Abstract

This paper is concerned with the question of what adverbs in English are as a category. It argues that English adverbs are not positional variants of a single category together with adjectives but also do not constitute a separate lexical category on their own, as is commonly assumed. Instead, this paper advocates the position that adverbs can and should be assimilated with PPs and offers a comprehensive presentation of this view. In particular, it provides evidence that the morpheme -ly is not a suffix but a nominal root, which forms the basis of the analysis of adverbs as PPs. Furthermore, it shows that the PP analysis of adverbs is able to account for a variety of facts, including those that have been previously used as arguments for alternative analyses. Finally, this paper demonstrates that the PP analysis allows for a straightforward compositional semantics, using manner and degree adverbs as case studies, and provides an outlook into the cross-linguistic situation in the domain of adverbs from the perspective of their morphological structure.

1. Introduction: Adverbs in the System of Categories

The categorial status of deadjectival adverbs in English remains largely an open issue, as there is no consensus in the literature as to whether they should constitute a separate lexical category. On the one hand, it appears to be quite standard to assume that the adverbial marker -ly is a category-changing derivational suffix which makes adverbs out of adjectives, i.e., that adverbs do form a separate lexical category distinct from that of adjectives (cf. Payne et al., 2010; Zwicky, 1995). On the other hand, adverbs have never really fit into the system of categories of English, as can be seen particularly well in Chomsky’s (1981) analysis of categories. Chomsky (1981) proposes to represent English lexical categories in terms of the combinations of the [±N] and [±V] features, which allows to refer to natural classes among them (e.g., the [−N] elements are Case-assigners). Crucially, the resulting four-way distinction, presented in the table below, lacks adverbs.

| (1) | [+V] | [−V] | |

| [+N] | A | N | |

| [−N] | V | P |

This has to do with the fact that English adverbs can potentially be assimilated with another category. On the one hand, it can be assumed that adjectives and adverbs are syntactically conditioned variants of a single major category, i.e., that the adverbial marker -ly is an inflectional suffix (cf. Bowers, 1975; Bybee, 1985; Sugioka & Lehr, 1983). This view is supported by the following considerations: the predominant majority of adverbs are formed from adjectives (the remaining not numerous non-deadjectival adverbs can be reanalyzed as belonging to other categories, e.g., degree adverbs like very can be treated as Deg heads), share with adjectives a significant number of properties, and appear to be in a systematic complementary distribution with adjectives. On the other hand, however, adverbs can also be assimilated with PPs (cf. Alexeyenko, 2015; Baker, 2003; Emonds, 1976, 1985), whose syntactic distribution is well known to be near-identical with theirs. This view relies on an analysis according to which the adverbial marker -ly is a nominal root and the base adjective of the adverb is its attributive modifier, both of them being contained inside the structure of a null-headed PP. It is this view that the present paper advocates.

The structure of this paper is as follows. First, Section 2 will present evidence for the PP analysis of English adverbs: it will introduce facts that follow straightforwardly on this analysis but are difficult to explain on existing alternative approaches. After that, Section 3 will show that the PP analysis is also able to account for the facts that have been used as arguments for the alternative approaches (thus also indirectly presenting them), but will also discuss several issues that are potentially problematic for it. In Section 4, it will be shown that the PP analysis also allows for a straightforward compositional semantics of adverbs, using manner and degree adverbs for illustration. Subsequently, Section 5 will provide a brief cross-linguistic outlook into the domain of adverbs in order to gain a somewhat broader perspective in this respect. Finally, Section 6 will conclude.

2. The PP Analysis of Adverbs

The basis of the approach to English adverbs as PPs is formed by the analysis of the adverbial marker -ly in terms of a nominal root rather than a suffix (the term ‘root’ is used pre-theoretically in this paper to refer to non-affixal bound morphemes). The motivation for this analysis will be presented in Section 2.1, which will discuss a number of facts that are difficult to explain under suffixal analyses of -ly but follow straightforwardly if it is analyzed as a nominal root. Based on these facts, Section 2.2 will argue that adverbs are null-headed PPs morphologically fused into single word units whose structure contains the dummy nominal element -ly and the base adjective as its attributive modifier. In Section 2.3, this analysis will then be compared to several alternative possibilities which differ from it in terms of implementation while still belonging to the same overarching PP approach to adverbs.

2.1. Morpheme -ly as a Nominal Root

It is not a well-known fact that, diachronically, the English adverbial marker -ly is of a nominal origin, deriving from the Proto-Germanic noun *lîkom ‘appearance, form, body’.1 Clearly, this fact in itself does not necessarily imply that -ly is also a nominal element synchronically. However, there is evidence that it continues to display nominal behavior in English, while the base adjectives of -ly adverbs continue to display the behavior of attributive modifiers. The strongest piece of evidence for that comes from an argument from the complement-taking capacity of adverbs and adjectives, which has been first advanced in Baker (2003) and later further developed in Alexeyenko (2015). This argument will be presented in Section 2.1.1 below. Subsequently, Section 2.1.2 will discuss a further argument for the view that the morpheme -ly is a root rather than a suffix, which has been proposed in Alexeyenko (2015) and comes from deletion under coordination.

2.1.1. Complement Taking

The starting point of this argument is the observation by Jackendoff (1977, p. 25) that -ly adverbs cannot subcategorize for prepositional, sentential, or infinitival complements, unlike the adjectives they are formed from. Jackendoff provides the following examples to illustrate this claim:2

| (2) | a. | Tired (of the noise), John left the room. |

| b. | Tiredly (*of the noise), John left the room. |

| (3) | a. | Fearful (of a revolt), the king ordered a purge. |

| b. | Fearfully (*of a revolt), the king ordered a purge. |

| (4) | a. | The manner in which John grimaced was expressive (of his needs). |

| b. | John grimaced expressively (*of his needs). |

| (5) | a. | Happy , John waved goodbye. |

| b. | Happily , John waved goodbye. |

| (6) | a. | Eager (), John chewed his nails. |

| b. | Eagerly (), John chewed his nails. |

Jackendoff took these data to be a manifestation of a major syntactic difference between adjectives and adverbs and used them as an argument against the analysis of adverbs as being transformationally derived from adjectives (Jackendoff, 1977, § 2.3). In fact, however, adverbs differ only from predicative adjectives in not being able to take complements, rather than from adjectives in general, and this is what the data in (2)–(6) really show. By contrast, (pre-nominal) attributive adjectives also cannot take complements, patterning with adverbs in this respect. More specifically, pre-nominal adjectives cannot take complements either immediately to their right, being subject to the so-called Head-Final Filter (Alexeyenko & Zeijlstra, 2021; Escribano, 2004; Sheehan, 2017; Williams, 1982), or extraposed across the noun, which would give rise to discontinuous APs (Abney, 1987; Escribano, 2005; Maezawa, 2008).

It is with respect to this latter fact that Baker (2003, pp. 234–235) argues that it speaks in favor of the nominal analysis of -ly. In particular, if the base adjectives of -ly adverbs are attributive modifiers of the nominal morpheme -ly, the inability of adverbs to take complements follows automatically from the inability of attributive adjectives to take post-nominal complements extraposed across the noun, i.e., from their inability to form discontinuous (split) APs, as shown in (8) below.

| (7) | This man is proud of his daughter. |

| (8) | a. | *proud- of his daughter |

| b. | *a proud of his daughter |

Thus, the nominal analysis of -ly eliminates the necessity of a separate explanation for the inability of adverbs to take complements by reducing it to the inability of attributive adjectives to take extraposed post-nominal complements. By contrast, the suffixal analyses of -ly leave this fact about adverbs unexplained, and a generally accepted analysis of it has in fact been missing so far.3

This argument by Baker (2003) for the nominal analysis of -ly has been further developed and strengthened in Alexeyenko (2015). In particular, Alexeyenko points out that the generalization that adverbs cannot take complements is, in fact, not really correct. It has many counterexamples, such as, e.g., the following ones, which are often cited in the literature:

| (9) | Unfortunately for our hero, Rome burned. | (based on Jackendoff, 1977, p. 78) |

| (10) | a. | They will decide independently of my view. |

| b. | (John succeeded) independently from our efforts. (Alexiadou, 1997, pp. 5, 37) |

| (11) | Similarly to what Bob postulated, the shape of the universe seems to be muffin-like. |

| (Ernst, 2002, p. 30) |

Déchaine (1993, p. 70) also cites the following list of complement-taking adverbs, which are currently used predominantly in legalese:4

| (12) | agreeably to X, comfortably to X, concurrently with X, conditionally on X, differently from X, inconsistently with X, preferably to X, previously to X, subsequently to X, suitably to X |

At first glance, this fact could be used as counterevidence against Baker’s argument. In fact, however, the inability of attributive adjectives to take extraposed post-nominal complements is not unexceptional either, as has been shown, e.g., by Escribano (2005) in his comprehensive survey of discontinuous APs. Therefore, the question is rather whether the set of the base adjectives of complement-taking -ly adverbs coincides with the set of adjectives that can form discontinuous APs. If these sets coincide, this would only reinforce Baker’s argument for the nominal nature of -ly. In a novel observation, Alexeyenko (2015) has shown that these sets indeed coincide, and the data that have been used to demonstrate this will be discussed below.

First, the adjectival counterparts of the standardly cited complement-taking adverbs unfortunately, independently, and similarly, illustrated in (9)–(11), can all form discontinuous APs with post-nominal complements, as the examples in (13)–(15) from the BNC and the web demonstrate.

| (13) | a. | It was an unfortunate evening for me: I was knocked out in the second round, the only time I was knocked out, either at Eton or at Oxford. [BNC: H0A 873] |

| b. | It’s been a very unfortunate episode for all concerned. [BNC: HGM 1881] |

| (14) | a. | There are currently few, if any, civil society organisations in Vietnam that are in a position to give a truly independent opinion of the Government or the Communist Party.5 |

| b. | Roh was elected on the basis of his promises to reconcile with North Korea and take a more independent line from the United States.6 |

| (15) | a. | The three years I spent studying took a similar shape to my school years; on the surface I did well, passing my exams with seemingly not too much trouble. |

| [BNC: ADG 204] | ||

| b. | Along a different line of thought, Sherrington had thus reached similar conclusions to those of Pavlov in his famous conditioning experiments. | |

| [BNC: AMG 422] |

Furthermore, the same also holds for the base adjectives of Déchaine’s adverbs in (12); in fact, some of them occur among Escribano’s (2005) examples of felicitous discontinuous APs with post-nominal complements reproduced below.

| (16) | a subsequent article to Chomsky’s | |

| a previous version to this one | ||

| a prior attempt to Russell’s | ||

| a preferable solution to Chomsky’s | ||

| an alternative view to Chomsky’s | ||

| an analogous hypothesis to Abney’s | ||

| a comparable situation to ours | ||

| a different view from yours | ||

| an equivalent idea to that | ||

| a parallel theory to Frege’s | ||

| a separate room from ours | ||

| a similar car to mine | (Escribano, 2005, p. 566) |

The inverse holds too, as the adverbial counterparts of adjectives that can form discontinuous APs when used attributively, such as the ones in (16), can take complements as well. The examples below from the web illustrate this for some of the adjectives in (16) whose adverbial counterparts did not occur in earlier examples yet:

| (17) | a. | To get you to the product information you need as quickly as possible, we have a simple three step process. [...] Alternatively to the above process, if you exactly know what you’re after, then simply enter the product name and select the branch in the boxes at the left.7 |

| b. | Whilst Chomsky’s major achievement was to suggest that the syntax of natural languages could be treated analogously to the syntax of formal languages, so Montague’s contribution was to propose that not only the syntax but also the semantics of natural language could be treated in this way.8 | |

| c. | The Soviet Union did not admit until 1971 that Gagarin had ejected and landed separately from the Vostok descent module.9 |

By contrast, non-complement-taking adverbs, like the ones in Jackendoff’s examples in (2)–(6), have adjectival counterparts that cannot form discontinuous APs when used attributively, as shown below.

| (18) | a. | *a tired neighbor of the noise |

| b. | *a fearful king of a revolt | |

| c. | *an expressive manner of John’s needs | |

| d. | *a happy host that they were leaving | |

| e. | *an eager man to please |

Thus, there is a clear parallelism between -ly adverbs and specifically attributive adjectives with respect to their ability/inability to take complements. The analysis of -ly as a nominal morpheme modified attributively by the base adjectives of adverbs straightforwardly accounts for this parallelism. Furthermore, it makes it unnecessary to provide an independent explanation of why some adverbs cannot take complements that is different from the explanation of why some attributive adjectives cannot take extraposed post-nominal complements. By contrast, if -ly is analyzed as a suffix, either a derivational or an inflectional one, this parallelism between adverbs and only attributive adjectives, rather than adjectives in general, is unexpected and requires an independent explanation. A suffixal analysis of -ly also needs to explain why some adverbs cannot take complements, a question that lacks a satisfactory and generally accepted answer within this type of analysis.

2.1.2. Deletion Under Coordination

In the previous section, we have discussed a piece of evidence for the assumption that the adverbial marker -ly in English is a nominal root and the base adjectives of adverbs are its attributive modifiers. This section will present some further data, which also suggest that -ly is a root and not an affix, although they do not say anything about its categorial identity. These data, which have been introduced in Alexeyenko (2015) and have to do with the possibility of deletion under coordination, mirror an analogous argument made by Zagona (1990) with respect to the Spanish adverbial marker -mente. For this reason, I will discuss the Spanish data first.

The crucial observation in this connection is the fact that the adverbial morpheme -mente in Spanish is able to delete under coordination and in comparatives. The examples below from Zagona (1990) illustrate this for conjunction and disjunction.

| (19) | a. | inteligente y profundamente | |

| ‘intelligently and profoundly’ | |||

| b. | directa o indirectamente | ||

| ‘directly or indirectly’ | (Zagona, 1990) |

Zagona (1990) argues that this phenomenon, which is neither grammatically marginal nor dialectally restricted in Spanish, is an argument against the analysis of -mente as either a derivational or an inflectional suffix, because Spanish does not allow the elision of suffixes of either type, as shown by the following examples:

| (20) | a. | *industrializa- y modernización | |

| ‘industrialization and modernization’ | |||

| b. | *hablar- y escribiré | ||

| ‘I will say and write’ | (Zagona, 1990) |

By contrast, Spanish allows the elision of the heads of non-final compounds in a coordination of endocentric compounds with an identical head, such as in the examples in (21).

| (21) | a. | (países) centro y sudamericanos | |

| ‘Central and South American (countries)’ | |||

| b. | (datos) tanto macro como microeconómicos | ||

| ‘both macro- and micro-economic (data)’ | (Kovacci, 1999) |

Thus, with respect to deletion under coordination, -mente in Spanish patterns together with head constituents of compounds and not with suffixes, which suggests that adverbs formed by -mente are compounds as well and that -mente is a root, rather than a suffix.

Let us now turn back to English. A coordination of -ly adverbs with an elided -ly in the first part is generally not acceptable in English, as the ungrammaticality of the morphemic equivalent of (19-a) demonstrates:

| (22) | *intelligent- and profoundly |

In fact, however, deletion of the first -ly within adverb coordination is acceptable in some cases, e.g., in such phrases as direct and/or indirectly and fortunate or unfortunately, which are well attested. Below are some web examples from Alexeyenko (2015) in which the -ly-less conjunct/disjunct is unambiguously an adverb and which are almost certainly produced by native speakers.

| (23) | a. | Precisely because science deals with only what can be known, direct or indirectly, by sense experience, it cannot answer the question of whether there is anything—for example, consciousness, morality, beauty or God—that is not entirely knowable by sense experience.10 |

| b. | Surety Accountants shall not be liable for any damages either direct or indirectly resulting from the use of this site or the information contained on this site at any point in time.11 | |

| c. | Each of our direct and indirectly funded program areas was developed to meet a specific goal such as childcare quality, affordability, or capacity.12 |

| (24) | a. | I’m a Melbourne born and bred, fortunate or unfortunately I follow the AFL and yes I am a Collingwood supporter.13 |

| b. | Fortunate or unfortunately for you, you chose to live in a neighborhood that is in its rebirth phase.14 | |

| c. | The undertaking to which this series of lectures addresses itself is, it must be confessed, a pretentious one. There is involved, first the recognition that the wheel of destiny has turned. It has now come to a momentary pause, and the destinies of the world, fortunate or unfortunately, are placed in our surprised, reluctant and untrained hands.15 |

Furthermore, the deletion of -ly in the first conjunct under adverb coordination is also possible in phrases like nice and slowly or nice and steadily, as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer. The following examples from the BNC illustrate this.

| (25) | a. | I used sign language, and I worked on the assumption that all deaf people can lipread. So I mouthed the words nice and slowly. [BNC: CAP] |

| b. | She clamped her hand over her mouth and caught the sob, then forced herself to breathe nice and steadily, in, out, in, out – she wouldn’t panic. She wouldn’t! | |

| [BNC: JYB] |

The examples above show that the phenomenon of -ly deletion under coordination does exist in English, which, to my knowledge, has not been acknowledged in the literature before Alexeyenko (2015). Clearly, it is not comparably general and productive to -mente deletion in Spanish, being acceptable only in a restricted range of phrases. However, even in this case, -ly contrasts with both derivational and inflectional suffixes in English, which can never be elided in a similar way, cf. (26) and (27) below.16

| (26) | a. | *industrializ- and modernization |

| b. | *sex- and racist |

| (27) | a. | *walk- and talks |

| b. | *tall- and stronger |

| (28) | a. | black- or whiteboard |

| b. | pre- and post-modifiers |

Since head constituents of compounds, by contrast, can undergo deletion under coordination in English, as in (28), the data in (23)–(24) demonstrate that -ly patterns together with roots and not with suffixes, suggesting that it is a root itself, rather than a suffix.

Now that we have established the status of the morpheme -ly as a nominal root, the next section will discuss the analysis of -ly adverbs as a whole.

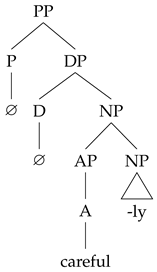

2.2. Internal Structure of -ly Adverbs as PPs

The previous section has argued that the morpheme -ly is a nominal root modified attributively by the base adjectives of adverbs, rather than a suffix. If -ly is a nominal morpheme, the next question is what adverbs are as a whole. They cannot possibly be compound nouns since adverbs do not have the distribution of nouns, as Torner (2005, pp. 120–121) rightly points out, using it as an argument against the nominal analysis of the Spanish adverbial marker -mente. However, the nominal analysis of -ly does not in fact necessarily imply that adverbs are nominal A–N compounds: it is also compatible with an alternative possibility that adverbs correspond to a larger morphosyntactic structure of a different category, in which the base adjective and -ly are embedded under further unpronounced material. In what follows, I will assume that the highest layer inside -ly adverbs is a PP projection (Alexeyenko, 2015; Baker, 2003; Déchaine & Tremblay, 1996), based on several considerations. First, this is plausible from a diachronic point of view insofar as the Proto-Germanic construction that -ly adverbs etymologically derive from featured an ablative or instrumental, i.e., oblique, case marking (see note 1 above). Second, and more importantly, adverbs and PPs (synchronically) have a near-identical distribution, which will be discussed in detail in Section 3.4.

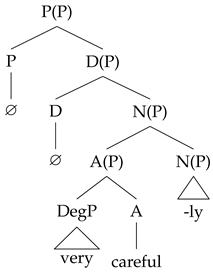

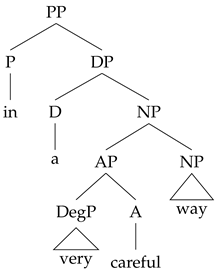

The structure in (29-a) below illustrates the gist of the analysis of adverbs assumed in this paper taking the manner adverb carefully as an example; the corresponding overt PP in a careful way is depicted in (29-b) for comparison. More specifically, I assume that the highest head in the structure of adverbs is a phonologically null but semantically non-vacuous prepositional head whose function is to relate the adverb to the relevant semantic argument of the expression that this adverb modifies, i.e., an event, a world, a time, a degree, etc., depending on the semantic class of the adverb. Furthermore, I also assume that this P head takes as its complement a DP in a usual fashion, which implies that it not only -marks that DP but also assigns Case to it. Note, finally, that although the present analysis treats adverbs as compounds, i.e., word-level formations (which is notationally often expressed by representing their phrasal nodes as minimal projections, s), the adjectives in the structure of adverbs can take modifiers and complements, cf. very differently from us (which may be taken to suggest that they are maximal projections, XPs). Because of this possible tension, the status of phrasal nodes in (29-a) has been left open (as indicated by the brackets), as it largely depends on what general framework of morphology is adopted, within which the present analysis is couched.17

| (29) | a. |  |

| b. |  |

Let us discuss two implications of this analysis of -ly adverbs. First, it implies that degree modifiers of adverbs, such as very in (29-a), are in fact degree modifiers of the underlying base adjectives. This means consequently that word boundaries do not reflect constituency in this case, as very and careful form a constituent but do not constitute a word unit, while careful and -ly, which form a word unit, are not a constituent to the exclusion of very. Moreover, the same holds for complements of adverbs, as in independently of my view. This mismatch between word boundaries and constituency in -ly adverbs is thus similar to the situation with the possessive clitic ’s and compounds like truck driver, for which it has been argued that the two roots combine before the suffix -er gets attached (cf. Harley, 2009):

| (30) | a. | [[ very careful ] -ly ] |

| b. | [[ truck drive ] -er ] |

Second, this analysis of adverbs implies that the internal structure of a manner adverb like carefully in (29-a) is identical with that of the corresponding manner adverbial in a careful way, see (29-b). The difference is only that the P and D heads in the structure of -ly adverbs are null and that the adjective–noun combinations are morphologically fused into single word units in them. Also other semantic classes of -ly adverbs have corresponding PP adverbials with the same internal structure, as the examples below demonstrate. They all contain semantically “light” nouns like manner, time, location, degree, etc., which are modified by the base adjectives of the corresponding -ly adverbs.18

| (31) | a. | He drives carefully. | (manner adverb) |

| ∼in a careful way/manner | |||

| b. | He fully understands the problem. | (degree adverb) | |

| ∼to a full extent/degree | |||

| c. | He regularly goes to the gym. | (frequency adverb) | |

| ∼on a regular basis | |||

| d. | He was briefly married. | (duration adverb) | |

| ∼for a brief time | |||

| e. | He lives centrally. | (location adverb) | |

| ∼in a central location | |||

| f. | He is financially independent. | (domain adverb) | |

| ∼from a financial point of view | |||

| g. | He will possibly get fired. | (modal adverb) | |

| ∼in a possible course of events |

The main semantic contribution of adverbs is conveyed by their base adjectives, which, according to the analysis argued for above, are linked semantically to the rest of the structure by the P head, whose semantics differs across various semantic classes of adverbs. The next question concerns the role played by the nominal morpheme -ly inside the structure of adverbs. Given that the base adjectives of adverbs have been argued to be attributive modifiers, the purpose of -ly can plausibly be related to the fact that the head nouns of attributive adjectives are required to be overt in English. This can be seen in examples like the ones below from Jackendoff (1971, p. 28), which show that the dummy element one must be inserted in the absence of a semantically full noun (see also Panagiotidis, 2003a, 2003b).19

| (32) | a. | I like Bill’s yellow shirt, but not . |

| b. | I like Bill’s yellow shirt, but not . |

Thus, I assume that -ly is a semantically empty dummy noun which is inserted because the base adjectives of adverbs require their head noun to be overt. In other words, the presence of -ly in adverbs is a manifestation of a more general constraint on the modified nouns of attributive adjectives in English.20

Finally, another question in connection with the proposed morphosyntactic analysis of adverbs concerns the fact that the P and D heads in their structure are null, which calls for legitimization. From a diachronic point of view, the absence of an overt prepositional element in -ly formations has to do with the fact that their ancestor construction in Proto-Germanic lacked an overt P element as well, although there are reasons to believe that it did contain a null one, given that the noun inside this construction was marked with an oblique case (ablative or instrumental, see note 1 above). The absence of an overt P head where it would be expected to be present also has other precedents in English, namely, in the case of so-called ‘bare-NP’ adverbs like that day or every way imaginable, a seminal analysis of which has been proposed in Larson (1985). Incidentally, Larson’s analysis is also related to (oblique) case, as it treats the nouns in the structure of bare-NP adverbs as inherently case marked. As for the D head assumed to be present in -ly adverbs, the reason for why it must be null may have to do with the fact that English does not have in its inventory overt determiners that are bound morphemes. Yet, this would be necessary for being able to form part of the compound structure together with the adjective and -ly.21

Now that a specific implementation of the PP analysis of adverbs has been proposed, it should be made clear that adopting the thesis that adverbs are PPs in disguise does not necessitate adopting the specific implementation of it presented in this section. Alternative analyses of the morphosyntactic structure of adverbs as PPs are possible as well and have in fact been proposed in the previous literature. The next section will discuss several such alternative possibilities comparing them with the present proposal.

2.3. Alternative Possibilities

As mentioned above, the general approach to adverbs that assimilates them with PPs does not necessarily imply that the specific analysis of their internal structure advocated in Section 2.2 has to be adopted. In what follows, I will discuss two alternative analyses that have been proposed in the literature and compare them with the present proposal.

One obvious alternative possibility within the PP approach to adverbs is to analyze the morpheme -ly as the P(-like) element that heads them, which has been entertained in Larson (1987). The scope of the analysis in Larson (1987) goes beyond the question of the internal structure of adverbs: its primary concern is adverb-headed free relative clauses in the context of the analysis of ‘bare-NP’ adverbs such as that day or every way imaginable proposed in Larson (1985). However, for the purposes of the comparison aimed at in this section, I will only discuss Larson’s treatment of -ly adverbs, which does not do justice to the entirety of his analysis of course.

The key premise of Larson’s (1987) approach to adverbs is the assumption that all [+N] categories are subject to the Case Filter, i.e., not just nouns, but also adjectives must be assigned Case if overt. Larson assumes that normally adjectives receive their Case in an indirect way via agreement with a nominal expression: the modified noun if they are used attributively or the subject of predication if they are used predicatively. However, this possibility of receiving Case via agreement is not available to adjectives in adjunct positions when they do not modify a noun. According to Larson, this is the case when adjectives function as verbal modifiers without being part of a PP. He suggests that the raison d’être of the morpheme -ly has to do precisely with this situation: being a P-like element, -ly has the function of assigning Case to APs and thus allowing them to act as verbal modifiers without violating the Case Filter. In other words, the relation between -ly and an AP is analogous to that between a P head and a DP. The internal structure of adverbs assumed by Larson is thus as below, where -ly’s status as an affix is presumably derived by Head Movement of A to Adv.

| (33) |  |

Let us now briefly compare this version of the PP approach to adverbs to that from Section 2.2. The crucial advantage of Larson’s analysis compared to the one advocated in this paper is that it does not need to assume the presence of null elements in the structure of adverbs, as it identifies the P head with the morpheme -ly and does not introduce any further null heads into the structure. The fact that diachronically -ly is of nominal origin is not a problem in this context: this fact cannot serve as an argument against its analysis as a P head synchronically because it is a well-attested grammaticalization path for nominal elements to develop into adpositional ones. Furthermore, Larson’s analysis is also compatible with the fact discussed in Section 2.1.2 that -ly can undergo deletion under coordination since regular P elements can do so too.

At the same time, however, a number of important questions remain open under this analysis, which concern the AP in the structure of adverbs. In its current form, this analysis does not assume anything special about this AP; i.e., it should be projected in a regular way, being able to host a specifier and a complement. Now, as far as the latter is concerned, it is not clear what could account for the restrictions on complement taking discussed in Section 2.1.1 under Larson’s analysis: all base adjectives of adverbs should be able to take complements as freely as predicatively used adjectives do. Moreover, also specifiers of adjectives, i.e., degree modifiers like very, present a potential challenge: after the A-to-Adv movement takes place, the rest of the AP will be linearized to the right of the newly formed complex head corresponding to the adverb, thus resulting in a wrong word order for all degree modifiers except for enough (e.g., *carefully very instead of very carefully). Hence, further movement operations will need to be assumed (and motivated) in order to derive the right linear order. Finally, the fact that this analysis allows APs to serve as prepositional complements may open the way to potential overgeneration with respect to their distributional properties, and hence their appearance in other argument positions will need to be restricted separately in this case.

Thus, the role attributed to the morpheme -ly in Larson’s analysis is that of a P-like element, i.e., an element that relates two different projections to each other syntactically and semantically. The idea that -ly is a linking element, though not an adpositional one, also underlies another analysis, which has been proposed in Corver (2005) and presents a different alternative to the approach taken in Section 2.2. It should be noted that also in the case of Corver’s proposal, the scope of the analysis is broader than the question concerning the internal structure of adverbs: it also aims to account for the inability of -ly-less adverbs to occur pre-verbally and the similarity of this fact to the impossibility for predicate inversion to take place in copula-less contexts. However, like before, the discussion below will be more narrow, being only concerned with Corver’s take on the morphosyntax of adverbs.

The crucial idea of Corver’s (2005) proposal is that the base adjectives of adverbs are linked to the rest of the structure by means of a predication relation, and the morpheme -ly realizes the predicational head that introduces it. The motivation for this idea comes from several facts. First, -ly is etymologically cognate with the similative lexical item like as in the example below, where it is used to establish a predication relation between the subject and the predicate nominal.

| (34) | Mary was like a daughter (to Bill). |

Second, Corver observes that in Welsh the adverbial and the predicational markers are realized by one and the same lexical item yn, as shown in the following examples:22

| (35) | Mae Gwyn yn ddiog. | |

| be.pres.3sg G. pred lazy | ||

| ‘Gwyn is lazy’. | (Borsley et al., 2007, p. 43) |

| (36) | Gwelais i yn sydyn ] blismyn yn y stryd. | |

| see.past.1sg 1sg pred sudden policemen in the street | ||

| ‘I suddenly saw policemen in the street’. | (Borsley et al., 2007, p. 226) |

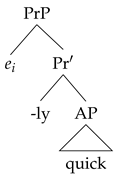

Based on these facts, Corver suggests that -ly realizes the predicative head Pr in the sense of Bowers (1993), which predicates the adverb’s base adjective of a null pro-form coindexed with the event argument (in the case of VP-modifying adverbs), as shown in the structure below for quickly. Thus, according to this analysis, an adverb as a whole is assumed to spell out a PrP inside which the Head Movement of A to Pr, i.e., to -ly, takes place.

| (37) |  |

The key question this analysis leaves open is the same one as in the case of Larson’s approach discussed before: the AP in the structure of adverbs is explicitly assumed to be a predicative one in Corver’s analysis, which predicts there to be no restrictions as far as the ability of adverbs to take complements is concerned, contrary to fact. In addition, the assumption that adverbs are put together morphologically through Head Movement of their base adjectives to -ly does not derive the right linear order for degree modifiers (as discussed above), which has in fact been first observed by Corver in connection with his own analysis. In reaction to this observation, he proposes a modification of the analysis according to which -ly is merely a case inflection on the adjective obtained because of the Case-assigning capacity of the now null Pr head. However, this makes the resulting analysis lose some of its appeal compared to the approach pursued in the present paper by introducing null elements into the internal structure of adverbs.

Thus, the discussion in this section reveals that the analysis of the internal structure of adverbs presented in Section 2.2 has empirical advantages over its alternatives within the family of PP analyses. For this reason, it is opted for in this paper, even if it assumes adverbs to contain null elements in their structure. In the next section, I will proceed to an evaluation of this analysis in comparison with its alternatives that are more radically different from it in that they do not assume adverbs to be PPs. It will be shown that the proposed analysis is also able to account for the facts that have been used as arguments for those alternatives.

3. Accounting for the Arguments from the Standard Analyses

The aim of this section is to present some of the facts that have been used as arguments in favor of the more standard analyses of -ly as an inflectional or a derivational suffix and in this way to also indirectly present these analyses themselves. As a matter of fact, all the arguments discussed below have been put forth to support the inflectional analysis of -ly, with the exception of one, namely, the distribution of adverbs, which will be discussed in detail in Section 3.4. More precisely, the commonly assumed complementary distribution of adverbs and adjectives has also traditionally been used as evidence for the inflectional analysis; more recently, however, it has been argued not to hold, which speaks in favor of the derivational analysis. Against this background, the goal of this section is to show that all of these facts that have been used in support of the suffixal analyses can in fact also be accounted for by the PP analysis of adverbs advocated in this paper. At the same time, however, some questions that are potentially problematic for the PP analysis do remain open; these will be discussed in conclusion in Section 3.5.

3.1. Degree Modifiers

One of the facts that has been used as evidence for the analysis of -ly as an inflectional suffix, i.e., for the assumption that adjectives and adverbs belong to a single major category, concerns the elements that can serve as their modifiers. In particular, adjectives and adverbs share all their degree modifiers, including those that form analytic comparatives and superlatives, and no other category permits exactly the same range of degree modifiers as them (cf. Emonds, 1976, pp. 12–13; Emonds, 1985, p. 162).

| (38) | painful/painfully |

| (39) | painful/painfully |

This fact follows straightforwardly on the PP analysis of adverbs advocated in this paper because this analysis implies that degree modifiers of adverbs are in fact modifiers of adjectives present in their structure, as (29-a) shows.

3.2. Degree Morphology

Next, -ly adverbs do not form synthetic comparatives and superlatives even in cases in which it should be morphophonologically and semantically possible. More concretely, the comparative/superlative morphology (-er/-est) can attach neither to -ly nor to the base adjectives of adverbs, as the following examples show:

| (40) | a. | *quicklier/*quickerly |

| *quickliest/*quickestly | ||

| b. | *nicelier/*nicerly | |

| *niceliest/*nicestly |

This fact has also been interpreted in favor of the inflectional analysis of -ly. In particular, if -ly is an inflectional suffix, it can be argued to be mutually exclusive with -er/-est because they are both inflectional, while English allows only one inflectional suffix per word (cf. Hockett, 1958, p. 210).

However, this fact can also be accounted for by the PP analysis of adverbs. Specifically, the inability of comparative/superlative morphology to attach to -ly (*quicklier) can be explained as the inability of degree morphology to attach to nouns, while its inability to attach to the base adjectives of adverbs preceding -ly (*quickerly) can be explained insofar as degree morphology is inflectional in its nature, but compounding generally operates on uninflected stems in English.23

3.3. Further Derivational Suffixation

Finally, another fact that has been used as an argument in favor of the inflectional analysis of -ly is that -ly adverbs do not allow for further derivation by suffixation (Plag & Baayen, 2009). For instance, forms like *quicklyish, *quicklitude, *quickliment, etc., cited in Payne et al. (2010, p. 62), do not exist, i.e., -ly acts as a closing morpheme. If -ly is an inflectional suffix, this fact receives a straightforward explanation because derivational morphology generally does not apply to inflected forms; in other words, derivation generally precedes inflection in English.

Within the PP analysis of adverbs, the fact that -ly adverbs resist further derivation by suffixation can be accounted for by appealing to the inability of the corresponding PP adverbials like the ones listed in (31) to participate in derivation by suffixation. Forms like *in-a-careful-way-ness, *to-a-full-extent-ish, or *from-a-financial-point-of-view-hood are unavailable, although derivational suffixes can attach to phrasal bases in general and to PPs in particular, as evidenced by such examples from the COCA as above-averagehood, out-of-towner, over-the-topism, at-homeness, etc. reported in Bauer et al. (2013, pp. 513–514).24

3.4. Syntactic Distribution of Adverbs

The last point of discussion in this section concerns the distribution of adverbs, which has also played an important role for the inflectional analysis of -ly. The central fact in this connection is that adverbs can serve as modifiers of all categories but nouns, being able to modify verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, and PPs. Moreover, they can only act as modifiers, but not as independent predicates, i.e., they cannot occur in the predicative position.

| (41) | a. | a {painful/*painfully} wound | nouns |

| b. | to injure {*painful/painfully} | non-nouns | |

| {*painful/painfully} honest | |||

| {*painful/painfully} slowly | |||

| {*painful/painfully} behind the times |

| (42) | This wound is {painful/*painfully}. |

In both of these respects, adverbs appear to be in complementary distribution with adjectives, which can only modify nouns and can be used predicatively. This fact has served as an argument for treating adverbs and adjectives as belonging to a single major lexical category (and, accordingly, for treating -ly as an inflectional suffix), because elements in systematic complementary distribution are generally analyzed as sub-classes of the same distributional class (cf. Radford, 1988, pp. 139–141).

However, the claim that adjectives and adverbs are in complementary distribution has been questioned by Payne et al. (2010). In particular, Payne et al. (2010) show that, even though adverbs cannot pre-modify nouns, they can post-modify them. Some of their examples that illustrate this are given below.

| (43) | a. | In view of your decision regarding Burma the British Government was not making any formal request to you for [the use temporarily of Australian troops to defend Ceylon]. |

| b. | Public awareness of the low birthweight problem is heightened by [the release periodically of major reports by a variety of public and private organizations interested in maternal and child health]. | |

| c. | [The unique role globally of the Australian Health Promoting Schools Association], as a non-government organization specifically established to promote the concept of the health promoting school, is described. | |

| d. | During the early 1990s [a timber shortage internationally] led to an increase in timber prices and export opportunities for premium timber grades. |

The post-nominal adverbial modification of deverbal event nouns like use and release in (43-a) and (43-b) can potentially be argued to target verbal projections inside the morphosyntactic structure of these nouns (cf. Fu et al., 2001). Importantly, however, Payne et al. (2010) show that adverbs can modify post-nominally also non-deverbal nouns like role and shortage in (43-c) and (43-d). Since such nouns cannot be assumed to contain verbal projections in their internal structure, it must be the NP itself that is modified in this case.25

The data in (43) show that the standard assumptions about the distribution of adverbs in English need to be updated. In addition to being non-noun modifiers (i.e., modifiers of verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and PPs), adverbs can also act as post-nominal modifiers of nouns, though they cannot modify nouns pre-nominally. Finally, they cannot occur in the predicative position, as we have seen before. Therefore, if adverbs are to be assimilated with the category of PPs, as argued in this paper, it needs to be shown that they share this distribution with PPs (and that all potential differences, should there be any, can be attributed to independent factors). In what follows, we will see that this is indeed the case; the sections below will discuss in turn different aspects of the distribution of adverbs and PPs to show it.

3.4.1. Modification

First, let us consider non-nominal modification. We have seen before that adverbs are able to modify verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, and PPs; the relevant examples illustrating this are repeated again below.

| (44) | to injure painfully |

| painfully |

Obviously, PPs can modify elements of all these categories too, as the following examples show.

| (45) | to injure in a painful way |

| in a painful way |

Thus, with respect to non-nominal modification, adverbs and PPs have the same distribution. One difference between them in this connection is the fact that, unlike adverbs, PPs tend to be placed after the element they modify. This is, however, not a strict requirement and has likely to do with relative prosodic weight rather than syntactic factors.

Second, as far as nominal modification is concerned, we have seen that adverbs cannot serve as pre-nominal modifiers of nouns but can modify them post-nominally, as shown by the data from Payne et al. (2010) discussed above. The same also holds for PPs; this is illustrated in comparison with adverbs by the examples below.26

| (46) | a. | *an internationally timber shortage |

| b. | a timber shortage internationally |

| (47) | a. | *an across the world timber shortage |

| b. | a timber shortage across the world |

This shows that, also with respect to nominal modification, adverbs and PPs share their distribution.

3.4.2. Predication

Next, let us consider the ability to occur in the predicative position. We have seen before that adverbs cannot be used predicatively; the relevant example is repeated below for convenience.

| (48) | *This wound is painfully. |

At first glance, it may appear that adverbs actually do not match the distribution of PPs in this respect, being able to occur predicatively, as the following examples demonstrate:

| (49) | a. | Your box is under the table. |

| b. | Our meeting is in the afternoon. |

However, even though some PPs, in particular locative and temporal ones, can be used predicatively, most PPs cannot. The examples below illustrate this for some of the PPs from (31).

| (50) | a. | *His driving is in a careful way. |

| b. | *His understanding of the problem is to a full extent. | |

| c. | *His independence is from a financial point of view. |

Moreover, some adverbs are in fact able to occur in the predicative position, as the following web example demonstrates for the temporal adverb recently:

| (51) | My birthday was recently and as I pondered my new age I realized that the cumulation of my years was beginning to catch up with me.27 |

If PPs are assumed to be in general able to appear predicatively, the ungrammaticality of the examples in (50) is difficult to explain. But if it is assumed that PPs generally cannot occur in the predicative position (i.e., as complements of Pred, cf. Bowers, 1993), it could be argued that examples like in (49) (and (51)) are in fact not instances of predication: the verb be may be argued to be a lexical verb in such cases, as suggested by its interpretation as ‘be located’ in (49-a) and ‘happen/occur’ in (49-b) (and (51)), rather than an auxiliary verb associated with Pred whose function is to carry tense/aspect and agreement morphology. This possibility receives support from the fact that PPs cannot be selected by Pred in languages with a phonologically overt Pred, such as Edo and Chichewa. Instead, a lexical verb with locative/posture meaning or the verbal copula must be used in this case, as has been shown by Baker (2003, pp. 314–315), whose examples from Edo and Chichewa are given below.

| (52) | Edo | ||

| a. | *Òzó (yé/rè) vbè òwá. | ||

| Ozo pred at house | |||

| ‘Ozo is in the house’. | |||

| b. | Òzó rré òwá. | ||

| Ozo is.at house | |||

| ‘Ozo is in the house’. | [locative verb] | ||

| c. | Òzó mùdìá yè esuku. | ||

| Ozo stand at school | |||

| ‘Ozo is at school’. | [posture verb] |

| (53) | Chichewa | ||

| a. | *Ukonde ndi pa-m-chenga. | ||

| net pred on-3-beach | |||

| ‘The net is on the beach’. | |||

| b. | Ukonde u-li pa-m-chenga. | ||

| net 3S-be on-3-beach | |||

| ‘The net is on the beach’. | [verbal copula] | ||

Therefore, if it is assumed with Baker (2003) that PPs cannot serve as complements of Pred, this means that their distribution is identical with that of adverbs also in this respect.

3.4.3. Inversion

Another distributional fact that should be discussed in connection with adverbs and PPs concerns the ability to participate in locative/directive inversion.28 As is well known, PPs in English can participate in this type of inversion, which is illustrated by the examples below.

| (54) | a. | In the coffee shop sat a man. |

| b. | Into the room came two students. |

Adverbs are, in fact, able to participate in it too, as the following examples from the web demonstrate:

| (55) | a. | Roughly centrally lay a circular narrow-ditched house.29 |

| b. | Then slowly appeared a large float being carried by strong men.30 |

Hence, also with respect to locative/directive inversion, the distributions of adverbs and PPs match.

All in all, the PP analysis of adverbs is thus able to account for the fact that adverbs and PPs share their distribution, which the inflectional and the derivational analyses fail to capture. Note also that if adjectives and adverbs were in a complementary distribution, as is commonly assumed, this fact in itself would be unexpected and surprising on the analysis of adverbs as PPs, because it does not predict any distributional relations to hold between adverbs and adjectives, and would therefore call for an explanation. Since, however, it has been shown to not be the case, this issue does not arise.

3.4.4. Coordination

The final fact about the distribution of adverbs that I will discuss here concerns their ability to be coordinated with PPs.31 Coordinability has served as a powerful diagnostic for the categorial identity of syntactic elements because it is subject to a constraint which requires the coordinands to be of the same category, sometimes referred to as the Law of the Coordination of Likes (cf. Williams, 1981). The examples below, cited after Sag et al. (1985, p. 118), illustrate this constraint; note that it is the coordination that causes a problem in these examples since each of the coordinands on its own is grammatical in the same environment.

| (56) | a. | *The scene of the movie and that I wrote was in Chicago. | |

| (Chomsky, 1957, p. 36) | |||

| b. | *John sang beautifully and a carol. | (Peterson, 1981, p. 449) | |

The crucial fact in this context is the well-known observation that adverbs and PPs can be coordinated, as the following examples show:

| (57) | a. | Packages will be arriving at two o’clock and subsequently. | |

| (Larson, 1985, p. 608) | |||

| b. | We walked slowly and with great care. | (Sag et al., 1985, p. 140) | |

This fact (along with several similar ones) has been regarded as a surface violation of the Law of the Coordination of Likes, which makes it necessary to introduce some further assumptions in order to maintain this constraint on coordination. Under the PP analysis of adverbs, however, it straightforwardly fits into the picture. Moreover, if the Law of the Coordination of Likes is assumed to be indeed a valid principle, the fact that adverbs can be coordinated with PPs provides further evidence for the analysis of adverbs as PPs. By contrast, the derivational and inflectional analyses of adverbs need to provide a separate explanation of this fact, since it is not immediately clear in this case why adverbs, being elements of an independent category (either on their own or together with adjectives), should be coordinable with PPs, i.e., members of another category.

3.5. Open Questions

This section concludes the overview of what the PP analysis of adverbs can account for by discussing three issues that present potential problems for it and require an explanation. Note that these issues have not been used as arguments for the alternative, affixal analyses of adverbs in the previous literature, but it is indeed more straightforward to account for them if -ly is analyzed as a suffix.

The first issue concerns adjective stacking and coordination.32 More specifically, it has to do with the fact that base adjectives of adverbs cannot be stacked or coordinated, while adjectives inside the structure of their PP counterparts like in (31) of course can:

| (58) | a. | in a slow careful way |

| b. | in a slow and/but careful way |

| (59) | a. | *slowcarefully |

| b. | *slow-and-careful-ly |

Given that the PP analysis attributes to adverbs the same internal structure as that of adverbial PPs, this fact is unexpected. Intuitively, the reason for why adverbs resist further internal syntactic complexity has to do with the fact that, unlike regular PPs, they form single word units in morphology, which imposes limits on purely syntactic processes like adjective stacking or coordination. However, the formulation of the relevant constraints that are at work in this case remains an open issue for now.

The second issue has to do with the placement of the degree modifier enough in the context of adjectives and adverbs.33 Recall the following pair of examples, which have been used in Section 2.1.1 as an argument for the nominal nature of -ly:

| (60) | a. | *proud- of his daughter |

| b. | *a proud of his daughter |

The logic of the argument has been that if -ly is a nominal element modified attributively by the base adjective of the adverb, then the inability of adverbs like proudly to take complements can be reduced to the inability of their base adjectives to form split APs with extraposed post-nominal complements.

Now, this logic can also be applied to the degree modifier enough, since, unlike other degree modifiers in English, it does not precede but follows the adjectives it modifies. Moreover, crucially, it also does not allow the formation of split attributive APs in which it would be placed to the right of the modified noun, being linearly separated from the adjective by it, cf. (61-b). Given this fact, the nominal analysis of -ly predicts that the same pattern should also obtain in the case of adverbs. This is, however, not the case: adverbs can be modified by enough, as (61-a) demonstrates.

| (61) | a. | proud- enough |

| b. | *a proud enough |

Thus, the data concerning the placement of enough seem to suggest the opposite conclusion with respect to the status of -ly as compared to complement extraposition, and would require an independent explanation in order to uphold the PP analysis of adverbs. I leave this as an open question for future research.34

Finally, the third issue concerns the fact that -ly does not display some properties of nominal expressions. In particular, it cannot take complements, differing in this respect from nouns like way in the structure of the corresponding PP adverbials, as the examples below show:

| (62) | a. | in an elegant way [of a real gentleman] |

| b. | *elegantly [of a real gentleman] |

There may be various ways of accounting for the contrast above. On the one hand, it can be assumed that -ly does not project a phrasal node because it is part of a compound structure and, for this reason, it cannot take complements. However, it is unclear in this case why the base adjectives of adverbs are different from -ly in this respect, being able to take complements (see Section 2.2). On the other hand, it can also be assumed that -ly has undergone a certain degree of grammaticalization, which has resulted in the loss of some nominal properties. However, the question is in this case which functional element it is that -ly got (partially) reanalyzed into. The grammaticalization path of -ly could plausibly be assumed to go in the direction of an adposition or a case marker, but this analysis will face the problems discussed in Section 2.3 in connection with the approaches proposed in Larson (1987) and Corver (2005). In view of the complexity of these issues, I leave them open for now, awaiting further research.

4. Compositional Semantics

Now that we have discussed various morphosyntactic facts that speak in favor of (or at least are compatible with) the analysis of adverbs as PPs, let us turn to another aspect of adverbs that plays well together with this analysis: their semantics. In what follows, I will illustrate this on the basis of manner and degree adverbs, but analogous claims can be made for other semantic classes of adverbs as well.

4.1. Manner Adverbs

For the purposes of modeling the semantics of manner adverbs, I will quite standardly adopt the framework of event semantics. Within this framework, it is usually assumed that manner adverbs denote properties of events, which are co-predicated of the core event argument along with the properties of events denoted by the main verbs. The morpheme -ly is typically not attributed any semantic contribution in this case, such that the event predicate in the denotation of a manner adverb simply corresponds to its base adjective (cf. Landman, 2000; Parsons, 1990), as illustrated below for carefully.

| (63) | 〚carefully〛 = |

However, contrary to this analysis, there is a growing body of literature that argues that manner modification should involve predication over manners rather than events, which can be modeled either as a separate basic semantic type (Alexeyenko, 2015; Dik, 1975; Piñón, 2007; Schäfer, 2008, 2013) or as event kinds (Gehrke, 2015; Gehrke and Castroviejo, 2015; Landman, 2006; Landman and Morzycki, 2003). Within this kind of approach, the semantics of manner adverbs has to be more complex than just a manner predicate though: in addition, it must also contain a quantifier over manners and a relation that links manners to events, i.e., be along the lines of (64).35

| (64) | 〚carefully〛 = |

Without any morphosyntactic decomposition of adverbs, it seems to be even more stipulative to assume that manner adverbs introduce all this semantic material into the logical form than to just ignore -ly semantically as in (63). Against this background, Alexeyenko (2015) argues that the semantics in (64) can in fact be derived fully compositionally if the PP analysis of adverbs advocated in this paper is adopted. Below, I will outline this compositional semantics.

For ease of exposition, let me first repeat the proposed morphosyntactic structure of adverbs from Section 2.2:

| (65) |  |

Given this morphosyntax, it is natural to assume that the base adjectives of manner adverbs contribute just the relevant properties of manners, as (66-a) illustrates (the semantics of gradability being left out for simplicity). As far as the semantic contribution of -ly is concerned, it has been argued in Section 2.2 that this morpheme is a semantically empty dummy noun inserted for syntactic reasons. In formal semantic terms, this means that it denotes a generic predicate that does not narrow down the relevant domain, such as, e.g., in (66-b). The composition of these two denotations by means of Predicate Modification (Heim & Kratzer, 1998) yields the semantics in (66-c) for the higher NP in the structure above.

| (66) | a. | 〚careful-〛 = λm.careful(m) |

| b. | 〚-ly〛 = λm.manner(m) | |

| c. | 〚NP〛 = λm.[careful(m) ʌ manner(m)] |

Now, instead of loading the denotation of the base adjective with it, the rest of the semantics in (64) can be contributed by the P and D heads in the structure of manner adverbs. In particular, the D head introduces the (existential) quantifier over manners, while the P head is responsible for linking manners to the event structure; crucially, both of them are natural loci for this type of semantics. To simplify matters, I will use the type-adjusted version of the indefinite determiner in (67-a), rather than the more standard generalized quantifier version: this allows its interpretation in situ and avoids Quantifier Raising, but nothing important hinges on this. The denotation of the P head is given in (67-b); it introduces the partial -role-like manner function, which maps events onto manners. In other words, the P head plays here an analogous role to the prepositions in other adverbial PPs that introduce optional -roles, such as, e.g., the instrumental with in with a hammer, which can be plausibly analyzed as denoting .

| (67) | a. | 〚D〛 = λQ.λP.λe.∃m [P(m)(e) ∧ Q(m)] |

| b. | 〚P〛 = λm.λe.manner(m)(e) |

Putting all the pieces together, we arrive at the following semantics for the entire PP, which in a next step will be able to combine with the verb denotation by means of Predicate Modification:

| (68) | 〚PP〛 = |

The semantics above is exactly what we wanted to have as the meaning of manner adverbs in (64), and it has been derived in a completely compositional way without making any unmotivated assumptions. In this sense, the PP analysis makes it possible to have a straightforward mapping between the morphosyntax and the semantics of manner adverbs.

Moreover, it is not difficult to see how comparable compositional analyses of adverbs belonging to other semantic classes can also be entertained in a straightforward way thanks to the presence of the P and D heads in the structure. To illustrate this, I will spell out the compositional semantics for another common adverbial class, namely, degree adverbs like extremely.

4.2. Degree Adverbs

In order to be able to discuss possible analyses of the semantic contribution of degree adverbs, some basic assumptions regarding the semantics of gradability need to be introduced first. For the purposes of the present discussion, I will quite standardly assume the degree-based approach to the semantics of gradable predicates (Cresswell, 1976; Kennedy & McNally, 2005; von Stechow, 1984). According to this approach, degrees constitute a separate basic semantic type, which allows the modeling of the semantics of gradable predicates as denoting relations between individuals and degrees, as shown below for the gradable adjective tall.

| (69) | 〚tall〛 = |

The degree argument of such predicates can be saturated by a measure phrase such as two meters in two meters tall. However, in the absence of a measure phrase, the unmodified positive form of gradable adjectives is usually assumed to contain an additional null morpheme pos, whose denotation is given below (cf. Morzycki, 2016, p. 115). In prose, the role of pos is to introduce an existentially bound degree variable along with a contextually specified standard of comparison for the relevant property and state that the degree in question exceeds the standard of comparison.

| (70) | 〚pos = |

A common assumption about degree modifiers like very or extremely is that they occupy the same position as pos and also contribute the same semantics, except they do not merely state that the relevant degree just exceeds the standard of comparison but that it exceeds it significantly. Thus, the following denotation of very from Morzycki (2016, p. 119) features the significantly-greater-than relation ≫ in place of the greater-than relation > from the denotation of pos.

| (71) | 〚very = |

In this connection, Morzycki notes that the semantics above can also be expressed in other ways, including by predicating of the difference between the relevant degree and the standard of comparison, as shown below:

| (72) | 〚very = |

This latter formalization is particularly convenient as a template for the denotations of degree adverbs like extremely, moderately, unnoticeably, etc., because the predicate can be just substituted with the predicates corresponding to the base adjectives of these adverbs, all the rest remaining the same. Thus, for instance, the adverb extremely receives the following denotation under this type of analysis:

| (73) | 〚extremely = |

We can now see how this semantics can be derived in a compositional way based on the PP morphosyntax of adverbs advocated in this paper, i.e., under the assumption that extremely has the same internal structure as carefully in (65) above. The semantic contributions of the base adjective and -ly in the structure of extremely can be treated analogously to what has been assumed earlier in the case of manner adverbs, with the difference that the relevant predicates now range over degrees and not over manners, as shown below.36

| (74) | a. | 〚extreme-〛c = λdΔ.extremec(dΔ) |

| b. | 〚-ly〛c = λdΔ.degree(dΔ) | |

| c. | 〚NP〛c = λdΔ.[extremec(dΔ) ∧ degree(dΔ)] |

In the next step, the existential quantifier introduced by the D head closes off the degree argument of the NP, creating a generalized quantifier over degrees:

| (75) | 〚DP = |

Finally, the role of the P head is to introduce a degree variable, which later on will be identified with the degree argument of the adjective modified by extremely, as well as the standard of comparison, and to compute the difference between the two. Like in the case of manner adverbs, I will for simplicity avoid Quantifier Raising, interpreting everything in situ: for this reason, the denotation of the P head is adjusted such that it can take as an argument a generalized quantifier over degrees, rather than a degree. Nothing important hinges on this, however.

| (76) | 〚P = |

Altogether, this yields the following semantics of the entire PP, which is equivalent to what we wanted to arrive at as the denotation of extremely, cf. (73) above.

| (77) | 〚PP = |

Summing up, in this section, we have spelled out a possible compositional semantics for two varieties of adverbs under the PP analysis of their morphosyntax: manner adverbs and degree adverbs. These two types of adverbs differ from each other non-trivially semantically given that manner adverbs are optional event modifiers, while degree adverbs introduce an obligatory component of the semantics of the positive form of gradable adjectives in the absence of pos. The discussion above thus shows that the PP analysis is powerful enough to accommodate compositional adverbial semantics from different semantic domains.

5. A Cross-Linguistic Outlook

This paper has been concerned with the status of adverbs as a category specifically in English, and it has been argued that they do not need to be distinguished into a separate lexical category but can be assimilated with PPs. The identification of the inventory of categories available in a language is arguably a language-internal issue and thus the question of whether adverbs constitute a separate lexical category in English should not have an immediate bearing on this question for other languages. Nevertheless, the question concerning how adverbs as a category stand in a broader cross-linguistic perspective is still a valid one, particularly given the scarcity of work in this domain (but see Hallonsten Halling, 2018). For this reason, I will conclude this paper by providing in this section a first preliminary outlook into the kinds of lexical items and constructions that are used in the languages of the world to serve the function similar to that of adverbs in English.

Let us start the discussion with languages closely related to English from the Indo-European language family, in which adverbs have also been traditionally distinguished into a separate lexical class. For a number of languages from this family, the approach of assimilating adverbs with PPs has in fact been advocated in the previous literature. In particular, this holds for Germanic languages other than English (Waldenberger, 2015), Romance languages (Déchaine & Tremblay, 1996; Kovacci, 1999; Zagona, 1990), and Slavic languages (Caha & Medová, 2009; Kariaeva, 2009; Rozwadowska, 2011). As far as the marking of adverbs in these languages is concerned, they either have a dedicated adverbial marker (Romance) or are zero- or default-marked forms of adjectives (Germanic and Slavic).

The PP analysis of adverbs would also be plausible for a number of languages from other language families because of the presence of overt adpositional/case morphology on adverbs in them. This is the case, for instance, in Uralic languages, and PP analyses of adverbs in Finnish and Hungarian have in fact been proposed in the literature (Kádár, 2009; Manninen, 2003). A similar situation with adverbs is also found in Hebrew (Semitic), which makes the PP analysis a plausible option in this case as well (cf. Ravid & Shlesinger, 2000).37 For a discussion of some other languages to which this analysis could potentially also be applied, see Baker (2003, pp. 236–237).

Finally, in what follows, I will discuss some strategies employed by the languages of the world to express what corresponds to adverbs in a language like English. One possibility in this connection is to make use of “adjectival” forms in the adverbial function as well, with no special marking in addition. This strategy is used by Germanic languages (for instance, German), as already mentioned above, but also by languages like Paraguayan Guarani (Tupian), where unmarked roots can serve as both adnominal (78) and adverbial (79) modifiers.

| (78) | ko yvyra tuicha | |

| this tree big | ||

| ‘this tall tree’ | (Estigarribia, 2020, p. 15) |

| (79) | Tuicha ñane-pytyvõ-ta. | |

| big 1pl.incl.inact-help-fut | ||

| ‘It will help us greatly’. | (Estigarribia, 2020, p. 191) |

Another strategy consists in adding case morphology to “adjectival” elements, which is employed, for instance, in Kalaallisut, also known as West Greenlandic (Eskimo-Aleut). Kalaallisut lacks a morphologically distinct category of adjectives; elements corresponding to attributive adjectives in English are verbal forms with intransitive participial morphology (80). It is these forms that are used in the most common way of forming adverbs in the language, through the addition of instrumental case marking (81).

| (80) | inuit pikkuris-su-t | |

| people be_clever-intr.ptcp-pl | ||

| ‘clever people’ | (Fortescue, 1984, p. 108) |

| (81) | Uummanna-mi ajunngit-sur-suar-mik piniqar-pugut. | |

| U.-loc be_good-intr.ptcp-big-ins be_treated-1pl.ind | ||

| ‘We were treated very well in Uummannaq’. | (Fortescue, 1984, p. 100) |

Finally, another cross-linguistically common way of creating adverbs is, of course, by means of dedicated adverbial marking. This is the strategy employed in English, but also in Romance languages, as mentioned above. I will additionally illustrate this strategy here with Welsh (Celtic), where adverbs are formed through a special adverbial marker yn, which precedes the adjective, as the following examples show:38

| (82) | Clywodd Emyr y canu hyfryd. | |

| hear.past.3sg E. the singing pleasant | ||

| ‘Emyr heard the pleasant singing’. | (Borsley et al., 2007, p. 70) |

| (83) | Dylai Rhiannon ganu *(yn) hyfryd. | |

| ought.cond.3sg R. sing.inf pred pleasant | ||

| ‘Rhiannon ought to sing pleasantly’. | (Borsley et al., 2007, p. 70) |

It is the languages that make use of this latter strategy that present particular interest in the context of the approach of dispensing with a separate category of adverbs, which has been advocated in this paper for English. Should it turn out that adverbs can be reduced to some other category in the majority of cases in a broader typological perspective, this would be a striking fact that calls for an explanation. For now, this question remains open for future research.

6. Conclusions

The goal of this paper has been to show that the grammatical theory of English does not need to distinguish a separate lexical class of adverbs. Rather, they can be assimilated with the category of PPs, with which they share their syntactic distribution. This paper has provided an overview of the arguments for the PP analysis of adverbs, and it has also shown that the facts that have been previously interpreted as arguments for alternative approaches can also be accounted for by it. Finally, it has identified several issues that are potentially problematic for the PP analysis and require further research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments on this work. Special thanks go to the guest editors of this special issue: Norbert Corver, Lex Cloin-Tavenier, and Marta Massaia. More specific suggestions and comments are acknowledged within the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | More precisely, it derives from its form -lîko- with the suffix -ô, which is presumably the ending of the ablative feminine/neuter or the instrumental neuter fulfilling an adverb-forming function (see the etymology section of the Oxford English Dictionary entry for the adverbial -ly, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/9533308717 (accessed on 10 November 2024), as well as references in Corver (2005)). Thus, -ly is cognate with such nouns as Leiche ‘corpse, dead body’ in German and its obsolete English counterpart lich. |

| 2 | The analysis argued for in this paper in Section 2.2 implies that there is no such thing as ‘complements of adverbs’, rather it is their base adjectives that take complements extraposed across the nominal element -ly. For simplicity, I will however still continue using this phrase in a pre-theoretic sense. Note also that the discussion below concerns specifically complements and not adjuncts of adverbs/adjectives, because adverbs can generally take adjuncts (cf. *happily at their departure vs. happily for us), while adjuncts of pre-nominal adjectives can be extraposed across the modified noun (cf. a happy day for our family). |

| 3 | In a well-known analysis, Travis (1988) has argued that adverbs cannot take complements because they do not project to a phrasal category, but remain as heads. However, the head analysis of adverbs is problematic insofar as adverbs can take modifiers and, in fact, sometimes even complements, as will be discussed below (see alsoAlexiadou, 1997, § 2.3.2, for a discussion of this issue). |

| 4 | Note that Déchaine uses the fact that some adverbs can take complements as an argument for the approach to adjectives and adverbs as positional variants of a single category (see also the discussion in Vinokurova, 2005, § 4.6). |

| 5 | https://web.archive.org/web/20160625143040/https://www.eeas.europa.eu/vietnam/csp/nip_05_06.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 6 | https://www.npr.org/2007/12/20/17330572/lees-economic-pitch-finds-following-in-south-korea (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 7 | https://web.archive.org/web/20180129021150/https://www.metroll.com.au/home/index.php (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 8 | https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/1011/L107/semantics.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 9 | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vostok_1 (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 10 | https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/05/10/can-physics-and-philosophy-get-along/ (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 11 | https://web.archive.org/web/20160320015315/https://www.suretyaccountants.com.au/legal.php (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 12 | https://web.archive.org/web/20170624232440/https://aspenpitkin.com/Departments/Kids-First/Providers-/ (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 13 | https://kodefinance.com.au (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 14 | https://www.blueoregon.com/2007/05/this_is_my_city/#c370181 (accessed on 10 November 2024). |

| 15 | https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1949/12/8/excerpts-from-flanders-lectures-psenator-ralph/ (accessed on 10 November 2024). |