The Role Classifiers Play in Selecting the Referent of a Word

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Acquisition of Mandarin Classifiers

1.2. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Child Participants

2.2. Visual and Auditory Stimuli

2.3. Apparatus and Procedure

2.4. Coding and Data Analysis

2.5. Stimulus Verification, Typicality Rating, Familiarity, and Visual Similarity Rating in Adults

3. Results

3.1. Adults’ Data: Experimental Checks

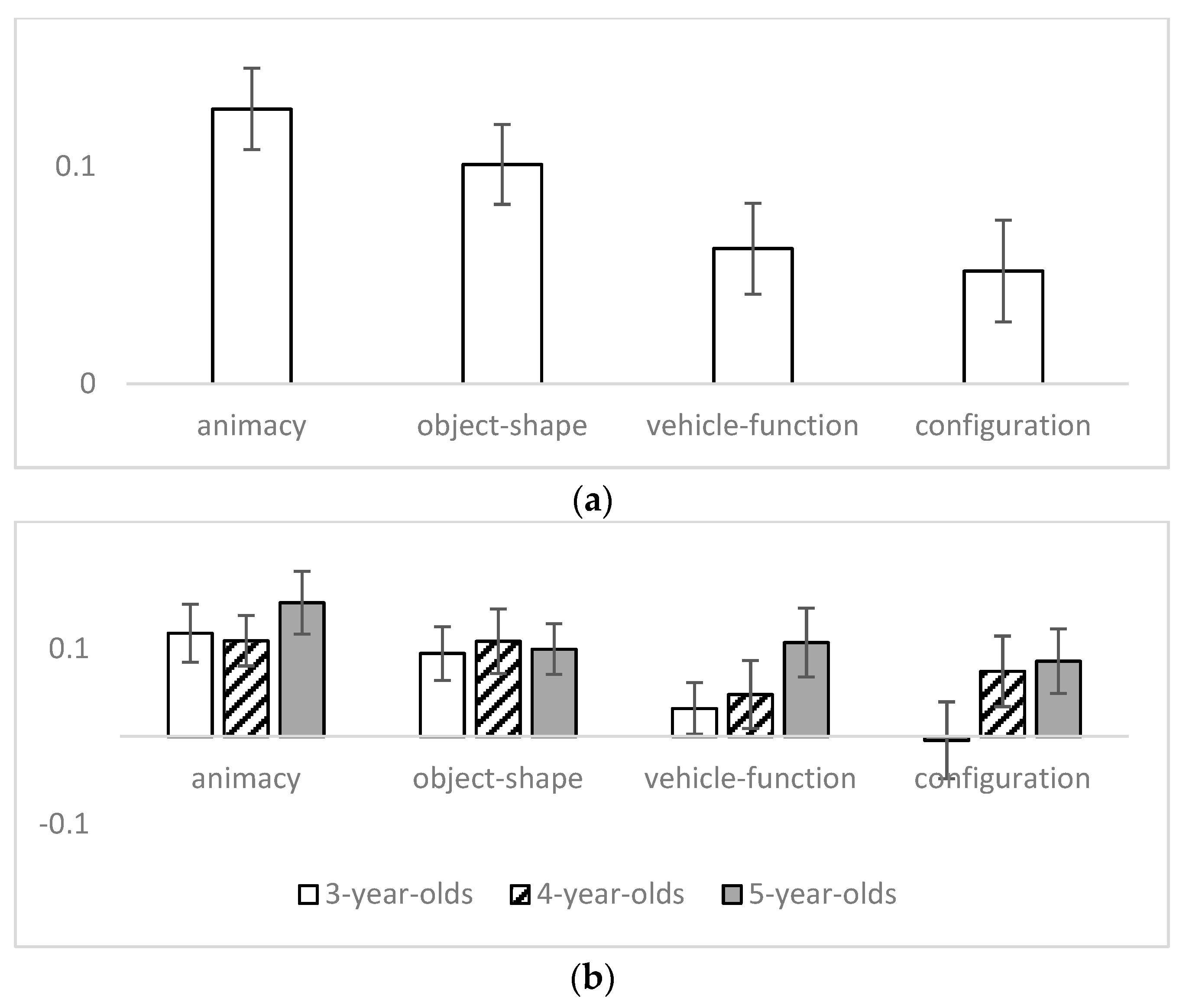

3.2. Children’s Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The strike above a vowel denotes the lexical tone of the Mandarin Chinese character. There are four basic tones in Mandarin. Tones are distinctive features in Mandarin. For example, mā with a high, level tone means mother; má with a rising tone means numb; mǎ with a dipping tone means horse; and mà with a falling tone means to curse. |

| 2 | We also examined a subset of the early-acquired nouns that were analyzed by Ma et al. (2019). Only words that occurred with classifiers at least once in the CHILDES Beijing Corpus were analyzed. The final sample contained 29 nouns, 28 of which occurred with the generic classifier (gè), and one occurred only with specific classifiers. We first asked adult participants to list the most appropriate classifiers that could modify these nouns and then to judge the appropriateness of the use of gè in child-directed speech. To rule out possible influences between tasks, two separate groups of Mandarin-speaking undergraduate students (majors in disciplines other than linguistics) in China participated. For the fill-in-the-blank task, 24 participants were asked to provide the most appropriate classifier for each of the 29 nouns, based on the following instruction written in Chinese: “Please write down the most appropriate classifier to fill in the blank. For example, in yí [one] ___ rén [people], you may write down gè in the blank if you believe that it is the most appropriate classifier to fill in the blank based on your knowledge of Chinese.” For each noun, we calculated the rate of gè use by dividing the token frequency of gè over the total token frequency of classifiers (combining the generic and specific classifiers). The mean rate of gè use was 0.76 (SD = 0.33) across the 29 nouns. A one-sample t-test comparing the mean rate of gè against chance (0.5; generic vs. specific) found that it was significantly above chance (t(28) = 4.16, p < 0.001), suggesting that caregivers were more likely to use gè than specific classifiers. Is gè the most appropriate classifier to modify these nouns? The result showed that for only 7 (24% of 29) nouns, gè was listed (among specific classifiers) as the most appropriate classifier. A sign test showed that across the 29 nouns, gè was less likely to be the most appropriate classifier than specific classifiers (p < 0.01). For each noun, we divided the responses of gè being listed as the most appropriate classifier over the total number of responses (n = 24). A one-sample t-test comparing the mean rate of gè being listed as the most appropriate classifier against chance (0.5; generic vs. specific) showed that it was significantly below chance (t(28) = 5.08, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.07). Thus, gè is less likely to be the most appropriate classifier than specific classifiers to modify the 29 nouns selected. Then, the use of gè was further analyzed. Another 24 undergraduate students rated the appropriateness of the phrases containing gè and each of the 28 nouns that appeared with gè at least once in CHILDES Beijing Corpus. The task consisted of 28 items, each presenting a phrase in the form of “yí [one] gè [classifier] noun.” The instruction was presented in Chinese, “Please judge whether the following phrases are good examples of Chinese based on a scale from 1 to 9, where 1 means very bad, 3 means bad, 5 means not bad or not good, 7 means good, 9 means very good, and the numbers in between mean moderately good or bad. Please focus on the use of classifiers during the task.” This analysis focused on the 28 nouns that appeared with gè at least once in the child-directed speech corpus. The use of gè received a mean appropriateness rating of 3.98 (SD = 2.59). Since the fill-in-the-blank task showed that 7 of the nouns could most appropriately occur with gè, and 21 of them could only occur with specific classifiers, the two types of words were analyzed separately. We found that the 7 nouns received a rating of 7.98 (SD = 0.51), verifying the results of the fill-in-the-blank task. The 21 nouns received a rating of 2.65 (SD = 1.22), suggesting that gè was used inappropriately with these nouns based on Mandarin grammar. Taken together, these findings show that Mandarin-speaking caregivers tend to overuse the generic classifier—gè, even when it is inappropriate. |

References

- Allan, Keith. 1977. Classifiers. Language 53: 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Yuen-Ren. 1968. A Grammar of Spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Lisa L. S., and Rint Sybesma. 1998. Yi-wan tang, yi-ge tang: Classifiers and massifiers. Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies 28: 385–412. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Lisa L. S., and Rint Sybesma. 1999. Bare and not-so-bare nouns and the structure of NP. Linguistic Inquiry 30: 509–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chien, Yu-Chin, Barbara Lust, and Chi-Pang Chiang. 2003. Chinese children’s comprehension of count-classifiers and mass-classifiers. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 12: 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Robin P., and Richard N. Aslin. 1990. Preference for infant-directed speech in the first month after birth. Child Development 61: 1584–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cycowicz, Yael M., David Friedman, Mairay Rothstein, and Joan Gay Snodgrass. 1997. Picture naming by young children: Norms for name agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 65: 171–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Da, Jun. 2004. A corpus-based study of character and bigram frequencies in Chinese e-texts and its implications for Chinese language instruction. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on New Technologies in Teaching and Learning Chinese. Edited by Pu Zhang, Tianwei Xie and Juan Xu. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, pp. 501–11. [Google Scholar]

- Diesendruck, Gil, Lori Markson, and Paul Bloom. 2003. Children’s reliance on creator’s intent in extending names for artifacts. Psychological Science 14: 164–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbaugh, Mary S. 1986. Taking stock: The development of Chinese noun classifiers historically and in young children. In Noun Classes and Categorization. Edited by Colette G. Craig. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 399–436. [Google Scholar]

- Erbaugh, Mary S. 2006. Chinese classifiers: Their use and acquisition. In Handbook of East Asian Psycholinguistics: Chinese. Edited by Ping Li, Lihai Tan, Elizabeth Bates and Ovid J. L. Tzeng. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Fuxi. 1985. An experiment on the use of classifiers by 4- to 6-year-olds. Acta Psychologica Sinica 17: 384–92. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, Franz, Edgar Erdfelder, Albert-Georg Lang, and Axel Buchner. 2007. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 39: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernald, Anne. 1985. Four-month-olds prefer to listen to motherese. Infant Behavior and Development 8: 181–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleitman, Lila R., and John C. Trueswell. 2020. Easy words: Reference resolution in a malevolent referent world. Topics in Cognitive Science 12: 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golinkoff, Roberta Michnick, He Len Chung, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Jing Liu, Bennett I. Bertenthal, Rebecca Brand, Mandy J. Maguire, and Elizabeth Hennon. 2002. Young children can extend motion verbs to point-light displays. Developmental Psychology 4: 604–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golinkoff, Roberta Michnick, Roberta Jacquet, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, and Ratna Nandakumar. 1996. Lexical principles may underlie the learning of verbs. Child Development 67: 3101–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golinkoff, Roberta M., Weiyi Ma, Lulu Song, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. 2013. Twenty-five years using the intermodal preferential looking paradigm to study language acquisition: What have we learned? Perspectives on Psychological Science 8: 316–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Gomez, Nayeli, Silvana Poltrock, and Thierry Nazzi. 2013. A “bat” is easier to learn than a “tab”: Effects of relative phonotactic frequency on infant word learning. PLoS ONE 8: e59601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Susan A., and Diane Poulin-Dubois. 1999. Infants’ reliance on shape to generalize novel labels to animate and inanimate objects. Journal of Child Language 26: 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Ying. 2019. How Do Mandarin-Speaking Children Learn Shape Classifiers? Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Heron-Delaney, Michelle, Sylvia Wirth, and Olivier Pascalis. 2011. Infants’ knowledge of their own species. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 366: 1753–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hollich, George. 2005. Supercoder: A Program for Coding Preferential Looking. Version 1.5, Computer Software. West Lafayette: Purdue University. [Google Scholar]

- Hollich, George, Roberta M. Golinkoff, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. 2007. Young children associate novel words with complex objects rather than salient parts. Developmental Psychology 43: 1051–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horst, Jessica S. 2009. Novel Object and Unusual Name (NOUN) Database. Available online: http://www.sussex.ac.uk/wordlab/noun (accessed on 9 January 2017).

- Hu, Qian. 1993. The Acquisition of Chinese Classifiers by Young Mandarin-Speaking Children. Ph.D. dissertation, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Killingley, Siew-Yue. 1983. Cantonese Classifiers: Syntax and Semantics. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Grevatt and Grevatt. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, Barbara, Linda B. Smith, and Susan S. Jones. 1988. The importance of shape in early lexical learning. Cognitive Development 3: 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Peggy, Becky Huang, and Yaling Hsiao. 2010. Learning that classifiers count: Mandarin-speaking children’s acquisition of sortal and mensural classifiers. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 19: 207–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Peggy, David Barner, and Becky H. Huang. 2008. Classifiers as count syntax: Individuation and measurement in the acquisition of Mandarin Chinese. Language Learning and Development 4: 249–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Loke, K. K. 1991. A Semantic Analysis of Young Children’s Use of Mandarin Shape Classifiers. In Child Language Development in Singapore and Malaysia. Edited by Anna Kwan-Terry. Singapore: Singapore University Press, pp. 98–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Weiyi, and Peng Zhou. 2019. Three-year-old tone language learners are tolerant of tone mispronunciations spoken with familiar and novel tones. Cogent Psychology 6: 1690816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Weiyi, Anna Fiveash, Elizabeth Margulis, Douglas Behrend, and Willian Forde Thompson. 2020a. Song and infant-directed speech facilitate word learning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 73: 1036–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Weiyi, Peng Zhou, and Roberta M. Golinkoff. 2020b. Young Mandarin learners use function words to distinguish between nouns and verbs. Developmental Science 23: e12927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Weiyi, Peng Zhou, and William Forde F Thompson. 2022a. Children’s decoding of emotional prosody in four languages. Emotion 22: 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Weiyi, Peng Zhou, Leher Singh, and Liqun Gao. 2017. Spoken word recognition in young tone language learners: Age-dependent effects of segmental and suprasegmental variation. Cognition 159: 139–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Weiyi, Peng Zhou, Roberta M. Golinkoff, Joanne Lee, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. 2019. Syntactic cues to the noun and verb distinction in Mandarin child-directed speech. First Language 39: 433–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Weiyi, Roberta M. Golinkoff, Derek Houston, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. 2011. Word learning in infant-and adult-directed speech. Language Learning and Development 7: 209–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, Weiyi, Roberta M. Golinkoff, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Colleen McDonough, and Twila Tardif. 2009. Imageability predicts the age of acquisition of verbs in Chinese. Journal of Child Language 36: 405–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, Weiyi, Roberta M. Golinkoff, Lulu Song, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. 2021. Using verb extension to gauge children’s verb meaning construals: The case of Chinese. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 572198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Weiyi, Rufan Luo, Robert M. Golinkoff, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. 2022b. The influence of exemplar variability on young children’s construal of verb meaning. Language Learning and Development. (advance online publication). [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Mandy J., Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Roberta M. Golinkoff, and Amanda C. Brandone. 2008. Focusing on the relation: Fewer exemplars facilitate children’s initial verb learning and extension. Developmental Science 11: 628–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, Nivedita, and Kim Plunkett. 2007. Phonological specificity of vowels and consonants in early lexical representations. Journal of Memory and Language 57: 252–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meints, Kerstin, Kim Plunkett, and Paul L. Harris. 1999. When does and ostrich become a bird? The role of typicality in early word comprehension. Developmental Psychology 35: 1072–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meints, Kerstin, Kim Plunkett, and Paul L. Harris. 2008. Eating apples and houseplants: Typicality constraints on thematic roles in early verb learning. Language and Cognitive Processes 23: 434–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meints, Kerstin, Kim Plunkett, Paul L. Harris, and Debbie Dimmock. 2002. What is ‘on’ and ‘under’ for 15-, 18-and 24-month-olds? Typicality effects in early comprehension of spatial prepositions. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 20: 113–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Katherine. 1988. Constraints on word learning? Cognitive Development 3: 221–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Lynn K., and Larissa K. Samuelson. 2011. The shape of the vocabulary predicts the shape of the bias. Frontiers in Psychology 2: 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quam, Carolyn, and Dniel Swingley. 2010. Phonological knowledge guides two-year-olds’ and adults’ interpretation of salient pitch contours in word learning. Journal of Memory and Language 62: 135–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quinn, Paul C., and Peter D. Eimas. 1998. Evidence for a global categorical representation of humans by young infants. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 69: 151–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, Larissa K., and Linda B. Smith. 2000. Children’s attention to rigid and deformable shape in naming and non-naming tasks. Child Development 71: 1555–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Leher, Hwee Hwee Goh, and Thilanga D. Wewalaarachchi. 2015. Spoken word recognition in early childhood: Comparative effects of vowel, consonant and lexical tone variation. Cognition 142: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, Leher, Tam Jun Hui, Calista Chan, and Roberta M. Golinkoff. 2014. Influences of vowel and tone variation on emergent word knowledge: A cross-linguistic investigation. Developmental Science 17: 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Linda B. 2000. Learning how to learn words: An associative crane. In Breaking the Word Learning Barrier: What Does It Take? Edited by Roberta M. Golinkoff and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. New York: Oxford Press, pp. 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, Mahesh, and Jesse Snedeker. 2014. Polysemy and the taxonomic constraint: Children’s representation of words that label multiple kinds. Language Learning and Development 10: 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swingley, Daniel, and Richard N. Aslin. 2000. Spoken word recognition and lexical representation in very young children. Cognition 76: 147–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swingley, Daniel, and Richard N. Aslin. 2002. Lexical neighborhoods and the word-form representations of 14-month-olds. Psychological Science 13: 480–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tai, J. H. 1994. Chinese classifier systems and human categorization. In In Honor of William S.-Y. Wang: Interdisciplinary Studies on Language and Language Change. Nottingham: Pyramid Press, pp. 479–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tardif, Twila, Paul Fletcher, Zhixiang Zhang, Weilan Liang, and Q. H. Zuo. 2008. The Chinese Communicative Development Inventory (Putonghua and Cantonese Versions): Manual, Forms, and Norms. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, Shek Kam, Hui Li, and Shing On Leung. 2007. The acquisition of Cantonese classifiers by preschool children in Hong Kong. Journal of Child Language 34: 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werker, Janet F., Judith E. Pegg, and Peter McLeod. 1994. A cross-language comparison of infant preference for infant-directed speech: English and Cantonese. Infant Behavior and Development 17: 321–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Katherine S., and Richard N. Aslin. 2011. Adaptation to novel accents by toddlers. Developmental Science 14: 372–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ying, Houchang, Guopeng Chen, Zhengguo Song, Weiming Shao, and Ying Guo. 1983. 4–7 Sui Ertong Zhangwo Liangci De Tedian [Characteristics of 4-to-7-year-olds in Mastering Classifiers]. Information on Psychological Sciences 26: 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Hong. 2007. Numeral classifiers in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 16: 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Peng, and Weiyi Ma. 2018. Children’s use of morphological cues in real-time event representation. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 47: 241–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Animacy | pair 1 | wèi: polite classifier for people | zhī: animals |

| pair 2 | míng: classifier for people | tóu: domesticated animals | |

| Configuration | pair 1 | qún: group, herd | pái: a straight line, queue |

| pair 2 | shuāng: pair | zhī: a single one | |

| Vehicle function | pair 1 | liàng: wheeled land vehicles (e.g., car) | sōu: water vehicles (e.g., ship) |

| pair 2 | jià: winged flying vehicles (e.g., plane) | liè: long, arrayed vehicles (e.g., train) | |

| Object shape | pair 1 | gēn: thin, slender, pole, stick objects | zhāng: flat objects |

| pair 2 | lì: small, grain-like objects | tiáo: long, narrow objects |

| Trial | Carrier Phrase | Character by Character English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kuài Kàn! Zhè-er yǒu yì pái | Quickly look! There is one classifier … |

| 2 | Kàn! Nà shì yì gēn … | Look! That is one classifier … |

| 3 | Kàn kàn! Nǎ gè shì yí lì … | Look, look! Which one is one classifier … |

| 4 | Qiáo! Zhè-lǐ yǒu yì sōu … | Look! Here exists one classifier … |

| 5 | Nǐ qiáo! Zhè shì yì zhī … | You look! Here is one classifier … |

| 6 | Kuài qiáo! Nà-er shì yì shuāng … | Quickly look! There is one classifier … |

| 7 | Kuài qiáo! Nà-er shì yì míng … | Quickly look! There is one classifier … |

| 8 | Kuài Kàn! Zhè-er yǒu yì liàng … | Quickly look! Here exists one classifier … |

| 9 | Kuài qiáo! Nà-er shì yì tiáo … | Quickly look! There is one classifier … |

| 10 | Kàn kàn! Nǎ gè shì yì zhī … | Look, look! Which one is one classifier … |

| 11 | Qiáo! Zhè-lǐ yǒu yì qún … | Look! Here exists one classifier … |

| 12 | Nǐ qiáo! Zhè shì yì zhāng … | You look! This is one classifier … |

| 13 | Nǐ qiáo! Zhè shì yí liè … | You look! This is one classifier … |

| 14 | Kàn kàn! Nǎ gè shì yì tóu … | Look, look! Which one is one classifier … |

| 15 | Kàn! Nà shì yí wèi … | Look! That is one classifier … |

| 16 | Kàn! Nà shì yí jià … | Look! That is one classifier … |

| Left Side | Right Side | Speech Stimuli | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animacy |  |  | Kàn [look]! Nà [that] shì [is] yí [one] wèi [classifier] shénme [something] |

| Configuration |  |  | Kuài [quickly] Kàn [Look]! Zhè er [here] yǒu [exist] yì [one] pái [classifier] shénme [something] |

| Vehicle function |  |  | Kàn [Look]! Nà [that] shì yí [one] jià [classifier] shénme [something] |

| Object shape |  |  | Nǐ [you] qiáo [look]! Zhè [this] shì [is] yì [one] zhāng [classifier] shénme [something] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, W.; Zhou, P.; Golinkoff, R.M. The Role Classifiers Play in Selecting the Referent of a Word. Languages 2023, 8, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010084

Ma W, Zhou P, Golinkoff RM. The Role Classifiers Play in Selecting the Referent of a Word. Languages. 2023; 8(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Weiyi, Peng Zhou, and Roberta Michnick Golinkoff. 2023. "The Role Classifiers Play in Selecting the Referent of a Word" Languages 8, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010084

APA StyleMa, W., Zhou, P., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2023). The Role Classifiers Play in Selecting the Referent of a Word. Languages, 8(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010084