2. Relevant Background on Aspect and the Research Problem

Aspect, being one of the three major verbal categories (next to tense and modality) in the languages of the world, expresses “ways of viewing the internal temporal constituency of a situation” (see

Comrie 1976, p. 3). In research on aspect, scholars distinguish between lexical aspect and grammatical aspect. Lexical aspect is inherently encoded in the lexical meaning of verbal predicates, and it corresponds to

Vendler’s (

1957) classification of lexical aspectual classes, also referred to as Aktionsart: states (e.g.,

love,

understand), activities (e.g.,

work,

run), accomplishments (e.g.,

build a castle,

eat a sandwich), and achievements (e.g.,

notice,

find a solution), which were later extended to a lexical aspectual class of semelfactives (e.g.,

wink,

sneeze) by

Smith (

1991). Grammatical aspect (also referred to as viewpoint aspect) is explicitly coded by aspectual morphemes. According to

Dahl (

1985), grammatical aspect manifests itself most commonly as the perfective and imperfective opposition. In languages that have a deficient system of grammatical aspectual morphology, aspectual meaning is computed mainly based on lexical aspect, while in languages that possess a wide range of aspectual morphology, aspectual meaning is composed based on the interaction between lexical aspect (aspectual class), where perfective and imperfective aspectual operators act as eventuality description modifiers (see

de Swart 1998). Germanic literature on aspect focuses primarily on lexical aspect because Germanic languages have a deficient system of aspectual morphology, with some Germanic languages possessing only the grammatical markers of progressive aspect. By contrast, in the Slavic linguistic tradition more attention has been paid to grammatical aspect because Slavic languages possess a wide range of aspectual markers (markers participating in aspect coding). In Slavic languages almost all finite and non-finite verb forms are either perfective or imperfective and most verbs have both aspectual variants, as shown in (1).

| (1) | | | | |

| ukrainian | Ia čytalaI | /pročytalaP | tvoje | ese. |

| belarusian | Ia čytałaI | /pročytałaP | tvajo | ese. |

| russian | Ia čitalaI | /pročitalaP | tvojo | esse. |

| slovak | ČítalaI | /prečítalaP som | tvoju | esej. |

| czech | Já jsem četlaI | /přečetlaP | tvoji | esej. |

| polish | CzytałamI | /przeczytałamP | twój | esej. |

| slovene | BralaI | /prebralaP sem | tvoj | spis. |

| serbian | ČitalaI | /pročitalaP sam | tvoj | esej. |

| croatian | ČitalaI | /pročitalaP sam | vaš | esej. |

| bulgarian | ČetohI | /pročetohP | tvoeto | ese. |

| macedonian | Go čitavI | /pročitavP | tvojot | esej. |

| | (I) read.ipfv.1sg.f/read.pfv.1sg.f | your | essay |

| | ‘I was reading/read your essay.’ |

According to

Comrie (

1976), perfective aspect describes an eventuality as a complete whole whereas imperfective aspect focuses on the internal temporal structure of an eventuality. The two most canonical readings of imperfective in Slavic are single ongoing and plural event one. In more formal semantic approaches, perfective aspect involves a temporal perspective that locates the temporal trace of an event within the reference time, while the imperfective involves a temporal perspective that falls inside an event that, in turn, excludes the event endpoints from view (see also

Reichenbach 1947;

Comrie 1976;

Kamp and Reyle 1993;

Klein 1995;

Smith 1991;

Kratzer 1998;

Borik 2006;

Kazanina and Phillips 2003).

The use of perfective and imperfective aspect varies across Slavic. In order to understand the variation it is necessary to be aware of the basic classification of Slavic languages and their geographical distribution. The group of Slavic languages is divided into three subgroups:

South Slavic, consisting of Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, Serbian, Slovene, Bulgarian, and Macedonian;

West Slavic, consisting of Czech, Slovak, Sorbian, Polish, and Kashubian; and

East Slavic, consisting of Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian. The geographical distribution of the regions in which Slavic languages are spoken is shown in

Figure 1.

In spite of the considerable micro-typological variation in tense–aspect grammars of Slavic languages, most Slavic aspectologists have developed the semantics of aspect based on the data from a single language. One of the attempts to study the semantics of grammatical aspect in Slavic from a comprehensive comparative perspective was made by

Dickey (

2000,

2015,

2018a,

2018b,

2020), who offers a micro-typology of Slavic aspect based on the evaluation of data from Bulgarian, Macedonian, Czech, Polish, Russian, Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian (BCS), Slovak, Slovene, and Ukrainian. On the basis of the differences observed in the distribution of perfective and imperfective aspect in a range of contexts (habitual, general-factual, imperative, performative, deverbal nouns, running instructions),

Dickey (

2000) proposes

the ‘East-West theory of Slavic aspect’. More precisely, he proposes a division of the Slavic languages into a western group consisting of Czech, Slovak, Sorbian, and Slovene, and an eastern group consisting of Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Bulgarian. BCS and Polish are claimed to belong to transitional zones, with Polish tending towards the eastern group and BCS patterning closer to the western group, while Bulgarian displays some deviations from the eastern group.

Dickey (

2015) revised his original view slightly and claimed that the extremes of the East–West opposition are to be found in North Slavic: (i) the western extreme includes primarily West Slavic languages (Czech, Slovak, Sorbian) and only one peripheral South Slavic language (Slovene) and (ii) the eastern extreme consists of East Slavic (Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian). Polish and BCS occupy transitional positions between the eastern and western types (Polish and Serbian are closer to the eastern type, whereas Croatian is closer to the western type). Macedonian is still closer to the eastern type than Serbian. Bulgarian matches the eastern type for the basic parameters, but it differs from the eastern extreme in some important ways (see

Dickey 2015, p. 32). The East–West aspect division proposed by

Dickey (

2015) is schematically represented in

Figure 2.

Among the contexts, which according to

Dickey (

2000 and subsequent works) are subject to cross-Slavic variation, are the so-called general-factual contexts that constitute the biggest challenge for aspect theories because, in these contexts, completed events may be expressed by means of imperfective aspect.

4. The Study

In order to elicit aspect choices in the tested general-factual contexts, an online scenario-based elicitation questionnaire was conducted where respondents were asked to fill in the missing verbs in Polish, Czech, and Russian.

4.1. Participants

125 respondents from Poland, 135 respondents from Czech, and 86 respondents from Russia filled in the questionnaire.

4.2. Procedures

The experiment was uploaded to the survey platform

https://www.google.pl/intl/pl/forms/about/ (accessed on 2 May 2022) and it was sent to different colleagues in Poland, Czech Republic, and Russia with the request to distribute them among their students, friends, and further colleagues. Additionally, in order to reach a high number of participants, the links were made available on Facebook. Participants were asked to fill in the missing verbs using contextual information and English infinitival verb forms

8 given in the brackets as cues, as shown in

Figure 3.

The following instruction was used:

Dear participant, in the contexts below, please write the correct form of the verb (the first form that comes to mind after reading the whole context). The verbs should be written in Polish. The missing word in English is given in brackets as an indication of the word in question. Sometimes there is a note next to the English word (past), which means that the verb has to be used in the past tense. Thank you very much for your time.

The instruction was written in the native language of the respondents.

4.3. Material

The questionnaire consisted of 30 experimental scenarios and 22 filler scenarios (see

Appendix A for all the contexts tested in the study). The original version of the tested contexts was created in Polish and it was translated to Russian and Czech. The translations were corrected by native speakers of these languages. The fillers contained time-span adverbials, durative adverbials, or phase verbs like ‘begin’ or ‘finish’, which elicited specific aspect choices. The fillers were used to mislead the respondents as to the purpose of the experiment and to make aspect choices in factual contexts as unconscious as possible. The tested contexts and the distractors were pseudo-randomized. There were six types of factual contexts, all of which contained accomplishment verbs (see

Table 1).

9The questionnaire was anonymous. Additionally, information about the age group and the region of origin was elicited from the respondents. The mean age in Czech was 30.4 with an age range from 19 to 72. The mean age in Russian was 39.2 with an age range from 18 to 67. The mean age in Polish was 29.2 with an age range from 20 to 67. In the cover letter to the participants, we specified that we want the questionnaire to be filled in by a native speaker of the tested languages.

Below the tested types of contexts are presented and discussed in more detail.

4.3.1. Existential Factual Contexts

An example of

a neutral existential factual context is provided in (24).

| | Polish | | | | |

| (24) | a. | To nie jest | wielki | wyczyn | |

| | | it not is | big | achievement |

| | | użyć | nowoczesnej | kosiarki | do trawnika. |

| | | use.inf | modern | mower | to lawn |

| | | Ciekawe, | czy Jan | kiedyś | |

| | | interesting | if John | ever | |

| | | kosiłI | trawnik | prawdziwą |

| | | mowed.ipfv.3sg.m | lawn.acc | real.inst | |

| | | kosą. | | | |

| | | scythe.inst | | | |

| | Czech | | | | |

| | b. | Použít | moderní | sekačku | na trávu |

| | | using | modern | mower | to lawn |

| | | Neni | žádný | velký | výkon. |

| | | is not | any | big | achievement |

| | | Zajímalo by | mě, | zda někdy | Jan |

| | | interest cond | me | if ever | John |

| | | sekalI | trávu | opravdovou |

| | | mowed.ipfv.3sg.m | lawn.acc | real.inst | |

| | | kosou. | | | |

| | | scythe.inst | | | |

| | Russian | | | | |

| | c. | Ispoľzovanije | sovriemiennoj | gazonokosilki |

| | | using | modern | lawn-mower |

| | | – eto nie | podvig. | | |

| | | – it not | achievement | | |

| | | Intieriesno, | kosilI | | |

| | | interesting | mowed.ipfv.3sg.m | |

| | | li | Jan | | |

| | | Q | John | | |

| | | kogda-nibuď | travu.acc | nastojaščej real.inst |

| | | ever | lawn |

| | | kosoj? | | | |

| | | scythe.inst | | | |

| | | ‘It’s no great feat to use a modern lawn mower. I wonder if John has ever mowed a lawn with a real scythe?’ |

In this context, the existence of the past event of

mowing, denoted by the verbal predicate, is focused (it is not backgrounded). The use of the adverbial

ever requires that there is at least one instantiation of the past event within some interval that extends from some point in the past until now. The adverb also requires that the temporal location of the past event(s) is arbitrary (non-specific). The location of the past event is vague (non-specific, indefinite). The QUD is whether the event

ever happened, hence the indefiniteness of the past event is under discussion. Previous discourse is neutral, and it does not make the result state of the past event relevant for the current discussion in contrast to the resultative existential factual contexts in (25). In fact, these contexts match

Padučeva’s (

1996) “general-factual resultative contexts”.

An example of

a resultative existential factual context is provided in (25):

| | Polish | | | | |

| (25) | a. | Widzę, że | kwiatki | na parapecie | |

| | | see.1sg that | flowers | on ceiling | |

| | | zwiędłyP. | Czy ty | na pewno | |

| | | wilted.pfv.3pl | Q you | for sure | |

| | | je | dzisiaj | podlewałeśI? | |

| | | them.acc | today watered.ipfc.2sg.m |

| | Czech | | | | |

| | b. | Vidím, že | kytka | na římse | zvadlaP. |

| | | see.1sg that | flowers | on ceiling | wilted.3pl.pfv |

| | | Určitě jsi | je | dnes | zalívalI? |

| | | sure be.2sg | them | today | watered.ipfv.2sg.m |

| | Russian | | | | |

| | c. | Ja vižu, čto | cviety | na podokonnikie | zasoꭓliP. |

| | | I see.1sg that | flowers | on ceiling | wilted.pfv.3pl |

| | | Ty uvierien, | čto | polivalI | iꭓ |

| | | you certain | that | watered.ipfv.2sg.m | them |

| | | segodnia?10 | | | |

| | | today | | | |

| | | ‘I can see that the flowers on the window-sill have wilted. Are you sure you watered them today?’ |

In (25) the existence of the past event, denoted by the verbal predicate water, is focused (it is not backgrounded). There is potentially at least one instantiation of the past event within the interval that extends from some point today until now. The adverb today does not locate the event at a specific point on the time axis but, in contrast with (24), the result of the past event in (25) is causally related to the speaker's earlier observation that the flowers wilted. This is expected to facilitate the choice of perfective aspect in these contexts even though the past event can be located relative to some indefinite time point within a broad time span provided by the adverb today.

4.3.2. Presuppositional Factual Contexts

The presuppositional factual scenarios used in the current study start from a sentence outlining a topic situation held at the moment of speaking, followed by a wh-question presupposing the existence of a past event and asking about some details related to either the object or the initiator of the past event. The presupposed past event is in an Elaboration relation with the event or state introduced in the preceding sentence.

Two factors were manipulated:

Discourse-level: the QUD was related either to the holder of the result state or to the initiator of the event. When the QUD is related to the initiator of the past event, the emphasis is shifted away from the result state, and hence we may expect more choices of imperfective.

Verb-level: the use of creation verbs and non-creation accomplishment verbs where only the former guaranteed that the reaching of the result state was a necessary (strong) epistemic precondition for the existence of the holder of the result state.

This resulted in four types of presuppositional factual contexts: (i) strong resultative presuppositional factual context focusing on the initiator (srp-init), (ii) strong resultative presuppositional factual context focusing on the result (srp-res), (iii) weak resultative presuppositional contexts (wrp-init), and (iv) weak resultative presuppositional factual context (focusing on the result) (wrp-res).

In strong resultative presuppositional contexts, creation verbs leading to the existence of the object were used, e.g., sew, build, paint, draw, cook, bake, sculpt, as exemplified in (26) and (27). In (26), the focus is on the result sub-event, and in (27), the focus is on the initiation sub-event.

Strong resultative presuppositional factual context, focus on the result| | Polish | | | | |

| (26) | a. | Jaki pyszny | placek | Marysiu. | |

| | | how delicious | cake | Mary | |

| | | Z jakich | składników | go | piekłaśI? |

| | | with which | ingredients | it.acc | baked. ipfv.2sg.f |

| | Czech | | | | |

| | b. | Ta placka | je skvělá, | Maryšo. | |

| | | this cake | is delicious | Mary | |

| | | Z jakých | ingrediencí jsi | ji | peklaI? |

| | | with which | ingredients be.2sg | it.acc | baked.ipfv.2sg.f |

| | Russian | | | | |

| | c. | Kakoj | vkusnyj | pirog | Marysia! |

| | | how | delicious | cake | Mary |

| | | Iz čego | ty | jego | pieklaI? |

| | | with what | you | it.acc | baked.ipfv.2sg.f |

| | | ‘What a delicious pie Mary. What ingredients did you bake it from?’ |

In (26), the object of the past creation event (a delicious pie) is available at the moment of speaking. In (26), the QUD is related to the object (the holder of the result state), and, more precisely, to the ingredients used to bake it. In (27), the object of the past event of building (the beautiful house) is available at the moment of speaking and the QUD is related to the initiator of the past event of building.

Strong resultative presuppositional factual context, focus on the initiator| | Polish | | | | |

| (27) | a. | Widzę, że | twój dom | jest | idealny. |

| | | see.1sg that | your house | is | ideal |

| | | Czy podasz | mi | namiar | na ekipę, |

| | | Q give.pres.pfv.2sg | me | contact | to crew |

| | | która | go | budowałaI? | |

| | | which | it.acc | built.ipfv.3sg.m | |

| | Czech | | | | |

| | b. | Vidím, že | tvůj dům | je | moc povedený. |

| | | see.1sg that | your house | is | ideal |

| | | Dáš | mi prosím | kontakt | na partu, |

| | | give.pres.pfv.2sg | me please | contact | to crew |

| | | která ho | stavělaI? | | |

| | | which it.acc | built.ipfv.3sg.f | | |

| | Russian | | | | |

| | c. | U tiebia | otličnyj | dom! | |

| | | by you | ideal | house | |

| | | Ty | možeš | dať | mnie |

| | | you | can | give | me |

| | | informaciju | o brigadie, | kotoraja | jego |

| | | information | about crew | which | it.acc |

| | | stroilaI? | | | |

| | | built.ipfv.3sg.f | | | |

| | | ‘I can see that your house is perfect. Can you give me the contact details of the team that built it? |

In weakly resultative presuppositional factual contexts, accomplishment verbs expressing a change-of-state of the object, but not leading to the existence of the object, were used, e.g., iron, repair, water, wash—as illustrated in (28) and (29).

weak resultative presuppositional factual context, focus on the result| | Polish | | | | |

| (28) | a. | Moja | koszulka | pięknie | pachnie |

| | | my | T-shirt | nicely | smells |

| | | po praniu. | | | |

| | | after washing | | | |

| | | Czy | możesz | mi powiedzieć, |

| | | Q | can.2sg | me tell |

| | | jakim | proszkiem | go prałaśI? |

| | | which.instr | powder.instr | it.acc washed.ipfv.2sg.f |

| | Czech | | | | |

| | b. | Moje | tričko | voní | pěkně |

| | | My | T-shirt | smells | nicely |

| | | po vyprání. | | | |

| | | after washing | | | |

| | | Můžeš | mi | říct, | |

| | | can.2sg | me | tell | |

| | | v jakém prášku | jsi | Ho pralaI. |

| | | in which powder | be.2sg | it.acc washed.ipfv.2sg.f |

| | Russian | | | | |

| | c. | Moja | futbolka | priekrasno | paꭓniet |

| | | my | T-shirt | nicely | smells |

| | | poslie stirki. | | | |

| | | after washing | | | |

| | | Podskaži, | kakim | poroškom ty |

| | | tell | which.instr | powder.instr you |

| | | jego.acc | stiralaI? | | |

| | | it.acc | washed.ipfv.2sg.f | | |

| | | ‘My shirt smells lovely after washing. Can you tell me what powder you washed it with.’ |

In (28), the object of the past event of washing, i.e., the nicely smelling T-shirt, is available at the moment of speaking. In (28), the QUD is related to the object (the holder of the result state), and, more precisely, to the washing powder used to wash the T-shirt.

weak resultative presuppositional factual context, focus on the initiator| | Polish | | | | |

| (29) | a. | Widzę, że | masz | w końcu | sprawny |

| | | see.1sg that | have.2sg | eventually | working |

| | | rower. | Ja | też | właśnie |

| | | bike | I | also | just |

| | | szukam | fachowców. | | |

| | | look_for.1sg | specialists | | |

| | | Czy | możesz | mi | powiedzieć, |

| | | Q | can.2sg | me | tell |

| | | kto | ci | go | naprawiałI? |

| | | who | you.dat | it.acc | repaired.ipfv.3sg.m |

| | Czech | | | | |

| | b. | Vidím, že | tvé | kolo je | nakonec |

| | | see.1sg that | your | bike is | eventually |

| | | funkční. | | | |

| | | working | | | |

| | | Právě | také | hledám | odborníky. |

| | | just | also | look_for.1sg | specialists |

| | | Můžeš | mi | říct, | kdo |

| | | can.2sg | me | tell | who |

| | | ti | ho | opravovalI. | |

| | | you.dat | it.acc | repaired.ipfv.3sg |

| | Russian | | | | |

| | c. | Ja vižu, | čto | tiebie | nakoniec-to |

| | | I see.1sg | that | you | eventually |

| | | počinili | vielosipied. | | |

| | | repaired | bike | | |

| | | Ja | tože | išču | mastiera. |

| | | I | too | look_for.1sg | specialist |

| | | Podskaži, | kto | tiebie | |

| | | tell | who | you.dat | |

| | | jego | činilI? | | |

| | | it.acc | repaired.ipfv.3sg | | |

| | | ‘Oh, you finally have a working bike. I am also looking for professionals. Can you tell me who repaired it for you.’ |

| | |

In (29), the object of the past event of repairing—that is the working bike—is available at the moment of speaking. However, the QUD is related to the initiator of the past event of repairing.

4.4. Predictions

Prediction 1

Based on

Dickey’s (

2000,

2015) micro-typology of aspect, in all of the tested contexts more choices of the imperfective are expected in Russian than in Czech and Polish, with Polish being transitional between Russian and Czech.

Prediction 2

More choices of the imperfective are expected in neutral existential factual contexts, exist-neut, than in the remaining conditions:

- -

exist-res

- -

srp-init

- -

srp-res

- -

wrp-init

- -

wrp-res

This is expected because the QUD in exist-neut contexts focuses on the adverb ever, which enforces the indefinite temporal location of the past event given that ever imposes a restriction that the event should happen at least once at some arbitrary (non-specific) temporal interval. Additionally, the rhetorical discourse structure remains neutral as to the relevance of the result state of this event for the current discussion. Additionally, these contexts refer to a past event that is possibly, but not necessarily, complete. This aspect of their meaning is underspecified, as it is not addressed in the QUD. All these factors make imperfective aspect strongly preferred. In the remaining conditions, QUDs are either related to the result of the past event or the past complex event is presupposed to exist, hence it is anchored to the timeline.

Prediction 3

More choices of the imperfective are expected in weak resultative presuppositional contexts than in strong resultative presuppositional contexts. The relevant planned comparisons are between:

wrp-init vs. srp-init

and

wrp-res vs. srp-res

This is expected because in weak resultative presuppositional contexts (with non-creation accomplishment verbs), the backgrounded past event might have consisted of a process sub-event that did not necessarily reach the result sub-event, thereby leading to more choices of imperfective aspect than in strong resultative presuppositional contexts with creation verbs.

Prediction 4

More choices of the imperfective are expected in presuppositional contexts focusing on the initiator than in the ones focusing on the result sub-event. The relevant planned comparisons are between:

srp-init vs. srp-res

and

wrp-init vs. wrp-res

This is motivated by the fact that in the contexts in which the existence of the past complex event is presupposed and the object (holder of the result state) is available at the moment of speaking—making the information that the past event reached the result state recoverable—the imperfective may be preferred when the QUD is related to the initiation sub-event than when it is related to the result subevent.

4.5. Results

In order to determine the presence of the differences in choice between imperfective (set as reference level) and perfective forms between the experimental conditions within and across Polish, Czech, and Russian, and to determine the existence of the overall difference between those languages, a general linear mixed effect model with binomial response using the

glmer function from the

lme4 (

Bates et al. 2015) package was fitted. The best model fit was obtained with participants and items set as random intercepts. The significance of the main effects of LANGUAGE and CONDITION and the interaction effect of LANGUAGE x CONDITION was based on the comparison of the model with no effects and main effects only, respectively. Pairwise comparisons using Z-tests, which were corrected with Holm’s sequential Bonferroni procedure, were obtained using the

glht function from the

multcomp package. A statistical analysis of aspect choices revealed a significant main effect for CONDITION (χ

2(5) = 41.6897;

p < 0.0001) and LANGUAGE (χ

2(2) = 6.6467;

p = 0.03603). However, no significant interaction effect between CONDITION and LANGUAGE was found (χ

2(10) = 14.8559;

p = 0.13740). Pairwise comparisons with respect to the main effect of CONDITION revealed significant differences between

exist-neut and other experimental conditions only.

exist-neut stimuli show a significantly greater probability of being completed with an imperfective form of the verb (rather than the perfective one) than stimuli in other experimental conditions. Pairwise comparisons with respect to the main effect of LANGUAGE revealed only marginally significant differences between Polish and Russian and Czech and Russian.

4.5.1. The Main Effect of LANGUAGE

A statistical analysis of aspect choices revealed a significant main effect for CONDITION (χ

2(5) = 41.6897;

p < 0.0001) and LANGUAGE (χ

2(2) = 6.6467;

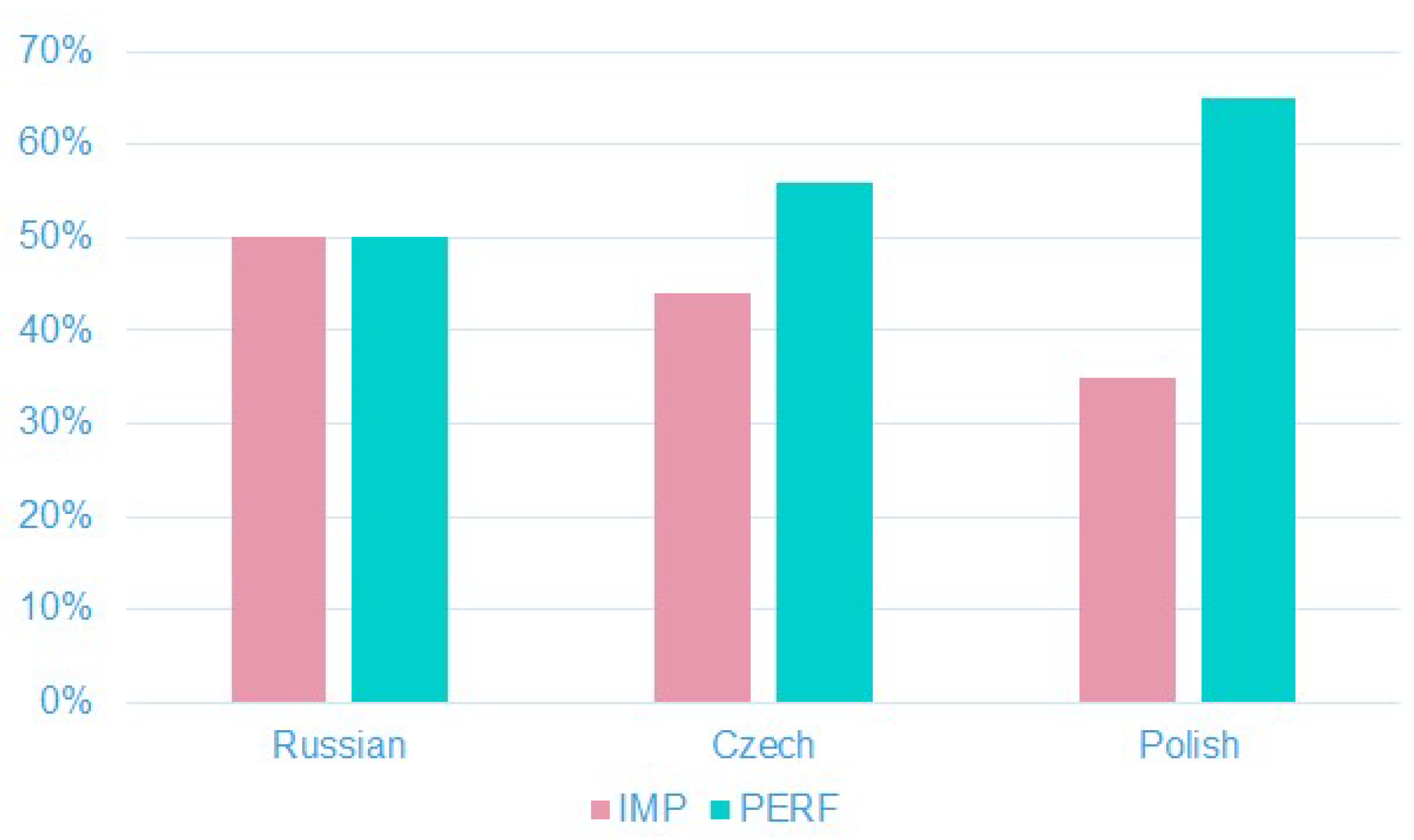

p = 0.03603). Pairwise comparisons with respect to the main effect of LANGUAGE revealed the following results (graphically represented in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5):

for the pairwise comparison between Polish and Czech, the estimated p-value = 0.6307

for the pairwise comparison between Polish and Russian, the estimated p-value = 0.0575 (significant)

for the pairwise comparison between Czech and Russian, the estimated p-value = 0.0692 (marginally significant)

4.5.2. The Main Effect of CONDITION

Pairwise comparisons with respect to the main effect of CONDITION revealed significant differences between

exist-neut and other experimental conditions (

p < 0.001), as shown in

Figure 6. Only

exist-neut stimuli showed a significantly greater probability of being completed with an imperfective form of the verb (rather than the perfective one) than stimuli in other experimental conditions.

4.5.3. Interaction between LANGUAGE and CONDITION

No significant interaction effect between CONDITION and LANGUAGE was found (χ

2(10) = 14.8559;

p = 0.13740), as shown in

Figure 7.

In

Figure 8, we additionally show the percentage of uses of imperfective and imperfective aspect in each condition in Russian, Polish, and Czech.

5. Discussion

Russian scored more uses of imperfective aspect in all the tested factual contexts than Czech and Polish (this effect was statistically marginally significant). The obtained result is in line with

Dickey’s (

2000,

2015) micro-typology of aspect in Slavic (partly confirming Prediction 1). However, Polish and Czech did not turn out to differ significantly, but, contrary to what

Dickey (

2000,

2015) proposed (but in line with

Mueller-Reichau 2018), it was not Polish that turned out to occupy an intermediate position between Russian and Czech, rather Czech turned out to be the intermediate between Russian and Polish (contrary to what was expected in Prediction 1).

In all the tested languages, there was a significantly higher proportion of imperfective usage in neutral existential contexts (in which the emphasis is put on the temporal indefiniteness of the past event and it is shifted away from its result state) as compared to all the remaining tested conditions (confirming Prediction 2). In resultative existential contexts, where the result state is causally related to earlier discourse, the rate of perfective choices increased significantly as compared to neutral existential contexts. Additionally, there is a visible trend towards a higher usage of imperfective in weakly resultative presuppositional contexts as compared to strongly resultative presuppositional contexts (though this difference did not reach significance). This trend is compatible with Prediction 4, but more items would have to be independently tested to confirm this prediction statistically. Prediction 3, under which more choices of the imperfective were expected in weak resultative presuppositional contexts (wrp-init and wrp-res) than in strong resultative presuppositional contexts (srp-init and srp-res), was not confirmed. This may be related to the fact that the contexts focusing on the result state in fact mentioned the means that led to obtaining the result. It is worth considering better ways of focusing on the result.

Even though it is not standard practice to interpret the results that are not statistically significant but only appear to form a trend, we think these trends may gain significance in further experiments using more focused designs with more collected data. This approach is additionally motivated by the fact that the tested phenomena are subtle and some factors we are not aware of may play an important role. One firm conclusion we should draw is that aspect choices in existential and presuppositional contexts should be addressed separately. Another important conclusion is that both discourse-level information and verb-level information affect aspect choices in general-factual contexts, and they do it differently in existential and presuppositional contexts. We will first address the results related to aspect choices in two types of existential contexts and then we will address aspect choices in four types of presuppositional contexts. We will relate the results to relevant aspects of the theories presented in

Section 2.

In neutral existential contexts with the adverb

ever and accomplishment verbs, Polish, Czech, and Russian show a clear preference for imperfective aspect (close to 100% choices). Why is imperfective aspect so strongly preferred in these contexts? As suggested by

Grønn (

2004), in existential factual imperfective contexts, imperfective is preferred in the absence of a temporal adverbial narrowly restricting the assertion time. For example, in existential factual imperfective contexts, imperfective occurs with an extended assertion time where the focus is on the existence of an event and the target state validity of telic predicates is irrelevant. By contrast,

Gehrke (

forthcoming b) argues that imperfective is preferred in existential factual contexts because the event is potentially iterative (refers to a plural set of events). Recall also that, according to

Mueller-Reichau (

2018), perfective has to do with event uniqueness. All these approaches seem to face a problem when confronted with the data from Russian presented in (30).

| (30) | Eto | byla | vešč | lučšaja | iz vsieꭓ | | | | |

| | it | was | thing | best | of all | | | | |

| | vieščej | kotoryje | ja | kogda-libo | sozdalP. | | | | |

| | things | which.3pl | I | ever | created.pfv.3sg.m | | | | |

| | ‘It was the best thing of all the things I had ever created.’ |

In (30), there is an extended assertion (reference) time and there is a plural event of

creating things (

kotoryje ‘which’ agrees in terms of person and number with the plural noun

vieščej ‘things’, and there is an implicature that the events of creating them happened on different occasions), but the perfective aspect is used contrary to what we could expect. What characterizes this context is that the plural set of objects (

vieščej ‘things’) in the domain of quantification of the universal quantifier

all is presupposed to exist. Consequently, the events of creating these objects as well as the temporal intervals to which they are anchored are also presupposed to exist in the past. As such, they can be anchored to specific past intervals. This suggests that the temporal specificity of the past event seems to be a facilitating factor in the choice of the perfective aspect in general-factual contexts in Russian. From this, we can draw a preliminary conclusion that backgrounded events are temporally specific (whether singular or plural) (see

Grønn 2015 for a similar view).

Additionally, we should keep in mind that imperfective co-varies with perfective in neutral existential contexts such as

exist-neut with the adverb

ever only in Polish and Czech. In Russian, imperfective is the only possible option in these contexts. Additionally, when achievement verbs such as

win or

lose are used in such contexts in Russian, imperfective is still the only option, while in Polish and Czech, perfective is obligatory (or at least strongly preferred)—as shown in (15), (16), and (17). In accounting for these observations, we rely on

Ramchand’s (

2008a) tense-aspect theory and her distinction between (in)definiteness at the macro- (second phase syntax) and micro-level (first phase syntax), where the former means the (in)definite temporal location with respect to the utterance time and the latter with respect to the temporal trace of an event. Temporal (in)definiteness at the macro-level should be understood in terms of temporal specificity (being anchored to a particular, non-arbitrary interval) on the timeline. Definiteness at the micro-level means that the time variable is situated at the transition point between the process sub-event and the result state in

Ramchand’s (

2008b) first phase syntax (leading to the choice of perfective forms during spell-out). Indefiniteness at the micro-level means that the time variable is situated as an arbitrary point within the temporal trace of an event (leading to the choice of imperfective during spell-out). We suggest that

exist-neut contexts are temporally indefinite at the macro-level and underspecified for definiteness (+/− definite) at the micro-level in the case of accomplishments. In

exist-neut, the result state of the past event is not relevant in the current conversation, hence nothing prevents the time variable from being placed at an arbitrary point relative to the temporal trace of an accomplishment event, thereby making imperfective aspect preferred in Polish, Czech, and Russian. Additionally, the temporal indefiniteness of the past event in

exist-neut is explicitly expressed by means of the adverb

ever stating that the past event could be potentially located at an arbitrary interval before the utterance time. Moreover, the QUD is directly related to the temporal indefiniteness of the past event with respect to the utterance time. This appears to significantly facilitate the placement of the time variable at an arbitrary point both with respect to the utterance time and within the temporal trace of an accomplishment event in Polish, Czech, and Russian. Why is imperfective obligatory in these contexts only in Russian? It appears to be the case that in Russian, when the QUD addresses the temporal indefiniteness of the past event, perfective is avoided, making imperfective obligatory. Russian perfective has to be anchored to a specific temporal location on the timeline, hence it is incompatible with contexts in which temporal indefiniteness is explicitly addressed. Why is perfective obligatory in Polish and Czech when achievement verbs are used in

exist-neut contexts? We would like to propose that in the case of achievements, the time variable is definite with respect to the temporal trace of an event. Achievements describe an instantaneous change-of-state, and the time variable can only be located at a unique time instant at which the change-of-state happens. This suggests that perfective in Polish and Czech (in contrast to Russian) does not require that the time variable is placed at a specific temporal location before the utterance time.

At this point, one can reasonably ask why perfective aspect can be used in exist-res contexts in Russian even though the temporal adverb today is rather vague as to the temporal location of the past event on the time axis. The QUD in Have you watered flowers today? asks whether the past event of watering flowers happened within the interval specified by the adverb today. Recall, however, that in exist-res contexts, the result state of the past event is causally related to earlier discourse. In this case, earlier discourse states that the flowers wilted. This implies that the QUD is whether the past event of watering happened before the flowers wilted. This makes the temporal location of the past event of watering flowers pragmatically specific, plus the result state of watering flowers is very relevant to the current discourse. This suggests that the temporal location of the past event is indefinite only at the sentence level, but that the surrounding discourse makes it pragmatically and temporally specific. This may explain why even in Russian, perfective aspect, which has to be anchored to a specific temporal location, is acceptable in this context. In fact, perfective aspect is preferred in exist-res in Russian, Polish, and Czech. This preference is stronger in Czech than in Russian and Polish. Why does perfective co-vary with imperfective in exist-res contexts? It appears to be the case that when the result state of the past event is relevant, as it is causally related to some event in earlier discourse, some speakers prefer to place a temporal variable at the transition point between the process sub-event and the result state (definiteness at the micro-level), leading to the choice of perfective aspect. However, some speakers may choose to place the time variable at an arbitrary point within the temporal trace of the past event when they consider sentential indefiniteness more relevant. The former option seems to be more likely in Czech and the latter option appears to be more frequent in Polish and Russian.

In presuppositional general-factual contexts, the presupposed events are temporally definite (specific) as they can be anchored to a particular interval on the timeline that is also presupposed to exist (the exact temporal location does not have to be specified). At the micro-level, the contexts with accomplishment predicates are underspecified (+/− definite) as to the location of the time variable with respect to the temporal trace of an event. The results of our study show a trend (which did not reach significance) indicating that, in the case of weakly resultative accomplishments with non-creation accomplishment verbs such as

iron and

water, the result state of the past event relates to some property of the object of this event, e.g., its being

watered or

ironed. Therefore, the fact that the object of the past event is available in the current conversation does not guarantee that the past event reached a result state. For this reason, speakers are more likely to place the time variable at an arbitrary point of the temporal trace of an event (definite), thereby facilitating the choice of imperfective. By contrast, in the case of a strongly resultative aspect (creation verbs), the existence of the object of the past event in the current discussion guarantees that the past complex event reached its result state, hence speakers are more likely to place the time variable at the transition between the process and result state sub-events (+ definite), thereby leading to a more frequent choice of perfective aspect. Based on that, we would like to suggest that the positioning of the time variable relative to the temporal trace of a complex past event depends on the interaction of discourse-level and verb-level information. Concerning the question why Russian makes more choices of imperfective aspect in presuppositional general-factual contexts than Polish and Czech (even though in all the three languages perfective is preferred), we would like to suggest a similar conclusion as

Altshuler (

2010,

2012), which supposes that perfective in Russian is more strongly associated with the Narration discourse relation, thereby making it less preferred in Elaboration contexts. This is also related to the fact that perfective in Russian “wants” to be anchored to a specific time interval and the Narration relation makes the temporal location of the past event very specific.

Altogether, we propose that in general-factual contexts, there is a competition between the choice of perfective and imperfective aspect and the ultimate choice depends on whether the speaker chooses to put more emphasis on the (in)definiteness of the temporal variable with respect to the temporal trace of a complex event or on the (in)definiteness (specificity) of the temporal variable with respect to the utterance time. In

Ramchand’s (

2008a) formalism, the spell-out domain is either vP or CP (see

Chomsky 2004,

2005a,

2005b). Since both types of (in)definiteness are made before CP (at the level of AspP and TP), the phonological realizations associated with them in the form of perfective and imperfective Vocabulary Items compete for insertion at the level of CP. The choice of the aspectual form may depend on very subtle nuances of context and on what kind of (in)definiteness is more relevant in a given scenario.

We also claim that Russian perfective is more strongly associated with temporal specificity (being anchorable to a specific interval on the time axis), as compared to Polish and Czech. Perfective cannot be used in contexts that explicitly state that the past event may have happened at an arbitrary moment in time. In contexts in which the past event is presupposed to exist, the interval to which it is anchored is also presupposed to exist (it is specific), hence perfective is not banned. The placement of the time variable with respect to the temporal trace of an event in the first phase syntax is determined by how relevant the result state is in the current conversation. When the result state is very relevant, the time variable is placed at the transition between the process sub-event and the result sub-event, leading to the choice of perfective aspect. Otherwise, it is placed at an arbitrary point within the temporal trace of an event, leading to the choice of imperfective aspect. Both discourse-level information and verb-level information may affect speakers’ choices as to whether the time variable should be positioned at the transition point or at an arbitrary point within the temporal trace of an event.