian society argues that gender plays a critical role in language variation (e.g., Al-Wer, 1997; Al-Ali & Arafa, 2010; Omari & Van Herk, 2016). For instance, Al-Ali and Arafa (2010) demonstrated that women and men do not choose linguistic variants arbitrarily; rather, their choices are influenced by gender motivations and social expectations. Consequently, one possible explanation for the variation in female speech patterns is their alignment with prestigious norms (Al-Ali & Arafa, 2010). In a similar vein, Zibin et al. (2024) argued that pronunciation and writing styles may indirectly signify gender identity within communities of practice (e.g., social media), based on the principles of indexicality. Furthermore, Al-Wer (1997) posited that Jordanian speakers are aware of the associations between certain linguistic forms and gender and identity connotations. Therefore, while prior literature in the Jordanian context emphasizes the crucial role of gender in sociolinguistic studies, the current study specifically focuses on analyzing gender as a social factor in language variation, particularly within the domain of lexical variation, which has not been sufficiently explored in previous research.

2.3. Gender Performativity Theory: Theoretical Framework

Instead of understanding gender as an inherent characteristic, it should be viewed as an ongoing performance conveyed through repeated actions, thereby emphasizing the concept of “doing gender” (Salih, 2002). According to Butler (1990, p. 33), gender is constructed through the repeated performance of bodily acts, which, over time and within a rigid regulatory context, create the perception of a natural and substantial source of being. Consequently, within the traditional framework of metaphysics of substance, gender is performative, meaning that the formation of identity is intended to signify (Butler, 1990). Similarly, MacKinnon (1993, p. 18) posited that performativity is not merely a formal characteristic of language but also a practice deeply rooted in social, cultural, and bodily dimensions. Therefore, cultural and social contexts play a crucial role in shaping gender, as individuals’ performances can vary based on the societal norms and expectations they encounter (Butler, 1990, p. 136). While gender performativity suggests that identity is a product of our actions, it implies that these actions are influenced by specific semiotic choices (e.g., meaning-making) within given constraints (see Milani, 2019). This theory proposed by Butler (1990) can be applied to understand the repeated actions and behaviors that conform to social norms and expectations in shaping gender identity within a society, such as Jordan. According to Al-Sallal and Ahmed (2020), Jordanian cultural norms influence gender-specific speech behaviors, with men often employing a more formal and authoritative tone. In contrast, Jordanian women are typically expected to utilize more polite and less confrontational language, aligning with broader cultural expectations of femininity (Abu-Lughod, 1999). This study aims to explore the social meanings conveyed by the gendered lexical variation of the Jordanian currency dinar among Jordanian university students.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

The current study employed a sample of 600 participants, divided into two groups: (1) 550 participants who completed a questionnaire, and (2) a second group comprising 50 participants who were interviewed for data triangulation. The second group of participants was selected conveniently, as explained in Section 3.2. All participants were within the age range of 20–24 years, and they were all pursuing bachelor’s degrees. They were selected from various faculties at the University of Jordan (e.g., Law, Medicine, Foreign Languages, Arts, and Business). The University of Jordan was chosen for this study due to its status as one of the largest universities located in Amman, the capital of Jordan. It attracts a diverse student population from various regions and social classes, making it a central hub for higher education in the country.

To ensure that the sample met the study’s criteria, participants were screened to exclude those who did not reside in Jordan, thereby maintaining focus on Jordanian students and ensuring the validity and reliability of the study’s findings. Following this screening process, out of the 550 participants sampled originally for the first group, a total of 510 responses were collected after excluding 40 responses that did not meet the specified criteria. The sample was balanced between male and female respondents to ensure gender representation in the first group (255 men and 255 women). The second group of 50 participants was stratified into two balanced samples (25 men and 25 women) who were interviewed for data triangulation.

To achieve validity and credibility, research triangulation was utilized to gain a comprehensive understanding of the research topic and deeper insights into the results (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Triangulation facilitates the integration and cross-verification of data from multiple perspectives to mitigate biases and errors (Altakhaineh et al., 2024a). Furthermore, ethical considerations were upheld throughout the data collection process, ensuring confidentiality and obtaining informed consent from all participants. Consent forms were gathered prior to data collection for both groups, and participants were informed of the general purpose of this study. Participation was voluntary, with participants aware that they could withdraw at any time without any consequences, and that their data would be anonymized and securely stored.

3.2. Data Collection

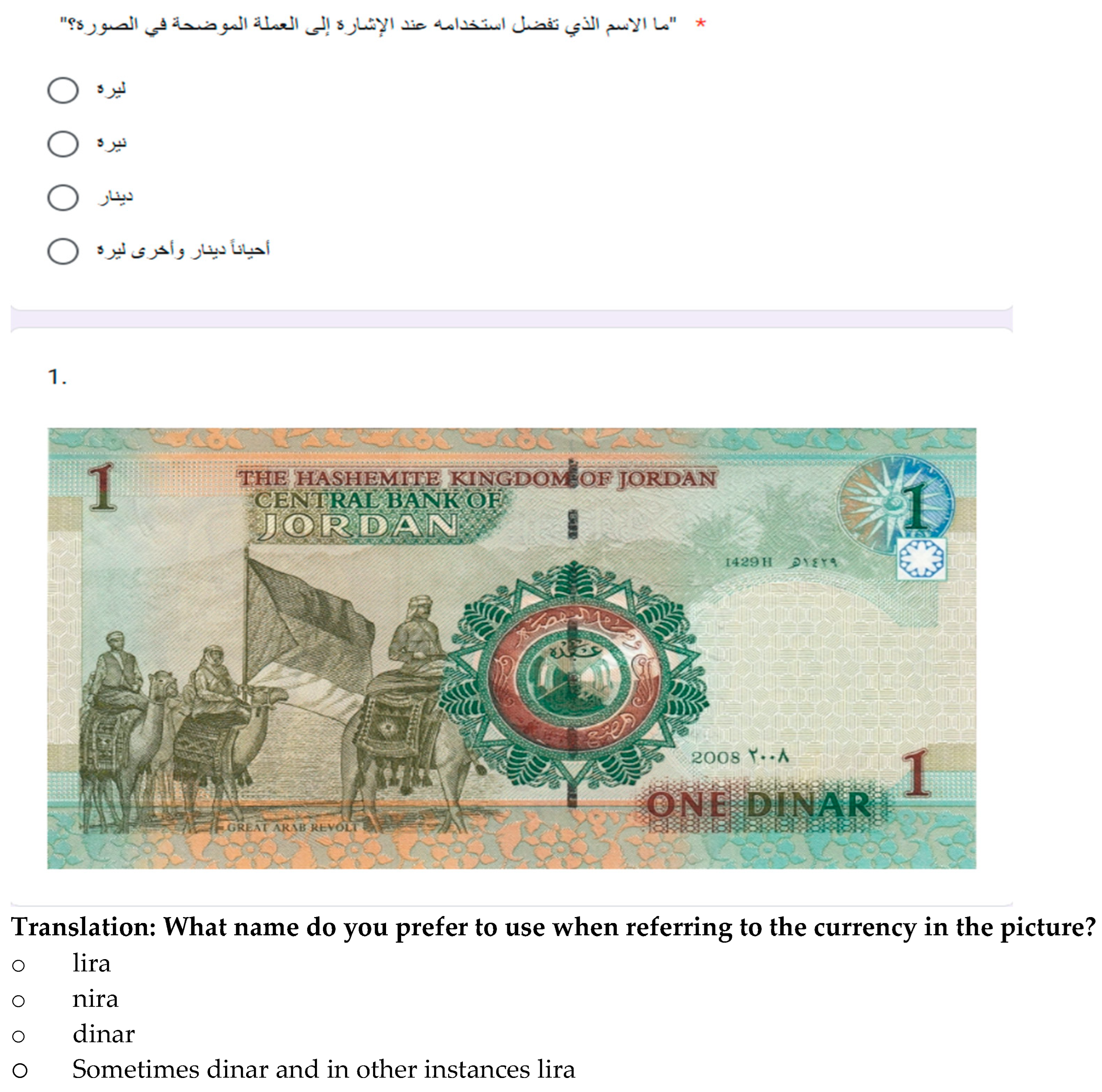

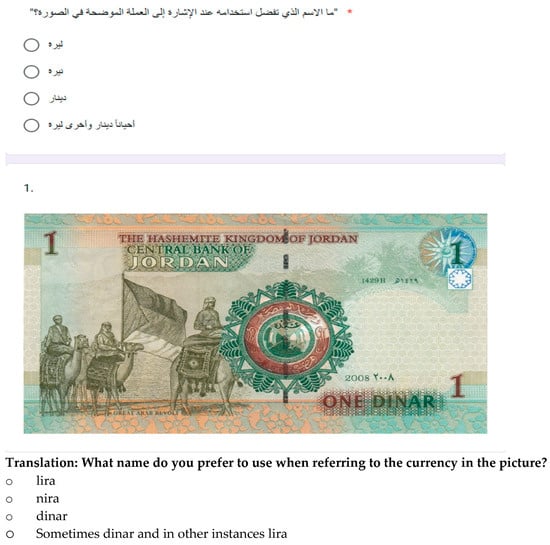

The methodological approach adopted in this study is a mixed methodology, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative techniques to assess the role of gender in the lexical variation of currency terms—specifically dinar, lira, and nira—among Jordanian university students. It should be noted that each variant can be pluralized to indicate an increase in number, so one can say, e.g., ʔarbaʕ dana:ni:r “four dinars”, xams li:ra:t “five dinars (li:ra:t)”, sabʕ ni:ra:t “seven dinars (ni:ra:t)”. To collect quantitative data and analyze the impact of gender on the lexical variation of Jordanian currency terms among university students, a colored image of a banknote dinar was presented to the participants as a part of the questionnaire, and the participants were asked to choose the term they use to describe the image in their own words (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A screenshot of a part of the questionnaire used in this study.

The responses were subsequently placed into an Excel file, which displayed the distribution of the collected data. All tokens were then coded in the Excel file according to gender distribution for various variants of the Jordanian currency dinar.

To complement the quantitative data obtained from the questionnaire, a qualitative data elicitation tool was employed through audio-recorded interviews conducted at the University of Jordan. One of the authors collected data from participants, who were sampled conveniently (see Section 3.1). Participants were asked for their opinions on the findings. Each interview lasted approximately 15 minutes and was tape-recorded with the participants’ consent. This method was utilized to gather diverse insights into participants’ perspectives, allowing for multiple interpretations and contextual data (Rubin & Rubin, 2011; Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Below are some of the questions used in the interviews:

- Do you believe that social expectations influence the choices of different forms of the Jordanian currency dinar among male and female students at Jordanian universities? If so, how?

- Based on the study’s results, do you think that there are differences in the forms related to the Jordanian currency dinar as used by male and female students at universities in Jordan? Why or why not?

- Why do female students at universities tend to use the term dinar more frequently than other forms of the Jordanian currency compared to male students in Jordan?

- If one uses the variant lira or nira over dinar, what reasons could have driven such a choice?

3.3. Data Analysis

A chi-square test of independence was employed in the current study to examine the relationship between gender as a social factor and the choice of various variants of the Jordanian currency term dinar among Jordanian university students. This non-parametric statistic, in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics V. 30), is effective for comparing differences between groups when the dependent variables are at the nominal level (McHugh, 2013). A key strength of the chi-square test lies in its robustness, as it does not require the data to conform to a specific distribution or the assumption of equal variance (McHugh, 2013).

The interview responses were analyzed using thematic analysis, a qualitative research method that helps researchers identify and interpret patterns or themes in the data (Braun et al., 2019). After the data were collected, the recordings were transcribed word for word, and the authors reviewed the transcripts several times to become familiar with the material. Following this, initial codes were created based on recurring ideas and concepts found in the responses. These codes were then grouped into broader themes that highlighted important insights related to social expectations, gender differences, and language use regarding the Jordanian currency. To ensure the reliability and validity of the analysis, inter-rater reliability was established using Cohen’s Kappa (Braun et al., 2019). This involved multiple researchers independently coding a subset of the data, and then comparing their coding to check for agreement. Any discrepancies were discussed until everyone reached a consensus.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

To assess whether there are statistically significant differences (α < 0.05) concerning the relationship between gender as a social factor and the selection of various lexical variants of the Jordanian currency dinar among Jordanian university students, a chi-square test of independence was conducted. The results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The results for variants according to the gender variable.

The results presented in Table 1 indicate a statistically significant relationship between the two variables, with X2 = 57.823 and p = 0.001. Both male and female participants demonstrated a preference for the variant dinar; however, notable differences were observed in the usage percentages: 79.6% of females utilized this variant, in contrast to 47.4% of males. Regarding the variant lira, 35.6% of males preferred it, while only 16.1% of female participants did. Lastly, the variant nira was used by 16.9% of male participants, compared to 4.3% of female participants. It is notable that both genders use all the variants, but they do so at different rates. This pattern suggests that Jordanian society may be shaped more by gender-preferential language use rather than a strictly gender-exclusive language system. According to Holmes (2013), this preference shows that language mirrors social identity and cultural norms instead of rigid boundaries. The differing usage rates of dinar, lira, and nira between the two genders highlight how linguistic choices are influenced by societal expectations regarding gender roles. While both genders use the same lexical variants, the differences in frequency reveal the complex relationship between gender and language in Jordan, where certain terms may have different meanings or implications based on the speaker’s gender.

4.2. Qualitative Results

To gain deeper insight into the responses obtained from the questionnaire, audio-recorded interviews were conducted with 50 participants at the University of Jordan. These interviews revealed that 46 out of the 50 participants concurred with the findings of the current study and provided comprehensive explanations for each question. Generally, the interviewees indicated that gender plays a significant role in their speech community. For instance, in response to the first question in the interview, one participant stated the following (translated into English):

Yes, it is a cultural thing and the societal expectations in our country affects how we express ourselves. For example, if a guy uses a word that is considered ‘girly’, his friends might make fun of him. However, girls might use certain words to sound more ‘girly’ around other girls, even if they do not usually use them due to our social expectations.(male interviewee)

However, another interviewee stated the following (translated into English):

In my opinion, the differences in word choices are more about personality. For example, I do not feel that social expectations change the way I speak. I use the same words that reflect my personality. I use dinar because this is how I speak.(female interviewee)

In addition, to obtain detailed insights into the differing opinions regarding notable distinctions in terms related to the Jordanian currency, dinar, between male and female students at universities in Jordan, one interviewee made the following remark (translated into English):

Yes, there are differences between males and females in the usage of these variants. Males often tend to use slang terms like nira more casually, while girls might stick to the formal term dinar. I think girls might use softer or more polite terms, but males tend to use humorous slang.(female interviewee)

On the other hand, another interviewee argued the following (translated into English):

Using these variants among university students in Jordan is popular in our youth culture. Yes, there are some differences between them. For example, I would expect a male to say nira more than females.(Male interviewee)

Another one commented the following (translated into English):

I disagree, I have seen girls who use slang terms such as lira, in some contexts, so it is really about the people you are talking to.(male interviewee)

For the third question about the tendency of females to use the variant dinar more than other variants of the Jordanian currency compared to male students in Jordan, one interviewee pointed out the following (translated into English):

I think girls are more influenced by how they are perceived when they talk, so they might avoid slang and prefer dinar more than other variants to come off as more polished or refined by using the formal variant.(female interviewee)

However, another interviewee argued the following (translated into English):

Both male and female switch between these variants depending on who they are with and what they are talking about although females are more careful about what they say and in front of whom.(Male interviewee)

The interviews provide a glimpse into how gender shapes the way young participants in Jordan talk about their currency, particularly the dinar. This highlights the idea of gender performativity, which suggests that gender is not something we are born with, but rather a set of behaviors and expressions that society constructs and reinforces through language and communication.

The interviews demonstrate clear differences in the word choices of male and female participants. Male students often use informal slang terms like nira, which helps them assert their masculine identity and bond with peers. In contrast, female students tend to use the more formal term dinar, reflecting a deliberate choice to present a feminine identity that aligns with societal expectations of decorum and sophistication.

Participants recognized that societal norms greatly influence their language. For instance, one male interviewee shared that he faced teasing for using “girly” words, illustrating the cultural pressures surrounding masculinity and the constraints on acceptable expression. On the other hand, a female participant explained that her preference for dinar over slang is a strategic choice to project a polished image, showcasing the performative aspects of femininity and the societal pressures to meet standards of propriety.

The interviews also shed light on how context affects language choices. One male interviewee mentioned that he tends to use slang casually with friends but switches to formal language when around women or family. This adaptability shows an awareness of social dynamics and indicates that gender performance can change depending on the audience (see Zibin et al., 2024).

Responses further highlighted that language is a key reflection of identity and power dynamics. One female interviewee noted that using dinar can help girls appear more refined, suggesting a desire to assert authority and navigate the complexities of social status within their community. This shows that language choices go beyond mere communication and are essential to the ongoing performance of gender identity.

Interestingly, participants pointed out generational differences in language use, with younger individuals more likely to adopt slang, reflecting shifting cultural norms. The fact that younger participants use dinar to convey sophistication suggests an understanding that language can signal cultural identity and status, adding depth to the performance of gender in conversation.

In general, the qualitative data reveal a complex relationship between gender and language use in discussions about the Jordanian currency. It is clear that the participants’ language choices are influenced by societal expectations, contextual factors, and their own identity negotiations. The findings highlight the significant role of gender in language, illustrating how it serves as a powerful tool for expressing identity, authority, and belonging within their community, effectively performing the gender roles that society prescribes.

5. Discussion

To contextualize the findings within the research areas discussed in the literature review, this section aims to address the research questions by exploring the implications of the current results. The quantitative and qualitative analysis of the lexical variation among Jordanian university students based on gender reveals several noteworthy outcomes.

Concerning the first research question regarding the role of gender-based variation in the use of different lexical choices related to the Jordanian currency dinar among university students, the chi-square test indicates that gender is a significant factor in the lexical variation observed. The results demonstrate that both male and female students prefer the variant dinar over other variants; however, a significantly higher percentage of females (79.6%) prefer to use dinar compared to males (47.4%). The variant lira is predominantly utilized by males, with a usage rate of 35.6%, while only 16.1% of females employ it. These findings align with previous studies indicating that gender is a crucial factor in variationist studies (e.g., Al-Wer, 1997; Al-Ali & Arafa, 2010), which have suggested that females tend to prefer prestigious linguistic variants more than males. In the present study, the findings indicate that the variant dinar, which is regarded as the formal variant among the various forms of the Jordanian currency, is used more frequently by female students than by male students. This preference suggests that female students are typically more attuned to the norms of linguistic behavior and the standard variants associated with prestige. This analysis is in line with previous research on how gender influences language use (e.g., J. Milroy et al., 1994). It suggests that women typically prefer language features that reflect broader societal norms and prestige. On the other hand, men are often linked to more localized speech patterns, which can include nonstandard forms. This observation is consistent with Labov’s (1990) findings, which showed that men are more likely than women to use nonstandard variants in stable language situations. So, while women might lean toward language that is more socially accepted, men tend to embrace informal, localized speech as part of their identity.

Moreover, these results affirm that the choices of linguistic variants by females and males are not arbitrary; rather, they are influenced by gender-specific motivations and social expectations (see Al-Ali & Arafa, 2010). Regarding the second research question concerning the social meaning conveyed by the usage of different variants of the Jordanian currency dinar among university students, several theoretical perspectives and research findings can clarify that these variants in lexical choice are not merely functional elements; they also reflect social meanings within society. Through the lens of Gender Performativity Theory, as proposed by Butler (1990), gender is influenced by cultural and social contexts, and the performance of gender can vary according to societal expectations and norms. In Jordan, the speech behavior of males and females is shaped by cultural expectations (Al-Sallal & Ahmed, 2020). Women generally utilize more prestigious language forms than men, adhering to overt, standard norms; conversely, men tend to employ covert, vernacular language (Malkawi, 2011). The findings from the current study reveal a significant divergence in the lexical choices of the Jordanian currency dinar among male and female students at Jordanian universities. Women’s reliance on more standard terms, such as dinar, can be seen as an effort to gain prestige in society, while men often adopt more informal terms like lira and nira as markers of masculinity. These results align with societal expectations regarding gender performativity in Jordan and suggest that the variation in lexical choices between Jordanian males and females reflects and responds to these norms.

Building on Gender Performativity Theory (Butler, 1990), this study reveals that gender is not only reflected but actively constructed through language in Jordanian society. The preference among female students for more prestigious, standard terms like dinar can be viewed as a strategic performance of femininity that aligns with societal norms that associate women with formality and correctness. This linguistic choice may help them negotiate social capital in line with cultural expectations of female propriety and respectability. Conversely, male students’ use of less formal terms such as lira and nira can be interpreted as performative acts embodying traditional masculine identities, often characterized by a rejection of overt prestige in favor of local solidarity. Through these linguistic performances, students express their individual identities while simultaneously reinforcing societal gender norms. This finding highlights the connection between language, identity, and societal power structures, which shows how everyday linguistic choices contribute to the ongoing construction of gender identity in Jordanian culture.

In sum, the analysis highlights several important themes about how gender impacts language use among young participants in Jordan, viewed through the concept of Gender Performativity:

- Gendered Language Choices: Male students often use informal slang terms like nira, which reflects their masculine identity and helps them bond socially. In contrast, female students tend to use the more formal term dinar, making a strategic choice that aligns with societal expectations of femininity.

- Societal Norms and Identity: The way participants use language is influenced by societal norms. Male respondents feel pressured to stick to traditional masculine speech, avoiding terms that might be seen as “girly”. Female students use dinar intentionally to maintain a polished image, indicating that their language choices are performative acts designed to navigate societal pressures.

- Contextual Influences: The interviews show that context plays a significant role in language use. Male participants adjust their language depending on their social environment, opting for more casual slang with friends and switching to formal language when speaking to women or family, demonstrating their awareness of how different situations affect their gender expression.

- Power Dynamics and Authority: Language reflects identity and power dynamics, with female students noting that using dinar can convey refinement and authority. This suggests that women may employ specific linguistic strategies to assert their status in social settings.

- Generational Variations: Some participants point out that younger individuals are more likely to embrace slang, indicating changing cultural attitudes toward gender and language. The younger generation’s use of dinar to express sophistication shows a complex relationship between language, cultural identity, and shifting gender roles.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that gender is an important factor in the lexical variation of the Jordanian currency dinar among university students. Utilizing a mixed-method approach, the findings provide an illustration of how lexical choices are influenced by gendered expectations in Jordan. Chi-square results indicate that gender is statistically significant, revealing that the lexical choices associated with the Jordanian currency dinar can be gendered. In this study, while both males and females preferred the variant dinar, there were notable differences in their usage rates: females favored dinar at a rate of 79.6%, compared to males at 47.4%. The variant lira was more commonly used by males, with a usage rate of 35.6%, while only 16.1% of females employed this variant. To triangulate the results, the qualitative approach confirmed that most participants agreed with the quantitative findings, thereby enhancing the study’s validity and credibility. Furthermore, this study explored the societal meanings conveyed by this lexical variation in Jordan through the lens of Gender Performativity Theory. The results indicate that this variation aligns with prevailing social norms and expectations in Jordan. Overall, these findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the relationship between language and gender in Jordan and highlight the role of linguistic variation as a medium through which gender roles are constructed.

This study goes beyond just sociolinguistics; it highlights the wider dynamics of gender in Jordanian society. The clear differences in word choices show that language is not just a way to communicate; it also reflects cultural values and power dynamics. These findings can guide future research by highlighting the importance of digging deeper into how language practices might reinforce or challenge existing gender norms. Additionally, understanding these dynamics can help us recognize how language shapes societal expectations and identity, sparking important conversations about empowerment in Jordan. Future research could build on these insights by looking at how language preferences change across different social contexts and generations, enriching the conversation about gender and language both locally and globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.M.A., N.J.A. and A.Z.; methodology, A.R.M.A.; software, A.R.M.A.; validation, A.R.M.A., N.J.A. and A.Z.; formal analysis, A.R.M.A., N.J.A. and A.Z.; investigation, A.R.M.A.; resources, A.R.M.A. and A.Z.; data curation, A.R.M.A. and N.J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.M.A., N.J.A. and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.R.M.A., N.J.A. and A.Z.; supervision, A.R.M.A. and A.Z.; project administration, A.R.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research and Ethical Committee of The School of Foreign Languages at The University of Jordan (1/12/8/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abu-Lughod, L. (1999). Veiled sentiments: Honor and poetry in a Bedouin society. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ali, M. N., & Arafa, H. I. M. (2010). An experimental sociolinguistic study of language variation in Jordanian Arabic. The Buckingham Journal of Language and Linguistics, 3, 220–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harahsheh, A. (2014). Language and gender differences in Jordanian Spoken Arabic: A sociolinguistics perspective. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4(5), 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Klabani, F. (2024). Social variation of English tautological compounds in Ammani Arabic [Master’s thesis, The University of Jordan]. [Google Scholar]

- Almujaiwel, S. (2020). An overview of the lexical variation between Arabic Lexicons and Natural Arabic Language. International Journal of Arabic Linguistics, 6(1–2), 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sallal, R., & Ahmed, M. (2020). Gender differences in using apology strategies in Jordanian spoken Arabic. International Journal of English Linguistics, 10(6), 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shawashreh, E. (2016). Aspects of grammatical variation in Jordanian Arabic [Doctoral dissertation, Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa]. [Google Scholar]

- Altakhaineh, A. R. M., Zibin, A., & Al-Kalbani, F. (2024a). An analysis of Arabic tautology in English compounds used in customer-service settings in Jordan: A pragmatic perspective. Journal of Pragmatics, 220, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altakhaineh, A. R. M., Zibin, A., & Khalifah, L. (2024b). A horn of pepper or a head of onion: An analysis of semantic variation of classifiers in Jordanian Spoken Arabic from a cognitive sociolinguistic approach. Languages, 9, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi, Y. A. (2020). /dʕ/-variation in Saudi newscasting and phonological theory. International Journal of English Linguistics, 10(4), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-Wer, E. (1997). Arabic between reality and ideology. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaz, M., & Alfaifi, E. (2022). Lexical variation in regional modern standard Arabic. Language Matters, 53(1), 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis 48. In V. Braun, V. Clarke, N. Hayfield, G. Terry, & P. Liamputtong (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and subversion of identity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, D. (1998). Performing gender identity: Young men’s talk and the construction of heterosexual masculinity. In J. Coates (Ed.), Language and gender: A reader (pp. 270–284). Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, J. (2006). Sex and gender in variationist research. In J. K. Chambers, P. Trudgill, & N. Schilling-Estes (Eds.), The handbook of language variation and change (pp. 423–443). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J. (1998). Language and gender: A reader. Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, P. (1998). Gender and sociolinguistic variation. In J. Coates (Ed.), Language and gender: A reader (pp. 64–76). Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (1992). Think practically and look locally: Language and gender as community-based practice. Annual Review of Anthropology, 21, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2003). Language and gender. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J. (2006). Workplace narratives, professional identity and relational practice. Discourse and Identity, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. (2013). An introduction to sociolinguistics. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W. (1990). The intersection of sex and social class in the course of linguistic change. Language Variation and Change, 2(2), 205–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (2001). Principles of linguistic change: Social factors. Blackwell Publishers. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781444327496 (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Lakoff, R. (1973). Language and woman’s place. Language in Society, 2(1), 45–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, C. (1993). Only words. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malkawi, A. H. (2011). Males’ and females’ language in Jordanian society. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2(2), 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M. L. (2013). The Chi-square test of independence (pp. 143–149). Biochemia Medica. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, T. M. (2019). Queer performativity. In The Oxford handbook of language and sexuality. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C. (2007). Arabic urban vernaculars: Development and change. In C. Miller, E. AlWer, D. Caubet, & J. Watson (Eds.), Arabic in the city: Issues in dialect contact and language variation (pp. 1–32). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Milroy, J., Milroy, L., Hartley, S., & Walshaw, D. (1994). Glottal stops and Tyneside glottalization: Competing patterns of variation and change in British English. Language Variation and Change, 6, 327–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy, L., & Gordon, M. (Eds.). (2003). Sociolinguistics. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, O., & Jaber, A. (2019). Variation in the acoustic correlates of emphasis in Jordanian Arabic: Gender and social class. Folia Linguistica, 53(1), 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, O., & Van Herk, G. (2016). A sociophonetic study of interdental variation in spoken Jordanian Arabic. Jordan Journal of Modern Languages and Literature, 8(2), 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J., Mehl, M. R., & Niederhoffer, K. (2003). Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piersoul, J., & Van de Velde, F. (2023). Men use more complex language than women, but the difference has decreased over time: A study on 120 years of written Dutch. Linguistics, 61(3), 725–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. (2011). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Salih, S. (2002). Judith butler. Routlage. [Google Scholar]

- Tannen, D. (1990). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. Available online: http://www.frankjones.org/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderfiles/tannen.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Tannen, D. (2007). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/You-Just-Dont-Understand-Conversation/dp/0060959622 (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Zibin, A., & Al-Tkhayneh, K. M. (2019). A sociolinguistic analysis of the use of English loanwords inflected with Arabic morphemes as slang in Amman, Jordan. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2019(260), 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibin, A., Daoud, S., & Mitib Altakhaineh, A. R. (2024). Indexical meanings of the realization of/sˤ/ص as [s] س in spoken and written Jordanian Arabic: A language change in progress? Folia Linguistica, 58(2), 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).