Teacher and SHL Student Beliefs about Oral Corrective Feedback: Unmasking Its Underlying Values and Beliefs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Varying Perspectives on Oral CF Beliefs

Beliefs on Whether Error Should Be Corrected

3. Overview of CF within the Field of SHL Education

3.1. The Eradication Approach

3.2. The Construct of Error Correction and Minoritized Learners

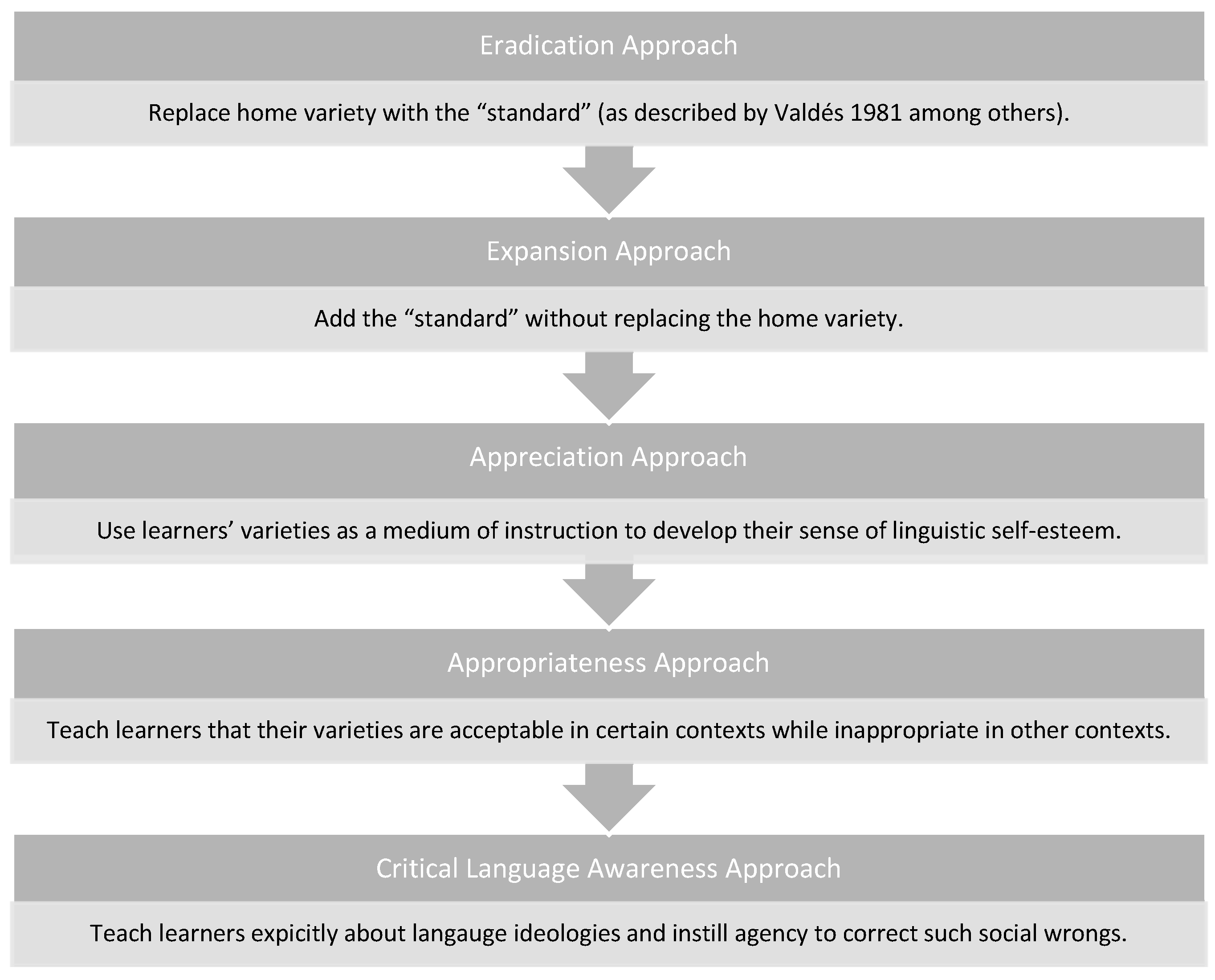

3.3. SHL Approaches to Language Variation

4. Study

4.1. Focal Participants

4.2. Research Instruments

- What language ideologies are prevalent in relation to participants’ conceptualizations of oral CF?

- How does the instructor define an SHL error?

- What is considered to be “good” CF for Spanish heritage language learners according to the instructor?

- What are the instructor’s goals for oral CF?

- How does this converge with language ideologies?

5. Findings

5.1. Theme 1: The Problem with SHL Learners’ Varieties

| Belinda: No olvide que yo clasificó a los alumnos [SHL] es por la cultura, yo hablo con un estudiante y yo de una vez sé, cómo es el lugar [de donde viene], porque la forma como la persona hable ahí está la educación que tiene. | Belinda: Don’t forget that I classify [SHL] students by their culture, I speak to a student and I know, what is the place [they come from] like, because the way a person speaks is the education that they have. |

| Utilizan [los estudiantes SHL] demasiadas palabras, yo sé que el pueblo las usa, pero eso no es lo normal…pero yo todos los días en las clases digo, “Yo puedo decir esa palabra, pero esa no es la correcta”, ese no es el nivel de español que queremos enseñarle. | They [SHL learners] use too many words, I know that the el pueblo uses, but that is not the norm…but every day in class I tell them, “I can say that word, but that is not the correct one”, that is not the level of Spanish that we want to teach them. |

| Belinda: Es que el problema que tenemos aquí en los Estados Unidos es por la frontera, porque ese idioma que tenemos aquí es idioma mexicano. | Belinda: It’s because the problem we have here in the United States is because of the border, because that language that we have here is a Mexican language. |

| Por ejemplo, dicen “Órale” o “Asina” y yo pues yo les dije, “No, no es asina, es así es- pero no asina”. Entonces, yo les describo la palabra, yo le descompongo la palabra y les explico por qué. | For example, they say “Órale” or “Asina”and I well told them, “No, its not xi, it is like that but not asina”. So I describe the word, I pull apart the word and I explain to them why. |

5.2. Theme 2: Spanglish Is Awkward but It Is Mine

| Myriam: | I don’t like Spanglish. Like I like it, but I just feel like, like, I don’t know, I just feel like either you’re gonna talk one language or the other one, because me traba…, I just feel like it’s awkward I don’t know. To me it’s a kind of weird. |

| Petra: | Because most my family is from here; all they talk is Spanglish. They don’t talk the correct form of Spanish. So, when I come into class and hear words that they’ve used differently, it kind of confuses me. |

| María: | With my family we talk more in Spanglish ‘cause like my brothers and sisters, they don’t know as much Spanish. Everyone’s in my family speaks slang… I feel like it’s kind of easier because like if you talk to someone like you don’t know kind of, but like you have a connection as soon as she started speaking. Spanglish. You have the best of both worlds from English and Spanish. |

| Reina: | Personally, I like Spanglish. I use it all the time…I think actually lots of Mexicans actually do like Spanglish…Mexicans that come over here, do speak a lot of Spanglish because they try to use the little English they know and like introduced that into their own vocabulary. |

5.3. Theme 3: “Good” CF for SHL’s Is Clear and Direct

| Belinda: Yo pienso que un profesor tiene que ser claro y también sobre todo clarificarle al estudiante que es lo que quiere…el estudiante termina por no saber que en realidad que-como son las ah-condiciones-para la evaluación-entonces el maestro tiene que ser directo, claro y persistente…con el estudiante sin humillarlo, ni menospreciarlo… | Belinda: I think that a teacher needs to be clear and also above all else clarify to the student what it is that you want…the student ends up not knowing what how- are the ah-conditions for the evaluation- and so the teacher has to be direct, clear and persistent…with students without humiliating them, nor underestimate them… |

| Belinda: …[si] el maestro está negativo… va a dañar eh a la-la parte emocional del estudiante y también el estudiante…puede entender esa corrección como una cosa negativa. | Belinda: …[if] the teacher is negative…they can damage um the-the emotional part of the student…the student can interpret that correction like something negative. |

| Yo los corrijo igual que a todos, siempre tratando de explicarles, cuáles son las ventajas de tener un lenguaje correcto -porque a veces… tienen [los Latinos] un vocabulario distinto y o un nivel más bajo- de no es normal. Entonces, les explico que la necesidad de mejorar el lenguaje… Entonces, yo les explico que estamos en la clase a un nivel más profesional y por consiguiente es necesario aprender el idioma correcto, no solamente hablado, sino escrito. | I correct everyone the same, I always try to explain to them, what are the advantages of having a correct language because sometimes…they [the Latinos] have a distinct vocabulary or a level that is lower that the norm. So…I explain to them the need to improve their language…So, I explain to them that we are in class which is a more professional level and, therefore, it is necessary to learn the correct language, not only spoken, but also written. |

5.4. Theme 4: CF Is Confusing

| Reina: | Usually she [Belinda] just like repeats the correct word but she but she doesn’t like say anything after. She says oración [correcting sentencia] then just keeps going. |

| Researcher: | O.K. and what do you think about that? |

| Reina: | Sometimes I don’t know what she’s talking about. Like I was just like, “O.K.”, just keep listen. |

| Researcher: | Does it work for you? |

| Reina: | Repetition works sometimes. |

| Researcher: | Repetition? |

| Reina: | Yeah, that’s just what my mom says, repetition, repetition, repetition. It helps to learn things and memorize them but honestly when I get corrected, I still don’t know what I did wrong. |

| Petra: | She would just, she would just say the word and if we didn’t say it right, she would just say the word again. Speaking wise, she’ll just pronounce the word. So, it’s more like repetition and she doesn’t really explain why but sometimes. |

| Researcher: | Um, do you think that’s helpful? |

| Petra: | Sometimes. Not all the time, like a few times. It just makes me more nervous because I feel like everyone stops to listen. |

| María: | She’ll just pronounce it the correct way and wait for me to say it properly and we’ll go on and on for a couple times. She doesn’t offer an explanation; she just corrects it. |

| Researcher: | Does it help you? |

| Myriam: | Not really because I’ll just forget it again like in ten minutes. |

5.5. Theme 5: Mejorar y No Dañar el Lenguaje

| Belinda: El español normal, dijéramos así, porque dentro del lenguaje existe el lenguaje que el pueblo lo habla, el lenguaje un poco a un nivel más alto, y el lenguaje que es lo perfecto del lenguaje. Perdón que diga, pero si usted se pone a ver en la televisión, en los noticieros, usted encuentra la diferencia del lenguaje. Usted coloca un noticiero o una televisión y usted va a notar que unas personas hablan con un lenguaje alto… Por qué, por ejemplo, si usted mira Univisión, ¿cuántas locutoras son colombianas de las que dan las noticias? Por el lenguaje. Ahí es donde yo digo, sí hay que pulir, hay que manejar y corregir para que la persona entienda que es necesario mejorar el lenguaje, no dañarlo. | Belinda: Normal Spanish, let’s call it that, because within language there exists the language that is spoken by people from el pueblo, the language that is slightly at a higher level, and language that is perfection. Sorry to say it, but if you watch television, in the news, you will find a difference in language. If you find a news cast or a television and you will notice that some people speak with a high language…Why, for example, if you watch Univision, how many broadcasters are Colombian of those who give the news? Because of the language. That’s why I say, yes lets polish, lets control and correct so that the person can understand that is it necessary to improve their language and not damage it. |

| Belinda: Nosotros [los colombianos] no somos inmigrantes así, siempre todos nos venimos [a los EE.UU] con título. Nosotros llamamos inmigrantes el que pasa la frontera sin permiso, esa es la idea que uno tiene de inmigrante, pero nosotros no somos inmigrantes en ese sentido, sino que la mayoría del 80% llega con sus papeles normales y entran normal. | Belinda: We [Colombians] are not immigrants like that, we always come [to the U.S.] with degrees. We call immigrants those that pass through the border without permission, that is the idea that one has about immigrants, but we are not immigrants in that sense, rather the 80% majority arrives with their papers normally and the enter normally. |

5.6. Theme 6: SHL Learner Resistance

| Reina: | Yeah, more like words I don’t hear anyone in my culture say. I’m learning, I’m trying to like get better at stuff so I could communicate better with people from my culture and like form for my family and I, if I use vosotros in front of them, they’ll roast me. Like, it’s not something I’m willing to do. |

| Petra: | I don’t think Belinda really likes Spanglish because most my family is, all they talk is Spanglish. They don’t talk the correct form of Spanish. So when I come into class and hear words that they’ve used differently, it kind of confuses me. |

| María: | She makes me feel stupid. I’m like “come on!” It [the word] still works the same for me you know. I still get places by using that word. I feel like my Spanish is the common everyday Spanish that you would hear not some boujee stuff where I’m going to be like O.K. I’m never going to use that again. |

| Myriam: | I feel like that at the same time. It’s awkward. It’s because people are not used to it. Like if I say bolígrafo people are going to be like “oh, what do you mean” instead of you say pen. |

6. Discussion

Expanding the Boundaries of CLA: Oral CF

- Teachers must reflect on the fact that they have the authority to initiate oral CF at their discretion as well as the authority to decide what counts as worthy knowledge within the classroom.

- Moving past narrow conceptualizations of CF must consider that the idea of correctness, about being corrected and about correcting others are all discursive practices that speakers engage with both inside and outside of the classroom. They may convey asymmetrical power relationships depending on the situational context and the relationship between the speakers.

- When teachers “correct” SHL learners’ varieties they are listening to a racialized speaking subject. Flores and Rosa’s (2015) scholarship brings attention to the ways that minoritized learners are often “heard” based on who they are and not on how they are able to model elite varieties that are conceived as being “professional” or “appropriate”. Because racialized learners are viewed as being inherently deficit speakers, pedagogues must learn to listen differently by gaining an awareness of the ideologies that underpin deficit perceptions of minoritized students.

- Educators must reflect openly and humbly on their own positionality as listeners, as language users, language learners, and the privileges they hold over their leaners.

- Pedagogues should cultivate a democratic classroom wherein critical metalinguistic awareness is welcomed. Learners should feel enabled to openly ask questions and even resist CF if they do not agree and engage in a socio-linguistically-based discussion that reaches beyond the appropriateness of language within the institutional context.

- CLA stimulates learners to gain a critical metalinguistic awareness of their own speech communities. This tenet can be extended to include SHL’s own self-awareness of the educational process to which they belong. Pedagogues should consider having open class conversations about the purpose and intent of CF and how it relates to the philosophy of the course; thereby, engaging learners in their own learning process.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acevedo, Rebeca. 2003. Navegando a través del registro formal. In Mi Lengua: Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States. Edited by Ana Roca and M. Cecilia Colombi. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 257–68. [Google Scholar]

- Agudo, Juan de Dios Martínez. 2014. Beliefs in learning to teach: EFL student teachers’ beliefs about corrective feedback. Utrecht Studies in Language and Communication 27: 209–362. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara M. 2015. Approaches to Language Variation: Goals and Objectives of the Spanish Heritage Language Syllabus. Heritage Language Journal 12: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., and Damián Wilson. 2022. Reimagining the goals of HL pedagogy through critical language awareness. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., and Sergio Loza. 2022. The central role of critical language awareness in Spanish heritage language education in the United States: An introduction. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., Angélica Amezcua, and Sergio Loza. 2019. Critical language awareness for the heritage context: Development and validation of a measurement questionnaire. Language Testing 36: 573–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., Angélica Amezcua, and Sergio Loza. 2021. Critical language awareness in the heritage language classroom: Design, implementation, and evaluation of a curricular intervention. International Multilingual Research Journal 15: 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Enríquez, Ysaura, and Eduardo Hernández-Chávez. 2003. La enseñanza del español en Nuevo México: ¿Revitalización o erradicación de la variedad chicana? In Mi Lengua: Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States. Edited by Ana Roca and M. Cecilia Colombi. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 96–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bessette, Ryan M., and Ana M. Carvalho. 2022. The structure of Spanish. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, Maria. 2000. Validating and promoting Spanish in the United States: Lessons from linguistic science. Bilingual Research Journal 24: 423–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, Maria, and Olga Kagan. 2011. The results of the National Heritage Language Survey: Implications for teaching, curriculum design, and professional development. Foreign Language Annals 44: 40–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, Maria, and Olga Kagan. 2018. Heritage language education: A proposal for the next 50 years. Foreign Language Annals 51: 152–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Ana M. 2012. Code-switching from theoretical to pedagogical considerations. In Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States: The State of the Field. Edited by Sara M. Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 139–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ducar, Cynthia Marie. 2006. (Re) Presentations of US Latinos: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Spanish Heritage Language Textbooks. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ducar, Cynthia Marie. 2008. Student voices: The missing link in the Spanish heritage language debate. Foreign Language Annals 41: 415–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod. 2009. Corrective feedback and teacher development. L2 Journal 1: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellis, Rod. 2017. Oral corrective feedback in L2 classrooms: What we know so far. In Corrective Feedback in Second Language Teaching and Learning. Edited by Hossein Nassaji and Eva Kartchava. New York: Routledge, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2010. Critical Discourse Analysis. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Nelson, and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review 85: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitiérrez, John R. 1997. Teaching Spanish as a heritage language: A case for language awareness. ADFL Bulletin 29: 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín Mendoza, Claudia. 2018. Critical language awareness (CLA) for Spanish heritage language programs: Implementing a complete curriculum. International Multilingual Research Journal 12: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, Barbara. 2018. Discourse Analysis. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo-Brown, Kimi. 2003. Heritage language instruction for post-secondary students from immigrant backgrounds. Heritage Language Journal 1: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroskrity, Paul V. 2010. Language ideologies: Evolving perspectives. In Society and Language Use. Edited by Jürgen Jaspers, Jef Verschueren and Jan-Ola Östman. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 192–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, Steinar, and Svend Brinkmann. 2015. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lacorte, Manel, and José L. Magro. 2022. Foundations for critical and antiracist heritage language teaching. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2005. Engaging critical pedagogy: Spanish for native speakers. Foreign Language Annals 38: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2010. Introduction. The sociopolitics of heritage language education. In Spanish of the U.S. Southwest: A Language in Transition. Edited by Susana V. Rivera-Mills and Daniel J. Villa. Norwalk: Iberoamericana Vervuert Publishing Co., pp. 309–17. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2012. Investigating language ideologies in Spanish as a heritage language. In Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States: The State of the Field. Edited by Sara M. Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Shaofeng. 2017. Student and teacher beliefs and attitudes about oral corrective feedback. In Corrective Feedback in Second Language Teaching and Learning: Research, Theory, Applications, Implications. Edited by Hossein Nassaji and Eva Kartchava. New York: Routledge, pp. 143–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lowther Pereira, Kelly Anne. 2010. Identity and Language Ideology in the Intermediate Spanish Heritage Language Classroom. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Loewen, Shawn, Shaofeng Li, Fei Fei, Amy Thompson, Kimi Nakatsukasa, Seongmee Ahn, and Xiaoqing Chen. 2009. Second language learners’ beliefs about grammar instruction and error correction. The Modern Language Journal 93: 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza, Sergio. 2019. Exploring Language Ideologies in Action: An Analysis of Spanish Heritage Language Oral Corrective Feedback in the Mixed Classroom Setting. Ph.D. dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Loza, Sergio. 2022. Oral corrective feedback in the Spanish heritage language context: A critical perspective. In Heritage Language Teaching: Critical Language Awareness for Research and Pedagogy. Edited by Sergio Loza and Sara M. Beaudrie. New York: Routledge, pp. 119–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lyster, Roy, Kazuya Saito, and Masatoshi Sato. 2013. Oral corrective feedback in second language classrooms. Language Teaching 46: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, Catherine, and Gretchen B. Rossman. 2016. Designing Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Glenn. 2003. Classroom based dialect awareness in heritage language instruction: A critical applied linguistic approach. Heritage Language Journal 1: 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, Joseph A. 2013. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Porras, Jorge. 1997. Uso local y uso estándar: Un enfoque bidialectal a la enseñanza del español para nativo. In La Enseñanza Del Español a Hispanohablantes: Praxis y Teoría. Edited by María Cecilia Colombi and Francisco Alarcón. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 190–98. [Google Scholar]

- Potowski, Kim. 2005. Fundamentos de la Enseñanza del Español a Hispanohablantes en los EE.UU. Madrid: Arcos Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Tracy. 2020. Critical language awareness and L2 learners of Spanish: An action-research study. Foreign Language Annals 53: 897–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Tracy. 2021. Critical Approaches to Spanish Language Teacher Education: Challenging Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Fostering Critical Language Awareness. Hispania 104: 447–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, Muhammad, and Lawrence Jun Zhang. 2015. Exploring non-native English-speaking teachers’ cognitions about corrective feedback in teaching English oral communication. System 55: 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razfar, Aria. 2010. Repair with confianza: Rethinking the context of corrective feedback for English learners (ELs). English Teaching: Practice and Critique 9: 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Reisigl, Martin, and Ruth Wodak. 2016. The discourse-historical approach. In Methods of Critical Discourse Studies. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 23–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pino, Cecilia. 1997. La reconceptualización del programa de español para hispano hablantes: Estrategias que reflejan la realidad sociolingüística en la clase. In La enseñanza del Español a Hispanohablantes: Praxis y teoría. Edited by María Cecilia Colombi and Francisco Alarcón. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pino, Cecilia, and Daniel Villa. 1994. A student-centered Spanish-for-native-speakers program: Theory, curriculum design, and outcome assessment. In Faces in a Crowd: The Individual Leaner in Multisection Courses. Edited by Carol A. Klee. Boston: Heinle and Heinle Publishers, pp. 355–77. [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego, Fabián, and Cecilia Pino. 2000. Frequently asked questions about SNS programs. In Spanish for Native Speakers. Edited by AATSP. Fort Worth: Harcourt College, vol. 1, pp. 29–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Rosaura. 1981. Spanish for native speakers at the university: Suggestions. In Teaching Spanish to the Hispanic Bilingual: Issues, Aims and Methods. Edited by Guadalupe Valdés, Anthony Lozano and Rodolfo Garcia Moya. New York: Teachers College Press, pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, Renate A. 1996. Focus in the foreign language classroom: Students’ and teachers’ views on error correction and the role of grammar. Foreign Language Annals 29: 343–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, Younghee. 2006. Exploring the relationship between characteristics of recasts and learner uptake. Language Teaching Research 10: 361–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenk, Elaine M. 2014. Teaching sociolinguistic variation in the intermediate language classroom: Voseo in Latin America. Hispania 97: 368–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 1981. Pedagogical implications of teaching Spanish to the Spanish-speaking in the United States. In Teaching Spanish to the Hispanic Bilingual: Issues, Aims and Methods. Edited by Guadalupe Valdés, Anthony Lozano and Rodolfo Garcia Moya. New York: Teachers College Press, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés-Fallis, Guadalupe. 1978. A comprehensive approach to the teaching of Spanish to bilingual Spanish-speaking students. Modern Language Journal 35: 102–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe, Sonia V. González, Dania López García, and Patricio Márquez. 2003. Language ideology: The case of Spanish in department of foreign language. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 34: 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, Teun A. 2016. Critical discourse studies: A sociocognitive approach. In Methods of Critical Discourse Studies. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishers, pp. 62–85. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, Daniel J. 1996. Choosing a “standard” variety of Spanish for the instruction of native Spanish speakers in the US. Foreign Language Annals 29: 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | First Language | Years of Formal Education in Spanish | Place of Birth | Parents’ Immigration to U.S. | Grandparents’ Immigration to U.S. | Generation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| María | Spanish | 14 years | U.S./California | Yes | No | 2nd |

| Reina | Spanish | 2 years in high school | U.S./AZ | Yes | No | 2nd |

| Myriam | Spanish | 2 years in high school | U.S./AZ | Yes | No | 2nd |

| Petra | English | 3 years in high school | U.S./AZ | No | Yes | 3rd |

| Instructor | Education | Language Teaching Experience | Country of Origin | Training on SHL Teaching |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belinda | B.A. Spanish and Communication (Latin America) M.A. Education with a focus in Early Childhood Education (U.S.) M.S. Professional Guidance and School Counseling (Latin America) | 50 years of teaching experience | Colombia | No |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loza, S. Teacher and SHL Student Beliefs about Oral Corrective Feedback: Unmasking Its Underlying Values and Beliefs. Languages 2022, 7, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030194

Loza S. Teacher and SHL Student Beliefs about Oral Corrective Feedback: Unmasking Its Underlying Values and Beliefs. Languages. 2022; 7(3):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030194

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoza, Sergio. 2022. "Teacher and SHL Student Beliefs about Oral Corrective Feedback: Unmasking Its Underlying Values and Beliefs" Languages 7, no. 3: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030194

APA StyleLoza, S. (2022). Teacher and SHL Student Beliefs about Oral Corrective Feedback: Unmasking Its Underlying Values and Beliefs. Languages, 7(3), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030194