Abstract

Many languages of lowland South America mark remoteness distinctions in their TAM systems. In Amahuaca (Panoan; Peru) multiple remoteness distinctions are made in the past and the future. I argue that the temporal remoteness morphemes (TRMs) of Amahuaca can be understood as indications of the remoteness of the event time relative to the utterance time in matrix environments. In dependent clauses, however, the picture is more complicated. By exploring adjunct switch-reference clauses, I show that TRMs in dependent clauses display a previously unreported ambiguity reminiscent of ambiguities found with adjunct tense. Specifically, they can relate the time of the adjunct clause event to the time of the matrix event or to the utterance time. I suggest that this ambiguity may arise from the availability of multiple interpretation sites for adjunct TRMs, with the possible interpretations being constrained by the temporal semantics of switch-reference markers themselves. This work thus contributes to the empirical understanding of how TRMs are interpreted in dependent clauses, suggesting interesting potential parallels to the interpretation of adjunct tense.

1. Introduction

The encoding of temporal meanings has received a great deal of attention in the literature on cross-linguistic semantics. It has been clearly demonstrated that not all languages make use of the same set of semantic categories to locate events in time. For example, some languages, such as Paraguayan Guaraní (Tonhauser 2011) or Hausa (Mucha 2013), have been argued to semantically lack tense altogether, while other languages, such as St’át’imcets (Matthewson 2006), have been argued to have tense semantics that are underspecified compared to English. On the other hand, some languages have been argued to make use of classes of temporal meanings that English lacks. This paper will be primarily concerned with one such category of temporal operators known as temporal remoteness morphemes (TRMs; Cable 2013; see also Bohnemeyer 2018; Klecha and Bochnak 2016), which can be thought of as providing information about the length of the interval between two times.

Remoteness distinctions are relatively common in the TAM systems of languages of South America. Mueller (2013, p. 46) finds that in a sample of 63 South American Indigenous languages, 29 of them encode remoteness distinctions. I will demonstrate in this paper that, similarly to other Panoan languages, Amahuaca, a Panoan language of Peru, makes multiple remoteness distinctions in the past and future. While remoteness distinctions are often categorized as tense distinctions, I will argue that the encoding of remoteness distinctions in Amahuaca is enacted by TRMs in Cable’s (2013) sense, that is, markers that directly encode the relationship between the time of the event and the time of utterance (see Tallman and Stout 2018 on Chácobo (Panoan; Bolivia) and Chamorro 2020 on Guajajára (Tupí-Guaraní; Brazil) for accounts of remoteness marking in other Amazonian languages that discuss similarities to the properties of TRMs as understood by Cable 2013). This paper thus adds to the literature on temporal remoteness marking, and temporal semantics more generally, by providing a description and analysis of an additional language that makes use of TRMs.

In addition to the question of what categories of temporal operators languages make use of, another question that has received significant attention in the literature on temporal semantics is the behavior of temporal operators, especially tense, in dependent clauses. It is well known at this point that the encoding of temporal meanings is not identical in matrix and dependent clauses, with phenomena such as Sequence of Tense (Abusch 1997; Dowty 1982; Enç 1987, among many, many others) providing a prime example of this. In this paper, I explore how Amahuaca’s TRMs are used within adjunct switch-reference clauses to express temporal relationships between events across clauses. I demonstrate that switch-reference markers themselves encode information about the temporal sequencing between the events of two clauses. These switch-reference markers can then be combined with TRMs. It has been reported by Sparing-Chávez (1998, 2012) that when Amahuaca’s TRMs are used in this way, they indicate the duration of the time lapse between the events of the two clauses. I confirm that this use of TRMs in switch-reference clauses is possible. However, I also demonstrate that an additional reading of TRMs in switch-reference clauses is available. Under the right conditions, TRMs can also serve to indicate the length of the interval between the event of the adjunct clause and the time of utterance, giving rise to a previously unreported ambiguity in the meaning of some switch-reference constructions containing TRMs.

I connect the availability of multiple meanings for TRMs in switch-reference clauses to the variation found in the expression of tense in adjunct clauses cross-linguistically (Arregui and Kusumoto 1998; Kubota et al. 2012; Ogihara 1994, 1996; Sharvit 2013; von Stechow and Grønn 2013, among others). I argue that, just as adjunct tense can be evaluated relative to the utterance time or some matrix time, so too can adjunct TRMs. While I do not provide a compositional analysis of TRMs in adjunct clauses, I suggest, following recent work by Newman (2021) on ambiguity in adjunct tense, that a difference in the syntactic position in which adjunct TRMs are evaluated may give rise to the two distinct readings of TRMs in switch-reference clauses. This parallel between the behavior of adjunct tenses and adjunct TRMs is predicted to be possible if TRMs, similarly to tenses, are sensitive to an evaluation time, which may not be equal to the utterance time in dependent clauses. By shining a light on the variable interpretation of TRMs in adjunct clauses, this paper thus contributes to the cross-linguistic picture of the relationship between various types of temporal operators across clauses, suggesting that similar interactions can be found with TRMs as have been observed for tense.

The structure of the paper is as follows. In Section 2 I provide background information about the morphosyntax of Amahuaca, with a special focus on the structure of adjunct switch-reference clauses. In Section 3, I discuss how temporal relationships between clauses are encoded by switch-reference markers themselves, introducing three primary paradigms of switch-reference markers that differ in the temporal sequencing they indicate between the events of two clauses. In Section 4 I introduce the TRMs of Amahuaca, first providing background on the tense and aspect system of the language and then exploring how TRMs contribute to temporal meanings in matrix environments. In Section 5 I discuss how TRMs are used in switch-reference clauses. Here I introduce the ambiguity that can arise when TRMs appear in adjunct clauses. I argue that TRMs in Amahuaca should be analyzed as instances of the same temporal category of the Gĩkũyũ TRMs discussed by Cable (2013) in Section 6 and suggest a possible avenue for understanding the ambiguity in their interpretation in adjunct clauses. Finally, I offer concluding remarks in Section 7.

2. The Morphosyntax of Switch-Reference in Amahuaca

Amahuaca is a language of the Panoan family spoken in the Peruvian and Brazilian Amazon by approximately 500 speakers (Eberhard et al. 2023). According to Fleck’s (2013) classification, it belongs to the Headwaters subgroup of the Nawa group within Mainline Panoan. The data for this paper are drawn from my fieldwork with 15 speakers of the language from 2015 through 2022. These speakers all live in the district of Sepahua, Atalaya Province, Ucayali, Peru and they ranged in age from approximately 24 to 85 years old at the time of data collection. The majority of the key data presented here on temporal meanings were collected in July 2022 with four speakers.

Amahuaca is mostly head-final in the TP domain, with the exception of AspP, which is head-initial (Clem 2022). In dependent clauses, which will be discussed further below, CP is also head-final. In matrix clauses, however, CP is head-initial, with matrix C surfacing as a second position clitic after the first syntactic constituent, as illustrated in (1)–(3) for initial phrases of various categories and the clitic =mun.1

| 1. | Initial DP | ||

| [Xano=n | hino]=mun | jiri=hi=ki=nu. | |

| woman=gen | dog=C | eat=ipfv=3.prS=decl | |

| ‘The woman’s dog is eating.’ | |||

| 2. | Initial PP | ||||

| [Nihi | muran]=mun | joni=n | jiriti | vuna=xo=nu. | |

| forest | inside=C | man=erg | food | look.for=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘The man looked for food in the woods.’ | |||||

| 3. | Initial CP | |||||

| [Hino | koshi | ka=kun]=mun | Juannu=n | Maria | yohi=xo=nu. | |

| dog | quickly | go=ds=C | Juan.lg=erg | Maria | say=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘Juan told Maria that the dog had run.’ | ||||||

The base SOV word order of the language is often obscured by pro-drop as well as scrambling, which is possible for both arguments and adjuncts. Scrambling often targets the initial Spec,CP position before the second position clitic, with a preference for constituents that bear narrow focus to appear in this position (Clem 2019b).

Amahuaca displays a tripartite system of case marking for core arguments. The ergative (=n) and nominative (=x) cases are marked overtly on transitive and intransitive subjects, respectively. The accusative case is unmarked. Both transitive and intransitive subjects may also appear in an unmarked form under the right conditions, due to differential subject marking (Clem 2019b).

Similarly to many languages of the Panoan family, Amahuaca makes extensive use of switch-reference, a strategy for morphologically indicating whether the arguments of two clauses are or are not co-referential.2 A simple same- vs. different- subject contrast is illustrated in (4) and (5).

| 4. | Marked clause subject co-referential with reference clause transitive subject | ||||

| [Jaa=xi |  | xano=ni | xuki | jova=xo=nu | |

| 3sg=nom | sing=sa.sq=C | woman=erg | corn | cook=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘After shei sang, the womani cooked corn.’ | |||||

| 5. | No argument co-reference (different subject) | ||||

| [Jonii |  | xano=nj | xuki | jova=xo=nu | |

| man | sing=ds.sq=C | woman=erg | corn | cook=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘After the mani sang, the womanj cooked corn.’ | |||||

I follow Munro (1979) and Haiman and Munro (1983) in using the term ‘marked clause’ to refer to the clause that hosts the switch-reference marker and the term ‘reference clause’ to refer to the other clause that contains the argument in the relevant (non-)co-reference relationship. In (4), the subject of the marked clause (the bracketed adjunct clause) and the reference clause (the matrix clause) are co-referential. This leads to the use of the same-subject switch-reference marker =xon (boxed) on the marked clause verb. In contrast, in (5), no arguments of the two clauses are co-referential, leading to the use of the different-subject switch-reference marker =kun. This marker can be analyzed as a type of morphological default that appears when there is no argument co-reference or when the particular co-reference relationship between arguments lacks a dedicated marker (Clem 2023; see Baker and Camargo Souza 2020 for a similar treatment of the different-subject marker in Shipibo and Yawanawa).

It has been noted for Amahuaca (Sparing-Chávez 1998, 2012), as well as for other Panoan languages (e.g., Kakataibo, Zariquiey 2018; Matses, Fleck 2003; Shipibo-Konibo, Valenzuela 2003; Yaminawa, Neely 2019; Yawanawa, Baker and Camargo Souza 2020), that the switch-reference system is incredibly rich, marking more than a simple same- vs. different-subject contrast. One feature that distinguishes the switch-reference system of Amahuaca and other Panoan languages is sensitivity to transitivity. The switch-reference markers of Amahuaca show different forms depending on whether the subject of the reference clause is a transitive agent (A) or the subject of an intransitive (S), as illustrated by comparing (4) to (6).

| 6. | Marked clause subject co-referential with reference clause intransitive subject | |||

| [Jaa=xi |  | xanoi | chirin=xo=nu | |

| 3sg=nom | sing=ss.sq=C | woman | dance=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘After shei sang, the womani danced.’ | ||||

In (4), the reference clause subject is a transitive subject, triggering the =xon form of same-subject marking, while in (6) the reference clause subject is an intransitive subject, triggering the =hax form of same-subject marking. I argue in Clem (2019c, 2023) that this sensitivity to the grammatical function of the subject can be formalized as a sensitivity of the switch-reference markers to abstract Case.

Another notable feature of the Amahuaca switch-reference system is that it shows sensitivity to the reference of the objects in both the reference clause and marked clause (Clem 2019c). This can be seen in (7) for the reference clause object and (8) for the marked clause object.

| 7. | Marked clause subject co-referential with reference clause object | ||||

| [Jaa=xi |  | hinan | xanoi | chivan-vo=xo=nu | |

| 3sg=nom | sing=so.sq=C | dog.erg | woman | chase-am=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘After shei sang, the dog chased the womani.’ | |||||

| 8. | Marked clause object co-referential with reference clause intransitive subject | ||||

| [Joni=n | xanoi |  | xanoi | ka=xo=nu | |

| man=erg | woman | find=os.sq=C | woman | go=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘After the man found the womani, the womani went.’ | |||||

In (7), the marked clause subject is co-referential with the reference clause direct object and this results in the use of the switch-reference marker =xo. In (8) the object of the marked clause is co-referential with the reference clause intransitive subject, leading to the use of the switch-reference marker =ha.

Another dimension of meaning that the switch-reference markers of Amahuaca encode is the temporal relationship between the event of the marked clause and the reference clause. All of the switch-reference markers introduced so far are part of the sequential action paradigm, which indicates that the event of the marked clause precedes the event of the reference clause (motivating the translation of these clauses with the temporal connective after). There is another paradigm that indicates simultaneous action, and yet another paradigm that indicates subsequent action or purpose. The temporal meanings of switch-reference markers will be exemplified and discussed further in Section 3.

With this understanding of the information encoded by switch-reference markers, we turn now to a discussion of the syntax of switch-reference clauses. What follows draws largely on the analysis of switch-reference in Amahuaca that I give in Clem (2023), and additional details of the analysis as well as further supporting arguments can be found there. Switch-reference marked clauses allow for all arguments of the verb to appear overtly, including overtly ergative-marked subjects, as shown in (9).3

| 9. | [Xano=ni | chopa |  | proi | hatza | jova=hi=ki=nu |

| woman=erg | clothes | wash=sa.sq=C | manioc | cook=ipfv=3.prs=decl | ||

| ‘After the womani washed clothes, shei is cooking manioc.’ | ||||||

Since overt ergative case in Amahuaca requires agreement with T (Clem 2019b), the availability of ergative subjects in marked clauses suggests that marked clauses contain at least a TP layer.

Marked clauses also allow for scrambling within them. Of particular note is that the verb in a marked clause can move to the beginning of the clause, as in (10).

| 10. | ‘After the womani boiled the meat, shei ate it.’ | |||||

| a. | [Xano=ni | nami |  | proi | ha=xo=nu | |

| woman=erg | meat | boil=sa.sq=C | do.tr=3.pst=decl | |||

| b. | [Kovin | xano=ni |  | proi | ha=xo=nu | |

| boil | woman=erg | meat=sa.sq=C | do.tr=3.pst=decl | |||

Verb fronting in matrix environments can only target Spec,CP. Assuming that the same position is targeted by verb fronting in dependent switch-reference clauses, this suggests that marked clauses also contain a CP layer. Following much of the literature on switch-reference (e.g., Arregi and Hanink 2022; Baker and Camargo Souza 2020; Watanabe 2000) I adopt the view that Amahuaca switch-reference markers are instances of C (Clem 2023). In dependent clauses, such as switch-reference clauses, C is head-final. Because of this, switch-reference C surfaces as an enclitic switch-reference marker on the linearly rightmost element within the marked clause.

In terms of the external syntax of switch-reference marked clauses, they are adjuncts that adjoin relatively high in the reference clause. Here, I will focus on instances where the reference clause is a matrix clause since the structure of matrix clauses allows for a more transparent identification of the adjunction site of the marked clause. Marked clauses generally appear in peripheral positions in the matrix clause and cannot appear to the right of aspect marking and before tense, as shown in (11).

| 11. | ‘After shei sang, the womani is washing manioc.’ | |||||||

| a. | [proi |  | xano=ni | hatza | choka=hi=ki=nu | |||

| sing=sa.sq=C | woman=erg | manioc | wash=ipfv=3.prs=decl | |||||

| b. | Xano=ni=mun hatza | choka=hi=ki=nu | [proi |  | ||||

| woman=erg=C manioc | wash=ipfv=3.prs=decl | sing=sa.sq | ||||||

| c. | Xano=ni=mun [proi |  | hatza | choka=hi=ki=nu | ||||

| woman=erg=C | sing=sa.sq | manioc | wash=ipfv=3.prs=decl | |||||

| d. | *Xano=ni=mun hatza | choka=hi | [proi |  | ||||

| woman=erg=C manioc | wash=ipfv | sing=sa.sq=3.prs=decl | ||||||

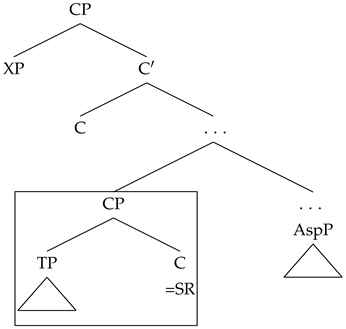

As shown in (11a) and (11b), it is possible for a marked clause to surface in left or right peripheral positions within the matrix clause. The example in (11c) shows that it is also possible for a marked clause to appear below the second position clitic. However, (11d) shows that the marked clause cannot appear between the matrix aspect and tense markers. This position is where vP-internal material surfaces (Clem 2019b, 2022). The inability of marked clauses to appear in this position suggests that their adjunction site is outside of vP.4 Evidence from the lack of Condition C effects between marked and reference clause arguments also supports a high adjunction site above the highest A-position of the reference clause arguments (Clem 2023). I will therefore assume that switch-reference marked clauses are adjoined at least as high as AspP but below C.5 The structure I will adopt for switch-reference constructions is given in (12).

| 12. |  |

Here, the switch-reference marked clause is boxed. It is a full CP with the switch-reference enclitic itself lexicalizing C. This CP is adjoined to the reference clause between AspP and C. With this understanding of the syntax of switch-reference clauses, we now turn to the question of how temporal relationships are encoded by switch-reference markers.

3. Simultaneity, Sequentiality, and Purpose in Switch-Reference

As mentioned in the previous section, switch-reference markers in Amahuaca encode a number of different pieces of information aside from simple co-reference of arguments. The focus of this section will be demonstrating the types of temporal relationships between clauses that are encoded by the switch-reference markers. Sparing-Chávez (1998, 2012) makes three basic distinctions in the types of temporal relationships expressed by switch-reference markers: sequential, non-sequential, and subsequent. I will adopt the terms sequential, simultaneous, and subsequent to refer to these three paradigms, respectively. To confirm the nature of the temporal relationships encoded by switch-reference markers, I used felicity judgments in context (Matthewson 2004). Throughout, examples are presented with the context the sentence was accepted in that makes clear the nature of the temporal relationship between the events of the marked and reference clause.

3.1. Sequential Action

The sequential action switch-reference paradigm is used when the event of the marked clause precedes the event of the reference clause. The full paradigm of sequential action switch-reference markers is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequential action switch-reference markers.

It can be seen in the above paradigm that there are multiple forms that correspond to different co-reference relationships. As in Clem (2019a, 2023), I analyze the so-called “different subject” markers as default markers that are used when none of the available co-reference markers can be used. These default markers can therefore appear in constructions where there is co-reference between arguments if the type of co-reference relationship does not correspond to one of the co-reference markers (for example, in the case of the objects of the two clauses being co-referential).

Same-subject and different-subject examples from the sequential action paradigm are given in (13) and (14).

| 13. | Context: Yesterday, Maria sang and then one hour later she cared for the children. | ||||

| [proi |  | Maria=ni | vaku-vo | chitu=shin=xo=nu | |

| sing=sa.sq=C | Maria=erg | child-pl | care.for=yest=3.pst=decl | ||

| ‘After shei sang, Mariai cared for the children.’ | |||||

| 14. | Context: Yesterday, Maria sang and then one hour later the children danced. | |||

| [Maria |  | vaku-vo | chirin=shin=xo=nu | |

| Maria | sing=ds.sq=C | child-pl | dance=yest=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘After Maria sang, the children danced.’ | ||||

In both (13) and (14), the provided context makes it clear that one hour elapsed between the marked clause event and reference clause event. The amount of time that is judged to be an acceptable lapse is not consistent across the entire sequential paradigm for all verbs. Same- and different-subject markers pattern slightly differently from one another, and additionally the lexical aspect of the predicate appears to play a role. With very short lapses of time between the marked clause and reference clause events, different-subject sequential markers are generally accepted, while same-subject sequential markers are often rejected. For example, if the contexts in (13) and (14) are modified slightly so that only one minute elapsed between the two events, the sentence in (14) remains acceptable, while the sentence in (13) is rejected. I propose that the unacceptability of the same-subject marker here is because of competition with another switch-reference marker that encodes that two events occur in rapid succession.

There is a switch-reference marker =tan in Amahuaca that does not appear to be in opposition to any other markers that encode an equivalent temporal relationship. The marker =tan, which I will refer to as the only member of the immediately sequential paradigm, encodes that two events occur in sequence with very little time passing between them. This is illustrated in (15).

| 15. | Context: Yesterday, Maria sang and then one minute later she cared for the children. | |||||

| [proi |  | / |  | Maria=ni | vaku-vo | |

| sing{=sa.imm.sq | / | =sa.sq}=C | Maria=erg | child-pl | ||

| chitu=shin=xo=nu | ||||||

| care.for=yest=3.pst=decl | ||||||

| ‘After shei sang, Mariai cared for the children.’ | ||||||

Here, the context indicates that only one minute has elapsed between the event of the marked clause and the event of the reference clause. The marker =tan can be used to indicate subject co-reference in such contexts. Unlike what can be seen with the other switch-reference paradigms in Amahuaca, there is no distinction between same-subject marking when the reference clause subject is a transitive subject vs. an intransitive subject; =tan is used in both cases. In addition, different from the other paradigms is that there is no different-subject counterpart to =tan; =tan can only be used for same-subject contexts, but there is no equivalent different-subject marker that marks immediately sequential events.

I propose that the lack of a different-subject counterpart to =tan is what drives the split in acceptability between sequential same-subject and different-subject markers in contexts involving a relatively short time lapse between events of the marked and reference clauses. Events that are separated by only a short lapse are acceptable with =tan when the subjects of the two clauses are co-referential. Because this form encodes this more specific temporal relationship, it is used instead of the more general sequential action same-subject markers =xon and =hax. However, in the case of disjoint reference of subjects, there is no more specific immediately sequential marker to compete with the general sequential different-subject marker =kun, so this marker is accepted in contexts with relatively short time lapses between events.

There also appears to be some slight variation in the acceptability of the sequential action paradigm depending on the choice of the predicates in the two clauses. With durative predicates, such as the activities vua ‘sing’, chirin ‘dance’, and chitu ‘care for’ in (13)–(15), short lapses, such as one minute, between events disfavor the use of the sequential action paradigm and result in the use of the immediately sequential marker =tan instead. However, with punctual predicates, such as semelfactives, such short lapses often allow either the sequential action marker or =tan, as seen in (16).

| 16. | Context: Yesterday, Maria sneezed and then one minute later she knocked on the door. | ||||||

| [proi |  | / |  | Maria=ni | vuva | tonton=shin=xo=nu | |

| sneeze{=sa.sq | / | sa.imm.sq}=C | Maria=erg | door | knock=yest=3.pst=decl | ||

| ‘After shei sneezed, Mariai knocked on the door.’ | |||||||

In (16), the same-subject sequential action marker =xon and the immediately sequential marker =tan are both accepted with the predicates jahoshin ‘sneeze’ and tonton ‘knock’ with a one minute lapse between the two events. This differs from what was seen in (15), where only the immediately sequential marker was accepted when the two predicates involved were durative. Thus, it appears that the lexical aspect of the predicate may also affect the acceptability of the sequential action paradigm with short time lapses between events.

3.2. Simultaneous Action

The next paradigm of switch-reference markers that I will discuss is the simultaneous action paradigm, shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Simultaneous action switch-reference markers.

Same-subject and different-subject examples from the simultaneous action paradigm are given in (17) and (18).

| 17. | Context: Yesterday, Maria sang and at the same time she cared for the children. | ||||

| [proi |  | Maria=ni | vaku-vo | chitu=shin=xo=nu | |

| sing=sa.sim=C | Maria=erg | child-pl | care.for=yest=3.pst=decl | ||

| ‘While shei sang, Mariai cared for the children.’ | |||||

| 18. | Context: Yesterday, Maria sang and at the same time the children danced. | |||

| [Maria |  | vaku-vo | chirin=shin=xo=nu | |

| Maria | sing=ds.sim=C | child-pl | dance=yest=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘While Maria sang, the children danced.’ | ||||

In (17) and (18) the provided contexts make it clear that the two events were ongoing at the same time. In both of these cases, markers from the simultaneous action paradigm are judged to be acceptable while markers from the sequential action paradigm are rejected.

The availability of the immediately sequential same-subject marker =tan once again appears to affect the acceptability of the simultaneous action markers. For different-subject contexts, the simultaneous action marker is sometimes accepted as an alternative to the sequential action marker when there is a very short lapse between events. This is shown in (19).

| 19. | Context: Yesterday, Maria sneezed and then one minute later a man coughed. | |||||

| [Maria |  | / |  | joni | hoko=shin=xo=nu | |

| Maria | sneeze{=ds.sim | / | =ds.sq}=C | man | cough=yest=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘After Maria sneezed, the man coughed.’ | ||||||

Here, the context makes it clear that one minute elapsed between the time that Maria sneezed and the man coughed. While the sequential action marker =kun is accepted in this context, so is the simultaneous action marker =kain.6 A speaker comment offered in this context indicated that one minute was not much time, therefore =kain seemed acceptable. In contrast, the simultaneous action same-subject markers are generally rejected in contexts where the events are separated by a lapse of this length, with the immediately sequential marker =tan used instead. This suggests that, once again, because there is no different-subject counterpart to =tan, there is more flexibility in using one of the more general markers, with the use of the simultaneous marker highlighting the proximity of the two events.

3.3. Subsequent Action and Purpose

The final paradigm of switch-reference markers that I will discuss is the subsequent action paradigm, shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Subsequent action switch-reference markers.

Examples of same-subject and different-subject markers for this paradigm are given in (20) and (21).

| 20. | Context: Yesterday, Maria sneezed and then one minute later she knocked on the door. | ||||

| [proi | Vuva |  | Mariai | jahoshin=shin=xo=nu | |

| door | knock=ss.sub=C | Maria | sneeze=yest=3.pst=decl | ||

| ‘Before shei knocked on the door, Mariai sneezed.’ | |||||

| 21. | Context: Yesterday, Maria sneezed and then one minute later a man coughed. | |||

| [Joni |  | Maria | jahoshin=shin=xo=nu | |

| man | cough=ds.sub=C | Maria | sneeze=yest=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘Before the man coughed, Maria sneezed.’ | ||||

In both of the given contexts, one minute elapses between the events of the marked clause and reference clause. What differs from previous examples is that the way that the sequence of events is reported places the event that occurred first in the reference clause, triggering the use of the subsequent paradigm in the marked clause. This contrast can be clearly seen by comparing (19) with (21). Here, the context is identical. The only thing that differs is which predicate appears in which clause, leading to a different switch-reference marker to indicate the correct temporal sequencing.

The subsequent paradigm is widely used to express purpose clauses, with the predicate of the marked clause indicating the purpose or desired outcome of the reference clause event. This use of the same switch-reference paradigm for subsequent action and purpose is reported by Sparing-Chávez (1998, pp. 462–63; 2012, pp. 19–21) for Amahuaca and is a feature of many Panoan switch-reference systems (see, e.g., Fleck 2003, pp. 1110–17 for Matses, Valenzuela 2003, p. 417 for Shipibo-Konibo, and Zariquiey 2018, pp. 431, 433, 442–43 for Kakataibo). In Amahuaca, this purpose use of the subsequent action paradigm is possible even when the event of the marked clause is never actually realized. This can be seen in (22).

| 22. | [[proi | Hatza |  | proi | vi=xon]=mun | huni | maro=yama=ku=nu |

| manioc | sell=sa.sub | take=sa.sq=C | 1sg | sell=neg=1.pst=decl | |||

| ‘I harvested manioc to sell, but I didn’t sell any.’ | |||||||

In (22), the clause marked with =xankin receives a purpose reading; the reason the manioc was harvested was so that it could be sold. However, the matrix clause states that none was actually sold. Thus, =xankin cannot be seen as indicating temporal sequencing in this example since the marked clause event is never realized. Instead, a purely purpose reading is available.

With this understanding of the temporal sequencing function of switch-reference clauses, I now turn to a discussion of a series of TRMs that can co-occur with switch-reference markers. I will first discuss the structure and meaning associated with these morphemes in matrix environments and will then turn to an examination of how these morphemes interact with the switch-reference system.

4. Temporal Remoteness Morphemes in Matrix Clauses

To explore the contribution of TRMs in matrix clauses, it is first necessary to provide an overview of the marking of tense and aspect in matrix clauses. Tense and aspect are marked by two separate sets of clitics in matrix environments. These clitics cannot appear in dependent clauses. Matrix aspect clitics generally appear as enclitics on the verb, however, they may cliticize to other hosts if the verb is fronted to the clause-initial position. Aspect clitics precede any material that remains internal to the vP, such as in situ subjects (Clem 2019b). This distribution suggests that aspect is a head-initial projection (Clem 2022). When there is no overt aspect clitic, sentences receive a perfective interpretation. The paradigm of aspect clitics is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Matrix aspect markers.

Examples that illustrate an aspectual distinction are given in (23) and (24).

| 23. | Kuntii=mun | choka=hi | xano=ki=nu. |

| pot=C | wash=ipfv | woman=3.prs=decl | |

| ‘The woman is washing a pot.’ | |||

| 24. | Kuntii=mun | choka=nox | xano=ki=nu. |

| pot=C | wash=hab | woman=3.prs=decl | |

| ‘The woman washes pots.’ | |||

In (23) the imperfective aspect marker =hi appears on the verb, leading to the interpretation of an ongoing event in conjunction with present tense. In (24), the habitual aspect marker =nox appears, leading to an interpretation where washing pots is something that the woman regularly does but is not necessarily ongoing at the utterance time.

In addition to the system of aspect clitics, Amahuaca also makes use of a set of tense clitics. Tense clitics surface in a clause-final clitic cluster just before the final clause-typing particle, indicating that T is a head-final projection that is higher than aspect (Clem 2022). Matrix tense clitics show a sensitivity to the person of the subject and display a simple past vs. present distinction. The tense paradigm is given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Matrix tense markers.

The contrast between present and past can be seen by comparing the examples in (25)–(27).

| 25. | Jaa=x=mun | pakuu=hi | jan=ki=nu. |

| 3sg=nom=C | fall=ipfv | 3sg=3.prs=decl | |

| ‘She/He is falling.’ | |||

| 26. | Jaa=x=mun | jan | pakuu=ki=nu. |

| 3sg=nom=C | 3sg | fall=3.prs=decl | |

| ‘She/He fell.’ (just now) | |||

| 27. | Jaa=x=mun | jan | pakuu=xo=nu. |

| 3sg=nom=C | 3sg | fall=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘She/He fell.’ (earlier) | |||

In (25), the combination of the present tense clitic =ki and the imperfective aspect clitic =hi yields a straightforward present tense meaning, as was also seen in (23). With perfective aspect, which is morphologically unmarked, the use of the present tense yields an interpretation of a very recent past. This past interpretation resulting from the combination of present tense with perfective aspect corresponds to the ‘retrospective strategy’ of present perfective resolution discussed by De Wit (2017). The example in (26) can be contrasted with (27) where the past tense marker is used and a less recent past interpretation arises. The sensitivity of tense markers to the person of the subject can be seen be comparing (27) to (28).

| 28. | Hiya=x=mun | hun | pakuu=ku=nu |

| 1sg=nom=C | 1sg | fall=1.pst=decl | |

| ‘I fell.’ | |||

In (27), the subject is third person and the form of the past tense marker is =xo. In (28), the subject is first person and the past tense marker takes the form =ku.

In addition to tense and aspect markers, which are obligatory with verbal predicates, Amahuaca displays a series of TRMs, which may optionally appear as enclitics in the verbal complex.8 These TRMs specify more precisely when the event occurred relative to the utterance time. The paradigm of TRMs is given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Temporal remoteness morphemes.

The degrees of temporal remoteness listed in Table 6 are an approximation based on discussions with and examples from multiple speakers. However, it should be noted that there is some degree of interspeaker variability in the exact intervals that are accepted for each marker. An illustration of some of the TRMs is given in (29) and (30).

| 29. | Maria=n=mun | vaku-vo | chitu=shin=xo=nu |

| Maria=erg=C | child-pl | care.for=yest=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘Maria cared for the children (yesterday).’ | |||

| 30. | Maria=n=mun | vaku-vo | chitu=yan=xo=nu |

| Maria=erg=C | child-pl | care.for=rec=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘Maria cared for the children (a few months ago).’ | |||

In (29) the marker =shin appears on the verb. Sentences with =shin are often translated with ‘yesterday’. However, most speakers accept =shin for events that have transpired within a few days of the utterance time and for at least some speakers =shin can even be used to describe events that have occurred within a few weeks of the utterance time. This can be contrasted with the example in (30) where the enclitic =yan appears instead of =shin. This yields an interpretation of the event occurring sometime within a few months of the utterance time. Speakers seem to generally agree that an event that took place at least one month and up to six months before the utterance time can be described using =yan. However, at least one speaker I consulted accepts even more distant past events marked with =yan, and this appears to be connected to a potentially marginal status of the distant past marker =tai in this speaker’s grammar.

As seen in Table 6, some of the TRMs indicate a degree of temporal remoteness in the past and others indicate a degree of temporal remoteness in the future. The markers =shin, =yan, =tai, and =ni are associated with degrees of remoteness in the past. All of these markers except =tai co-occur with the past tense clitics. When =tai occurs, the past tense clitic does not surface, as seen in (31).

| 31. | Maria=n=mun | vaku-vo | chitu=tai=nu |

| Maria=erg=C | child-pl | care.for=dist=decl | |

| ‘Maria cared for the children (a year ago).’ | |||

The lack of past tense marker in matrix clauses with =tai does not seem to be due to the fact that =tai itself is part of the tense paradigm. Recall that matrix tense markers do not appear in dependent clauses. Despite this, the TRM =ti, which seems to correspond to the matrix form =tai, can appear in dependent clauses, filling the same temporal paradigm slot as matrix =tai. Thus it seems more fitting to analyze =tai as being a morphophonologically irregular form resulting when the TRM =ti and matrix past tense clitic are adjacent.

The TRMs =nontu and =jahin indicate a degree of temporal remoteness in the future. They co-occur with matrix present tense and prospective aspect marking (the combination of which is used to locate events in the future), as illustrated in (32) and (33).10

| 32. | Maria=mun | vua=nontu=katzi=ki=nu |

| Maria=C | sing=tom=prosp=3.prs=decl | |

| ‘Maria will sing (tomorrow).’ | ||

| 33. | Maria=mun | vua=jahin=katzi=ki=nu |

| Maria=C | sing=dist.fut=prosp=3.prs=decl | |

| ‘Maria will sing (in a few years).’ | ||

In (32), the TRM =nontu appears, indicating that Maria’s singing will happen roughly tomorrow (potentially up to a few days from now). In (33), the TRM =jahin indicates that the singing will take place in a few years. There does not appear to be any TRM for the future that indicates a degree of remoteness between a few days from utterance time and a few years from utterance time. When asked about events in this interval, speakers simply use prospective aspect with no TRM.

TRMs are in complementary distribution with one another. Despite this complementarity, TRMs do not form a unified class in terms of their syntactic position. This can be diagnosed by examining the position of these markers relative to other enclitics that can appear in the verb complex. All of the TRMs appear outside negation but inside tense. This is illustrated for some of the clitics in (34) and (35).

| 34. | Maria=mun | vua=yama=shin=xo=nu |

| Maria=C | sing=neg=yest=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘Maria didn’t sing (yesterday).’ | ||

| 35. | Maria=mun | vua=yama=ni=xo=nu |

| Maria=C | sing=neg=rem=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘Maria didn’t sing (for years).’ | ||

In (29) we see the TRM =shin, and it appears between the negative clitic =yama and the past tense clitic =xo. Similarly, in (35), the TRM =ni also appears between negation and past tense.

Because the TRMs used with future appear with overt prospective aspect marking, we can also diagnose that those markers appear inside of aspect. This is illustrated in (36).

| 36. | Maria=mun | vua=yama=nontu=katzi=ki=nu |

| Maria=C | sing=neg=tom=prosp=3.prs=decl | |

| ‘‘Maria will not sing (tomorrow).’ | ||

As in (34) and (35), we can see that the TRM =nontu appears outside of negation but inside of tense. This example also illustrates that this marker occurs inside of the prospective aspect marker =katzi.

The position of the past TRMs with respect to aspect cannot be directly diagnosed since they only occur with perfective aspect, which is morphologically null. However, we can see that the past TRMs occupy at least two different positions by considering their position with respect to the third person plural subject clitic =kan that also always surfaces between negation and tense. As seen in (37) and (38), some TRMs precede the subject clitic, while others follow it.

| 37. | Jato=x=mun | chirin=shin=kan=xo=nu |

| 3pl=nom=C | dance=yest=3pl=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘They danced (yesterday).’ | ||

| 38. | Jato=x=mun | chirin=kan=ni=xo=nu |

| 3pl=nom=C | dance=3pl=rem=3.pst=decl | |

| ‘They danced (years ago).’ | ||

In (37), the clitic =shin precedes the subject clitic =kan. The TRM =yan also appears in this position. In (38), the clitic =ni follows the subject clitic =kan, immediately preceding the past tense marker =xo. The distant past TRM =tai also appears in the position after the subject clitic =kan.

The different positions of the TRMs suggests that they are not all instantiations of a single functional head in the clausal spine. Rather, the pattern of complementary distribution exhibited by these markers must arise by some other means. I suggest that their complementarity is due to the fact that their semantics are incompatible. Each of these markers indicates that the event time falls within a certain interval that is a specified distance from the utterance time, either in the past or the future. Because the intervals associated with these markers are not compatible with one another, it is not possible for more than one of them to appear.

If the complementary distribution of these markers is the result of semantics and is not due to the syntax of these markers, they need not correspond to a single functional projection in the spine. I therefore will assume for concreteness that these markers occupy adjoined positions between Neg and T. However, nothing crucial hinges on the assumption that these markers are adjoined rather than instantiating (at least) two different head positions in the spine.

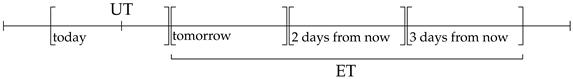

5. Temporal Remoteness Morphemes in Switch-Reference Clauses

Unlike matrix tense and aspect markers, TRMs can appear in dependent clauses. Within switch-reference clauses, the TRMs appear to the left of the switch-reference marker, as expected if switch-reference markers instantiate C and TRMs adjoin below T. This is illustrated for the TRMs =shin and =nontu in (39) and (40).

| 39. | [proi |  | Maria=ni | vaku-vo | hitu=xo=nu |

| sing=yest=sa.sq=C | Maria=erg | child-pl | care.for=3.pst=decl | ||

| ‘After shei sang (yesterday), Mariai cared for the children (today)’. | |||||

| 40. | [proi |  | vaku-vo | chitu=hi | Mariai=ki=nu |

| sing=tom=sa.sub=C | child-pl | care.for=ipfv | Maria=3.prs=decl | ||

| ‘Before shei sings (tomorrow), Mariai is caring for the children’. | |||||

In (39), the TRM =shin appears immediately before the sequential action switch-refere-nce marker =xon. As discussed earlier, =xon indicates that the marked clause event precedes the reference clause event. With the addition of =shin in the marked clause, the resulting interpretation is that the marked clause event occurred at least one and up to a few days before the reference clause event. In (40), the TRM =nontu occurs before the subsequent action switch-reference marker =jankin,11 which indicates that the marked clause event will follow the reference clause event. With =nontu in the marked clause, the resulting interpretation is that the marked clause event will occur at least one day after the reference clause event (and possibly up to a few days later).

The TRMs that indicate degrees of remoteness in the past in matrix clauses co-occur with the sequential action switch-reference markers, as seen for the TRM =shin in (39). That is, they can be used when the marked clause event precedes the reference clause event. They do not occur with subsequent action switch-reference markers. The TRMs that indicate degrees of remoteness in the future in matrix clauses co-occur with the subsequent action switch-reference markers, as shown for the TRM =nontu in (40). That is, they can be used when the marked clause event follows the reference clause event. They do not occur with sequential switch-reference markers. Further, both types of TRMs are rejected with the simultaneous action switch-reference markers, as shown for the TRM =shin in (41).12

| 41. | *[proi |  | Maria=ni | vaku-vo | chitu(=shin)=xo=nu |

| sing=yest=sa.sim=C | Maria=erg | child-pl | care.for=yest=3.pst=decl | ||

| Intended: ‘While shei sang (yesterday), Mariai cared for the children (yesterday)’. | |||||

When a TRM appears in a switch-reference clause, the same TRM can appear in the matrix clause, as shown in (42), but it is also possible for a different TRM to appear in the matrix clause, as in (43).

| 42. | [proi |  | Maria=ni | vaku-vo | chitu=shin=xo=nu |

| sing=yest=sa.sq=C | Maria=erg | child-pl | care.for=yest=3.pst=decl | ||

| ‘After shei sang, Mariai cared for the children’. | |||||

| 43. | [proi |  | Maria=ni | vaku-vo | chitu=ni=xo=nu |

| sing=yest=sa.sq=C | Maria=erg | child-pl | care.for=rem=3.pst=decl | ||

| ‘After shei sang, Mariai cared for the children’. | |||||

In (42) the TRM =shin appears in both the marked switch-reference clause and in the matrix clause. In (43), however, the TRM =shin still appears in the marked clause, but the TRM in the matrix clause is now the remote past =ni.

Given that TRMs in switch-reference clauses do not simply match the TRM of the matrix clause, this raises the question of what their semantic contribution is. Sparing-Chávez’s description of TRMs in switch-reference clauses notes that they function to “express degrees of time lapses between the events of the marked and controlling verbs” (1998, p. 454; 2012, p. 13).13 This reading of TRMs is supported by data I have collected, as seen in (44).

| 44. | Context: A few months ago, Juan caught fish and the next day he sold them. | ||||

| [proi | Yoma |  | Juannu=ni | maro=yan=xo=nu | |

| fish.species | net.fish=yest=sa.sq=C | Juan.lg=erg | sell=rec=3.pst=decl | ||

| ‘After hei caught fish, (the next day) Juani sold them.’ | |||||

In (44), the context indicates that both the events of the marked and reference clause happened a few months prior to the utterance time. This triggers the use of the TRM =yan in the matrix clause. However, =yan is not used in the marked clause here. Instead, the TRM =shin occurs in the marked clause. This is because, as made clear by the context, the event of the marked clause (catching fish) precedes the event of the reference clause by one day. Therefore, we can see here that the TRM =shin is indicating the amount of time that elapsed between the event of the marked clause and the event of the reference clause, rather than indicating the degree of remoteness of the marked clause event relative to the utterance time. If =shin was interpreted relative to the utterance time here, as it is in matrix clauses, that would mean that the event of the marked clause occurred just a day or two before the utterance time. Since this would then locate the marked clause event after the reference clause event, this would be incompatible with the semantics of the sequential action switch-reference marker =xon. The example in (44) thus aligns with Sparing-Chávez’s (1998, 2012) characterization of the function of TRMs in switch-reference clauses in Amahuaca.

While the available data support Sparing-Chávez’s (1998, 2012) claim that TRMs indicate the time lapse between the marked clause event and the reference clause event, this is not the only meaning that is possible for TRMs in switch-reference clauses. Recall that in matrix clauses, TRMs indicate the degree of temporal remoteness of the event relative to the utterance time. If TRMs functioned the same way in dependent clauses, we might expect that a TRM in a marked switch-reference clause could indicate the degree of temporal remoteness of the marked clause event relative to the utterance time, rather than relative to the reference clause event time. While this meaning has not been discussed in the literature on Amahuaca, I demonstrate that it is another available meaning for TRMs in dependent switch-reference clauses. The fact that both meanings are possible for TRMs in marked clauses results in ambiguities in some contexts. This can be seen by examining the example in (45) below.

| 45. | Context A: In a few years Maria will care for the children, and the day before that she willsing. | ||||

| Context B: Yesterday Maria sang, and in a few years she will care for the children. | |||||

| [proi |  | vaku-vo | chitu=jahin=katzi | Mariai=ki=nu | |

| sing=yest=sa.sq=C | child-pl | care.for=dist.fut=prosp | Maria=3.prs=decl | ||

| ‘Having sung, Maria will care for the children.’ | |||||

The sentence in (45) is judged to be felicitous in both of the given contexts. Both of the contexts make it clear that Maria will care for the children a few years in the future. This results in the use of the TRM =jahin in the matrix clause. Where the two contexts differ is in when the event of the marked clause (the singing) takes place. In context A, the singing will also take place in a few years but will happen one day before Maria cares for the children. In this context, the use of the TRM =shin in the marked clause serves to indicate the length of the time lapse between the events of the two clauses. This is the meaning previously observed for TRMs in dependent clauses. However, context B draws out a different meaning. Here, the context makes it clear that the event of the marked clause has already transpired the day before the utterance time. Since the reference clause event will not take place for years, this means that the amount of time that will elapse between the events of the two clauses is significantly more than the maximal lapse associated with the marker =shin. Thus, in this context, the TRM is instead indicating the temporal remoteness of the marked clause event relative to the utterance time.

To summarize, TRMs can appear in switch-reference marked clauses. When they do, there are two possible interpretations of the TRM – one relative to the time of the matrix event and one relative to the time of utterance. With this understanding of the empirical picture, I now turn to an analysis of Amahuaca TRMs.

6. Toward an Analysis of Amahuaca TRMs

In this section I provide a discussion of how the properties of TRMs in Amahuaca could be integrated into a formal account of the meanings of various types of temporal operators. While a full compositional semantic analysis of these TRMs falls outside of the scope of the current work, I suggest a promising direction that could be pursued to account for their different behavior in matrix vs. dependent clause environments.

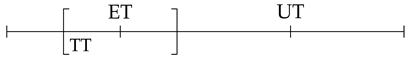

I will assume following much of the literature on temporal semantics going back to work by Reichenbach (1947) and Klein (1994) that there are three times that are relevant to the interpretation of a clause: the utterance time (UT), the event time (ET), and the topic time (TT; the time that the sentence is ‘about’). Following Klein (1994), I assume that tense serves to relate TT to UT while aspect relates ET to TT. Under this type of framework, the function of the Amahuaca past tense markers =xo and =ku is to indicate that UT follows TT while the present tense markers =ki and =ka indicate that UT is contained within TT. Amahuaca’s aspect markers then relate ET to TT. For example, the null perfective can be taken to locate ET within TT while the prospective locates ET after TT. To illustrate these assumptions, consider the examples in (46) and (47).

| 46. | Hiya=x=mun | hun | pakuu=ku=nu |

| 1sg=nom=C | 1sg | fall=1.pst=decl | |

| ‘I fell.’ | |||

| 47. | Hiya=x=mun | pakuu=katzi | hun=ka=nu |

| 1sg=nom=C | fall=prosp | 1sg=1.prs=decl | |

| ‘I am going to fall.’ | |||

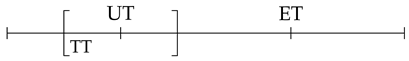

In (46), the past tense marker =ku occurs and there is no overt aspect marker, meaning that the sentence is in perfective aspect. The contribution of past tense is to locate TT before UT, as shown in (48). Meanwhile, the contribution of perfective aspect is to locate ET within TT, as seen in (49). The resulting relationship between ET, TT, and UT for the combination of past and perfective is schematized in (50).

| 48. | =ku/=xo (pst): TT < UT |

| 49. | Ø(pfv): ET ⊆ TT |

| 50. | Schematization of past perfective |

|

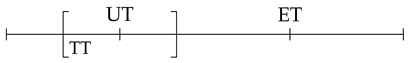

The resulting meaning will be one where the event of falling occurred and was completed before the time the sentence was uttered. We can contrast this with the interpretation of (47) where we see present tense and prospective aspect. The contribution of present tense is to locate UT within TT, as in (51), while the contribution of prospective aspect is to locate ET after TT, as in (52). The resulting relationship between the three times specified by the present prospective combination is schematized in (53).

| 51. | =ka/=ki (prs): UT ⊆ TT |

| 52. | =katzi (prosp): TT < ET |

| 53. | Schematization of present prospective |

|

As seen in (53), the result of the combination of present tense and prospective aspect is a meaning where the falling occurs after UT, that is, in the future.

With this understanding of the semantic contribution of tense and aspect, we now must consider what role TRMs play. I will first consider the matrix uses of TRMs before turning to their use in switch-reference clauses. Cable (2013) offers an analysis of TRMs in Gĩkũyũ, a Northeastern Bantu language spoken in Kenya. Gĩkũyũ has been described as having a graded tense system with various grades of past and future tense indicating events at various temporal distances from the time of speaking. Cable argues that the supposed graded tense prefixes of Gĩkũyũ are not true tense markers. That is, they do not semantically relate TT to UT. Rather, he argues that these prefixes are TRMs that function to relate ET to UT directly. As in Amahuaca, Gĩkũyũ TRMs co-occur with tense and aspect marking and Cable makes the same assumptions I do here about how tense and aspect relate UT, TT, and ET. For Cable, a crucial argument for the fact that TRMs relate ET to UT rather than TT to UT (as true tenses would) comes from future contexts.14 Cable assumes that Gĩkũyũ future is a type of aspect that locates ET after TT, as I have assumed for Amahuaca prospective aspect, and he assumes that the tense value for future sentences in Gĩkũyũ is present. Thus, a future sentence in Gĩkũyũ, similarly to a prospective sentence in Amahuaca, indicates that UT is contained within TT and that ET follows TT, as schematized in (54) below (note that this schematization is identical to the one provided for Amahuaca present prospective in (53)).

| 54. | Schematization of Gĩkũyũ future |

|

Cable (2013) argues that the Gĩkũyũ TRM kũ- ‘current future’ (or ‘current past’), which is used for events that will occur the same day as the utterance, indicates that ET overlaps with the day surrounding UT. This could be schematized as in (55) below.

| 55. | Schematization of Gĩkũyũ‘current’ TRM |

|

The prediction that this treatment of Gĩkũyũ TRMs correctly makes is that sentences such as (56) should only be felicitous if the event denoted by the predicate occurs on the same day as the utterance, as reflected by the accompanying judgment.

| 56. | Gĩkũyũ current future (Cable 2013, p. 265) | |

| Mwangi | nĩekũina | |

| Mwangi | nĩ-a-kũ-Ø-in-a | |

| Mwangi | asrt-3sgS-cur-fut-dance-fv | |

| ‘Mwangi will dance.’ | ||

| Judgment: If someone says this and Mwangi does not dance by the end of the day, then the person has made a false prediction. | ||

If the TRM kũ- was instead a tense marker, relating TT to UT, the wrong predictions arise. If the ‘current’ morpheme kũ- instead indicated that TT overlapped with the day surrounding UT, then a sentence such as (56) would be true so long as the event took place sometime after TT, including after the day of the utterance. This is because the future locates ET after TT. This interpretation is not available as the accompanying speaker judgment indicates, thus supporting the claim that TRMs are not tenses but rather relate ET to UT.

The Amahuaca data appear to be compatible with the same basic treatment as Gĩkũyũ TRMs.15 That is, they appear to also relate ET to UT (in matrix clauses). A general schema for past TRMs in matrix clauses is given in (57) and a schema for future TRMs in matrix clauses is given in (58), where ∞ means ‘overlaps’ following Cable (2013).

| 57. | Past TRMs (matrix use): ET ∞ interval before UT |

| 58. | Future TRMs (matrix use): ET ∞ interval after UT |

All of the past TRMs have in common the fact that in matrix clauses they locate ET as overlapping some interval before UT, while all of the future TRMs have in common the fact that they locate ET as overlapping some interval after UT. The different members of the TRM paradigms simply differ in the temporal distance from UT where the relevant interval is located.

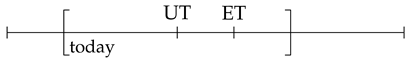

We can replicate the same kind of situation that was just discussed for Gĩkũyũ with a sentence with prospective aspect in Amahuaca, such as the one in (59).

| 59. | Maria=mun | vua=nontu=katzi=ki=nu |

| Maria=C | sing=tom=prosp=3.prs=decl | |

| ‘Maria will sing (tomorrow).’ | ||

If we assume the semantics for Amahuaca present tense in (51) and the semantics for prospective aspect in (52) we can understand =nontu as indicating that the ET overlaps an interval of (roughly) one to three days ahead of the day of the utterance, as in (60) and schematized in (61).16

| 60. | =nontu (tom; matrix use): ET ∞ interval 1–3 days after UT |

| 61. | Schematization of Amahuaca =nontu TRM |

|

This would lead to the desired meaning for (59), which is that the event will take place tomorrow or perhaps as much as two to three days in the future. As seen with Gĩkũyũ, if =nontu related TT to UT and stated that TT overlapped an interval of one to three days ahead of the day of utterance, then sentences such as (59) would be incorrectly predicted to be felicitous for any event occurring at least one day after UT. Thus, it appears that, similarly to Gĩkũyũ TRMs, Amahuaca TRMs relate ET to UT.

In his analysis of Gĩkũyũ TRMs, Cable (2013) only considers matrix uses of these markers. Thus, the semantics he gives for TRMs locates ET with respect to the evaluation time. This can be seen in the denotation he provides for the ‘current’ morpheme in (62).

| 62. | Gĩkũyũ current TRM denotation (Cable 2013, p. 253) |

| ⟦ CUR ⟧g,t = [ λe : T(e) ∞ day surrounding t . e ] |

As can be seen in (62), the ‘current’ TRM locates the time of the event as overlapping with the day surrounding the evaluation time t. In matrix clauses, the evaluation time will be equivalent to UT, resulting in the TRMs locating ET with respect to UT. However, if the evaluation time were to be non-identical to the utterance time, then the TRM could, in principle, relate ET to some other time equivalent to the evaluation time.17

In Amahuaca matrix environments, TRMs seem to always locate ET with respect to UT. Thus, in matrix contexts, they appear to align with the profile of Gĩkũyũ TRMs. In switch-reference clauses, however, we have seen an ambiguity in the meaning of Amahuaca TRMs. Recall that, informally, TRMs in switch-reference clauses can either indicate the amount of time that has elapsed or will elapse between the marked clause event and reference clause event or can express the degree of temporal remoteness of the marked clause event with respect to the time of utterance.

This ambiguity is reminiscent of, though not entirely identical to, the type of ambiguities found in the interpretation of tense in temporal adjunct clauses. It has been observed that there is cross-linguistic variation in what tense values are possible in different types of temporal adjunct clauses (Arregui and Kusumoto 1998; Kubota et al. 2012; Mucha 2015; Ogihara 1994, 1996; Sharvit 2013; von Stechow and Grønn 2013, among others). Accounts of this variation in the interpretation of tense in temporal adjunct clauses differ in whether they assume that adjunct tense is interpreted with respect to UT or relative to some other time introduced in the matrix clause. Newman (2021) offers evidence from English temporal adjunct clauses that in some cases adjunct tense is interpreted relative to UT while in other cases adjunct tense is interpreted relative to a matrix temporal operator, such as tense or aspect. Under Newman’s analysis, the evaluation time for the material within the adjunct clause, including adjunct tense, can be bound by higher operators. Thus, if adjunct tense is syntactically within the scope of matrix tense or aspect, it is interpreted relative to matrix tense or aspect, but if it is syntactically above matrix tense and aspect, its evaluation time will be equivalent to UT. To derive the correct interpretation for temporal connectives and adjunct tense, Newman argues that material within temporal adjunct clauses (specifically the complement of the temporal connective) can QR to a position above the adjunction position of the adjunct clause to be interpreted outside the scope of operators that c-command the adjunct clause. This can result in adjunct tense receiving an interpretation relative to UT if it QRs high enough in the matrix clause.

While Newman’s work, and much of the other work on the temporal interpretation of adjunct clauses, focuses on tense, this type of analysis provides a promising potential avenue for analyzing the ambiguous interpretation of TRMs in Amahuaca switch-reference clauses. If the structural position that the TRM is interpreted in can result in its evaluation time either being sensitive or insensitive to reference clause temporal operators, this could yield the attested interpretations.18 If we assume that switch-reference marked clauses can adjoin within the scope of the reference clause temporal operators, the evaluation time for material within the marked clause will not be equivalent to UT but instead will be sensitive to those reference clause operators. If the TRM is interpreted in its position within the marked clause, it will locate the marked clause predicate ET relative to the evaluation time which in this case will be bound by a reference clause temporal operator. This will result in the reading of TRMs that is relative to the reference clause time, that is, the reading that indicates the amount of time that has elapsed between the events of the two clauses. If, instead, a constituent containing the TRM QRs to a position outside the scope of higher temporal operators, its evaluation time will be equivalent to UT. This will yield a reading of the temporal connective that is identical to the matrix reading, where it locates ET relative to UT.19

If we assume that TRMs in marked switch-reference clauses in Amahuaca have at least two possible interpretation sites, this can provide insight into the ambiguity of sentences such as (45), repeated as (63) below for ease of exposition.

| 63. | Context A: In a few years Maria will care for the children, and the day before that she willsing. | ||||

| Context B: Yesterday Maria sang, and in a few years she will care for the children. | |||||

| [proi |  | vaku-vo | chitu=jahin=katzi | Mariai=ki=nu | |

| sing=yest=sa.sq=C | child-pl | care.for=dist.fut=prosp | Maria=3.prs=decl | ||

| ‘Having sung, Maria will care for the children.’ | |||||

The reading picked out by context A would represent an interpretation of the TRM in its position within the marked clause, within the scope of matrix temporal operators. The reading picked out by context B, on the other hand, would represent a case of the TRM QRing above matrix temporal operators to allow its evaluation time to be equivalent to UT.20

Finally, if we consider the semantic contribution of switch-reference markers, we can understand why sentences such as (44), repeated as (64), are not similarly ambiguous.

| 64. | Context: A few months ago, Juan caught fish and the next day he sold them. | ||||

| [proi | Yoma |  | Juannu=ni | maro=yan=xo=nu | |

| fish.species | net.fish=yest=sa.sq=C | Juan.lg=erg | sell=rec=3.pst=decl | ||

| ‘After hei caught fish, (the next day) Juani sold them.’ | |||||

In (44), only the reading corresponding to a low interpretation of the TRM within the marked clause is available. If the TRM QRed to a position above the matrix temporal operators, it would locate the marked clause ET within an interval roughly one to three days before UT. However, this would then create a contradiction since the sequential action switch-reference marker =xon indicates that the marked clause event precedes the reference clause event. Because the matrix ET is located roughly one to six months before UT because of the TRM =yan, an event only one to three days before UT cannot precede the matrix event. Thus, the higher interpretation site of the TRM will not yield an internally consistent interpretation of the sentence.

We have seen in this section, then, that an analysis of TRMs that treats them as relating ET to UT can account for their behavior in matrix clauses. To allow for the ambiguity seen in adjunct switch-reference clauses, we can assume that the evaluation time for TRMs is dependent on the position in which the TRM is interpreted. While I leave the details of a compositional semantic analysis of Amahuaca temporal operators and the ambiguity that arises in adjunct clauses to future work, this analogy to adjunct tense ambiguities provides a promising direction and the basic idea that TRMs may be able to be interpreted in multiple positions, resulting in ambiguities, aligns with work on TRMs in other types of dependent clauses (Cable 2014).

7. Conclusions

I have shown in this paper that Amahuaca displays a system of TRMs that encode multiple remoteness distinctions in the past and future. In matrix clauses these TRMs behave as we would expect based on the analysis of TRMs given by Cable (2013). We can understand their semantic contribution as locating ET relative to UT.

When the behavior of TRMs in switch-reference clauses is examined, a more complex picture emerges. We have seen that one of the functions of switch-reference marking in Amahuaca is to indicate the temporal sequencing of events across clauses, with three main types of temporal relationships being encoded by switch-reference markers. When TRMs combine with switch-reference markers, a previously unreported ambiguity arises, depending on whether the TRM is evaluated relative to a matrix time or to UT.

Compared to the behavior of tense in adjunct clauses (and dependent clauses more generally), the behavior of TRMs in dependent clauses is relatively unexplored cross-linguistically. Cable (2014) notes that TRMs in complements of verbs of speech are generally evaluated relative to matrix UT but can be evaluated relative to the UT of the reported speech with matrix future marking. Klecha and Bochnak (2016) report that Luganda TRMs are evaluated with respect to UT in complement clauses. Thus, the Amahuaca data broaden the cross-linguistic picture of the possible interpretations of TRMs in dependent clauses. In Amahuaca adjunct clauses, the reading of TRMs relative to matrix time is the more unrestricted reading, with the reading relative to UT being constrained by the semantic contribution of switch-reference markers. This raises an interesting question as to how much variation there is cross-linguistically in the interpretation of TRMs across various types of dependent clauses as well as to what degree this cross-linguistic variation mirrors patterns of variation found with better-explored temporal operators such as tense.

Funding

Portions of this work were made possible by Oswalt Endangered Language Grants.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Berkeley (protocol: 2015-04-7446, approved: 04/27/15, 03/29/16) and the University of California, San Diego (protocol: 803757, approved: 05/12/22).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all Amahuaca speakers who collaborated in this research.

Data Availability Statement

Relevant data are contained in this article. Additional data are available from the author upon request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all of my Amahuaca collaborators, and especially the four speakers who contributed the majority of the key data on temporal meanings in 2022: José Piño Bonangué, Celia Soria Pérez, Rolando Soria Pérez, and one speaker who wishes to remain anonymous. I also thank Virginia Dawson, Line Mikkelsen, Scott AnderBois, and the members of UC San Diego’s Syntax & Semantics Babble for helpful discussion. Finally, I am grateful to the editors of this special issue, Maria Luisa Zubizarreta and Guillaume Thomas, as well as the anonymous reviewers who provided feedback. All errors are mine alone.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1 | First person |

| 2 | Second person |

| 3 | Third person |

| AM | Associated motion |

| ASRT | Assertive |

| C | Complementizer |

| CUR | Current TRM |

| DECL | Declarative |

| DIST | Distant TRM |

| DS | Different subject |

| ERG | Ergative case |

| ET | Event time |

| FUT | Future |

| FV | Final vowel |

| GEN | Genitive case |

| HAB | Habitual aspect |

| IMM | Immediate |

| IPFV | Imperfective aspect |

| LG | Long form |

| LOC | Locative case |

| NEG | Negation |

| NOM | Nominative case |

| OS | Marked clause object co-referential with reference clause intransitive subject |

| PFV | Perfective aspect |

| PL | Plural |

| PROSP | Prospective aspect |

| PRS | Present tense |

| PST | Past tense |

| RC | Relative clause morphology |

| REC | Recent past TRM |

| REM | Remote past TRM |

| S | Subject |

| SA | Marked clause subject co-referential with reference clause transitive subject |

| SG | Singular |

| SIM | Simultaneous |

| SO | Marked clause subject co-referential with reference clause object |

| SQ | Sequential |

| SS | Marked clause subject co-referential with reference clause intransitive subject |

| SUB | Subsequent |

| TOM | “Tomorrow” future TRM |

| TR | Transitive |

| TRM | Temporal remoteness morpheme |

| TT | Topic time |

| UT | Utterance time |

| YEST | “Yesterday” past TRM |

Notes

| 1 | As I discuss in Clem (2019b, 2022), evidence for treating =mun as a head in the C domain comes not only from second position effects but also from its sensitivity to clause type as it appears only in matrix declarative clauses and disappears in embedded and interrogative clauses. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Amahuaca’s switch-reference system only tracks argument (non-)co-reference. There is no evidence that broader notions such as discourse or topic (dis)continuity can affect the choice of switch-reference markers as is often the case in systems that allow so-called ‘non-canonical’ switch-reference. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | The ergative subject in (9) can be diagnosed as being internal to the marked clause rather than being to the left of the marked clause within the matrix clause due to its position with the rest of the marked clause before the second position clitic. As this position can only be occupied by one constituent, the ergative nominal must form a constituent with the rest of the marked clause. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | The unacceptability of marked clauses in the position between aspect and tense contrasts with the behavior of nominalized internally headed relative clauses that are merged in argument positions in the vP. These nominalized clauses can appear between matrix aspect and tense markers, as shown in (65).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | In Clem (2023), I treat switch-reference marked clauses as TP adjuncts. As will be discussed later, the temporal interpretations of some switch-reference clauses suggest that they may have an adjunction site below some matrix temporal operators. I therefore remain open to the possibility of other adjunction sites besides TP here. I note in Clem (2023, p. 67) that an adjunction site lower than TP is still compatible with the syntactic account of switch-reference argued for there and with the lack of Condition C effects shown there since subjects do not obligatorily move out of the vP in Amahuaca and since scrambling in Amahuaca shows properties of A-movement (Clem 2019a, pp. 25–33). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | The alternation between =hain and =kain is phonologically-conditioned allomorphy and is predictable based on the prosodic form of the verb root. This alternation occurs for other switch-reference markers that have an initial glottal stop as well. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Sparing-Chávez (1998, 2012) characterizes =xankin as a marker of ‘immediate future’ whereas =katzi is treated as an ‘unspecified future’. I have not investigated the difference between these two aspect markers in detail, but the data I have collected are compatible with =xankin being more restricted in this way than =katzi. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | These TRMs are optional in the sense that they are not structurally required. However, when asked directly about whether these enclitics can be omitted in particular discourse contexts, speakers generally reject the sentences without the marker as infelicitous. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | The =tai form of the distant past marker appears in matrix clauses and occurs without the matrix past tense marker as discussed below. The =ti form appears in dependent clauses. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | The marker =nontu also appears to possibly be compatible with present tense and progressive aspect marking. The TRMs that indicate degree of future remoteness do not co-occur with past tense marking. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | The subsequent action switch-reference marker =xankin is sometimes pronounced with a glottal fricative initially (i.e., =jankin), as in (40). There appears to be no meaning difference associated with this variation, and I have never encountered an example where both pronunciations are not accepted when speakers are asked explicitly about it. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | As will be discussed shortly, there are two possible interepretations for TRMs in switch-reference clauses. It is clear why TRMs should be ruled out with simultaneous action switch-reference markers on the interpretation that is relative to the matrix event time. Since the simultaneous action switch-reference marker indicates that the events of the marked clause and the reference clause are simultaneous, this rules out a temporal lapse between them. On the reading where the TRM is interpreted relative to the utterance time, however, it is less obvious why TRMs should be incompatible with simultaneous switch-reference markers. One possibility is that in these cases the TRM in the marked clause would have to be redundant with a TRM in the reference clause in order for the simultaneity of events to hold. Realization of an obligatorily redundant TRM in the marked clause may be blocked for reasons of economy. A similar explanation may underlie other disallowed combinations of TRMs and switch-reference markers. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Sparing-Chávez (1998, 2012) only discusses the TRMs associated with past, not those associated with future events. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | The other argument provided by Cable (2013) comes from the use of TRMs with perfect aspect. In Amahuaca, the perfect marker =hax cannot co-occur with the past tense morphemes so it is not possible to replicate this second argument for Amahuaca. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||