1. Introduction

Text annotation is writing, drawing, or other inscriptions made on the surface of a page, and serves a range of purposes. It can record one’s reaction to the page contents (in the case of a reader); respond to both the original contents and previous readers’ reactions (in the case of successive readers of the same physical text); and indicate suggested ways of engaging with the contents of the page (in the case of an author, a publisher, or an instructor) (

Antia 2017;

Miles 1997;

Roby 1999). A historical account is beyond the scope of this discussion, but antecedents of annotations in Western, African, and Eastern traditions can be gleaned from, respectively, the medieval traditions of exegesis, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the colophone in Chinese calligraphy (

Dorman and Hellmuth 2021;

Liu 2006;

Wolfe and Neuwirth 2001).

Annotations may be present in text as so-called ‘null-content’ (e.g., highlights, underlines, circling, arrow lines to link related ideas) or with a ‘body’ (word gloss, simplification of a construction, summary, exemplification, guiding questions, critical comment—all of which can be in the same language as the original text, in a different language, or even in a blend of languages) (

Antia and Mafofo 2021). Punctuation marks, asterisks, strikethroughs, doodles, drawings, and voice recordings are all ways in which texts may be annotated. However they present, annotations have been associated with a range of functions, including: improving the comprehension of the source materials; interpreting and commenting upon the text; facilitating reflective thinking; recording affective responses to text; calling attention to topics and important passages for future use. In the case of successive readers of the same physical text, the functions include eavesdropping on the reactions of other readers, especially expert readers, for clues of important points, controversial points, etc.; and facilitating conversation (

Antia and Mafofo 2021;

Wolfe and Neuwirth 2001;

Wolfe 2000).

As a means of interacting with text and/or image on the surface of a page, annotations are literacy practices that are not uncommon in the experience of university students (

Antia and Mafofo 2021;

Ben-Yehudah and Eshet-Alkalai 2014;

Liu 2006;

Lo et al. 2013), even though some students may not annotate at all. It is not a skill that can be taken for granted, and, in fact, academic literacy centres and similar student support structures at several universities and colleges provide resources on annotations

1. Of course, students can be expected to annotate differently depending on such factors as the reading material and the purpose of the reading. This caveat is consistent with a social practices approach to literacy that recognises the social, ideological, contextual, and other determinants of literacy practices (

Baynham 1995;

Prinsloo and Baynham 2013;

Street 2005). In annotating material that they read for their studies, students have been observed to underline and to highlight, to write and to draw, to translate and to simplify, to summarise and to critique, to use signs conventionally and non-conventionally, to be cryptic or apparent, and to engage with and to disengage from text, among others (

Antia and Mafofo 2021).

Likened to John-Steiner’s ‘jottings of the mind’ (

Antia and Mafofo 2021), annotations have enormous but, as yet, largely untapped potential as heuristic for the study of cognitive processes in reading. Annotations have, in other words, not widely been studied for what they reveal about what students attend to in text, what languages and/or other semiotic resources they draw upon in engaging with text, their problem-solving strategies, the level at which they are engaging with text, and, importantly, how the foregoing provide a basis for teachers to intervene to validate, reinforce, correct, or teach reading skills and practices valued generally or prized within specific disciplines. If it is correct to argue that “[r]eviewing a student’s annotated text conveniently offers a window through which a teacher may discern a learner’s thinking styles and find effective ways to facilitate each learner’s critical thinking process” (

Liu 2006, p. 194), then the practice of diagnostic assessment is undoubtedly all the poorer for this limited engagement with student annotations. Diagnostic assessment seeks “to determine a learner’s strengths and areas of improvement in the skills and processes being targeted in assessment and instruction, and to use that information to (…) improve the student’s learning and to guide further instruction” (

Jang and Wagner 2013, p. 691). Thus, annotations have only been infrequently used as a basis for such aspects of disciplinary reading pedagogy as reinforcing certain reading practices, drawing attention to unhelpful practices, and, more generally, enhancing the quality of feedback.

Against this backdrop, this article draws on text annotations obtained from teacher trainee students (n = 7) enrolled at a German university to examine what different students attend to while reading and their problem-solving strategies, as well as the role of language and other semiotic systems in the process, their level of engagement with the text, and how these insights can be leveraged for assessing and providing feedback on content reading. The study is framed theoretically by the notion of text movability (

Hallesson and Visén 2018;

Liberg et al. 2011).

2. Literature Review

It is currently difficult to imagine a higher education system in which engaging with text in some form or other could be dispensed with. Students are “exposed to a number of texts and textbooks that require independent reading” and which they “are expected to comprehend […] so that they can analyse, critique, evaluate and synthesise information from various sources” (

Bharuthram 2012, p. 205). Indeed, being a student requires one to demonstrate the competencies necessary to “identify and track points and claims being made in texts (…); understand and evaluate the evidence that is used to support claims made by writers of texts; extrapolate and draw inferences and conclusions from what is stated or given in text; understand vocabulary, including vocabulary related to academic study, in their contexts” (

NBT Team/CETAP 2018, p. 4).

Most conceptualizations of reading include bottom-up and interactive processes (

Bernhardt 1983;

Rumelhart 1985;

Smith 2012). Reading is central to the subject discipline: readers need to extrapolate meaning from texts with complex information presented in concise language (

Yapp et al. 2021). Students have to be able to grasp concepts of a scholarly field, and they have to be able to critically engage with these concepts in order to participate in discussions in academic contexts. Evaluating concepts or ideas necessitates background knowledge, and, of course, linguistic knowledge (

Di Tommaso 2015). While the level of familiarity with the language of an academic text is no doubt a factor in how easily a student processes such a text, academic literacy skills of inferring and evaluating meaning also rely on an ability to intertextually link meaning in a current text to meanings in previous texts.

In an increasing number of German higher education contexts, academic reading takes place in a foreign-language medium, specifically English (

Schroedler 2020). In fact,

Gürtler and Kronwald (

2015) have calculated an increase of 1300% in English-medium instruction (EMI) courses in the decade before 2015. EMI programmes are implemented in order to contribute to plurilingualism and pluriculturalism in modern German society (

Knapp and Schumann 2008), to enhance internationalization (

Hu 2016,

Schroedler 2020), or for economic reasons of student employability in global markets (

Gürtler and Kronwald 2015). Moreover, German scholars are increasingly obliged to publish internationally, mostly in English-speaking outlets, in order to advance their career. With research and teaching being interdependent, these international publications are then assigned to students for course reading.

However, critical voices have been raised concerning the dominance of English in the German higher education landscape because such dominance cements the hegemonic position of English even more, to the detriment of genuine multilingualism (

Schroedler 2020). At any rate, the implication of the current situation is that domestic and international students in German higher education are increasingly having to read academic texts in English. Of course, the foregoing is not intended to suggest that domestic students do not have difficulty processing academic texts in their German L1 reading. There is no gainsaying that academic reading is a practice that needs to be explicitly taught. Consequently, teachers are—perhaps unfairly—entrusted with this task, irrespective of the subject matter and the peculiar disciplinary ways of meaning-making. It has, in fact, been observed that subject content instructors lack knowledge of how to incorporate elements of reading literacy into their content teaching (

LeVan and King 2017).

There clearly is a sense in which the notions of diagnostic assessment and annotations are together able to generate some of the insights required for unlocking students’ reading and for empowering both academic development instructors and content-course instructors. Some insight into directions in which annotations support several interrelated goals of reading instruction can in fact be gleaned from the burgeoning literature on annotation and reading. An often incidental, and sometimes major, goal of reading is to unlock the organisation or macro/microstructures of a text. As has been suggested, “[t]he recognition of an organizational pattern enables the student to form a mental representation of the information and to see the logical relationships advanced by the author” (

Lo et al. 2013, p. 415). The ways in which annotations have been used to map (and make visible) text organisation have been described (e.g., by

Jensen and Scharff 2014 who use the term ‘outlining’), and the effects have been investigated in areas such as attention management and memorisation (

Antia and Mafofo 2021), cued and free recall of text content (

Lo et al. 2013), etc. The evidence points to annotation having a positive impact on memory and orientation within text.

The relationship between annotating and inference drawing from text has also been investigated, for instance, by

Ben-Yehudah and Eshet-Alkalai (

2014) in a study of undergraduate students in Israel who had to read under four conditions grouped in a 2 × 2 design (print condition with or without annotation; digital condition with or without annotation). The researchers found that annotations had a positive effect on inference-level questions in the print condition only, and had no impact on factual level questions in either medium. The role of annotation in supporting critical reading alone, or, in addition, how critical reading then translates into critical writing, has also been studied (e.g.,

Jensen and Scharff 2014;

Liu 2006), with one study finding that “skillful annotators produced more critical and analytical writing samples than did verbatim annotators. Verbatim annotators recycled information rather than analyzing it” (

Liu 2006, p. 205).

Given these affordances of text annotation for what is frequently described generically as enhanced comprehension—affordances that clearly also index metacognition—diagnostic assessment commends itself as a framework through which both students and instructors can attempt to understand and improve disciplinary reading.

Following

Jang and Wagner (

2013, p. 691), we understand diagnostic assessment as seeking to determine areas of strength in a learner’s demonstration of a particular skill or ability, and areas of some concern, and then using this information to improve learning and to “guide further instruction”. In a similar vein, but focusing on language,

Lee (

2015, p. 303) defines diagnostic assessment to be “the processes of identifying test takers’ (or learners’) weaknesses, as well as their strengths, in a targeted domain of linguistic and communicative competence and providing specific diagnostic feedback and guidance for (remedial) learning”. Drawing on research by

Alderson (

2005),

Alderson et al. (

2014),

Davies (

1968), and

Kunnan and Jang (

2011),

Lee (

2015) identifies the essential characteristics of diagnostic language assessment as implicitly conceptualising goals to work toward on the basis of the learners’ current level of proficiency and an identification of the learners’ potential on the basis of the learners’ current strengths and weaknesses. This requires a multicomponential view of the competence to be developed. Diagnostic assessment is turned both towards the past in terms of past learner performance and the future, and it demands an increased attendance to feedback. Therefore, diagnosis, diagnostic feedback, and remedial learning are seen as the core components of diagnostic assessment (

Lee 2015, p. 308). In this way, diagnostic assessment contributes to the alignment of learning, teaching, and assessment (

Vogt and Rossa 2021). Several types of diagnostic assessment can be identified depending on who is engaged with scrutinising the learners’ performance. Besides teacher-led diagnostic assessment, peers can also co-operate in identifying the learner’s strengths and weaknesses and in jointly formulating future learning goals on that basis; students can be taught to evaluate their own progress (sensu strengths and weaknesses) and to use this insight for identifying learning goals to work toward.

The assessment of reading is usually not concerned with annotations. Although

Alderson (

2000) contends that there is no one “best method” for testing reading (p. 203), multiple choice formats, cloze tests, and gap-filling tests are most commonly used to gauge reading comprehension. Matching, ordering tasks, and dichotomous items are classified as alternative techniques (p. 215ff.), or, likewise, alternative integrated approaches such as C-tests, short answer tests, free recall tests, or summary tests. Cognitive processes during academic reading have been explored in language testing environments, e.g., by

Bax (

2013), who investigated test takers’ cognitive processing on a reading test component, based on

Khalifa and Weir’s (

2009) model of reading and using eye-tracking technology.

In summary, then, a strong rationale for the current exploratory study is that, both within the German higher education system in which students increasingly have to read in a so-called L2 English and internationally, there is a relative dearth of scholarship around how annotations might support a set of interrelated goals: providing (proxy) data on students’ reading processes; analysing these processes against certain benchmarks (e.g., disciplinary expectations); and serving as a basis for offering feedback that is empirically supported. Through these goals, potentially, the students’ (metacognition of their) reading is enhanced, as is the ability of content instructors to incorporate elements of reading instruction into their teaching.

In turning to text movability in the next section, we seek to establish the theoretical foundations for the proposal to use annotations as a window into, and a diagnostic tool for, students’ reading.

3. Text Movability as a Theoretical Framework to Annotations

The notion of text movability describes, simultaneously, how students read or relate to texts and how they “express their understanding” (

Liberg et al. 2011, p. 79; see also

Hallesson and Visén 2018). It is typically operationalised as text-talks in which students respond to questions about their reading and from which a determination is made of how they have been reading. The notion builds on the idea of levels of reading, specifically on

Langer’s (

2011) account of ‘envisionment’ moves, that is, how readers build a mental textworld. In a first move, readers step into a text and get acquainted with it superficially. In a second move, the text is processed at a deeper level. The third move sees the reader stepping out of the text to relate its contents to external experiences. In a fourth move, the reader reflects critically on the contents read.

Liberg and colleagues (

Liberg et al. 2011) propose three forms of text movability, viz. text-based movability (expressing engagement with both superficial features and inferential, as well as critical dimensions of text); associative movability (linking text to personal experience); and interactive movability (demonstrating an understanding of the purpose and audience of the text). Although it is considered to be a hallmark of mature academic literacy to be able to demonstrate all forms, it may not always be possible to have them all instantiated in one text, and one cannot also lose sight of a range of factors that determine which form is demonstrated and how (e.g., whether a text is part of a major course or an elective, a student’s reading practices, etc.).

Our operationalisation of movability in this discussion differs from the original formulation in several ways. To obviate the need for the sorts of leading questions around researcher-determined foci that are characteristic of so-called text-talks, we use annotations, which are perhaps more authentic, but then use talks to clarify personal meanings of the independent annotations. In addition, rather than have awareness of the text purpose and audience, as well as critical perspectives on text in separate categories, they are placed in one—consistent with accounts of critical literacy (e.g.,

Baynham 1995).

Text-based movability, then, would be captured by annotations in which a student is drawing attention to specific information (e.g., by underlining, highlighting), commenting on vocabulary, paraphrasing bits of ideas, providing a detailed summary, and drawing inferences. With associative movability, the annotations would link text contents not only to personal experience (as envisaged in the original formulation), but also to a host of other types of intertextuality, as well as to selected emotions. With interactive movability, perhaps more appropriately re-designated critical text movability, annotations demonstrate an awareness of the need to interrogate social facts, purposes, and assumptions around the text.

Two measures are available for measuring movability (

Hallesson and Visén 2018). On the one hand, there is broad movability versus limited movability, which expresses the degree to which all movability types are visible in a student’s annotations. On the other hand, there is wide movability versus narrow movability, which measures the scope of issues instantiated within a particular form of movability. For instance, with the text-based form, the movability would be narrow if annotations contained mainly comments on vocabulary, rather than also concerns of text organisation, inferences, etc.

4. Method

The goal of this explorative study was to use annotations as basis for examining (i) what students attend to while reading, (ii) what their problem-solving strategies are, as well as the role of language and other semiotic systems in the process, (iii) their level of engagement with text, and (iv) how these insights could be leveraged for assessing and providing feedback on content reading, especially in a German but also international higher education environment in which enhancing students’ (metacognition of their) reading and capacitating content and prompting instructors to incorporate elements of reading instruction into their teaching have arguably become priorities.

To address these objectives, two sets of data were employed, namely, texts annotated by students and text-talks through which students’ interpretations of their annotations and other relevant information were elicited. In two courses (multilingual teaching, assessment) taught jointly in the 2020/2021 academic session by the researchers in an English Department of a German university, annotations were discussed as part of the programme. Students were subsequently invited to voluntarily share self-selected academic texts they had annotated. They were informed that the material was for research by the instructors and for use in future iterations of the courses. In total, 25 annotated texts were received.

Participants in the study were home language speakers of German. Across the skills of understanding, reading, writing, and speaking, they considered themselves advanced users of German (C in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages). With the exception of an occasional B self-rating, typically in writing or speaking, the participants equally considered themselves advanced users of English. They were either advanced undergraduate students or Master’s students. Irrespective of whether participating students’ degrees combined the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) with sports education, psychology, or political science, they all reported having had at least one non-EFL course that was taught in German but that had prescribed reading in English.

The 25 texts received ranged from one page of annotated text to complete journal articles of, on average, thirteen pages (not all of which were annotated). For this exploratory study, annotated texts in English and German from seven students were selected. The chosen samples illustrated very clearly a number of issues related to assessing and intervening in students’ reading. The texts were on a range of topics: intercultural communication, physical education, research methodology, the colonial and neoliberal politics of global English, and scholarship as a profession.

Besides the annotated texts, a second source of data was text-talks in which students commented on their annotations. Text-talks are structured discussions in which students individually engage a researcher around their understanding of text. In our case, the conversations were on annotated texts, and they were intended to elicit information that would suggest what text movability type/s (predominantly) underpinned students’ reading of text segments, of an entire text, or even of several texts. The text-talks took approximately 60 min each and were conducted in English via video conferencing or asynchronously through recorded audio responses to questions. The questions were on reading and annotation practices of students, specifically on the rationales for the annotations in the particular material submitted. Some relevant academic background information was also elicited on the student annotators (e.g., courses taken in combination with EFL, language proficiency self-rating, etc.). For this study, we draw on three such text-talks.

Participation in the study was voluntary and participants gave their consent in writing. The students were informed that the annotations submitted would not be used as part of the assessment for the courses and that they could withdraw their participation without reason at any point in time without any consequences.

We adopted an approach rooted in qualitative research (

Holloway and Galvin 2017), consistently with the two data sets (which foreground students’ own sense-making of their annotation and reading practices) and with the overall objective of drawing inferences for diagnostic assessment and capacity-building from students’ interpretations of their annotation practices. In other words, with the latter, we sought to engage in “reflective reconstruction and interpretation of the actions of others” (

Holloway and Galvin 2017, p. 25). Thematic analysis (

Braun and Clarke 2006) of transcribed text-talks, based on iterative readings of the academic material and the inscribed annotations, as well as a multimodal analysis of text and annotation, allowed for the identification of data relevant for addressing several of the objectives, namely, (i) what students attend to while reading, (ii) what their problem-solving strategies are, as well as the role of language and other semiotic systems in the process, and (iii) their level of engagement with text. Underpinning the multimodal analysis was the notion of resemiotisation (

Iedema 2003), which provided a framework for tracking how meanings and semiotic resources in text are transformed in corresponding annotations. The database arising from the foregoing was then employed in reflecting generally on the fourth objective on diagnostic assessment and on capacity-building.

Subsequent parts of this paper are organised as follows. In subsections of

Section 5, data and interpretations relevant to all or several of the first three objectives are presented, whereas

Section 6 offers an interpretation from the standpoint of diagnostic assessment.

Section 7 concludes the paper.

5. The Students’ Annotation Experience

After an initial overview of annotation practices (which presents some of the complementary information elicited in the text-talks), subsequent data sections allow us to see several issues that students attend to while reading, viz. structure, word meaning, dense text, and opportunities for offering rejoinders. The treatment of each such issue entails commentary on all or several of the problem-solving strategies used, as well as the role of language and other semiotic systems in the process, and the level of students’ engagement with text (as determined by movability types). It is important to reiterate that, while the students were enrolled in an English Department, the context was not one of language learning. They were all studying to become EFL teachers.

5.1. Overview of Annotation Practices

The participating students all claimed to annotate their academic texts. The thematic analysis of the text-talks revealed that there were specific contexts that determined the frequency of the practice. For instance, students reported consistently that they seldom annotated digital texts. Texts that were reported to be relevant to their future careers or in respect of which the lecturer had provided guiding questions were more likely to be often or sometimes annotated. The students reported a range of ‘styles’ regarding the look or aesthetics of the annotated page—from basic (using blue or black ink) to very colourful. Participants reported using annotations often for understanding content, and sometimes for both integrating text content to prior knowledge and critiquing text. Overall, annotations were reported to serve a number of functions: understanding the structure or organisation of a text and making connections between passages evident; translating/explaining words; drawing attention to key points; making it easy to respond to guiding questions; supporting the rapid recall of text contents when, after some time, the text has to be revisited.

With respect to the language of annotation, seldom would English be used to annotate a German text, but German would sometimes be used to annotate a text in English—suggesting that the students do activate their multilingual resources in processing text. A participant qualified this by claiming they would typically endeavour to annotate an English text in English, ostensibly to make their passage from annotation to written tasks in English a lot easier. In the following subsections, we present data relevant to each of five themes before discussing (in

Section 6) the data from the standpoint of diagnostic assessment.

5.2. Annotating for Structure

It emerged from the data that one issue students attend to while reading is the structure of the text. An example of the use of annotations to map out the structure or organisation of a text can be seen in

Figure 1.

In the text-talk, the author of the annotated page in

Figure 1 reported that, typically, when she has to read an academic text, she first skims through an initial set of (two to three) pages to see what she can glean of the text’s structure/organisation. She thereafter returns to the beginning to read in depth, annotating in the process. To return to

Figure 1, the initial skimming suggested some parallelism or contrasting set of points about the USA and Germany in Max Weber’s text on science [sensu scholarship] as vocation. We see in the annotation (note, for instance, the different colours used in underlining and numbering the points—green for Germany, red for the US) a form of intersemiotic translation (

Jakobson 1959). In other words, the annotation (in the form of colours, numbers) resemiotises the words, sentences, paragraphs, and formatting of the relevant part of the main text.

That initial skimming also alerted the student that the contrast ended somewhere in the middle of the second page, an awareness that, in turn, prompted a change in the colour of the pen (now black) used for underlining. Clearly, then, while for some observers (especially those who do not know German), the student’s annotations are of the null-content type (with the exception of the explanation in pencil of the inflected ‘plutokratisch’), these annotations nonetheless communicate and reflect meaning from the annotator’s standpoint. The curved line with an arrow, another null-content annotation, resemiotises lexical and grammatical cohesion in the text.

Let us briefly consider

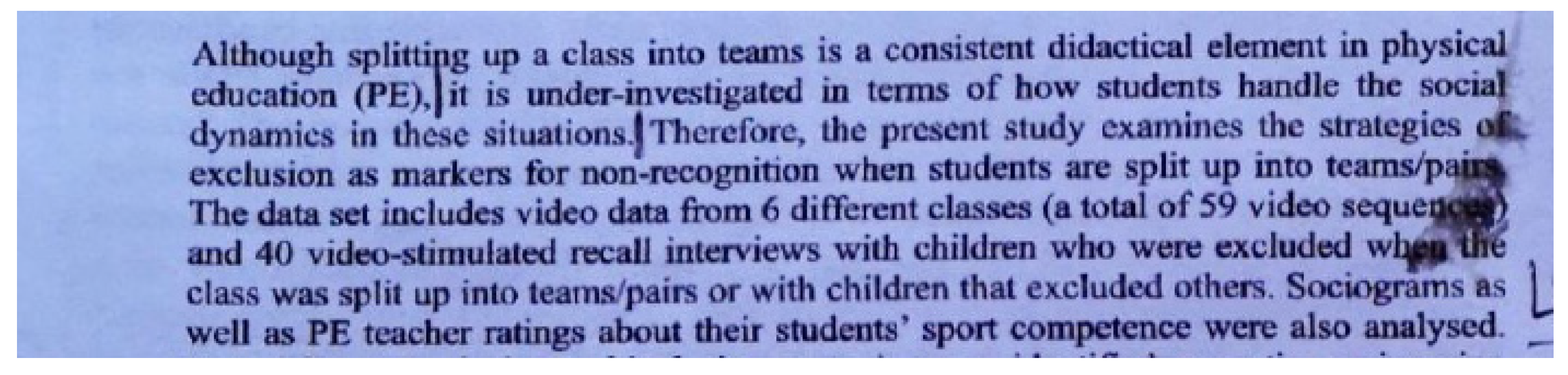

Figure 2 for another way of annotating for structure.

The student annotator here uses vertical bars to divide the first sentence into three parts. In text-talks, the student explained the decision as follows:

I drew the bars because … Mr. Antia in one of your seminars we talked about em different moves in abstracts and I think it was about this time that I also read the text so I guess I just wanted to see whether.. em this also applies to this article and well .. it did (chuckles)

The annotator, in other words, finds that Swales’ move 1 (establishing a research territory) applies to the subordinate clause, whereas the main clause exemplifies Swales’ move 2 (establishing a niche) (

Swales 1990,

2004;

Swales and Feak 2012). Again, the null-content annotations (the bars) have meaning for the student, as they are a resemiotisation of structural organisation (that is, moves) in the text.

These students’ annotations on mapping out the structure of texts exemplify text-based movability, which, as may be recalled, was operationalised as annotations that: draw attention to specific information (e.g., by underlining, highlighting); comment on vocabulary; paraphrase bits of ideas; provide a detailed summary; and draw inferences. The rather substantial form of engagement we see in the above annotations indeed underscores the point that text-based movability can be consequential. Rather than presupposing some facile notion of superficial or surface reading, text-based movability can, in fact, be associated with a form of engagement with text that is fairly consequential.

5.3. Annotating for Word Meaning

Another sub-theme in both the annotated material and the text-talks is that of word meaning. Indeed, one reportedly frequent use of annotation pivots around explaining/translating word meanings. The need may arise with respect to texts in German, but can also occur interlingually.

In one example based on a text by

Dörnyei (

2007, p. 112), the subheading in the chapter on quantitative research methods reads “Developing and piloting the questionnaire”. The student looks up the meaning of ‘pilot[ing]’ in a bilingual English–German dictionary, and selects a meaning (‘steuern’) that is not relevant to the context of trying out questionnaire items on a small group before the final questionnaire is administered. The equivalent selected and used for the annotation, ‘steuern’, is more relevant to vehicles or metaphorical uses of ‘steering’. Albeit incorrect, the annotation illustrates interlingual resemiotisation.

In

Figure 3, we find an example of a student attempting to infer word meaning (‘commodified’).

The student uses a question mark to indicate a hypothesis concerning ‘commodified’ as meaning (German) ‘kommerzialisiert’. Her hypothesis is correct. In other words, the English ‘commodified’ is resemiotised as the equivalent (‘=’) ‘kommerzialisiert’. This is yet another indication that students may process meaning multilingually while reading.

The use of inference as a means for determining word meanings is also evident in the annotation in

Figure 4, as well as in the particular student’s reflections.

For ‘Einfall’, a bilingual German–English dictionary (e.g.,

https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/german-english/einfall, accessed on 11 October 2021) would list meanings such as the following: idea, notion, invasion, incidence, onset. In interpreting (during the text-talk) the annotations with the body and the null annotations in

Figure 4, the student was concerned with Max Weber’s usage of the word ‘Einfall’. She is unable to see the link between these common meanings and the context of Weber’s text, which involves a description of: the different work orientations of the amateur (‘Dillettant’) and the expert (‘Fachmann’), and of the differences between work (‘Arbeit’) and the problematic ‘Einfall’. The student records in pencil her inference of what she sees as Weber’s somewhat idiosyncratic usage: ‘Arbeit’ (work) + Leidenschaft (passion) = Einfall’. In other words, her annotation is a mathematical type notation, or resemiotisation, of the paragraph. On our reading, her interpretation appears to be logical.

5.4. Annotating Graphically to Unpack Dense Text

The data on annotations and text-talks also point to dense or complex information as an aspect of text that students may attend to, and how they might go about it. It was seen that, besides underlines, highlights, text, punctuation marks, and so on, students may sometimes draw diagrams to annotate. Indeed, a need to visualise information that is particularly dense in text is one reason why a student’s annotation may take the form of a graphical depiction, as is the case with

Figure 5. A backdrop to

Figure 5 is how perceptions of the athleticism of peers get factored into negotiations of value in team selections in school sports; in other words, who is preferentially recruited into a team (and in what sequence). In the middle of the first page of

Figure 5, the author is describing a video-recorded observation of children on a school playground forming two opposing teams.

Although the author of the article (Grimminger) diagrammatically represents the sequence (on a following page), the student-annotator had not noticed this, and goes ahead to draw their own diagram at the bottom of the first page. We see the two captains, Noah and Matt, and under each, we see members selected unproblematically. The two least athletic peers (i.e., Tami and Fiona) are placed in the middle, and have a question mark against their names. Tami is represented as initially going to Matt’s team, but this decision is reversed, as seen by the short lines across the curved arrow. Tami and Fiona ultimately end up in team Noah. The student annotator’s rationale is as follows:

I em didn’t represent the other case studies .. em graphically because em . they weren’t as complex as this one so I didn’t need to represent it . em to understand it .. em this one was more complex so I wrote the names down and drew the arrows to em .. to get a better understanding of the situation

What we see here is how a detailed textual transcript of a video-recording of team selection decisions is resemiotised as a combination of: spatial representation (notice the use of space to recreate a scene); curved arrows—some crossed; a big question mark; names, the key ones (captains) being encircled. Interestingly, when asked about what they thought of the text author’s own graphic representation, the student-annotator preferred their own, finding it much clearer. In our tripartite distinction of movability types, the student’s action here which has led to the unpacking of dense text still qualifies as text-based movability.

The annotations reviewed above collectively exemplify wide text-based movability because of the range of issues instantiated within this type of movability. In the sections that follow, we provide data that illustrate other movability types.

5.5. Annotating for Intertextuality

Our data also suggest that making intertextual connections is another issue that students attend to while reading, and this is reflected in their annotations. Building on

Bakhtin’s (

1987) work, Fairclough considers that the “intertextuality of a text is the presence within it of elements of other texts (and therefore potentially other voices than the author’s own) which may be related to (dialogued with, assumed, rejected, etc.) in various ways” (

Fairclough 1992, p. 218). One such example of establishing connections is illustrated in

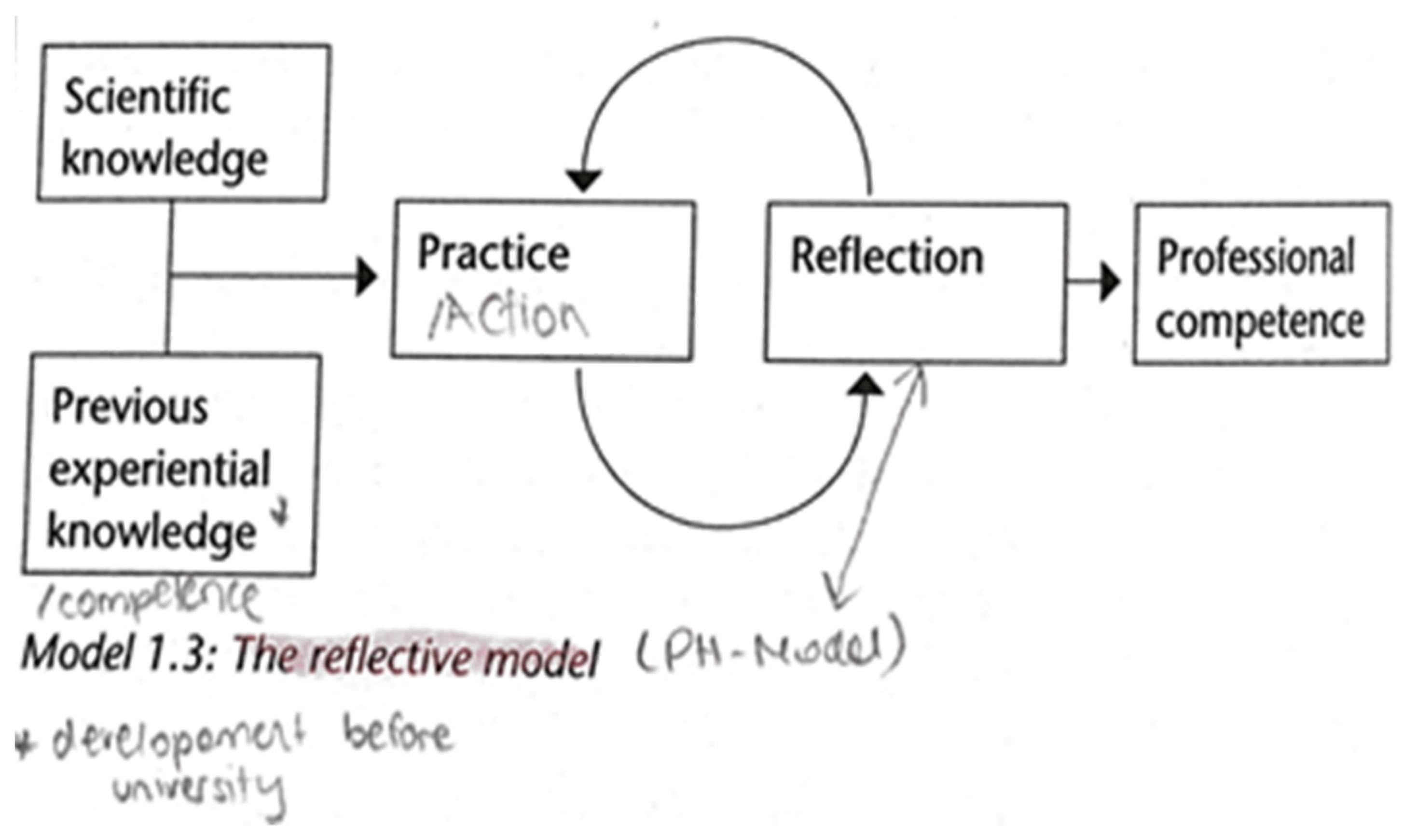

Figure 6.

The student explains the pencilled annotations as her attempt to read the ‘reflective model’ of teacher training in

Figure 6 through a conceptual vocabulary that is associated with her institution, which she abbreviates as ‘PH’ in ‘(PH-Model)’. The components of the model represent the pillars of foreign language teacher education implemented at her university. Besides signalling her recognition of the model, the student draws on other literature that she is familiar with to suggest terminology synonymous to the one used in the PH model. Clearly, then, the student’s actions establish two intertextual directions. From her knowledge of previous PH texts, she annotates in a way that shows that she recognises the model in the current text as being associated with PH. From her knowledge of other texts, she proposes terminology (‘/Action’, ‘/competence’) that complements the terms used in PH. The student’s action of consciously building connections to previous ‘texts’ or knowledge exemplifies the form of text engagement referred to as associative movability.

5.6. Annotating as Rejoinder

The previous section referred to Bakhtin’s account of intertextuality. Besides acknowledging previous texts or voices, an annotation in a text being read can also polemicise with these previous texts or voices, interrogating and challenging them. The third form of engagement with text, critical movability, is all about questioning, refuting, pushing back, or reading against the grain. Consider

Figure 7, a null-content annotation, and

Figure 8, a blend of null-content annotation and annotation with a body.

In the text-talk explaining this null-content annotation, the student said:

Colonialism was … an exploitation everywhere… so erm why different in Philippines? I marked this because I disagree with . English .. the language of the oppressor cannot make the oppressed democratic. So the people were uncivilised and now English has made them civilised. This doesn’t make sense.

The student is clearly put off by this messianic characterization of English and of American colonialism on the one hand and, on the other, the deprecation of the Philippines. She was particularly irked by the implicature that civilization in the Philippines was being touted as the outcome of the privilege the country had in experiencing American colonialism. The student’s highlighting of the passage, then circling of the word ‘civilized’, communicates that she is capable of attending to contentious points in text, and that, in this particular instance, she is reading against the grain, offering a counter-reading of the passage. Unlike in preceding examples where the semiotics employed in the annotations were seen in relation to the semiotics in the main text, in the current example, it would seem that it is a strong emotion triggered by the text that is resemiotised in the annotation as pink highlighting and circling.

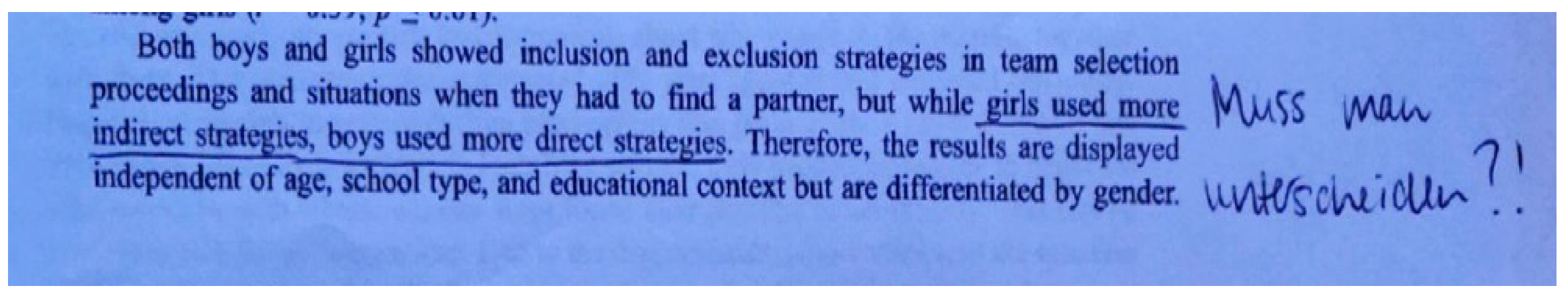

In the annotation in

Figure 8, we see another ‘engaged’ student reader, equally making it clear that students do attend to potentially contentious points in text. The student-annotator, recognizable from previous excerpts on the team selection article, wonders about the point of a reporting on team selection that evokes gender.

In reflecting on the annotation ‘Muss man unterscheiden’ (German for: should a distinction be made?), as well as the question mark and exclamation mark, the student says:

I wrote it in German because I think as I said before. I think in German when thinking about this topic because my [Bachelor’s] thesis was in German and I am em . was just wondering if you have to make a distinction between girls and boys within this topic … and this is also why I put a question mark and exclamation mark because first .. I am wondering if you have to do this and also … it’s also like a statement because I don’t think you should make a distinction if you know what I mean. {Chuckles}.

We see here a reaction triggered by a text in English being expressed in the annotation in German. In summing up, what this and previous examples show is that, without prejudice toward how correctly it is carried out, there are a range of issues in text that students attend to while reading and annotating: structure, word meanings, dense information, how a current text links to a previous text, and opportunities for polemicisation. In addressing each of these issues, students adopt a range of resemiotisation strategies through which we are able to see how they recontextualise within annotation corresponding passages they encountered in the main text. As strategies, we see shifts from text in one language (in an article) to text in another language (in annotations), but there is also obviously the use of the same language across both sites (article and annotation). We also see other kinds of shifts: from text to curved lines; from text to underlines, highlights, circling; from text to a combination of spatial arrangement, curved arrows, question marks, names; etc.

6. Discussion: Evidence-Based Diagnostic Assessment

Diagnostic assessment involves determining areas of strength in a learner’s demonstration of a particular skill or ability, and areas of some concern, and then using this information to improve learning. It was also seen that the rationale for using annotations as a basis for a diagnostic assessment of reading was derived from a view such as that expressed by Liu, which states that “[r]eviewing a student’s annotated text conveniently offers a window through which a teacher may discern a learner’s thinking styles and find effective ways to facilitate each learner’s critical thinking process” (

Liu 2006, p. 194).

In highlighting the obvious strengths and areas of concern in students’ reading, the data discussed in the previous sections can guide and inform both teaching and learning by drawing attention to (i) what may be attended to in text, and (ii) through what strategies, in order to (iii) achieve particular ends. The following discussion is framed as capacity-building in the area of reading for both content instructor and students—the former, to be able to incorporate elements of reading into their teaching on the basis of diagnostic assessment, and the latter, to enhance their metacognition and to foster peer assessment. Building on the foregoing, a possible teaching environment for implementing a diagnostic assessment of reading on the basis of annotations is sketched.

It was seen from the data that one issue that the participants in the study attended to was text organisation, a point that has implications for understanding, recall and metacognition, etc. In equipping themselves theoretically to identify and make sense of data, such as those that were presented in

Figure 1 (contrasting set of points about the USA and Germany in Max Weber’s text on science as vocation) and

Figure 2 (segmenting text to reflect Swales’ moves), a content instructor can be guided by views in the literature, such as the following:

“[t]he recognition of an organizational pattern enables the student to form a mental representation of the information and to see the logical relationships advanced by the author” (

Lo et al. 2013, p. 415;)

“reading comprehension and the recall of information are dependent on a student’s ability to recognize organizational structures” (

Lo et al. 2013, p. 415;)

“Metacognitive reading strategies are conscious means by which students monitor their own reading processes including evaluating the effectiveness of cognitive strategies being used. Metacognitive strategies may involve, for example, planning how to approach the reading of a text, testing, and revising according to purpose and time available” (

Karbalaei 2011, p. 7).

A content instructor may easily draw attention to how the annotations by the student in

Figure 1 represent some strength or useful skill that needs to be reinforced. It is useful because it enables the student to see how the arguments in that particular part of the text are structured (as a set of contrasts). This information conceivably enables the student to “[plan] how to approach the reading of [the] text (

Karbalaei 2011, p. 7). Recall that the student in question had, in fact, said that she initially skims through a couple of pages to essentially know how to approach the reading task. It is also conceivable that the student’s colour codes (green for Germany, red for the US) and numbering of the arguments aid recall, or at least help in remembering that there were x number of contrasting points between the US and Germany. In summary, in identifying this student’s annotation or marking up of text organisation as a strength and in providing (reinforcing) feedback, the instructor is validating this practice as one that should be demonstrated in, or that should guide, future approaches to text.

There are teachable moments in the form of opportunities for diagnostic assessment associated with the data on word meaning: the use of a dictionary in connection with the German ‘steuern’;

Figure 3 on inferring the German meaning of the English ‘commodified’, and

Figure 4 in deciphering Max Weber’s idiosyncratic usage of the German ‘Einfall’. In equipping themselves for diagnostic assessment of students’ approaches to word problems in text, a content instructor might be guided by scholarship, making points such as the following:

“Students must however be brought to realize that a dictionary only forms part of a problem-solving package […]. Even an unabridged dictionary can never be more than a collection of guidelines for understanding and producing words and expressions. In most cases students must use their own […] knowledge for interpreting dictionary entries” (

Carstens 1995, p. 112);

A word may be polysemic, and this means that a dictionary may list several senses of such a word. The reader needs to be able to use cues from both the text and (where applicable) the dictionary to determine the sense relevant to the text (

Carstens 1995);

A word may be used with a peculiar, idiosyncratic, or text-specific meaning, in which case, the reader needs to use cues in the text to infer the meaning intended (

Antia 2022).

On the basis of scholarship, such as that exemplified above, a content instructor is able to locate the source of the error in the annotation where a student used a bilingual dictionary and glossed ‘piloting’ (as in questionnaires) into German as ‘steuern’ and explain to the student why the choice of this equivalent was wrong and what would have been the appropriate sense, in addition, of course, to building the student’s capacity to use the dictionary better in future reading tasks. Even if the content instructor is unable to teach how to use the dictionary, they can at least pass on this ‘diagnostic’ information to a relevant student support centre in the institution.

Faced with the annotation on ‘commodified’ being glossed as (German) ‘kommerzialisiert’, the instructor is easily able to reinforce the idea of logical and informed inferencing, or using one’s own knowledge to infer word meaning. Recall that, although she had guessed that ‘kommerzialisiert’ was an equivalent word, she still placed a question mark next to it, signalling her preparedness to engage in the metacognitive activity of monitoring and revising (if need be) as the text unfolds, in a process known as dynamic reading, which is contrasted with synoptic reading (

Antia 2022). Again, this is a practice worth drawing attention to and reinforcing. Similarly, the Max Weber ‘Einfall’ annotation would reinforce this same point, especially because idiosyncratic or text-specific usage of words does arise on occasion, and a dictionary is not of much help (

Antia 2022). Interestingly, rather than consult a dictionary, the student attempts to use text clues to infer what the components of this odd usage are, and identifies them correctly. Collectively, these examples provide the instructor with an opportunity to use diagnostic evidence to provide remedial or behaviour-reinforcing feedback.

The resemiotisation of textual material into the image or semiotic ensemble seen in the annotation in

Figure 5 provides further data for gleaning insight into how students are reading and what feedback can be given, so that the practice is seen as useful. In broaching this topic, a content instructor may well refer to scholarship similar to

Harvey and Goudvis (

2007), which suggests that the creation of (mental) images makes it possible, among other things, to fill in missing information, to understand dimensions of space/size or of the sequence of activities, and to attend very closely to the text. These are all claimed to strengthen the reader’s relationship to the text, enhance recall, and heighten reading pleasure. Clearly, representing dense meaning (correctly) across semiotic systems is both a process and an outcome that is indexical of understanding having taken place or taking place. Using evidence such as

Figure 5, an instructor is able to provide reinforcing feedback to students around the visualisation of text contents as a valuable reading strategy, and one that is potentially indicative of a deep engagement with text.

While the data discussed above illustrate opportunities for a diagnostic assessment of text-based movability, the annotation in

Figure 6 on the ‘PH’ reflective model of teaching presents an opportunity for a diagnostic assessment of what was referred to as associative movability. Similarly, the text-talk with respect to the text markup motivated by the student’s previous encounter with Swales’ moves also points to associative movability. To broach data on connections established in annotations between a current text and previous texts, emotions, or biographical experiences, an instructor might draw on some of the scholarship in the neurobiology of learning. It has been well known for a while now that learning (e.g., from a text) is enhanced when, unconsciously or consciously, the learner/reader allows associations to be formed in brain cells (

Owens and Tanner 2017). The rewards of dense brain cell connections include an enhanced understanding, metacognition, and recall. One visualises ‘light bulb moments’ as students are able to make connections to a lecture on academic writing or to the scholarly approach or philosophy of an institution. On the basis of such insights, an instructor is able to provide reinforcing feedback on an annotation, such as the one in

Figure 6, in which, the student draws on previous texts to signal the institutional context that they associate the particular model with and to provide terminology synonymous to the one used in the model.

Finally, with respect to how diagnostic assessment may be applied to the service of developing or reinforcing critical movability in student readers, we find teachable moments in the annotations associated with

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. Scholarship emphasises the need in conceivably most fields for student readers to be able to:

explore or read the connections between language, knowledge, and power, as well as to interrogate the “origins and implications of assumptions as well as other possibilities for signification” (

Andreotti 2014, p. 13).

A content instructor can draw on the above lines of scholarship in framing or deconstructing what is happening in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, providing reinforcing feedback that validates the relevant annotations as helpful for engaging with text and, ultimately, for developing students as critical readers and for extending the frontiers of knowledge. In the annotation in

Figure 7 on English in the Philippines, an instructor is easily able to recognise and validate the student’s interrogation of the “origins and implications of assumptions” (

Andreotti 2014, p. 13) concerning the ‘civilising mission’ of American colonialism and American English. Such an interrogation would naturally lead to questions such as: who is the author of this belief? What are their intentions? Who is the addressee?

How might this all work in practice? There are several ways of creating higher education teaching environments in which annotated texts can be used for a diagnostic assessment of students’ reading in content areas. We describe here one modality that we are piloting that is intended to allow for diagnostic feedback by both instructors and student peers. Students are introduced to basic notions of annotation, reading levels, and text movability, such as those that can be gleaned from the introduction and literature review of this article, as well as from an animated video (

https://youtu.be/Ca4KFStEpKs, accessed 14 January 2022). At the very latest, two weeks ahead of a lecture on topic x, the instructor posts (excerpts of) a key reading in the course folder on the institutional learning management system. Students are given the following four tasks:

They download the prescribed reading (extract), annotate it, and upload their annotated texts to an assignment subfolder;

Each student is requested to review two or three annotated texts other than their own, and to annotate on the annotations to communicate agreement, disagreement, or insights gained;

During a phase of pair or group work, students share their annotations, gleaning additional insights on the text;

Adding their insights from the previous collaborative phase, students prepare to either present in plenary their own annotation or their comments on the annotations they reviewed, if they happen to be among the two or three students the instructor calls upon in class.

The instructor would have skimmed through the ‘annotated annotations’ ahead of the class on topic x to identify material of particular interest for the intended class objectives. This foreknowledge then serves as a basis for calling on one or two students to present on their pre-class task. With this arrangement, potentially helpful peer-to-peer diagnostic feedback is offered through a collaborative learning environment, in addition, of course, to the instructor’s feedback. In this process of peer-to-peer annotation, students are presumably able to negotiate meaning and to be inspired to engage in (further) intensive discussion and reflective inquiry; they become aware of a wide repertoire of reading strategies; this social, rather than individual, learning experience can be expected to ultimately deepen understanding. The instructor’s sense of how the prescribed text has been understood or engaged with (through the annotations) is easily able to inform how teaching and discussion are carried out in class, and what (further) assessment tasks are most supportive of students’ access to the literature. In other words, instructional decisions may, in part, derive from the insights yielded by learners’ annotations and discussions thereof.

7. Conclusions

This article has illustrated how text annotation can be leveraged for an evidence-based assessment of, and instruction in, content specific reading. We have shown how instructors can use annotation data and scholarship on reading to build their own capacity in offering diagnostic assessment of students’ reading, especially at a time when the need for reading instruction is increasingly recognised in higher education and there is concern that there is limited capacity for this task outside of educational support or academic literacy centres. We have also suggested that, through a process of peer diagnostic feedback on annotated texts, students themselves might be able to enhance the quality of their engagement with text. These diagnostic assessment potentials of annotations have been illustrated in a number of areas: unpacking the structure or organisation of text; determining relevant word meanings; text visualisation; intertextual connections; rejoinders to text content.

There are obvious limitations to this exploratory study, none the least of which is its small size, which obviously constrains the validity of any generalisations that might otherwise have been made. Small scale studies have their value in generating hypotheses for further research. There is a second limitation, which has to do with using annotations as proxy for process data in reading. As widespread as annotations are in the reading experience of university students, the fact remains that not every student annotates, nor is every cognitive process taking place during reading captured in annotations. This is, however, a challenge associated with many kinds of proxy data that has not limited their usefulness. For instance, in empirical translation studies, think or talk-aloud protocols are used to elicit (introspective) data on the goings-on in a translator’s mind. Decades of experience in this field indicate that although think-aloud data are proxy and imperfect data, they nonetheless have yielded insights that have informed professional training (

Lörscher 1991).

One outstanding question is how culture shapes annotating behaviour, and what the impact of this influence might be on the instructor’s diagnostic assessment of students’ reading. This is an especially relevant question in an era of internationalisation of higher education. To offer one example,

Hofstede’s (

1986) dimensions of culture (

Hofstede et al. 2010), particularly the power distance index, have been reported to shape the level of critical awareness with which students approach their learning (which obviously includes reading). Disregarding any inferences of essentialization, studies have found that students from hierarchical, high power distance cultures, where power is unequally distributed, are less likely to offer rejoinders to the authority of the instructor and text compared to students from low power distance cultures, where power is more laterally distributed (

At-Twaijiri and Al-Muhaiza 1996;

Manikutty et al. 2007). In a class with students from diverse international backgrounds, an instructor might clarify for the students the culture dimensions that undergird coming-to-know processes in the discipline, institution, and/or class, and then work out the implications for students’ reading and annotation behaviours.

In the foreign language and culture class, research on the use of annotations for both a teacher-led and peer-to-peer diagnostic assessment of students’ reading is probably promising in the insights that it could yield. Our focus in subsequent work will, however, be to build on the pilot described earlier in order to address some of the above limitations, and to especially explore how social and academic cultures across national institutions might shape the thrust of students’ annotations (in terms of movability types).