The Syntax–Pragmatics Interface in Heritage Languages: The Use of anche (“Also”) in German Heritage Speakers of Italian

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Functions of Auch and Anche

2.1. Additive Particle

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- 1a. Auch [PETER]DA/Focus hat bei Lucie angerufen.

- 6a. In den Urlaub ist [Johannes]DA/Topic [AUCH]Focus gefahren.

- 7a. [Johannes]DA/Topic ist [AUCH]Focus in den Urlaub gefahren.

|

|

2.2. Sentence Connective

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.3. Modal Particle

- they are always syntactically integrated and never appear in sentence-initial position (not even when this position is syntactically integrated);

- their occurrence is restricted to certain sentence/illocutive types;

- they express modality at the sentence level.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.4. Summary: Partial Overlap

3. Previous Studies on the Acquisition of Anche

| 24. | sentence1 anche sentence2 (anche as a sentence connective) |

|

|

- If (and only if) HerIt resembles L2 Italian in the use of anche, then its use should be comparable to that of HomIt:

- when the DA is the preverbal subject (cf. Andorno and Turco 2015; Caloi 2017);

- when anche is adjacent to the DA (Andorno 2000);

- If IHSs mirror L2 language learners in the production of anche, then their production differs from HomIt in the following respects:

- Anche should occur in a fixed position within the clause, unlike in HomIt (Caloi 2017);

- It should not show the same intonation as in HomIt, but the intonational pattern should have CLI from the dominant language, German (as shown for L2 speakers by Andorno and Turco 2015).

4. Materials and Methods

- 12 interviews conducted in German and 12 interviews conducted in Italian with IHSs who grew up in Germany and have German as their dominant language;

- 8 interviews conducted in Italian and 8 interviews conducted in German with German HSs who grew up in Italy and have Italian as their dominant language;

- 15 interviews conducted in Italian with German L2 speakers of Italian;

- 19 interviews conducted in German with Italian L2 speakers of German.

5. Results

|

|

5.1. Anche as an Additive Particle

5.1.1. Types of Deviant Realizations

- anche is right adjacent to the DA, which is usually preverbal (marginally possible in HomIt);

- anche occurs in a discontinuous construction, i.e., it immediately follows the inflected verb, while the DA is in the first position or in an internal position lower than anche (“DA—V anche” or “anche—XP—DA”);

- the DA is phonetically null; anche usually follows the inflected verb, as in type 2.

|

| 31. | INT-GIU: | e | # ti | è piaciuta questa scuola? | |||

| ‘and did you like this school?’ | |||||||

| HS4: | così cosà | ||||||

| ‘so-and-so’ | |||||||

| HS4: | non ci andrei di nuovo | ||||||

| ‘I wouldn’t go there again’ | |||||||

| INT-GIU: | perché che cosa non ti è piaciuto? | ||||||

| ‘Why, what didn’t you like?’ | |||||||

| HS4: | sì # li # l’insegnamento | ||||||

| ‘well the teaching’ | |||||||

| HS4: | e | [l’insegnante]DA anche non mi | son piaciuti molto | ||||

| and the teachers | also | not me | are pleased much | ||||

| ‘and I didn’t like the teachers much either’27 | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.1.2. Total Number of Occurrences

5.1.3. Syntactic Properties of the Production of Anche as an Additive Particle

|

|

5.1.4. Prosodic Properties of the Deviant Realizations

5.1.5. Interim Summary

5.2. Anche as a Sentence Connective

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 50. | c’è tanta roba anche tutti gli antipasti # &eh. anche come sa (= il sapore) la carne 30 |

| ‘There’s a lot of stuff, also all the starters, and [I also like] how the meat tastes’ |

5.3. Anche as a Modal Particle

|

|

|

5.4. Other Cases

5.4.1. Ambiguous Occurrences

|

|

|

5.4.2. “Assertive” Anche

|

|

|

|

|

6. Discussion

6.1. The Use of Anche as a Sentence Connective

6.2. The Use of Anche as a Modal Particle

6.3. The Use of Anche as an Additive Particle

|

|

- Overall properties of topicalization in HerIt;

- Properties of the use of anche;

- Evidence coming from other moved elements;

- Theory-internal reasons.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | We follow the definition of heritage language given by Rothman (2009, p. 156): a heritage language is a language acquired through naturalistic input because it is spoken “at home or otherwise readily available to young children, and crucially this language is not a dominant language of the larger (national) society.” |

| 3 | “Attrition” is a process affecting bilingual speakers, whereby they lose some grammatical structures after having acquired them to a full extent. The typical case concerns adolescents or adults that move to another country, where they use their L1 less than the language of the new country (see, e.g., Seliger 1996). |

| 4 | The study of cross-linguistic variation has been an important topic in generative grammar since the Government and Binding period (Chomsky 1981). Subsequently, a new line of research dedicated to the formal study of microvariation (i.e., variation in closely related varieties) arose, see, e.g., Kayne (1996, 2005). |

| 5 | Of course, from such a point of view, it makes no sense to refer to concepts such as “target-like/non-target-like”, or similar. We, therefore, consider heritage Italian to “match/not match” the grammar of homeland Italian, in order to refer to rules that correspond (or do not) in the two varieties. In the same vein, we use “deviant” in the objective sense of “differing from the HomIt rules”, but this does not imply a (despective) judgement on the value of HerIt. |

| 6 | We use the term “Homeland Italian”, and not “standard Italian” or “neo-standard Italian” for two reasons: first, we follow the tradition of psycholinguistic and formal studies on heritage languages, which contrast a heritage language with the (varieties of) language spoken in the homeland, by speakers that have not had strong contact with another language. Second, we avoid “standard” Italian because this term refers rather to a written, normed register than to the oral register that is typically the input for children acquiring their L1. |

| 7 | A “mixed” pattern is of course possible as well: anche has already changed in the production of the attrited parents, but then HSs went further, adding new, innovative properties to the parents’ pattern. In any case, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies on the production of anche by first-generation immigrants that moved from Italy to Germany. Therefore, it is impossible to reconstruct the baseline, i.e., the main source of input to which the heritage speakers were exposed. |

| 8 | As an anonymous reviewer points out, German and Italian vary greatly as far as word order is concerned: Italian is an SVO language and German an SOV language (as visible in subordinate clauses) that, in addition, is characterized by the verb-second rule in main declarative and interrogative clauses. Independently from this fact, in both languages anche can be merged in the same portion of the clause (the TP); in these cases, the difference between Italian and German does not concern the position of anche/auch, but that of other constituents, notably the verb (which is usually analysed as occupying T in Italian and C in German) and the subject. |

| 9 | The DA is between square brackets, and the set of alternatives is marked by braces. |

| 10 | In other works, De Cesare (see, e.g., De Cesare 2008) uses the term avverbi paradigmatizzanti, which relates to the “paradigm”, i.e., the set of items/alternatives focus adverbs refer to. In the present contribution, we use the term additive adverb/particle, which refers to the basic additive semantics of these elements. |

| 11 | The same holds for pure, which is another additive particle of Italian but is less used and is characterized by a strong regional variation (see Treccani https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/pure/ accessed on 17 October 2022 and Ricca (2017), in particular, notes 1 and 2). |

| 12 | When auch bears the focus accent, the term focalizer turns out to be inappropriate since auch does not take scope over the focus of the sentence but constitutes the focus itself. |

| 13 | With regard to accented auch, Moroni and Bidese (2021b) recently put forward the hypothesis that it could be analysed as an accented modal particle similar to accented doch, ja and schon (Gutzmann 2010, p. 125; Zimmermann 2018, p. 688) operating on the whole proposition highlighting its truth value and thus conveying a verum focus-like effect. |

| 14 | De Cesare (2004, p. 193) gives the following examples taken from the Italian dictionary of Sabatini and Coletti (1997) (see also Bidese et al. 2019, pp. 246–48):

|

| 15 | Example (19) is the only one we found in the literature. In the LIP corpus, we found 4 instances of modal anche. In all 4 occurrences, anche appears in the postverbal position in a declarative clause, for ex. in (i)

|

| 16 | Scalar particles (such as even in English) impose a ranking of likely and less likely utterances (or entities) in a given context. For example, in “Even Jane called”, even implies not only that Jane has to be added to a list of people who called (additive value), but also that Jane is an unlikely or unexpected member of this list (scalar value), see, e.g., König (1991). |

| 17 | Benazzo and Dimroth (2015) also discuss anche, compared with its counterparts in German, French and Dutch; however, the Italian data they discuss only come from L1 speakers, while French is the language chosen to represent L2 Romance. Since the French aussi (“also”) behaves in a very different way than Italian anche, their results cannot be taken as a starting point for our analysis. |

| 18 | This video clip was originally developed to elicit material about the acquisition of finiteness (Dimroth 2012). |

| 19 | Note that, of course, these predictions are just speculations since we are well aware that L2 speakers and heritage speakers are two distinct populations that have different mental representations of the non-dominant language. Therefore, here we are not claiming at all that they should be considered on a par; our predictions are just a useful starting point to orientate our analysis. |

| 20 | Note that, coherently with our position on adult heritage languages as independent from the homeland standard language, we do not label the uses of IHSs as “target/non-target like”, because it would be improper to consider their production as having the rules of standard Italian as reference. Therefore, we prefer to define IHSs’ production as “compatible/incompatible”, “deviant/not deviant” or “matching/not matching” with the rules of HomIt (see also Note 5). |

| 21 | https://www.volip.it/ (accessed on 1 November 2022). For a description of the LIP corpus see De Mauro et al. (1993); Voghera et al. (2014). |

| 22 | Both the conversations of the LIP and the HABLA corpus were transcribed with a minimal level of annotation. In both corpora, the hash key stands for a pause. In the LIP transcriptions, no punctuation marks are used except for the question mark. In the HABLA data, the punctuation marks dot, question mark, and exclamation mark are used but no commas. Words without semantic content, such as interjections, are preceded by the symbol “&”, such as “&ehm”. The interruption of a speaker’s utterance by another speaker is marked by “+/”, self interruption is indicated by “+”. |

| 23 | In absolute numbers, this amounts to 20 out of 22 occurrences, 47 out of 47 and 7 out of 8, respectively. |

| 24 | Unfortunately, the HABLA corpus does not offer precise sociolinguistic data about the informants. However, various pieces of information can be extracted from the interviews themselves. As far as we can tell from these interviews, there do not seem to be important biographic differences between the six speakers, which seems to point to the fact that individual sensitivity plays an important role. However, since there are no full data, our biographical observations have to remain at an anecdotal level. |

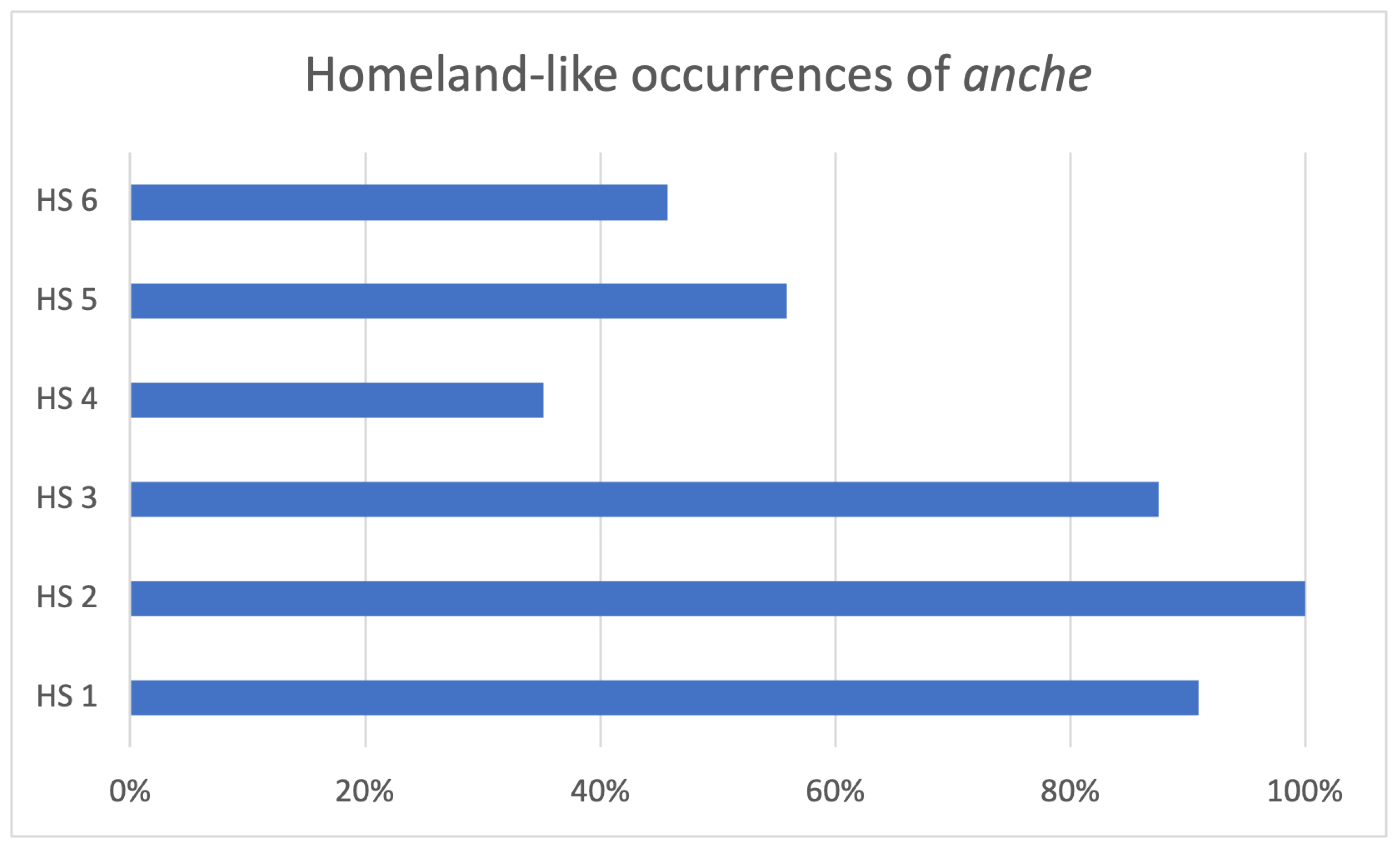

| 25 | From now on, all the figures and percentages only refer to HS4–HS6; with “corpus”, we refer just to all the occurrences of anche in the speech of these three informants, excluding HS1–HS3, which have shown to have a different grammar. |

| 26 | Here we do not consider truncated or root clauses, which are typical for an oral register, but are often difficult to classify. |

| 27 | Note that another difficulty for the HS concerns the fact that when the sentence is negated as in this case, the form neanche (“not even, not either”) is used in HomIt instead of the anche used by the IHS. |

| 28 | One anonymous reviewer pointed out that the use of anche in ex. (39) might not be excluded in native speech. As this use is not attested in our LIP control-corpus and it is ungrammatical according to our judgement as native speakers of Italian, we classified it as not part of the HomIt grammar. However, we believe that the status of examples such as (39) still needs to be further investigated in future research. |

| 29 | As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, this kind of “exemplifying/illustrative” anche could possibly have an additive-scalar value signalling that architecture is less expected in the scale of possible subjects one might take a picture of (i.e., photographing people is more obvious/expectable than photographing buildings). |

| 30 | An anonymous reviewer holds that in this example anche is used as an additive particle (with la carne in its scope), as the speaker is listing the things he likes to eat by adding carne (“meat”) to the list. However, in our view, the whole utterance come sa la carne is in the given context in the scope of anche (and not only la carne) as the previous text does not refer to the tastes of food. For this reason, we classified this instance as connective. |

| 31 | Glosses and translations are by the authors. |

| 32 | This is confirmed by some Google searches, in which there are numerous occurrences of the order “DA anche V”. |

| 33 | Note that this construction is also grammatical in German, but only when the DA is postverbal. Crucially, in HomIt and in HerIt we find this order mainly with preverbal DAs. |

| 34 | We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out this aspect to us. |

| 35 | |

| 36 | Note that in this analysis, the subject constituting the DA of anche might be in TP or in CP; if the second is the case, we could speculate that IHSs have transferred a V2 rule from German to HerIt (as suggested by Alessandra Tomaselli, p.c.). Unfortunately, our corpus does not contain decisive evidence in favour or against this hypothesis; in fact, there are V3 orders that would be incompatible with a strict V2 language such as German, so that an eventual V2 property in HerIt would be at most optional, or “relaxed” (unless they are considered as production errors). In addition, we could not find evidence for the XVS order, which is considered typical of V2 languages. In any case, more research is needed to give a definitive answer to this topic. |

References

- Andorno, Cecilia, and Anna-Maria De Cesare. 2017. Mapping additivity through translation. From French aussi to Italian anche and back in the Europarl-direct corpus. In Focus on Additivity. Adverbial Modifiers in Romance, Germanic, and Slavic Languages. Edited by Anna-Maria De Cesare and Cecilia Andorno. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 157–200. [Google Scholar]

- Andorno, Cecilia, and Giuseppina Turco. 2015. Embedding additive particles in the sentence information structure: How L2 learners find their way through positional and prosodic patterns. Linguistik Online 71: 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andorno, Cecilia. 2000. Focalizzatori fra Connessione e Messa a Fuoco. Milano: Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Andorno, Cecilia. 2008. Ancora su anche, anche su ancora. Per uno studio comparativo dell’apprendimento e della gestione di strategie coesive in L2, Diachronica et Synchronica. Studi in onore di Anna Giacalone Ramat. Edited by Romano Lazzeroni, Emanuele Banfi, Giuliano Bernini, Marina Chini and Giovanna Marotta. Pisa: ETS Edizioni, pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, Adriana. 2004. Aspects of the low IP area. In The Structure of CP and IP. The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Luigi Rizzi. New York: Oxford University Press, vol. 2, pp. 16–51. [Google Scholar]

- Benazzo, Sandra, and Christine Dimroth. 2015. Additive particles in Romance and Germanic languages: Are they really similar? Linguistik Online 71: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benincà, Paola, and Cecilia Poletto. 2004. Topic, Focus and V2: Defining the CP Sublayers. In The Structure of IP and CP: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Luigi Rizzi. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 52–75. [Google Scholar]

- Benincà, Paola. 1985–1986. L’interferenza sintattica: Di un aspetto della sintassi ladina considerato di origine tedesca. Quaderni Patavini di Linguistica 5: 3–15, [Reprinted in Benincà, Paola. 1994. La Variazione Sintattica. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 89–104]. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, Jan Casalicchio, and Patrizia Cordin. 2016. Il ruolo del contatto tra varietà tedesche e romanze nella costruzione “verbo più locativo”. Vox Romanica 75: 116–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, Jan Casalicchio, Manuela Caterina Moroni, and Alessandro Parenti. 2019. The expression of additivity in the Alps: German auch, Italian anche and their counterparts in Gardenese Ladin. In La Linguistica Vista Dalle Alpi/Linguistic Views from the Alps/Teoria Lessicografia e Multilinguismo/Language Theory, Lexicography and Multilinguism. Edited by Ermenegildo Bidese, Jan Casalicchio and Manuela Caterina Moroni. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 339–70. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2021. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Program], Version 6.2.14; September. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Büring, Daniel. 1997. The Meaning of Topic and Focus. The 59th Street Bridge Accent. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Caloi, Irene. 2017. Additive focus particles in German-speaking learners of Italian as L2. In Focus on Additivity. Adverbial Modifiers in Romance, Germanic, and Slavic Languages. Edited by Anna-Maria De Cesare and Cecilia Andorno. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 237–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna. 2011. German and Italian modal particles and clause structure. The Linguistic Review 28: 493–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalicchio, Jan, and Andrea Padovan. 2019. Contact-induced phenomena in the Alps. In Italian Dialectology at the Interface. Edited by Silvio Cruschina, Adam Ledgeway and Eva Maria Remberger. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 237–55. [Google Scholar]

- Casalicchio, Jan, and Federica Cognola. 2023. On the Syntax of Fronted Adverbial Clauses in Two Tyrolean Dialects: The Distribution of Resumptive Semm. In Adverbial Resumption in Verb Second Languages. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 113–44. [Google Scholar]

- Casalicchio, Jan, and Federica Cognola. Forthcoming. Microvariation in the distribution of resumptive D-pronouns in two Tyrolean dialects of Northern Italy. Languages 8.

- Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on Governing and Binding. The Pisa Lectures. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 1990. Types of A-Bar Dependencies. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 2020. The Syntax of Relative Clauses: A Unified Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cognola, Federica, Manuela Caterina Moroni, and Ermenegildo Bidese. 2022. A comparative study of German auch and Italian anche. In Particles in German, English, and Beyond. Edited by Gergel Remus, Ingo Reich and Augustin Speyer. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 209–42. [Google Scholar]

- Coniglio, Marco. 2008. Modal particles in Italian. University of Venice Working Papers in Linguistics 18: 91–129. [Google Scholar]

- De Cesare, Anna-Maria. 2004. L’avverbio anche e il rilievo informativo del testo. In La lingua nel testo, il testo nella lingua. Edited by Angela Ferrari. Torino: Istituto dell’Atlante Linguistico Italiano, pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- De Cesare, Anna-Maria. 2008. Gli avverbi paradigmatizzanti. In L’interfaccia Lingua-testo. Natura e Funzioni Dell’articolazione Informativa Dell’enunciato. Edited by Angela Ferrari, Luca Cignetti, Anna-Maria De Cesare, Letizia Lala, Magda Mandelli, Claudia Ricci and Carlo Enrico Roggia. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, pp. 340–61. [Google Scholar]

- De Cesare, Anna-Maria. 2015. Additive focus adverbs in canonical word orders. A corpus-based study of It. anche, Fr. aussi and E. also in written news. Linguistik Online 71: 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cesare, Anna-Maria. 2019. Le Parti Invariabili del Discorso. Roma: Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- De Mauro, Tullio, Federico Mancini, and Miriam Voghera. 1993. Lessico di Frequenza Dell’italiano Parlato. Milano: Etaslibri. [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth, Christine, and Norbert Dittmar. 1998. Auf der Suche nach Steuerungsfaktoren für den Erwerb von Fokuspartikeln: Längsschnittbeobachtungen am Beispiel polnischer und italienischer Lerner des Deutschen. In Eine zweite Sprache lernen. Empirische Untersuchungen zum Zweitspracherwerb. Edited by Heide Wegener. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 217–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth, Christine, Cecilia Andorno, Sandra Benazzo, and Josje Verhagen. 2010. Given claims about new topics. How Romance and Germanic speakers link changed and maintained information in narrative discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 42: 3328–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimroth, Christine. 2004. Fokuspartikeln und Informationsgliederung im Deutschen. Tübingen: Stauffenburg. [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth, Christine. 2006. The Finite Story. Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. Available online: https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/islandora/object/lat%3A1839_00_0000_0000_0008_8C95_3 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Dimroth, Christine. 2012. Videoclips zur Elizitation von Erzählungen: Methodische Überlegungen und einige Ergebnisse am Beispiel der “Finite Story”. In Einblicke in die Zweitspracherwerbsforschung und ihre methodischen Verfahren. Edited by Bernt Ahrenholz. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fenyvesi, Anna. 2005. Hungarian in the United States. In Hungarian Language Contact Outside Hungary: Studies on Hungarian as a Minority Language. Edited by Anna Fenyvesi. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 265–318. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee, Fred. 2022. The monolingual bias. A critical analysis. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 10: 153–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewendorf, Günther. 2008. The left clausal periphery: Clitic left-dislocation in Italian and left-dislocation in German. In Dislocated Elements in Discourse: Syntactic, Semantic, and Pragmatic Perspectives. Edited by Benjamin Shaer, Philippa Cook, Werner Frey and Claudia Maienborn. London: Routledge, pp. 49–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gutzmann, Daniel. 2010. Betonte Modalpartikeln und Verumfokus. In 40 Jahre Partikelforschung. Edited by Elke Hentschel and Theo Harden. Tübingen: Stauffenburg, pp. 119–38. [Google Scholar]

- Helmer, Henrike. 2016. Analepsen in der Interaktion. Semantische und sequenzielle Eigenschaften von Topik-Drop im gesprochenen Deutsch. Heidelberg: Winter. [Google Scholar]

- Hulk, Aafke, and Natascha Müller. 2000. Bilingual first language acquisition at the interface between syntax and pragmatics. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 3: 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayne, Richard. 1996. Microparametric syntax: Some introductory remarks. In Microparametric Syntax and Dialect Variation. Edited by James R. Black and Virginia Motapanyane. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. ix–xviii. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard. 2005. Some notes on comparative syntax, with special reference to English and French. In Handbook of Comparative Syntax. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque and Richard Kayne. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmer, Agnes. 2012. Pronomina und Pronominalklitika im Cimbro. Untersuchungen zum grammatischen Wandel einer deutschen Minderheitensprache in romanischer Umgebung. Stuttgart: Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- König, Ekkehard. 1991. The Meaning of Focus Particles: A Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, Manfred. 1998. Additive particles under stress. In SALT VIII, Paper presented at 8th Semantics and Linguistic Theory Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, May 8–10. Edited by Devon Strolovitch and Aaron Lawson. Ithaca: Cornell University, pp. 111–29. Available online: https://journals.linguisticsociety.org/proceedings/index.php/SALT/article/view/2799/2539 (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Maria Polinsky. 2022. Language history on fast forward: Innovations in heritage languages and diachronic change. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 25: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja, Dagmar Barton, Giulia Bianchi, and Ilse Stangen. 2012. The HABLA-corpus (German-French and German-Italian). In Multilingual Corpora and Multilingual Corpus Analysis. Edited by Schmidt Thomas and Kai Wörner. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 163–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja, Dagmar Barton, Katja Hailer, Ewgenia Klaschik, Ilse Stangen, Tatjana Lein, and Joost van de Weijer. 2014. Foreign accent in adult simultaneous bilinguals. Heritage Language Journal 11: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja, Fatih Bayram, and Jason Rothman. 2017. Terminology matters II. Early bilinguals show cross-linguistic influence but are not attriters. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 7: 719–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2011. Hamburg Adult Bilingual Language. Archived in Hamburger Zentrum für Sprachkorpora, Version 0.2; June 30. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11022/0000-0000-5C64-9 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Lloyd-Smith, Anika, Marieke Einfeldt, and Tanja Kupisch. 2020. Italian-German bilinguals: The effects of heritage language use in early acquired languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 24: 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbner, Sebastian. 1990. Wahr neben Falsch. Duale Operatoren als die Quantoren natürlicher Sprache. Tübingen: Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Moroni, Manuela Caterina, and Ermenegildo Bidese. 2021a. Deutsches auch und italienisches anche im Vergleich. Gemeinsame Funktion und sprachspezifischer Gebrauch. Linguistik Online 111: 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, Manuela Caterina, and Ermenegildo Bidese. 2021b. Zur Fokussierung der Modalpartikel auch. Talk at the Festkolloquium zum Anlass des 60. Geburtstags von Helmut Weiß. 12.11.2021. Frankfurt am Main: University of Frankfurt am Main. [Google Scholar]

- Moroni, Manuela Caterina. 2010. Modalpartikeln Zwischen Syntax, Prosodie und Informationsstruktur. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Natascha, and Aafke Hulk. 2001. Cross-linguistic influence in bilingual language acquisition: Italian and French as recipient languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 4: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Sonja. 2014. Modalpartikeln. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, Naomi. 2016. Heritage languages as new dialects. In The Future of Dialects. Edited by Marie-Hélène Côté, Remco Knooihuizen and John Nerbonne. Berlin: Language Science Press, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nederstigt, Ulrike. 2003. Auch and noch in Child and Adult German. Berlin: New York: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, Dennis. 2014. An ellipsis approach to contrastive left-dislocation. Linguistic Inquiry 45: 269–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasch, Renate, Ursula Brauße, Eva Breindl, and Ulrich Hermann Waßner. 2003. Handbuch der Deutschen Konnektoren. Berlin: De Gruyter, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Platzack, Christer. 2001. The vulnerable C-domain. Brain and Language 77: 364–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2018. Heritage Languages and Their Speakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, Laura, and Christine Dimroth. 2021. Added alternatives in spoken interaction: A corpus study on German auch. Languages 6: 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, Davide. 2017. Meaning both ‘also’ and ‘only’? The intriguing polysemy of Old Italian pur(e). In Focus on Additivity. Adverbial Modifiers in Romance, Germanic and Slavic Languages. Edited by Anna-Maria De Cesare and Cecilia Andorno. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 45–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of Grammar. Edited by Liliane Haegeman. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 281–337. [Google Scholar]

- Romaine, Suzanne. 1995. Bilingualism. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, Jason. 2009. Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, Francesco, and Vittorio Coletti. 1997. DISC: Dizionario Italiano Sabatini Coletti. Firenze: Giunti. [Google Scholar]

- Sansò, Andrea. 2020. I Segnali Discorsivi. Roma: Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Seliger, Herbert W. 1996. Primary language attrition in the context of bilingualism. In Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Edited by William C. Ritchie and Tej K. Bhatia. New York: Academic Press, pp. 605–25. [Google Scholar]

- Serratrice, Ludovica, and Antonella Sorace. 2009. Internal and external interfaces in bilingual language development: Beyond structural overlap. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1994. Language Contact and Change: Spanish in Los Angeles. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2004. Native language attrition and developmental instability at the syntax-discourse interface: Data, intepretations and methods. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 143–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurmair, Maria. 1989. Modalpartikeln und ihre Kombinationen. Tübingen: Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Tsimpli, Ianthi-Maria, and Antonella Sorace. 2006. Differentiating interfaces: L2 performance in syntax-semantics and syntax-discourse phenomena. In BUCLD 30: Proceedings of the 30th annual Boston University Conference on Language Development: In Honor of Lydia White, Boston, Morocco, 4–6 November 2005. Edited by David Bamman, Tatiana Magnitskaia and Colleen Zaller. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 653–64. [Google Scholar]

- Uhmann, Susanne. 1991. Fokusphonologie. Tübingen: Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijswijk, Remy, Antje Muntendam, and Ton Dijkstra. 2017. Focus marking in Dutch by heritage speakers of Turkish and Dutch L1 speakers. Journal of Phonetics 61: 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voghera, Miriam, Claudio Iacobini, Renata Savy, Francesco Cutugno, Aurelio De Rosa, and Iolanda Alfano. 2014. VoLIP: A Searchable Corpus of Spoken Italian. In Complex Visibles Out There. Proceedings of the Olomouc Linguistics Colloquium 2014: Language Use and Linguistic Structure. Edited by Veselovská and Markéta Janebová. Olomouc: Palacký University, pp. 627–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, Malte. 2018. Wird schon stimmen! A Degree Operator Analysis of Schon. Journal of Semantics 35: 687–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Function | Properties | Auch | Anche |

|---|---|---|---|

| additive particle | Particle + DA (left adjacency) | + | + |

| Postverbal DA+ accented particle (right adjacency) | + | - | |

| Preverbal DA+ accented particle (right adjacency) | - | ? | |

| DA+V+ accented particle (discontinuous construction) | + | - | |

| connective | Syntactically integrated in the postverbal position | + | + |

| Syntactically integrated in the first position | + | - | |

| Syntactically non-integrated (parenthetical use) | - | + | |

| modal particle | Syntactically integrated in the postverbal position (declaratives and exclamatives) | + | + |

| Syntactically integrated in the postverbal position (other sentence types) | + | - |

| Speaker’s Code | Abbreviation | Total Number of Occurrences of Anche |

|---|---|---|

| D11_2L1_DI_HAN_INT_it | HS1 | 22 |

| D10_2L1_DI_ANL_INT_it | HS2 | 47 |

| D05_2L1_DI_PAS_INT_it | HS3 | 8 |

| D01_2L1_DI_GIH_INT_it | HS4 | 54 |

| D03_2L1_DI_MAL_INT_it | HS5 | 34 |

| D14_2L1_DI_PHI_INT_it | HS6 | 35 |

| Total instances | 200 |

| Uses of Anche | Matching HomIt | Non-Matching HomIt | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive particle | 39 | 33 | 72 |

| Sentence connective | 13 | 10 | 23 |

| Modal particle | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Other cases | / | 23 | 23 |

| Total instances | 54 | 69 | 123 |

| Pattern | Occurrences | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| “HomIt Pattern”: [anche DA] (Anche Gianni dorme. “Also Gianni sleeps.”) | 44 | 61.1% |

| Pattern 1: [DA anche] (Gianni anche dorme. “Gianni also sleeps.”) | 9 | 12.5% |

| Pattern 2: discontinuous construction (Gianni dorme anche. “Gianni sleeps also.”) | 13 | 18.1% |

| Pattern 3: DA is dropped (topic drop) (__ dorme anche. “__ sleeps also.”) | 4 | 5.6% |

| others | 2 | 2.8% |

| Total | 72 | 100% |

| Role of the DA | Cases in Which the Additive Particle Is Used Differently Than in HomIt | Total Number of Instances |

|---|---|---|

| Subject | 64% | 22 |

| Direct object | 40% | 10 |

| PP | 33.3% | 21 |

| VP | 25% | 8 |

| other | 58% | 11 |

| Total | 46% | 72 |

| Position of Anche | Number of Occurrences | Percentage | Cases Matching HomIt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preverbal anche | 17 | 23.6% | 12 |

| anche DA V | 12 | 12 | |

| DA anche V | 5 | 5 (marg.) | |

| Postverbal anche | 47 | 65.3% | 21 |

| DA V anche | 13 | 0 | |

| V anche DA | 17 | 15 | |

| V DA anche | 4 | 0 | |

| V X anche DA | 9 | 6 | |

| (DA) V anche (topic drop) | 4 | 0 | |

| Elliptical clauses (without V) | 7 | 9.7% | 6 |

| others | 1 | 1.4% | 0 |

| TOTAL | 72 | 100% | 39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casalicchio, J.; Moroni, M.C. The Syntax–Pragmatics Interface in Heritage Languages: The Use of anche (“Also”) in German Heritage Speakers of Italian. Languages 2023, 8, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020104

Casalicchio J, Moroni MC. The Syntax–Pragmatics Interface in Heritage Languages: The Use of anche (“Also”) in German Heritage Speakers of Italian. Languages. 2023; 8(2):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020104

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasalicchio, Jan, and Manuela Caterina Moroni. 2023. "The Syntax–Pragmatics Interface in Heritage Languages: The Use of anche (“Also”) in German Heritage Speakers of Italian" Languages 8, no. 2: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020104

APA StyleCasalicchio, J., & Moroni, M. C. (2023). The Syntax–Pragmatics Interface in Heritage Languages: The Use of anche (“Also”) in German Heritage Speakers of Italian. Languages, 8(2), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020104