Metaphor and Metonymy in Food Idioms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

- Metaphor is primarily a cognitive mechanism.

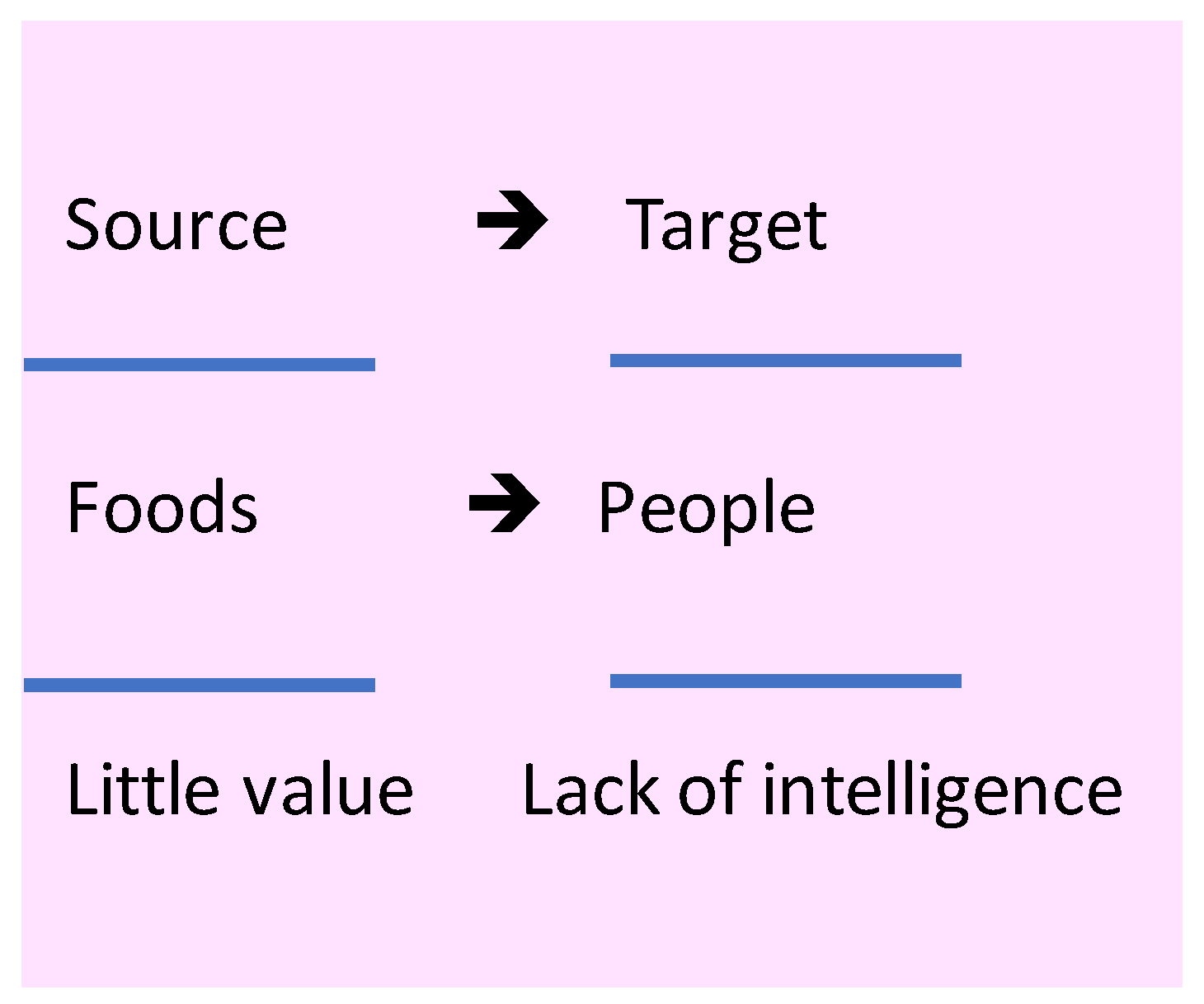

- Metaphor involves understanding a domain of experience (the target domain) in terms of a more concrete domain (the source domain).

- A metaphor is to be regarded as a mapping (e.g., a fixed set of conceptual correspondences) between a source domain and a target domain, where one or more features of the source are projected upon the target. As Lakoff (2006, p. 192) remarks, a metaphor is “an ontological mapping across conceptual domains,” so that “the essence of meaning is understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another” (Lakoff and Johnson 1980, p. 5).

- Any linguistic metaphor, or metaphoric expression, is an instantiation of a conceptual metaphor.

- (a)

- Source-in-target metonymies are those in which the source domain is a subdomain of the target domain, e.g., sign for state (‘to raise one’s eyebrows’). They involve domain expansion, which consists of broadening the amount of conceptual material associated with a domain.

- (b)

- Target-in-source metonymies are those in which the target is a subdomain of the source, for example part-for-part metonymies. They involve domain reduction and the consequent highlighting of part of a domain.

- Metonymic expansion of the metaphoric source or one of its correspondences, as in “to turn one’s back on somebody.” The action of turning one’s back in the metaphoric source domain is metonymically expanded onto a situation in which a person turns his back in order to ignore somebody.

- Metonymic reduction of the metaphoric source or one of its correspondences, as in “to have big ears.” The ears metonymically stand for good hearing (organ for sense).

- This element of the source domain is then projected upon a target domain in which a person eavesdrops.

- Metonymic expansion of a metaphoric target or one of its correspondences, as in “to clear one’s throat.” There is a metaphoric correspondence between clearing one’s throat and coughing. The result of this metaphoric mapping is then expanded by means of a metonymy, cough being understood as a sign to attract somebody’s attention.

- Metonymic reduction of the metaphoric target or one of its correspondences, as in “to open one’s eyes to something.” The person who opens his eyes describes metaphorically the person who becomes aware of something important. This metaphor relies on a metonymy, inasmuch as the open eyes represent the reality seen through a person’s eyes.

3. Methodology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barcelona, Antonio. 2000. Metaphor and Metonymy at the Crossroads. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Boers, Frank, and Seth Lindstromberg, eds. 2008. Cognitive Linguistic Approaches to Teaching Vocabulary and Phraseology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Buitrago, Alberto. 2012. Diccionario de dichos y frases hechas. Madrid: Espasa Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovol’skij, Dmitrij, and Elisabeth Piirainen. 2005. Figurative Language: Cross-Cultural and Cross-Linguistic Perspectives. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltan. 2002. Metaphor: A Practical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 2006. The contemporary theory of metaphor. In Cognitive Linguistics: Basic Readings. Edited by Dirk Geeraerts. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 186–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Turner. 1989. More Than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langlotz, Andreas. 2006. Idiomatic Creativity: A Cognitive-Linguistic Model of Idiom-Representation and Idiom-Variation in English. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Radden, Günter. 2000. How metonymic are metaphors? In Metaphor and Metonymy at the Crossroads. Edited by Antonio Barcelona. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz de Mendoza, Francisco José, and Olga Díez. 2002. Patterns of conceptual interaction. In Metaphor and Metonymy in Comparison and Contrast. Edited by Rene Dirven and Ralph Pörings. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 489–532. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz de Mendoza, Francisco José, and Alicia Galera. 2014. Cognitive Modeling. A Linguistic Perspective. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz de Mendoza, Francisco José, and José Luis Otal. 2002. Metonymy, Grammar and Communication. Granada: Comares. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz de Mendoza, Francisco José, and Lorena Pérez. 2011. The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor: Myths, Developments and Challenges. Metaphor and Symbol 26: 161–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefrig, Judit. 2004. Oxford Dictionary of Idioms. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Cocido is a dish made with chickpeas, meat and vegetables. |

| 2 | The dish consists of breadcrumbs fried with garlic and paprika. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Negro, I. Metaphor and Metonymy in Food Idioms. Languages 2019, 4, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030047

Negro I. Metaphor and Metonymy in Food Idioms. Languages. 2019; 4(3):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030047

Chicago/Turabian StyleNegro, Isabel. 2019. "Metaphor and Metonymy in Food Idioms" Languages 4, no. 3: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030047

APA StyleNegro, I. (2019). Metaphor and Metonymy in Food Idioms. Languages, 4(3), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030047