Visual and Artefactual Approaches in Engaging Teachers with Multilingualism: Creating DLCs in Pre-Service Teacher Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Multilingualism in Education

1.2. Arts-Based Approaches in Teacher Education

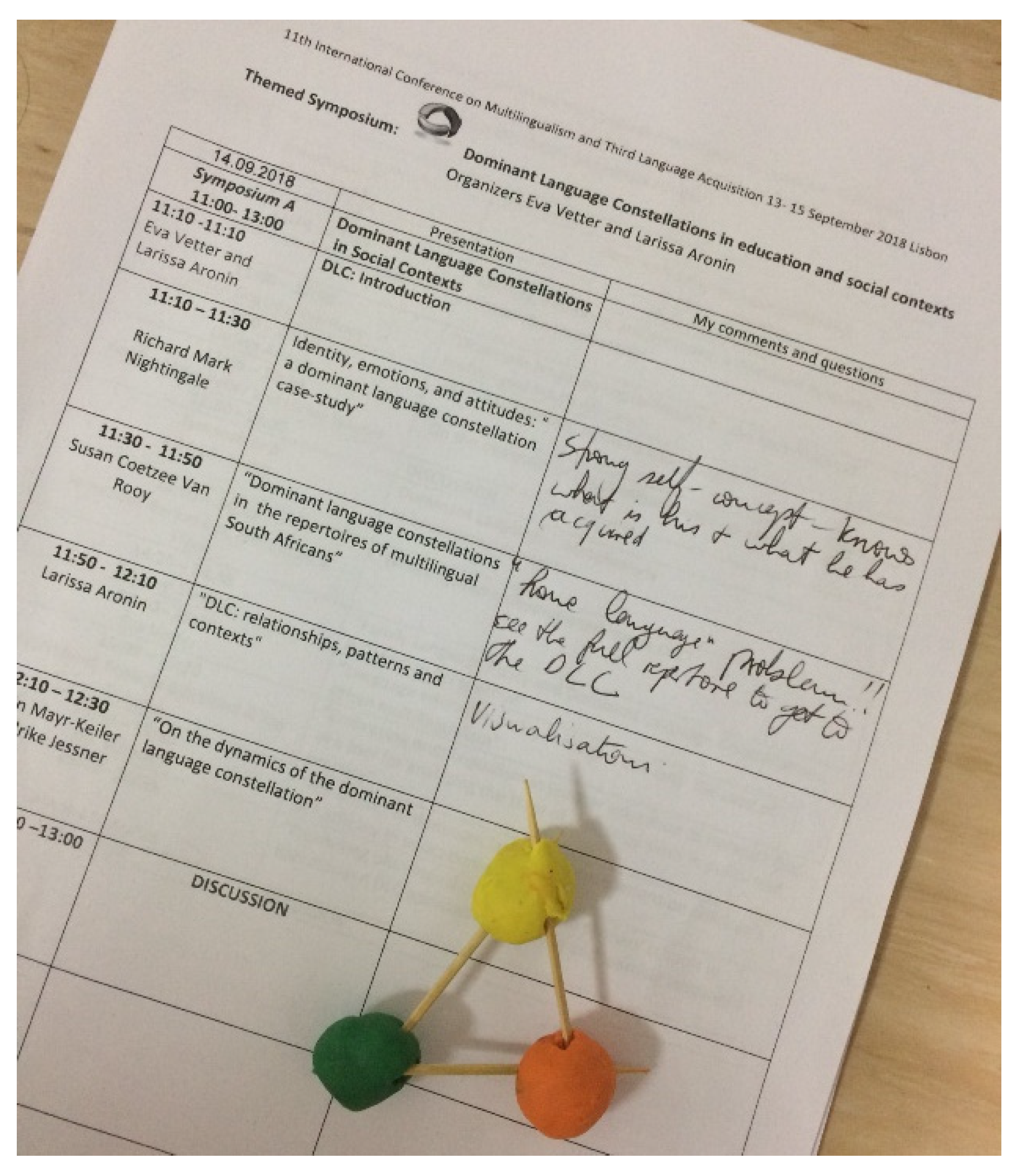

1.3. Dominant Language Constellations (DLCs) as a Research and Pedagogical Approach

1.4. DLC Maps and Modelling: Visual and Concrete Representations of Subjectively Lived Multilingualism

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim of the Study

- How did STs’ multimodal creations (artefacts and reflections) of DLC artefacts reveal a hidden multilingualism and a better understanding of their role as future teachers?

- How did STs’ choices in the creative process of making a DLC artefact contribute to exploring and representing subjectively lived multilingualism?

2.2. Context and Participants

- How did you organise your DLC and why did you choose this specific shape, materials, colours, etc… to represent your languages?

- How did creating a visual and manual (craft) representation of all your languages, in this specific shape, help you visualise your multilingualism and see yourself as a multilingual individual and multilingual teacher?

- How do you think this will change the way you approach your students’ other languages in your English lessons?

- How does this manual, visual, multimodal activity support and enhance creative teaching and ensure deep learning in the language classroom?

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Quantifying DLCs within Language Repertoires

2.4.1. Norwegian–English DLC

2.4.2. Scandinavian Languages

2.4.3. Foreign Languages

2.4.4. Future Language Learning

2.4.5. Personal Choice or Circumstances

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exploring the Artefact as Subjectively Lived Multilingualism

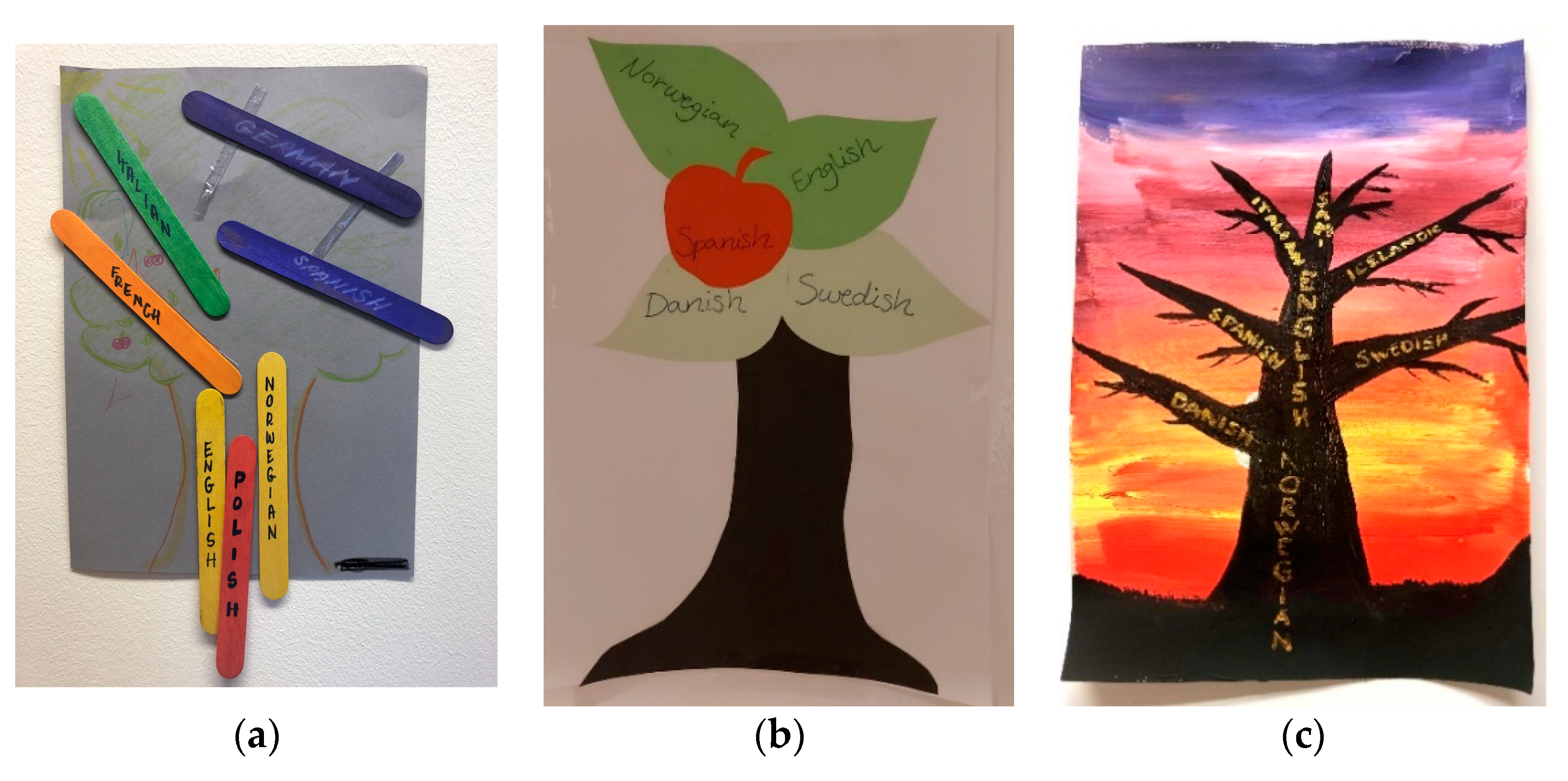

3.1.1. Personal and Symbolic Choices of DLC Artefacts: The Object Chosen

3.1.2. Personal and Symbolic Choices in the Creative Process: Shapes, Sizes, Colours, Layout

- People: Latvian–Since exchanging letters with my grandmother has always been in Latvian (and still is); Russian–Russian is associated with my father, who consciously encourages our written and spoken conversations to be in Russian; Polish–is represented as a heart because of the romantic connection I feel to the language, and the colours are bright as it is a language I use the most at home. In addition, the heart shape has been chosen to illustrate the connection to the Polish relatives on my mother’s side;

- Place: Norwegian–In addition to learning Norwegian at school, I learnt most of it at badminton trainings, where I could explore the dialect and talk in a more natural manner beyond the classroom;

- Experience: English–English is a language I started learning in the third grade. However, I mostly associate the language with pop-music, since I always looked up the lyrics and sang along to my favourite English songs. Therefore, English is represented with musical notation.

3.2. Engaging with the Multilingual Self and Implications for Classroom Practice

- Creating my DLC made me realise that I know more languages than I think I do. I have always thought that I only knew one language, Norwegian, but through the process of creating my DLC I realised that I do know more languages than I thought (ST11);

- From the DLC I learnt that I am multilingual (ST3);

- I think this made me acknowledge more languages, and that will help me visualise my multilingualism and see myself as a multilingual individual and multilingual teacher (ST5);

- By creating this atom to visualise my language repertoire I realised I know more than I thought I did. I was not aware that I knew 5 languages (ST14);

- By creating my own DLC I felt inspired by the linguistic story that this language map illustrates (ST2);

- The DLC helped me think of myself as a multilingual individual as it made me focus on my relationships with language (ST2);

- I have not seen myself as multilingual (ST7);

- I have already seen myself as a multilingual individual but creating the visual representation of all my languages made me even more sure about it (ST1).

- This assignment (and our recent sessions) have given me additional motivation to pursue multilingualism in my own classroom when I start teaching. (ST12);

- The activity invites pupils to express themselves visually and creatively, meaning that they could express feelings that are hard to describe in words. As an example, the pupils could create a DLC in their 8th grade and then edit it in their 10th Year to see if and how the interrelation between the languages has changed (ST13);

- As a teacher I want to acknowledge the different languages children have and maybe have them use it as a steppingstone to learn English and other languages (ST4);

- I can use this to help my students learn English by helping them see the connections and similarities between their own language and English (ST11);

- I would also try to learn a few words if it’s a language I don’t know so everyone feels included (ST3).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Interrelatedness of Language Repertoires and DLCs

The artefact is fixed, it represents the current situation, meaning that it would not display any changes if the correlation among the languages would switch. To exemplify, if I would like to teach German at some point, I would have to continue both development and practice of the language, meaning that at some moment the representation of German could become colourful, as well as brighter and bigger in size.

4.2. DLC Artefacts as Creative and Discursive Research and Pedagogical Tools

4.3. Visibilizing the Full Language Repertoire

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aronin, Larissa. 2006. Dominant Language Constellations: An approach to multilingualism studies. In Multilingualism in Educational Settings. Edited by Muiris Ó Laoire. Hohengehren: Schneider Verlag, pp. 140–59. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa. 2016. Multicompetence and Dominant Language Constellation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Multicompetence. Edited by Vivian Cook and Li Wei. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 142–63. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa. 2018. DLC: Relationships, Patterns and Contexts. Paper presented at the XIth International Conference on Third Language Acquisition and Multilingualism, Lisbon, Portugal, September 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa. 2019a. Lecture 1: What is multilingualism? In Twelve Lectures on Multilingualism. Edited by David Singleton and Larissa Aronin. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa. 2019b. Dominant Language Constellation as a method of research. In International Research on Multilingualism: Breaking with the Monolingual Perspective. Edited by Eva Vetter and Ulrike Jessner. Berlin: Springer, pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa. 2021. Dominant Language Constellations in education: Patterns and visualisations. In Dominant Language Constellations Approach in Education and Language Acquisition. Edited by Larissa Aronin and Eva Vetter. Cham: Springer, pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa, and David Singleton. 2008. Multilingualism as a New Linguistic Dispensation. International Journal of Multilingualism 5: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronin, Larissa, and David Singleton. 2012. Multilingualism. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa, and Eva Vetter, eds. 2021. Dominant Language Constellations Approach in Education and Language Acquisition. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa, and Laurent Moccozet. 2021. Dominant Language Constellations: Towards Online Computer-assisted Modelling. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronin, Larissa, and Muiris Ó Laoire. 2013. The Material Culture of Multilingualism: Moving beyond the Linguistic Landscape. International Journal of Multilingualism 10: 225–35. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhuizen, Gary, and Pat Strauss. 2020. Communicating Identities. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhuizen, Gary, Phil Benson, and Alice Chik. 2014. Narrative Inquiry in Language Teaching and Learning Research. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Björklund, Mikaela, and Siv Björklund. 2021. Embracing multilingualism in teaching practicum in Finland? DLC as a tool for uncovering individual and institutional multilingualism. In Dominant Language Constellations Approach in Education and Language Acquisition. Educational Linguistics. Edited by Larissa Aronin and Eva Vetter. Cham: Springer, pp. 131–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, David. 2014. Moving beyond ‘lingualism’: Multilingual embodiment and multimodality in SLA. In The Multilingual Turn. Edited by Stephen May. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 54–77. [Google Scholar]

- Blommaert, Jan, and Ad Backus. 2011. Repertoires Revisited: ‘Knowing Language’ in Superdiversity. Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies Paper 67: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Blommaert, Jan, and Ad Backus. 2013. Superdiverse repertoires and the individual. In Multilingualism and Multimodality: The Future of Education Research. Edited by Ingrid de Saint-Georges and Jean-Jacques Weber. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bristowe, Anthea, Marcelyn Oostendorp, and Christine Anthonissen. 2014. Language and Youth Identity in a Multilingual Setting: A Multimodal Repertoire Approach. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 32: 229–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burner, Tony, and Christian Carlsen. 2019. Teacher qualifications, perceptions and practices concerning multilingualism at a school for newly arrived students in Norway. International Journal of Multilingualism 19: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, Brigitte. 2018. The Language Portrait in Multilingualism Research: Theoretical and Methodological Considerations. In Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies Paper 236. London: King’s College London, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cenoz, Jasone, and Durk Gorter. 2011. A Holistic Approach to Multilingual Education: Introduction. The Modern Language Journal 95: 339–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone, and Durk Gorter, eds. 2015. Multilingual Education: Between Language Learning and Translanguaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee-Van Rooy, Susan. 2018. Dominant Language Constellations in Multilingual Repertoires: Implications for Language-in-Education Policy and Practices in South Africa. Language Matters 49: 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 2020. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment Companion Volume. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, Available online: www.coe.int/lang-cefr (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Edwards, John R. 1994. Multilingualism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2014. Perusopetuksen Opetussuunnitelman Perusteet [National Core Curriculum for Basic Education]. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Fisher, Linda, Michael Evans, Karen Forbes, Angela Gayton, and Yongcan Liu. 2020. Participative Multilingual Identity Construction in the Languages Classroom: A Multi-theoretical Conceptualization. International Journal of Multilingualism 17: 448–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García, Ofeila, and Tatyana Kleyn. 2019. Teacher Education for Multilingual Education. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Edited by Carol A. Chapelle. Oxford: Blackwell/Wiley Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 2010. Bilingual: Life and Reality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haukås, Åsta. 2016. Teachers’ Beliefs about Multilingualism and a Multilingual Pedagogical Approach. International Journal of Multilingualism 13: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henry, Alistair. 2017. L2 Motivation and Multilingual Identities. The Modern Language Journal 101: 548–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsu, Lavinia, Sally Zacharias, and Dobrochna Futro. 2021. Translingual Arts-based Practices for Language Learners. ELT Journal 75: 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Nayr. 2014. Perceptions of identity in trilingual 5-year-old twins in diverse pre-primary educational contexts. In Early Years Second Language Education: International Perspectives on Theories and Practice. Edited by Sandie Mourão and Mónica Lourenço. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Nayr. 2019. Children’s multimodal visual narratives as possible sites of identity performance. In Visualising Multilingual Lives: More Than Words. Edited by Paula Kalaja and Sílvia Melo-Pfeiffer. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Nayr. 2021. Artefactual narratives of multilingual children: Methodological and ethical considerations in researching children. In Ethical and Methodological Issues in Researching Young Language Learners in School Contexts. Edited by Annamaria Pinter and Harry K. Kuchah. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 126–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Nayr. 2022. Mainstreaming multilingualism in education: An Eight-D’s framework. In Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Teaching Foreign Languages in Multilingual Settings. Edited by Anna Krulatz, Georgios Neokleous and Anne Dahl. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Nayr. forthcoming. Educating teachers multilingually. In Innovative Practices in Early English Language Education. Edited by David Valente and Daniel Xerri. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ibrahim, Nayr, and Marina Prilutskaya. 2021. Indigenous perspectives in English Language Teaching (ELT): How a North Sami and Norwegian dual-language picturebook created opportunities for teaching English interculturally and multilingually. Blog for Department of English Webpage at Nord University. July 25. Available online: https://blogg.nord.no/englishatnord/news-and-events/indigenous-perspectives-in-elt/ (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Jessner, Ulrike. 2013. Complexity in multilingual systems. In The Encyclopaedia of Applied Linguistics. Edited by Carol A. Chapelle. New York: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaja, Paula, and Anne Pitkänen-Huhta. 2018. Visual Methods in Applied Language Studies. Double Special Issue. Applied Linguistics Review 9: 157–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalaja, Paula, and Anne Pitkänen-Huhta. 2020. Raising Awareness of Multilingualism as Lived–in the Context of Teaching English as a Foreign Language. Language and Intercultural Communication 20: 340–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaja, Paula, and Sílvia Melo-Pfeifer, eds. 2019. Visualising Multilingual Lives: More Than Words. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick, Maureen, and Roberta McKay. 2002. Uncovering Literacy Narratives through Children’s Drawings. Canadian Journal of Education 27: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kendrick, Maureen, and Roberta McKay. 2009. Researching literacy with young children’s drawings. In Making Meaning: Constructing Multimodal Perspectives of Language, Literacy, and Learning through Arts-Based Early Childhood Education. Edited by Marilyn J. Narey. New York: Springer, pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 2002. Colour as a Semiotic Mode: Notes for a Grammar of Colour. Visual Communication 1: 343–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krulatz, Anna, and Anne Dahl. 2016. Baseline Assessment of Norwegian EFL Teacher Preparedness to Work with Multilingual Students. Journal of Linguistics and Language Teaching 7: 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Krulatz, Anna, and Anne Dahl. 2021. Educational and career opportunities for refugee-background adults in Norway: A DLC perspective. In Dominant Language Constellations Approach in Education and Language Acquisition. Educational Linguistics. Edited by Larissa Aronin and Eva Vetter. Cham: Springer, pp. 109–28. [Google Scholar]

- Krulatz, Anna, and Yaqiong Xu. 2021. Forging Paths Towards the Multilingual Turn in Norway: Teachers’ Beliefs, Experience and Identity. Paper presented at MoMM (Multilingualism on My Mind) Conference, Bergen, Norway, March 18. [Google Scholar]

- Lähteelä, Johanna, Juli-Anna Aerila, and Merja Kauppinen. 2021. Art as a path to language–art-based language learning and the development of language awareness. In A Map and Compass for Innovative Language Education: Steps Towards Development. Edited by Josephine Moate, Anu Palojärvi, Tea Kangasvieri and Liisa Lempel. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, pp. 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, Elizabeth. 2020. Urban multilingualism and family language policy. In Urban Multilingualism in Europe: Bridging the Gap between Language Policies and Language Practices. Edited by Giuditta Caliendo, Rudi Janssens, Stef Slembrouck and Piet Van Avermaet. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 121–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Bianco, Joseph. 2020. A meeting of concepts and praxis: Multilingualism, language policy and the dominant language constellation. In Dominant Language Constellations: A New Perspective on Multilingualism. Edited by Joseph Lo Bianco and Larissa Aronin. Cham: Springer, pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Bianco, Joseph, and Larissa Aronin, eds. 2020. Dominant Language Constellations: A New Perspective on Multilingualism. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, Eliane, Anna Krulatz, and Eivind Nessa Torgersen. 2021. Embracing linguistic and cultural diversity in multilingual EAL classrooms: The impact of professional development on teacher beliefs and practice. Teaching and Teacher Education 105: 103428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, Richard. 2020. A Dominant Language Constellations case study on language use and the affective domain. In Dominant Language Constellations. Educational Linguistics. Edited by Joseph Lo Bianco and Larissa Aronin. Cham: Springer, pp. 231–59. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training. 2020. Læreplan i engelsk. Available online: https://www.udir.no/lk20/eng01-04?lang=eng (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Orland-Barak, Lily, and Ditza Maskit. 2017. Visuals as ‘illustrations’ of experience’. In Methodologies of Mediation in Professional Learning: Professional Learning and Development in Schools and Higher Education. Edited by Lily Orland-Barak and Ditza Maskit. Cham: Springer, pp. 137–49. [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowska, Agnieszka. 2014. Does Multilingualism Influence Plurilingual Awareness of Polish Teachers of English? International Journal of Multilingualism 11: 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otwinowska, Agnieszka. 2017. English Teachers’ Language Awareness: Away with the Monolingual Bias? Language Awareness 26: 304–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Ruth, ed. 2010. New Perspectives on Narrative and Multimodality. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, Ana Sofia. 2019. Plurilingual education and the identity development of pre-service English language teachers: An illustrative example. In Visualising Multilingual Lives: More Than Words. Edited by Paula Kalaja and Sílvia Melo-Pfeifer. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 214–31. [Google Scholar]

- Portolés, Laura, and Otilia Martí. 2020. Teachers’ Beliefs about Multilingual Pedagogies and the Role of Initial Training. International Journal of Multilingualism 17: 248–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pran, Kristin R., and Linn S. Holst. 2015. Rom for Språk: Rapport [A Survey on Multilingual Perceptions and Competencies in Norwegian Schools]. Oslo: The Norwegian Language Council. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, Cathy K. 2007. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Norway. 2021. Immigrants and Norwegian-Born to Immigrant Parents. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/innvbef (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Tabaro Soares, Camila, Joana Duarte, and Mirjam Günther-van der Meij. 2021. ‘Red Is the Colour of the Heart’: Making Young Children’s Multilingualism Visible through Language Portraits. Language and Education 35: 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, Eva. 2021. Language education policy through a DLC lens: The case of urban multilingualism. In Dominant Language Constellations Approach in Education and Language Acquisition. Educational Linguistics. Edited by Larissa Aronin and Eva Vetter. Cham: Springer, pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Vikøy, Aasne, and Åsta Haukås. 2021. Norwegian L1 Teachers’ Beliefs about a Multilingual Approach in Increasingly Diverse Classrooms. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Li. 2018. Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language. Applied Linguistics 39: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, Li. 2020. Dialogue/Response—Engaging translanguaging pedagogies in higher education. In Plurilingual Pedagogies: Critical and Creative Endeavors for Equitable Language in Education. Edited by Sunny M. C. Lau and Saskia van Viegen. Cham: Springer, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw, Jessica. 2019. Arts-Based Teaching and Learning in the Literacy Classroom: Cultivating a Critical Aesthetic Practice. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yoel, Judith. 2021. The Dominant Language Constellations of immigrant teacher trainees in Israel: Russian, Hebrew and English. In Dominant Language Constellations Approach in Education and Language Acquisition. Educational Linguistics. Edited by Larissa Aronin and Eva Vetter. Cham: Springer, pp. 151–69. [Google Scholar]

| Student Teacher | Language Repertoire | DLC | Artefact/Object | 2D/3D | Materials Used | Presentation of Languages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST1 | Polish, Norwegian, English, Spanish, French, German, Italian | Norwegian–English–Polish | Tree and foliage | 2D | Coloured card, ice-cream sticks, pencil crayons, paint | Written in English on the ice-cream sticks |

| ST2 | Norwegian, English Swedish, Danish, Spanish | Norwegian–English | Apple tree | 2D | Coloured card | Written in English on the leaves and apple |

| ST3 | Norwegian, English Danish, Swedish, Icelandic, Italian, Sami | Norwegian–English | Tree and branches | 2D | Coloured card, paint | Written in English on the trunk and branches of the tree |

| ST4 | Norwegian, English Swedish, Danish, Spanish | Norwegian–English | Mobile: butterflies | 3D | Pleated paper with printed flags, string | Represented by flags |

| ST5 | Norwegian, English Swedish, Danish German, French | Norwegian–English | Mobile: circles and hearts | 3D | Coloured card, string | Written in English on the card |

| ST6 | Norwegian, English Swedish, German, Danish | Norwegian–English–Swedish | Hearts: cut-out hearts on card | 2D | Coloured card | Written in English on hearts |

| ST7 | Norwegian, English Danish, Swedish, German | Norwegian–English | Hearts: origami nested hearts | 3D | Coloured card | Written in English on outside of hearts |

| ST8 | Latvian, Russian, German, English, Norwegian | Norwegian–English–Latvian | Hearts: heart and paper garlands | 3D | Coloured card, paper | Written in original language and script |

| ST9 | Norwegian, English, Swedish, Spanish, German, ASL | Norwegian–English | Sky and clouds | 2D | White card, colour felt-tip pens | Written in English on clouds |

| ST10 | Norwegian, English, Ukrainian, Russian, French | Ukrainian–Norwegian–English | Planets | 2D | Coloured card | Written in English on planets |

| ST11 | Norwegian, English Swedish, Danish, German | Norwegian–English | Matches | 2D | Matches, white paper, colour pencils | Written in English above flames |

| ST12 | Norwegian, English Chinese, German, Dutch | Norwegian–English | Book | 3D | Cardboard, paper, felt-tip pens | Designated by flags, objects with a sentence or word written in original language |

| ST13 | Latvian, Russian, English, Norwegian, Polish, German, Latin | Latvian–English–Norwegian–Polish | Globe | 2D and 3D | White and coloured paper, colour pencils, plastic | Designated by flags, places of learning, languages in English and original script |

| ST14 | Norwegian, English, Swedish, Dutch, Danish | Norwegian–English | Atom | 3D | Coloured card, string | Written in English |

| Language | Number of Times Language Is Mentioned |

|---|---|

| Norwegian | 14 |

| English | 14 |

| Swedish | 9 |

| Danish | 9 |

| German | 9 |

| Spanish | 4 |

| French | 3 |

| Russian | 3 |

| Dutch | 2 |

| Italian | 2 |

| Latvian | 2 |

| Polish | 2 |

| Ukrainian | 1 |

| Sami | 1 |

| Chinese | 1 |

| Icelandic | 1 |

| Latin | 1 |

| ASL | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibrahim, N.C. Visual and Artefactual Approaches in Engaging Teachers with Multilingualism: Creating DLCs in Pre-Service Teacher Education. Languages 2022, 7, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020152

Ibrahim NC. Visual and Artefactual Approaches in Engaging Teachers with Multilingualism: Creating DLCs in Pre-Service Teacher Education. Languages. 2022; 7(2):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020152

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbrahim, Nayr Correia. 2022. "Visual and Artefactual Approaches in Engaging Teachers with Multilingualism: Creating DLCs in Pre-Service Teacher Education" Languages 7, no. 2: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020152

APA StyleIbrahim, N. C. (2022). Visual and Artefactual Approaches in Engaging Teachers with Multilingualism: Creating DLCs in Pre-Service Teacher Education. Languages, 7(2), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020152