Taboo Language in Non-Professional Subtitling on Bilibili.com: A Corpus-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Taboo Language

- (1)

- Sexual references;

- (2)

- Profane or blasphemous references;

- (3)

- Scatological referents and disgusting objects;

- (4)

- Ethnic–racial–gender slurs;

- (5)

- Insulting references to perceived psychological, physical, or social deviations;

- (6)

- Ancestral allusions;

- (7)

- Substandard vulgar terms; and

- (8)

- Offensive slang;

入境而问禁,入国而问俗,入门而问讳 (《礼记.曲礼上》)Inquire about the legal prohibitions when entering a country, inquire about the customs when entering a metropolis, inquire about the unmentionables when entering a residence.(Translated by Jing-Schmidt 2019)

2.2. Taboo Language in AVT

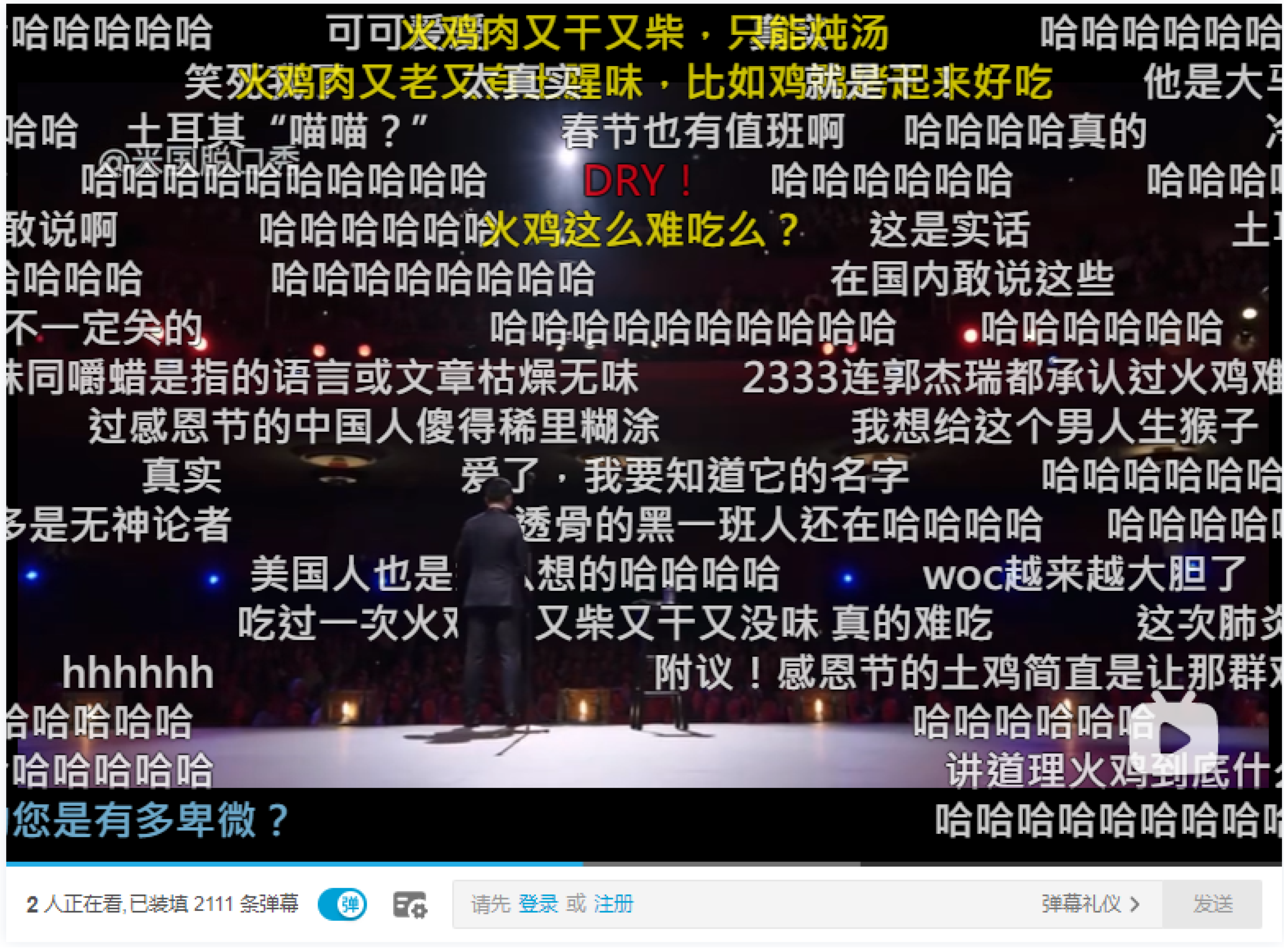

2.3. Translation Activities in Bilibili.com

2.4. Subtitling Strategies and Techniques and Effects

3. Materials & Methods

- The original language of the video is English.

- The subtitles are either in Chinese only or in Chinese and English.

- The video has more than one taboo language.

- The view count is more than one million.

- The number of danmu comments is more than 1000.

- (1)

- Taboo language is usually toned down in professional subtitling. Given the creative and individualistic nature, what are some of the most used subtitling strategies and techniques in rendering taboo language in non-professional settings?

- (2)

- How do subtitle viewers react to the renderings of taboo language provided by non-professional subtitlers? How do the interactions between danmu and general comments contributors potentially affect the translation activities and language changes?

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Positive Feedback

ST: All you need is rice, a pot, and this fucking line right here.TT: 你所需要的就是大米、一个锅、以及中指上的这条线BT: All you need is rice, a pot, and this line on your middle finger.Nine danmu comments are made right after this punchline, and five of them compliment this brilliant rendering:Danmu 1: 中指好评Danmu 1 BT: Great job on the “middle finger”Some feedback is even more in-depth and inspiring. In Michael Che’s video (Video 12, Appendix A), he talked about racism:ST: We all need Asian people because they make shit affordable.TT: 我们都需要亚洲人,因为他们的东西物美价廉BT: We all need Asian people because their stuff is good quality and reasonably priced.

4.2. Neutral Feedback

ST: (I actually liked the religion). I would convert if it would not for the policies on titties and bacon.TT: 要不是因为他们对奶*和培根的特殊规定,我都想加入他们了.BT: I would convert if it would not for the ti** and bacon policies.Danmu 1: 奶油含有猪油Danmu 1 BT: Cream has lard in it.Danmu 2: Titty.Danmu 3: 前面的不是奶油好吗,是那个奶Danmu 3 BT: It’s not cream, okay? It’s boobs.

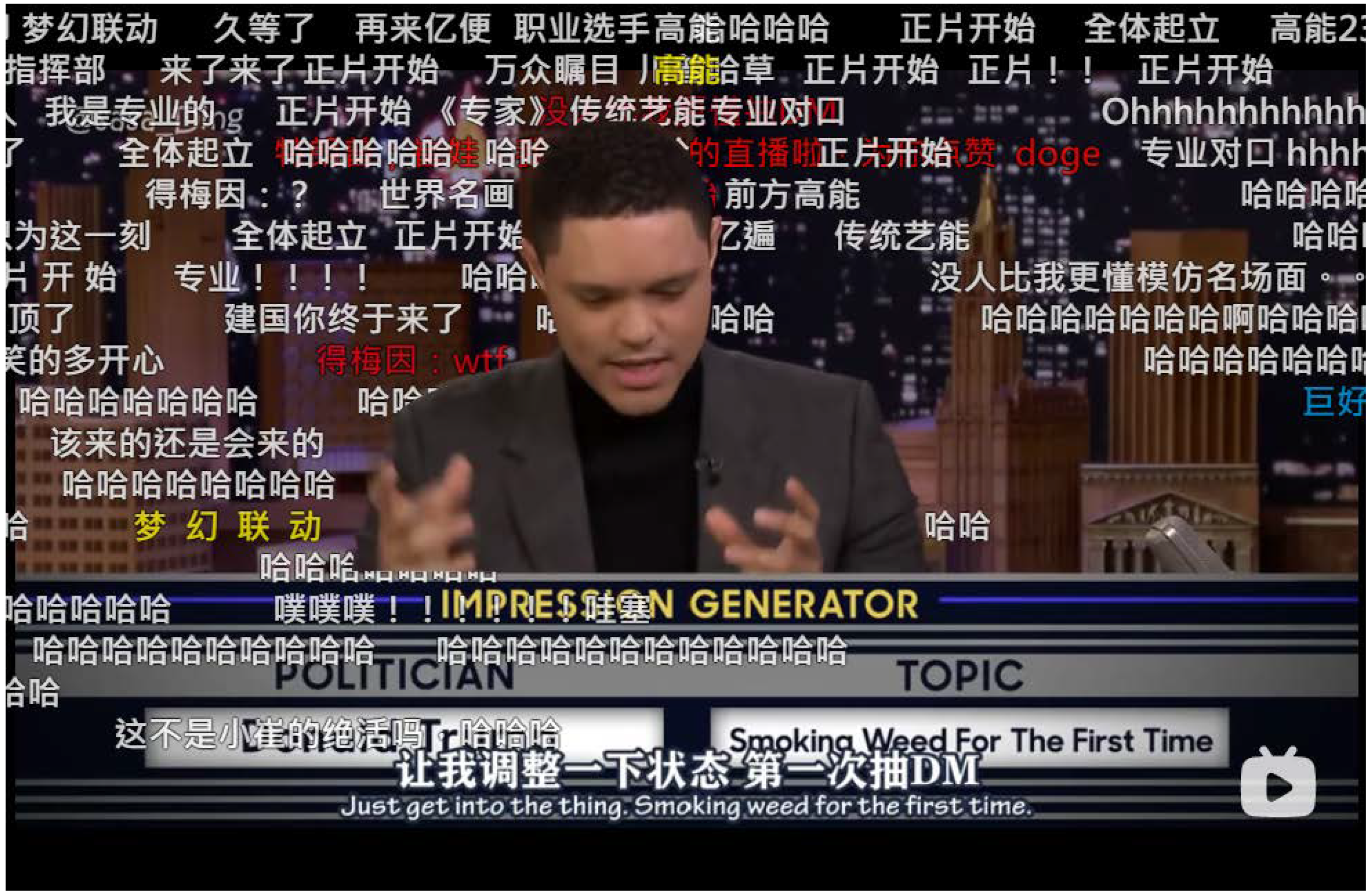

Danmu 1: 草(植物)Danmu 1 BT: Grass (a plant)Danmu 2: 说杂草的认真的吗哈哈哈哈Danmu 2 BT: You said grass? Are you being serious, hahahaDanmu 3: 特朗普开始抽大麻了Danmu 3 BT: Trump is smoking weed.Danmu 4: weed = dama

4.3. Constructive Criticism

ST: You can’t be more badass than that.TT: 还有比这更操蛋的事情么?!BT: Can it be more fucked up?!

Danmu 1: 翻译错了,badass应该翻译成还有比他更狠的人Danmu 1 BT: The translation is wrong. Badass should refer to someone tough.Danmu 2: Badass有厉害的意思Danmu 2 BT: Badass can mean fierce.

ST: It helps you if you don’t have a family, Jimmy!TT: 可能单身的人可以节省一些“精”力吧BT: Maybe single people can have more “jing” li.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Significance and Future Directions

5.2. Limitation

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Video List

| No. | Translated/Shortened Title | View Count (Million) | Number of danmu Comments | Link | Genre |

| 1 | Trevor imitating Trump! | 1.3 | 3619 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1y7411X7Df/?spm_id_from=333.788.videocard.0 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Late-night TV show |

| 2 | Foreigners don’t understand how the Chinese use one finger to measure rice water. | 4.04 | 12k | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1z4411c7hT/?spm_id_from=trigger_reload (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

| 3 | Trevor teasing Trump. | 2.14 | 4088 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1RW411Y7rv/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.1 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Late-night TV show |

| 4 | Joe Wang’s Stand-up Comedy Work of Fame. | 1.36 | 4420 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1yt411h7Pq?from=search&seid=5096238003153256128&spm_id_from=333.337.0.0 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

| 5 | China, baby! | 26 | 59k | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV144411n7vZ/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.2 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Late-night TV show |

| 6 | Can’t go back to China to see my wife and enjoy the food. | 2.85 | 9586 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV165411x71K/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.12 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Independent uploader |

| 7 | How much do Americans know about China? | 1.06 | 13k | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1qa4y1x7gU/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.0 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Independent uploader |

| 8 | Chinese man doing stand-up comedy abroad. | 1.28 | 1764 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1bx411r7XU?from=search&seid=6499257030100239600&spm_id_from=333.337.0.0 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

| 9 | The most incomprehensible Chinese word. | 3.95 | 8459 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1qb41137E5/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.5 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Late-night TV show |

| 10 | Can the yellow race call black people “nigger”? | 1.5 | 1075 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1hb411j7XG/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.0 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

| 11 | Children speak the truth. | 8.24 | 3313 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1V4411f7LL/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.3 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Compiled videos |

| 12 | The most warm-hearted racism. | 1.19 | 2018 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1Yt411G7cX/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.9 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

| 13 | Funny clip of Benedict Cumberbatch. | 5.45 | 4326 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV16t4y1z7yH/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.0 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Late-night TV show |

| 14 | Chinese people respecting the elderly. | 1.81 | 2443 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1o4411x7RK/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.15 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

| 15 | Fired by the gang for being too positive. | 1.81 | 1420 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1vE411A71b/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.13 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

| 16 | Dated a gay man somehow. | 1.63 | 4480 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV16T4y1N7VC/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.0 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

| 17 | America needs an Asian President. | 1.17 | 2906 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1VJ41157Qq/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.23 (accessed on 16 December, 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

| 18 | Chinese people love money. | 1.2 | 2951 | https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1dJ411J7DL/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.35 (accessed on 16 December 2021) | Stand-up comedy |

References

- Al-Jabri, Hanan, Areej Allawzi, and Abdallah Abushmaes. 2021. A Comparison of Euphemistic Strategies Applied by MBC4 and Netflix to Two Arabic Subtitled Versions of the US Sitcom How I Met Your Mother. Heliyon 7: e06262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, Keith, and Kate Burridge. 1991. Euphemism & Dysphemism: Language Used as Shield and Weapon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, Keith, and Kate Burridge. 2006. Forbidden Words: Taboo and the Censoring of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alsharhan, Alanoud. 2020. Netflix’s No-Censorship Policy in Subtitling Taboo Language from English into Arabic. Journal of Audiovisual Translation 3: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yasin, Noor F., and Ghaleb A. Rabab’ah. 2019. Arabic Audiovisual Translation of Taboo Words in American Hip Hop Movies: A Contrastive Study. Babel Revue Internationale de La Traduction/International Journal of Translation 65: 222–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, Saeed, and Khalil Ghazizadeh. 2015. A Norm-Based Analysis of Swearing Rendition in Professional Dubbing and Non-Professional Subtitling from English into Persian. Iranian Journal of Research in English Language Teaching 2: 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Cabrera, José Javier. 2015. An Account of the Subtitling of Offensive and Taboo Language in Tarantino’s Screenplays. Sendebar 26: 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Cabrera, José Javier. 2016. The Treatment of Offensive and Taboo Terms in the Subtitling of ‘Reservoir Dogs’ into Spanish. Málaga: TRANS, pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Cabrera, José Javier. 2017. La subtitulación del lenguaje ofensivo y tabú. Estudio descriptivo. In Fotografía de la Investigación Doctoral en Traducción Audiovisual. Edited by Juan José Martínez Sierra. Madrid: Bohodón Ediciones, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Cabrera, José Javier. 2020. Profanity and Blasphemy in the Subtitling of English into European Spanish: Four Case Studies Based on a Selection of Tarantino’s Films. Quaderns 27: 125–41. [Google Scholar]

- Beseghi, Micòl. 2016. WTF! Taboo Language in TV Series: An Analysis of Professional and Amateur Translation. Altre Modernità 2016: 215–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilibili. 2018. BiliBili开始支持CC字幕(软字幕)啦!—哔哩哔哩. Available online: https://www.bilibili.com/read/cv1368832 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Bilibili. 2020. B站转正答案100题哔哩哔哩转正考试答题答案—哔哩哔哩. Available online: https://www.bilibili.com/read/cv7051093 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Bilibili. 2021. 关于我们—哔哩哔哩. Available online: https://www.bilibili.com/blackboard/aboutUs.html (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Briechle, Lucia, and Eva Duran Eppler. 2019. Swearword Strength in Subtitled and Dubbed Films: A Reception Study. Intercultural Pragmatics 16: 389–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Sin-wai. 2016. The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Chinese Language. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chiaro, Delia. 2009. Issues in audiovisual translation. In The Routledge Companion to Translation Studies. Edited by Jeremy Munday. London: Routledge, pp. 141–65. [Google Scholar]

- China Tech Express. 2020. Bilibili Releases 2020 Influencer Report–Nativex. Available online: https://www.nativex.com/en/blog/china-tech-express-bilibili-releases-2020-influencer-report/ (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Costales, Alberto Fernández. 2012. Collaborative Translation Revisited: Exploring the Rationale and the Motivation for Volunteer Translation1. FORUM. Revue Internationale d’interprétation et de Traduction/International Journal of Interpretation and Translation 10: 115–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Cintas, Jorge, and Aline Remael. 2007. Audiovisual Translation: Subtitling. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Cintas, Jorge, and Aline Remael. 2021. Subtitling: Concepts and Practices. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Perez, Francisco Javier. 2020. Translating Swear Words from English into Galician in Film Subtitles. Babel 66: 393–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, Margherita, and Angelica Petrucci. 2021. Professional and Amateur AVT. The Italian Dubbing, Subtitling and Fansubbing of The Handmaid’s Tale. Perspectives 8: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Chong, and Kenny Wang. 2014. Subtitling Swearwords in Reality TV Series from English into Chinese: A Corpus-Based Study of The Family. Translation & Interpreting 6: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Gyde. 2010. Integrative Description of Translation Process. In Translation and Cognition. Edited by Gregory M. Shreve and Erik Angelone. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- He, Zhengguo. 2018. Multiple Causality of Differences in Taboo Translation of Blockbuster Films by Chinese Fansubbers and Professionals; Newcastle University. Available online: http://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/handle/10443/4284 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Hughes, Geoffrey. 2006. An Encyclopedia of Swearing: The Social History of Oaths, Profanity, Foul Language, and Ethnic Slurs in the English-Speaking World. New York: M.E. Sharpe. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Timothy. 2009. The Utility and Ubiquity of Taboo Words. Perspectives on Psychological Science 4: 153–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Crespo, Miguel A. 2017. Crowdsourcing and Online Collaborative Translations: Expanding the Limits of Translation Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Jing-Schmidt, Zhuo, and Shu-Kai Hsieh. 2019. Chinese Neologisms. In The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Applied Linguistics. New York: Routledge, pp. 514–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jing-Schmidt, Zhuo. 2019. Cursing, Taboo, and Euphemism. In The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Applied Linguistics. New York: Routledge, pp. 391–406. [Google Scholar]

- Khakshour Forutan, Moein, and Ghasem Modarresi. 2018. Translation of Cultural Taboos in Hollywood Movies in Professional Dubbing and Non-Professional Subtitling. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 47: 454–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshsaligheh, Masood, Milad Mehdizadkhani, and Saeed Ameri. 2016. Through the Iranian Fansubbing Glass: Insights into Taboo Language Rendition into Persian. Paper presented at Audiovisual Translation: Dubbing and Subtitling in the Central European Context, Nitra, Slovakia, June 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Lisi. 2020. Subtitling Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001) in a Chinese Context: The Transfer of Sexuality and Femininity in A Chick Flick. International Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies 8: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, Sondre. 2013. Translate This, Motherfucker! Master’s thesis, Universitetet I Oslo, Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Magazzù, Giulia. 2018. Non-Professional Subtitling in Italy: The Challenges of Translating Humour and Taboo Language. Córdoba: Hikma, vol. 17, pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nornes, Markus. 1999. Toward an Abusive Subtitling: Illuminating Cinema’s Apparatus of Translation. Film Quarterly 52: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hagan, Minako. 2009. Evolution of User-Generated Translation: Fansubs, Translation Hacking and Crowdsourcing. The Journal of Internationalization and Localization 1: 94–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hagan, Minako. 2012. From Fan Translation to Crowdsourcing: Consequences of Web 2.0 User Empowerment in Audiovisual Translation. Leiden: Brill, pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Orrego-Carmona, David, and Yvonne Lee. 2017. Non-Professional Subtitling. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Orrego-Carmona, David. 2015. The Reception of (Non)Professional Subtitling. Doctoral Diss, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Orrego-Carmona, David. 2016. Internal Structures and Workflows in Collaborative Subtitling. In Non-Professional Interpreting and Translation in the Media. Edited by Rachele Antonini and Chaira Bucaria. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 231–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, Jan. 2011. Subtitling Norms for Television: An Exploration Focusing on Extralinguistic Cultural References. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Pratama, Agus. 2017. The Functions of Taboo Words and Their Translation in Subtitling: A Case Study in ‘The Help’. RETORIKA: Jurnal Ilmu Bahasa 2: 350–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pym, Anthony. 2011. What Technology Does to Translating. Translation & Interpreting 3: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Cheng 任骋. 1991. Chinese Folk Taboos 中国民间禁忌. Beijing: Zuojia Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, Colin. 2002. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Julia Navegantes de Saboia. 2016. A tradução de palavrões nas legendas de True Blood: The translation of swear words on True Blood’s subtitles. Rónai—Revista de Estudos Clássicos e Tradutórios 4: 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Trupej, Janko. 2019. Avoiding Offensive Language in Audio-Visual Translation: A Case Study of Subtitling from English to Slovenian. Across Languages and Cultures 20: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdeón, Roberto A. 2020. Swearing and the Vulgarization Hypothesis in Spanish Audiovisual Translation. Journal of Pragmatics 155: 261–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajnryb, Ruth. 2005. Expletive Deleted: A Good Look at Bad Language. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, MicKayla. 2021. Taboo and Offensive Language in Audiovisual Translation: A Spanish to English Case Study of the Television Series Paquita Salas. Diss, University Honors College Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Yuhong. 2021a. Danmaku subtitling: An exploratory study of a new grassroots translation practice on Chinese video-sharing websites. Translation Studies 14: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yuhong. 2021b. Making Sense of the ‘Raw Meat’: A Social Semiotic Interpretation of User Translation on the Danmu Interface. Discourse Context & Media 44: 100550. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Yiyi, and Anthony Fung. 2017. Youth online cultural participation and Bilibili: An alternative form of democracy in China? In Digital Media Integration for Participatory Democracy. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 130–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Long. 2015. The Subtitling of Sexual Taboo from English to Chinese. London: Imperial College London. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Leticia-Tian, and Daniel Cassany. 2020. Making Sense of Danmu: Coherence in Massive Anonymous Chats on Bilibili.Com. Discourse Studies 22: 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Strategies | Definition | Expected Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Partial omission | Parts of taboo language are omitted in the TT. | Toning down |

| 2 | Complete omission | No taboo language is omitted in the TT. | Toning down |

| 3 | Retention | The foreign word or phrase is retained in the TT. | Toning down |

| 4 | Lexical recreation in TT | Neologism is observed in the TT. | Toning down |

| 5 | Direct translation | All features of the ST are kept in the TT. | Maintaining |

| 6 | Substitution by euphemism | Taboo language is substituted by euphemism in the TT. | Toning down |

| 7 | Addition | Taboo language is not observed in the ST but is added to the TT. | Toning up |

| Category | Number (Source) | Number (Added) | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abusive swearwords | 26 | 3 | Fuck the police |

| Expletives | 9 | 2 | Damn! |

| Profane/blasphemous | 0 | ||

| Animal name terms | 0 | ||

| Ethnic/racial/gender slurs | 7 | 1 | nigger |

| Sexual/body part references | 11 | 1 | Barack Obama giving the sex talk |

| Urination/scatology | 1 | 1 | pee |

| Filth | 0 | ||

| Drugs/excessive alcohol consumption | 1 | 0 | Smoking weed |

| Violence | 0 | ||

| Death/killing | 0 | ||

| Invectives | 0 | 2 | 我这副德性 (de xing) |

| Other | 0 | 1 | 新guan病毒 |

| ST | TT | Danmu Comments | General Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Smoking weed | 吸DM | Weed = 杂草 | 抽DM(暗物质) 可还行 |

| 说杂草的认真的吗哈哈哈 | 突然让我想起来老友记里甘瑟抽钱德勒那跟烟的台词 | |||

| Da ma可还行hhh | 特朗普:没有人比我更懂DM!吸溜~吸溜~吸溜 |

| No. | Strategies | Expected Effects | Number of Instances (in Percentage) | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Partial omission | Toning down | 3 (4.7%) | ST: fuck TT: 你X的 BT: fXk |

| 2 | Complete omission | Toning down | 8 (12.5%) | ST: What the hell is laser? TT: 镭射是什么? BT: What is laser? |

| 3 | Retention | Toning down | 2 (3.1%) | ST: it’s made gay TT: gay息太浓了 |

| 4 | Lexical recreation in TT | Toning down | 15 (23.4%) | ST: What the hell! TT: TM的 |

| 5 | Direct translation | Maintaining | 10 (15.6%) | ST: big butt TT: 大屁股 BT: big butt |

| 6 | Substitution by euphemism | Toning down | 15 (23.4) | ST: sex TT: 啪啪啪 papapa |

| 7 | Addition | Toning up | 11 (17.2%) | ST: bad fall TT: 摔个狗吃屎 BT: fall like a dog eating shit |

| No. | Expected Effects | Number of Instances (in Percentage) | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Toning down | 43 (67.2) | ST: fuck TT: 你X的 BT: fXk |

| 5 | Maintaining | 10 (15.6%) | ST: big butt TT: 大屁股 BT: big butt |

| 7 | Toning up | 11 (17.2%) | ST: bad fall TT: 摔个狗吃屎 BT: fall like a dog eating shit |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X. Taboo Language in Non-Professional Subtitling on Bilibili.com: A Corpus-Based Study. Languages 2022, 7, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020138

Chen X. Taboo Language in Non-Professional Subtitling on Bilibili.com: A Corpus-Based Study. Languages. 2022; 7(2):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020138

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xijinyan. 2022. "Taboo Language in Non-Professional Subtitling on Bilibili.com: A Corpus-Based Study" Languages 7, no. 2: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020138

APA StyleChen, X. (2022). Taboo Language in Non-Professional Subtitling on Bilibili.com: A Corpus-Based Study. Languages, 7(2), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020138