How the CEFR Is Impacting French-as-a-Second-Language in Ontario, Canada: Teachers’ Self-Reported Instructional Practices and Students’ Proficiency Exam Results

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Task-Based Language Teaching from an Action-Oriented Approach

2.2. The CEFR in Canadian FSL Education

- What instructional practices do a group of early-CEFR-adopter Ontario FSL teachers retrospectively report having used under Ontario’s former curriculum guidelines before having engaged in intensive and extensive CEFR-related professional learning?

- What strengths and areas for proficiency improvement are evident in the DELF exam results of a group of highly-motivated students as they prepare to graduate from their FSL studies, which took place under Ontario’s former FSL guidelines?

- What changes in instructional practices do these Ontario FSL teachers report using now under the new CEFR-informed guidelines as a result of their intensive and extensive CEFR-related professional learning?

3. Methods

4. Results

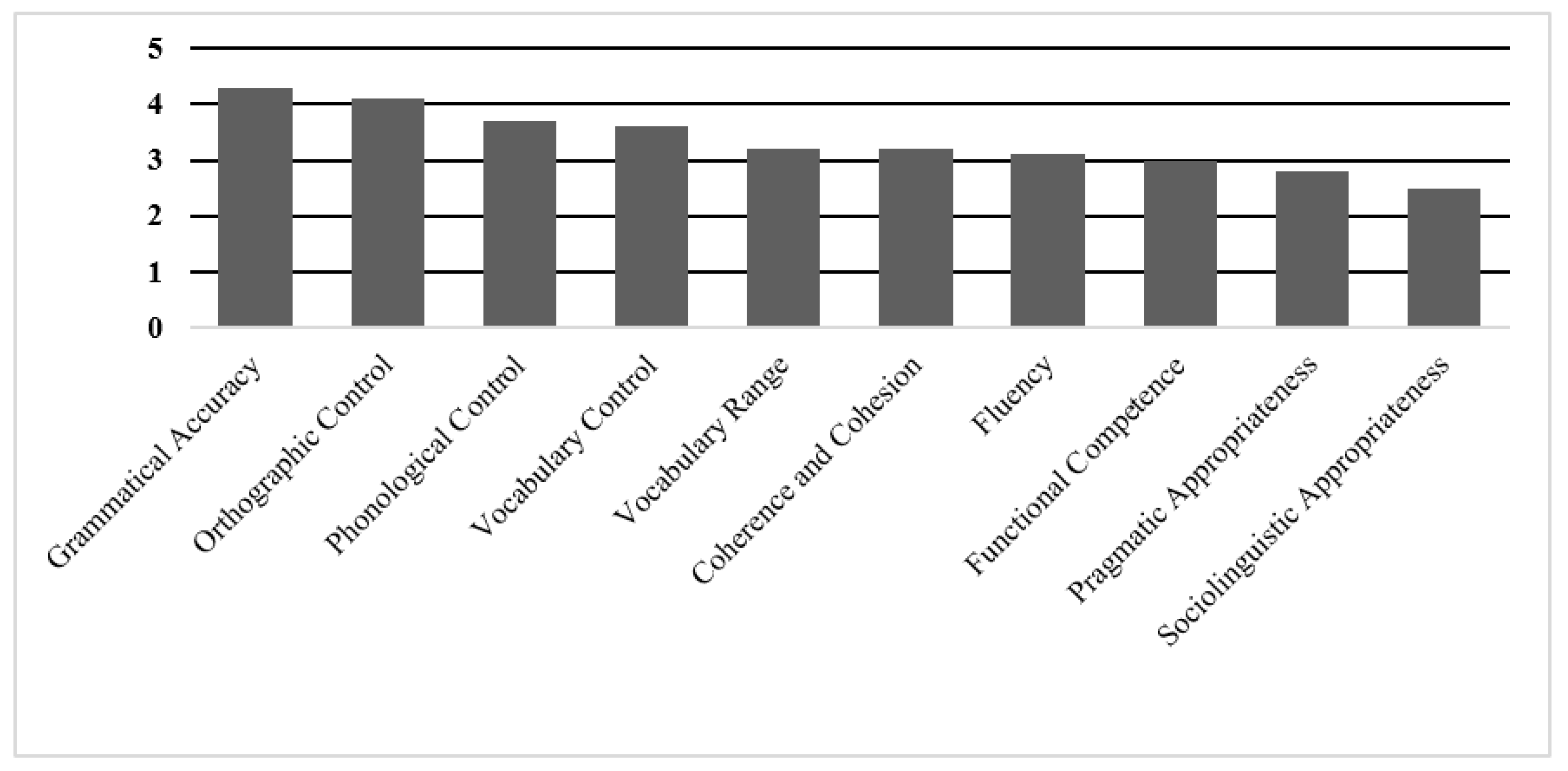

4.1. Teachers’ Retrospective Reports of Instructional Practices Prior to Their CEFR-Related Professional Learning

4.2. Strengths/Opportunities for Improvement in the DELF Results for Students under the Former Guidelines

4.3. Changes in Teachers’ Reported Practices under the Current Guidelines and after CEFR-Related Learning

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnott, Stephanie. 2013. Canadian Empirical Research on the CEFR: Laying the Groundwork for Future Research. Annotated Bibliography for the Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers/l’Association Canadienne des Professeurs de langues Secondes. Available online: https://www.caslt.org/files/pd/resources/research/2013-panorama-empiricalresearch-cefr-en.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Arnott, Stephanie, Lace Marie Brogden, Farahnaz Faez, Murielle Péguret, Enrica Piccardo, Katherine Rehner, Shelley K. Taylor, and Meike Wernicke. 2017. The common European framework of reference (CEFR) in Canada: A research agenda. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 20: 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, Claire. 2010. Pour Enseigner les Langues Avec le CECRL: Clés et Conseils. Paris: Delgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Centre International d’Etudes Pédagogiques CIEP. 2021. Detailed Information on DELF Examinations. Available online: https://www.france-education-international.fr/en/delf-tout-public/detailed-information-the-examinations (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Council of Atlantic Ministers of Education and Training. 2010. Literacy: Key to Learning and Path to Prosperity—An Action Plan for Atlantic Canada 2009–2014. Available online: https://immediac.blob.core.windows.net/cametcamef/images/eng/docs/2010%20Literacy%20Progress%20Report%20ENGLISH%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680459f97 (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- De Veaux, Richard D., Paul F. Velleman, and David E. Bock. 2011. Stats: Data and Models, 3rd ed. Boston: Pearson/Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- DestinatiONtario DELF. 2021. Parent and Student Portal for Ontario Students Preparing for the DELF. Available online: https://destinationdelf.ca/ (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Ellis, Rod. 2003. Task-Based Language Teaching and Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Rod, Peter Skehan, Shaofeng Li, Natsuko Shintani, and Craig Lambert. 2019. Task-Based Language Teaching: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faez, Farahnaz, Shelley Taylor, Suzanne Majhanovich, Patrick Brown, and Maureen Smith. 2011a. Teacher reactions to CEFR’s task-based approach for FSL classrooms. Synergies Europe 6: 109–20. [Google Scholar]

- Faez, Farahnaz, Suzanne Majhanovich, Shelley K. Taylor, Maureen Smith, and Kelly Crowley. 2011b. The power of “Can Do” statements: Teachers’ perceptions of CEFR-informed instruction in French as a second language classrooms in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 14: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1985. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Kristmanson, Paula, Chantal Lafargue, and Karla Culligan. 2013. Experiences with autonomy: Learners’ voices on language learning. The Canadian Modern Language Review 69: 462–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, David. 2006. The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Contents, purpose, origin, reception and impact. Language Teaching 39: 167–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Michael H. 1985. A role for instruction in second language acquisition. In Modelling and Assessing Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Kenneth Hyltenstam and Manfred Pienemann. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Michael H. 2014. Second Language Acquisition and Task-Based Language Teaching. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lyster, Roy, and Leila Ranta. 1997. Corrective feedback and learner uptake: Negotiation of form in communicative classrooms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 20: 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhanovich, Suzanne, Farahnaz Faez, Maureen Smith, Shelley Taylor, and Larry Vandergrift. 2010. Describing FSL Language Competencies: The CEFR within an Ontario Context. Unpublished manuscript. London: Western University. [Google Scholar]

- Mison, Sara, and In Chull Jang. 2011. Canadian FSL teachers’ assessment practices and needs: Implications for the adoption of the CEFR in a Canadian context. Synergies Europe 6: 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Moonen, Machteld, Evelien Stoutjesdijk, Rick de Graaff, and Alessandra Corda. 2013. Implementing CEFR in secondary education: Impact on FL teachers’ educational and assessment practice. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 23: 226–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, Tiffany. 2015. Professional Development Based on the New CEFR and the New Ontario French Immersion Curriculum: A Case Study of Reflective Practice. Master’s dissertation, Western University, London, ON, Canada. Unpublished work. Available online: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2827 (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Nunan, David. 2004. Task-Based Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Ministry of Education. 1980. French Core Programs, 1980: Curriculum Guidelines for the Primary, Junior, Intermediate and Senior Divisions. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Ministry of Education. 1998. The Ontario Curriculum, French as a Second Language: Core French, Grades 4–8. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Education. 1999. The Ontario Curriculum, Grades 9 and 10: French As a Second Language—Core, Extended, and Immersion French. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Education. 2000. The Ontario Curriculum, French as a Second Language—Core, Extended, and Immersion French, Grades 11 and 12. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Education. 2001. The Ontario Curriculum, French as a Second Language: Extended French, Grades 4–8; French Immersion, Grades 1–8. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Education. 2013. The Ontario Curriculum, French as a Second Language: Core French Grades 4–8, Extended French Grades 4–8, French Immersion Grades 1–8. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education. Available online: www.ontario.ca/education (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Ontario Ministry of Education. 2014. The Ontario Curriculum, Grades 9–12: French as a Second Language-Core, Extended and Immersion. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education. Available online: www.ontario.ca/education (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Piccardo, Enrica. 2013. (Re)conceptualiser l’enseignement d’une langue seconde à l’aide d’outils d’évaluations: Comment les enseignants canadiens perçoivent le CECR. Canadian Modern Language Review 69: 386–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccardo, Enrica. 2014. From Communicative to Action-Oriented: A Research Pathway. Toronto: Curriculum Services Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Piccardo, Enrica, Brian North, and Eleonora Maldina. 2019. Innovation and reform in course planning, teaching, and assessment: The CEFR in Canada and Switzerland, a comparative study. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 22: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, Katherine. 2014. French as a Second Language (FSL) Student Proficiency and Confidence Pilot Project Report 2013–2014: A Report of Findings. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education and Curriculum Services Canada. Available online: https://transformingfsl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Student_Proficiency_Full_Report.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Rehner, Katherine. 2017. The CEFR in Ontario: Transforming Classroom Practice. Research Report. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education and Curriculum Services Canada. Available online: https://transformingfsl.ca/en/resources/the-cefr-in-ontario-transforming-classroom-practice/ (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Richards, Jack C. 2013. Curriculum approaches in language teaching: Forward, central, and backward design. Relc Journal 44: 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Jack C., and Theodore S. Rodgers. 2014. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saskatchewan Ministry of Education. 2013. A Guide to Using the Common Framework of Reference (CEFR) with Learners of English as an Additional Language. Available online: http://publications.gov.sk.ca/documents/11/82934-A%20Guide%20to%20Using%20the%20CFR%20with%20EAL%20Learners.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Vandergrift, Larry. 2012. The DELF in Canada: Stakeholder Perceptions. The DELF in Canada: Stakeholder Perceptions. Ottawa: Canadian Association of Immersion Teachers. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/s/BjCjN7Sc9ycT4yAD (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Vandergrift, Larry. 2015. The DELF in Canada: Perceptions of students, teachers, and parents. Canadian Modern Language Review 71: 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, Bill. 2016. Why explicit knowledge cannot become implicit knowledge. Foreign Language Annals 49: 650–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Written Sub-Skills | Scores (x/100) | Oral Sub-Skills | Scores (x/100) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 | B1 | B2 | A2 | B1 | B2 | ||

| Follow Instructions | 92 | 87 | 80 | Phonology | 80 | 75 | 53 |

| Describe/Present Info | 78 | 76 | 63 | Respond/Share Precise Ideas | 89 | 71 | 42 |

| Coherence | 77 | 76 | 59 | Present Topic/Own View | 76 | 75 | 42 |

| Vocabulary | 73 | 64 | 53 | Vocabulary | 72 | 68 | 40 |

| Morphosyntax/forms | 62 | 51 | 46 | Morphosyntax | 68 | 62 | 40 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rehner, K.; Popovich, A.; Lasan, I. How the CEFR Is Impacting French-as-a-Second-Language in Ontario, Canada: Teachers’ Self-Reported Instructional Practices and Students’ Proficiency Exam Results. Languages 2021, 6, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010015

Rehner K, Popovich A, Lasan I. How the CEFR Is Impacting French-as-a-Second-Language in Ontario, Canada: Teachers’ Self-Reported Instructional Practices and Students’ Proficiency Exam Results. Languages. 2021; 6(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleRehner, Katherine, Anne Popovich, and Ivan Lasan. 2021. "How the CEFR Is Impacting French-as-a-Second-Language in Ontario, Canada: Teachers’ Self-Reported Instructional Practices and Students’ Proficiency Exam Results" Languages 6, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010015

APA StyleRehner, K., Popovich, A., & Lasan, I. (2021). How the CEFR Is Impacting French-as-a-Second-Language in Ontario, Canada: Teachers’ Self-Reported Instructional Practices and Students’ Proficiency Exam Results. Languages, 6(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010015