1. Introduction

The Stockholm archipelago is an area famous for its natural beauty. It is also an area of contrasts: At the same time a relatively remote and rural location at the fringes of the Baltic Sea, and yet close to the urban centres of the capital region of Sweden. The many islands of the archipelago are sparsely populated for most of the year, with a large influx of seasonal residents, as well as other visitors from the city and beyond, during the summer months. All these groups of people can also potentially leave their marks on the linguistic landscapes of the islands, as will be discussed in this article.

Although there are some common nominators between the linguistic landscapes in focus in the present study and those discussed in previous research, it is difficult to find exact parallels to the situation seen in the Stockholm archipelago. On the one hand, the focus of the majority of studies in the field has been on urban localities (cf.

Van Mensel et al. 2017, p. 423). On the other hand, in the cases where studies have taken an interest in more rural locations, they have been concerned with far more remote landscapes (e.g.,

Pietikäinen et al. 2011, on villages in the arctic). Such is the case even with studies on island locations,

Mühlhäusler and Nash (

2016), for example, discuss the linguistic landscape and onomastics of Norfolk Island in relation to tourism and power relations reflected on signs.

The effect tourism can have on the linguistic landscape is another possible point of contact with previous studies. As mentioned, especially in summer, the Stockholm archipelago is filled with different kinds of visitors. However, whether they are out there sailing, enjoying the nature of the islands on a day trip, or staying some months at their summer houses, this tourism is still quite local in nature. Thus, the effects of the visitors, at least concerning language use, are less controversial than those highlighted in some previous cases.

Moriarty (

2012,

2015) has, for example, discussed the contested language practices in the linguistic landscape of an Irish tourist town. There the linguistic landscape becomes a focal point of the language political debate on the roles of Irish and English, and between the views of the local population and the tourism industry. Across the Baltic Sea from the Stockholm archipelago,

Marten et al. (

2012) have discussed the linguistic landscapes of tourism in the Baltic states. There, too, the interest lies in the role of the linguae franca (Russian and English) tourism has brought with it to the landscape.

However, even without such politically contested issues, the linguistic landscape can be linked to the very concept of (creating and identifying) meaningful

places (cf.

Cresswell 2015), or in other terms,

social spaces (

Lefebvre 1991).

Scollon and Scollon (

2003), in defining the role of place semiotics, already point out how signs obtain part of their meaning from where they are located, and how the signs in turn can index the semiotic spaces they are placed within. As such, various notions of spatiality have engaged scholars of linguistic landscapes (for further discussion, see e.g.,

Van Mensel et al. 2017, pp. 437–39). For the purpose of this present study, I will be more specifically drawing from

Lefebvre’s (

1991) theories on socially produced space.

Building partly on the concepts of Lefebvre,

Stjernholm (

2015) uses the commercial signscapes of Oslo to discuss the

sense of place in two different districts of the city. This notion of the linguistic landscape reflecting a specific sense of place is also raised by e.g.,

Jaworski and Yeung (

2010) discussing naming and the semiotic landscape of residential Hong Kong.

Ben-Rafael (

2009, p. 42) in turn reflects on how linguistic landscape is a major contributor to the perceived “personality” of a given locality. As

Stjernholm (

2015, p. 78) summarizes it, the “

sense of place is seen as a perceptible product of a socially constructed space where people’s lives are reflected in the physical environment, making space a contextualizing force where sociocultural meaning is expressed.” Thus, considering the signs of the linguistic landscape allows us to gain an understanding of the functions and identities of specific places beyond language use.

Conceptualizing the notion of social space,

Lefebvre (

1991, pp. 38–40) crucially identifies three different aspects of space:

The spatial practice of a society, which can be “deciphered” by considering the material reality, the perceived space.

Representations of space from the minds of planners—or, indeed, of commercial interests. The conceived space realized in verbal signs is the dominant space of any society or mode of production.

Representational space, corresponding to the lived space of its inhabitants and users.

This description of perceived, conceived, and lived space should, however, not be seen as a fixed model of separate concepts, but rather as interconnected realms of the space produced in any society (

Lefebvre 1991, p. 40). In terms of the linguistic landscape, what we see is of course a part of the perceived space. As

Lefebvre (

1991, p. 38) notes, this space must be cohesive to a certain degree, but not coherent, i.e., logically conceived as a whole. This is the case with linguistic landscapes as well, with there being signs in the first place, and those partly consisting of signs explicitly reproducing the conceived space (through advertising, for example), while the lived space is more covertly present through non-verbal symbols and signs (cf.

Lefebvre 1991, p. 39).

It is of course important to remember the difference between the actual social spaces and what is represented in the linguistic landscape. As

Cresswell (

2015, p. 18) points out, “We do not live in landscapes—we look at them.”

Lefebvre (

1991, p. 116) himself reminds that social space is not a subject or an object to be analysed, but a complex social reality. One should thus distinguish it from just things in space or ideas about space. A complete picture of the space any society produces must therefore consider both the lived and conceived space, as well as their relationship with each other and to the (material) spatial practice (

Lefebvre 1991, p. 53). While the theoretical notions on the history, production, and reproduction of space could be discussed in length, in the present context, suffice it to point out the connection

Lefebvre (

1991, p. 77) makes between the forces of production and space, thus highlighting the importance of both economical and sociocultural aspects.

As commercial language use is often central in linguistic landscapes, the theoretical framework of forces of production becomes highly relevant while considering the different aspects of space through the lens of the linguistic landscape.

Stjernholm (

2015, p. 79), among others, highlights how the producers of signs need to consider the market and their audience, that is, the lived and perceived spaces, to form the conceived space and be able to make profit from the linguistic landscape. For a critical analysis of demand and command,

Lefebvre (

1991, p. 116) therefore points to the need of questions such as “who” and “for whom” to be asked of the lived, conceived, and perceived spaces. This, I would argue, is not only relevant in urban settings, but also in relation to more rural linguistic landscapes, such as those considered in the present study. Asking to whom the linguistic landscape “speaks” presents an opportunity for a critical view of the sense of place to which it contributes to.

The study of linguistic landscapes is of course not the only field within linguistics concerning itself with the

sense of place. Such a concept is of key importance within dialectology, for example. While it is not relevant to delve into that field of study in this present article, it is interesting to note how even there the urban versus rural divide can be critically discussed in relation to language and space (cf.

Britain 2017). In the cross-section of these fields,

Östman (

2017) discusses dialectal signs in the linguistic landscape in Ostrobothnia. Through his case study, he raises questions about identity and authority. When the bottom-up signs are replaced by top-down items, the linguistic landscape becomes less about the identity of local individuals and more about an appropriation of a “brand” of the community (

Östman 2017). In Lefebvre’s terms, the linguistic landscape in different degrees thus reflects the different aspects of the social spaces (and a certain sense of place). In a similar vein, studies on tourism and linguistic landscapes often raise the question of

authenticity.

Moriarty (

2015), for example, describes how the specific language use is not necessarily reflecting (a lived space of) the Irish minority, but used to index it as an authentic tourist destination (i.e., an outsider’s conceived space).

Building on these theoretical concepts, the aim of the present study is to critically discuss if a certain sense of place is reflected (or produced) by the linguistic landscapes of two islands in the Stockholm archipelago. To this end, a qualitative analysis will focus on two main research questions: (1) How is this kind of (rural) linguistic landscape constructed? (2) Does the linguistic landscape mainly speak to the permanent residents, or to the visitors? In other words, I’m interested in both what kind of signs can be found, what languages are used, and what kind of information is mediated, and, crucially, if the linguistic landscape reflects the islands as a lived space or produces a conceived space of the tourism industry and other commercial interests.

2. Materials and Methods

The materials used for this study were collected in July 2021 from the linguistic landscapes on two islands in the Stockholm archipelago, Nämdö and Svartsö. These islands were chosen for the study as they represent medium-sized islands of the archipelago that are only accessible by boat. They also share some other key characteristics: Both islands are served by public transportation to several jetties, and they feature different kinds of local businesses (restaurants, small grocery stores, a hostel), as well as some official services (a school on Svartsö, and a library, a church, and a small museum on Nämdö). The year-round population of about 25 people on Nämdö and about 70 on Svartsö (

Värmdö municipality 2018a,

2018b) is complemented by a large number of summer residents. The islands also attract other visitors, especially Nämdö, where a large part of the island consists of a nature reserve.

To form a basis for the qualitative discussion, all stationary signs with visible text along a pre-planned route on each island were photographed. Thus, the data collection follows similar principles as many previous studies within the field (cf.

Van Mensel et al. 2017, pp. 439–41). Non-verbal signs were excluded from the data: While such signs can contribute to a specific sense of place, only a few such signs (occasional traffic signs) were observed in the landscapes in question. In all, the material thus consists of a total of 581 signs. This includes 334 signs from Nämdö, collected on a 4.5-kilometre walk from Sand to Östanvik via Solvik, and 247 signs from Svartsö, similarly collected on a 4-kilometre walk between Skälvik and Norra Svartsö.

Previous (quantitative) studies of linguistic landscapes have considered a number of different ways to categorize signs in order to describe the properties and functions of a linguistic landscape. At the same time, the difficulties in finding a universal solution have also been noted (cf.

Amos and Soukup 2020). For example,

Blackwood (

2015, p. 41) describes a typology of nine categories based on the functions that the signs perform, thus including (1) business names; (2) business signs; (3) graffiti; (4) information; (5) instructions; (6) labels on products; (7) legends; (8) street names; and (9) trademarks. However,

Blackwood (

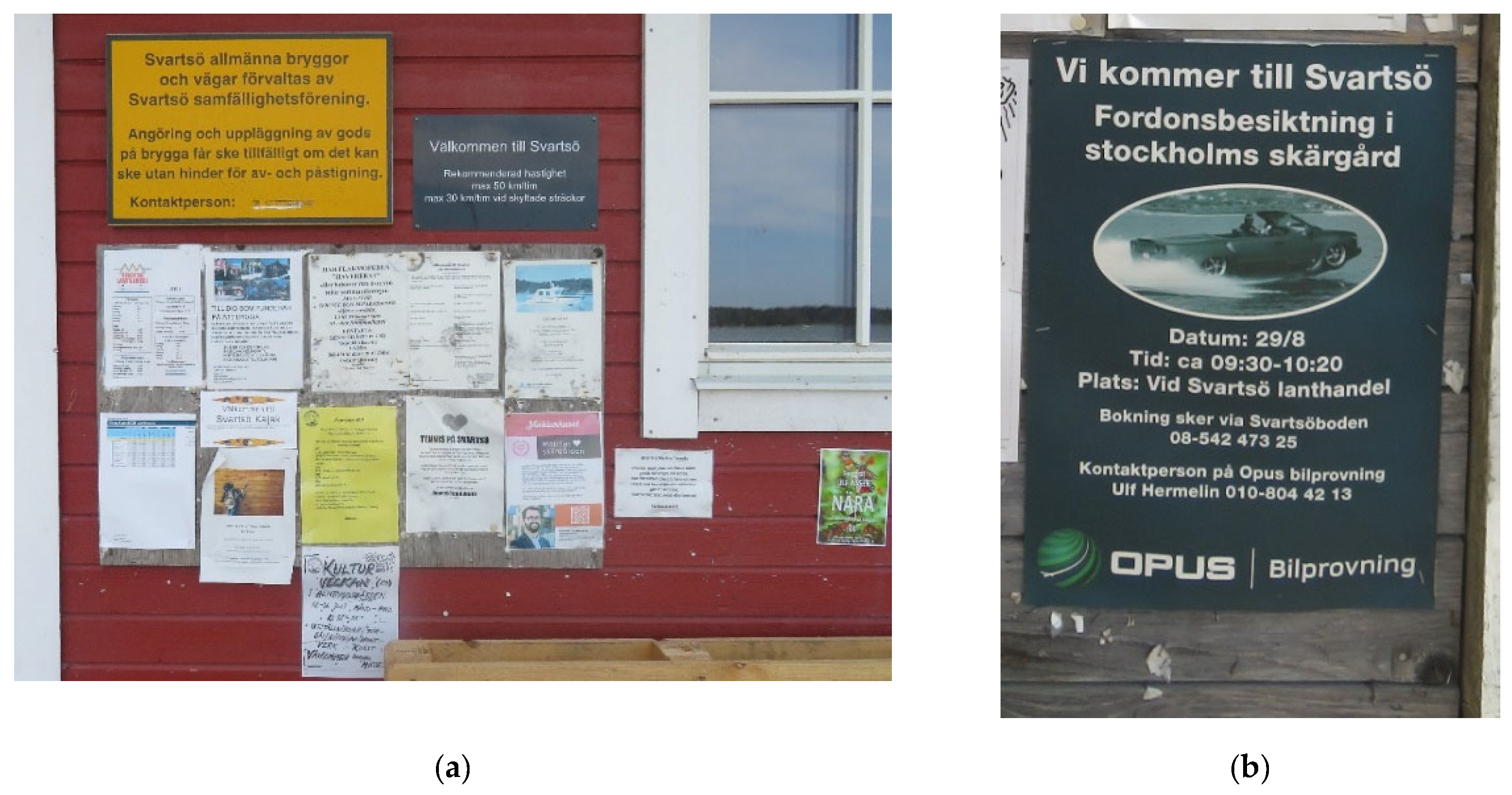

2015, p. 41) also points to the flaws of the typology encountered during fieldwork, especially the fact that signs might fulfil different functions simultaneously. Furthermore, in the case of the linguistic landscapes discussed in the present study, for example, such a typology would focus disproportionately on qualities of commercial signs, while more subtle differences within e.g., messages on bulletin boards would be lost.

Amos and Soukup (

2020) propose a set of variables for more standardized quantitative studies of linguistic landscapes, but as the perspective of the present study is more qualitative, with a focus on the signs as texts rather than just language choice, any such complex solutions were not deemed useful for the purpose of this article.

Instead, a simpler categorization of the signs will be used for the first part of the analysis. There I partly build on the solutions in the study of

Nord (

2017) discussing a Swedish university building as a “textual environment”. By taking a more text analytic approach,

Nord (

2017, p. 72) considers the

text assemblage points (‘textsamlingspunkter’ in Swedish) that can be identified in the landscape, as well as the functions of the different texts and by whom they are written. As will be explained more in

Section 3.1 below, I will also describe the linguistic landscapes based on the locations and overall functions of the signs found therein, in addition to analysing the languages used. Then, in

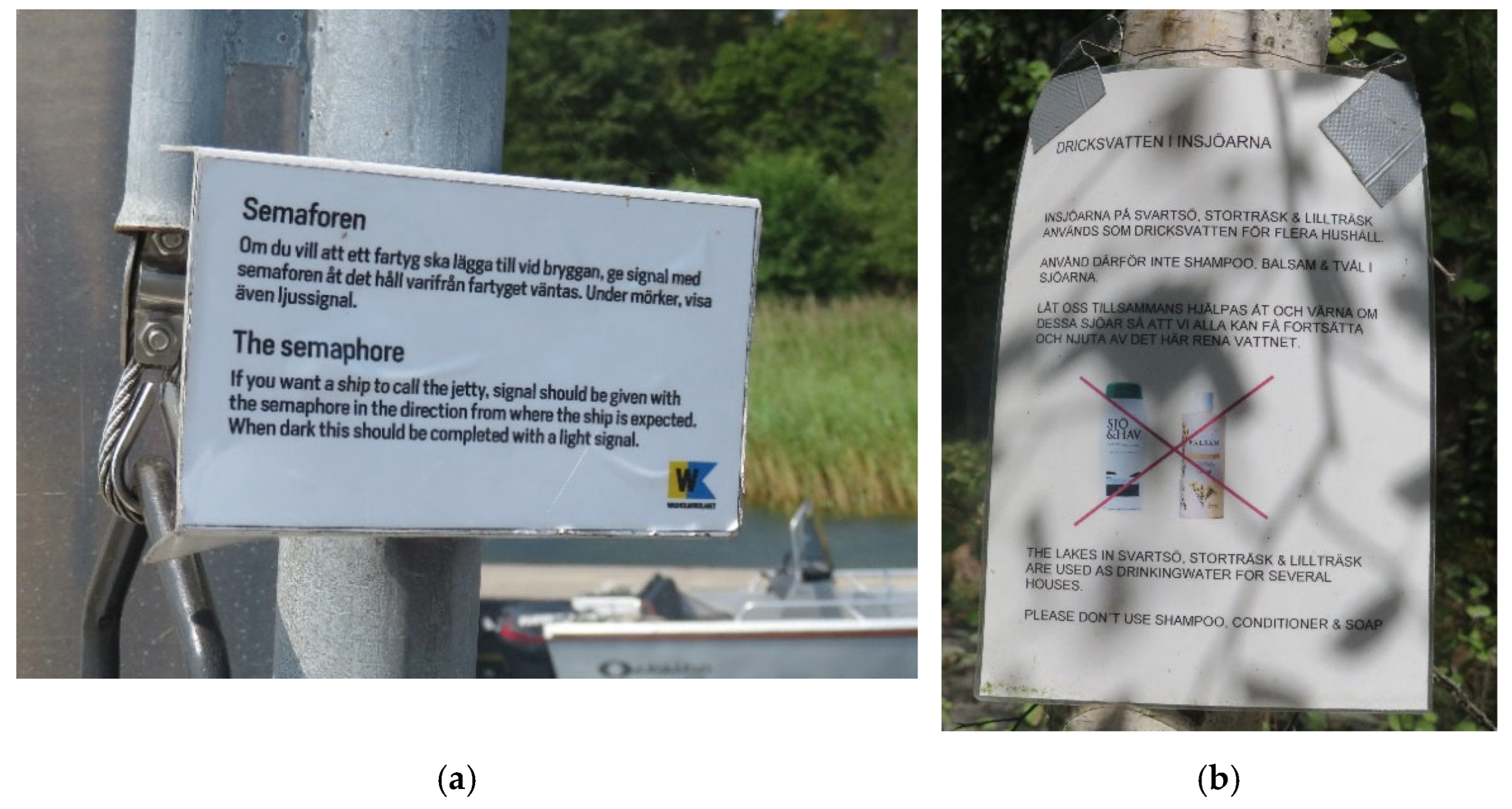

Section 3.2, I will take a closer look at some examples of relevant signs to discuss the intended audiences of these signs as a way to approach the sense of place they contribute to.

4. Discussion

The findings of the qualitative analysis presented in this article highlight both the unique nature of the linguistic landscapes of the Stockholm archipelago and the usefulness of linguistic landscapes for gaining insights into the production of social spaces. While the more rural linguistic landscapes analysed are sparse on signs compared to urban settings, the landscape still addresses multiple audiences, both the permanent residents of the islands and those visiting. The linguistic landscape is not overrun by commercial interests, thus producing and reflecting a sense of a place that is quite local and, in some senses, understated. Even if I would be careful with using the term authenticity based on the present study alone, it can at least be concluded that the linguistic landscapes in question feel more organic, rather than overly produced.

While discussing the effect of tourism on the linguistic landscapes,

Kallen (

2009, p. 276) noted that an area with a small local population can seem more intensively touristic than a larger city, as the linguistic landscape becomes more easily saturated with such outside input. That is thus not the case with the linguistic landscapes of Nämdö and Svartsö. Although most of both the residents and visitors of the islands are Swedish speaking, the results showing how monolingually Swedish the landscapes are is still somewhat surprising. Considering how widely English is used in both the Swedish society at large and within the tourism sector, and even the observations

Laitinen (

2014) made about the use of English in rural landscapes, its limited visibility here must be considered unexpected.

Furthermore, although no linguistic data on the visitors are available, there are certainly even non-English speakers among those visiting the islands (as evidenced e.g., by sailboats from several countries seen in the archipelago). Even though a number of visitors come to Nämdö and Svartsö during the summer, there are of course more touristic places in the Stockholm archipelago, such as Sandhamn, that might (and do) have another type of linguistic landscape altogether. In those cases, more marketing-oriented efforts can reflect a slightly more multilingual linguistic landscape. The reasons for the complete invisibility of languages such as Finnish or German, or the limited number of examples of the use of English, cannot, however, be found on the signs themselves. On the signs discussed in the present study, the language choice still more or less coincides with the contents (i.e., main audiences) of the signs as discussed above. In this way, the linguistic landscape in part enforces the dominance of the (mainly Swedish speaking) residents over the spaces in question. One should still be careful to draw definitive conclusions on prestige or other sociolinguistic aspects without further ethnographic data.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, the present study has illustrated the relatively remote and sparse linguistic landscapes of Nämdö and Svartsö where a considerable part of the signage can be found at certain text assemblage points (cf.

Nord 2017), such as bulletin boards. The linguistic landscape speaks to both the permanent residents and visitors to the islands in different ways, as exemplified in the analysis above. As the signs observed are mainly monolingual, a more qualitative look at the functions/contents of the signs is central in addition to the question of language choice to gain insight to the social spaces they reflect. While the present study has given us a glimpse of the more authentic (in the sense of rural and more local) landscapes of Nämdö and Svartsö, there is yet more to observe to fully understand the Stockholm archipelago or to account for further meaningful semiotic aspects of the signs.

Considering the theoretical aspects of the present study, a critical approach through the linguistic landscape allows us to reflect on the production of social spaces beyond the material reality of perceived space. The conceived spaces taking form in the signs relate to different groups of individuals present in the social space. We can also gain hints of the lived spaces in the linguistic landscape, and thus an understanding of what is pertinent to life in the archipelago. As much of the lived space is experienced beyond the textual representations, ethnographic perspectives could be a useful addition in further studies to be able to capture more of such aspects of the production of social space. Likewise, as the qualitative analysis presented in this article has only scraped the surface of the different signs, and of what they have to tell about the spatial practices of the society, a more in-depth (and multimodal) text analytic approach to the items found in the linguistic landscape would be interesting. In such a way, more light could be shed on the conceived and perceived space and e.g., the societal struggles of who is visible and who is not in a certain place and its landscape.

Referring back to

Lefebvre (

1991), as the different aspects of social space are not separate from each other, the perceived space (and the linguistic landscape) is thus a product of input from different individuals, local associations, businesses, official actors, etc. What can be concluded from the present study, I would argue, is that some of the observations on lived and conceived spaces could not be possible in other kinds of linguistic landscapes, such as those in urban settings and more saturated with commercial messages. Therefore, as

Moriarty (

2015, p. 211) points out, it is important to include data from more peripheral linguistic landscapes. That might be rather crucial to see past the economically motivated forces of production dominating many spaces (and linguistic landscapes). Lastly, I would argue that this study helps to acknowledge that to gain an understanding of a sense of place, reflecting upon the linguistic landscape can be a relevant tool, even—or perhaps especially—in settings that are not as multilingual as those of most studies.