Why Is Inflectional Morphology Difficult to Borrow?—Distributing and Lexicalizing Plural Allomorphy in Pennsylvania Dutch

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Kissi → Kissi-s ‘pillow/pillows’

- Schnuppi → Schnuppi-s ‘hankie/hankies’

- Hammer → Hammer-s ‘hammer/hammers’

- Mick → Mick-e ‘fly/flies’

- Schtick → Schtick-er ‘piece/pieces’

- Haus → Heis-er ‘house/houses’

- Hand → Hend ‘hand/hands’

- Frein → Frein ‘friend/friends’

- RQ1: Do the syntactic structures, i.e., spans, that we employ in our analysis explain allomorphy selection in language contact scenarios, particularly by constraining the borrowing of inflectional morphology?

- RQ2: How successful is our spanning-based approach in modeling allomorphy in morphological plural marking in Pennsylvania Dutch?

2. Plurality in Pennsylvania Dutch: Allomorphic alternations

2.1. Trochaic Structure in (Standard) German vs. Pennsylvania Dutch

2.2. Characteristics of PD Plural Exponents

3. OFOH-Architecture

3.1. Features and Contrast

3.2. A Brief Overview of the Syntax of num

- (2)

- Hebrew: construct state

- beyt ha-morahouse the-teacher‘the teacher’s house’

- *ha-beyt ha-morathe-house the-teacherIntended: ‘the teacher’s house’

- (3)

- Hebrew: free state

- bayit ʃel ha-morahouse of the-teacher‘a house of the teacher’s’

- ha-bayit ʃel ha-morathe-house of the-teacher‘the teacher’s house’

- (4)

- Armenian

- yergu had hovanoc uni-mtwo cl umbrella have-1s‘I have 2 umbrellas.’

- yergu hovanoc-ner uni-mtwo umbrella-pl have-1s‘I have 2 umbrellas.’

- *yergu had hovanoc-ner uni-mtwo cl umbrella-pl have-1s‘I have 2 umbrellas’ (Borer 2005, p. 39)

- (5)

- Persian

- sæg did-æmdog see.past-1sg‘I saw dogs’

- sæg-a-ro did-æmdog-pl-omsee.past-1sg‘I saw the dogs.’ (Gomeshi 2003, p. 48)

- (6)

- Distributed num projections (Wiltschko 2021, p. 190)

- (7)

- Syntactic representation for Pennsylvania Dutch plural

- (8)

- Syntactic representation for English plural

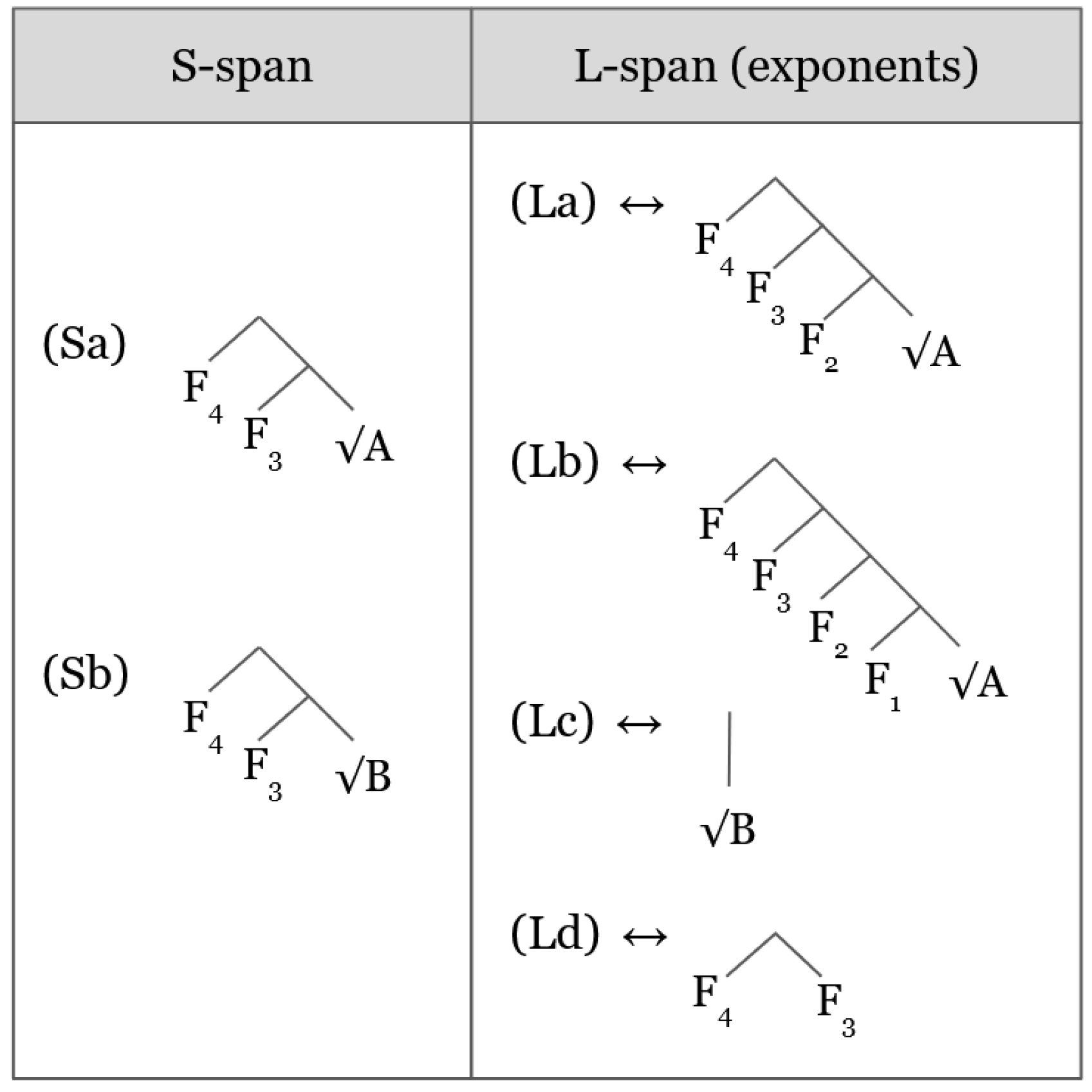

3.3. A Spanning Approach to Distributed num

- (9)

- Span:An n-tuple of heads is a span in a syntactic structure S, iff is the complement of Xn in S.

- (10)

- Exhaustive Lexicalization Principle:Every syntactic feature must be lexicalized. (Fábregas 2007, p. 167)

- (11)

- Superset Principle:In case a syntactic span does not have an identical match in the lexical repertoire, select an exponent which contains a superset of the features present in the syntactic span.(Adapted from Fábregas and Putnam 2020, p. 40)

- (12)

- Subsect S-span:In case no exponent contains a superset of the features present in the S-span,

- select the exponent whose L-span contains as many features present in the S-span as possible, then

- apply (a) until the Exhaustive Lexicalization Principle obtains.

- (13)

- Insertion Heuristic:When an S-span is spelled out, exponents are inserted according to (a). If (a) cannot obtain, exponents are inserted according to (b). If (b) cannot obtain, then (c) applies:

- Superset Principle

- Subsect S-span

- No insertion

| (14) |  | (15) |  |

4. A Distributed Account of Plurality in Pennsylvania Dutch

- (16)

- S-span representing PD distributed plurality, from (7)

- (17)

a. b.

- (18)

a. b.

- (19)

a. b.

- (20)

a. b. - (21)

a. b.

5. Distributed Plurality in a Bilingual Lexicon

- (22)

- English distributed plural S-span, from (8)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C-I | Conceptual-Intentional |

| DM | Distributed Morphology |

| NS | Nanosyntax |

| L-Span | Lexical-span |

| LF | Logical Form |

| OFOH | One Feature One Head |

| PD | Pennsylvania Dutch |

| PF | Phonological Form |

| SG | Standard German |

| S-Span | Syntactic-span |

| XS | Exo-skeletal Syntax |

| 1 | This is also our understanding of stem vowel alternations such as umlaut patterns. Other treatments, specifically for German, e.g., Wiese (1996a) and more recently Trommer (2021), adopt a phonological analysis via floating features. It is in principle possible in our model to associate features to syntactic structures. For the current discussion, we view alternations of this type as involving distinct candidates (see De Belder (2020) for an allied approach to Dutch plural allomorphy). Yet, for both perspectives the presence vs. absence of umlaut is suppletive in nature. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | While we readily acknowledge that certain tendencies in plural allomorphy in PD may be related to different gender feature values (e.g., {r} plurals tend to be found with historically neuter nouns such as Hemm-er ‘shirt-pl’), we also recognize that these tendencies are not direct indicators of particular plural reflexes. We leave the complex interaction between gender and number features for future research. |

| 4 | In PD, /r/ is typically vocalized as [ɐ] in codas, occurring an approximant [ɹ] elsewhere (Louden and Page 2005). These phonological alternations do not affect the current analysis. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | An important part of the investigation of number marking in the morphology of language concerns its semantic interpretation and its relation to singular marking. Due to time and space considerations we do not elaborate on these matters here. The reader is referred to Harbour (2014) and Scontras (2022) for a detailed overview. |

| 8 | We do not assume that the order in which features are merged is constrained by UG. Instead, we follow Ramchand and Svenonius (2014) who argue that in principle features can be merged in any order. Well-formed syntactic spans are, however, constrained by interface conditions on the interpretability of such structures, which in fact yields a very limited number of combinatorial possibilities for any given set of features. |

| 9 | |

| 10 | We assume furthermore that each derivation proceeds in a cyclic fashion, meaning that the feature inventory, the syntactic component, and the lexicon are accessed in an iterative manner over the course of constructing one representation. Therefore, once a particular S-span ‘chunk’ has undergone insertion, it may return to the syntactic component to participate in further structure building operations and, subsequently further rounds of spell out. We will not focus on the nature or details of cyclic spell out in this paper, but see no need for representational constraints on the sizes of spans (see Newell (2017) for a similar proposal). |

| 11 | Crucially, although Subsect S-span does involve an exponent spelling out the largest possible subset of the features in an S-span, there are two reasons why it does not straightforwardly equate to the Subset Principle of DM. Firstly, insertion according to Subsect S-span, works on the basis of overspecified exponents (i.e., L-spans on competing exponents may contain features not present in the S-span), whereas insertion according to the Subset Principle involves underspecified exponents (i.e., competing exponents cannot contain features that are not present in the syntactic structure). Secondly, Subsect S-span is driven by the Exhaustive Lexicalization Principle (on which every syntactic feature must be lexicalized), whereas the Subset Principle does not require every syntactic feature to be lexicalized. |

| 12 | The English {s} plural is in fact /z/, which is unspecified for laryngeal features, rather than ‘voiced’ (Iverson and Salmons 1995). Because PD lacks a contrast between /s/ and /z/ (there is no specification required) and because PD speakers tend to pronounce English /z/ as [s] (Louden and Page 2005), we are confident in viewing English /z/ and PD {s} as referring to the same phonological category. |

| 13 | Of course, with this statement we arrive at an interesting open question as to whether or not all S-spans here are similar in structure and content. Can the conceptualization of ‘language mode’ mediate where the exact cut-off point would be for lexicalization, or is this an instance of highly variable behavior which is subject to individual ‘proficiency’? |

References

- Aboh, Enoch Oladé. 2015. The Emergence of Hybrid Grammars: Language Contact and Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Acquaviva, Paolo. 2016. Structures for plurals. Lingvisticœ Investigationes 39: 217–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuaviva, Paolo. 2008. Lexical Plurals: A Morphosemantic Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, David, and Peter Svenonius. 2011. Features in minimalist syntax. In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Minimalism. Edited by Cedric Boeckx. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2011. Plural mass nouns and the morpho-syntax of number. In Proceedings of the 28th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL28). Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, vol. 33, p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2021. Lexical plurals. In The Oxford Handbook of Grammatical Number. Edited by Patricia Cabredo Hofherr and Jenny Doetjes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 242–56. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Maya. 2003. Locality constraints in the interpretation of roots: The case of Hebrew denominal verbs. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 21: 737–78. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Maya. 2005. Roots and Patterns: Hebrew Morpho-Syntax. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Barbiers, Sjef. 2008. Microvariation in syntactic doubling—An introduction. In Microvariation in Syntactic Doubling. Edited by Sjef Barbiers, Olaf Koeneman, Marika Lekakou and Margreet van der Ham. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Baunaz, Lena, and Eric Lander. 2018. Nanosyntax: The basics. In Exploring Nanosyntax. Edited by Lena Baunaz, Karen De Clerq, Liliane Haegeman and Eric Lander. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–56. [Google Scholar]

- Biberauer, Theresa. 2019. Factors 2 and 3: Towards a principled approach. Catalan Journal of Linguistics, 45–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bjorkman, Bronwyn M., and Daniel Currie Hall, eds. 2020. Contrast and Representations in Syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blix, Hagen. 2021. Spans in South Caucasian agreement: Revisiting the pieces of inflection. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 39: 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2012. Universals in Comparative Morphology: Suppletion, Superlatives, and the Structure of Words. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, Geert. 1998. Phonological output constraints in morphology. In Phonology and Morphology of the Germanic Languages. Edited by Wolfgang Kehrein and Richard Wiese. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, pp. 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring Sense: Volume I: In Name Only. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Joshua R. 2011. Religious Identity and Language Shift among Amish-Mennonites in Kishacoquillas Valley, Pennsylvania. Ph.D. thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Joshua. 2019. The changing sociolinguistic identities of the Beachy Amish-Mennonites. Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies 7: 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Joshua R., and Douglas J. Madenford. 2009. Schwetz mol Deitsch! An Introductory Pennsylvania Dutch Course. Morgantown: Masthof Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buffington, Albert F. 1970. Similarities and dissimilarities between Pennsylvania German and the Rheinish Palatinate dialects. Pennsylvania German Society 3: 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Caha, Pavel. 2009. The Nanosyntax of Case. Ph.D. thesis, University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Caha, Pavel. 2017a. How (not) to derive *ABA: The case of Blansitt’s generalisation. Glossa: A Journal of General Lingusitics 2: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caha, Pavel. 2017b. Suppletion and morpheme order: A unified account. Journal of Linguistics 53: 865–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caha, Pavel. 2018. Notes on insertion in Distributed Morphology and Nanosyntax. In Exploring Nanosyntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Christmann, Ernst. 1950. Das Pennsylvaniadeutsch als pfälzische Mundart. Rheinisches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 1: 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and Functional Heads: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cowper, Elizabeth, and Daniel Currie Hall. 2014. Reductiō ad discrīmen: Where features come from. Nordlyd 41: 145–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dali, Myriam, and Éric Mathieu. 2021. A Theory of Distributed Number. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- De Belder, Marijke. 2020. A split approach to the selection of allomorphs: Vowel length alternating allomorphy in Dutch. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5: 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeClerq, Karen, and Guido Vanden Wyngaerd. 2017. * ABA revisited: Evidence from Czech and Latin degree morphology. Glossa: A Journal of General Lingusitics 2: 69. [Google Scholar]

- Dékány, Éva. 2021. The Hungarian Nominal Functional Sequence. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dresher, B. Elan. 2009. The Contrastive Hierarchy in Phonology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dresher, B. Elan, Glyne Piggott, and Keren Rice. 1994. Contrast in Phonology: Overview. In Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics. Edited by Carrie Dyck. Toronto: Department of Linguistics, University of Toronto, Number 13. pp. iii–xvii. [Google Scholar]

- Embick, David. 2015. The Morpheme: A Theoretical Introduction. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Embick, David, and Rolk Noyer. 2001. Movement operations after syntax. Linguisitic Inquiry 32: 555–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fábregas, Antonio. 2007. The exhaustive lexicalization principle. Nordlyd 34: 130–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fábregas, Antonio, and Michael T. Putnam. 2020. Passives and Middles in Mainland Scandinavian: Microvariation through Exponency. Berlin: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Rose, Katharina S. Schuhmann, and Michael T. Putnam. 2022. Reducing the role of prosody: Plural allomorphy in Pennsylvania Dutch. In WILA 12 Proceedings. Edited by Kelly Biers and Joshua R. Brown. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, J. William. 1985. A Simple Grammar of Pennsylvania Dutch. Lancaster: John Baers & Son. [Google Scholar]

- Gardani, Francesco. 2008. Borrowing of Inflectional Morphemes in Language Contact. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, Jean Berko. 1958. The Wug Test. Cambridge: Larchwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldrick, Matthew, Michael T. Putnam, and Laura S. Schwarz. 2016. Co-activation in bilingual grammars: A computational account of code mixing. Bilingualism: Language an Cognition 19: 857–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gomeshi, Jila. 2003. Plural marking, indefiniteness, and the noun phrase. Studia Linguistica 57: 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, François. 2008. Studying Bilinguals. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Daniel Currie. 2007. The Role and Representation of Contrast in Phonological Theory. Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Daniel Currie. 2020. Contrast in syntax and contrast in phonology: Same difference? In Contrast and Representations in Syntax. Edited by Bronwyn M. Bjorkman and Daniel Currie Hall. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 247–71. [Google Scholar]

- Harbour, Daniel. 2014. Paucity, abundance, and the theory of number. Language 90: 185–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, Heidi. 2009. Compounding in Distributed Morphology. In The Oxford Handbook of Compounding. Edited by Rochelle Lieber and Pavol Štekauer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 129–44. [Google Scholar]

- Heycock, Caroline, and Roberto Zamparelli. 2005. Friends and colleagues: Plurality, coordination, and the structure of DP. Natural Language Semantics 13: 201–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofherr, Patricia Cabredo, and Jenny Doetjes, eds. 2021. The Oxford Handbook of Grammatical Number. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson, Gregory K., and Joseph Salmons. 1995. Aspiration and laryngeal representations in Germanic. Phonology 12: 369–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, Michael A., and Michael T. Putnam. 2019. Language membership as a gradient emergent feature. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 22: 701–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayne, Richard S. 2005. Movement and Silence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keiser, Steven H. 2001. Language Change across Speech Islands: The Emergence of a Midwestern Dialect of Pennsylvania German. Ph.D. thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Keiser, Steven H. 2012. Pennsylvania German in the American Midwest. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knodt, Thomas. 1986. Quantitative aspects of lexical borrowing into Pennsylvania German. In Studies on the Languages and Verbal Behavior of the Pennsylvania Germans I. Edited by Werner Enninger. Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag, pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Ruth. 2016. A split analysis of plurality: Number in Amharic. Linguistic Inquiry 47: 527–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, Judith F., and Tamar H. Gollan. 2014. Speech planning in two languages: What bilinguals tell us about language production. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Production. Edited by Matthew Goldrick, Victor Ferreira and Michele Miozzo. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lohndal, Terje, and Michael T. Putnam. 2021. A tale of two lexicons: Decomposing complexity across a distributed lexicon. Heritage Language Journal 18: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Luis. 2020. Bilingual Grammar: Towards an Integrated Model. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Louden, Mark L. 1989. Bilingualism and Syntactic Change in Pennsylvania German. Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Louden, Mark L. 2016. Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. Baltimore: John Hopkins. [Google Scholar]

- Louden, Mark L. 2020. Minority Germanic languages. In The Cambridge Handbook of Germanic Linguistics. Edited by B. Richard Page and Michael T. Putnam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 807–32. [Google Scholar]

- Louden, Mark L., and B. Richard Page. 2005. Stable bilingualism and phonological (non)convergence in Pennsylvania German. In ISB4 Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism. Edited by James Cohen, Kara T. McAlister, Kellie Rolstad and Jeff MacSwan. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 1384–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstamm, Jean. 2008. On little n, √, and types of nouns. In Sounds of Silence: Empty Elements in Syntax and Phonology. Edited by Jutta Hartmann, Veronika Hegedus and Henk van Riemsdijk. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 105–43. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 2013. Locality domains for contextual allomorphy across the interfaces. In Distributed Morphology Today. Edited by Ora Matushansky and Alec Marantz. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, Virorica, and Michael Spivey. 2003. Competing activation in bilingual language processing: Within-and between-language competition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 6: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, Éric. 2012. Flavors of division. Linguistic Inquiry 43: 650–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, Éric. 2014. Many a plural. In Weak Referentiality. Edited by Ana Aguilar-Guevara, Bert Le Bruyn and Joost Zwarts. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 157–81. [Google Scholar]

- Matras, Yaron. 2009. Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matras, Yaron. 2014. Why is borrowing of inflectional morphology dispreferred? In Borrowed Morphology. Edited by Francesco Gardani, Peter Arkadiev and Nino Amiridze. Berlin: Mouton, pp. 41–80. [Google Scholar]

- Meister Ferré, Barbara. 1994. Stability and Change in the Pennsylvania German Dialect of an Old Order Amish Community in Lancaster County. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, Heather. 2017. Nested phase interpretation and the PIC. In The Structure of the Words at the Interfaces. Edited by Heather Newell, Máire Noonan, Glyne Piggott and Lisa deMena Travis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 20–40. [Google Scholar]

- Page, B. Richard. 2011. Gender assignment of English loanwords in Pennsylvania German: Is there a feminine tendency? In Studies on German-Language Islands. Edited by Michael T. Putnam. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 151–63. [Google Scholar]

- Paster, Mary. 2014. Allomorphy. In The Oxford Handbook of Derivational Morphology. Edited by Rochelle Lieber and Pavol Štekauer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 219–34. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2018. Heritage Languages and Their Speakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Michael T. 2020. One Feature—One Head: Features as functional heads in language acquisition and attrition. In New Trends in Language Acquisition within the Generative Perspective. Edited by Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes and Cristina Suárez-Gómez. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Michael T., Matthew Carlson, and David Reitter. 2018. Integrated, not isolated: Defining typological proximity in an integrated multilingual architecture. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramchand, Gillian. 2019. Event structure and verbal decomposition. In Oxford Handbook of Event Structure. Edited by Robert Truswell. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 314–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand, Gillian, and Peter Svenonius. 2014. Deriving the functional hierarchy. Language Sciences 46: 152–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reed, Carroll E. 1942. The gender of English loan words in Pennsylvania German. American Speech 17: 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Carroll E. 1948. The adaptation of English to Pennsylvania German morphology. American Speech 23: 239–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Carroll E., and Lester W. J. Seifert. 1954. A Linguistic Atlas of Pennsylvania German. Marburg: Becker. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, Elizabeth. 1992. Cross-linguistic evidence for Number Phrase. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 37: 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmons, Joseph. 2018. A History of German: What the Past Reveals about Today’s Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann, Katharina S., and Michael T. Putnam. 2021. Relativized prosodic domains: A late-insertion account of German plural allomorphy. Languages 6: 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmann, Katharina S., and Laura C. Smith. 2022. Practical prosody: New hope for teaching German plurals. Unterrichtspraxis/Teaching German 55. [Google Scholar]

- Scontras, Gregory. 2022. On the semantics of number morphology. Linguistics and Philosophy Online. , 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scontras, Gregory, Maria Polinsky, and Zuzanna Fuchs. 2018. In support of representational economy: Agreement in heritage Spanish. Glossa 3: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seifart, Frank. 2012. The principle of morphosyntactic subsystem integrity in language contact: Evidence from morphological borrowing in Resígaro (Arawakan). Diachronica 29: 471–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Laura Catharine. 2020. The role of foot structure in Germanic. In The Cambridge Handbook of Germanic Linguistics. Edited by Michael T. Putnam and B. Richard Page. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenstuhl, Ingrid, Sonja Eisenbeiss, and Harald Clahsen. 1999. Morphological priming in the German mental lexicon. Cognition 72: 203–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Starke, Michel. 2009. Nanosyntax: A short primer to a new approach to language. Nordlyd 36: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Starke, Michal. 2014. Towards an elegant solution to language variation: Variation reduces to the size or lexically stored trees. In Linguistic Variation in the Minimalist Framework. Edited by M. Carme Picalo. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 140–53. [Google Scholar]

- Stroik, Thomas S., and Michael T. Putnam. 2013. The Structural Design of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Svenonius, Peter. 2010. Spatial P in English. In Mapping Spatial PPs: The Cartography of Syntactic Structure. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque and Luigi Rizzi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 127–60. [Google Scholar]

- Svenonius, Peter. 2020. A span is a thing: A span-based theory of words. In Proceedings of NELS 50—Volume 3. Edited by Mariam Asatryan, Yixiao Song and Ayana Whitmal. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Trommer, Jochen. 2021. The subsegmental structure of German pluralallomorphy. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 39: 601–56. [Google Scholar]

- van Coetsem, Frans. 1988. Loan Phonology and the Two Transfer Types in Language Contact. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ness, Silke. 1995. Ohio Amish women in the vanguard of a language change: Pennsylvania German in Ohio. American Speech 70: 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, Heide. 1999. Die Pluralbildung im Deutschen - ein Versuch im Rahmen der Optimalitätstheorie. Linguistik Online 4: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, Richard. 1996a. Phonological versus morphological rules: On German umlaut and ablaut. Journal of Linguistics 32: 113–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, Richard. 1996b. The Phonology of German. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, Richard. 2001. How prosody shapes German words and morphemes. Marburger Arbeiten zur Linguistik 5: 155–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, Richard. 2009. The grammar and typology of plural noun inflection in varieties of German. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 12: 137–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltschko, Martina. 2008. The syntax of non-inflectional plural marking. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26: 639–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltschko, Martina. 2014. The Universal Structure of Categories: Towards a Formal Typology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltschko, Martina. 2021. The syntax of number markers. In The Oxford Handbook of Grammatical Number. Edited by Patricia Cabredo Hofherr and Jenny Doetjes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 164–96. [Google Scholar]

- Winford, Donald. 2005. Contact-induced changes: Classification and processes. Diachronica 22: 373–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| {e} | Katz | Katz-e | ’cat-pl’ |

| {r} | Hemm | Hemm-r | ’shirt-pl’ |

| {n} | Leffli | Leffli-n | ’spoon-pl’ |

| {s} | Baller | Baller-s | ’ball-pl’ |

| {∅} | Frein | Frein-∅ | ’friend-pl’ |

| umlaut | Hand | Hend | ’hand-pl’ |

| umlaut-{r} | Haus | Heis-r | ‘house-pl’ |

| Singular | Plural | Process | |

|---|---|---|---|

| */messer/ | messer | messr-e | *Syncope |

| */hiwwel/ | hiwwel | hiwwl-e | |

| /messr/ | mess.r | messr-e | Liquid syllabification |

| /hiwwl/ | hiww.l | hiwwl-e | |

| /hemm/ | hemm | hemm.r |

| Exponent | Singular | Plural | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| {s} | Baller | Ballers | ball (pl) | |

| Frog | Frogs | frog (pl) | ||

| {e} | Katz | Katze | cat (pl) | |

| Hiwwel | Hiwwle | hill (pl) | ||

| {r} | Hemm | Hemmer | shirt (pl) | |

| Haus | Heiser | house (pl) | ||

| {∅} | Frein | Frein | friend (pl) | |

| Hand | Hend | hand(pl) |

| Singular L-Span | Plural L-Span | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | F1 | F2 | ||

| Baller | s | |||

| Frog | s | |||

| Hiwwl | e | |||

| Katz | e | |||

| Haus | Heis | r | ||

| Hemm | r | |||

| Frein | ||||

| Hand | Hend | |||

| Singular L-Span | Plural L-Span | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | F1 | F2 | ||

| Car | s | |||

| Ox | en | |||

| Child | Childr | en | ||

| Moose | ||||

| Mouse | Mice | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fisher, R.; Natvig, D.; Pretorius, E.; Putnam, M.T.; Schuhmann, K.S. Why Is Inflectional Morphology Difficult to Borrow?—Distributing and Lexicalizing Plural Allomorphy in Pennsylvania Dutch. Languages 2022, 7, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020086

Fisher R, Natvig D, Pretorius E, Putnam MT, Schuhmann KS. Why Is Inflectional Morphology Difficult to Borrow?—Distributing and Lexicalizing Plural Allomorphy in Pennsylvania Dutch. Languages. 2022; 7(2):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020086

Chicago/Turabian StyleFisher, Rose, David Natvig, Erin Pretorius, Michael T. Putnam, and Katharina S. Schuhmann. 2022. "Why Is Inflectional Morphology Difficult to Borrow?—Distributing and Lexicalizing Plural Allomorphy in Pennsylvania Dutch" Languages 7, no. 2: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020086

APA StyleFisher, R., Natvig, D., Pretorius, E., Putnam, M. T., & Schuhmann, K. S. (2022). Why Is Inflectional Morphology Difficult to Borrow?—Distributing and Lexicalizing Plural Allomorphy in Pennsylvania Dutch. Languages, 7(2), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020086