Coptic Language Learning and Social Media

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Social Media

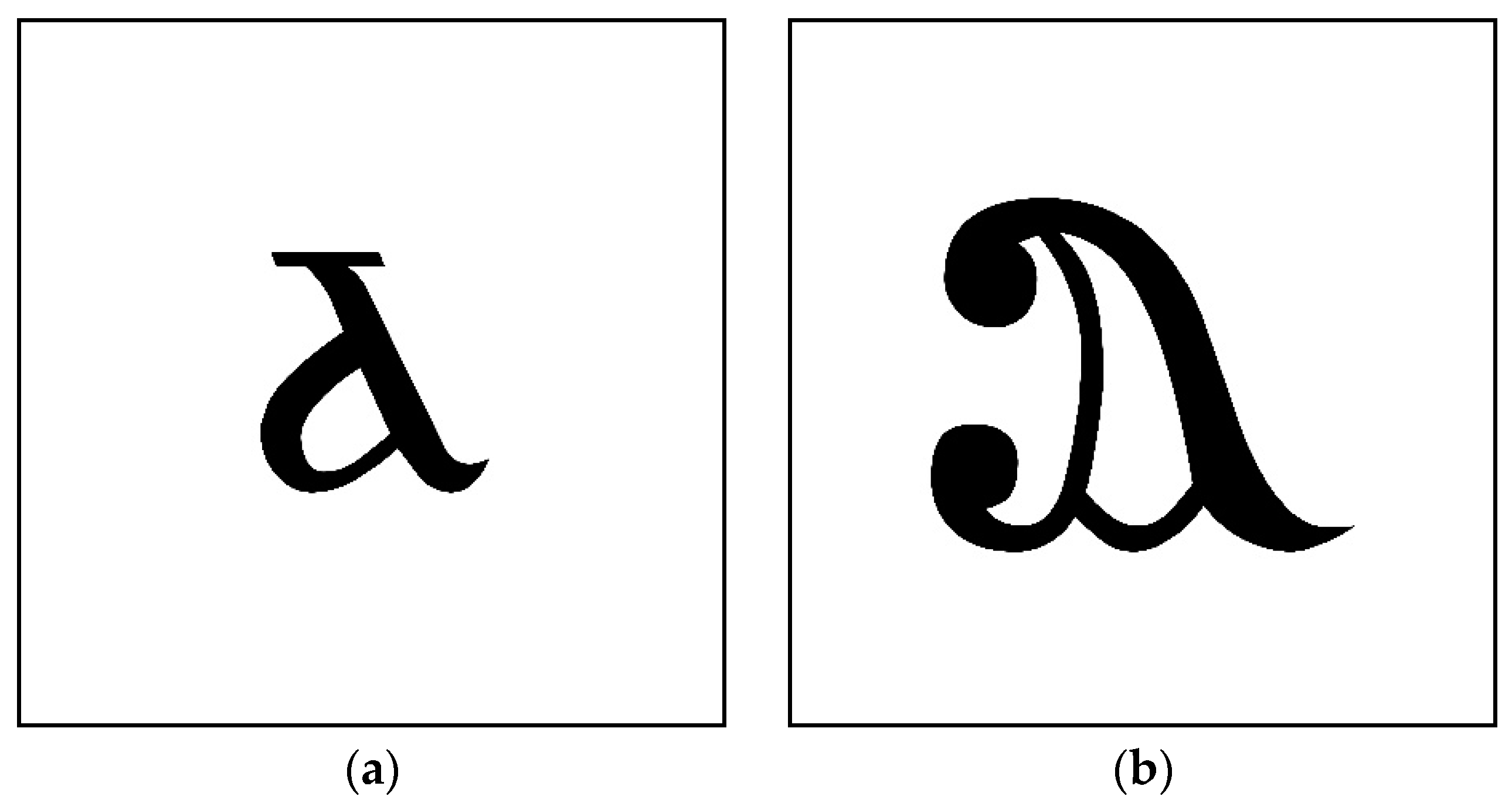

2.2. Coptic Language

2.3. Research Questions

- Who would use Coptic language learning material made available on the Internet?

- How would they describe their experience using the Coptic language learning material?

- How much exposure would the Coptic language learning material receive?

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Survey

4.1.1. Respondent Demographics

4.1.2. Respondent Language Background

4.1.3. Respondent Experience with the Coptic Language Learning Material

4.2. Web Analytics

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Question 1

5.2. Research Question 2

5.3. Research Question 3

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey

References

- Botros, Ghada. 2006. Religious identity as an historical narrative: Coptic Orthodox immigrant churches and the representation of history. Journal of Historical Sociology 19: 174–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenzinger, Matthias, Arienne M. Dwyer, Tjeerd de Graaf, Colette Grinevald, Michael Krauss, Osahito Miyaoka, Nicholas Ostler, Osamu Sakiyama, María E. Villalón, Akira Y. Yamamoto, and et al. 2003. Language vitality and endangerment. Paper presented at International Expert Meeting on UNESCO Programme Safeguarding of Endangered Languages, Paris, France, March 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cru, Josep. 2015. Language revitalisation from the ground up: promoting Yucatec Maya on Facebook. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 36: 284–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, David. 2014. Language Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781139923477. First published 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cunliffe, Daniel. 2007. Minority languages and the Internet: new threats, new opportunities. In Minority Language Media: Concepts, Critiques and Case Studies. Edited by Mike Cormack and Niamh Hourigan. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, ISBN 9781853599651. [Google Scholar]

- Duolingo. n.d. Language Courses for English Speakers. Available online: https://www.duolingo.com/courses (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2019. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 22nd ed. Dallas: SIL International, Available online: http://www.ethnologue.com/ (accessed on 3 March 2019).

- Foulin, Jean Noel. 2005. Why is letter-name knowledge such a good predictor of learning to read? Reading and Writing 18: 129–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, Philip B., and William H. Tunmer. 1986. Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education 7: 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, Robert M., Floyd J. Fowler Jr., Mick P. Couper, James M. Lepkowski, Eleanor Singer, and Roger Tourangeau. 2009. Survey Methodology. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., ISBN 9780470465462. [Google Scholar]

- Hermes, Mary, and Keiki Kawai’ae’a. 2014. Revitalizing indigenous languages through indigenous immersion education. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 2: 303–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, Mary, and Kendall A. King. 2013. Ojibwe language revitalization, multimedia technology, and family language learning. Language Learning & Technology 17: 125–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ishaq, Emile Maher. 1991. Coptic language, spoken. In Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz Suryal Atiya. New York: Macmillan, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Ann. 2015. Social media for informal minority language learning: exploring Welsh learners’ practices. Journal of Interactive Media in Education 2015: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Rhys James, Daniel Cunliffe, and Zoe R. Honeycutt. 2013. Twitter and the Welsh language. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 34: 653–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, Michael. 2007. Classification and terminology for degrees of language endangerment. In Language Diversity Endangered. Edited by Matthias Brenzinger. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 1–8. ISBN 9783110197129. [Google Scholar]

- Loprieno, Antonio, and Matthias Müller. 2012. Ancient Egyptian and Coptic. In The Afroasiatic Languages. Edited by Zygmunt Frajzyngier and Erin Shay. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 102–44. ISBN 9780521865333. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, Christopher. 2010. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, 3rd ed. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, Available online: http://www.unesco.org/culture/en/endangeredlanguages/atlas (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Ragheb, Nicholas. 2018. Coptic ethnoracial identity and liturgical language use. In Contemporary Christian Culture: Messages, Missions, and Dilemmas. Edited by Omotayo Banjo and Kesha Morant Williams. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 147–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ramzy, Carolyn M. 2013. Music: Performing Coptic expressive culture. In The Coptic Christian Heritage: History, Faith, and Culture. Edited by Lois M. Farag. New York: Routledge, pp. 160–76. ISBN 9781134666843. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, Saad Michael. 2010. The contemporary life of the Coptic Orthodox Church in the United States. Studies in World Christianity 16: 207–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, ISBN 9781473902480. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, Gary F., and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2018. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 21st ed. Dallas: SIL International, Available online: http://www.ethnologue.com/ (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Smith, Aaron, and Monica Anderson. 2018. Social Media Use in 2018. Washington: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, Bernard. 1995. Conditions for language revitalization: A comparison of the cases of Hebrew and Maori. Current Issues in Language and Society 2: 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Alissa Joy. 2017. How Facebook can revitalise local languages: lessons from Bali. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38: 788–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takla, Hany N. 2014. The Coptic language: The link to Ancient Egyptian. In The Coptic Christian Heritage: History, Faith, and Culture. Edited by Lois M. Farag. New York: Routledge, pp. 179–94. ISBN 9781134666843. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Sam L. No’eau. 2001. The movement to revitalize Hawaiian language and culture. In The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice. Edited by Leanne Hinton and Ken Hale. Leiden: Brill, pp. 133–44. ISBN 978900425449. [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook, Donald A., and Saad Michael Saad. 2017. Religious identity and borderless territoriality in the Coptic e-diaspora. Journal of International Migration and Integration 18: 341–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younan, Sameh. 2005. So, You Want to Learn Coptic? A Guide to Bohairic Grammar. Sydney: St. Mary, St. Bakhomious, and St. Shenouda Coptic Orthodox Church Kirawee. [Google Scholar]

| Theme | Responses |

|---|---|

| Challenging experience of teaching oneself | “Impossible! Books are too verbose and an impersonal way to learn a language so far from English/Arabic in structure” “I have only just started but the differences between Bohairic and Sahidic are annoying to decipher and there are not many resources dedicated to Coptic as a social language, more liturgical” “Difficult” “Frustrating to learn by yourself” |

| Strategies used to teach oneself | “I learnt the alphabet in a week and then practiced reading every day for a few months. Once a week I would ask one of the boys from church to let me read to them so they could fix my mistakes and help with pronunciation” “Just learning vocabulary by comparing translations during liturgy or other services” “I occasionally study it with a friend, brush up with a book, or occasionally attend a Coptic Orthodox Church but not regularly” “Learning Greek alphabet and reading Coptic icons” “My husband helped me learn to read it” “Mainly learning through reading the translation in the liturgy book” |

| Theme | Responses |

|---|---|

| Comprehension of and participation in worship | “I am interested in learning the Coptic language because it is the language of our fathers and so I may participate in the hymns of the church” “Understanding the liturgy more and being able to teach my child” “Understand church services better” |

| Ability to read ancient manuscripts | “At first it was to be able to sing Coptic hymns, now I think I would take it further to be able to read manuscripts” “For worship, and to explore further the ancient manuscripts and stories of desert fathers and mothers” “I am interested in ancient Coptic manuscripts and writings” |

| Preservation of the heritage and language | “To go back to my roots and preserve our heritage” “Heritage. While I believe that prayer should be easy to understand for all, I also don’t want our Coptic heritage to die” “Language revival of my ancestors” “To preserve the language of our forefathers” “The heritage of the Coptic people needs preservation” |

| Historical value of the language | “I am interested to learn more about an enduring and vibrant culture through language” “It has an interesting history” “Due to its historical and cultural value” |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deschene, D.N. Coptic Language Learning and Social Media. Languages 2019, 4, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030073

Deschene DN. Coptic Language Learning and Social Media. Languages. 2019; 4(3):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030073

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeschene, D. Nicole. 2019. "Coptic Language Learning and Social Media" Languages 4, no. 3: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030073

APA StyleDeschene, D. N. (2019). Coptic Language Learning and Social Media. Languages, 4(3), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030073