How and When to Sign “Hey!” Socialization into Grammar in Z, a 1st Generation Family Sign Language from Mexico

Abstract

:1. The Language(s)

2. Emergence, Complexity, and Bimodality

3. A Grammaticalization Chain in Z

4. Victor’s Acquisition of HEY

4.1. The Corpus and the Annotations

4.2. Vic at about 1 Year of Age: Communicative Intentions, Pointing?

5. Vic’s Apparent Conventional Z COME Sign at 16 Months

6. Vic’s Development of HEY1 for Attentional Control

7. The Development of HEY2 and Emancipation from Attention

8. Final Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Other younger children were later born into the signing household, but their developing language repertoires are not considered in this article. The notion of “generation” is vexed in such a genealogy. The terminological distinction between “generation” and “cohort” applied (for example, in Coppola 2020b) to the evolution of Nicaraguan Sign Language is complicated in Z by Rita, the hearing daughter of one of Jane’s hearing older sisters, who is thus genealogically the start of a 2nd generation, but who nonetheless grew up as (by five years) the youngest of a small cohort of household children, including all the deaf siblings, who were already signing when she was born. |

| 2 | The author has been a fictive kinsman and close friend of the deaf children’s parents since they were first married in the late 1960s. He was probably the first to realize that Jane was deaf, although sadly—out of ignorance—insufficiently perspicacious at the time to help her parents facilitate a different sort of linguistic development for her, for example, via appropriate deaf schooling, something not readily available in rural Mexico and of no interest then, or now, to the parents themselves. The author’s work on Z was in turn directly inspired by the research of Carol Padden and her co-authors on ABSL (e.g., Sandler et al. 2005; Aronoff et al. 2008), a village sign language of the Negev with somewhat similar origins, having also begun with a cohort of deaf siblings. |

| 3 | See the sketchy but fascinating early reference to a family homesign in Frishberg (1975, p. 713 fn. 13). Aside from classic studies of individual homesigners—deaf children born to hearing parents who receive little or no early exposure to sign languages—most famously by Susan Goldin-Meadow and her colleagues (e.g., Goldin-Meadow and Feldman 1977; Feldman et al. 1978; Goldin-Meadow et al. 1994; Goldin-Meadow 2003, 2012), there is comparative material on adult Brazilian homesigners in the work of Ivani Fusellier-Souza (e.g., Fusellier-Souza 2004, 2006; Martinod et al. 2020), as well as extensive work on Nicaraguan homesigners (e.g., Hunsicker and Goldin-Meadow 2012, 2013; Coppola 2020a; Flaherty et al. 2021). |

| 4 | For grammaticalization in general, see Heine (1997); Hopper and Traugott (1993). Overviews of grammaticalization processes in sign languages are in Pfau and Steinbach (2006, 2011), and Janzen (2012). For proposed grammaticalization paths in emerging sign languages linking speakers’ gestures to signed lexemes, see, for example, Perniss and Zeshan (2008), De Vos (2012b), and, for a village sign language in another Mayan context, Le Guen (2012). |

| 5 | Kata Kolok, a Balinese village sign language, is reported by De Vos (2012a, p. 186) to have “[a] form of COME that is produced with repeated movement and directed at a person to summon an addressee. This function is linked to Balinese co-speech gesture, in which an identical gesture has been observed”. There is no evidence that the Z HEY1 sign has a relationship to “come” either as a gesture or as Z sign itself (Haviland 2015), and as Austin German (p.c.) points out to me, other sign languages have very similar signs in both form and function. |

| 6 | In connection with the reduced pragmatic or semantic function of the Z sign HEY2, introduced below, note that the spoken Tzotzil k-al-tik av-aɁi expression also has a heavily abbreviated and similarly grammaticalized form vaɁi ‘listen’ or “pay attention (to what I’m about to say or do)”, which often introduces new topics in discourse or even such a non-verbal act as passing over a coin to pay for something. The initial v- in this form is a reduction of the second person ergative proclitic, and the underlying Tzotzil root aɁi, sometimes glossed as ‘hear’, is more accurately translated as ‘perceive’, regardless of sensory modality. |

| 7 | This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grants BCS-0935407 and BCS-1053089, administered by the Center for Research on Language [CRL] at UCSD. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation |

| 8 | Initial annotation of the corpus was conducted by the author or by Austin German (see German 2018). We have not tried to control systematically for the differences in Vic’s linguistic practices across different categories of interlocutors, hearing and deaf. |

| 9 | See Haviland (2020a, pp. 47–51) for a more detailed treatment of this small interaction. |

| 10 | This short scene is treated in more detail in Haviland (2020a, pp. 51–54). |

| 11 | A reviewer asks whether Tzotzil-speaking infants in families without deaf members use visual and tactile gestures for getting attention, and not surprisingly, they do, abundantly (see Haviland 2000; De León Pasquel 2005). They also grab or manipulate clothing, hair, and bodyparts—even faces—to attract caregivers. |

| 12 | To be fair to Vic, in that context he was unable to summon anyone’s attention with his gesture, as his mother was busy describing an eliciting stimulus to Rita and Terry, and they ignored him. Vic had been eating a banana and had been trying to get them to notice it. In any case, he did not follow up, returning to his banana and soon being distracted elsewhere. However, it seems clear that Vic can acquire some aspects of a Z sign without mastering the entire gestalt of appropriate usage (see De Vos 2012b). |

| 13 | Because previously secured attention is the criterion for glossing a sign such as HEY2 in my transcriptions, there can sometimes be doubt about individual instances when the video record leaves unclear or ambiguous where an interlocutor is gazing, as is the case in Figure 23. |

| 14 | During this period, because of his grandparents’ fears, the little boy was sent to live with his hearing aunt who ran a small vegetable shop in the nearby Mexican town, for days at a time rarely interacting with his deaf mother and uncles and exposed continuously to spoken Tzotzil and some Spanish. The grandparents only relented after several months before Vic was allowed to alternate between living in the village with his mother and spending time with his aunt in town. |

| 15 | Viewing this scene eleven years after it was filmed, Rita and Terry were unsure whether to read this sign as HEY2 or to interpret it as COME, which here would be a directive for Jane to get out of bed. If that was what it was, it failed, because what Jane did instead was flop back down on the bed and ignore Vic entirely. |

| 16 | I thank Austin German for suggesting that a summary table be included, although I doubt he will thank me for the lengthiness of the result. |

References

- Aronoff, Mark, Irit Meir, Carol A. Padden, and Wendy Sandler. 2008. The roots of linguistic organization in a new language. Interaction Studies 9: 133–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brentari, Diane, and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2017. Language emergence. Annual Review of Linguistics 3: 363–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carrigan, Emily M., and Marie Coppola. 2017. Successful communication does not drive language development: Evidence from adult homesign. Cognition 158: 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Herbert H. 1996. Using Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, Marie. 2020a. Gestures, homesign, sign language: Cultural and social factors driving lexical conventionalization. In Emerging Sign Languages of the Americas. Edited by Olivier Le Guen, Josefina Safar and Marie Coppola. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 349–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, Marie. 2020b. Sociolinguistic sketch: Nicaraguan Sign Language and homesign systems in Nicaragua. In Emerging Sign Languages of the Americas. Edited by Olivier Le Guen, Josefina Safar and Marie Coppola. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 438–50. [Google Scholar]

- De León Pasquel, Lourdes. 2005. La Llegada del Alma: Lenguaje, Infancia y Socialización Entre los Mayas de Zinacantán. Mexico City: CIESAS. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, Connie. 2012a. Sign-Spatiality in Kata Kolok. Ph.D. dissertation, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, Connie. 2012b. The Kata Kolok perfective in child signing: Coordination of manual and non-manual components. In Sign Languages in Village Communities: Anthropological and Linguistic Insights. Edited by Ulrike Zeshan and Connie De Vos. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 127–52. [Google Scholar]

- Duranti, Alessandro, Elinor Ochs, and Bambi Schieffelin, eds. 2012. The Handbook of Language Socialization. Malden: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Heidi, Susan Goldin-Meadow, and Lila Gleitman. 1978. Beyond Herodotus: The creation of language by linguistically deprived deaf children. In Action, Symbol, and Gesture: The Emergence of Language. Edited by Andrew Lock. New York: Academic Press, pp. 351–414. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, Molly, Dea Hunsicker, and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2021. Structural biases that children bring to language learning: A cross-cultural look at gestural input to homesign. Cognition 211: 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frishberg, Nancy. 1975. Arbitrariness and iconicity: Historical change in American Sign Language. Language 51: 696–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusellier-Souza, Ivani. 2004. Sémiogenèse des Langues des Signes, Étude de Langues des Signes Emergentes (LS ÉMG) Pratiquées par des Sourds Brésiliens. Doctoral thesis, Sciences du Langage, Université Paris 8, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Fusellier-Souza, Ivani. 2006. Emergence and development of sign languages: From a semiogenetic point of view. Sign Language Studies 7: 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, Austin. 2018. Constructing Space in Zinacantec Family Homesign. BA Honors thesis, Department of Linguistics, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan, and Dianne Brentari. 2017. Gesture, sign, and language: The coming of age of sign language and gesture studies. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 40: E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan, and Heidi Feldman. 1977. The development of language-like communication without a language model. Science 197: 401–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan, Cynthia Butcher, Carolyn Mylander, and Mark Dodge. 1994. Nouns and Verbs in A Self-Styled Gesture System: What’s in A Name? Cognitive Psychology 27: 259–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan. 2003. The Resilience of Language: What Gesture Creation in Deaf Children Can Tell Us about How All Children Learn Language. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan. 2012. Homesign: Gesture to language. In Sign Language. An International Handbook. Edited by Roland Pfau, Marcus Steinbach and Bencie Woll. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 601–25. [Google Scholar]

- Green, E. Mara. 2021. The eye and the other: Language and ethics in deaf Nepal. American Anthropologist 124: 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, John B. 2000. Early pointing gestures in Zinacantán. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 8: 162–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haviland, John B. 2011. Nouns, verbs, and constituents in an emerging ‘Tzotzil’ sign language. In Representing Language: Essays in Honor of Judith Aissen. Edited by Sandra Chung, William Ladusaw, James McCloskey, Rodrígo Gutiérrez-Bravo, Line Mikkelsen and Eric Potsdam. Santa Cruz: California Digital Library eScholarship Repository, Linguistic Research Center, University of California, Santa Cruz, pp. 151–71. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, John B. 2013a. (Mis)understanding and obtuseness: Ethnolinguistic borders in a miniscule speech community. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 23: 160–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haviland, John B. 2013b. The emerging grammar of nouns in a first generation sign language: Specification, iconicity, and syntax. Gesture 13: 309–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haviland, John B. 2013c. Xi to vi: Over that way, look! (Meta)spatial representation in an emerging (Mayan?) sign language. In Space in Language and Linguistics. Edited by Peter Auer, Martin Hilpert, Anja Stukenbrock and Benedikt Szmerecsanyi. Berlin and Boston: Walter De Gruyter, pp. 334–400. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, John B. 2014. Different strokes: Gesture phrases and gesture units in a family homesign from Chiapas, Mexico. In From Gesture in Conversation to Visible Action as Utterance. Edited by Mandana Seyfeddinipur and Marianne Gulberg. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 245–88. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, John B. 2015. Hey! Topics in Cognitive Science 7: 124–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, John B. 2016. But you said ‘four sheep’.!: (sign) language, ideology, and self (esteem) across generations in a Mayan family. Language and Communication 46: 62–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haviland, John B. 2019. Grammaticalizing the face (as well as the hands) in a first generation sign language: The case of Zinacantec Family Homesign. In Papers from the ICHL22. Edited by Michela Cennamo and Claudia Fabrizio. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 521–62. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, John B. 2020a. Signs, interaction, coordination, and gaze: Interactive foundations of Z—an emerging (sign) language from Chiapas, Mexico. In Emerging Sign Languages of the Americas. Edited by Olivier LeGuen, Josefina Safar and Marie Coppola. Berlin: DeGruyter, Ishara Press, pp. 35–96. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, John B. 2020b. Zinacantec Family homesign (or Z). In Emerging Sign Languages of the Americas. Edited by Olivier LeGuen, Josefina Safar and Marie Coppola. Berlin: DeGruyter, Ishara Press, pp. 293–400. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, Berndt. 1997. Possession: Cognitive Sources, Forces, and Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, Gabrielle, Lindsay N. Ferrara, and Benjamin D. Anible. 2019. The semiotic diversity of doing reference in a deaf signed language. Journal of Pragmatics 143: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holler, Judith, Kobin H. Kendrick, Marisa Casillas, and Stephen C. Levinson. 2006. Turn-Taking in Human Communicative Interaction. Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul J., and Elizabeth C. Traugott. 1993. Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Lynn, and Connie de Vos. 2021. Classifications and typologies: Labeling sign languages and signing communties. Journal of Sociolinguistics 26: 118–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsicker, Dea, and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2012. Hierarchical structure in a self-created communication system: Building nominal constituents in homesign. Language 88: 732–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunsicker, Dea, and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2013. How handshape type can distinguish between nouns and verbs in homesign. Gesture 13: 354–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janzen, Terry. 2012. Lexicalization and grammaticalization. In Sign Language: An International Handbook. Edited by Roland Pfau, Markus Steinbach and Bencie Woll. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 816–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kendon, Adam. 2004. Gesture, Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Le Guen, Olivier. 2012. An exploration in the domain of time: From Yucatec Maya time gestures to Yucatec Maya Sign Language time signs. In Endangered Sign Languages in Village Communities: Anthropological and Linguistic Insights. Edited by Ulrike Zeshan and Connie de Vos. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter and Ishara Press, pp. 209–50. [Google Scholar]

- Le Guen, Olivier, Marie Coppola, and Josefina Safar. 2020. Introduction: How Emerging Sign Languages in the Americas contributes to the study of linguistics and (emerging) sign languages. In Emerging Sign Languages of the Americas. Edited by Olivier Le Guen, Josefina Safar and Marie Coppola. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, Stephen C. 2006. On the human interaction engine. In Roots of Human Sociality. Edited by Nicholas J. Enfield and Stephen C. Levinson. New York: Routledge, pp. 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lutzenberger, Hannah, Roland Pfau, and Connie de Vos. 2022. Emergence or Grammaticalization? The Case of Negation in Kata Kolok. Languages 7: 23. [Google Scholar]

- Martinod, Emmanuella, Brigitte Garcia, and Ivani Fusellier. 2020. A typological perspective on the meaningful handshapes in the emerging sign languages on Marajó Island (Brazil). In Emerging Sign Languages of the Americas. Edited by Olivier LeGuen, Josefina Safar and Marie Coppola. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 203–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mesh, Kate, and Lynn Hou. 2018. Negation in San Juan Quiahije Chatino Sign Language. Gesture. John Benjamins Publishing Company 17: 330–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2018. Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction 51: 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondada, Lorenza, Sofian Bouaouina, Laurent Camus, Guillaume Gauthier, Hanna Svensson, and Burak Tekin. 2021. The local and filmed accountability of sensorial practices. The intersubjectivity of touch as an interactional achievement. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 4: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, Elinor, and Bambi Schieffelin. 1984. Language acquisition and socialization: Three developmental stories. In Culture Theory: Mind, Self, and Emotion. Edited by Richard Shweder and Robert LeVine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs, Elinor, and Bambi Schieffelin. 2012. The theory of language socialization. In The Handbook of Language Socialization. Edited by Alessandro Duranti, Elinor Ochs and Bambi B. Schieffelin. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Perniss, Pamela, and Ulrike Zeshan. 2008. Possessive and existential constructions in Kata Kolok (Bali). In Possessive and Existential Constructions in Sign Languages. Edited by Ulrike Zeshan and Pamela Perniss. Nijmegen: Ishara Press, pp. 125–50. [Google Scholar]

- Petitto, Laura Ann, Marina Katerelos, Bronna G. Levy, Kristine Gauna, Karine Tétreault, and Vittoria Ferraro. 2001. Bilingual signed and spoken language acquisition from birth: Implications for the mechanisms underlying early bilingual language acquisition. Journal of Child Language 28: 453–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pfau, Roland, and Marcus Steinbach. 2006. Modality-independent and modality-specific aspects of grammaticalization in sign Languages. Linguistics in Potsdam 24: 5–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pfau, Roland, and Marcus Steinbach. 2011. Grammaticalization in sign languages. In The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization. Edited by Heiko Narrog and Bernd Heine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 683–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pfau, Roland. 2015. The grammaticalization of headshakes: From head movement to negative head. In New Directions in Grammaticalization Research. Edited by Andrew D. M. Smith, Graeme Trousdale and Richard Waltereit. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 9–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, Harvey, Emmanuel Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50: 696–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sacks, Harvey. 1987. On the Preferences for Agreement and Contiguity in Sequences in Conversation. In Talk and Social Organization. Edited by Graham Button and John R. E. Lee. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 54–69. First published 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, Wendy, Irit Meir, Carol Padden, and Mark Aronoff. 2005. The emergence of a grammar: Systematic structure in a new language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102: 2661–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schegloff, Emmanuel A. 1970. Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist 70: 1075–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schegloff, Emmanuel A. 1998. Body torque. Social Research 65: 535–96. [Google Scholar]

- Yngve, Victor H. 1970. On getting a word in edgewise. In Chicago Linguistics Society, 6th Meeting. Edited by M. A. Campbell. Chicago: University of Chicago, pp. 567–78. [Google Scholar]

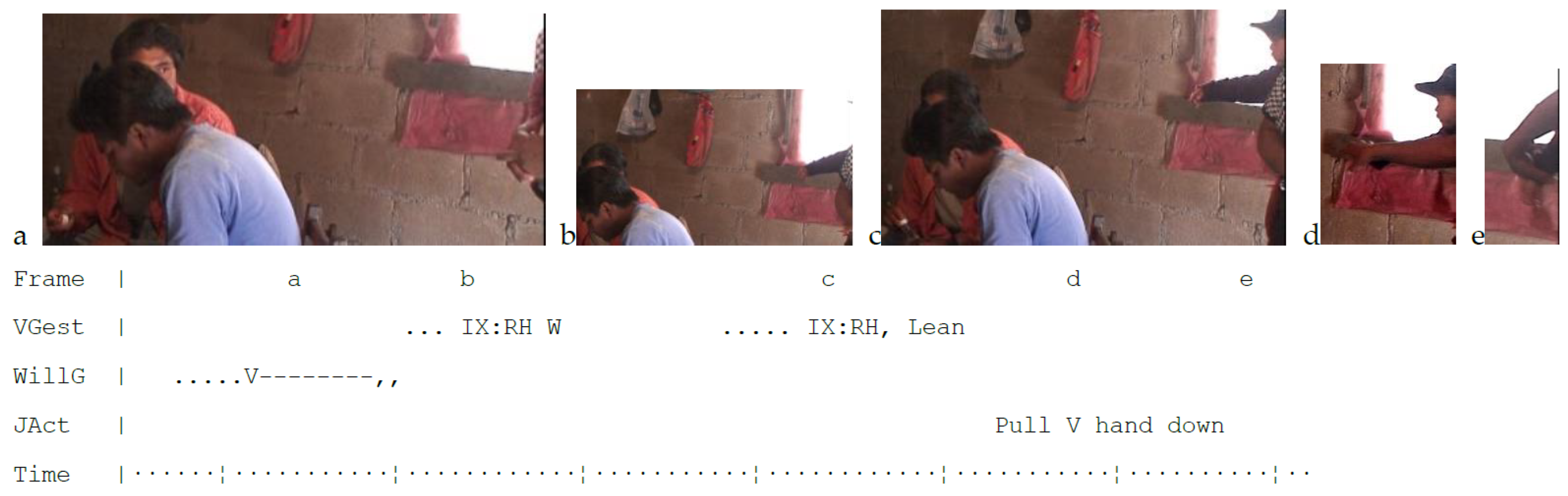

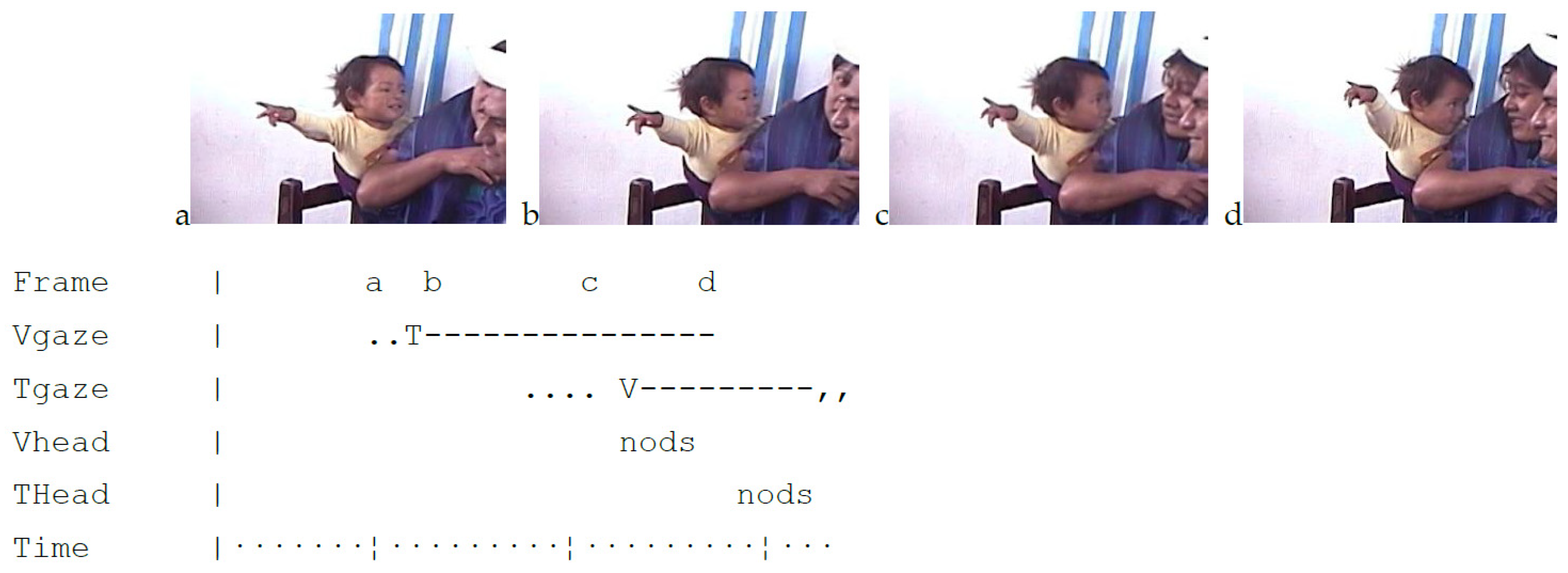

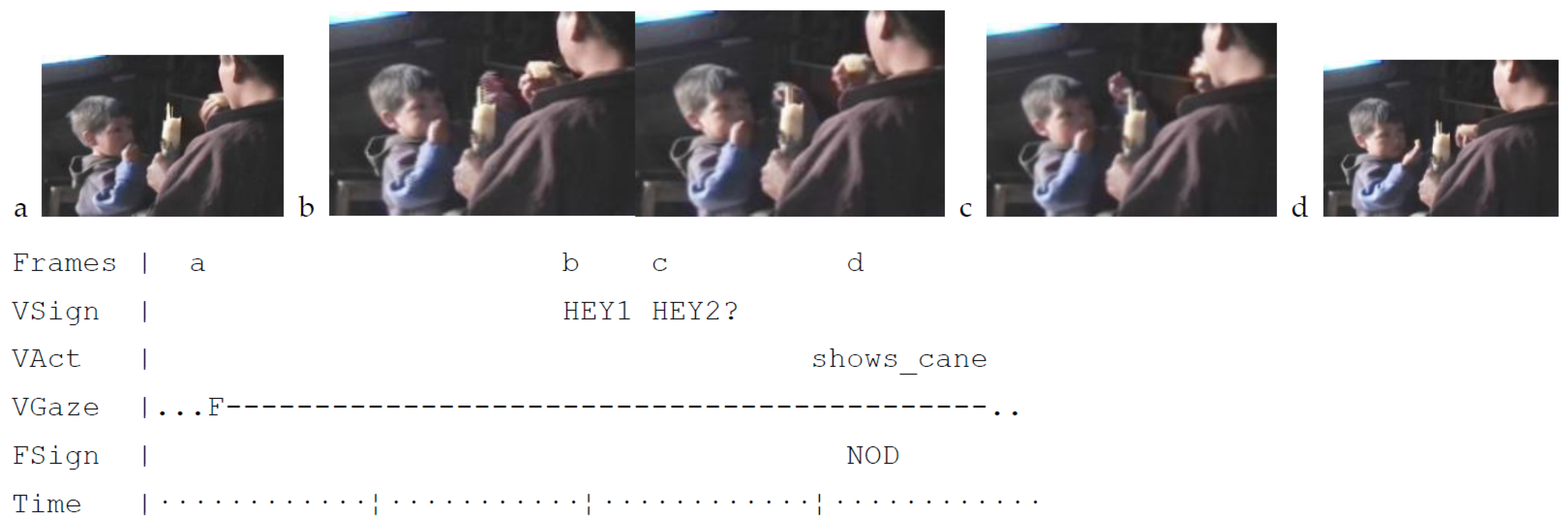

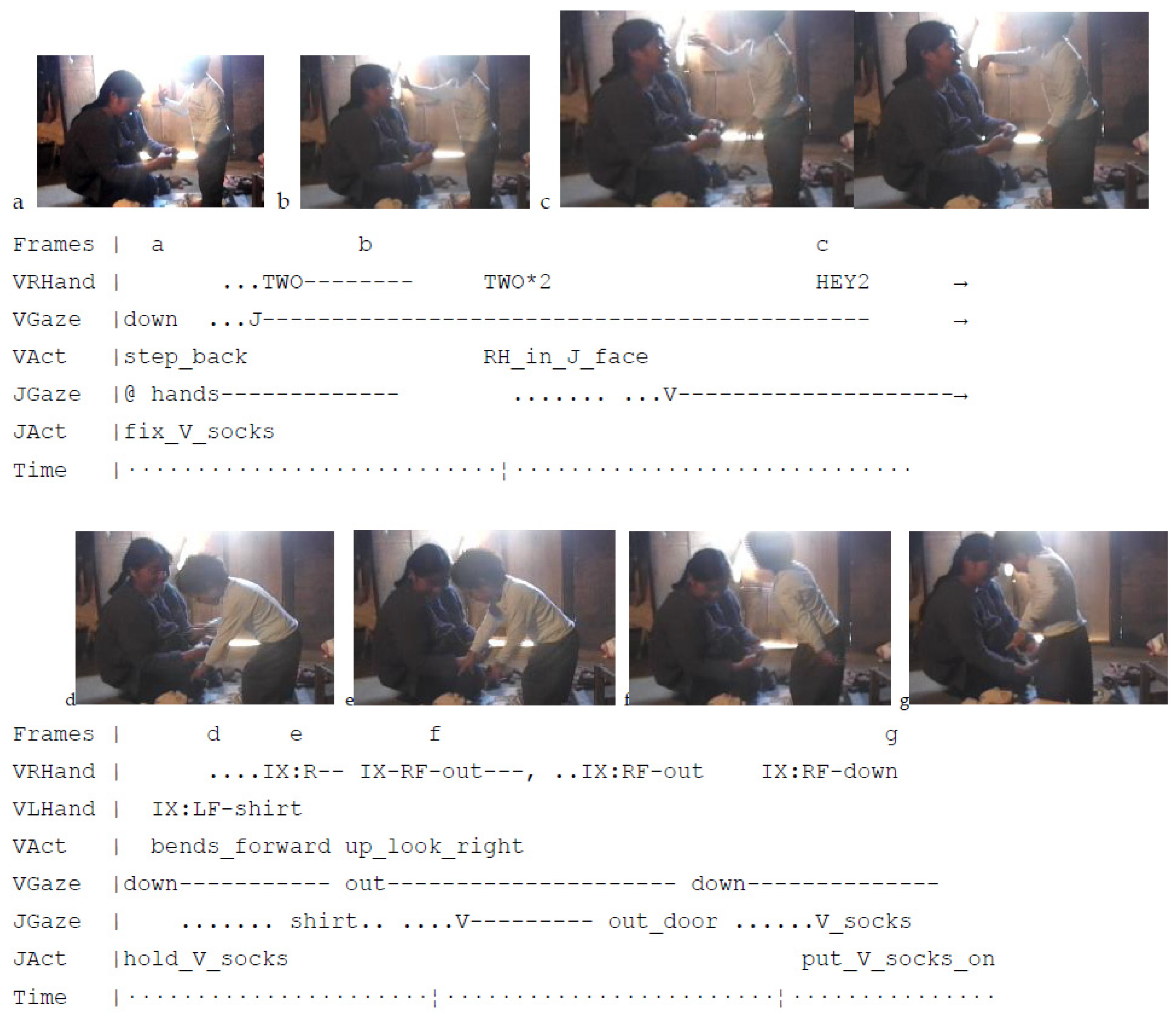

| Frame | Letters show the position of each labeled illustrative still frame with respect to the full timeline | ||

| Time | Shows subdivided timeline in the form |. . . . . . . . .| | Vertical bar (|) marks each second | Individual dots (.) subdivide each second into equal subunits |

| Label for each tier | XY | X is a participant initial | Y is a type: Gaze, Gest(ure), Sign, Act(ion) |

| Ballistics | ….. | Preparatory excursion | |

| ! | Stroke of a gesture | ||

| ---- | Hold | ||

| ,,,, | Retraction | ||

| Abbreviations in glosses | IX:y z | Indexical sign, with y as articulator | |

| z = putative referent | |||

| RH | Right hand | ||

| LF, RF | Left, or right (index) finger |

| Putative “Stages” | Months | Figures | Developing Stages |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Pointing, gaze, touch without signs | 11 | Figure 6 | Vic is aware of the gaze of others (and it may prompt him to try to initiate interaction). He also uses pointing as a proto directive and expects a reaction. However, he has no “control” over his expressive use of either gaze or gesture and almost no formal mechanisms for achieving attention (except, perhaps, reaching/pointing). His mother already communicates a kind of metapragmatic “suppression” of some of his actions. |

| Ia. Limited gestural attention management. | 12 | Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 | Explicit devices for achieving attention: (mutual) gaze, touch, and voice, synchronized with gaze. In Figure 8, Vic adjusts to and acknowledges mutual attention, coordinating gaze with head movements and touch, as well as more pointing (Figure 9). There is also the first hint of developing gestural morphology: an index finger point leads to a tiny proto-wave (Figure 10 and Figure 11), although Vic’s attention remains focused on referents and only laterally moves to potential interlocutors. Nonetheless, Vic seems to start to recruit manual signals for managing attention. |

| II. Conventional signs, directives | 16 | Figure 12 | Vic has acquired a robust set of conventional Z signs, including COME, which stands as a silent Z directive, appropriately addressed via prior gaze but with no attentional device other than the sign itself. |

| IIb. HEY as unmoored request for attention | 17 | Figure 14 | Vic appears to try to use a sign similar to COME to request a (hearing) interlocutor’s attention. It is not yet clear whether he intends the sign to be a preamble to some specific follow-up action. He still resorts to tactile and indexical gestures to request attention from deaf interlocutors (Figure 15). |

| IIc. HEY in combination with other modalities | 18 | Figure 16 | In interaction with the deaf adults, Vic uses a variety of manual devices to try to control attention, including versions of what looks clearly like HEY, sometimes coalescing with indexical pointing directives, and beginning to coordinate his gaze with the candidate interlocutors. |

| 22 | Figure 17 | Vic was even more actively trying to manage the interlocutors’ attention, but perhaps because he lacked status to do so by a HEY sign, he resorted to other means to coerce the others’ gaze—grabbing people’s faces or clothes (Figure 18). | |

| IId. Interactive and sequential links between HEY and following utterance | 24 | Figure 20 | Vic’s turn to his mother suggests a growing metalinguistic connection between the HEY1 sign and an immediately following utterance. |

| 25–27 | Figure 21 | Vic’s contributions to conversational exchanges begin to be closely coordinated with his achieving prior visual attention from the target of HEY1 signs. This is plainly true in conversation with his uncles, who often disattend his attempts to sign, but also true on occasion with his normally doting mother (Figure 22). | |

| III. HEY2 as probable separable sign | 27 | Figure 23 and Figure 24 | Although filmed evidence often fails to demonstrate that Vic has already secured his interlocutor’s gaze, aspects of the conversational structure suggests that Vic has begun to distinguish HEY2 by using the latter to highlight and introduce a specific signed utterance. |

| IIIa. Articulatory and functional emancipation of HEY2 from attention request. | 28 | Figure 25 | By using one hand to sign what appears to be HEY2 and the other hand almost simultaneously to sign a substantive utterance, Vic demonstrates a close synchronic link between the pragmatic sign HEY2 and the forthcoming conversational turn which it pre-visages. |

| 34 | Figure 26 | Vic makes no request for attention, but when he gets it, he issues HEY2 before making a substantive turn. | |

| 35 | Figure 27 | Vic is engaged in intensive interaction with a single interlocutor, but when he achieves a mutual gaze, he uses HEY2 to start to introduce a new topic. | |

| IIIb. Adult-like use of HEY2 | 41+ | Figure 28 and Figure 29 | Vic’s use of HEY2 seems to be fully adult, introducing a new turn or an explicit topic change. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haviland, J.B. How and When to Sign “Hey!” Socialization into Grammar in Z, a 1st Generation Family Sign Language from Mexico. Languages 2022, 7, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020080

Haviland JB. How and When to Sign “Hey!” Socialization into Grammar in Z, a 1st Generation Family Sign Language from Mexico. Languages. 2022; 7(2):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020080

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaviland, John B. 2022. "How and When to Sign “Hey!” Socialization into Grammar in Z, a 1st Generation Family Sign Language from Mexico" Languages 7, no. 2: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020080

APA StyleHaviland, J. B. (2022). How and When to Sign “Hey!” Socialization into Grammar in Z, a 1st Generation Family Sign Language from Mexico. Languages, 7(2), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020080