A Usage-Based Perspective on Spanish Variable Clitic Placement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| (1) | a. | Quiero | comprar = lo | (Enclisis) | |

| want-prs.1sg | buy-inf = it-acc-m3sg | ||||

| ‘I want to buy it’ | |||||

| b. | Lo | quiero | comprar | (Proclisis) | |

| it-acc-m3sg | want-prs.1sg buy-inf | ||||

| ‘I want to buy it’ | |||||

2. VCP and Grammaticalization

| (2) | Lo | compré. | ||||||

| it-acc-m3sg | buy-pst.1sg | |||||||

| ‘I bought it’ | ||||||||

| (3) | Para | comprar = lo | ||||||

| to | buy-inf = it-acc-m3sg | |||||||

| ‘To buy it’ | ||||||||

| (4) | a. | Quiero | comprar = lo | (Enclisis) | ||||

| want-prs.1sg | buy-inf = it-acc-m3sg | |||||||

| ‘I want to buy it’ | ||||||||

| b. | Lo | quiero | comprar | (Proclisis) | ||||

| it-acc-m3sg | want-prs.1sg | buy-inf | ||||||

| ‘I want to buy it’ | ||||||||

| (5) | a. | Lo[voy a conocer] mañana |

| ‘I [am going to meet] him tomorrow’ | ||

| b. | ??Lo [espero] [hacer] mañana. | |

| ‘I [hope] [to do] it tomorrow’ |

3. Variationist Study of VCP

3.1. Corpus and Data Extraction

3.2. Coding of Variable Constraints

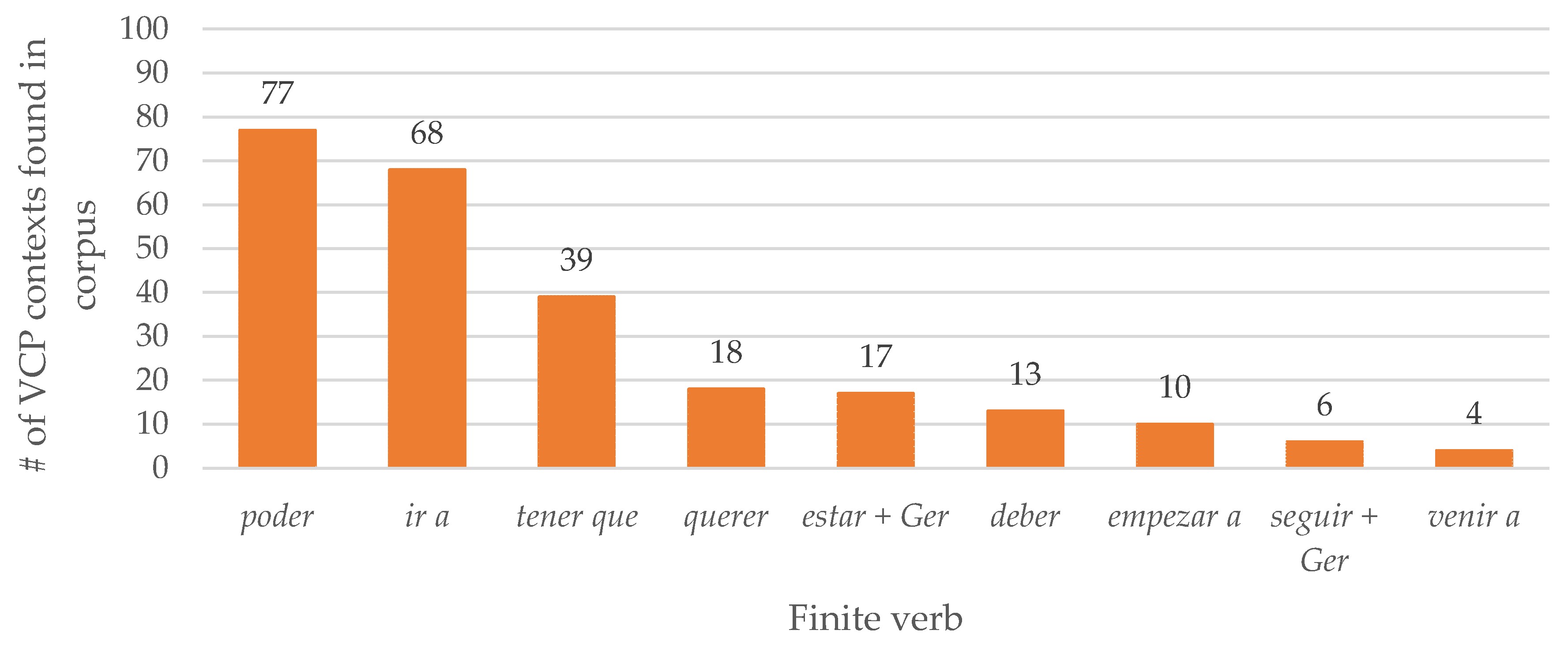

3.2.1. The Finite Verb

| (6) | Variable use with poder ‘can’: | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Proclisis: | |||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | únicamente | lo | puedo | hacer | en castellano (XXIV, 185:13)13 | ||||||||||||||||

| only | it-acc.m.sg | can-prs.1sg | do | in Spanish | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘I can only do it in Spanish’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Enclisis: | |||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | no | podés | hacer = lo | dando | vuelta | los esquís (IV, 73:3) | |||||||||||||||

| neg | can-prs.2sg | do = it-acc.m.sg | turn-ger | around | the skis | ||||||||||||||||

| ‘You cannot do it turning the skis around.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (7) | Variable use with ir (a) ‘go to’: | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Proclisis: | |||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | la | vamos | a | destruir (XXIV, 212:5) | |||||||||||||||||

| it-acc.f.sg | go-prs.1pl | to | destroy | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘We are going to destroy it’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Enclisis: | |||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | vamos | a | acortar = la | un | poquito (X, 160:3) | ||||||||||||||||

| go-prs.1pl | to | shorten = it-acc.f.sg | a | bit | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘We are going to shorten it a bit’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (8) | Variable use with tener que ‘have to’: | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Proclisis: | |||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | Lo | tengo | que | conversar | casualmente | (XXVI, 289:28) | |||||||||||||||

| it-acc.m.sg | have-prs.1sg | to | discuss | by the way | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘I have to discuss it, by the way’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Enclisis: | |||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | todo | eso | tengo | que | cuidar = lo | plenamente | (X, 160:3) | ||||||||||||||

| all | that | have-prs.1sg | to | take care of = it-acc.m.sg | completely | ||||||||||||||||

| ‘All that, I have to take care of [it] completely’ | |||||||||||||||||||||

3.2.2. Animacy of Clitic Referent

| (9) | Animate Referent: (lo ‘him’ = a man) | ||||||||||

| lo | iba | a | matar (XXII, p. 99, 10) | ||||||||

| it-acc.m.sg | go-pst.ipfv.3sg | to | kill | ||||||||

| ‘(he) was going to kill him’ | |||||||||||

| (10) | Inanimate Referent: (lo ‘it’ = a book) | ||||||||||

| Voy | a | mirar = lo. (XXIV, p. 166, 19) | |||||||||

| go-prs.1sg | to | look = it.acc.m.sg | |||||||||

| ‘I’m going to look at it’ | |||||||||||

| (11) | Propositional Referent: (lo ‘it’ = the fact that when a player has certain cards s/he should double the bet) | ||||||||||

| ahora | que | me | dijiste | lo | voy | ||||||

| now | that-rel | me-dat | tell-pst.prf.2sg | it-acc.m.sg | go-prs.1sg | ||||||

| a | tener | presente. (XXV, p. 225, 29) | |||||||||

| to | have | in mind | |||||||||

| ‘now that you told me, I will have it in mind’ | |||||||||||

3.2.3. Referent Accessibility

| (12) | Immediately Accessible Referent15: | |

| Bueno, lo llama- - - | y el lunes lo fui a ver. (XXIV, p. 202, 18) | |

| Translation: | ||

| Well, he calls him- - - and on Monday I went to see him-acc.3sg | ||

| (13) | Not Immediately Accessible Referent: | |

| Inf. A. ---Sí... esté... yo creo que sí. Yo he visto pasar por acá todos los colectivos [....] en la línea. | ||

| Inf. B. ---Bueno, pero [....] de la línea hasta que oscurezca. Después ya no va a haber más. | ||

| Inf. A. ---Pero después empiezan a retirar-los porque tienen miedo que pase alguna cosa. (XXVII, p. 319, 11–13) | ||

| Translation: | ||

| Inf. A. ---Yes… I believe that yes. I have seen all the buses [….] of the line go through here. | ||

| Inf. B. ---Well, but […] of the line until the evening. After that, there will be none. | ||

| Inf. A. ---But then they start removing them-acc.3pl because they are afraid that something might happen. | ||

3.2.4. Topic Persistence

| (14) | Persistent Referent: | |

| No, pero vos los podés preparar bien. Los podés preparar bien y los podés preparar mal. Yo los preparé mal. ¡Qué le vas a hacer! [risas] (XXI, p. 17, 12) | ||

| Translation: | ||

| No, but you can prepare them-acc.3pl well. You can prepare them well and you can | ||

| prepare them badly. I prepared them badly. What are you going to do! [laugh] | ||

| (15) | Not Persistent Referent: | |

| Inf. C. ---...un curso de la Cultura es Lingüística, que puedo dictar = lo sin preparar. | ||

| Inf. A. ---No, no, no; porque salís o... o porque... | ||

| Inf. B. ---Y porque tiene cursos [............] | ||

| Inf. C. ---Y el otro es drama que... que... que me interesa, me gusta y lo agarré, ¡qué voy a hacer!, que me exige cuatro o cinco horas de estudio por semana en casa, sábado y domingo. (XXI, p. 19, 19–22) | ||

| Translation: | ||

| Inf. C. ---...a class at the Cultura is Linguistics, which I can teach it-acc.3sg without preparing. | ||

| Inf. A. ---No, no, no; because you go out or… or because… | ||

| Inf. B. ---And because it has courses [………] | ||

| Inf. C. ---And the other one is Drama that… that… that interests me, I like it and I took it, what am I going to do!, it demands four or five study hours per week at home, on Saturday and Sunday. | ||

3.3. Multivariate Results

| (16) | El | “pues” | tenés | que | haber = lo | dicho | mucho (XXIV, p. 164, 24) |

| the | “so” | have-prs.2sg | to | have = it-acc.m.sg | said | a lot | |

| ‘You must have said “so” a lot’ | |||||||

3.4. Discussion of Corpus Study

- As in previous studies, clitic placement in this variety of Argentine Spanish is constrained by Referent Animacy Clitics since human referents tend to appear preverbally (proclisis).

- The nature of the finite verb construction emerged as the main factor conditioning clitic position. This result not only extends this known fact to a new dialect of Spanish, but it also provides evidence for the grammaticalization account that predicts a move away from enclisis for frequent periphrases where the finite verb has grammaticalized meaning. In the present study, we find this to be the case between more grammaticalized verbs that disfavor enclisis (e.g., ir a (future) and poder) as well as with more grammaticalized uses of a verb (e.g., ir a (future)) compared to more basic uses (e.g., ir a (movement) (see Schwenter and Torres Cacoullos 2014)).

- Tener que constitutes an intriguing case as a frequent grammaticalized verb that favors enclisis. This lack of one-to-one correspondence between grammaticalized verbs and VCP seems exceptional.

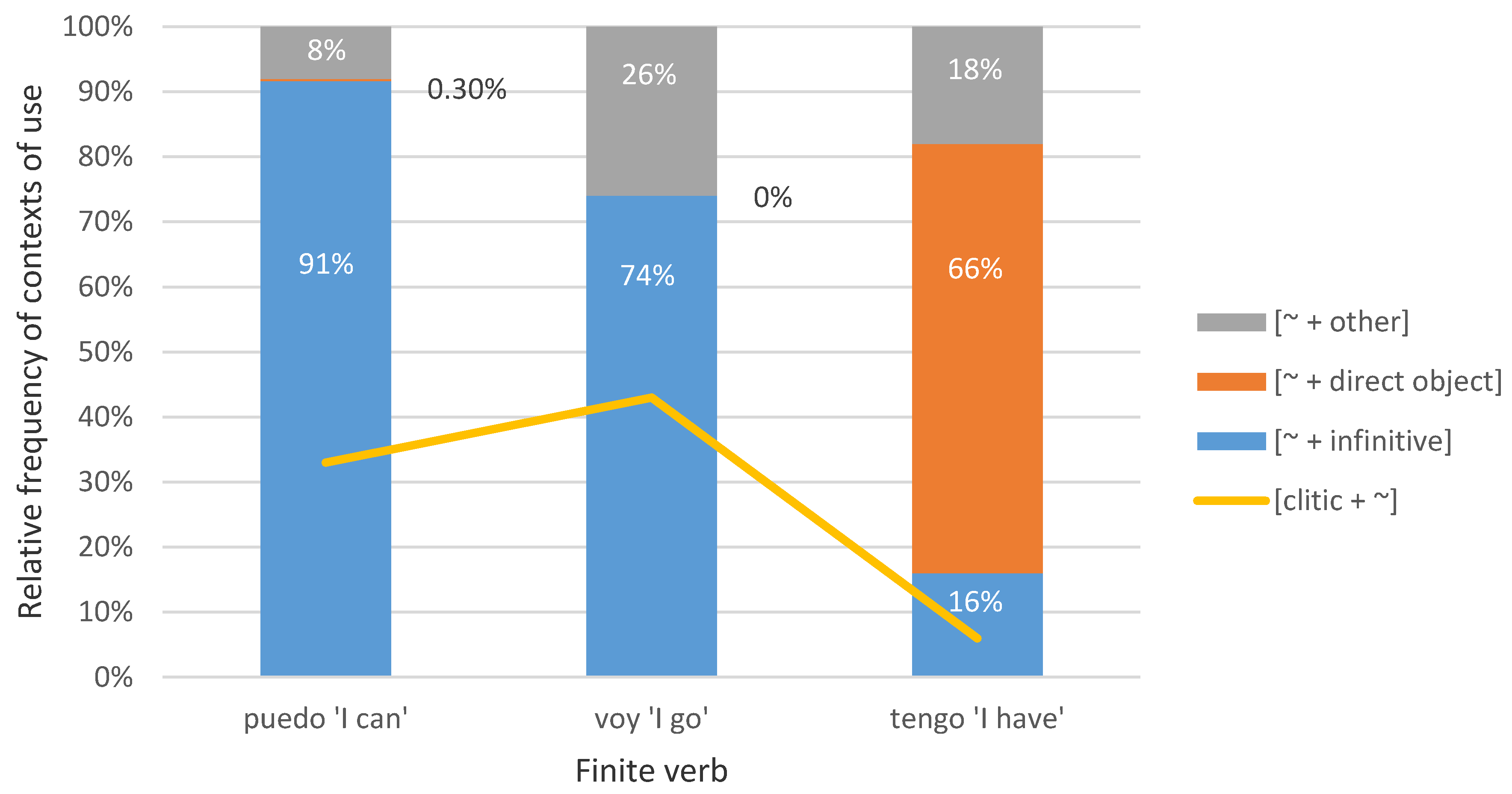

4. Motivating Construction Behavior

4.1. Unithood of [Tener Que + Infinitive]

| (17) | a. | No tengo que decir nada. | (Modal obligation periphrastic construction) |

| I don’t have to say anything. | |||

| b. | No tengo nada (que decir). | (Lexical construction) | |

| I don’t have anything (to say). | |||

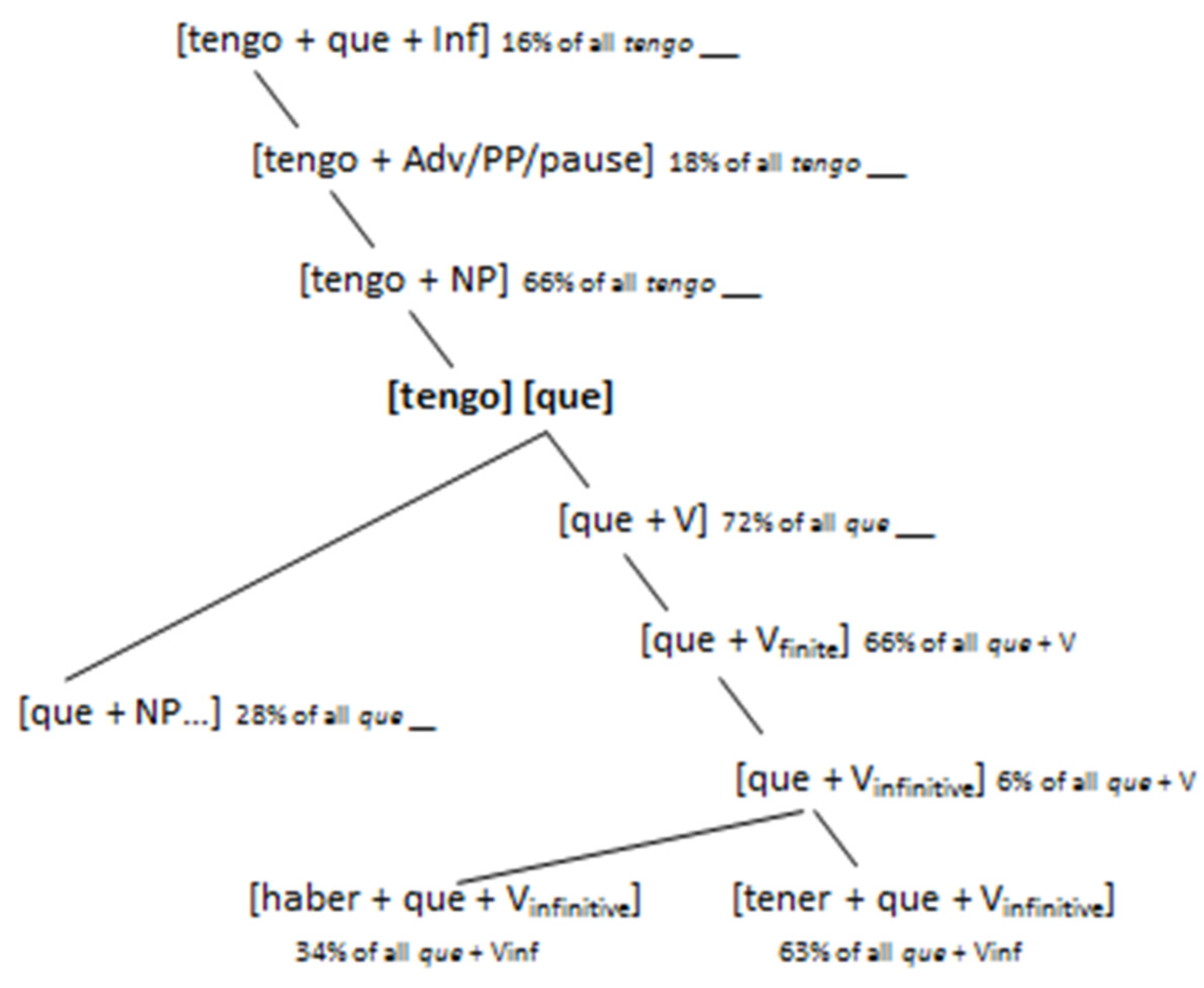

4.2. [Haber Que + Infinitive + Clitic] as an Analogical Model for [Tener Que + Infinitive]

| (18) | que + Infinitive | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Los | poetas tienen | que | escribir | lo | máximo | posible (CDE: 19-OR: Entrevista (ABC)) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| the | poets have-prs.3pl to | write | the | maximum possible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Poets have to write as much as possible’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (19) | que + (Adv) + V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sin embargo, | la | grabación | que | prefiero | en | la | actualidad | es | la | ||||||||||||||||||||

| however, | the | recording | that | prefer-prs.1sg | in | the | present | is | the | ||||||||||||||||||||

| “Misa en Si menor” | de | Bach (Entrevista (ABC) CDE: 19-OR) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| “Misa en Si menor” | by | Bach | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| “However, the recording that I prefer at present is the ‘…’ by Bach” | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (20) | que + NP/nominal clause/Adv/PP | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ¿Cuándo | descubrió | usted | que | el | piano | lo | era | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| when | discover-pst.pret.2sg | you | that | the | piano | it | be-pst.ipfv.3sg | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| todo | en | su | vida? (Entrevista (ABC) CDE: 19-OR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| everything | in | your | life | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘When did you discover that the piano was everything for you in life?’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (21) | tener + que + Infinitive | ||||||||||||||

| …sólo | tengo | que | tapar | las | cuatro | cuerdas | con | la | |||||||

| only | have-prs.1sg | to | cover | the | four | strings | with | the | |||||||

| mano. (Entrevista (ABC) CDE: 19-OR) | |||||||||||||||

| hand | |||||||||||||||

| ‘I only have to press the four strings with the hand’ | |||||||||||||||

| (22) | haber + que + Infinitive | ||||||||||||||

| hay | que | tener | paciencia (Entrevista (ABC) CDE: 19-OR) | ||||||||||||

| there be-prs.3sg | to | have | patience | ||||||||||||

| ‘one has to have patience’ | |||||||||||||||

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Exclusions as Part of Data Cleaning in Corpus Study

| (A1) | Me | lo | h-ic-e | de | un | color | sepia, | oscur-it-o, (XXVII, 325:20) |

| me-dat.1sg | it-acc.m.3sg | do-pret.1sg | of | a-m.sg | color | sepia, | dark-dim-m.sg, | |

| ‘I did it (for myself) on darkish sepia’ | ||||||||

| (A2) | esa | observación […] | me | la | han- | hecho | much-ísim-a-s (XXXI, 454:3) |

| that-f.s | observation […] | me-dat.1sg | it-acc.m.3sg | have-3pl | do-ptcp | many-sup-f-pl | |

| ‘many have made that observation to me’ | |||||||

| (A3) | en | una | mujer... esté... | es | más | fácil | entender-lo. (IX, 140:2) |

| in | a-f | woman… hm… | is | more | easy | understand-it-acc.m.3sg | |

| ‘It is easier to understand it in a woman’ | |||||||

| (A4) | Hay | que | hacer-lo | con | precisión (XIV, 223:1) |

| have-prs.3sg | to | do- it-acc.m.3sg | with | precision | |

| ‘One has to do it with precision’ | |||||

| (A5) | puede | adquirir | ese | cuadr-it-o- | y | tenerlo- | y | disfrutarlo (IX, 150:3) |

| can-3sg | purchase | that-m.sg | painting-dim-m | and | have-it-acc.m.3sg | and | enjoy-it-acc.m.3sg | |

| ‘can purchase that little painting and gave it, and enjoy it’ | ||||||||

| (A6) | porque | lo | tiene | que... (XXIX, 383:19) |

| Because | it-acc.m.3sg | have-3.sg | to… | |

| ‘because (s)he has to…’ | ||||

| (A7) | Méjico | va | a | tener-lo | mucho más | auténticamente | americano que | nosotros (XXX, 414:6) |

| Mexico | go-3.sg | to | have-it-acc.m.3sg | much more | authentically | American than | us | |

| ‘Mexico is going to have it more authentically American than us’ | ||||||||

| (A8) | no podemos... los trabajos ésos ahí en el Ides exponerlos en mitades. (XXI, 17:10) |

| we can’t…the Works those there at the Ides expose-them.acc.m.3pl in halves. |

| (A9) | a. | lo | tiene | que | haber | matado. (XXXI, 439:1)28 |

| it-acc-m3sg | has | to | have | killed | ||

| ‘he/she must have killed it’ | ||||||

| b. | lo | debo | haber | tenido | adentro | (XVI, 239:9) | |

| it-acc-m3sg | must | have | had | inside | |||

| I must have had it inside’ | |||||||

| c. | hay materias | que | uno | jamás | las va | volver | a | ver (I, 17:5) | ||

| exist subjects | that | one | never | them-acc-f3pl | go | to | return | to see | ||

| ‘there are subjects that one will never encounter again’ | ||||||||||

| d. | no | queríamos | seguirlo | viendo | todos | los | días | |

| neg | want.pret.1pl | keep = it-acc-m3sg | see.ger | all | the | days | ||

| ‘We didn’t want to keep seeing it every day.’ (XXII, 99:9) | ||||||||

ENCLISIS ONLY

- -

- All constructions consisting of a single non-finite form of a verb that, in present-day Spanish, can only take the clitic postverbally. This also includes imperatives (N = 165).

- -

- [gustar ‘like’ + Infinitive-Clitic] constructions (N = 9)(A10) me gustaría hacerlo (XXIV, 210:9)

- -

- [tratar de ‘try to’ + Infinitive-Clitic] constructions (N = 6)(A11) El trata de solucionarlos en lo más posible (V, 93:1)

- -

- Expressions with [vale la pena/da pena ‘it’s a pity’+ Infinitive] (N = 2)(A12) A mí me da mucha pena- - - dejarlo, abandonarlo (XXIX, 387:17)

- -

- [dejar de ‘stop’ + Infinitive-Clitic] constructions (N = 2)(A13) así dejás de--- llamarlo. (XXIV, 203:11)

- -

- [entrar a ‘begin’ + Infinitive-Clitic] constructions (N = 2)(A14) entraría a respetarla (X, 157:1)

- -

- [andar ‘go’+ Gerund-Clitic] (N = 2)(A15) Pero vos sabés que yo ando persiguiéndolo a este señor (XIV, 203:2)

- -

- Constructions occurring only once in the corpus with enclisis: [estar ‘be’ + PP + PP-Clitic] (A15),[haber ‘there be’ + NP + PP-Clitic] (A16), [quedar en ‘agree to’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A17), as well as [acordarse ‘remember’ + haber ‘having’+ Participle-Clitic] (A18), [animarse a ‘fancy’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A19), [atreverse a ‘dare’ + infinitive-Clitic] (A20), [comprometerse a ‘commit to’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A21), [convenir ‘arrange/agree’+ Infinitive-Clitic] (A22), [intentar ‘attempt’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A23), [lograr ‘achieve’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A24), [molestar ‘bother’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A25), [negarse a ‘refuse’ + infinitive-Clitic] (A26), [pensar ‘consider’ + infinitive-Clitic] (A27), [ponerse a ‘start’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A28), [proponerse ‘intend’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A29), [pretender ‘pretend’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A30), and [terinar por ‘end’ + Infinitive-Clitic] (A31).(A16) no estoy en edad de hacerlo tampoco (XIV, 216:5)(A17) no hay forma de aprenderlo (XXII, 88:11)(A18) Quedé en irla a visitar el miércoles. (XXXII, 474:7)(A19) Desde chico me acuerdo haberlo visto (XXVII, 323:3)(A20) ¿Te animás a escucharlo de nuevo? (IV, 69:1)(A21) Es que uno no se atreve a dejarlos a ver qué pasa. (IX, 154:7)(A22) Cada cual se comprometió en su país a seguirlos trabajando... (XXI, 17:20)(A23) si ese juicio me conviene conciliarlo o no (XXIII, 114:3)(A24) intentar criarlo allí (VIII, 128:5)(A25) no logro localizarlo (XXIV, 203:2)(A26) nos molestaba hacerla (VII, 114:3)(A27) se negaba a ponerlos en la mesa (IV, 82:9)(A28) así que piensa emplearlo en un... Un empleo comercial nomás. (V, 88:2)(A29) un día me pongo a hacerla (V, 93:7)(A30) me propuse- - - hacerlo hasta--- un momento determinado... (XXI, 57:19)(A31) como él pretendió hacerlo ver (XXIV, 140:6)(A32) a fuerza de escucharlas terminarán por corearlas junto a nosotros (XIX, 285:1)

PROCLISIS ONLY

- -

- All cases of a clitic used with a single finite verb were excluded, as they only allow the clitic to appear preverbally (N = 1265).

- -

- [Clitic + hacer ‘make’ + Infinitive] constructions (to make someone do something) (N = 12)(A33) El lo hizo correr (XXVIII, 371:12)

- -

- [Clitic + ir ‘go’ + Gerund] constructions (N = 11)(A34) Yo las fui guiando (XI, 169:11)

- -

- [Clitic + llegar a ‘get to’ + Infinitive] (N = 6)(A35) un poco lo llego a dominar y me aburre después (I, 24:18)

- -

- [Clitic + dejar ‘stop’ + Infinitive] (N = 4)(A36) Te está diciendo que lo dejes pensar

- -

- [Clitic + volver a ‘do…again’ + Infinitive] (N = 3)(A37) la he vuelto a hacer (XXIV, 212:5)

- -

- [Clitic + haber ‘there be’ de + Infinitive] constructions (N = 2)(A38) No la ha de saber manejar (XXII, 102:4)

- -

- [Clitic + ver ‘see’ + Infinitive] (N = 2)(A39) los veo manejarse en coche (XXIII, 131:11)

- -

- [Clitic + deber de ‘must’ + haber ‘have’+ Participle] constructions (N = 2)(A40) Pero él la debe de haber presentido a traves de las sombras (XXIX, 396:1)

- -

- [Clitic + invitar a ‘invite to’+ Infinitive] (N = 2)(A41) de tanto en tanto la invite a salir (X, 158:1)

- -

- Constructions occurring only once in the corpus with proclisis: [Clitic + dar a entender ‘suggest’] (A41), [Clitic + obligar a ‘force to’ + Infinitive] (A42), [Clitic + mandar (a) ‘have something done’ +Infinitive] (A43), [Clitic + saber ‘know’ + Infinitive] (A44), and [Clitic + terminar de ‘finish’ + Infinitive] (A45).(A42) como lo dan a entender sus títulos (XX, 294:1)(A43) Por eso, los obligó a leer. (XI, 177:12)(A44) No los mandé hacer todavía. (XXIV, 144:7)(A45) no lo sé hacer (XXIV, 158:5)(A46) Todavía no lo terminamos de- - - elaborar (XIV, 213:3)

References

- Aijón Oliva, Miguel A. 2011. Variación Sintáctica y creación de estilos: Los clíticos reflexivos en el discurso. In Variación Variable. España: Círculo Rojo, pp. 21–56. [Google Scholar]

- Aijón Oliva, Miguel A., and Julio Borrego Nieto. 2013. La variación gramatical como forma y significado: El uso de los clíticos verbales en el español peninsular. Lingüística 29: 93–126. [Google Scholar]

- Aissen, Judith L., and David M. Perlmutter. 1976. Clause Reduction in Spanish. In Studies in Relational Grammar 1. Edited by David M. Perlmutter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 360–404. [Google Scholar]

- Barrenechea, Ana M., ed. 1987. El habla culta de la ciudad de Buenos Aires: Materiales Para su Estudio. Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional de Buenos Aires. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Joseph R. 2013. Grammaticalization and Variation in the Modal Domain of Obligation: The Evolution of Spanish [tener que + Infinitive]. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Blas Arroyo, José L. 2018. Comparative variationism for the study of language change: Five centuries of competition amongst Spanish deontic periphrases. Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics 4: 177–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blas Arroyo, José L., and Kim Schulte. 2017. Competing modal periphrases in Spanish between the 16th and the 18th centuries. Diachronica 34: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, Esther L., and Javier Rivas. 2012. Grammatical relation probability: How usage patterns shape analogy. Language Variation and Change 24: 317–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan. 1985. Morphology: A Study of the Relation between Meaning and Form. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 1988. Morphology as lexical organization. In Theoretical Morphology. Edited by Michael Hammond and Michael Noonan. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 1998. The emergent lexicon. Chicago Linguistic Society 34: 421–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2001. Phonology and language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2003. Mechanisms of change in grammaticization: The role of frequency. In The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Edited by Brian D. Joseph and Richard Janda. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 602–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2010. Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan L., and William Pagliuca. 1987. The evolution of future meaning. In Papers from the 7th International Conference on Historical Linguistics. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 109–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan, and Sandra A. Thompson. 1997. Three frequency effects in syntax. Berkeley Linguistics Society 23: 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 2006. Restructuring and Functional Heads. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Mark. 1995. Analyzing Syntactic Variation with Computer-Based Corpora: The Case of Modern Spanish Clitic Climbing. Hispania 78: 370–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Mark. 1998. The evolution of Spanish clitic climbing: A corpus-based approach. Studia Neophilologica 69: 251–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Mark. 2002. Corpus del Español: 100 Million Words, 1200s–1900s. Available online: http://www.corpusdelespanol.org (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- DuBois, John W. 1985. Competing motivations. In Iconicity in Syntax. Edited by John Haiman. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 343–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Ulloa, Teresa. 2001. Perífrasis verbales en el castellano de Bermeo (Bizkaia). Revista Española de Lingüística/Spanish Journal of Linguistics 30: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Garachana, Mar. 2017. Perífrasis formadas en torno a tener en español. Ser tenudo/tenido o/a/de + infinitivo, tener a/de + infinitivo, tener que + infinitivo. In La Gramática en la Diacronía. La Evolución de las Perífrasis Verbales Modales en Español. Edited by Mar Garachana. Madrid-Frankfurt: Iberoamericana/Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Garachana, Mar, and Áxel Hernández. 2017. La reestructuración del sistema perifrástico en el español decimonónico. El caso de haber de/tener de + infinitivo, haber que/tener que + infinitivo. In Herencia e Innovación en el Español del Siglo XIX. Edited by Elena Carpi and Rosa M. García Jiménez. Pisa: Pisa University Press, pp. 127–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, Brigit. 2002. Clitics between Syntax and Lexicon. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, vol. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Giammatteo, Graciela M., and Ana M. Marcovecchio. 2009. Perífrasis verbales: Una mirada desde los universales lingüísticos. Sintagma 21: 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Givón, Talmy. 1971. On the verbal origin of the Bantu verb suffixes. Studies in African linguistics 2: 145. [Google Scholar]

- Givón, Talmy. 1979. On Understanding Grammar. New York: Academics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Givón, Talmy. 1983. Topic continuity in discourse: An introduction. In Topic Continuity in Discourse: A Quantitative Cross-Language Study. Edited by Talmy Givón. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 3, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Givón, Talmy. 1992. The grammar of referential coherence as mental processing instructions. Linguistics 30: 5–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givón, Talmy. 1995. Coherence in text vs. coherence in mind. In Coherence in Spontaneous Text. Edited by M. A. Gernsbacher and T. Givón. Pittsburgh: John Benjamins, pp. 59–115. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Adele E. 1995. Construction Grammar. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Adele E. 2006. Constructions at Work: The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Manzano, Pilar. 1992. Perífrasis Verbales Con Infinitivo: Valores y usos en la Lengua Hablada. Madrid: UNED. [Google Scholar]

- González López, Verónica. 2008. Spanish Clitic Climbing. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- González López, Verónica. 2013. Asturian identity reflected in pronoun use: Enclisis and proclisis patterns in Asturian Spanish. In Selected Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho and Sara Beaudrie. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmestad, Aarnes. 2006. Clitic climbing in Caracas Spanish: A sociolinguistic study of ir and querer. Indiana University Linguistics Club Working Papers 6: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, Bernd, and Tania Kuteva. 2002. World Lexicon of Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, Bernd, and Mechthild Reh. 1984. Grammaticalization and Reanalysis in African Languages. Hamburg: Helmet Buske. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul J. 1987. Emergent Grammar. Berkeley Linguistics Society 13: 139–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, Paul J., and Elizabeth C. Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Daniel E. 2009. Getting off the GoldVarb standard: Introducing Rbrul for mixed-effects variable rule analysis. Language and Linguistics Compass 3: 359–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar: Descriptive Application. Stanford: Stanford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, David. 1970. General semantics. Synthese 22: 18–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, David. 1979. Scorekeeping in a Language Game. Journal of Philosophical Logic 8: 339–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Díaz, Eva. 2003. La frecuencia de haber y tener en las estructuras perifrásticas de obligación. Algún fenómeno de variación en el español de Cataluña. Interlingüística 14: 691–94. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, Peter H. 2007. Animacy Hierarchy. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Linguistics. Available online: https://www-oxfordreference-com.libweb.lib.utsa.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199202720.001.0001/acref-9780199202720-e-173?rskey=reZLMy&result=1 (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- Miller, D. Gary, and Elly van Gelderen. 2017. Grammaticalization. In Oxford Bibliographies Online: Linguistics. Available online: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199772810/obo-9780199772810-0019.xml (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Myhill, John. 1988. The Grammaticalization of Auxiliaries: Spanish Clitic Climbing. Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 14: 352–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myhill, John. 1989. Variation in Spanish clitic climbing. In Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1988. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 227–50. [Google Scholar]

- Myhill, John. 2005. Quantitative methods of discourse analysis. In Quantitative Linguistics: An International Handbook. Edited by Reinhard Köhler, Gabriel Altmann and Rajmund Piotrowski. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 471–98. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli, Donna. J. 1981. Semantic Interpretation vs. Lexical Governance: Clitic Climbing in Italian. Language 57: 841–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbertz, Hella. 1998. Verbal Periphrases in a Functional Grammar of Spanish. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2014. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.r-project.org (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- Requena, Pablo E. 2015. Direct Object Clitic Placement Preferences in Argentine Child Spanish. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1976. Ristrutturazione. Rivista Di Grammatica Generativa Roma 1: 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1978. A restructuring rule in Italian syntax. Recent transformational studies in European languages. In Linguistic Inquiry Monograph. Edited by Samuel J. Keyser. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 3, pp. 113–58. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, B. 1905. On Denoting. Mind, New Series 14: 479–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenter, Scott A., and Rena Torres Cacoullos. 2014. Competing constraints on the variable placement of direct object clitics in Mexico City Spanish. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics 27: 514–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1994. Language Contact and Change: Spanish in Los Angeles. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott, Sarah, and Ella Smith. 2007. ¿Subir o no subir? A Look at Clitic Climbing in Spanish. Paper presented at the 36th New Ways of Analyzing Variation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, October 12. [Google Scholar]

- Strozer, Judith R. 1976. Clitics in Spanish. Ph.D. Dissertation, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Suñer, Margarita. 1980. Clitic Promotion in Spanish Revisited. In Contemporary Studies in Romance Languages. Edited by Frank H. Naussel. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club, pp. 300–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali A. 2006. Analysing Sociolinguistic Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Cacoullos, Rena. 1999. Construction frequency and reductive change: Diachronic and register variation in Spanish clitic climbing. Language Variation and Change 11: 143–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Troya Déniz, Magnolia, and Ana M. Pérez Martín. 2011. Distribución de clíticos con perífrasis verbales en hablantes universitarios de las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Lingüística 26: 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich, Uriel. 1966. On the semantic structure of language. In Universals of Language, 2nd ed. Report of a Conference Held at Dobbs Ferry, NY, USA, April 13–15. Edited by Joseph H. Greenberg. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 114–71. First published 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Zabalegui, Nerea. 2008. La posición de los pronombres átonos con verbos no conjugados en el español actual de Caracas. Akademos 10: 83–107. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | In this study, I will also use “strength of association” to refer to “degree of unithood”. |

| 3 | With imperatives, they occur before negative imperatives (No lo toques ‘Do not touch it’), but after affirmative imperatives (Tocalo ‘Touch it’). I do not consider such a context to be a variable context similar to (1a) and (1b). |

| 4 | I will use constructions and periphrases to refer to [finite verb+non-finite verb] units here, but I acknowledge that within formal linguistics, only some of these sequences pass certain tests to show their consolidation as periphrases. |

| 5 | For other languages (or dialects) in which CC seems obligatory, see (Cinque 2006, p. 32, fn. 47). |

| 6 | The authors operationalize high frequency based on observed distribution. This results in verb types that account for >8% of all the extracted tokens in the corpora being considered to be frequent. Under this assumption, tener que ‘have to’ is among the most frequent verbs. |

| 7 | Each of these verbs accounted for at least 3% (a minimum of 318 tokens) of all the tokens found in the spoken data (N = 10,626). |

| 8 | “A proposed hierarchical ordering of noun phrases etc. ranging from personal pronouns, such as I, as maximally ‘animate’ to forms referring to lifeless objects as minimally ‘animate’…” (Matthews 2007). |

| 9 | |

| 10 | With the exception of Déniz (2003) in Troya Déniz and Pérez Martín (2011, p. 15), who examined over twelve dialects included in the Macrocorpus de la norma lingüistica de las principales ciudades del mundo hispánico reporting 74% proclisis. |

| 11 | Even though this is quite a small data set, the results of this study replicate some previous findings with larger corpora and add to the description of this phenomenon in different dialects, which could be used to establish comparisons across varieties of Spanish, as mentioned by (Gudmestad 2006, pp. 13–14). In addition, in the current manuscript, the corpus study mainly serves the purposes of (a) replicating the effects of the main constraints on VCP in a dialect for which no variationist study has examined this phenomenon, and (b) illustrating the exceptional behavior of tener que ‘have to’ to motivate the theoretical analysis. While a larger dataset would be required for a study that offers proof of a novel effects or where the corpus study is the main focus, I think that the small-scale study contributes to the purposes of the present study (“a” and “b” above). |

| 12 | Formal approaches have also noted how clitic climbing (CC) is possible with some types of verbs. Verbs have, for example, been classified into those that trigger structure simplification and those that do not. Structure simplification would then make the finite and non-finite elements of these periphrases belong to the same clause, thus allowing preverbal clitics. Aissen and Perlmutter (1976) identify “trigger” verbs (such as querer ‘want’, tratar ‘try’, and soler ‘be in the habit of’) and “non-trigger” verbs (like insistir ‘insist’, soñar ‘dream’, and parecer ‘seem’). The authors support the Clause Union hypothesis (rendering structure simplification) and discard the existence of a specific rule that would account for preverbal clitics. Rizzi (1976), on the other hand, relates proclisis to the verb by proposing a lexically governed rule called ‘Restructuring’, which allows clitics to appear preverbally. Both Rizzi (for Italian) and Suñer (1980) (for Spanish) agree that modals, aspectuals, and motion verbs allow proclisis in addition to enclisis. |

| 13 | Examples from the corpus are followed by references to the source in the format: sample number (in Roman numerals), page number:line number. |

| 14 | I also coded for the syntactic function of cases of immediate mention, such as Subject, Object, and Other. This was not significant, so the final analysis collapsed all syntactic functions. |

| 15 | The translations corresponding to the examples for each of the discourse factors are provided immediately after the Spanish in more idiomatic form only. |

| 16 | Unlike Schwenter and Torres Cacoullos (2014), here, I included interlocutor tokens as well as quotative and other discourse formulas. |

| 17 | Two finite verbs (seguir and venir) did not reach a minimum of 10 tokens each and were initially collapsed into an “Other” category. This, however, resulted in an interaction between finite verb and animacy that not only lacked theoretical motivation in the present study, but also worsened the model fit as measured by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). So, we removed the “Other” category from the final model. |

| 18 | In Davies (1995), the only dialect that included data from popular (lower socioeconomic status) speakers showed the lowest overall rate of enclisis compared to all the other dialects in that study, for which data came from Habla Culta corpora, which contain interviews with educated speakers only. Similarly, Schwenter and Torres Cacoullos (2014) showed lower rates of enclisis in Mexican corpora of Habla Popular as well as youth speech than in Habla Culta (educated speech). |

| 19 | I selected 1sg forms because they are the second most frequent singular forms after 3SG. For example, in the oral Corpus del Español (Genre/Historical) the frequencies are: va ‘he/she/it goes’, N = 7096; voy ‘I go’, N = 2661; and vas ‘you go’, N = 862. The advantage of 1SG over 3SG is that the subject is constant and known in the former. With the latter, the subjects can vary in animacy, specificity, and can even be propositional. So, for simplicity, I selected 1SG forms for this section. |

| 20 | An example of [~ + infinitive] is No te puedo dar una opinión ‘I cannot give you an opinion’ (CDE:19-OR, Habla Culta: Lima). |

| 21 | Here, “direct object” refers to a direct object noun phrase or clause that follows the particular verb under consideration. An example of [~ + direct object] is tengo un amigo que es el director de la revista. ‘I have a friend that is the director of the journal’ (CDE:19-OR, Habla Culta Buenos Aires). |

| 22 | [~ + other continuation (e.g., pause)] included continuations that consisted of prepositional phrases, subordinate clauses, adverbials, and pauses. An example of this is si yo voy a un país ‘if I go to a country’ (CDE:19-OR, Habla Culta: Bogotá). |

| 23 | Here, [Cl+V] refers to all clitics regardless of case and person/number (e.g., me, te, se, lo/s, la/s, le/s) that precede the particular verb under consideration |

| 24 | Third-person singular jumped from 50% in the 15th century to 90% in the 19th century, and reached 100% in the 18th century (Garachana and Hernández 2017, p. 133). |

| 25 | [haber que + infinitive] was used with personal value 100% until the 15th century and went to 90% impersonal in the 16th century. |

| 26 | One variable that Davies introduced to the study of Contemporary Spanish was the nature of the preceding material. He replicated what was true for older stages of Spanish, namely that constructions preceded by the subordinating conjunction que ‘that’ appear in proclitic position more often than with the coordinating conjunction y ‘and’. |

| 27 | Other cases include: resulta que + infinitive (CDE:19-OR, Entrevista (ABC)), Pensaba yo que + infinitive (CDE:19-OR, Entrevista (ABC)), …cajón de sastre del que + infinitive (CDE:19-OR, Entrevista (ABC)). |

| 28 | All examples belong to the Corpus de Habla Culta de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires (Barrenechea 1987) and appear followed by the conversation number (XXXI), then the page number (439), and finally the paragraph number (1). |

| Construction | % Enclisis |

|---|---|

| ir + a ‘go to’ * | 14 |

| poder ‘can/may’ * | 40 |

| querer ‘want’ | 53 |

| tener + que ‘have to’ * | 62 |

| deber ‘must’ | 68 |

| haber + que ‘must’ | 100 |

| Application Value: Enclisis | Weight | n | % | % of all Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finite Verb (p. < 4.34 × 10−8) | ||||

| tener que + Infinitive | 0.83 | 28/39 | 72 | 15 |

| empezar a + Infinitive | 0.76 | 6/10 | 60 | 4 |

| deber + Infinitive | 0.66 | 7/13 | 54 | 5 |

| querer + Infinitive | 0.60 | 8/18 | 44 | 7 |

| poder + Infinitive | 0.42 | 24/77 | 31 | 31 |

| ir a + Infinitive (movement) | 0.39 | 3/13 | 23 | 5 |

| estar + Gerund | 0.21 | 3/17 | 18 | 7 |

| ir a + Infinitive (future) | 0.14 | 5/55 | 9 | 22 |

| Range | 69 | |||

| Animacy of Referent (p. < 0.05) | ||||

| Propositional | 0.62 | 17/38 | 45 | 16 |

| Inanimate | 0.60 | 57/142 | 40 | 59 |

| Animate | 0.29 | 10/62 | 16 | 26 |

| Range | 33 | |||

| Referent Accessibility (n.s.) | ||||

| Immediately Accessible | [0.52] | 49/126 | 39 | 52 |

| Not immediately accessible | [0.48] | 35/116 | 30 | 48 |

| Topic Persistence (10 clauses) (n.s.) | ||||

| Not persistent | [0.54] | 71/196 | 36 | 81 |

| Persistent | [0.46] | 13/46 | 28 | 19 |

| N = 242, Input Probability = 0.33 (Average rate of enclisis: 35%) | ||||

| Occurrences | ||

|---|---|---|

| Following Item | Number | % |

| que + (Adv) V | 1310 | 66% |

| que + NP/nominal clause/Adv/PP | 551 | 28% |

| que + Infinitive | 122 | 6% |

| Occurrences | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceding Verb | Number | % |

| tener ‘have’ | 77 | 63% |

| haber ‘there be’ | 42 | 34% |

| Other27 | 3 | 3% |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Requena, P.E. A Usage-Based Perspective on Spanish Variable Clitic Placement. Languages 2020, 5, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5030033

Requena PE. A Usage-Based Perspective on Spanish Variable Clitic Placement. Languages. 2020; 5(3):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5030033

Chicago/Turabian StyleRequena, Pablo E. 2020. "A Usage-Based Perspective on Spanish Variable Clitic Placement" Languages 5, no. 3: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5030033

APA StyleRequena, P. E. (2020). A Usage-Based Perspective on Spanish Variable Clitic Placement. Languages, 5(3), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5030033