A Phonological Study of Rongpa Choyul

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Syllable Canon

3. Onsets

3.1. Simple Consonant Initials

- Rongpa obstruents (i.e., plosives, affricates, and fricatives) show a three-way contrast between voiceless unaspirated, voiceless aspirated, and voiced. It is noteworthy that Rongpa has contrastive aspirated fricatives, which is rather rare cross-linguistically. The minimal or near-minimal triplets in (1) illustrate the distinctions:8

| (1) | /p/ | /poH/ ‘to dig: 1sg’ | /t/ | /toʁH/ ‘wing’ |

| /pʰ/ | /pʰoH/ ‘to worship: 1sg’ | /tʰ/ | /tʰoʁH/ ‘meat; flesh’ | |

| /b/ | /buH/ ‘breath’ | /d/ | /doʁL/ ‘to saw: 1sg’ | |

| /ts/ | /tsoH/ ‘to sit: 1sg’ | /ʧ/ | /ʧoL/ ‘to wear (ring): 1sg’ | |

| /tsʰ/ | /tsʰoH/ ‘to dye: 1sg’ | /ʧʰ/ | /ʧʰoH/ ‘to eat: 1sg’ | |

| /dz/ | /dzoH/ ‘to teach: 1sg’ | /ʤ/ | /ʤoH/ ‘to run: 1sg’ | |

| /tʂ/ | /tʂəH/ ‘this’ | /k/ | /kɘH/ ‘age’ | |

| /tʂʰ/ | /tʂʰəH NbuH/ ‘buttocks’ | /kʰ/ | /kʰɘH/ ‘to need’ | |

| /dʐ/ | /dʐəH/ ‘to ruminate (animals)’ | /ɡ/ | /ɡɘH/ ‘vulture’ | |

| /s/ | /seH NbeH/ ‘cotton’ | /ʃ/ | /ʃɘH/ ‘iron spoon’ | |

| /sh/ | /sʰeL/ ‘firewood’ | /ʃʰ/ | /ʃʰɘH/ ‘worship’ | |

| /z/ | /zeL/ ‘liver’ | /ʒ/ | /ʒɘH/ ‘to move’ | |

| /ʂ/ | /ʂɜL wuH/ ‘weed’ | |||

| /ʂʰ/ | /ʂʰɜL wuH/ ‘money’ | |||

| /ʐ/ | /ʐɜL/ ‘travel-ready dishes’ |

- 2.

- Affricates and fricatives show a three-way contrast in their places of articulation (i.e., alveolar, postalveolar, and retroflex):

| (2) | /ts/ | /tsəH/ ‘to squeeze: 1pl’ | /tsʰ/ | /tsʰəʁH/ ‘thorn’ |

| /ʧ/ | /ʧəL ʧəH paʶL/ ‘cicada’ | /ʧʰ/ | /ʧʰəʁL ʧʰəʁH/ ‘sweet’ | |

| /tʂ/ | /tʂəH/ ‘this’ | /tʂʰ/ | /tʂʰəʁL tʂʰəʁH/ ‘be pleasant’ | |

| /s/ | /səL/ ‘nit’ | /dz/ | /dzɛH/ ‘to teach: 1pl’ | |

| /ʃ/ | /ʃəH/ ‘cypress’ | /ʤ/ | /ʤɛH/ ‘to run: 1pl’ | |

| /ʂ/ | /ʂəH/ ‘louse’ | /dʐ/ | /dʐɛH/ ‘enemy’ |

- 3.

- Voiced nasals and liquids show contrasts with their voiceless counterparts, though the occurrences of voiceless nasals and liquids are rare, as minimal pairs in (3) show:

| (3) | /m/ | /maʶH xkaʶL/ ‘rainbow’ | /n/ | /neL/ ‘you’ |

| /m̥/ | /m̥aʶL/ ‘eared pheasant’ | /n̥/ | /n̥eH n̥eL/ ‘red’ | |

| /ŋ/ | /ŋɜL/ ‘I’ | /l/ | /leH/ ‘earth; ground’ | |

| /ŋ̊/ | /ŋ̊ɜʶH/ ‘gold’ | /l̥/ | /l̥eH l̥eL/ ‘be thick’ | |

| /r/ | /roH/ ‘to see: 1sg’ | |||

| /r̥/ | /r̥oL/ ‘to tear down: 1sg’ |

- 4.

- Rongpa contrasts retroflex fricative /ʐ/ and the trill /r/. Consider these minimal pairs in (4):

| (4) | /r/ | /rəL/ ‘mountain’ | /wɜL rəH/ ‘bear’ |

| /ʐ/ | /ʐəL/ ‘water’ | /wɜL ʐəH/ ‘farm cattle’ |

- 5.

- Voiced labiodental fricative /v/ and labial-velar approximant /w/ are contrastive:

| (5) | /w/ | /wɜL ʐəH/ ‘farm cattle’ | /wɛL/ ‘to bake: 1pl’ |

| /v/ | /vɜH/ ‘tsampa’ | /kəL vɛH/ ‘to shake: 1pl’ |

- 6.

- Alveolar nasals /n̥/ and /n/ are realized as a palatal nasal [ɲ̊] and [ɲ], respectively, when followed by the vowels /e, ɛ, o/. In other words, palatal nasals can be observed among the surface forms, but they are not phonemic. Consider the examples below:

| (6) | /nɛL/→[ɲɛL] ‘fish’ /n̥oL/→[ɲ̊oL] ‘fried barley’ /n̥eH n̥eL/→[ɲ̊eH ɲ̊eL] ‘red’ |

- 7.

- Velar consonants retract to uvular when the nuclei of the syllable is a uvularized vowel, e.g.,

| (7) | /koʶL/→[qoʶL] ‘valley’ /kʰoʶH/→[qʰoʶH] ‘head’ /xoʶL/→[χoʶL] ‘to wear (necklace): 1sg’ /ɣoʶL/→[ʁoʶL] ‘lunatic’ |

- 8.

- The two rather marginal phonemes are: a labio-dental voiceless fricative /f/, only observed in /paʶL feH/ ‘soda’, and a voiceless velar nasal /ŋ̊/, only observed in /ŋ̊ɜʶH/ ‘gold’.

3.2. Consonant Clusters as Complex Initials

3.2.1. C1 = Dorsal Fricative /x/ or /ɣ/

- The first element /x/ and /ɣ/ are contrastive before voiced nasals and laterals, which is attested by the following minimal pairs in (8):

| (8) | /xm/ | /xmɜH/ ‘crupper-strap’ | /xn/ | /xniH/ ‘nose’10 |

| /ɣm/ | /ɣmɜH/ ‘mushroom’ | /ɣn/ | /ɣniH/ ‘ear’11 | |

| /xŋ/ | /xŋiL/ ‘be skewed’ | /xl/ | /xliH/ ‘tongue’ | |

| /ɣŋ/ | /ɣŋiH/ ‘drum’ | /ɣl/ | /ɣliH/ ‘hilt (of knife)’ |

- 2.

- In Rongpa, “/x/+voiced sonorants” clusters are not variants of voiceless sonorants. As shown in the following examples in (9), these initials are contrastive.

| (9) | /m̥/ | /m̥ɜH/ ‘person’ | /n̥/ | /n̥ɜL n̥ɜH/ ‘green; blue’ |

| /xm/ | /xmɜH/ ‘crupper-strap’ | /xn/ | /xnɜH NbɜL/ ‘mouth’ | |

| /ŋ̊/ | /ŋ̊ɜʶH/ ‘gold’ | /l̥/ | /l̥aʁH/ ‘wind’ | |

| /xŋ/ | /xŋɜʶL/ ‘parrot’ | /xl/ | /xlaʁH/ ‘white poplar’ |

- 3.

- In Rongpa, voiceless aspirated fricatives are phonemic. Note that in Khanggsar (Kǒngsè孔色) Stau (a Rgyalrongic language spoken in a neighboring area), voiceless fricatives are realized with aspiration in simplex initial position, and as unaspirated when they are a component of a complex initial (Jacques et al. 2017, p. 598). However, this is not the case in Rongpa. In this language, voiceless fricatives still contrast in aspiration when preceded by /x/ as C1, as minimal pairs in (10) show:

| (10) | /xs/ | /xsɜʶL xsɜʶH/ ‘be long’ | /xʃ/ | /xʃəʶH xʃəʶH/ ‘be wide’ |

| /xsʰ/ | /xsʰɜʶL xsʰɜʶH/ ‘be sharp’ | /xʃʰ/ | /xʃʰəʶH/ ‘to break off: 1pl’ | |

| /xʂ/ | /xʂɜʶL xʂəʶH/ ‘to twist’ | |||

| /xʂʰ/ | /xʂʰəH/ ‘to drive away’ |

- 4.

- The allophones of C1 = /x/ and /ɣ/

- ①

- Uvular allophones [χ] and [ʁ]

| (11) | /xpoʁH/→[χpoʁH] ‘ice’ /xpəʁH/→[χpəʁH] ‘to blow: 1pl’ /xpeʶH/→[χpeʶH] ‘official; leader’ /xpɜʶH/→[χpɜʶH] ‘goiter; pus’ /xpaʁL/→[χpaʁL] ‘toad’ | /ɣnoʶH/→[ʁnoʶH] ‘to read: 1sg’ /ɣnəʁH/→[ʁnəʁH] ‘to read: 1pl’ /ɣneʶL/→[ʁneʶL] ‘to grind’ /ɣnɜʶH/→[ʁnɜʶH] ‘brain’ /ɣnaʶH/→[ʁnaʶH] ‘weed’ |

- ②

- Free variation: [x] or [ʂ]

| (12) | /xteH/→[xteH]~[ʂteH] ‘mat’ /xtʂɛH/→[xtʂɛH]~[ʂtʂɛH] ‘crupper-strap’ /xkuL xniH/→[xkuL xniH]~[ʂkuL xniH] ‘toe’ |

- ③

- Social/contextual variation in /ɣ/:

| (13) | /ɣniH/→[ʕɾniH] ‘ear’ /ɣnɜH/→[ʕɾnɜH] ‘tail’ |

- 5.

- The phonemic status of the first elements /x/ and /ɣ/ is attested by many lexical pairs that are minimally distinguished by the existence or absence of C1:

| (14) | /p/ | /paʁL/ ‘be deaf’ | /pʰ/ | /pʰoʁH/ ‘to splash: 1sg’ |

| /xp/ | /xpaʁL/ ‘toad’ | /xpʰ/ | /xpʰoʁL/ ‘to cover: 1sg’ | |

| /m/ | /meH/ ‘to name’ | /t/ | /toʁH/ ‘wing’ | |

| /xm/ | /xmeH/ ‘medicine’ | /xt/ | /xtoʁH/ ‘sink; Tibetan silver’ | |

| /x/ | /tʰɘH/ ‘cereal (barley and wheat)’ | /d/ | /dəʁL/ ‘to saw: 1pl’ | |

| /xt/ | /xtʰɘH/ ‘to stampede’ | /ɣd/ | /ɣdəʁH/ ‘umbrella’ | |

| /ts/ | /tsəʁH/ ‘grate’ | /tsʰ/ | /tsʰaʁH paʁL/ ‘wink; blink’ | |

| /xts/ | /xtsəʁH/ ‘ecphyma’ | /xtsʰ/ | /xtsʰaʁH/ ‘cough [N]’ | |

| /dz/ | /dzəʁL/ ‘to thread: 1pl’ | /z/ | /zoʁH/ ‘woman; daughter’ | |

| /ɣdz/ | /ɣdzəʁH/ ‘pillar’ | /ɣz/ | /ɣzoʁL/ ‘storage container’ | |

| /s/ | /sɜʶL piH/ ‘be new’ | /n/ | /naʁH laʁL/ ‘leaf’ | |

| /xs/ | /xsɜʶL xsɜʶH/ ‘be long’ | /xn/ | /xnaʁL/ ‘nettle’ | |

| /l/ | /kʰeH ləH/ ‘spleen’ | /ʧ/ | /ʧɛL bʒɛH/ ‘clay teapot’ | |

| /xl/ | /xləL/ ‘birch’ | /xʧ/ | /xʧɛL bʒɛH/ ‘shovel’ | |

| /ʧʰ/ | /ʧʰəʁL ʧʰəʁH/ ‘be sweet’ | /tʂ/ | /tʂuL/ ‘village’ | |

| /xʧʰ/ | /xʧʰəʁH/ ‘dog’ | /xtʂ/ | /xtʂuH mɘH/ ‘beggar’ | |

| /tʂʰ/ | /tʂʰəʁL tʂʰəʁH/ ‘be pleasant’ | /ʂ/ | /ɣoʁL ʂaʁH/ ‘peach tree’ | |

| /xtʂʰ/ | /xtʂʰəʁH/ ‘to carry (in arms): 1pl’ | /xʂ/ | /xʂaʁL/ ‘soil’ | |

| /ʂʰ/ | /ʂʰɜH/ ‘strength’ | /ʐ/ | /ʐɜL/ ‘travel-ready dishes’ | |

| /xʂʰ/ | /xʂʰɜH/ ‘to drive (cattle): 1sg’ | /ɣʐ/ | /ɣʐɜH/ ‘fertilizer (excrements)’ | |

| /k/ | /koL/ ‘porcupine’ | /kʰ/ | /kʰuH/ ‘corner’ | |

| /xk/ | /xkoL/ ‘to carry (on shoulder):1sg’ | /xkʰ/ | /xkʰuH/ ‘smoke’ | |

| /ɡ/ | /ɡeL/ ‘to like: 2pl’ | |||

| /ɣɡ/ | /moH ɣɡeL/ ‘old woman’ |

3.2.2. C1 = Nasal /m/ or /N/

- The abstract phoneme /N-/ is homorganic to the following consonant, which can be stated using this phonological rule:13

| (15) | /NphaʁL raʁH/→[mphaʁL raʁH] ‘to scratch’ /NtʰeH/→[ntʰeH] ‘to sing: 1sg’ /NkʰuL/→[ŋkʰuL] ‘to use’ |

- 2.

- C1 = /m/ and /N/ are contrastive before voiced plosives or affricates, as demonstrated by the examples in (16):

| (16) | /md/ | /mdaʶH/ ‘bow’ | /mdz/ | /mdzɜH / ‘room’ |

| /Nd/ | /aʶL NdaʶH/ ‘bull’ | /Ndz/ | /NdzɜH/ ‘to insert’ | |

| /mʤ/ | /mʤɜL/ ‘be sticky’ | /mdʐ/ | /mdʐɛH/ ‘rice’ | |

| /Nʤ/ | /NʤɜL/ ‘to change’ | /Ndʐ/ | /NdʐɛL bəH/ ‘fruit’ |

- 3.

- If it is preceded by /m/ and the nucleus is /ɛ/ or /aʁ/, C2 can be labialized (adding the features of [+labial] and [+round]). Related examples are:

| (17) | /mtʂʰaʁH/→[mtʂʰwaʁH] ‘plant ash’ /mdʐɛH/→[mdʐwɛH] ‘rice’ |

| (18) | /P-NtʰeH/→[mtʰeH] ‘he sings’ /P-NdʐəʶL/→[mdʐəʶL] ‘he arrests’ |

- 4.

- The ‘nasal + stop/affricate’ clusters can also be found across syllable boundaries. Syllable boundary readjustment has been applied, with original coda becoming part of the following onset. Many of the related examples are etymologically Tibetan loanwords. Examples are listed in Table 8:

- 5.

- The phonemic status of the first elements /N/ and /m/ is attested by these minimal pairs in (19):

| (19) | /ph/ | /phaʁH/ ‘to vomit’ | /b/ | /buH/ ‘breath’ |

| /Nph/ | /NphaʁL raʁH/ ‘to scratch’ | /Nb/ | /NboH/ ‘to protect:1sg’ | |

| /th/ | /tʰiH/ ‘big water tank’ | /d/ | /deH/ ‘to accumulate: 2pl’ | |

| /mth/ | /mtʰiL mtʰiH/ ‘be tall’ | /Nd/ | /NdeH/ ‘what’ | |

| /tsʰ/ | /ɡəL tsʰiH/ ‘vertebra’ | /dz/ | /dzɛH/ ‘to teach: 1pl’ | |

| /mtsʰ/ | /mtsʰiH/ ‘lake’ | /mdz/ | /mdzɛL/ ‘to soot’ | |

| /dz/ | /dzəʁH/ ‘to thread: 1pl’ | /n/ | /nɘL/ ‘forest’ | |

| /Ndz/ | /NdzəʁH/ ‘a unit of length’16 | /mn/ | /mnɘH/ ‘eye’ | |

| /ʧʰ/ | /ʧʰɜH ʧʰɜL/ ‘be thin’ | /ʤ/ | /ʤoH/ ‘to run: 1sg’ | |

| /mʧʰ/ | /mʧʰɜL mʧʰɜH/ ‘be pretty’ | /Nʤ/ | /NʤoL NʤoH/ ‘be weak (liquor)’ | |

| /tʂʰ/ | /tʂʰɜL/ ‘to cut’ | /dʐ/ | /dʐɛH/ ‘enemy’ | |

| /mtʂʰ/ | /mtʂʰɜH mtʂʰɜL/ ‘be skewed’ | /mdʐ/ | /mdʐɛH/ ‘rice’ | |

| /kʰ/ | /kʰuH/ ‘corner’ | /ɡ/ | /ɡuL/ ‘be freezing’ | |

| /Nkʰ/ | /NkʰuL/ ‘to use: 3’ | /Nɡ/ | /NɡuH NɡuL/ ‘to nod (head)’ |

3.2.3. C1 = Bilabial Fricative /p/ or /b/

- The phonemic status of the first element /p/ and /b/

| (20) | /pl/ | /ploL/→[ɸloL] ‘to plait: 1sg’ | /kʰoʁL plɘH/→[qʰoʁL ɸlɘH] ‘to unbraid hair’ |

| /bl/ | /bloH/→[βloH] ‘to do: 1sg’ | /koʁL blɘH/→[qoʁL βlɘH] ‘lightning’ |

- 2.

- Allophones of the first element /p/ and /b/

| (21) | /ptʂoʁH/→[ptʂoʁH] ‘bull’ /ptʂʰəʁH/→[ptʂʰəʁH] ‘tusk (of animals)’ /pʧəH pʧəL/→[pʧəH pʧəL] ‘temple ’ /bʤɜH→[bʤɜH] ‘be full’ /bʤuL /→[bʤuL] ‘to extend’ |

| (22) | /pʃaʁH/→[ɸʃaʁH] ‘honey’ /psɘH/→[ɸsɘH] ‘light’ /bʒeL/→[βʒeL] ‘scabbard’ /blaʁH/→[βlaʁH] ‘thigh’ /braʁH/→[βraʁH] ‘cow’ |

- 3.

- Analogy with /m/ discussed above; the first element /p/ also triggers labialization of the following consonant:

| (23) | /ptsaʶH/→[ptsʷaʶH] ‘rust’19 /ptʂɛL/→[ptʂʷɛL] ‘distiller’s yeast; friend; placenta’ /pʃaʶH/→[ɸʃʷaʶH] ‘honey’ /ʤɛL bʒɛH/→[ʤɛL βʒʷɛH] ‘chicken’ |

- 4.

- Again, the contrast of fricative aspiration still exists in /pC/ clusters:

| (24) | /ps/ | /psoH/ ‘to grind: 1sg’ | /pʃ/ | /pʃaʶH/ ‘honey’ |

| /psʰ/ | /psʰoH/ ‘to select: 1sg’ | /pʃʰ/ | /pʃʰaʶH/ ‘cedar’ | |

| /pʂ/ | /pʂəH/ ‘to speak: 1pl’ | |||

| /pʂʰ/ | /pʂʰəH/ ‘to go: 3 (light verb)’ |

- 5.

- Apart from prefix P- in inflected verbs, there are also nominal examples showing that the status of the bilabial C1 is stable in Rongpa phonology; see minimal pairs in (25):

| (25) | /ts/ | /tsaʁH/ ‘fat (meat)’ | /r/ | /reH/ ‘cliff’ |

| /pts/ | /ptsaʁH/ ‘rust’ | /br/ | /breH/ ‘horse’ | |

| /s/ | /siL siH/ ‘scarecrow’ | /l/ | /leH/ ‘ground; earth’ | |

| /ps/ | /psiH/ ‘moth (in wool)’ | /pl/ | /pleL/ ‘wooden plate’ | |

| /ʧ/ | /ʧəL ʧəH paʁL/ ‘cicada’ | /ʒ/ | /ʒeH/ ‘sheep’ | |

| /pʧ/ | /pʧəH pʧəL/ ‘temple (of the body)’ | /bʒ/ | /bʒeL/ ‘scabbard’ | |

| /tʂ/ | /tʂoʁL/ ‘ploughshare’ | |||

| /ptʂ/ | /ptʂoʁH/ ‘bull’ |

- 6.

- The combination of /bv/ is rather marginal since it is observed only once in our database, namely /bveH/→[βveH] ‘pig’. The transcription of ‘pig’ as /bveH/→[βveH] is also attested by the 3rd person form of /kəL veH/ ‘to shake’, that is, /kəL P-veH/→[kəL βveH] ‘he shakes’. My consultant judged the second syllable [βveH] as homophonic with /bveH/→[βveH] ‘pig’.

- 7.

- Note that except for /bv/, C2 = labial and velar consonants are almost absent in Table 9. It appears that clusters such as [pph], [pk], and [bɡ] are not allowed for the phonological restrictions in this language. This fact can also be attested by the morphological evidence of the third-person prefix P- attached to the verb root with bilabial and velar consonant initials. See examples in (26):

| (26) | /P-peH/→[peH] ‘He digs’ /P-kheL/→[kheL] ‘He airs (the clothes)’ |

| (27) | /P-kʰaʶL/→[qʰwaʶL] ‘He picks’ /P-xkaʶH/→[χqwaʶH] ‘He carves’ |

3.2.4. Clusters with Glide /w/

| (28) | /kaʶL/ ‘drop down’ | /kʰaʶL kʰaʶH/ ‘be angry’ |

| /kwaʁH loʶL/ ‘iron stove’ | /kʰwaʁL/ ‘to pick: 3’ | |

| /ɡɛL/ ‘to owe: 1pl’ | /xkɛL/ ‘to carry (on shoulder): 1pl’ | |

| /ɡwɛL/ ‘to block: 3’ | /xkwɛL/ ‘charcoal’ |

| (29) | /P-kʰaʶL/→[qʰwaʶL] ‘He picks’ /P-xkaʶH/→[xqwaʶH] ‘He carves’ |

4. Rhymes

4.1. Plain Vowels

- Minimal sets of all eight plain vowels

| (30) | /i/ /e/ /ɛ/ /ɘ/ /ɜ/ /ə/ /o/ /u/ | /ɡiH/ ‘to like:1pl’ /ɡeH/ ‘to ripe (fruit)’ /ɡɛH/ ‘saddle’ /ɡɘH/ ‘vulture’ /ɡɜH/ ‘to warm oneself (by a fire): 1sg’ /ɡəH/ ‘to warm oneself (by a fire): 1pl’ /ɡoH/ ‘supper’ /ɡuL/ ‘be freezing; to owe (money)’ |

- 2.

- Closed vowels /i/ and /u/

| (31) | /i/ | /miH/ ‘wound’ | /ɡiH/ ‘to like: 1pl’ |

| /u/ | /muH/ ‘sky’ | /ɡuL/ ‘to owe (money)’ |

- 3.

- Close-mid central vowel /ɘ/

| (32) | /ɘ/ | /xpɘH/ ‘to invert’ | /ʒeH/ ‘sheep’ |

| /e/ | /xpeH/ ‘Tibetan incense’ | /ʒɘH/ ‘to move’ | |

| /ə/ | /xpəH / ‘to soak: 1pl’ | /ʒəH/ ‘to sleep: 1pl’ |

| (33) | /pɘL/→[pwɘH] ‘cow dung’ /mɘH/→[mwɘH] ‘butter’ /xɘH/→[xwɘH] ‘mouse’ /ɡɘH/→[ɡwɘH] ‘vulture’ |

| (34) | /ɣlɘH/→[ɣlɘH] ‘hand’ /xtɘH/→[xtɘH] ‘excrement’ /xnɘH/→[xnɘH] ‘sisters (of a man)’ /tʰɘH/→[tʰɘH] ‘grain (barley and wheat)’ |

- 4.

- Close-mid front vowels /e/ and back /o/

| (35) | /i/ | /ʒiH/→[ʒɨH] ‘face’ | /ziL/→[zɨL] ‘wool’ |

| /e/ | /ʒeH/→[ʒɪH] ‘sheep’ | /zeL/→[zɪL] ‘liver’ | |

| (36) | /u/ | /kuL/→[kʉL] ‘tent’ | /xkuL/→[xkʊL] ‘to give birth (child)’ |

| /o/ | /koL/→[kʊL] ‘porcupine’ | /xkoL/→[xkʉL] ‘to carry (on shoulder)’ |

- 5.

- Central vowels /ɜ/ and /ə/

| (37) | /vɜH/ ‘tsampa’ | /xpɜH/ ‘pancreas’ |

| /vəH/ ‘belly’ | /xpəH/ ‘potherb’ | |

| /tsʰɜH/ ‘goat’ | /ʃɜH/ ‘interest’ | |

| /tsʰəH/→[tsʰz̍H] ‘wrinkle’ | /ʃəH/→[ʃʒ̍H] ‘Selaginella’ | |

| /xtʂɜH/ ‘rheum officinale’ | /xkɜH/ ‘sound’ | |

| /xtʂəH/→[xtʂɻ̍ H] ‘waist’ | /kə/ ‘orientational prefix: leftward’ |

- 6.

- Open front vowel /ɛ/

4.2. Uvularized Vowels

- A phonemic analysis

| (38) | /oʁ/ | /xpoʶH/ ‘ice’ | /tsoʶH/ ‘bridge’ |

| /əʁ/ | /xpəʶH/ ‘to blow: 1pl’ | /tsəʶH/ ‘ankle’ | |

| /eʁ/ | /xpeʶH/ ‘official; leader’ | /tseʶL tseʶH/ ‘be wet’ | |

| /ɜʶ/ | /xpɜʶH/ ‘goiter; pus’ | /tsɜʶH/ ‘deer’ | |

| /aʁ/ | /xpaʶL/ ‘toad’ | /tsaʶH/ ‘fat [N]’ |

| (39) | /o/ | /koL/ ‘porcupine’ | /ə/ | /tʂʰəH NbuH/ ‘buttocks’ |

| /oʶ/ | /koʶL/ ‘valley’ | /əʶ/ | /tʂʰəʁH NbuH/ ‘ox horn’ | |

| /e/ | /xpeH/ ‘Tibetan incense’ | /ɜ/ | /xpɜH/ ‘pancreas’ | |

| /eʶ/ | /xpeʶH/ ‘leader; official’ | /ɜʶ/ | /xpɜʁH/ ‘goiter; pus’ | |

| /ɛ/ | /kʰɛL kʰɛH/ ‘to break up (the family)’ | |||

| /aʶ/ | /kʰaʶL kʰaʶH/ ‘be angry’ |

- 2.

- Allophones of vowel /ɜʶ/

| (40) | /mɜʶL/→[mɔL] ‘fire’ /ɣɜʶL/→[ʁɔL] ‘treetop’ |

| (41) | /tsɜʶH/→[tsʌH] ‘deer’ /tʂɜʶH/→[tʂʌH] ‘to squeeze’ |

- 3.

- Uvularized open vowel /aʶ/

- 4.

- Phonological characteristics of plain and uvularized vowels

- ①

- Phonotactic constraints

- ②

- Evidence from the first element /x, ɣ/ of the complex initials

| (42) | /xpoʁH/→[χpoʁH] ‘ice’ /xʧʰəʁH/→[χʧʰəʁH] ‘dog’ /xkaʁH/→[χqaʁH] ‘to carve: 3’ |

| (43) | /xtʂɛH ɡɛH xpeL/→[xtʂɛH ɡɛH xpeL] ‘walnut tree’ /loʁH xpeL/→[loʁH χpeL] ‘tree’ |

- ③

- Evidence from vowel harmony processes

| (44) | /kə-xtəʁH/→[qəʁH-xtəʁL] ‘ort: pfv-to ask: 1pl’ /ɣə-bzəʁH/→[ʁəʁH-βzəʁL] ‘ort: pfv -to pull: 1sg’ |

4.3. Vowel Harmony

4.3.1. Uvularization Harmony

- Question marker ɛH-, non-past negative prefix mɛ-, prohibitive prefix tɛ-

| (45) | /ɛH-ʤoH/→[ɛH-ʤoH] ‘q-to run: 2sg’ /mɛ-ʤoH/→[mɛH-ʤoL] ‘neg: npst-to run: 1sg’ /tɛH-ʤoL/→[tɛH-ʤoL] ‘proh-to run: 2sg’ |

| (46) | /ɛH-xtsɜʶH/→[aʶH-χtsɜʶH] ‘q-to pound (walnut): 2sg’ /mɛ-xtsɜʶH/→[maʶH-χtsɜʶL] ‘neg: npst-to pound (walnut): 1sg’ /tɛ-xtsɜʶH/→[taʶH-χtsɜʶL] ‘proh-to pound (walnut): 2sg’ |

- 2.

- Orientation prefix22

| (47) | /tə-xtoʁH/→[təʁH-χtoʁL] ‘ort:pfv-to rob: 1sg’ /lə-kʰəʁL/→[ləʁL-qʰəʁH] ‘ort:pfv-to collect (firewood): 1pl’ /kə-xmeʁH/→[qəʁH-χmeʁL] ‘ort:pfv-to close (eyes): 2pl’ /kə-xnɜʁL/→[qəʶ-χnɜʁL] ‘ort:pfv-to light up: 1sg’ /lə-P-tʂʰaʶH/→[laʶH-ptʂʰaʶL] ‘ort:pfv-to take apart: 3’ |

| (48) | /kə-xpəʁH/→[qəʁH-χpəʁL] ‘ort: pfv-to blow: 1pl’ /ɣə-xtʂʰəʁL/→[ʁəʁL-χtʂʰəʁH] ‘ort: pfv-to untie: 1pl’ |

- 3.

- “tə- ‘one’ + classifier/quantifier” combinations

| (49) | [təH ɣuH] ‘a bundle (of wood)’ [təL tsəH] ‘a piece (of bamboo)’ [təL ʐɛH] ‘a bowl (of rice)’ |

| (50) | [təʶL xsoʶH] ‘a liǎng (in Chinese liǎng两, a unit of weight that equals to 50 g)’ [təʶL sʰɜʶH] ‘a pail (of water)’ [təʶL qʰaʶH] ‘a package (of tobacco)’ |

4.3.2. Height Harmony

| (51) | /tə-ʤɛH/→[tɛH-ʤɛL] ‘ort:pfv-to run: 1pl’ /lə-kʰɛH/→[lɛH-kʰɛL] ‘ort:pfv-to bask (under the sunshine): 1pl’ |

| (52) | /tə-zaʁH/→[taʁH-zaʁL] ‘ort:pfv-to hit: 3’ /lə-kʰwaʁL/→[laʁL-qʰwaʁH] ‘ort:pfv-to collect (firewood): 3’ |

| (53) | /kə-xtɛL/→[kəL-xtɛH] *[kɛH-xtɛL] ‘ort:pfv-to forge (iron): 1pl’ /ɣə-dzaʁL/→[ʁəʁL-dzaʁH] *[ʁaʁL-dzaʁH] ‘ort:pfv-to thread (a needle): 3’ |

4.3.3. Harmony on Roundedness

| (54) | /kə-dzoH/→[koH-dzoL]~[kəH-dzoL] ‘ort:pfv-to teach: 1sg’ /ɣə-tʰoH/→[ɣoH-tʰoL]~[ɣəH-tʰoL] ‘ort:pfv-to drink: 1sg’ |

| (55) | /ɣə-dzoʁL/→[ʁoʁL-dzoʁH]~[ʁəʁL-dzoʁH] ‘ort:pfv-to knead (needle): 1sg’ /lə-roʁL/→[loʁL-roʁH]~[ləʁL-roʁH] ‘ort:pfv-to laugh: 1sg’ |

5. Tone and Pitch Patterns

5.1. Tones in Monosyllabic Words

5.2. Pitch Patterns in Disyllabic Words

| (56) | [L-H] | [ʃiL dɘH] ‘garlic’ | [ɛL kɛH] ‘older brother’ |

| [H-L] | [ʃiH dɘL] ‘coral’ | [ɛH kɛL] ‘tick (parasite)’ | |

| (57) | [L-H] | [xkoL xliH] ‘bone marrow’ | [ʃiL mɘH] ‘sand’ |

| [H-H] | [xkoH xliH] ‘nine months’ | [ʃiH mɘH] ‘dried roasted barley’ |

| (58) | [pɜʶLH nəL] ‘others’ [tsɜLH nəL] ‘they’ (/tsɜLH/ ‘he; she’) [ɡeLH niL] ‘be early’ |

5.3. Pitch Patterns in Verb Morphology

5.3.1. Perfective and Imperative Verb Forms

| (59) | Perfective: Underlying /H/→surface [H-L] [kəH-loL] (ort: pfv-∑) ‘I have planted’ [ʁəʶH-l̥ɜʶL] (ort: pfv-∑) ‘I have herded (sheeps)’ [rəʶH-ptoʶL] (ort: pfv-∑) ‘I have twined’ [ləH-tsɜL] (ort: pfv-∑) ‘I have milked (the cow)’ [təH-sʰɜL] (ort: pfv-∑) ‘I have killed’ | |

| (60) | Perfective: Underlying /L/→surface [L-H]: [kəL-xtoH] (ort: pfv-∑) ‘I have pounded’ [ʁəʶL-χnoʶH] (or: pfv-∑) ‘I have peeled off’ [rəL-ntʰoH] (or: pfv-∑) ‘I have held (in hands)’ [ləʶL-qoʶH] (or: pfv-∑) ‘I have picked’ [təʶL-zoʶH] (or: pfv-∑) ‘I have taken away’ | |

| (61) | Imperative: Underlying /H/→surface [H-L]: [kəH-xtoL] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You pound!’ [ʁəʶH-χnoʶL] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You peel off!’ [rəH-ntʰoL] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You hold!’ [ləʶH-qoʶL] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You pick!’ [təʶH-zoʶL] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You take away!’ |

| (62) | Imperative: Underlying /L/→surface [H-H]: [kəH-loH] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You plant!’ [ɣəH-l̥ɜʶH] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You herd!’ [rəʶH-ptoʶH] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You twine!’ [ləH-tsɜH] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You milk!’ [təH-sʰɜH] (ort: imp-∑) ‘You kill!’ |

5.3.2. Negative Prefixes

| (63) | Underlying /H/→[H-L]: [mɛH-loL] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t plant’ [maʶH-l̥ɜʶL] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t herd’ [maʶH-ptoʶL] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t twine’ [mɛH-tsɜL] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t milk’ [mɛH-sʰɜL] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t kill’ |

| (64) | Underlying /L/→[L-H]: [mɛL-xtoH] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t pound’ [maʶL-χnoʶH] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t peel off’ [mɛL-ntʰoH] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t hold’ [maʶL-qoʶH] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t pick’ [maʶL-zoʶH] (neg: npst-∑) ‘I don’t take away’ |

| (65) | Both underlying /H/ and /L/→[H-H-L]: [kəH-məH-loL] (or-neg:pst-∑) ‘I haven’t planted’ [kəH-məH-sʰɜL] (or-neg:pst-∑) ‘I haven’t killed’ [ləʶH-məʶH-qoʶL] (or-neg:pst-∑) ‘I haven’t picked’ [ləʶH-məʶH-zoʶL] (or-neg:pst-∑) ‘I haven’t taken away’ |

| (66) | Underlying /H/→[H-L]: [tɛH-loL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t plant!’ [taʶH-l̥ɜʶL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t herd!’ [taʶH-ptoʶL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t twine!’ [tɛH-tsɜL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t milk!’ [tɛH-sʰɜL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t kill!’ |

| (67) | Underlying /L/→[LH-L]: [tɛLH-xtoL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t pound!’ [taʶLH-χnoʶL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t peel off!’ [tɛLH-ntʰoL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t hold!’ [taʶLH-qoʶL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t pick!’ [taʶLH-zoʶL] (proh-∑) ‘Don’t take away!’ |

6. Concluding Remarks

- Rongpa has a substantial phonemic inventory, which comprises 43 simple consonant initials, 84 consonant clusters as complex initials, 13 vowels and 2 contrastive tones. All the contrasts in this paper are proved by (near) minimal pairs/sets.

- Regarding consonant inventory, affricates and fricatives in Rongpa show a three-way contrast in their places of articulation (i.e., dental, postalveolar, and retroflex). Coronal fricatives also show three-way contrast in their manner of articulation (i.e., voiceless unaspirated, voiceless aspirated, and voiced). The contrast of fricative aspiration is still remaining even in consonant clusters.

- Rongpa exhibits a complex vocalic system. The phonemic contrast between plain vowels and uvularized vowels is attested. Uvularization is a conspicuous and indispensable vowel feature, which plays an essential role in phonotactic rules and vowel harmony process.

- As for word prosody, two contrastive tones in monosyllabic words, /H/ and /L/, are used to distinguish lexical meanings, while disyllabic words mainly exhibit four pitch patterns: [H-H], [H-L], [L-H], and [LH-L], among which [H-H] and [H-L] are not contrastive. Pitch patterns in verb constructions are also examined, and polar alternations are employed to distinguish different grammatical categories such as perfective and imperative.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

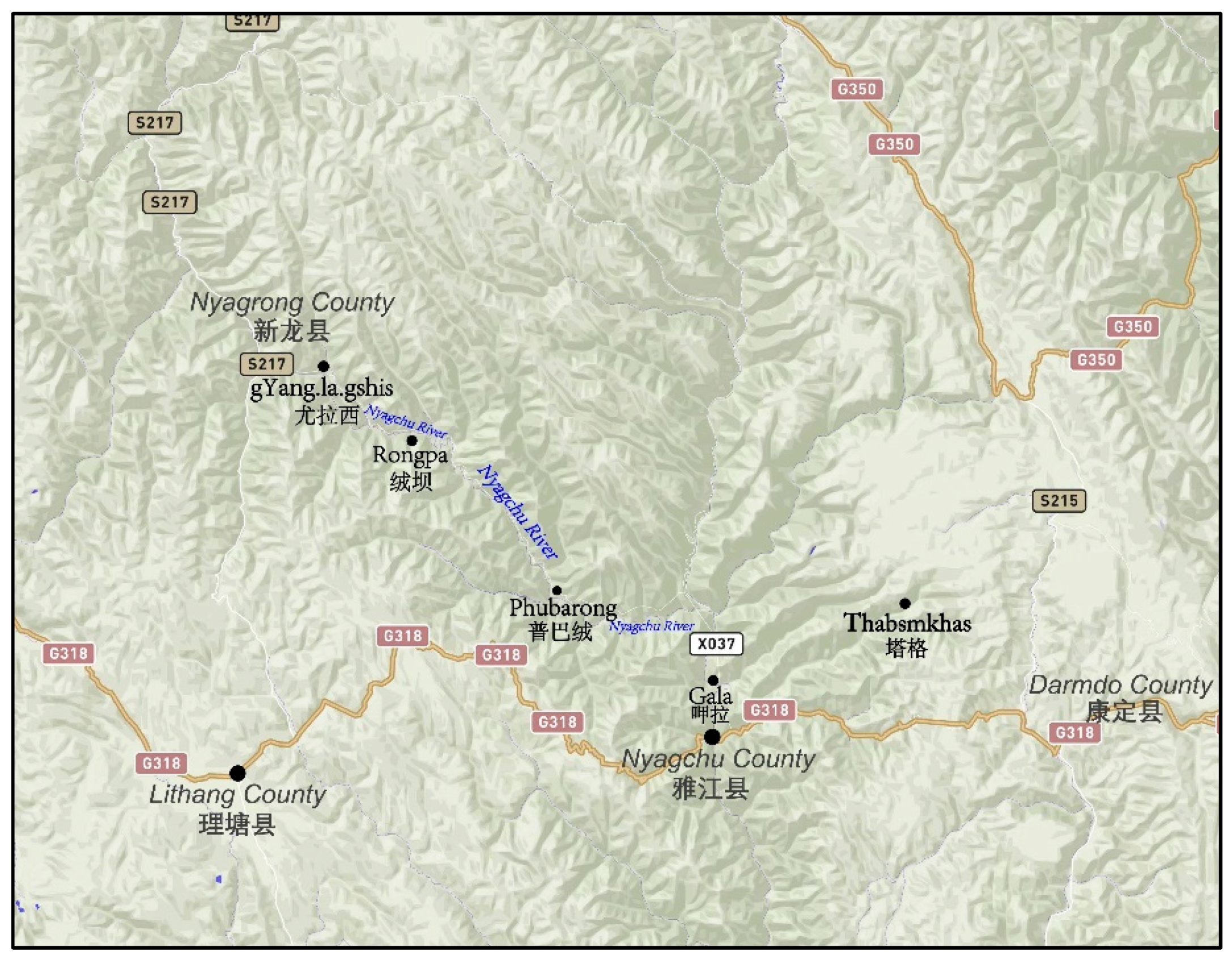

| 1 | Tuanjie Township (团结乡) has been renamed as Gara Town (ག་ར呷拉镇) since 1979 (c.f., Yǎjiāng Xiànzhì Biānzuǎn Wěiyuánhuì (雅江县志编纂委员会) 2000, p. 39). | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Wang (1991, p. 46) mentioned that: ”Speakers of Choyul in Nyagrong County refer to their language as [ʨho55 kɛ55], and the regions where [ʨho55 kɛ55] is spoken, including places belonging to Nyagchu and Lithang County, are collectively called [ʨho55 y55]. If [kɛ55] and [y55] were borrowed from Tibetan <skad> and <yul>, [ʨho55 kɛ55] and [ʨho55 y55] can be labeled as ‘què (却) language’ and ‘què (却) region’, respectively. However, the origin and meaning of ‘què (却)’ still remain ambiguous”. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | In previous literature, Choyul has been alternatively refer to “Zhaba” in various cases. Sun (1983, pp. 155–63; 2013, pp. 151–63) uses data of “Zhaba” collected by Shaozun Lu. Lu (1985) also uses the term “Zhaba (扎巴)” to refer to the Choyul variety that he studied (i.e., Tuanjie (团结) variety spoken in Nyaychu County). However, just as Huang (1991b, p. 65) points out, the language studied by Lu (1985) is actually a variety of Choyul, which is distinct from the bona fide Zhaba. Sun (2001, p. 158; 2016, p. 6) also admitted that Choyul had been mislabled as “Zhaba”, though he misuses the term “Zhaba” again in Sun (2013, pp. 151–63). | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | According to Sun (2001), the notion “Qiangic” emerged in the early 1960s, constituting only three languages: Qiang, Pumi and Rgyalrong. It was expanded since the late 1970s, when a number of seemingly related languages (including Tangut) were added to the branch. Specifically, Sun (2001, p. 160) divided the said languages into two branches, subsuming Choyul and Zhaba into the Southern branch. Meanwhile, Sun noticed that the two languages also show diagnositic characteristics of both Northern and Southern branches, so he suggested that they could be in an “intermediate genetic position”. After that, in Sun (2016, p. 4), he proposed a three-way division of “Qiangic” into: (1) the Northern branch, which comprises Rgyalrong (嘉戎), Ergong (尔龚) and Lavrung (拉坞戎); (2) the Central branch, consituting Zhaba (扎巴), Choyul (却域), Qiang (羌), Tangut (西夏), Muya (木雅) and Pumi (普米); and (3) the Southern branch, which includes Shixing (史兴), Namuyi (纳木义), Ersu (尔苏) and Guiqiong (贵琼). | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | /N/ stands for an archiphonemic nasal that is homorganic to the following consonant. See Section 3.2.2 for detailed discussion. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | In this paper, tones/pitch patterns are marked by superscripted “H” and “L” after each syllable. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Abbreviations “1sg, 1pl, 2sg, 2pl, 3” are used to indicate the person and number of the subject that the verb alters for. Otherwise, the gloss of verbs without such specifications are underlying verb forms (without any vowel alternations). Other abbreviations occur in this paper include: 1 = first person, 2 = second person, 3 = third person, imp = imperative, neg = negative, npst = non-past, ort = orientational prefix, pfv = perfective, pl = plural, proh = prohibitve, pst = past, q = question marker, sg = singular. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Note that the place of articulation of the consonants in these minimal pairs is not conditioned by the following vowel or the tone. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | This distribution can be clearly observed when the verb /niL/ ‘to tell’ undergoes vocalic alternation to conjugate for the person and number of the subject. When it comes to conjugation for a second-person-singular subject, the vowel alters to [ə] and the initial nasal is realized as [n]; while for first person singular and plural and second-person plural subjects, the vowels can trigger palatalization. Thus, the nasal initial is realized as [ɲ]. Consider the verb forms in this table:

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Probably borrowed from Tibetan སྣ <sna>. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Probably borrowed from Tibetan རྣ <rna>. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Another consultant of ours, Zhengna (正娜), who is a cousin of our language teacher, and who worked with Prof. You-Jing Lin in 2019, tends to pronounce the first elements /x/ and /ɣ/ more emphatically than our language teacher. She produces the pharyngeal sound in question with more force even when C1 is voiceless /x/. In her speech, C1 = /x/ is usually produced as a voiceless pharyngeal fricative [ħ], with a voiceless flap [ɾ̥] between C1 and C2, e.g., /ɣniH/→[ʕɾniH] ‘ear’; /xniH/→[ħɾ̥niH] ‘nose’. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Unlike in Japhug Rgyalrong (Jacques 2021, p. 48) and Thebo Tibetan (Lin 2018, p. 29), there is no solid evidence for treating the prenasalized voiced stops and affricates as single phonemes in Rongpa. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | The capitalized P- here represents an archiphonemic prefix that indexes the third-person subject. It has 5 allomorphes:

If we observe the distribution of these allomorphs, we can conclude that the prefix P- assimilates with the manner of articulation of the following simple consonant of the verb root, which can be formulated using this phonological rule:

Note that P- will not realised as a voiced bilaibial stop [b-] before verb roots with voiced stops or affricates, e.g., /P-diL/→[diL] *[bdiL] ‘He accumulates’; /P-ʤiH/→[ʤiH] *[bʤiH] ‘He runs’.

All these allomorphs of P- show its [+labial, +round] nature. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | Note that in [loŋL tʂʰəH] ‘food steamer’ and [toŋL tʂʰaʶH təL roL] ‘one thousand’, *[ŋtʂʰ] is not a legal cluster in Rongpa. Thus, [ŋ] is analysed as the coda of the preceding syllable. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | This is a unit of length which is a synonym for Chinese “一拃 (zhǎ)”. Interestingly, Rongpa further distinguishes /NdzəʁH/, which refers to the length between the thumb and forefinger, and /ptʂʰiH/, which refers to the length between thumb and the middle finger. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Note that the cluster /pl/→[ɸl] is only observed in three instances in our database, namely: /plɛL/→[ɸlɛL] ‘to plait one’s hair’ (probably borrowed from Tibetan བླས <blas>); /plɘH/→[ɸlɘH] ‘to unbraid one’s hair; to spread out’; and /pleH/→[ɸleH] ‘wooden plate’. Both /plɛL/ ‘to plait one’s hair’ and /plɘH/ ‘to unbraid one’s hair; to spread out’ undergoes the same morphological process involving vowel alternations to index the person and number of the subject like native Rongpa verbs:

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | The marginal status of “[b] + voiced stop/affricate” clusters is also justified by the fact that the third-person prefix P- is not realized as predicted [b] when it attaches to the verb roots with voiced stop or affricate initials (see footnote 14 for detaied discussion of the third-person prefix P-), e.g., /P-diL/→[diL] *[bdiL] ‘He accumulates’; /P-ʤiH/→[ʤiH] *[bʤiH] ‘He runs’; /P-dʐiH/→[dʐiH] *[bdʐiH] ‘He queues’. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | Probably borrowed from Tibetan བཙའ <btsa’> ‘rust’. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | There is only one example of /i/ after labial onset in my current lexicon: /miH/→[mɨH] ‘wound’(probably etymologically from Tibetan རྨ <rma>). | ||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | This phenomenon of assimilation can also seen as the uvularization of the whole syllable. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | The basic orientation system in Rongpa is shown in the following table in forms of prefixes:

These prefixes code both orientation and perfectivity. When prefixed with a motion verb, the orientational connotation of the prefix is explicitly specified. While in other cases, the selection of prefixes is dependent on the verb’s inherent lexical semantics or can be totally conventionalized. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | The fact that the whole syllable is uvularized was also observed in Puxi Horpa (Lin et al. 2012, p. 193) and Mawo Qiang (Sun and Evans 2013, p. 141). | ||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | Some Tibetic languages exhibits a partial tone system, in which the tones are only contrastive in restricted circumstances. In Thebo (迭部), for example, tones are only contrastive when the syllable bears sonorant or voiceless unaspirated initials (Lin 2014), while this is not the case in Rongpa. | ||||||||||||||||||

References

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2018. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer, Version 6.0.43; Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 8 September 2018).

- Chirkova, Katia. 2012. The Qiangic subgroup from an aerial perspective: A case study of language of Muli. Language and Linguistics 13: 133–70. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Chenhao, and Jackson T.-S. Sun. 2020. On pharyngealized vowels in Northern Horpa: An acoustic and ultrasound study. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 147: 2928–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, Jonathan P. 2006a. Origins of vowel pharyngealization in Hongyan Qiang. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 29: 91–123. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Jonathan P. 2006b. Vowel quality in Hongyan Qiang. Language and Linguistics 7: 731–54. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Jonathan P., Jackson T.-S. Sun, Chenhao Chiu, and Michelle Liou. 2016. Uvular approximation as an articulatory vowel feature. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 46: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Yang. 2015. Description d’une langue qianguique: Le muya. Ph.D. dissertation, EHESS, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Xun. 2018. Le rgyalrong zbu, une langue tibéto-birmane de chine du Sud-ouest: Une étude descriptive, typologique et comparative. Ph.D. thesis, Institut national des langues et des civilisations orientales, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Xun. 2020. Uvulars and uvularization in Tangut phonology. Languages and Linguistics 21: 175–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Bufan. 1991a. Mùyǎyǔ 木雅语 [The Minyag Language]. In Zàngmiǎnyǔ Shíwǔ Zhǒng 藏缅语十五种 [Fifteen Tibeto-Burman Languages]. Edited by Dai Qingxia, Huang Bufan, Fu Ailan, Renzeng Wangmu and Liu Juhuang. Beijing: Beijing Yanshan Press, pp. 98–131. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Bufan. 1991b. Zhābāyǔ 扎巴语 [The Zhaba Language]. In Zàngmiǎnyǔ Shíwǔ Zhǒng 藏缅语十五种 [Fifteen Tibeto-Burman Languages]. Edited by Dai Qingxia, Huang Bufan, Fu Ailan, Renzeng Wangmu and Liu Juhuang. Beijing: Beijing Yanshan Press, pp. 64–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, Guillaume, Yunfan Lai, Anton Antonov, and Lobsang Nima. 2017. Stau (Ergong, Horpa). In The Sino-Tibetan Languages, 2nd ed. Edited by Graham Thurgood and Randy J. LaPolla. London: Routledge, pp. 597–613. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, Guillaume. 2021. A Grammar of Japhug [Comprehensive Grammar Library 1]. Berlin: Language Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ladefoged, Peter, and Ian Maddieson. 1996. The Sounds of World’s Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Ladefoged, Peter, and Keith Johnson. 2014. A Course of Phonetics, 7th ed. Stanford: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, You-Jing, Jackson T.-S. Sun, and Zhengxian Chen. 2012. Púxī Huòěryǔ Ruǎn’èhuà de Yǔyīn Duìlì 蒲西霍尔语软腭化的语音对立 [Non-consonantal velarization in Puxi Horpa]. Yǔyánxué Lùncóng 语言学论丛 [Linguistic Studies] 45: 187–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, You-Jing. 2014. Thebo. In Phonological Profiles of Little Studied Tibetic Varieties. Edited by Jackson T.-S. Sun. Language and Linguistics Monograph Series 55. Taiwan: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, pp. 215–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, You-Jing. 2018. Chápù Jiāróngyǔ Dàzàng Fāngyán de Yīnxì fēnxī—Jiānlùn fāngyán tèshū yuányīn bǐjiào 茶堡嘉戎语大藏方言的音系分析——兼论方言特殊元音比较 [A phonological analysis of The Tatshi Dialect of Japhug Rgyalrong—With a cross-dialect comparison of special vowels]. Mínzú Yǔwén 民族语文 2018: 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Shaozun. 1985. Zhābāyǔ gàikuàng扎巴语概况 [An introduction to the Zhaba language]. Mínzú yǔwén 民族语文 2: 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, Fuminobu. 2008. チュユ語の音韻体系 [The phonological system of Chuyu]. Tyuugoku Kenkyuu 16: 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Sharon, and Rachel Walker. 2011. “Harmony system”. In The Handbook of Phonological Theory, 2nd ed. Edited by John Goldsmith; Jason Riggle and Alan C. L. Yu. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 240–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Hongkai. 1983. Liùjiāng Liúyù de mínzú yǔyán jí qí xìshǔ fēnlèi 六江流域的民族语言及其系属分类 [Minority Languages of the six river valley and their genetic classification]. Mínzú xuébào 民族学报 [Scholarly Journal of Nationalities] 3: 99–273. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Hongkai, ed. 1991. Zàngmiǎnyǔ Yǔyīn hé Cíhuì 藏缅语语音和词汇 [Tibeto-Burman Sounds and Lexicon]. Beijing: China Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Hongkai. 2001. Lùn Zàngmiǎnyǔzú Zhōng de Qiāngyǔzhīyǔyán 论藏缅语族中的羌语支语言 [On Language of the Qiangic branch in Tibeto-Burman]. Language and Linguistics 2.1: 157–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Hongkai. 2013. Bājiāng Liúyù de Zàngmiǎnyǔ 八江流域的藏缅语 [Tibeto-Burman Languages of the Eight River Valley]. Beijing: China Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Hongkai. 2016. Zàngmiǎnyǔzú Qiāngyǔzhī yánjiū 藏缅语族羌语支研究 [A Study of the Qiangic Branch of Tibeto-Burman Languages]. Beijing: China Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Jackson T.-S. 2000. Stem Alternations in Puxi Verb Inflection: Toward Validating the rGyalrongic Subgroup in Qiangic. Language and Linguistics 1: 211–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Jackson T.-S. 2004. Verb-Stem Variations in Showu rGyalrong. In Studies on Sino-Tibetan Languages: Papers in Honor of Professor Hwang-Cherng Gong on His Seventieth Birthday. Edited by Ying-Chin Lin, Fangmin Xu, Cunzhi Li, T.-S. Jackson Sun, Xiufang Yang and Dah-an Ho. Taiwan: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, pp. 269–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Jackson T.-S., and Jonathan P. Evans. 2013. Máwō Qiāngyǔ yuányīn yīnxì zàitàn 麻窝羌语元音音系再探 [The vocalic system of Mawo Qiang revisited]. In Eastward Flows the Great River—Festschrift in Honor of Professor William S-Y. Wang on His 80th Birthday. Edited by Shi Feng and Peng Gang. Kowloon: City University of Hong Kong Press, pp. 135–51. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Hiroyuki, and Sonam Wangmo. 2016. Lhagang Choyu: A first look at its sociolinguistic status. Studies in Asian Geolinguistics II: 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Hiroyuki, and Sonam Wangmo. 2018. Lhagang Choyu Wordlist with the Thamkhas Dialect of Minyag Rabgang Khams (Lhagang, Dartsendo). Asian and African Languages and Linguistics 12: 133–60. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Hiroyuki, Sonam Wangmo, and Jesse P. Gates. n.d. An Outline of the Sound Structure of Lhagang Choyu: A Newly Recognized Highly Endangered Language in Khams Minyag. Available online: https://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_48_05.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Suzuki, Hiroyuki. 2018. Lǐtángxiàn jíqí Zhōubiān Zàngzú yǔyán xiànzhuàng diàochá yǔ fēnxī 理塘县及其周边藏族语言现状调查与分析 [Current situation of Tibetans’ languages in Lithang County and its surroundings: Research and analysis]. Mínzú Xuékān 民族学刊 [Journal of Ethnology] 46: 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Van Way, John R. 2018. The Phonetics and Phonology of Nyagrong Minyag, an Endangered Language of Western China. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Hawai’i, Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Tianxi. 1991. Quèyùyǔ 却域语 [The Queyu Language]. In Zàngmiǎnyǔ Shíwǔ Zhǒng 藏缅语十五种 [Fifteen Tibeto-Burman Languages]. Edited by Dai Qingxia, Huang Bufan, Fu Ailan, Renzeng Wangmu and Liu Juhuang. Beijing: Beijing Yanshan Press, pp. 46–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yǎjiāng Xiànzhì Biānzuǎn Wěiyuánhuì (雅江县志编纂委员会). 2000. Yǎjiāng Xiànzhì 雅江县志 [Yajiang Anuals]. Chengdu: Bashu Shushe. [Google Scholar]

| First Element (C1) | Second Element (C2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a. | dorsal fricative | /x/ /ɣ/ | obstruents; voiced nasals; voiced lateral; |

| b. | nasal | /m/ /N/5 | voiceless unaspirated stops and affricates; voiced stops and affricates; voiced nasal /n/; |

| c. | bilabial stop | /p/ /b/ | all coronal consonants; labiodental fricative /v/; |

| d. | velar consonant | /k/ /kʰ/ /ɡ/ | labial glide /w/ |

| Syllable Types | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| V | /ɛH/ ‘question marker’6 | /aʶH tsaʶL/ ‘turnip’ | |

| CV | /muH/ ‘sky’ | /səL/ ‘nit’ | |

| C1C2V | C1=/x/ or /ɣ/ | /xpaʶL/ ‘toad’ | /ɣmaʁH/ ‘bamboo’ |

| C1=/m/ or /N/ | /mdʐiH/ ‘thunder’ | /NtʰeH/ ‘to sing’ | |

| C1=/p/ or /b/ | /ptʂɛL/ ‘friend’ | /bziH/ ‘marmot’ | |

| C1=/k/, /kʰ/ or /ɡ/ | /kʰwaʶL/ ‘to pick: 3’ | /ɡwɛL/ ‘to block: 3’7 | |

| C1C2C3V | /xkwɛL/ ‘charcoal’ | /xkwaʶH/ ‘to carve: 3’ | |

| Place | Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manner | ||||||||

| plosive | voiceless | −asp | p | t | k | |||

| +asp | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | |||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||||

| affricate | voiceless | −asp | ts | ʧ | tʂ | |||

| +asp | tsʰ | ʧʰ | tʂʰ | |||||

| voiced | dz | ʤ | dʐ | |||||

| nasal | voiceless | m̥ | n̥ | (ŋ̊) | ||||

| voiced | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| trill | voiceless | r̥ | ||||||

| voiced | r | |||||||

| fricative | voiceless | −asp | (f) | s | ʃ | ʂ | x | |

| +asp | sʰ | ʃʰ | ʂʰ | |||||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ʐ | ɣ | |||

| approximant | voiced | w | j | |||||

| lateral approximant | voiceless | l̥ | ||||||

| voiced | l | |||||||

| Phoneme | Example | Phoneme | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| /p/ | /pəH/ ‘sun’ | /ʧ/ | /ʧəL ʧəH paʶL/ ‘cicada’ |

| /pʰ/ | /pʰɘL/ ‘salary’ | /ʧʰ/ | /ʧʰiH/ ‘salt’ |

| /b/ | /bɛL vəH/ ‘pine tree’ | /ʤ/ | /ʤɛH/ ‘Han nationality’ |

| /m̥/ | /m̥ɜH/ ‘person’ | /ʃ/ | /ʃəH/ ‘incense’ |

| /m/ | /muH/ ‘sky’ | /ʃʰ/ | /ʃʰɘH/ ‘worship’ |

| /w/ | /wɜL rəH/ ‘bear’ | /ʒ/ | /ʒeH/ ‘house’ |

| /f/ | /paʶL feH/ ‘soda’ | /tʂ/ | /tʂoʁH/ ‘ploughshare’ |

| /v/ | /vɜH/ ‘tsampa’ | /tʂʰ/ | /tʂʰoʁH/ ‘fence’ |

| /t/ | /toʁH/ ‘wing’ | /dʐ/ | /dʐəH/ ‘to ruminate (animals)’ |

| /tʰ/ | /tʰoʁH/ ‘meat’ | /ʂ/ | /ʂəH/ ‘louse’ |

| /d/ | /doL/ ‘to fly’ | /ʂʰ/ | /ʂʰɜH/ ‘strength’ |

| /ts/ | /tsɜL/ ‘he’ | /ʐ/ | /ʐəL/ ‘water’ |

| /tsʰ/ | /tsʰɜH/ ‘goat’ | /j/ | /ɛL jɛH/ ‘sister-in-law’ |

| /dz/ | /dzeH/ ‘to teach’ | /k/ | /kuL/ ‘tent’ |

| /n̥/ | /n̥ɜL n̥ɜH/ ‘green; blue’ | /kʰ/ | /kʰuH/ ‘corner’ |

| /n/ | /nɜʶH/ ‘milk’ | /ɡ/ | /ɡoH/ ‘supper’ |

| /r̥/ | /r̥ɛL/ ‘to tear’ | /ŋ̊/ | /ŋ̊ɜʶH/ ‘gold’ |

| /r/ | /rəL/ ‘mountain; hill’ | /ŋ/ | /ŋɛH/ ‘silver’ |

| /s/ | /sɜH/ ‘pepper’ | /x/ | /xɘH/ ‘mouse’ |

| /sʰ/ | /sʰɜH/ ‘to kill’ | /ɣ/ | /ɣɘH/ ‘barley liquor’ |

| /z/ | /zeL/ ‘liver’ | ||

| /l̥/ | /l̥aʁH/ ‘wind’ | ||

| /l/ | /leH/ ‘land; ground’ |

| C2 | Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Retroflex | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plosive | voiceless | −asp | xp | xt | xk | ||

| +asp | xpʰ | xtʰ | xkʰ | ||||

| voiced | ɣd | ɣɡ | |||||

| affricate | voiceless | −asp | xts | xʧ | xtʂ | ||

| +asp | xtsʰ | xʧʰ | xtʂʰ | ||||

| voiced | ɣdz | ||||||

| nasal | voiced | xm | xn | xŋ | |||

| ɣm | ɣn | ɣŋ | |||||

| fricative | voiceless | −asp | xs | xʃ | xʂ | ||

| +asp | xsʰ | xʃʰ | xʂʰ | ||||

| voiced | ɣz | ɣʒ | ɣʐ | ||||

| lateral approximant | voiced | xl | |||||

| ɣl | |||||||

| Cluster | Example | Cluster | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| /xp/ | /xpeL/ ‘urine’ | /xʧ/ | /xʧeH/ ‘warehouse’ |

| /xpʰ/ | /xpʰoʁL/ ‘to bury’ | /xʧʰ/ | /xʧʰəʁH/ ‘dog’ |

| /xm/ | /xmɜH/ ‘crupper-strap’ | /xʃ/ | /xʃəʁL xʃəʁH/ ‘be wide’ |

| /ɣm/ | /ɣmaʁH/ ‘bamboo’ | /xʃʰ/ | /xʃʰɜʶH/ ‘to scatter (with hands)’ |

| /xt/ | /xtaʁL/ ‘wall’ | /ɣʒ/ | /ɣʒəʁL/ ‘to blend’ |

| /xtʰ/ | /xtʰɘL/ ‘to stamp’ | /xtʂ/ | /xtʂeH/ ‘cloud’ |

| /ɣd/ | /ɣdəʁH/ ‘umbrella’ | /xtʂʰ/ | /xtʂʰaʁH/ ‘sifter’ |

| /xts/ | /xtsɘL/ ‘hail’ | /xʂ/ | /xʂaʁL/ ‘soil’ |

| /xtsʰ/ | /xtsʰaʁH/ ‘cough’ | /xʂʰ/ | /xʂʰɜL/ ‘to chase (cattle)’ |

| /ɣdz/ | /ɣdzɜʶH/ ‘pillar’ | /ɣʐ/ | /ɣʐɜH/ ‘fertilizer’ |

| /xn/ | /xnaʁL/ ‘to peel’ | /xk/ | /xkɜH/ ‘sound’ |

| /ɣn/ | /ɣnɜH/ ‘tail’ | /xkʰ/ | /xkʰuH/ ‘smoke’ |

| /xs/ | /xsoʁL/ ‘pine oil’ | /ɣɡ/ | /xkuH ɣɡeH/ ‘thief’ |

| /xsʰ/ | /xsʰɜʶL xsʰɜʶH/ ‘be sharp’ | /xŋ/ | /xŋɜʶL/ ‘parrot’ |

| /ɣz/ | /ɣzəʁH/ ‘agate’ | /ɣŋ/ | /ɣŋiH/ ‘drum’ |

| /xl/ | /xlaʁH/ ‘white poplar’ | ||

| /ɣl/ | /ɣlɘH/ ‘hand’ |

| C2 | Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Retroflex | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plosive | voiceless | +asp | mtʰ | ||||

| Npʰ | Ntʰ | Nkʰ | |||||

| voiced | −asp | md | |||||

| Nb | Nd | Nɡ | |||||

| affricate | voiceless | +asp | mtsʰ | mʧʰ | mtʂʰ | ||

| Ntsʰ | Nʧʰ | Ntʂʰ | |||||

| voiced | −asp | mdz | mʤ | mdʐ | |||

| Ndz | Nʤ | Ndʐ | |||||

| nasal | voiced | mn | |||||

| Rongpa | WT | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| [ndaʶL.mbaʶH] | འདམ་པ <’dam.pa> | ‘mud’ |

| [ʃuH.ŋkʰuH] | སྤྱང་ཀི <spyang.ki> | ‘wolf’ |

| [loŋL.ŋkʰɘH] | རླུང <rlung> | ‘blower (used to chaff)’ |

| [bdʐaʶL.mbaʶH] | འགམ་པ <’gram.pa> | ‘cheek’ |

| [loŋL.tʂʰəH]15 | རླངས <rlangs> | ‘food steamer’ |

| [toŋL.tʂʰaʶH.təL.roL] | སྟོང <stong> | ‘(one) thousand’ |

| Cluster | Example | Cluster | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| /Npʰ/ | /NpʰaʶL raʶH/ ‘to scratch’ | ||

| /Nb/ | /NbeH/ ‘to protect’ | ||

| /mtʰ/ | /mtʰiL mtʰiH/ ‘be tall’ | /Ntʰ/ | /NtʰeH/ ‘to sing’ |

| /md/ | /mdiH/ ‘meal’ | /Nd/ | /NdeH/ ‘what’ |

| /mtsʰ/ | /mtsʰiH/ ‘lake’ | /Ntsʰ/ | /NtsʰoL/ ‘nest’ |

| /mdz/ | /mdzɜH/ ‘room’ | /Ndz/ | /NdzɜH/ ‘to insert’ |

| /mʧʰ/ | /mʧʰɜʶL mʧʰɜʶH/ ‘be pretty’ | /Nʧʰ/ | /tʂiL NʧʰuH/ ‘horse bell’ |

| /mʤ/ | /mʤɜH/ ‘be sticky’ | /Nʤ/ | /NʤəL/ ‘trouser’ |

| /mtʂʰ/ | /mtʂʰaʁH/ ‘plant ash’ | /Ntʂʰ/ | /NtʂʰeH/ ‘be expensive’ |

| /mdʐ/ | /mdʐiH/ ‘thunder’ | /Ndʐ/ | /NdʐeL/ ‘selvedge’ |

| /mn/ | /mnɘH/ ‘eye’ | /Nkʰ/ | /NkʰuL/ ‘to use: 3’ |

| /Nɡ/ | /NɡuH NɡuL/ ‘to nod’ |

| C2 | Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Retroflex | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plosive | voiceless | −asp | pt | |||

| +asp | ptʰ | |||||

| voiced | (bd) | |||||

| affricate | voiceless | −asp | pts | pʧ | ptʂ | |

| +asp | ptsʰ | pʧʰ | ptʂʰ | |||

| voiced | (bdz) | (bʤ) | (bdʐ) | |||

| trill | voiceless | pr̥ | ||||

| voiced | br | |||||

| fricative | voiced | −asp | ps | pʃ | pʂ | |

| +asp | psʰ | pʃʰ | pʂʰ | |||

| voiced | bv | bz | bʒ | bʐ | ||

| lateral approximant | voiceless | pl̥ | ||||

| voiced | pl | |||||

| bl | ||||||

| Cluster | Example | WT | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| [bd] | [niL xuH tsaʁL bdɘH] | བདུན <bdun> | ‘twenty-seven’ |

| [bdz] | [sʰaʁL bdzɜH muL tɘL] | (བརྩི <brdzi>)? | ‘cosmos flower’ |

| [bdʐ] | [bdʐaʁL mbaʁH] | འགྲམ་པ <’gram.pa> | ‘cheek’ |

| [bʤ] | [bʤɜH] | (རྒྱག <rgyag>)? | ‘be full’ |

| [niL xuH tsaʁL bʤeH] | བརྒྱད <brgyad> | ‘twenty-eight’ | |

| [bʤuL] | (བརྒྱངས <brgyangs>)? | ‘to extend’ |

| Cluster | Example | Cluster | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| /bv/ | /bveH/ ‘pig’ | /pʧ/ | /pʧəH pʧəL/ ‘temple (of the body)’ |

| /pt/ | /ptaʁH/ ‘to twine: 3’ | /pʧʰ/ | /pʧʰiH/ ‘to eat: 3’ |

| /ptʰ/ | /ptʰeH/ ‘to drink: 3’ | /bʤ/ | /bʤɜL/ ‘be full’ |

| /bd/ | /niL xuH tsaʁL bdɘH/ ‘twenty-seven’ | /pʃ/ | /pʃaʁH/ ‘honey’ |

| /pts/ | /ptseH/ ‘ghost’ | /pʃʰ/ | /pʃʰaʁH/ ‘cedar’ |

| /ptsʰ/ | /ptsʰɛH/ ‘to dye: 3’ | /bʒ/ | /bʒeL/ ‘sheath’ |

| /bdz/ | /sʰaʁL bdzɜH muL tɘL/ ‘cosmos flower’ | /ptʂ/ | /ptʂɛL/ ‘friend’ |

| /pr̥/ | /pr̥ɛL/ ‘to tear down: 3’ | /ptʂʰ/ | /ptʂʰəH roH/ ‘six’ |

| /br/ | /braʁH/ ‘cow’ | /bdʐ/ | /bdʐaʁL NbaʁH/ ‘cheek’ |

| /ps/ | /psiH/ ‘worm’ | /pʂ/ | /pʂəH/ ‘to speak: 3’ |

| /psʰ/ | /psʰɜH/ ‘to kill: 3’ | /pʂʰ/ | /pʂʰəH/ ‘to go (light verb): 3’ |

| /bz/ | /bziH/ ‘marmot’ | /bʐ/ | /bʐəH roL/ ‘four’ |

| /pl̥/ | /pl̥oʁH/ ‘to knead: 3’ | ||

| /pl/ | /pleH/ ‘wooden plate’ | ||

| /bl/ | /blaʁH/ ‘thigh’ |

| Cluster | Example | Cluster | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| /kw/ | /kwaʁH loʶL/ ‘iron stove’ | /xkw/ | /xkwɛH/ ‘be shy’ |

| /kʰw/ | /kʰwaʁL/ ‘to pick: 3’ | ||

| /ɡw/ | /ɡwɛL/ ‘to block: 3’ |

| Plain Vowels | i | e | ɛ | ɘ | ə | ɜ | o | u |

| Uvularized vowels | eʶ | aʁ | əʁ | ɜʶ | oʁ |

| Phoneme | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| /i/ | /ziL/ ‘wool’ | /ʧʰiH/ ‘to eat’ |

| /e/ | /leH/ ‘ground; earth’ | /tʰeH/ ‘to drink’ |

| /ɛ/ | /rɛL/ ‘cloth’ | /psʰɛH/ ‘to select (seed)’ |

| /ɘ/ | /nɘL/ ‘forest’ | /ʒɘH/ ‘to take way; to move’ |

| /ə/ | /pəH/ ‘sun’ | /ʧʰəH/ ‘to lift; to raise’ |

| /ɜ/ | /pɜH/ ‘photo’ | /tsɜH/ ‘to milk (cow)’ |

| /o/ | /koL/ ‘porcupine’ | /xkoH/ ‘to believe’ |

| /u/ | /muH/ ‘sky’ | /xkuL/ ‘to give birth (a child)’ |

| /oʶ/ | /zoʶH/ ‘woman’ | /ʐoʶL/ ‘to promise’ |

| /əʶ/ | /sʰəʶH/ ‘blood’ | /NdʐəʶL/ ‘to support (with hands)’ |

| /eʶ/ | /xpeʶH/ ‘official; leader’ | /xʃʰeʶH/ ‘to snap (with hands): 2’ |

| /ɜʶ/ | /mɜʶL/ ‘fire’ | /xnɜʶH/ ‘to shine; to light up’ |

| /aʶ/ | /ɣaʶH/ ‘door’ | /xkaʶH/ ‘to carve’ |

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Retroflex | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ɨ] | (√)20 | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| [ʉ] | √ | – | – | – | √ |

| Subject | 1sg | 1pl | 2sg | 2pl | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /tsɜH/ ‘to milk (a cow)’ | tsɜH | tsəH | tsɜH | tsɜH | ptsɜH |

| /xtsɜʶH/ ‘to pound (walnut)’ | xtsɜʶH | xtsəʶH | xtsɜʶH | xtsɜʶH | xtsɜʶH |

| Vowel Type | Plain Vowels | Uvularized Vowels | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preceding Consonant | |||

| labial | √ | √ | |

| alveolar | √ | √ | |

| Postalveolar | √ | √ | |

| retroflex | √ | √ | |

| velar | √ | – | |

| uvular | – | √ | |

| Tone | Pitch Pattern | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| /H/ | [44]~[42] | /l̥aʁH/→[l̥aʁ44] ‘wind’ | /xtʂəʁH/→[χtʂəʁ42] ‘flood’ |

| /L/ | [24] | /l̥aʁL/→[l̥aʁ24] ‘wheat sprouts’ | /xtʂəʁL/→[χtʂəʁ24] ‘willow’ |

| /H/ | /L/ |

|---|---|

| /toʁH/ ‘wing’ | /toʁL/ ‘shell’ |

| /phoH/ ‘to escape: 1sg’ | /phoL/ ‘to lose (money): 1sg’ |

| /ɡoH/ ‘supper’ | /ɡoL/ ‘back (of the body)’ |

| /xtaʁH/ ‘tiger’ | /xtaʁL/ ‘wall (made by stone)’ |

| /xtʂəʁH/ ‘flood’ | /xtʂəʁL/ ‘willow’ |

| /ʤiH/ ‘to run’ | /ʤiL/ ‘scrotum’ |

| /xuH/ ‘rain’ | /xuL/ ‘yoghurt’ |

| /sheH/ ‘mind’ | /sheL/ ‘firewood’ |

| /ɣoʁH/ ‘help [N]’ | /ɣoʁL/ ‘madman’ |

| /ɣʒəʁH/ ‘balcony’ | /ɣʒəʁL/ ‘to mix: 1pl’ |

| /l̥aʁH/ ‘wind’ | /l̥aʁL/ ‘wheat sprouts’ |

| /nɛH/ ‘owl’ | /nɛL/ ‘fish’ |

| Pitch Patterns | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| [H-H] | [xteH reH] ‘fog’ | [tʂʰəH mbuH] ‘buttocks’ |

| [H-L] | [xnɜH mbɜL] ‘mouth’ | [ɣoʶH ʧʰiL] ‘sparrow’ |

| [L-H] | [xlɜL mnɜH] ‘moon’ | [pʰəL kʰɛH] ‘stomach’ |

| [LH-L] | [tsɜLH nəL] ‘they’ | [ɡeLH niL] ‘be early’ |

| ∑ | Perfective ort: pfv-∑ | Imperative ort: imp-∑ | Non-past Negative neg: npst-∑ | Past Negative ort-neg: pst-∑ | Prohibitive proh-∑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /H/ | [H-L] | [H-H] | [H-L] | [H-H-L] | [H-L] |

| /L/ | [L-H] | [H-L] | [L-H] | [LH-L] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, J. A Phonological Study of Rongpa Choyul. Languages 2023, 8, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020133

Zheng J. A Phonological Study of Rongpa Choyul. Languages. 2023; 8(2):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020133

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Jingyao. 2023. "A Phonological Study of Rongpa Choyul" Languages 8, no. 2: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020133