4.1. I-Language and the Nature of Amphizones

I used the term amphizone to refer to areas of transition between languages that belong to the same branch (clade), but differ in several linguistic respects. In the Ligurian/Occitan amphizone, for instance, variants are separated by a bundle of isoglosses that emerged because physical and political barriers hindered the transmission of innovative traits from one side to the other, thus yielding a fracture in the linguistic continuum. Although this fracture is perceivable by everyday speakers, it does not preclude mutual intelligibility.

The idea that contact played a pivotal role in determining how dialects are grouped dates back to the 19th century, when the predominant scientific paradigm in dialectology was the theory of layers (strata)

22. According to this view, present-day differences reflect the influence of the languages spoken before the Latinization (substratum), of the languages that were/are spoken at the boundary of the Romance area (adstratum), or of the high/roofing languages that co-exist with dialects in contexts of diglossia (superstratum). Linguistic differentiation emerged from situations of asymmetric bilingualism, leading either to borrowing from one stratum to another or to a generalized impoverishment of the Latin grammar due to attrition.

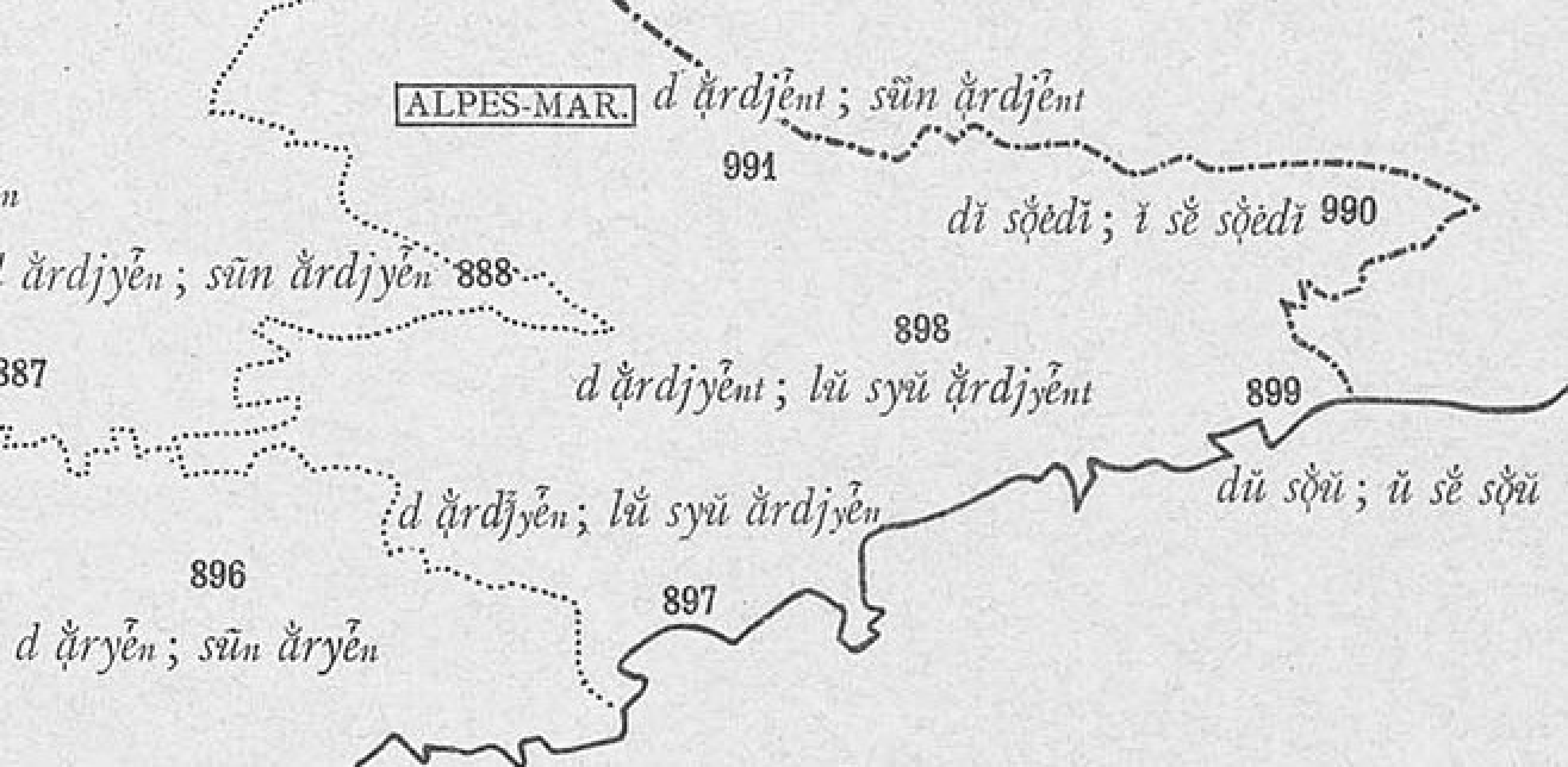

Concretely, what are the possible effects of other linguistic layers on the Occitan/Ligurian continuum? With respect to the data in

Section 2, attrition of the substratum can be safely excluded because all the traits summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 15—clitics and determiners—are innovations that emerged in the Middle Ages. One might suggest that contact with roofing languages (French or Italian) may have triggered recent changes such as the neutralization of gender distinctions in plural determiners in Nissart, e.g., fpl [li], mpl [ly] > [li] “the” (cf.

Section 2.1). At a more abstract level, I argued in

Section 3 that Nissart has a double series of possessives: D possessives like French and adjectival-like possessives like Italo-Romance. One might claim that the co-existence of two series of possessives resulted from an influence of the roofing language (French) on an underlying Italo-Romance system. All these hypotheses are difficult to test, but what is crucial for our discussion is that this kind of explanation cannot account for most of the fine-grained variation illustrated in

Section 2.

Given the nature, distribution and chronology of microphenomena (at all levels, syntactic, morphological, phonetic, lexical, etc.), the strata hypothesis needs to be tempered. Hugo Schuchardt (1842–1927; see, for instance,

Schuchardt 1870) was the first to propose a more nuanced model of change and variation, by arguing that the Romance area is a linguistic continuum and that differences resulted from several waves of innovations that spread in multiple directions across space and time. The kind of theory envisaged by Schuchardt was revived in 20th century sociolinguistic approaches in which endogenous change results from contact between dialects (i.e., sociolinguistic varieties) within the same language (see

Milroy (

1992, p. 88) a.o.). Notice that, in the latter view, languages are conceived as a social construct, whereas the strata hypothesis is rooted in a Darwinian approach, in which languages are seen as living entities, independent from the community of speakers.

I do not intend to elaborate further on the long-lasting debate about layers vs. waves, but what is relevant for our purposes is that the two approaches to language diversity presuppose two very different conceptions of contact. In the former (layers), contact refers mainly to the coexistence of languages that are unrelated or belong to distinct branches of the phylogenetic tree (interclade contact, according to my terminology) and presupposes two conditions that are not necessarily met in intraclade contact: bilingualism and borrowing. In fact, speakers from an

amphizone are not necessarily dialect/dialect bilingual (or bidialectal). Nowadays, most speakers acquire both their local dialect and a roofing language (either Italian or French), but they do not acquire two dialects belonging to, e.g., the Occitan and the Italo-Romance subgroups

23. Leaving roofing languages aside, it is questionable whether speakers of the past have ever learnt more than a local dialect. I mentioned in

Section 1 that some 19th century speakers of the Riviera were able to communicate in Genoese, which has been the contact language of sailors and traders for centuries, but I doubt that inhabitants of inland centres ever learnt the dialect of their neighbours as in fully fledged contexts of bilingualism. Dialect speakers probably adapted their E-language in the same way in which speakers shift from a linguistic register to another, depending on the characteristics of the hearer. Avoiding the most local/rural phonetic and lexical features was probably enough to communicate with members of nearby linguistic communities.

Similar considerations hold for the notion of “borrowing”. The various linguistic communities that populate the amphizone have evolved in parallel and the similarities we observe nowadays do not result because one language borrowed a given trait from another. For instance, it is unlikely that the co-occurrence of articles and possessives in Nissart is a borrowing from Ligurian (as folk linguists usually suggest). In fact, in the absence of sound historical documentation, one cannot affirm that similarities result from contact-induced change with a nearby variety.

Hence, most features of contact that characterise interclade situations (e.g., bilingualism, attrition, borrowing, etc.) do not seem relevant in intraclade contact. Does this amount to saying that contact is irrelevant for the structural evolution of the varieties in question?

In short, my answer is that, despite intra- and interclade contact result from different conditions, intraclade contact has important effects on the structural evolution of dialects. As

Schuchardt (

1884, p. 5) put it, “[t]here is no completely unmixed language” and, in rephrasing Schuchardt’s intuition, let us assume, following generative theorizing, that syntactic change/variation always results from the

transmission (or failures thereof) of linguistic traits across time/space (see

Kroch (

2001) and references therein). The key notion here is “transmission”: I have already argued that the transmission of features in intra- and interclade contact situations follows different paths. Similarities and differences within an

amphizone, for instance, did not emerge because adult speakers of one village learnt the language of a neighbouring village and/or failed in learning their neighbours’ dialects and ended up with an attrited language. This scenario is highly implausible, given the socio-historical conditions of the area.

Instead, consider that all the dialects spoken in an

amphizone emerged from the same language—in our case, a regional variant of vulgar Latin. More technically, varieties emerged via selection of specific features from a common pool of variants: a variant, for instance, regarding how mass singulars and indefinite plurals are introduced, either by α)

de or β)

de + Art. Notice that transitional varieties are not those in which both variants are attested. Despite dialects exhibiting fine-grained variation, there is no single variety that exhibits free variation between two alternative variants of the same structure. For instance, with respect to the phenomena illustrated in

Table 1, no dialect allows

optional subject clitics, or permits either ordering of complement clitics.

Analogously, the dialects of the

amphizone do not allow articles and possessives to co-occur optionally: the two types of modifiers are either in complementary distribution or must co-occur. The same holds true for all the other microphenomena overviewed in

Section 2 and summarized in

Table 15. Hence, isoglosses may overlap, but, once single syntactic traits are examined, we observe that syntactic variation always results from discrete choices and free variation does not really exist.

At the same time, however, it is worth noting that the distribution of two competing variants is never 0% vs. 100%. For instance, in

Section 2.2, we noticed that Nissart adopts (α), although (β) is marginally attested in cases of nominal ellipsis of the kind illustrated in (6)c (repeated here as (28)c; Gasiglia 1984).

| (28) | a. | Vouòli *dou vin. (Niss) |

| | | ‘I want (some) wine.’ |

| | b. | Vouòli *dou vin rouge. |

| | | ‘I want (some) red wine.’ |

| | c. | Vouòli dou vin rouge |

| | | ‘I want (some) red wine.’ |

Analogously, we observed that the generalization that Nissart prenominal possessives (excluding the D possessives that introduce kinship nouns) do not agree holds true for monosyllabic forms, whereas disyllabic possessives are regularly inflected (cf. (14) = (29)):

| (29) | a. | la mieu(*a) cadièra | vs | a’. | la nouòstr*(a) cadièra (Niss.) |

| | | ‘my chair’ | | | ‘our chair’ |

| | b. | li mieu(*i) cadièra | vs | b’. | li nouòstr*(i) cadièra |

| | | ‘my chairs’ | | | ‘our chairs’ |

Possessives introducing kinship nouns are another case in point: they are normally found only with non-modified singular kinship terms, but—crucially—the list of kinship terms occurring in article-less NPs is subject to cross-dialectal variation.

All the above examples show that recessive variants are not expelled from linguistic systems, but remain in the periphery of the grammatical “space”: sometimes they are confined to a certain stylistic register or are associated with specific lexical items or to specific pragmatic values. In a scenario like this, surrounding languages are expected to play a role in the selection of linguistic traits to the extent that social contacts affect the number of speakers that, in each community, bear a certain linguistic trait. The higher the number of speakers carrying a given variant α, the more likely the possibility that future generations exhibit α.

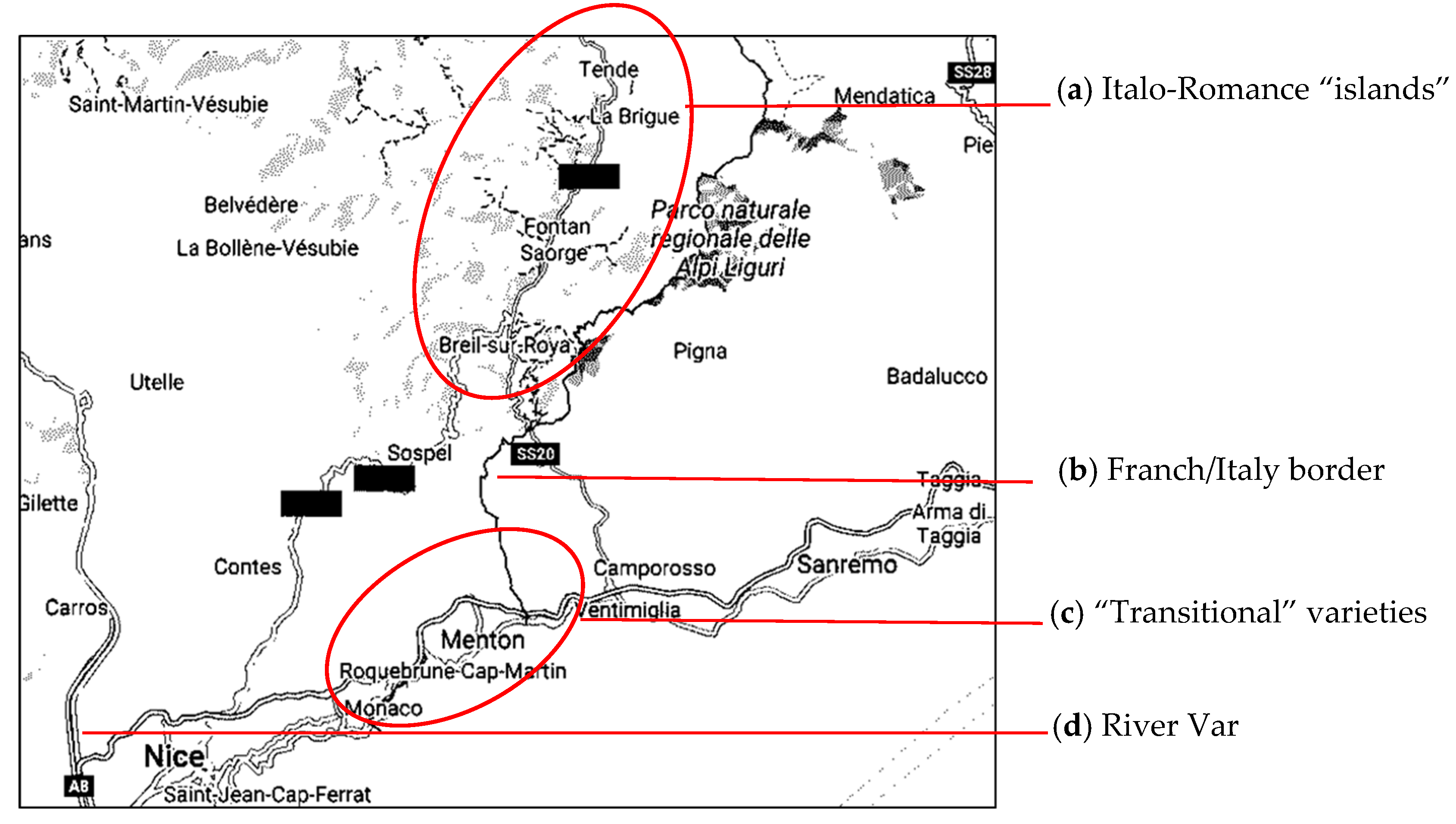

Physical or political barriers, as in the case of the Alpes-Maritimes, hinder social contacts and, consequently, hinder the transmission of variants between communities: recessive features will therefore remain at the periphery of the system, while dominant variants will be passed to new generations. This lack of transmission yields the bundle of isoglosses that, a posteriori, we conceptualize as the

amphizone between Occitan and Italo-Romance dialects. Social relations, however, are not completely disrupted and certain localities—in our case, those situated on the coast—exhibit

transitional characters. Transitional characters emerge when communities can select their features from a richer pool of variants because the continuous admixture of speakers from various provenance affects the relative incidence of variants: recessive traits can eventually become dominant (or vice versa), depending on either sociolinguistic factors (e.g., prestige) or, possibly, internal factors (more on this in

Section 4.2).

To conclude, the conditions yielding intraclade contact differ from those entailed in contexts of interclade contact. Concepts such as bilingualism, attrition, borrowing, etc., are rather problematic in the former case. From an I-language perspective, interclade contact presupposes a complex interaction between co-existing grammars, whereas it seems to me that the emergence of transitional varieties through intraclade contact presupposes a less direct role of the faculty of language in the selection of dominant and recessive traits.