Abstract

The article argues that the alternation between the prepositions asce ‘from’ and an ‘from’ in the south Italian Greek variety Greko and a similar alternation between the preposition se ‘in, to, into’ and the allomorph s- found in both Greko and Standard Modern Greek represent instances of contextually conditioned allomorphy sensitive to a linearly adjacent definite article. Alternative approaches in terms of portmanteaux or making use of hyper-contextual rules for vocabulary insertion are shown to be unable to account for the data, supporting the need for allowing reference to linear adjacency relations in morphosyntactic theories of allomorphy.

1. Introduction

Based on alternations in the form of certain prepositions in varieties of Greek, this paper argues that accounts of contextually sensitive allomorphy need to be able to refer to relations of linear adjacency (Embick 2010, 2015; Christopoulos and Petrosino 2018; Felice 2021). The data discussed here thereby represent limits (or challenges) for recent attempts at reducing the need for linear relations in grammar (Moskal and Smith 2016). One relevant alternation pattern involves the two local prepositions asce and an, both meaning ‘from’, in the Greek variety Greko (glottocode aspr1238; Hammarström et al. 2021). Building on earlier observations by Rohlfs (1950, 1964), further supported by a small corpus study and enhanced with additional detail by elicited native speaker data, these prepositions are shown to be in an allomorphic relationship. The other pattern concerns the preposition se ‘in, into’ found in both Greko and Standard Modern Greek (SMG), which similarly alternates with a marked allomorph s-.

The analysis advocated here treats these alternations as instances of contextually conditioned allomorphy triggered by linearly adjacency to a definite article. I adopt a realisational perspective on the syntax–phonology interface along the lines of distributed morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993) where abstract syntactic heads are associated with phonological exponents only after syntactic structure has been built. The central observations regarding the patterns described in Section 3 and Section 4 should be accessible independently of this framework, but they may impact the way the generalisations are stated and are crucial to the theoretical discussion in Section 5.

Section 2 briefly presents the sources of the data used in this paper. Section 3 shows the complementary distribution of the Greko prepositions asce and an, suggesting that they are allomorphs with an occurring in the context of the definite article. Section 4 develops a parallel argument for the preposition se in Greko and SMG, with the allomorph s- being used with the definite article. In Section 5, I argue for an analysis that makes crucial use of linear adjacency, adopting Embick’s (2010) -LIN theory, after discussing problems arising for alternative analyses such as portmanteaux or using hyper-contextual rules for vocabulary insertion (Moskal and Smith 2016). The section also briefly points out a speculative alternative where the mechanism assembling complex heads would be sensitive to linear adjacency (van Riemsdijk 1998). Section 6 concludes.

2. Materials and Methods

Unattributed SMG data are based on the author’s personal knowledge and were verified with native speakers.

Greko is a highly endangered variety of Greek spoken by a small number of speakers in southern Calabria (Italy), as shown in Figure 1. Greko data presented without reference were elicited from two proficient native speakers of Greko. Both consultants also know SMG.

Figure 1.

Map indicating the approximate location of the speech areas of Greko and the Salentine Greek variety Griko (glottocode apul1237) in southern Italy. The map was generated using R (v. 4.2.0; R Core Team 2022) and RStudio (v. 2022.02.3; RStudio Team 2022) using the packages ggplot2 (v. 3.3.6; Wickham 2016) and ggmap (v. 3.0.0; Kahle and Wickham 2013). The script is available as supplementary material S2.

Additionally, a small corpus study was conducted on fables from the Bova variety of Greko collected in Crupi (1980, pp. 21–42; pp. 66–72). This collection consists of about 10,600 tokens. The text was made digitally searchable using optical character recognition1, and a student assistant created a list of sentences containing the target forms (an, azze, zze and asce) along with page reference, title of the fable, and the preceding sentence for context. I then manually annotated the hits to select those actually involving one of the target prepositions. This was necessary to accommodate for the fact that an is homophonous with a complementiser meaning ‘if’. Moreover, one instance of azze actually corresponded to an aorist form of the verb àsto ‘to kindle’.

3. The Distribution of asce and an

3.1. Etymology and Dialectal Variation

While the focus of this paper is not historical or dialectological, this section provides some context from the prior literature on Greko.

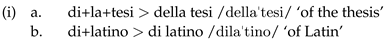

There is some diatopic variation in the phonological realisation of asce. The preposition is likely derived from the Classical Greek preposition ἐκ/ἐξ (Rohlfs 1964, pp. 148–50 and Karanastasis 1997, p. 116). As also described by Rohlfs (1964, p. 148), the variant in (1a) is associated with the varieties of Condofuri, Chorìo Roghudi, Roghudi, and Roccaforte/Vunì (and also of Gallicianò, not covered by Rohlfs), while (1b) is found in the variety of Bova. This reflects the general diatopic variation concerning how older ξ is resolved as either // (Bova) or /ʃ/ (most other varieties). Karanastasis (1997, p. 116) also lists the forms in (1d–f), with esce (1f) heading his discussion of the preposition and marked as Calabrian Greek (i.e., Greko), without further specification. The form zze (1c) is not specifically mentioned by Rohlfs (1964) or Karanastasis (1997) for Greko2, but Crupi (1980) contains several instances of it.

|

The forms asce and azze (1ab) seem to be the ones currently used by speakers of the respective dialects and are also employed in language teaching in current revitalisation efforts. The forms ssce and zze (1ef) are plausibly phonological reductions. I see no reason to not treat these forms as diatopic phonological variants of the same preposition, in line with the previous literature, with no difference concerning their respective relationship with an. Unless citing specific sources using a different form, in the following discussion I will refer to the preposition as asce for simplicity, as this is the form also commonly used by my consultants.

Turning to an, Karanastasis (1997, p. 115) suggests that this preposition derives from classical Greek ἀπὸ.3 Rohlfs (1964, p. 46, entry for ἀπὸ), on the other hand, explicitly rejects this etymology. Instead, he suggests a derivation from ἐκ/ἐξ (Rohlfs 1964, p. 149f.) via the varieties of asce discussed before (see also Rohlfs 1950, pp. 168–70). This is also reflective of his view of the relationship between asce and an as discussed in the next subsection.

While both asce and an generally express a source relationship and may be roughly translated as ‘from’. Some uses of asce are plausibly transfers from Italian (or Southern Calabrese) di, as in azze nista (Bova) ‘by night’, cf. Italian di notte (Rohlfs 1964, p. 149).

3.2. Evidence for an Allomorphic Relationship

The core observation concerning the distribution of an and asce has been reported by Rohlfs (1950, pp. 168–70) and Rohlfs (1964, p. 148f.). Rohlfs notes that asce is not used with definite articles in the complement of the preposition, while an is found before the definite article.4 This implies a complementary distribution of the two prepositions and, while not stated in those terms by Rohlfs, further suggests that they are allomorphs of the same underlying preposition.

The complementary distribution of an and asce/azze is corroborated by a corpus study based on the Greko texts in Crupi (1980, pp. 21–42; pp. 66–72). Recall that this text collection is based on the Bova variety, accounting for the prevalence of (a)zze over the variant asce in this dataset. Table 1 presents for each occurrence of the prepositions an, azze, zze, and asce whether it is followed by a definite article. The distribution is in line with Rohlfs’ prediction, with the preposition an always followed by a definite article and none of the other prepositions directly preceding a definite article. See supplementary material S1.

Table 1.

Counts of prepositions with/without immediately following definite article.

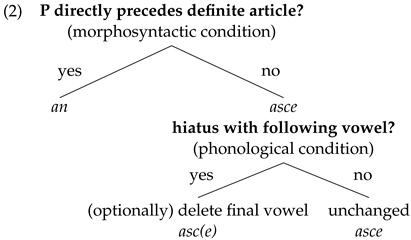

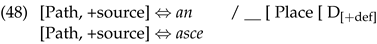

In the remainder of this section, I illustrate the distribution of asce and an and provide new data that help to clarify that the default form of the preposition is asce and that only when the preposition directly precedes a definite article is the marked allomorph an used. Notice also that there is an optional but common phonological process of hiatus avoidance that may reduce the final vowel of asce in front of a word beginning with a vowel. I will point out some relevant examples below, but this process becomes more important when discussing the less transparent behaviour of the preposition se in Section 4. The overall pattern is schematically illustrated in (2).

|

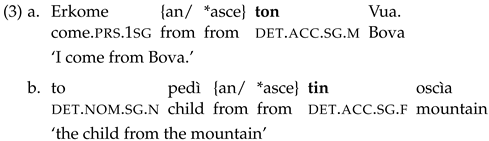

The examples in (3) illustrate the basic pattern where the use of an is required before the definite article, while asce would be deviant.5 This holds independently of whether the PP occurs in a verb or noun phrase or whether the complement of the preposition is a proper (place) name or a common noun.6

|

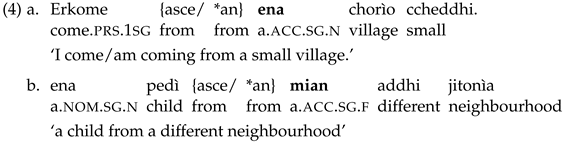

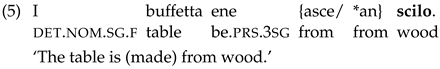

The examples in (4) and (5) illustrate the need to use asce in the absence of a definite article. Again, this happens independently of whether the PP is a verbal argument (4a), a nominal modifier 4b, or part of a clausal predicate (5). The examples also show that asce occurs with indefinite articles (4) as well as bare nouns (5).

|

|

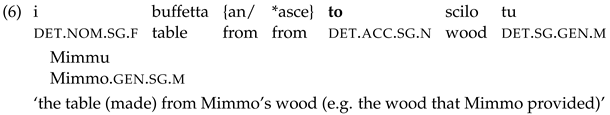

While asce has a non-local meaning in (5), indicating the material of the table, this non-local meaning is not exclusive to asce. As shown in (6), an can be used with the same interpretation. In line with an allomorphic analysis of the two forms, the crucial factor determining the use of asce or an is not any special interpretation, which might indicate that asce and an represent two distinct prepositions after all, but simply the absence (5) or presence (6) of the definite article.

|

Asce (or azze) must also be used in the context of personal pronouns as in example (7) from Crupi (1980). Since personal pronouns are generally considered to be definite, this illustrates that semantic definiteness of the complement of the preposition is not a sufficient condition for triggering the use of an.

|

| (Crupi 1980, p. 38, ‘To próvato ácharo curemmeno’) |

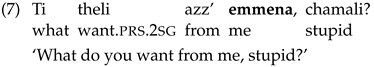

This example also illustrates the possibility of phonological reduction of the final vowel of asce/azze for hiatus avoidance mentioned in the schema in (2). The fact that an is not used in such contexts even though its CV syllable structure would also avoid hiatus suggests that the distribution of an is not phonologically motivated (at least not synchronically).

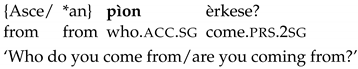

Note that Rohlfs (1950) mentions that an can also be used in one context without a definite article, namely with the wh-pronoun tinon ‘who.acc.sg’ in (8a). My consultants, however, were not familiar at all with this formulation, insisting on a formulation along the lines of (8b) instead, requiring the use of asce.

| (8) | a. |  | |

| ‘Who do you come from/are you coming from?’ | (Rohlfs 1950, p. 170) | ||

| b. |  |

Since Rohlfs’ data were collected in the first part of the twentieth century, it is feasible that an used to have a wider distribution than it has now. In any case, as far as I can tell only the definite article seems to license an in current usage.

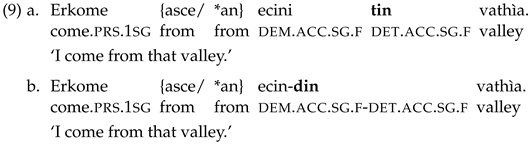

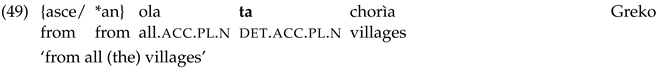

Importantly, the mere presence of a definite article is not sufficient for licensing the use of an. Similarly to SMG, demonstrative modifiers in Greko generally occur in combination with the definite article, although the demonstrative and article may contract into one phonological word in Greko, so that distal ecino to spiti ‘that house’ becomes ecindo spiti (Rohlfs 1950, pp. 114–18). This contraction is systematically possible also for the proximal (tuto to → tundo) and medial (ettuno to→ ettundo) demonstrative forms and for other -feature combinations (see example (9) and Rohlfs (1950, ibid.)).

Importantly for the current purposes, the definite article is separated from the preposition by the demonstrative in either case. As illustrated in (9), the source preposition needs to be asce in this case, regardless of whether the demonstrative and the determiner are contracted. Similar to example (7) above, the phonological process of hiatus avoidance mentioned in (2) may reduce the final vowel of asce in front of ecini/ecin-din.

|

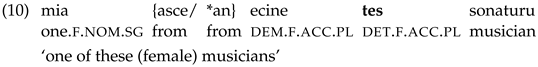

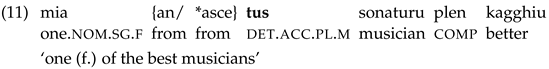

The form asce is also obligatory if the preposition precedes a demonstrative in a partitive constructions like (10). Example (11) illustrates that an has to be used in partitive constructions precisely when the preposition precedes the definite article. Again, the alternation shows up independently of the semantic contribution of the preposition.

|

|

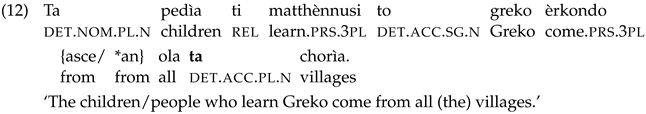

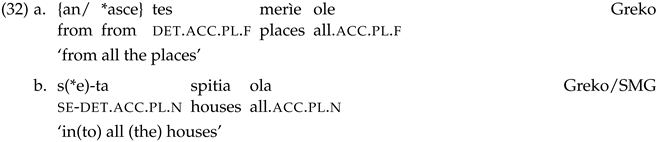

A similar effect is observed with the quantifier olo ‘all’, whose nominal complement needs to be definite. In combination with a preposition, this typically gives rise to a configuration where the quantifier intervenes between the preposition and the definite article. Again, only asce may be used here, and the use of an is deviant, as shown in (12).

|

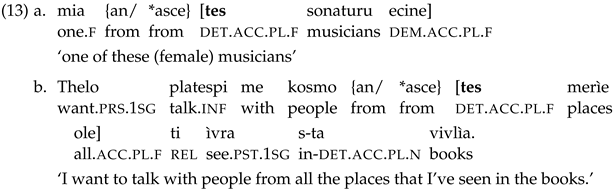

A look at alternative word orders shows that the intervention of the demonstrative or quantifier between the preposition and the definite article is crucial for the use of asce over an. Apart from the (unmarked) configuration where the demonstrative (9) or the quantifier olo (12) occur in noun phrase initial position, Greko—like SMG—allows an alternative word order where they appear postnominally. In the PPs under discussion, this leads to a configuration where the preposition directly precedes the definite article and only the preposition an is acceptable, as shown in (13).

|

Table 2.

Contexts for the use of an and asce.

Importantly, examples with demonstrative modifiers or the quantifier olo like those illustrated in (9)–(13) show that the mere presence of the definite article is not sufficient for triggering the use of the allomorph an. Instead, a local relationship needs to obtain between the preposition and the article, which I argue to be linear adjacency in more detail in Section 5. Before that, however, the next section discusses a similar alternation for the stative/allative preposition se found in both Greko and SMG.

4. Allomorphic Realisations of the Preposition se in SMG and Greko

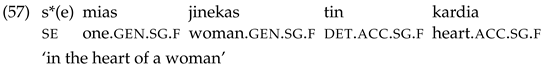

The allomorphic alternation of asce and an parallels the behaviour of the preposition se in both Greko and SMG that can be used as a stative locative preposition (‘in’) and a dynamic goal-directed preposition (‘to, into’; allative/illative). I mostly use SMG examples in this section, but the Greko patterns should be essentially parallel except for the possessor fronting construction discussed at the end of the section, which will provide additional insights into the behaviour of the alternation.

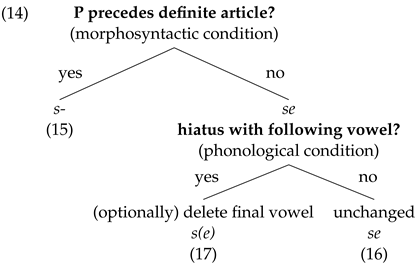

The preposition se has an allomorph s- that occurs and in fact phonologically combines with a directly following definite article (see also Holton et al. 2012, p. 53), thereby resembling Greko an. The hiatus avoidance mechanism described for Greko asce in the discussion of (2) also seems to apply to se. However, while the phonologically reduced form of asc(e) is clearly distinct from the morphosyntactically triggered marked allomorph an, in the case of se both the marked allomorph used before definite articles, represented here as s-, and the hiatus avoiding phonological reduction of the default form of the preposition, represented as s(e), are realised by the same surface form /s/. Their different role in the system is schematically illustrated in (14).

|

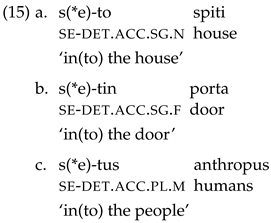

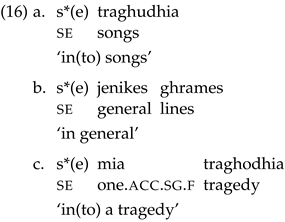

The use of the marked allomorph s- instead of default se is obligatory in front of a definite article, as shown by the examples in (15). In contrast, the examples in (16) illustrate the obligatory use of default, unreduced se directly before a noun, an adjectival modifier, and an indefinite article (i.e., in contexts without a following definite article).

|

|

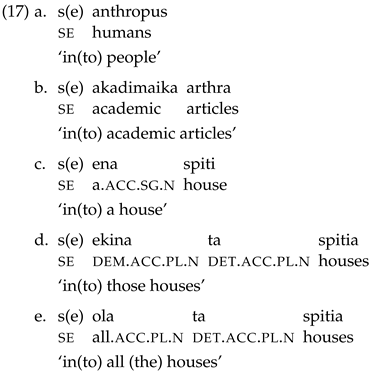

The second type of the reduced form /s/ derived by the phonological process of hiatus avoidance (i.e., when se precedes a vowel-initial word) is illustrated in (17).

|

Crucially, this phonological process is not mandatory and the non-reduced form may be used in careful speech in these cases. Underlyingly, all these examples employ the default allomorph se, not the allomorph s-. The optional availability of the full form se can therefore serve as a diagnostic for whether an instance of reduced /s/ corresponds to the allomorph s- (no alternation with /se/ possible) or a phonologically reduced form of the default form se (alternation possible).

Examples (17de) are particularly noteworthy here, since it may look like the demonstrative ekina ‘that’ and the quantifier ola ‘all’ can be used with either se or s-. However, if we really dealt with the allomorph s- here, the unreduced form should be deviant just as in (15). The possibility of using both /se/ and /s/ indicates that the default allomorph se is employed here, as expected if s- can only be used directly before a definite article. This alternation therefore behaves in a parallel way to asce/an in the previous section.

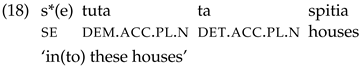

Apart from the demonstrative ekinos and the distance-neutral afta ‘these/those’, which behaves the same way, there is a further demonstrative tuta ‘these’. It is not very widely used, but is still recognised in SMG, and it is the regular proximal demonstrative in Greko. Since it does not begin with a vowel, the phonological trigger for the optionality of s(e) in the examples in (17) does not apply. Example (18) shows even more clearly that the configuration with a demonstrative intervening between the preposition and a definite article leads to the selection of the default allomorph se, as suggested in (14).

|

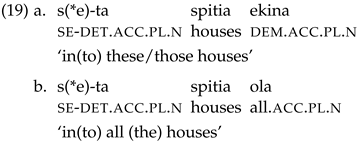

In configurations where the demonstrative or quantifier is postnominal (19), the phonological environment for hiatus is absent. Instead, the preposition directly precedes the determiner and is obligatorily realised as s-, showing that we are dealing with the morphosyntactically triggered allomorph.

|

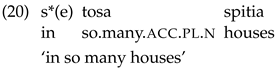

A simple observation shows that it is unlikely that phonological considerations, rather than morphosyntactic ones, trigger the use of s- in the context of the definite article. The first syllable of the quantifier tosa ‘so many.acc.pl.n’ is segmentally identical to the neuter accusative singular article to, while tosa minimally contrasts by requiring the use of se as shown in (20).7

|

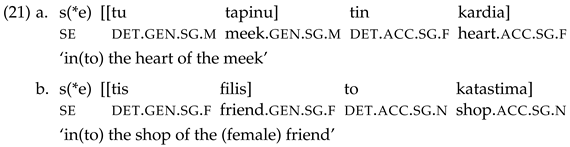

A final important observation comes from preposed genitives in SMG. In such configurations, which are stylistically marked but still productive, s- combines with the (genitive-marked) article of the possessor as shown in (21). This shows that the reduced form s- is obligatorily selected even when the following article is not the head of the complement DP of the preposition.8

|

I will return to these constructions in the next section.

5. Theoretical Accounts

In this section, I discuss potential theoretical analyses of the preposition alternation patterns, illustrating the crucial role of linear adjacency for adequately capturing the data. The approaches I address all adopt realisational, non-lexicalist models of grammar like distributed morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993; Marantz 1997) and similar frameworks, meaning that phonological content is inserted post-syntactically, that there is no separate generative component for “words”, and that syntactic structure extends “all the way down”.

The next subsection sketches some basic assumptions about the structure of spatial PPs. Section 5.2 summarises some core data illustrating the interaction of the prepositions with constructions with demonstrative modifiers, the quantifier olo ‘all’, and fronted genitives and presents the structural analyses assumed for these constructions. The alternations observed there serve as benchmarks to evaluate the different theoretical approaches. In Section 5.3, I discuss and reject the possibility that the marked forms of the prepositions occurring with the definite article may be analysed as portmanteaux of a definite article and the respective preposition. In Section 5.4, I argue for an account that treats the alternations as contextually conditioned allomorphy of the preposition and makes crucial reference to linear adjacency (Embick 2010), rejecting an alternative that eschews linear adjacency relations in favour of hyper-contextual rules for Vocabulary Elements (VEs) (Moskal and Smith 2016). Finally, Section 5.5 presents an argument against a potential phonological analysis of the se/s- alternation.

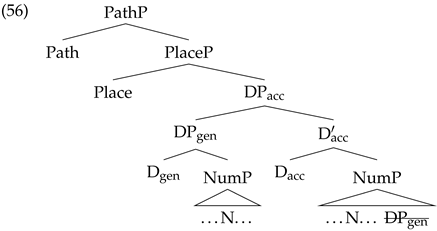

5.1. The Structure of Spatial PPs

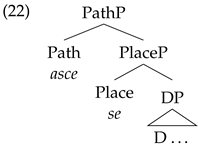

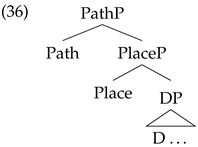

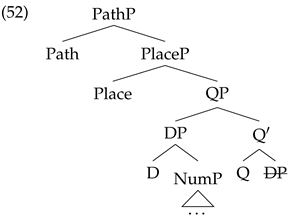

Dynamic prepositions like to or from are widely taken to structurally contain (at least) the stative locative (Asbury et al. 2008; Caha and Pantcheva 2020; den Dikken 2010; Pantcheva 2010; Radkevich 2010; Terzi 2010a; Zwarts 2017). A common implementation of these proposals is schematically illustrated in (22), employing the label Place for the stative and Path for the dynamic component. The respective loci associated with asce and se are indicated for illustration.

|

The fact that the prepositions asce/an and se/s- only overtly display one distinguishable piece of morphology may be addressed in at least two different ways in piece-based approaches to morphology: either by assuming null heads if Vocabulary Insertion (VI) can only take place at terminal nodes (Embick 2010, 2017) or by permitting the possibility that phonological material can realise larger chunks of structure, for instance phrases (Caha 2009, 2010; Pantcheva 2010; Starke 2009), spans (Merchant 2015; Svenonius 2012), or stretches (Ostrove 2018) of contiguous heads in an extended projection or through Radkevich’s (2010) vocabulary insertion principle.

In the former case, the Place head in (22) is silent when a source preposition like Greko asce/an ‘from’ realises Path (22).9 This is relevant to the interactions between prepositions and determiners discussed in the previous sections insofar as it means that D should be visible to the mechanism determining the allomorphy of asce and an in Path even though a (silent) Place head is structurally (and presumably linearly) intervening. One mechanism enabling such visibility is Embick’s (2010) pruning, which essentially allows silent heads to be ignored for the purpose of adjacency. I return to this issue in Section 5.4 when arguing that the allomorphy of the prepositions under discussion is indeed triggered by linear adjacency to the definite article.

Analyses permitting VI for non-terminal nodes (or spans/stretches of heads) can avoid the need for silent heads in (22) and hence also the need for a pruning-like mechanism, since in principle a Vocabulary Element (VE) like asce could simultaneously expone both the Path and Place nodes, effectively treating such prepositions as portmanteaux. This raises the further question of whether the observable interactions between prepositions and determiners could also be analysed as a portmanteau of the involved syntactic heads. I discuss and reject this possibility in Section 5.3.

5.2. Syntactic Structure of Crucial Configurations

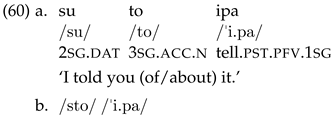

The variation in allomorph selection for asce/an and se/s- is particularly interesting in the presence of a demonstrative modifier, the quantifier olo, and with preposed genitives. Here, I present sketches of the relevant syntactic structures and briefly summarise relevant examples for reference in the later discussion.

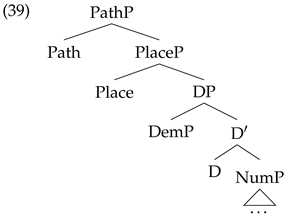

Demonstratives in Greek have been argued to be phrasal constituents occupying a specifier position in the extended nominal projection (Alexiadou et al. 2007; Choi 2014; Horrocks and Stavrou 1987; Panagiotidis 2000), typically SpecDP as shown in (23). The demonstrative has been suggested to be moved into SpecDP from a lower position inside the DP (Bernstein 1997; Brugè 1996, 2002; Giusti 1997, 2002; Panagiotidis 2000). An alternative perspective is that noun phrase initial demonstratives are heads taking DP as their complement as suggested by Julien (2005) for Scandinavian and sketched in (24).10 Both options will be briefly addressed in Section 5.3, although the choice between them will turn out to be insubstantial to the overall conclusion.

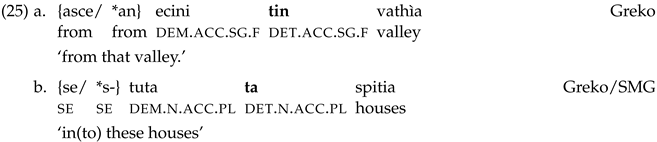

|

Configurations with a prenominal demonstrative require the use of the default forms asce and se for the two prepositions under discussion, as illustrated again in (25). The alternative postnominal configuration will be addressed shortly.

|

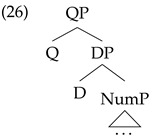

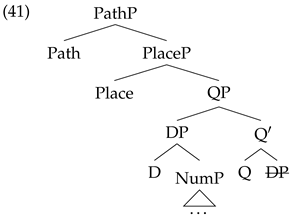

For the quantifier ola ‘all’ in its canonical noun phrase initial position, a QP structure like (26) with DP as complement of the quantifier is fairly uncontroversial.

|

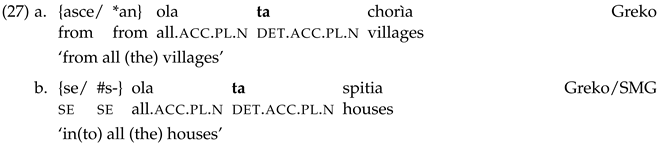

Like the prenominal demonstratives, the default forms of the prepositions need to be used with the quantifier in noun phrase initial position (27).11

|

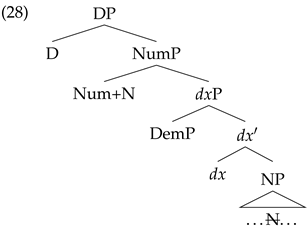

If demonstratives are base-generated in a lower position inside the DP (see references above), the demonstrative can be assumed to remain in a lower syntactic position with the noun raising to a higher position, for example to Num, as sketched in (28), loosely based on (Panagiotidis 2000). On this analysis, the demonstrative is assumed to be introduced in a low, deixis-related phrase (dxP) and remains in this lower position when used postnominally (instead of moving to SpecDP, which would derive the prenominal order).12

|

Julien (2005, ch. 4), on the other hand, suggests that postnominal demonstratives are derived by movement of the DP complement into SpecDemP as in (29). For the postnominal configuration of the quantifier olo, I assume that the complement DP moves to SpecQP as in (30), parallel to Julien’s (2005) treatment of postnominal demonstratives.

|

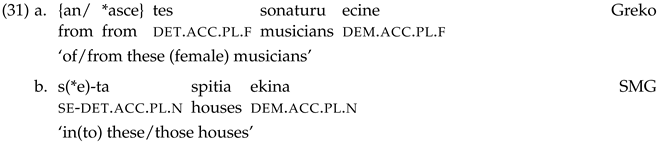

Recall that when the demonstrative or the quantifier does not occur at the beginning of the noun phrase, the marked forms an and s- need to be used (see (31) and (32)).

|

|

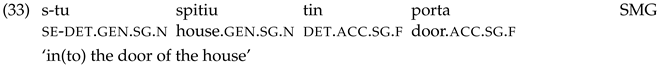

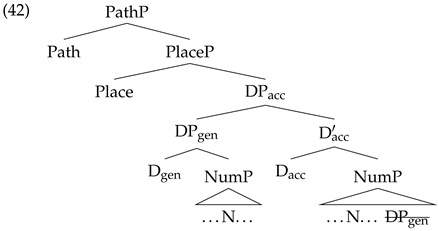

The same holds for the configuration with a preposed genitive in (33).

|

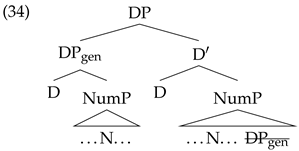

The structure of the prenominal genitives likely involves movement of the genitive DP from a lower position into SpecDP (Alexiadou et al. 2007) as shown in (34).

|

In the next subsections, I discuss how theoretical approaches to portmanteaux and allomorphy fare in accounting for these empirical patterns.

5.3. Analysing the P+D Interactions as Portmanteaux

A classic example of a portmanteau is French au (pl aux), which expones the combination of the preposition à ‘to’ and the masculine definite article (sg le, pl les), but is not decomposable into two distinct morphemes. For forms like sto ‘in(to) the’, decomposition into a preposition s- and a determiner to is much more straightforward. Matters are somewhat less clear when considering the relationship between the unmarked form of Greko asce ‘from’ and its combination with the definite article /to/ turning out as /'ando/ ‘from the’. Since the only common segment between the two forms is the initial /a/, it is not self-evident that a decompositional analysis like the one presented below in Section 5.4 is better than one where the preposition and determiner form a portmanteau, albeit a more transparent one than French au given the similarity of the sequence /do/ to the definite article. Indeed, the asce pattern seems (in-)transparent to a similar degree as German P+D combinations like vom ‘from the’ (von ‘from’ combined with dem ‘the.dat.sg.n/m’), which are sometimes described as portmanteaux (Schmerling 2019, ch. 5).

A reviewer asks for an example of a phenomenon where a portmanteau analysis is superior even when a decompositional analysis is possible. While I can offer no examples where a portmanteau analysis has been explicitly argued to be superior, there are certainly phenomena where decomposition may be possible, but is nonetheless contested. One such case concerns the Basque definite singular stative locative, e.g., mendi-an ‘on the mountain’. Superficially, the marker a-n could be decomposed into the definite article -a and a locative morpheme -n. However, there are strong arguments (e.g., distribution of epenthetic vowels; phonological effects of the definite article in dialects that do not apply in definite stative locatives) that the /a/ segment cannot be the definite article (Jacobsen 1977). Instead, there are competing analyses either analysing -a as a type of case marker (Etxepare 2013) or treating the sequence -an as a whole as exponent of the locative marker, with the definite article lacking overt exponence (Höhn 2014, pp. 151–53). For current purposes, the relevant point is that the veracity of (apparent) decomposability cannot always be determined a priori. I therefore take the possibility of a portmanteau analysis of the Greko and Greek P+D combinations seriously and use this subsection to show in some more detail why I consider it unsuitable.

The approaches to portmanteaux I address here are nanosyntax with phrasal spell-out (Caha 2009, 2010; Pantcheva 2010; Starke 2009), span-based analyses (along the lines of Merchant 2015; Svenonius 2012; Williams 2003), Ostrove’s (2018) alternative proposal of linear adjacency-based stretches, and Radkevich’s (2010) Vocabulary Insertion Principle (VIP). All these approaches purposely admit VI of non-terminal nodes in some form, which would also provide a means of avoiding the need for null heads in the complex internal structure of spatial adpositions, as mentioned in Section 5.1.13 Below, I show that their reliance on structural configurations between heads leads to wrong predictions for the phenomena at hand.

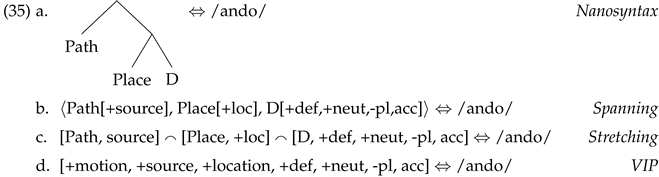

I cannot present the inner workings of the respective approaches in detail here, but below I briefly discuss how the possible VE for a P+D portmanteau in (35) would realise a basic structure like (36) in each of them.

|

|

Phrasal spell-out in nanosyntax would target a constituent containing all relevant heads of the adposition14 as well as the D head. The complement of D would be moved out of the way by the operation in (37), allowing the treelet in (35a) to match the remaining syntactic tree (ignoring movement traces).

| (37) | Spell-out-driven movement (Caha 2010, p. 59, (38); referring to 2009 class notes by Michal Starke) |

| If at a point of cyclic lexical access, a phrasal node can be spelled out only after the evacuation of a sub-constituent, then the constituent is marked for extraction. |

On a spanning account, the heads Path, Place, and D form a possible span because they are in a complementation/selection relation within the same (nominal) extended projection (Grimshaw 2005).15 This span of structurally adjacent heads can be realised by (35b). Ostrove’s (2018) stretching works in a similar way, but relies on the linear adjacency of the relevant heads within an extended projection, indicated here by ︵, rather than structural adjacency.

Finally, Radkevich’s (2010) VIP (38) requires all relevant heads (Path, Place, D) to be assembled by head movement into a complex head, which can then be realised by (35d). On standard assumptions, this resembles the other accounts insofar as the relevant heads need to be structurally adjacent to allow head movement, either due to the head movement constraint (Travis 1984) or relativised minimality (Rizzi 1990, 2001).

| (38) | Vocabulary insertion principle/VIP (Radkevich 2010, p. 8, (7)) |

| The phonological exponent of a vocabulary item is inserted at the minimal node dominating all the features for which the exponent is specified. |

I now turn to the wrong predictions a portmanteau analysis along those lines would make. Consider demonstrative modifiers first, on the classical analysis treating them as specifiers of DP (39).

|

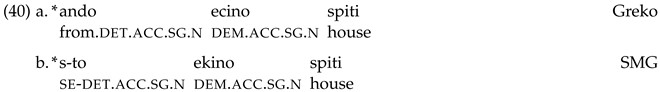

None of the above approaches to portmanteaux foresee the possibility that a phrasal constituent would interrupt the relationship between D and the higher adpositional heads. In a nanosyntactic treatment, the phrasal demonstrative would be moved out of the way by (37). Svenonius (2012, 1f.) explicitly shows that a phrase in SpecDP is not part of a span inside that DP. Ostrove’s (2018) stretches are similarly only defined across heads in an extended projection line. In a Radkevich (2010)-style account, a phrasal specifier should not block head movement from forming a complex head containing D, Place, and Path. This means that the relationship licensing the insertion of the respective VEs in (35) still obtains on each account, leading to the wrong prediction that a portmanteau form could be inserted in the presence of a prenominal demonstrative as in (40).16

|

One possible way around this issue could be to analyse Greko and SMG demonstratives as heads in the extended nominal projection. Then the demonstrative, now a head, intervenes between the determiner and the adpositional heads for the purpose of phrasal spell-out or span/stretch formation, so the VEs above are blocked from applying. Similarly, a series of head movement operations deriving a complex head containing D, Path, and Place would now also have to include the Dem head due to the head movement constraint, correctly blocking non-terminal insertion of (35d) on Radkevich’s (2010) VIP.

However, this analytical move would not be sufficient to prevent further empirical issues for a tentative portmanteau analysis of the prepositional alternations under discussion. Recall that the quantifier olo ‘all’ intervenes between a preposition and the definite article, leading to the use of unmarked prepositional forms asce or se, respectively, but that the marked form an or s- must be used when the quantifier is postnominal and the preposition is directly adjacent to the definite article. The tree in (41) repeats the structural configuration for the postnominal quantifier olo from Section 5.2.17

|

The three portmanteau approaches that do not make reference to linear order, nanosyntactic phrasal spell-out, spans, and Radkevich’s (2010) VIP, wrongly predict that the marked (tentative portmanteau) form should not be used here. There is no constituent in (41) containing only Path, Place, and D, so the nanosyntactic treelet (35a) cannot be inserted. Similarly, on the standard, complementation-based definition of spans there is no span ⟨Path, Place, D⟩ excluding Q. In addition, a head-movement operation from D to Place (and onwards) would violate the freezing condition, the ban on movement out of already moved constituents (e.g., Corver 2017; Ross 1967; see also Harizanov and Gribanova 2018, fn. 30), so the complex head required by the VE in (35d) could not be derived either.

Of the above accounts, only Ostrove’s (2018) stretches reference the linear order of the terminal nodes in an extended projection. Path, Place, and D are linearly adjacent in (41), and assuming that the head of the moved copy of DP still counts as part of the extended projection after movement, that configuration then corresponds to a stretch Path︵Place︵D, correctly predicting that a portmanteau could be realised along the lines of (35c).

Finally, the interaction of preposition allomorphy with the fronted genitive construction cannot be accounted for by any of the portmanteau analyses. Given the structural basis of all these accounts, the central issue is the fact that the preposition combines with the determiner of the genitive, not that of the possessee even though the latter is structurally closer. Consider the structure in (42). For easier distinction, the head of the genitive DP is marked D, and the head of the possessee/matrix DP D.

|

All portmanteau accounts under discussion falsely predict a portmanteau consisting of the preposition and the accusative determiner (i.e., the determiner of the matrix DP, as in (43)). As with the previous examples, this portmanteau is deviant regardless of whether it is realised in the base position of the preposition or the accusative determiner.

|

For a nanosyntactic account, there is no licit way to derive a constituent from (42) that contains only Path, Place, and D, but spell-out-driven movement of the genitive DP18 easily results in a constituent containing Path, Place, and D, leading to the wrong prediction. Spans and stretches are defined on the basis of extended projections, but the genitive DP is a distinct extended projection. Consequently, there is no span ⟨Path, Place, D⟩ or stretch [Path] ︵ [Place] ︵ [D] in (42). There is, however, a span ⟨Path, Place, D⟩ and a stretch [Path] ︵ [Place] ︵ [D], again wrongly predicting that (43) should be well formed. Concerning Radkevich’s (2010) VIP approach, the derivation would need to form a complex head containing D, Place, and Path from (42). On standard assumptions, it is not clear how or why D rather than D would undergo head movement to Place and then onward to Path. That more plausible movement of D would again lead to the wrong prediction in (43).

To sum up, all of the potential portmanteau analyses mentioned above run into empirical issues by falsely predicting that portmanteaux should be available across demonstrative modifiers (unless they are analysed as heads) and across a preposed genitive. Only one approach avoids wrongly excluding portmanteaux in configurations with postnominal uses of the quantifier olo ‘all’ as in (41), namely the account making use of Ostrove’s (2018) stretches. The common problem of all these approaches is that the domains where portmanteaux may be used are defined on a structural basis, either by constituency (phrasal spell-out), selection/extended projections (spans/stretches), or the restrictions on head movement (VIP). The reason stretches fare better for at least one of the problems mentioned is precisely because they also make reference to linear order. In the next section, I will show that an analysis with a stronger emphasis on linear adjacency can avoid all the wrong predictions discussed here.

I conclude that none of the presented portmanteau-based analyses provide a satisfactory analysis of the Greko and SMG preposition alternations. This does not preclude the possibility of a portmanteau-based analysis per se, but any such account would need to assign a more central role to linear adjacency than the discussed approaches allow.19 However, a portmanteau account modified in such a way may eventually not be very different from the type of allomorphy-based account advocated in the next section. At that point, the relatively straightforward decomposition of the tentative portmanteaux into a special form of the preposition and a regular form of the definite determiner would probably suggest an allomorphy-based account as the simpler option for the present phenomena.

5.4. Allomorphy and Adjacency

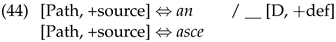

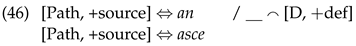

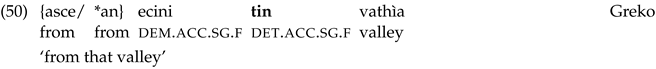

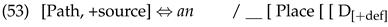

I now turn to analyses that treat the asce/an and se/s- alternations as instances of contextually conditioned allomorphy of the preposition. I have implicitly used this assumption to describe the patterns in Section 3 and Section 4. The VEs in (44) and (45) schematically formalise the idea that the marked form, an ‘from’ or s- respectively, is used in the context of the definite article.

|

|

The question is how the notion of context is restricted here, that is, which relation needs to obtain between the prepositional morpheme and the D head such that the latter can effect the choice of the marked allomorph of the preposition in exactly the right configurations. Accounts of allomorphy within the framework of distributed morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993) broadly agree that VI proceeds cyclically and that this results in certain structurally defined locality domains that restrict which other nodes are accessible as context for the VI of a given node (Bobaljik 2000, 2012; Embick 2010). Some authors posit further that linearly adjacency is another requirement for contextual allomorphy, that is, a node A is only accessible as context for VI of Node B if the two are linearly adjacent.

Here, I discuss whether an analysis of the preposition allomorphy presented above requires reference to linear adjacency or whether it is possible to dispense with it. I argue for an analysis along the lines of Embick’s (2010) -LIN theory, which takes linear adjacency to be a necessary requirement for triggering contextual allomorphy20, over Moskal and Smith’s (2016) proposal of hyper-contextual rules of VI. I begin by outlining how both approaches can formalise the allomorphy in the simple cases before turning to the more complex configurations discussed above for the portmanteau analyses.

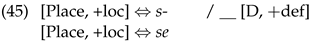

Embick (2010) uses the symbol ︵ to indicate concatenation of two elements, so the contextual condition for Greko an may be restated as in (46).

|

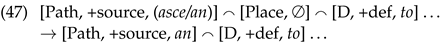

Importantly, Embick also proposes that nodes with null exponents may be removed or ‘pruned’ from linearisations, meaning that they do not count as linear interveners. This is important here because we have assumed that the structure of a dynamic preposition like asce ‘from’ contains a Path and a Place node. The Place node linearly (and structurally) intervenes between the Path node and D. However, on the assumption that Place has a null exponent, pruning leads to the necessary linear configuration for (46) to apply in the presence of a definite article, as shown in (47).

|

Moskal and Smith (2016) argue that a theory of allomorphy that relies solely on cyclic domains (or accessibility domains) as restrictor of contextually conditioned allomorphy is superior to a theory that additionally incorporates linear adjacency.21 They propose that VEs can have “hyper-contextual” conditions, “mak[ing] reference to multiple nodes in the structure” (Moskal and Smith 2016, p. 296, (1)), and that this mechanism can account for many cases of blocking typically explained by linear adjacency restrictions. Hyper-contextual restrictions are similar to Svenonius’s (2012) spans discussed above in that they refer to regions of contiguous nodes (see Moskal and Smith 2016, p. 307, fn. 13). While Moskal and Smith (2016) focus on outward-looking allomorphy, I assume that a VE for the allomorph an with inward-looking hyper-contextual restrictions may look as in (48).22

|

The Place node intervening between Path and D is part of the structural description of the context of application for the VE an. In contrast to Embick’s approach, it does not matter for the selection of the allomorph an whether or not Place has an overt realisation.

In configurations with the prenominal quantifier as in (49), both approaches make the right predictions.23

|

On Embick’s (2010) -LIN approach, Q linearly intervenes between Path and D. Since it is overt, it cannot be pruned, and the condition for the insertion of an is not met, since Path is not linearly adjacent to D, even after pruning. Therefore, Path is realised by the default form asce. Similarly, the hyper-contextual rule for an in (48) cannot apply because the structural description lacks the Q head.

Configurations with initial demonstrative modifier as in (50) behave completely parallel to the prenominal quantifier on either approach if the demonstrative is a head in the extended projection.

|

The linear approach also correctly predicts that an cannot be inserted either if the demonstrative is analysed as specifier. While Ostrove’s (2018) stretches discussed in the previous section only involve a linearisation of the heads of an extended projection, the -LIN account refers to the overall linearised structure, which arguably includes specifiers. It may be that the structural details inside a complex phrase in specifier position are not visible to a higher head for reasons of locality, especially if the phrasal specifier contains a cyclic node itself (which is probably not the case for a tentative phrasal demonstrative), but it is clear that the demonstrative interrupts the linear adjacency of Path and D, whether as head or phrase.

For the hyper-contextual approach, matters are less clear because Moskal and Smith (2016) focus on complex heads and do not discuss constructions involving specifiers. If the parallel to spans is taken seriously and the structural description of hyper-contextual rules can only refers to heads, the conditions for the insertion of an into Place would still be met with a phrasal demonstrative in SpecDP, leading to the wrong prediction that this allomorph must be used. If specifiers could be referenced in hyper-contextual rules, the false insertion of an could be avoided, since the description of the VE does not contain a demonstrative specifier. I have to leave this question open here.

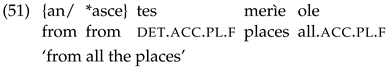

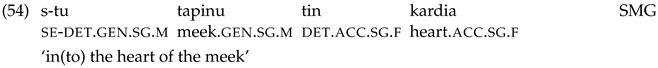

The postnominal quantifier configuration in (51) should trigger the use of the marked allomorph an. Recall that the structure is as in (52).

|

|

For the linear account, this is no problem from the perspective of adjacency, since Path is again linearly adjacent to D. An additional requirement from the perspective of cyclic locality is that the D head needs to be still accessible when Path undergoes VI. This should be the case even on the strong assumption that both D and Place are cyclic nodes (Embick 2010, p. 66, (66c)).

Matters look more problematic for the hyper-contextual approach. The structural context for insertion of the an allomorph is not available, since D is embedded in SpecQP. Even if specifiers can be referenced in hyper-contextual rules, a distinct homonym of the VE an would be necessary to allow insertion in Path, perhaps along the lines of (53). While technically possible, this would suggest that it is an accidental property of the vocabulary that the same form an is used with simple DPs and in constructions with postnominal quantifier olo.

|

The alternative account mentioned in note 23 where the quantifier is adjoined to DP would actually allow the Path head to access the determiner, which would make the correct prediction of inserting the marked allomorph here. However, as observed in note 23, the same prediction would, in this case wrongly, apply to the configuration with the prenominal quantifier.

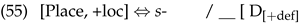

Even more serious issues arise for the combination of the preposition s- with the article of a preposed genitive in (54).

|

A VE like (55), which parallels the entry for an in (48) above, deals with simple cases correctly. However, based on the above considerations concerning the reference to specifiers in hyper-contextual rules, this rule predicts that the allomorph s- in (54) is triggered by D.

|

|

If this was the case, s- should be used independently of whether the fronted genitive contains a definite article. This is wrong, as shown in (57). Only the default form se is acceptable here.

|

A reviewer asks about configurations where the matrix DP is indefinite. If the determiner triggering the allomorphy was D, then the s- allomorph should not be available here. While such configurations as in (58) appear to be somewhat more marked, it is clear that the reduced form s- is obligatory here, again clearly indicating that the trigger is the linearly adjacent determiner of the possessor.

|

The only way to avoid these problems in an account with hyper-contextual rules (and without recourse to linear adjacency) would again be an additional VE for s- where the triggering context is a determiner in a following specifier. As before, even if the framework allowed the specific reference to heads of specifiers, the fact that the same allomorph s- occurs in these complex and the simple cases would be accidental. The generalisation that this allomorph occurs exactly when the preposition is adjacent to a definite article would be lost.

The linear/-LIN account deals with these data far more easily, since the marked form of the preposition is only inserted if a definite article is linearised adjacent to the preposition. The only additional requirement is that D be accessible in the spell-out cycle when Place or Path are inserted. Since the genitive is first merged inside the domain of D, the assumption that “the complement of a cyclic head x is not present in the PF cycle in which the next higher cyclic head y is spelled out” (Embick 2010, p. 54) may initially seem to cause problems if D and Place are indeed assumed to be cyclic nodes. In this case, merger of D would trigger spell-out for the cyclic domain of D in its low position, namely the complement of D, the head itself, and any non-cyclic material up to D. Upon merger of Place, the complement domain of D would be inaccessible.

However, just as the specifier of a phase head acts as an escape hatch for movement in the syntax, it seems plausible that the movement of DP to SpecDP may allow at least the edge of DP to be still accessible in the tentative cycle triggered if Place is a cyclic node. Alternatively, of course, it may be that Place is simply not a cyclic node.24

To sum up the discussion so far, for the empirical domain under discussion it seems that the linear component of Embick’s (2010) -LIN theory has an important role to play for understanding the allomorphy of asce/an and se/s-. Moskal and Smith’s (2016) hyper-contextual rules run into several problems, suggesting that they may not represent the best way of analysing this type of allomorphy. This is not necessarily a problem for the proposal of hyper-contextual rules per se though, since while Moskal and Smith (2016) aim at removing the need for linear adjacency from the theory, their specific claim is restricted to linear adjacency not being a universal restrictor on allomorphy (Moskal and Smith 2016, p. 311, fn. 14), admitting the possibility that linear adjacency may be necessary in specific instances. The present dataset seems to represent such an instance.

I have assumed here that the contextual restrictions can apply directly in the syntactic structure without first assembling the relevant nodes into M-words (Embick and Noyer 2001) (e.g., by means of head movement). While I think this is a plausible approach if we take seriously the insight that there is no coherent notion of word beyond, maybe, phonology (Marantz 1997; see also Newell 2009 and Kremers 2015), I briefly address the possible hypothesis that allomorphy can only be triggered within an M-word.

In fact, since the problems for the hyper-contextual account stem largely from the treatment of phrasal constituents, M-Word formation as a precondition for allomorphy triggering might make this account more successful. Assuming that M-Word formation proceeds by head movement, an account that aims to ensure that in all cases where the marked allomorph of the adpositions is inserted there is an M-word consisting (at least) of the relevant adpositions and the determiner raises the same issues as a portmanteau-based account along the lines of Radkevich’s (2010) VIP in Section 5.3.

As we saw there, the problematic configurations are those where the head movement operation would have to relate two head positions that are not in a selection relation. In this context, van Riemsdijk (1998) is worthy of note. In a discussion of preposition-determiner portmanteaux in German he suggests that a particular type of head movement, head adjunction (59), requires linear adjacency between the two lexical heads.

| (59) | Head adjunction (van Riemsdijk 1998, p. 645, (10a)) |

| Two phonetically identified (i.e., not silent) heads are joined, yielding an adjunction structure, in which case the two heads must be strictly linearly adjacent at the moment of application of the rule. |

This implementation is not directly compatible with a realisational model like distributed morphology, since a restriction to “phonologically identified heads” for a type of syntactic movement cannot be formulated in a model where functional heads systematically lack phonological content until post-syntactic vocabulary insertion takes place. The only operation with a similar linear adjacency requirement in DM is local dislocation (Embick and Noyer 2001), but this can only modify the linear order of nodes after VI and is not able to build M-Word structures. Nevertheless, it seems to me that an account aiming to involve head movement in the explanation of the preposition allomorphy patterns discussed in this paper would have to integrate some type of linear adjacency condition as in (59). With this in place, a portmanteau-based approach building on Radkevich (2010) might become feasible, as noted at the end of Section 5.3.

The central insight seems to be that an account of the preposition allomorphy discussed here cannot avoid admitting a role for linear adjacency in the grammar, either in the contextual conditions of VEs or in a special type of head movement operation for the formation of complex heads.

5.5. A Note on Phonology

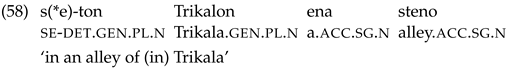

In this final section, I briefly address a potential argument that the allomorphy discussed above might actually be conditioned by phonological properties of the definite article rather than its morphosyntactic features.

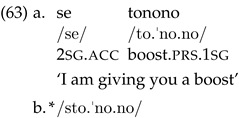

A phenomenon resembling the alternation for se/s- is the contraction of the second person singular dative clitic su with a following third person accusative clitic, most typically with neuter singular to or plural ta.25 This is illustrated in (60b), which alternates with the uncontracted version in (60a). If the defective prosodic status of the clitic pronouns plays a role in licensing the elision of the final vowel of the dative pronoun su in (60b), maybe the preposition se interacts in similar ways with the definite article, which is homophonous with the third person neuter accusative clitic pronouns.

|

While such considerations may have played a role in the genesis of the allomorphy of se/s-, I believe that, synchronically, the contraction in (60) should be treated as a distinct phenomenon.26

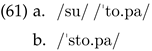

The first argument against unifying the two phenomena is slightly more complicated. Apart from (60b), there are further contraction patterns for the phrase in (60a). The accusative clitic can also contract with the verb for hiatus avoidance, leading to deletion of the initial vowel of the verb and stress shift onto the clitic as in (61a). Presumably the contracted form /'to.pa/ ‘I said it’ is not prosodically defective as it can also be used independently in other contexts. Nevertheless, the second person dative clitic can contract with this already contracted form as in (61b).

|

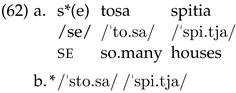

The final observation is notable because it suggests that it is not a requirement for the deletion of the final vowel on su that the following element be prosodically weak. If su-contraction and the contraction of the preposition se with the definite article were due to the same purely phonological mechanism, it would not be clear why (61b) is well-formed, but (62b) is not, even though /'to.pa/ ‘I said it’ and /'to.sa/ ‘so many’ share the same prosodic surface structure.

|

One way of addressing this contrast may be to assume that proclitics can interact with each other and a following verb form precisely because they form a prosodic unit. If the deletion can only be triggered within a prosodic unit (e.g., the prosodic word) and if we further assume that a preposition like se cannot form the relevant prosodic unit with a quantifier like tosa (but only with a definite article), this might capture the ungrammaticality of (62b).

However, even then, the parallel does not seem to carry over straightforwardly to se. The preposition se is homophonous with the second person singular accusative clitic se. Like other clitic pronouns in Greek (and Greko), se forms a prosodic unit with the verb it is an argument of. However, contraction of se is not possible, even if the first part of the verb is segmentally identical to a form of the definite article.

|

To sum up, the phonological phenomena addressed in this subsection generally apply optionally, whereas the choice of an and s- in the context of the definite article is not optional at all. Consequently, it seems plausible that they should be kept distinct. While I am not excluding the possibility that a refined analysis is possible, where the weak prosodic properties of the definite article rather than a morphosyntactic feature like [+def] trigger the allomorphy of asce/an and se/s-, I see no strong reason for a synchronic analysis to prefer an analysis in terms of phonologically conditioned allomorphy to the morphosyntactic one given in the above discussion. In any case, even an implementation in terms of phonologically conditioned allomorphy would likely remain very similar to the account based on Embick (2010) in the previous section, in that the marked allomorph would be triggered by linear adjacency to the relevant weak prosodic constituent.

6. Conclusions

Confirming and extending upon insights by Rohlfs (1950, 1964), I have argued that the Greko preposition an ‘from’ is an allomorph of the preposition asce ‘from’, triggered when a source preposition occurs in the local context of a definite article. I have further claimed that this finds a parallel in a similar alternation for the preposition se ‘in, into, to’ in both Greko and SMG, which occurs as s- in the context of definite articles.

Based on a discussion of several potential approaches to the Greko and SMG data, I have argued that linear adjacency plays an important role for any account of the phenomenon. More generally, the findings suggest that at least one of the claims in (64) holds, providing a challenge for attempts to avoid reference to linear adjacency in locality statements for morphological processes (Moskal and Smith 2016).

| (64) | a. | Contextually conditioned allomorphy may impose linear adjacency requirements on the triggering context. |

| b. | There is an operation for the formation of complex heads that involves a linear adjacency requirement (van Riemsdijk 1998). |

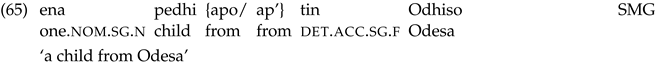

Stavros Skopeteas (p.c.) calls my attention to the alternation of SMG apo ‘from’ with the contracted form ap’, which closely resembles the distribution of the marked form s- above, since it can be used before vowels (hiatus avoidance), but also before the definite article (65).

|

However, (65) also shows that the choice of ap’ before the definite article is optional, in clear contrast to the mandatory use of the marked forms s-/an in front of definite articles. Therefore, the distribution is not categorical, suggesting that an allomorphic analysis along the lines suggested above is not directly applicable. A competing grammars approach (Pak 2016, pp. 20–22) might offer an account for this non-complementary distribution, with one grammar containing two competing allomorphs for the source preposition (as suggested above for asce/an and se/s-) and one only using the VE apo. Future research may investigate whether this distribution is stable or whether there are indications (e.g., from behavioural/corpus data) for a shift towards the type of clear allomorphic pattern discussed in this paper.

Finally, I am thankful to an anonymous reviewer for pointing out that while linear adjacency also matters for the English wanna contraction (cf. a.o. Lakoff 1970; Postal and Pullum 1982; Falk 2007), it contrasts with the phenomena discussed here insofar as it seems to be blocked by intervening null elements in the form of movement traces (66). More strikingly, while an embedded definite article in a preposed possessor can trigger preposition allomorphy (21), the wanna contraction cannot take place if to is contained in a more deeply embedded structure as shown by the deviance of (67b).

| (66) | a. | Who do you want (who) to kiss you? | |

| b. | *Who do you wanna kiss you? | (after Postal and Pullum 1982, p. 122, (1/2)) |

| (67) | a. | ?I don’t want [[to flagellate oneself in public] to become standard practice in this monastery]. |

| b. | *I don’t wanna flagellate oneself in public to become standard practice in this monastery. (after Postal and Pullum 1982, p. 124, (3bc)) |

A more detailed investigation of the differences between these phenomena and their theoretical implications presents a fruitful field for future research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/languages7030169/s1. Data Set S1: Categorised results of semi-manual corpus search for an, azze, zze, asce in Crupi (1980), in two formats (Crupi1980-finaldata.csv, Crupi1980-finaldata.xlsx); R script S2: Script for generating Figure 1, (S2-GrekoGrikomap.R).

Funding

The APC was funded by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all consultants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Elicited language data is contained within the article and the data collected for the corpus study of Crupi (1980) is available in the supplementary material. The data may be used freely with proper reference to this article and, when referring to the corpus data, to Crupi (1980).

Acknowledgments

Arringratsieguo an tin kardìa mu tin M. Olimpia Squillaci, ton Salvino Nucera ce ton Freedom Pentimalli ja to afùdima to me to Greko. I am also very thankful to Eleana Nikiforidou and Stavros Skopeteas for discussion of the SMG data and to Stavros Skopeteas and Götz Keydana as well as to four anonymous Languages reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions that greatly helped me to improve the article. Thanks also to Jan Kraaz for initial processing of the data from Crupi (1980). All remaining errors and shortcomings are my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

acc = accusative, comp = complementizer, dat = dative, dem = demonstrative, det = determiner, f = feminine, gen = genitive, inf = infinitive, m = masculine, n = neuter, nom = nominative, pfv = perfective, pl = plural, prs = present, pst = past, rel = relative, sg = singular, smg = Standard Modern Greek, ve = Vocabulary Element, vi = Vocabulary Insertion, vip = Vocabulary Insertion Principle.

Notes

| 1 | The software ocrmypdf (https://github.com/ocrmypdf/OCRmyPDF, accessed on 19 December 2021) was used with the Italian language package. | |

| 2 | Karanastasis (1997, p. 116) mentions the form only for varieties of Salentine Greek, i.e., Griko. | |

| 3 | Anecdotally observed treatments of the prepositions asce and an in current Greko teaching practice as distinct (unrelated?) prepositions—rather than as allomorphs—may be reflective of this perspective of two different sources. | |

| 4 | An anonymous reviewer points out that this alternation closely parallels the alternation between di and de in Italian. | |

| 5 | Note that voiceless stop in the onset of the definite article regularly undergoes voice assimilation after a preceding nasal, a common sandhi effect in Greko applying also after an. In (68a), for instance, the definite article is pronounced with a voiced onset leading to a realisation of the preposition + determiner string as /andon/. Rohlfs (1950, 1964) generally writes these voice assimilated and contracted forms and so do some speakers. My notation of the examples follows the current practice in revitalisation efforts aiming for a standardised orthography, which retains the initial t-grapheme of the article. | |

| 6 | While nouns and adjectives generally inflect for case, number, and gender in both Greko and SMG, in most examples I gloss these features only on determiners for better readability and because my focus is not on nominal inflection here. An exception is made for certain examples involving genitives. | |

| 7 | See Michelioudakis (2011, 100f.) for similar observations and examples. | |

| 8 | Preposed genitives do not seem to be productively available in Greko, so this particular alternation does not apply there. While a consultant initially seemed to accept a simple preposed genitive construction, all further examples were rejected—particularly those where the genitive construction was the complement of a preposition. | |

| 9 | In a similar vein, Terzi (2010b) suggests that Greek se ‘in, to, into’ realises the Place head and that its ambiguity between a stative locative meaning (‘in’) and a dynamic goal-oriented one (‘to, into’) is due to the potential presence of a silent Path projection. | |

| 10 | See Stavrou (1995) and Höhn (2016) for similar structures for adnominal pronoun constructions like emis i fitites ‘we students’ in SMG. Notice also that there are proposals in the literature that demonstratives may differ between and within languages concerning their status as phrase or head (Dékány 2011; Sybesma and Sio 2008), which to me seems the most plausible approach. For Greek varieties see also Guardiano and Michelioudakis (2019). | |

| 11 | While s(e) may be reduced to /s/ in (68b), this is due to hiatus avoidance as discussed in Section 4. The notation #s- indicates that the reduced form cannot be the marked allomorph. | |

| 12 | While this is most naturally accommodated when assuming that demonstratives are specifiers, a similar analysis is possible if prenominal demonstratives are treated as heads (see also Bernstein 1997). | |

| 13 | However, see Embick (2010, pp. 87–91) for relevant discussion concerning the French P+D portmanteau au in a framework that is restricted to terminal spell-out, but permits fusion of terminal nodes (Halle and Marantz 1993). | |

| 14 | On the assumption that each feature projects a head, the structure would actually be somewhat more complex than (67). At least, there would be an additional Source projection on top of Path following Pantcheva (2010), but the present simplification suffices for illustration of the principle. | |

| 15 | Like Grimshaw (2005), Svenonius’s (2012) spanning analysis of French au also has to treat adpositions as part of the extended nominal projection. | |

| 16 | It does not matter whether the P+D portmanteau is realised before or after the demonstrative, since the use of the portmanteau is deviant anyway. | |

| 17 | If one adopts the head-analysis for demonstratives just mentioned, the considerations below apply to postnominal demonstratives as well. An alternative analysis, mentioned by a reviewer, where the quantifier is adjoined, would avoid the issues mentioned below for the postnominal quantifier configuration, but the prenominal configuration would raise the same problems as those discussed above for a phrasal analysis of the demonstratives (i.e., the prenominal quantifier would falsely fail to prevent occurrence of the marked preposition allomorph). | |

| 18 | Alternatively, the assumption that this DP is already fully spelled out and is therefore ignored for phrasal spell-out (Caha 2009, p. 67, (27)). | |

| 19 | van Riemsdijk’s (1998) non-standard head adjacency operation mentioned at the end of Section 5.4 provides a version of head movement restricted by linear adjacency, which could potentially provide the basis for a portmanteau account building on Radkevich’s (2010) VIP. | |

| 20 | See also Embick (2015), Christopoulos and Petrosino (2018), and Felice (2021). | |

| 21 | See also Moskal (2015a, 2015b) and Smith et al. (2019). | |

| 22 | The open square brackets indicate levels of structure, following the practice of Moskal and Smith (2016), although they generally use closing brackets due to their focus on outward-looking allomorphy. | |

| 23 | A reviewer alludes to tentative alternative analysis where the quantifier is adjoined in order to facilitate the alternation with the postnominal position. This would raise a problem for the hyper-contextual account, since an adjunct should not influence the accessibility of the D head, wrongly predicting that the marked allomorph should be used. The -LIN approach would only run into issues if adjuncts are assumed to be inserted so late that the tentative adjoined quantifier would not be visible when the preposition undergoes VI. | |

| 24 | While D is a plausible candidate as a cyclic node given that it has also often been considered to be a phase head in the sense of Chomsky (2001), it is less clear if Place (or P) needs to be a cyclic node (Embick 2010, pp. 89–91). I do not aim to give a full account of cyclic domains here, the discussion simply serves to illustrate that issues beyond adjacency also come into play here. | |

| 25 | Thanks to Stavros Skopeteas for pointing out the similarity of these data. | |

| 26 | An anonymous reviewer points out the Italian data in (i), which display the di/de alternation in an otherwise identical immediate segmental and prosodic context, suggesting that there, too, the definite article is the relevant factor rather than phonological factors.

|

References

- Alexiadou, Artemis, Liliane Haegeman, and Melita Stavrou. 2007. Noun Phrase in the Generative Perspective. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbury, Anna, Jakub Dotlačil, Berit Gehrke, and Rick Nouwen, eds. 2008. Syntax and Semantics of Spatial P. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, Judy B. 1997. Demonstratives and reinforces in Romance and Germanic languages. Lingua 102: 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 2000. The ins and outs of contextual allomorphy. In University of Maryland Working Papers in Linguistics. Edited by Kleanthes K. Grohmann and Caro Struijke. Maryland: University of Maryland, pp. 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 2012. Universals in Comparative Morphology. Suppletion, Superlatives, and the Structure of Words. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugè, Laura. 1996. Demonstrative movement in Spanish: A comparative approach. University of Venice Working Papers in Linguistics 6: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brugè, Laura. 2002. The positions of demonstratives in the extended nominal projection. In Functional Structure in DP and IP: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque. Oxford: Oxford University Press, chp. 2. vol. 1, pp. 15–53. [Google Scholar]

- Caha, Pavel. 2009. The Nanosyntax of Case. Ph. D. thesis, University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Caha, Pavel. 2010. The parameters of case marking and spell out driven movement. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 10: 32–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caha, Pavel, and Marina Pantcheva. 2020. Locatives in Shona and Luganda. In Variation in P: Comparative Approaches to Adpositional Phrases. Edited by Jacopo Garzonio and Silvia Rossi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 19–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Jaehoon. 2014. Pronoun-Noun Constructions and the Syntax of DP. Ph.D. thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale. A Life in Language. Edited by Michael Kenstowicz. Cambridge and London: MIT Press, pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos, Christos, and Roberto Petrosino. 2018. Greek root-allomorphy without spans. In Proceedings of the 35th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Edited by William G. Bennett, Lindsay Hracs and Dennis R. Storoshenko. Sommerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 151–60. [Google Scholar]

- Corver, Norbert. 2017. Freezing effects. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Syntax, 2nd ed. Malden and Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, Giovanni Andrea. 1980. La “glossa” di Bova. Cento favole esopiche in greco calabro. Schema grammaticale, Lessico. Roccella Jonica: Associazione Culturale Jonica. [Google Scholar]

- Dékány, Éva Katalin. 2011. A Profile of the Hungarian DP. The Interaction of Lexicalization, Agreement and Linearization with the Functional Sequence. Ph.D. thesis, University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- den Dikken, Marcel. 2010. On the syntax of locative and directional prepositional phrases. In Mapping Spatial PPs, Volume 6 of the Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque and Luigi Rizzi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 74–126. [Google Scholar]

- Embick, David. 2010. Localism versus Globalism in Morphology and Phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embick, David. 2015. The Morpheme. A Theoretical Introduction. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embick, David. 2017. On the targets of phonological realization. In The Morphosyntax-Phonology Connection. Edited by Vera Gribanova and Stephanie S. Shih. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 255–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embick, David, and Rolf Noyer. 2001. Movement operations after syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 32: 555–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxepare, Ricardo. 2013. Basque primary adpositions from a clausal perspective. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 12: 41–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, Yehuda N. 2007. Do we wanna (or hafta) have empty categories? In Proceedings of LFG07. Edited by Miriam Butt and Tracy H. King. Stanford: CSLI Publications, pp. 184–97. [Google Scholar]

- Felice, Lydia. 2021. A novel argument for PF operations: STAMP morphs in Gã. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 6: 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, Giuliana. 1997. The categorial status of determiners. In The New Comparative Syntax. Edited by Liliane Haegeman. London and New York: Longman, pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, Giuliana. 2002. The functional structure of noun phrases. a bare phrase structure approach. In Functional Structure in DP in IP; The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 54–90. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw, Jane. 2005. Extended Projection. Revision of the 1991 Manuscript. Stanford: CSLI Publications, chp. 1. pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Guardiano, Cristina, and Dimitris Michelioudakis. 2019. Syntactic variation across greek dialects. In Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 319–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed Morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The View from Building 20. Edited by Ken Hale and Samuel J. Keyser. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 111–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hammarström, Harald, Robert Forkel, Martin Haspelmath, and Sebastian Bank. 2021. Glottolog 4.5. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harizanov, Boris, and Vera Gribanova. 2018. Whither head movement? Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 37: 461–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhn, Georg F. K. 2014. Contextually conditioned allomorphy and the Basque locative. Spelling out the Basque extended nominal projection. In ConSOLE XXI, Proceedings of the 21st Conference of the Student Organization of Linguistics in Europe, Potsdam, Germany, 8–10 January 2013. Edited by Martin Kohlberger, Kate Bellamy and Eleanor Dutton. Leiden: Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, pp. 146–70. [Google Scholar]

- Höhn, Georg F. K. 2016. Unagreement is an illusion: Apparent person mismatches and nominal structure. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34: 543–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, David, Peter Mackridge, Irene Philippaki-Warburton, and Vassilios Spyropoulos. 2012. Greek. A Comprehensive Grammar, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks, Geoffrey, and Melita Stavrou. 1987. Bounding theory and Greek syntax: Evidence for wh-movement in NP. Journal of Linguistics 23: 79–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, William H., Jr. 1977. The Basque locative suffix. In Anglo-American Contributions to Basque Studies: Essays in Honor of Jon Bilbao. Edited by William A. Douglass, Richard W. Etulain and William H. Jacobsen, Jr. Reno: Desert Research Institute, pp. 163–68. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, Marit. 2005. Nominal Phrases from a Scandinavian Perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, David, and Hadley Wickham. 2013. ggmap: Spatial visualization with ggplot2. The R Journal 5: 144–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanastasis, Anastasios. 1997. Γραμματική των ελληνικών ιδιομάτων της Κάτω Ίταλιας [Grammatiki ton ellinikon idiomaton tis Kato Italias]. Athens: Akadimia Athinon. [Google Scholar]

- Kremers, Joost. 2015. Morphology is in the eye of the beholder. Linguistische Berichte 243: 245–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 1970. Global rules. Language 46: 627–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marantz, Alec. 1997. No escape from syntax: Don’t try morphological analysis in the privacy of your own lexicon. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Penn Linguistics Colloquium, Volume 4 of U.Penn Working Papers in Linguistics. Edited by Alexis Dimitriadis, Laura Siegel, Clarissa Surek-Clark and Alexander Williams. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, pp. 201–25. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, Jason. 2015. How much context is enough? Two cases of span-conditioned stem allomorphy. Linguistic Inquiry 46: 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelioudakis, Dimitris. 2011. Dative arguments and abstract Case in Greek. Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Moskal, Beata. 2015a. Domains on the Border: Between Morphology and Phonology. Ph.D. thesis, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Moskal, Beata. 2015b. Limits on allomorphy: A case study in nominal suppletion. Linguistic Inquiry 46: 363–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskal, Beata, and Peter W. Smith. 2016. Towards a theory without adjacency: Hyper-contextual VI-rules. Morphology 26: 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, Heather. 2009. Aspects of the Morphology and Phonology of Phases. Ph.D. thesis, McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrove, Jason. 2018. Stretching, spanning, and linear adjacency in vocabulary insertion. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 36: 1263–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, Marjorie. 2016. How allomorphic is English article allomorphy? Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 1: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]