Emphasis Harmony in Arabic: A Critical Assessment of Feature-Geometric and Optimality-Theoretic Approaches

Abstract

:1. Introduction

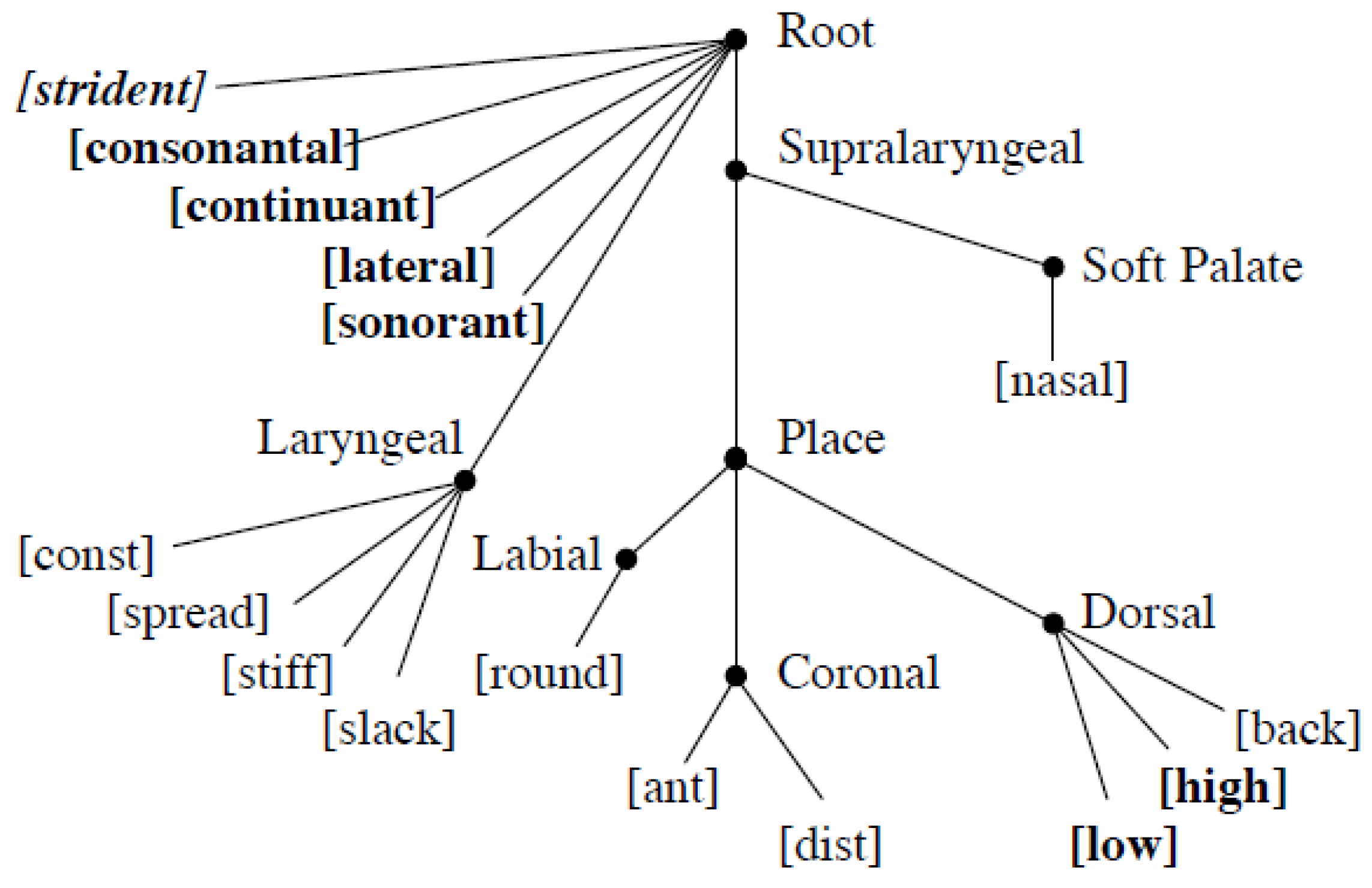

2. Feature-Geometric Analysis

2.1. Natural Classes as Functional Units

2.2. Guttural Segments and the [Pharyngeal] Feature

- 1-

- Active articulator. The gutturals are produced by three distinct gestures: a purely glottal one in the laryngeals, retraction of the tongue root and epiglottis and advancement of the posterior wall of the laryngopharynx in the pharyngeal, and a superior-posterior movement of the tongue dorsum in the uvulars.

- 2-

- Place of articulation. The gutturals are all produced in the posterior region of the vocal tract.

- 3-

- Spectrum. The gutturals all have relatively high F12. F1 is at the theoretical maximum in the case of laryngeals, close to the maximum for the pharyngeal, and higher than any orally articulated consonants in the case of uvulars.

- 4-

- Stricture. All gutturals except [ʔ] meet Catford’s (1977, p. 122) definition of approximant: “non-turbulent flow when voiced; but the flow becomes turbulent when they are voiceless”. Clements (1990) revises this definition to require oral stricture in non-approximants. With this modification, even [ʔ] is included in the class of approximants.

- (1)

- a. Plain roots: /malk/ [melek] ‘king/my king’, /sipr/ [se:per] ‘book’b. Medial guttural roots: /baʕl/ [baʕal] ‘master’, /lahb/ [lahab] ‘flame’

- (2)

- a. Plain roots: [jaʃrab] ‘he drinks’, [aʃrab] ‘I drink’b. Guttural roots: [jahardʒ] ‘he speaks’, [aHalam] ‘I dream’3

- (3)

- a. Plain roots: [dibbe:r] ‘he said’, [dalli:m] ‘weak ones’b. Guttural roots: [me:ʔe:n] ‘he refused’, [ra:ʕi:m] ‘evil ones’

- (4)

- a. [daradʒe] ‘step’, [kbi:re] ‘large’, [madrase] ‘school’b. [ʔəSSa] ‘story’, [ʕar:Da] ‘broad’, [xayya:Ta] ‘seamstress’

2.3. Guttural Segments and the [RTR] Feature

- (5)

- a. /ʔiq’t/ [ʔeq’t] ‘scraped off’b. /ʔuqweʔ/ [ʔoqweʔ] ‘drink’c. /məʕ’t/ [mʌʕ’t] ‘broken’d. /niʔhelus/ [niʔhelus] ‘good-natured’

- (6)

- /Dar/ [Dar] ‘he returned’, /Sif/ [Sef] ‘summer’, /Zur/ [Zor] ‘visit’

2.4. Counterarguments and the Exclusion of Emphatics

- (7)

- [ʔanʕamta] ‘those whom Thou hast favored’, [yanʔawana] ‘avoid’ 5, [yanHɪtun] ‘they used to hew out dwellings from the hills’ (Al-Solami 2013, p. 315)

- (8)

- [miŋ Tin] ‘an essence of clay’, [maŋDud] ‘clustered’, [miŋ qaraar] ‘possessing no stability’

- (9)

- [man ʔaːmana] ‘who believed’, [min haːd] ‘any guide’, [ʕaliːmun Hakiːm] ‘hearing and knowing’

- (10)

- /min qabl/ [mɪ̃ qabl] ‘before’, /man Suːra/ [mɑ̃ Suːra] ‘supported’, /kalimatan Tayyibah/ [kalimatɑ̃ Tayyibah] ‘good word’ (Altairi et al. 2017, p. 2)

- (11)

- /ʔal Sabr/ [ʔaS Sabr] ‘the patience’, /ʔal Tifl/ [ʔaT Tifl] ‘the child’, /ʔal Haq/ [ʔal Haq] ‘the truth’.

2.5. Strengths and Weaknesses of Feature Geometry

3. Optimality Theory

3.1. Directional Spreading and Blocking

3.1.1. Leftward Harmony

- (12)

- Leftward harmony: [ballaaS] ‘thief’, [HaDD] ‘luck’, [baaS] ‘bus’, [ʕaTʃaan] ‘thirsty’, [xayyaT] ‘tailor’8

- (13)

- RTR-LEFTAlign([RTR], Left, Word, Left)“Any instance of [RTR] is aligned initially in Word”9

- (14)

- Leftward harmony (McCarthy 1997, p. 235)

| /ballaaS/ | RTR-LEFT | IDENT-ATR |

| a. ☞ ballaaS | **** | |

| b. ballaaS | *!*** |

3.1.2. Rightward Harmony

- (15)

- (a) Rightward harmony: [SabaaH] ‘morning’, [ʔaTfaal] ‘children’, [Tuubak] ‘your blocks’, [Twaal] ‘long.pl’, [Sootak] ‘your voice’, [Seefak] ‘your sword’(b) Blocking of rightward harmony: [Tiinak] ‘your mud’, [Sayyaad] ‘hunter’, [ʕaTʃaan] ‘thirsty’, [Dajjaat] ‘type of voice.pl’

- (16)

- Rightward harmony (McCarthy 1997, p. 235)

| /SabaaH/ | RTR-RIGHT | IDENT-ATR |

| a. ☞ SabaaH | **** | |

| b. SabaaH | *!*** |

- (17)

- Rightward harmony and featural constraint RTR/HI&FR (McCarthy 1997, p. 236)

| /Sayyaad/ | RTR/HI&FR | RTR-RIGHT |

| a. ☞ Sayyaad | *** | |

| b. Sayyaad | *! |

- (18)

- RTR-LEFT >> RTR/HI&FR >> RTR-RIGHT >> IDENT-ATR

- (19)

- a. Local rightward harmony

- -

- To immediately following [a]: [Taaza] ‘fresh’, [SabaaH] ‘morning’, [Dalam] ‘he wronged’

- -

- To immediately following [Ca]: [ʔaDlam] ‘most unjust’, [Snaaf] ‘brands’

- -

- Blocked by following high segment: [ʕaTʃaan] ‘thirsty’, [Syaam] ‘fast’ and [SiHHa] ‘health’

b. Long-distance rightward harmony- -

- To following sequence of [a] and laryngeals [ʔ,h] or pharyngeals [ʕ,H]: [maSlaHa] ‘interest’, [SaHHaahaa] ‘he awakened her’, [Taʕnak] ‘your stabbing’

- -

- Blocked by following high segment: [SiHHa] ‘health’ and [Syaam] ‘fast’

- (20)

- IDENT-RTR, RTR-LEFT >> RTR/Hi >> RTR-To-a >> RTR/Lower-VT >> RTR-RIGHT >> IDENT-ATR

- (21)

- Local harmony and the spread to [a] (McCarthy 1997, p. 245)

| /SabaaH/ | IDENT-RTR | RTR-LEFT | RTR/Hi | RTR-To-a | RTR/Lower-VT | RTR-RIGHT | IDENT-ATR |

| a.☞ SabaaH | * | *** | * | ||||

| b. SabaaH | *! | * | **** | ||||

| c. SabaaH | **11! | * | *** | ||||

| d. sabaaH | *! |

- (22)

- Local harmony and the inclusion of a nasal (McCarthy 1997, p. 245)

| /Snaaf/ | IDENT-RTR | RTR-LEFT | RTR/Hi | RTR-To-a | RTR/Lower-VT | RTR-RIGHT | IDENT-ATR |

| a.☞ Snaaf | ** | * | ** | ||||

| b. Snaaf | *! | * | *** |

- (23)

- The effect of the high segment [ʃ] (McCarthy 1997, p. 246)

| /ʕaTʃaan/ | IDENT-RTR | RTR-LEFT | RTR/Hi | RTR-To-a | RTR/Lower-VT | RTR-RIGHT | IDENT-ATR |

| a.☞ ʕaTʃaan | * | * | *** | ** | |||

| b. ʕaTʃaan | *! | * | * | **** | |||

| c. ʕaTʃaan | *!* | * | * | *** |

consonant harmony processes are driven—or at the very least facilitated—by the relative similarity of the interacting segments; the more similar two cooccurring consonants are, the more likely it is that they will be forced to agree with one another in some particular feature.

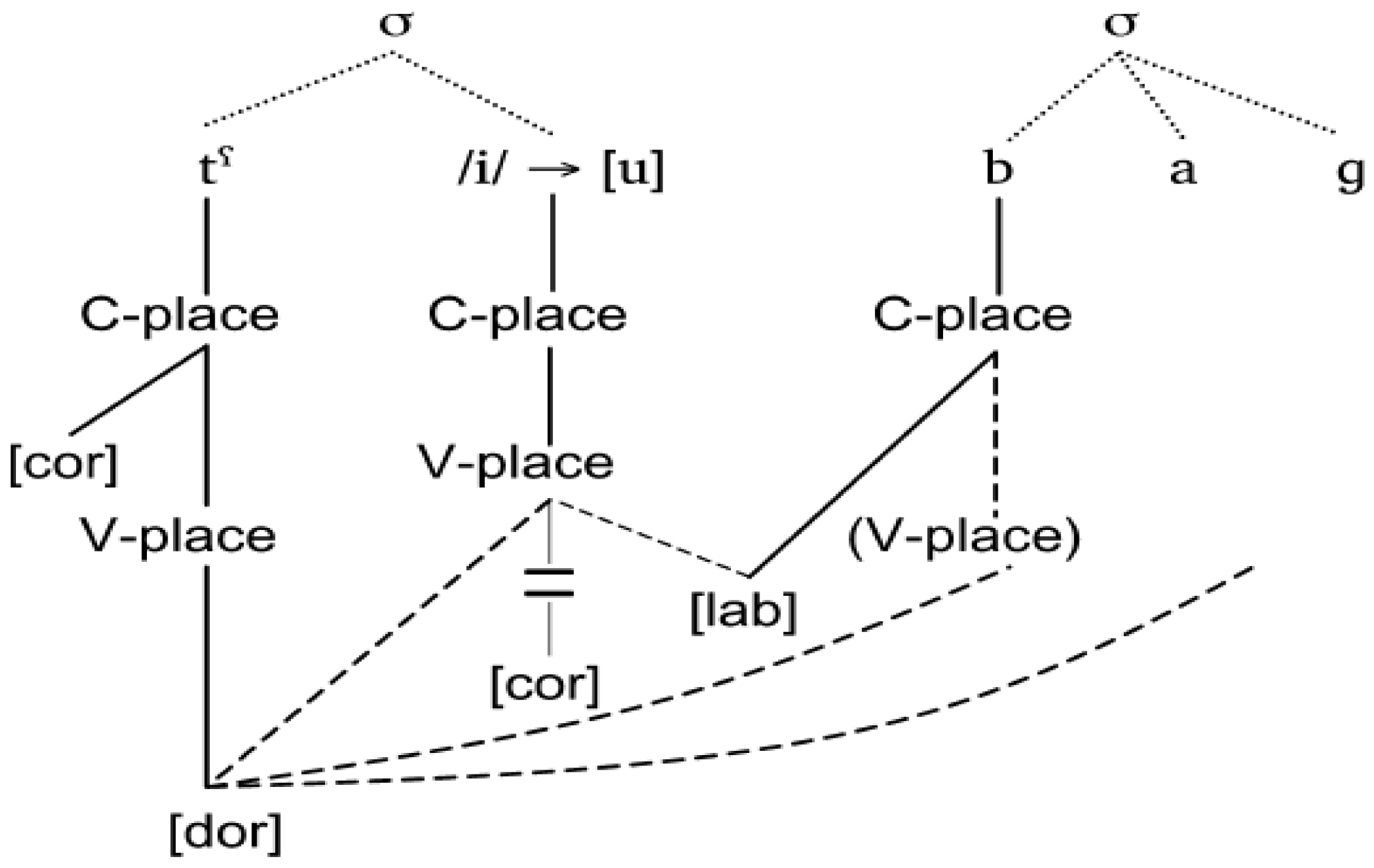

3.2. Labialization

- (24)

- Labial and back consonants as joint triggers of epenthetic [u]a. [nafux] ‘inflating’, [dabuɣ] ‘tanning’, [waquf] ‘religious endowment’, [Harub] ‘war’b. [ʕaTuf] ‘compassion’, [habuT] ‘dropping’, [TamuS] ‘bogging down’c. [Tabuʕ] ‘printing’, [Tabul] ‘drumming’, [Taʕum] ‘taste’, [Safun] ‘meditating’

- (25)

- Summary of labialization in CaCvC nouns (Youssef 2015, p. 76)

| C1 | C2 | V | C3 |

| Any | Labial | [u] | Back: emphatic or non-emphatic |

| Any | Back: emphatic or non-emphatic | [u] | Labial |

| Back: emphatic | Labial | [u] | Any |

| Back: emphatic | Any | [u] | Labial |

- (26)

- a. R/L-ALIGN[lab]V: Given an output sequence C[LAB](C)V/V(C)C[LAB], the right/left edge of [lab] must be aligned to the right/left edge of the sequence.b. R/L-ALIGN[dor]V: Given an output sequence C[DOR](C)V/V(C)C[DOR], the right/left edge of [dor] must be aligned to the right/left edge of the sequence.

- (27)

- Align V-[dor]STEM: The right/left edge of V-place[dor] must be aligned to the right/left edge of the stem word.

- (28)

- a. DEPLINK [lab]: An output association between a [lab] feature and a root node must have a corresponding association in the input.b. DEPLINK [dor]: An output association between a [dor] feature and a root node must have a corresponding association in the input.

- (29)

- the change from /Tabiʕ/ to [Tabuʕ]

| /Tabʕ/ | *COMPCODA | R/L-ALIGN [lab] V | Align V-[dor]STEM | DEP V-[cor] | DEPLINK [dor] | DEPLINK [lab] |

| a. Tabʕ | *! | * | ||||

| b. Tabiʕ | *! | * | * | |||

| c. ☞ Tabuʕ | **** | * |

3.3. Spread from Secondary Emphatic /r/

- (30)

- a. Leftward harmony: [infiga:r] ‘explosion’ [sifa:ra] ‘embassey’b. Rightward harmony: [ruma:di] ‘grey’ [ra:gil] ‘man’

- (31)

- a. [saar] ‘he went’, [xaddar] ‘he stupefied’, [akbar] ‘older’b. [saayir] ‘going’, [taxdiir] ‘stupefying’, [kabiir] ‘old’

- (32)

- a. [tigaara] ‘trade’, [ʔidaara] ‘administration’, [faʔr] ‘poverty’b. [tigaari] ‘trade adj.’, [ʔidaari] ‘administrative’, [faʔri] ‘poor adj.’15

- (33)

- a. [ʔasfor] ‘yellow’, [ʕaqrob] ‘scorpion’, [ʔitzakkor] ‘I remember’b. [ro:H] ‘he went’, [Diro:r] ‘proper name’, [ma:rimo:r] ‘proper name’

since labialization has the acoustic effect of lowering F1, while pharyngealization has the effect of raising F1, the fact that labialization is an enhancing feature, particularly in the oral emphatics, is further evidence that F2 lowering is more significant than F1 raising in the identification of emphasis.

4. Summary and Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Symbol | Description |

| H | Voiceless pharyngeal fricative |

| χ | Voiceless velar fricative |

| T | Voiceless dento-alveolar emphatic stop |

| D | Voiced inter-dental emphatic fricative |

| S | Voiceless dento-alveolar emphatic fricative |

| Z | Voiced dento-alveolar emphatic stop |

| ʕ | Voiced pharyngeal fricative |

| ʁ | Voiced velar fricative |

| q | Voiceless uvular stop |

References

- Al-Ani, Salman H. 1970. Arabic Phonology: An Acoustical and Physiological Investigation. The Hague: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Alghazo, Mohammad. 2013. Tongue Root Harmony in North Jordanian Arabic: An Optimal Domains Theory (ODT) Analysis. European Journal of Social Sciences 38: 344–51. [Google Scholar]

- Algryani, D. Ali. 2014. Emphasis Spread in Libyan Arabic. International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature 2: 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Masri, Mohammad, and Allard Jongman. 2004. Acoustic correlates of emphasis in Jordanian Arabic: Preliminary results. In Proceedings of the 2003 Texas Linguistics Society Conference. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Solami, Majed. 2013. Arabic Emphatics: Phonetic and Phonological Remarks. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 3: 314–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Solami, Majed Abdullah. 2017. Ultrasound Study of Emphatics, Uvulars, Pharyngeals and Laryngeals in Three Arabic Dialects. Canadian Acoustics 45: 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Altairi, Hamed, Jason Brown, Catherine Watson, and Bryan Gick. 2017. Tongue Retraction in Arabic: An Ultrasound Study. Proceedings of the Annual Meetings on Phonology 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Archangeli, Diana B., and Douglas George Pulleyblank. 1994. Grounded Phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Archangeli, Diana, and Douglas Pulleyblank. 1998. Grounded Phonology (Current Studies in Linguistics 25). Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, Peter, and Keren Rice. 1989. Segment structure and coronal underspecification. Phonology 6: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Muqbil, Musaed S. 2006. Phonetic and Phonological Aspects of Arabic Emphatics and Gutturals. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Wisconsin—Madison, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, Haim. 1964. Communal Dialects in Baghdad. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Catford, John Cunnison. 1977. Fundamental Problems in Phonetics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam, and Morris Halle. 1968. The Sound Pattern of English. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, George N. 1985. The Geometry of Phonological Features. Phonology Yearbook 2: 225–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, George N. 1990. The role of the sonority cycle in core syllabification. Papers in Laboratory Phonology 1: 283–333. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, George, and Elizabeth Hume. 1995. The internal organization of speech sounds. In The handbook of phonological theory. Edited by John A. Goldsmith. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 245–306. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Stuart. 1995. Emphasis Spread in Arabic and Grounded Phonology. Linguistic Inquiry 26: 465–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazeli, Salem. 1977. Back Consonants and Backing Coarticulation in Arabic. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1950. The Patterning of Root Morphemes in Semitic. WORD 6: 162–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Rania. 2012. Imala and rounding in a rural Syrian variety: Morphophonological and lexical conditioning. The Canadian Journal of Linguistics/La Revue Canadienne de Linguistique 57: 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halle, Morris, Bert Vaux, and Andrew Wolfe. 2000. On Feature Spreading and the Representation of Place of Articulation. Linguistic Inquiry 31: 387–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, Gunnar. 2001. Theoretical and Typological Issues in Consonant Harmony. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Herzallah, Rukayyah S. 1990. Aspects of Palestinian Arabic Phonology: A Non-Linear Approach. Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, Roman, C. Gunnar Fant, and Morris Halle. 1951. Preliminaries to Speech Analysis: The Distinctive Features and Their Correlates. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khedidja, Slimani, and Jisheng Zhang. 2017. Assimilation in the Djelfa Dialect of Algerian Arabic: An OT Account. Linguistics and Literature Studies 5: 213–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, Asher, and Thomas Baer. 1988. The Emphatic and Pharyngeal Sounds in Hebrew and in Arabic. Language & Speech 31: 181–205. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadin, Radwan S., and Yousef Bader. 1995. Emphasis assimilation spread in Arabic and feature geometry of emphatic consonants. Journal of Semitics 7: 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, John. 1994. The phonetics and phonology of Semitic pharyngeals. Phonological Structure and Phonetic Form: Papers in Laboratory Phonology 3: 191–233. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, John J. 1997. Process-Specific Constraints in Optimality Theory. Linguistic Inquiry 28: 231–51. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1995. Faithfulness and Reduplicative Identity. In Papers in Optimality Theory. Edited by Jill Beckman, Walsh Dickey and Suzanne Urbanczyk. Amherst: GLSA (Graduate Linguistic Student Association), Dept. of Linguistics, University of Massachusetts, pp. 250–384. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, Teresa Ann. 2009. The Phonology and Morphology of Filomeno Mata Totonac. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mielke, Jeff, and Elizabeth Hume. 2006. Distinctive Features. In Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, 2nd ed. Edited by Keith Brown. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 723–31. [Google Scholar]

- Moisik, Scott R., Ewa Czaykowska-Higgins, and John H. Esling. 2012. The epilaryngeal articulator: A new conceptual tool for understanding lingual-laryngeal contrasts. In Proceedings from Phonology in the 21st Century: In Honour of Glyne Piggott. Montreal: McGill University, vol. 22, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Morén, Bruce. 2003. The Parallel Structures Model of Feature Geometry. Working Papers of the Cornell Phonetics Laboratory 15: 194–270. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafawi, Eiman M. 2006. An Optimality Theoretic Approach to Variable Consonantal Alternations in Qatari Arabic. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Sharon. 1996. Variable Laryngeals and Vowel Lowering. Phonology 13: 73–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Sharon, and Rachel Walker. 2011. Harmony Systems. In The Handbook of Phonological Theory. Edited by John A. Goldsmith, Jason Riggle and Alan C. L. Yu. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 240–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sagey, Elizabeth. 1990. The Representation of Features in Non-Linear Phonology: The Articulator Node Hierarchy. New York: Garland. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, Kimary N. 2003. Postvelar Harmony. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Shosted, Ryan K., Maojing Fu, and Zainab Hermes. 2017. Arabic pharyngeal and emphatic consonants. In The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Linguistics. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sylak-Glassman, John C. 2014. Deriving Natural Classes: The Phonology and Typology of Post-Velar Consonants. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Vaux, Bert. 1996. The Status of ATR in Feature Geometry. Linguistic Inquiry 27: 175–82. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Janet. 2002. The Phonology and Morphology of Arabic. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, Islam. 2015. Vocalic labialization in Baghdadi Arabic: Representation and computation. Lingua 160: 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The [pharyngeal] feature distinguishes sounds articulated in “the area from the larynx and oropharynx inclusive” (McCarthy 1994, p. 198). (Rose 1996) argues that the pharyngeal sounds are divided into two subgroups according to the shape of the tongue root: the first subgroup include non-laryngeals sounds (i.e., uvulars, pharyngeals and emphatics) that have the [RTR] feature because they are articulated by constricting the pharynx or retracting the tongue root, and the second subgroup includes only laryngeals that have [ATR] feature since they are produced with tongue root advancement, rather than retraction (for an overview, see (Vaux 1996)). |

| 2 | Compared with F2 which ranges from 1200–1400 Hz, F1 is relatively high as it ranges from 900–1000 (McCarthy 1994, p. 196). |

| 3 | Based on the reviewer’s fieldwork, the forms [jahardʒ] ‘he speaks’ and [aHalam] ‘I dream’ have different pronunciations than the given ones. [jahardʒ] is produced as [jaharridʒ] or [jaharidʒ] with epenthesis, as indicated by McCarthy, but [aHalam] is articulated without the second [a] vowel as [aHlam], which may render the guttural in coda position since the epenthesis of [a] does not take place. Assuming the correctness of the reviewer’s observation, the avoidance of a guttural in coda position may not be a strong piece of evidence due to the existence of some exceptions. |

| 4 | It is not clear whether emphatics undergo the same processes like other gutturals. The only pieces of evidence for the inclusion of emphatics in the guttural class are imaala (raising/fronting) and emphasis spread (backing). |

| 5 | The correct pronunciation of ‘avoid’ is [yanʔawna], rather than [yanʔawana], as correctly pointed out by the reviewer. |

| 6 | As pointed out by the reviewer, the assimilation of lateral /l/ cannot be considered a strong piece of evidence since it occurs because emphatics are part of the “sun sounds” groups in Arabic but the assimilation of lateral /l/ does not occur with gutturals as they are part of the “moon sounds”. The assimilation of the lateral /l/ also occurs with other non-emphatic consonants as well such as /n, d, θ, ð/. |

| 7 | Lowering of the vowel does not take place in all verbs, as highlighted by the reviewer, verbs like [saʕal] [jasʕul] ‘cough’ [daxal] [jadxul] ‘enter’ do not involve lowering of the vowel. |

| 8 | Throughout the paper, the effects of emphasis harmony are assumed not to be allophonic in nature, rather, as a result of neutralising effects. The process of emphasis creates contrastive pairs which cannot be in complementary distribution, as can be seen in the contrast between [dɛm] ‘blood’ and [Dɛm] ‘he hugged’ (Al-Masri and Jongman 2004, p. 100, cited in Rose and Walker 2011, p. 247). |

| 9 | Although it is not argued in the paper whether the winner has a single RTR feature that is multiply-linked (as in feature geometric approaches) or multiple [RTR] features. I assume that the alignment constraints cause [RTR] feature to be multiply-linked (more details are in Section 3.3 below). |

| 10 | Regarding the fact that OT explains the phonology of any language by ranking of the set of universal constraints, OT seems more explanatory than FG. As a natural consequence of OT, a markedness constraint can be ranked higher than the constraint that motivates harmony in one direction but lower than the constraint that motivates harmony in another. Whereas FG approach may attempt to account for blocking segments in terms of their feature specifications, it is not clear how that can be explanatory for segments that block harmony in one direction but not the other. |

| 11 | |

| 12 | As highlighted by the reviewer, unlike pharyngealization which is a salient feature of all emphatic sounds, labialization is a feature that is involved in the production of some emphatics (i.e., [T] and [S]), but not others (i.e., [D] and [Z]). |

| 13 | Watson (2002, p. 269) indicates that labialization of the stem vowel in verbs occurs in other Arabic dialects when one of the root consonants is an oral emphatic. In Lebanese, for example, /rixiS/ ‘it became cheap’ becomes [ruxis], and in the Yemeni dialect of Baraddun /yigiSS/ ‘he cuts’ surfaces as [yiguSS]. |

| 14 | As pointed out by the reviewer, this phenomenon cannot be generalised to all Syrian dialects, and most probably to be restricted only to Oyoun Al-Wadi. |

| 15 | (Watson 2002, p. 275) mentions the form [dira:sa] ‘learning’ in which [r] is emphasised although it is adjacent to [i]. It is not clear whether this is a typo or not, therefore, the deemphasis of /r/ needs further research to be verified. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Bataineh, H. Emphasis Harmony in Arabic: A Critical Assessment of Feature-Geometric and Optimality-Theoretic Approaches. Languages 2019, 4, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040079

Al-Bataineh H. Emphasis Harmony in Arabic: A Critical Assessment of Feature-Geometric and Optimality-Theoretic Approaches. Languages. 2019; 4(4):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040079

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Bataineh, Hussein. 2019. "Emphasis Harmony in Arabic: A Critical Assessment of Feature-Geometric and Optimality-Theoretic Approaches" Languages 4, no. 4: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040079

APA StyleAl-Bataineh, H. (2019). Emphasis Harmony in Arabic: A Critical Assessment of Feature-Geometric and Optimality-Theoretic Approaches. Languages, 4(4), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040079