Toeing the Party Line: Indexicality and Regional Andalusian Phonetic Features in Political Speech

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Linguistic Style and Political Speech

1.2. Andalusian Spanish Features

1.3. Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Corpus

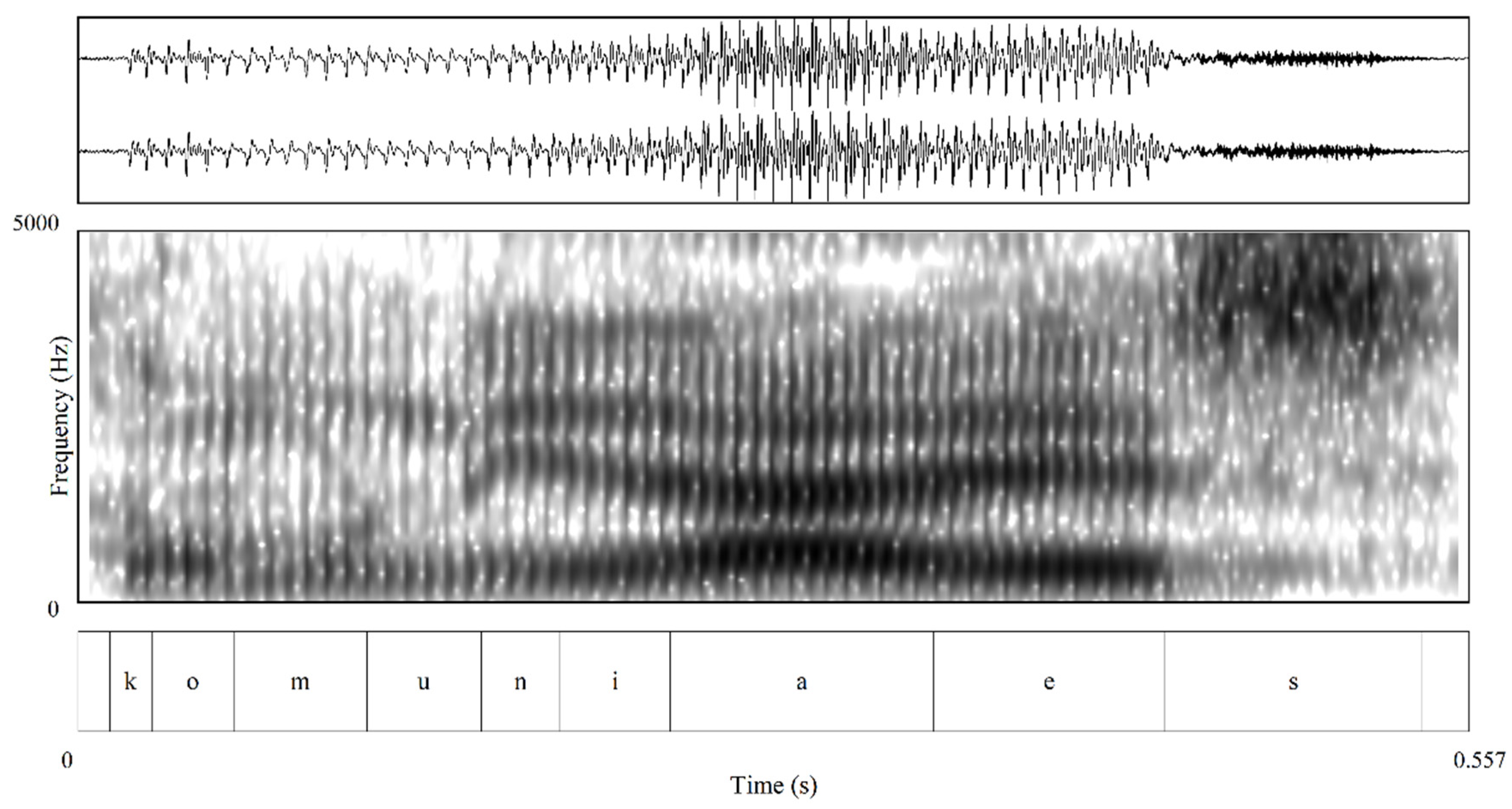

2.2. Dependent Variables

2.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Coda /s/

3.2. Word-Final Onset /s/

3.3. The Affricate /t͡ʃ/

3.4. Intervocalic /d/

3.5. Intra-Speaker Variation: The Case of José Antonio Pérez Tapias

4. Discussion

4.1. Social and Linguistic Norms in Andalusian Spanish

4.2. Individual Style-Shifting in Andalusian Spanish

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1. | Additionally, albeit anecdotally, the former Spanish Prime Minister Felipe González (1982–1996) is often referenced by Andalusians as one of the first major politicians to use Andalusian phonetic features in oral political discourse, granting them a higher degree of acceptability and prestige. |

| 2. | However, see Villena-Ponsoda and Vida-Castro (2020) for a description of an intermediate form blending Standard Castilian and AS in a type of koine mainly used by young urban speakers from the middle class. This shows an ongoing shift resulting from national education norms and regional varieties, yielding a novel variety gathering popularity across Andalusia and gaining acceptance particularly in Seville. |

| 3. | A reviewer notes that this may be the result of Pérez-Tapias’ time in Granada, a region where convergence with NCPS is more likely than in the west of Andalusia. Given his early exposure to Sevillian Spanish, connections to a cohort of politicians across Andalusia, and ongoing contact with the eastern variety through his career, this presents an interesting case study to see how these various factors in the politician’s life and background combine to inform his linguistic behavior and output. |

References

- Ahearn, Laura M. 2001. Language and Agency. Annual Review of Anthropology 30: 109–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, Marta M. 1998. Del uso sociolingüístico de las oclusivas posnucleares en el español peninsular norteño. Hispania 81: 949–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Alan. 1984. Language style as audience design. Language in Society 13: 145–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, Ana. 2004. Estudio sociolingüístico de Alcalá de Henares. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2022. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Program], Version 6.0.35, Retrieved 16 October 2021; Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Bucholtz, Mary, and Kira Hall. 2005. Identity and Interaction: A Sociocultural Linguistic Approach. Discourse Studies 7: 585–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupland, Nikolas. 2001. Language, situation, and the relational self: Theorizing dialect-style in sociolinguistics. In Style and Sociolinguistic Variation. Edited by Penelope Eckert and John R. Rickford. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ortiz, Rocío. 2019. El habla de los políticos andaluces en Madrid. Mantenimiento y pérdida del vernáculo andaluz. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ortiz, Rocío. 2022. Sociofonética andaluza. Caracterización lingüística de los presidentes y ministros de Andalucía en el Gobierno de España (1923–2011). Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Del Saz, María. 2019. From postaspiration to affrication: New phonetic contexts in western Andalusian Spanish. Paper presented at 19th ICPhS, Melbourne, Australia, August 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Campos, Manuel, Stephen Fafulas, and Michael Gradoville. 2018. Stable variation or change in progress? A sociolinguistic analysis of the alternation between para and pa. In Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 340, pp. 223–45. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 1989. The whole woman: Sex and gender differences in variation. Language Variation and Change 1: 245–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2008. Variation and the indexical field. Journal of Sociolinguistics 12: 453–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Molina, Elena. 2015. La influencia de la variable generación en la variación lingüística de Mérida (Badajoz). Análisis y resultados de nuevas actitudes. Revista de Investigación Lingüística 18: 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Molina, Elena. 2018. El habla de Mérida y sus cercanías. Nuevos tiempos y nuevos resultados. Anuario de letras. Lingüística y Filología 6: 119–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Molina, Elena. 2021. Estudio sociolingüístico de las intervenciones políticas y públicas de los presidentes del gobierno extremeño. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación 26: 167–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Molina, Elena, and Juan Manuel Hernández-Campoy. 2018. Geographic varieties of Spanish. In The Cambridge handbook of Spanish linguistics. Edited by Kimberly Geeslin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 496–528. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Tanya. 2014. A Socio-Phonetic Examination of Co-Articulation in Chilean Public Speech (Document No. AAI3665473). Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Tanya. 2018. Lexical Frequency Effects in Chilean Spanish Affricate Fronting. Southern Journal of Linguistics 41: 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- García-Marcos, Francisco Joaquín. 1990. Estratificación social del español de la Costa granadina. Almería: Departamento de Lingüística General y Teoría de la Literatura. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Peña, Noelia. 2004. Estudio sociolingüístico de la fonética de la ciudad de Madrid. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Alcalá, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Serrano, Antonio. 1994. Aspectos del Habla de Linares (Jaén). Malaga: University of Malaga. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Matthew, Paul Barthmaier, and Kathy Sands. 2002. Cross-linguistic acoustic study of voiceless fricatives. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 32: 141–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Lew, Lauren, Rebecca Starr, and Elizabeth Coppock. 2012. Style-shifting in the U. S. Congress: The vowels of “Iraq(i)”. In Style-Shifting in Public: New Perspectives on Stylistic Variation. Edited by Juan Manuel Hernández-Campoy and Juan Antonio Cutillas-Espinosa. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Lew, Lauren, Ruth Friskney, and James M. Scobbie. 2017. Accommodation or political identity: Scottish members of the UK Parliament. Language Variation and Change 29: 341–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjus, Jannis. 2017. Perceptual variety linguistics: Jerezano speakers’ concepts and perceptions of phonetic variation in western Andalusian Spanish. Loquens 4: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, Jonathan. 2007. Evidence for a relationship between synchronic variability and diachronic change in the Queen’s annual Christmas broadcasts. Laboratory Phonology 9: 125–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, Jennifer, Stefanie Jannedy, and Norma Mendoza-Denton. 1999. Oprah and /ay/: Lexical frequency, referee design and style. ICPhS 14: 1389–92. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, Nicholas. 2014. Sociophonetic analysis of phonemic trill variation in two sub-varieties of Peninsular Spanish. Journal of Linguistic Geography 2: 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez-Barahona, Marisol, and Darío Fuentes-Grandón. 2018. Realizaciones de los fonemas /t͡ʃ/ y /ʈ͡ʂ/ en el chedungun hablado por niños bilingües del alto Biobío: Un análisis espectrográfico. Literatura y Lingüística 37: 253–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Campoy, Juan Manuel, and Juan Antonio Cutillas-Espinosa. 2010. Speaker design practices in political discourse: A case study. Language and Communication 30: 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Campoy, Juan Manuel, and Juan Antonio Cutillas-Espinosa. 2013. The effects of public and individual language attitudes on intra-speaker variation: A case study of style-shifting. Multilingua 31: 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Campoy, Juan Manuel, and José María Jiménez-Cano. 2003. Broadcasting standardization: An analysis of the linguistic normalization process in Murcian Spanish. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7: 321–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero de Haro, Alfredo. 2017. The phonetics and phonology of Eastern Andalusian Spanish: A review of literature from 1881 to 2016. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura 22: 313–57. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero de Haro, Alfredo, and John Hajek. 2022. Eastern Andalusian Spanish. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 52: 135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, Nicole. 2017. “My Presiden(T) And Firs(T) Lady Were Black”: Style, Context, And Coronal Stop Deletion in The Speech of Barack And Michelle Obama. American Speech 92: 459–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hualde, José Ignacio, and Sonia Colina. 2014. Los Sonidos del español. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Daniel Ezra. 2009. Getting off the GoldVarb Standard: Introducing Rbrul for Mixed-Effects Variable Rule Analysis. Language and Linguistics Compass 3: 359–83. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Daniel Ezra. 2014. Progress in Regression: Why Natural Language Data Calls For Mixed-Effects Models. Available online: http://www.danielezrajohnson.com/ (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Kirkham, Sam, and Emma Moore. 2016. Constructing social meaning in political discourse: Phonetic variation and verb processes in Ed Miliband’s speeches. Language in Society 45: 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, William. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- López-Morales, Humberto. 1983. Estratificación social del español en San Juan de Puerto Rico. Mexico: Editorial Galache. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Butragueño, Pedro. 1995. La variable (s) en el sur de Madrid. Contribución al estudio de la frontera de las hablas meridionales del español. Anuario de Letras 33: 5–57. [Google Scholar]

- Melguizo-Moreno, Elisabeth. 2006. La fricatización de /č/ en una comunidad de hablantes granadina. Interlingüística 17: 748–57. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Martos, Isabel. 1998. La fonética de Toledo. Contexto geográfico y social. Alcalá de Henares: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alcalá. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Martos, Isabel. 2015. La variable sociolingüística /-s/ en el distrito de Vallecas (Madrid). In Patrones sociolingüísticos de Madrid. Edited by Ana M. Cestero-Mancera, Isabel Molina-Martos and Florentino Paredes-García. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Martos, Isabel, and Florentino Paredes-García. 2014. Sociolingüística de la elisión de la dental /d/ en Madrid (distrito de Salamanca). Cuadernos de Lingüística del Colegio de México. Estudios de cambio y variación 2: 55–114. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Fernández, Francisco. 2009. La Lengua Española en su Geografía. Madrid: Arco/Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Moya-Corral, Juan Antonio. 1979. La pronunciación del español en Jaen. Granada: University of Granada. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Martín, Ana María. 2003. Estudio sociolingüístico de El Hierro. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Las Palmas, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Podesva, Robert J. 2007. Phonation type as a stylistic variable: The use of falsetto in constructing a persona. Journal of Sociolinguistics 11: 478–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podesva, Robert J., Jermay Reynolds, Patrick Callier, and Jessica Baptiste. 2015. Constraints on the social meaning of released /t/: A production and perception study of US politicians. Language Variation and Change 27: 59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Matthew. 2022. Buenas no[tʃ]es y mu[ts]ísimas gracias: Variable Affricate Production in Peninsular Spanish Political Discourse [Conference Presentation]. Paper presented at the The 10th International Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics (WSS10), Georgia Tech, Atlanta, GA, USA, April 7–9; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363539486_Buenas_notes_y_mutsisimas_gracias_Variable_Affricate_Production_in_Peninsular_Spanish_Political_Discourse (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Pollock, Matthew. 2023. Performing Andalusian in Political Speech: Political Party And Sociophonetic Patterns Across Production And Perception. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Matthew, and Jamelyn A. Wheeler. 2022. Syllable-final /s/ and intervocalic /d/ elision in Andalusia: The Formation of Susana Díaz’s Regional Identity in Political Discourse. Language and Communication 87: 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Matthew, and Jamelyn A. Wheeler. 2023. Regional Variation and Speaker Design: A Sociophonetic Study of Galician Political Norms in Castellano [Conference Presentation]. Paper presented at the Forging Linguistic Identities, Towson University, MD, USA, March 17–18; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369365796_Regional_variation_and_speaker_design_A_sociophonetic_study_of_Galician_political_norms_in_Castellano (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Rama, José, Lisa Zanotti, Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte, and Andrés Santana. 2021. Vox: The Rise of the Spanish Populist Radical Right. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rincón-Pérez, Miguel Ángel. 2015. An acoustic and perceptual análisis of vowels preceding final /-s/ deletion in the speech of Granada, Spain and Cartagena, Colombia. Ph.D. dissertation, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Domínguez, María del Mar. 1997. Estudio sociolinguistico del habla de Melilla. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Martínez, Ana María. 2003. Estudio fonético del nordeste de la Comunidad de Madrid. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Samper-Padilla, José Antonio. 2011. Socio-phonological Variation and change in Spain. In The Handbook of Hispanic Sociolinguistics. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Samper-Padilla, José Antonio, and Humberto López-Morales. 1990. Estudio sociolingüístico del español de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Las Palmas: La Caja de Canarias. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Devyani. 2018. Style dominance: Attention, audience, and the ‘real me’. Language in Society 47: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Devyani, and Ben Rampton. 2015. Lectal focusing in interaction: A new methodology for the study of style variation. Journal of English Linguistics 43: 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, Sali A. 2012. Variationist Sociolinguistics: Change, Observation, Interpretation. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tejada-Giráldez, María de la Sierra. 2015. Convergencia y divergencia entre comunidades de habla: A propósito de la /s/ implosiva. Contribución al estudio de los patrones sociolingüísticos del español de Granada. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Torreira, Francisco, and Mirjam Ernestus. 2012. Weakening of intervocalic /s/ in the Nijmegen Corpus of Casual Spanish. Phonetica 69: 124–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vida, Matilde. 2004. Estudio sociofonológico del español hablado en Malaga. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés. 2013. Actos de identidad: ¿Por qué persiste el uso de los rasgos lingüísticos de bajo prestigio social? Divergencia geográfica y social en el español urbano de Andalucía. In Estudios Descriptivos y Aplicados Sobre el Andaluz. Edited by Rosario Guillén Stuil. Seville: The University of Seville Press, pp. 173–207. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés, and Antonio Manuel Ávila-Muñoz. 2014. Dialect stability and divergence in southern Spain. In Stability and Divergence in Language Contact: Factors and Mechanisms. Edited by Kurt Braunmüller, Steffen Höder and Karoline Kühl. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 207–38. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés, and Juan Antonio Moya-Corral. 2016. Variation of intervocalic /d/ in two speech communities (Granada and Malaga). A comparative analysis of an erosive phono-logical change. Boletín de Filología 51: 281–321. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés, and Matilde Vida-Castro. 2020. Variation, Identity and Indexicality in Southern Spanish: On the Emergence of a New Variety in Urban Andalusia. In Intermediate Language Varieties. Koinai and Regional Standards in Europe. Edited by Massimo Cerruti and Stavroula Tsiplakou. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 149–82. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés, Francisco Díaz Montesinos, Antonio Manuel Ávila Muñoz, and María de la Cruz Lasarte Cervantes. 2011. Interacción de factores fonéticos y gramaticales en la variación fonológica: La elisión de /d/ intervocálica en la variedad de los hablantes universitarios en la ciudad de Malaga. In Variación lingüística y contacto de lenguas en el mundo hispánico: In memoriam of Manuel Álvar. Edited by Yolanda Congosto Martín and Elena Méndez García de Paredes. Bogotá: Iberoamericana, pp. 311–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zimman, Lal. 2017. Gender as stylistic bricolage: Transmasculine voices and the relationship between fundamental frequency and /s/. Language in Society 46: 339–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phenomenon | Spanish Phrase “English Gloss” | Normative Production | AS Regional Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coda /s/ elision | las cosas “the things” | /las.ko.sas/ | [la∅.ko.sa∅] |

| Word-final onset /s/ elision | buenas ideas “good ideas” | /bue.na.si.ð̞e.as/ | [bue.na∅i̯.ð̞e.as] |

| Affricate fronting | muchos “many” | /mu.t͡ʃos/ | [mu.t͡sos] |

| Intervocalic /d/ elision | he comido “I have eaten” | /e.ko.mi.ð̞o/ | [e.ko.mi̯∅o] |

| Factor Type | Factor | Variant One | Variant Two | Variant Three | Variant Four |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coda /s/ Linguistic | Position (2) | Intervocalic onset /s/ | Coda /s/ | ||

| Syllables (2) | Monosyllabic | Polysyllabic | |||

| Preceding vowel height (3) | High | Mid | Low | ||

| Following phone (3) | Consonant | Vowel | Pause | ||

| Morphemic status (4) | Plural ending | Second sing. verbal use | Final non-inflectional | Other | |

| Word-final onset /s/ Linguistic | Position (2) | Intervocalic onset /s/ | Coda /s/ | ||

| Syllables (2) | Monosyllabic | Polysyllabic | |||

| Preceding vowel height (3) | High | Mid | Low | ||

| Following phone (3) | Consonant | Vowel | Pause | ||

| Morphemic status (4) | Plural ending | Second sing. verbal use | Final non-inflectional | Other | |

| /t͡ʃ/ Linguistic | Preceding vowel height (3) | High | Mid | Low | Consonant |

| Following vowel height (3) | High | Mid | Low | ||

| Lexical stress (2) | Yes | No | |||

| /d/ Linguistic | Preceding phone height (3) | High | Mid | Low | |

| Following phone height (3) | High | Mid | Low | ||

| Grammatical function (4) | Participle | Adjective | Unstressed other | Stressed other | |

| Extralinguistic | City (4) | Seville | Cordoba | Madrid | Malaga |

| Gender (2) | Male | Female | |||

| Political party (2) | Socialist (PSOE) | Conservative (PP) | |||

| Context (3) | Interview: same-gender interlocutor | Interview: opposite-gender interlocutor | Prepared speech | ||

| Random effect | Speaker (32) | ||||

| Party/Gender | Cordoba | Malaga | Seville | Madrid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 6.6% | 14.3% | 5.4% | 90.0% |

| Female | 8.4% | 20.5% | 4.0% | 94.3% |

| Male | 4.8% | 9.9% | 6.7% | 85.6% |

| Socialists | 15.1% | 5.9% | 13.4% | 94.3% |

| Female | 18.4% | 1.6% | 7.4% | 96.0% |

| Male | 11.1% | 9.4% | 19.5% | 92.6% |

| Total | 11.1% | 10.3% | 9.4% | 92.1% |

| Factor | Log-Odds | Tokens | Percent | Factor Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Madrid | 4.527 | 1197 | 92.1% | 0.989 | |

| Malaga | −1.262 | 1135 | 11.1% | 0.221 | |

| Cordoba | −1.618 | 1040 | 10.4% | 0.165 | |

| Seville | −1.648 | 1194 | 9.4% | 0.161 | |

| Range | 82.8 | ||||

| Following phone (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Pause | 2.078 | 680 | 41.0% | 0.889 | |

| Voiceless stop ([p], [t], [k]) | 0.353 | 2490 | 32.9% | 0.587 | |

| Voiced stop ([b], [d], [g]) | 0.162 | 636 | 30.2% | 0.540 | |

| Nasal ([n], [m]) | −0.174 | 389 | 23.1% | 0.457 | |

| Fricative ([x], [θ], [f]) | −0.335 | 101 | 22.8% | 0.417 | |

| Liquid ([l], [ɾ]) | −2.085 | 270 | 15.9% | 0.111 | |

| Range | 77.8 | ||||

| Morphology (p = 0.032) | |||||

| Non-morphemic | 0.502 | 2041 | 34.9% | 0.623 | |

| Verb | −0.067 | 555 | 29.7% | 0.483 | |

| Plural | −0.435 | 1970 | 26.7% | 0.393 | |

| Range | 23 | ||||

| Context (p = 0.014) | |||||

| Scripted speeches | 0.225 | 1545 | 33.0% | 0.556 | |

| Same-gender interlocutor | −0.056 | 1487 | 31.5% | 0.486 | |

| Different-gender interlocutor | −0.169 | 1534 | 30.6% | 0.458 | |

| Range | 9.8 | ||||

| n = 4566 df = 14 Log-likelihood = −1155.9 R2 fixed = 0.641 R2 total = 0.737 | |||||

| Party/Gender | Cordoba | Malaga | Seville | Madrid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 27.8% | 26.0% | 19.7% | 98.3% |

| Female | 28.2% | 40.3% | 20.3% | 99.3% |

| Male | 27.4% | 14.9% | 19.0% | 97.3% |

| Socialists | 45.4% | 14.1% | 33.0% | 99.0% |

| Female | 52.7% | 8.4% | 19.9% | 99.3% |

| Male | 35.5% | 18.7% | 45.9% | 98.6% |

| Total | 36.8% | 20.2% | 26.3% | 98.6% |

| Factor | Log-Odds | Tokens | Percent | Factor Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Madrid | 4.800 | 589 | 98.6% | 0.992 | |

| Cordoba | −1.148 | 508 | 36.8% | 0.241 | |

| Seville | −1.806 | 589 | 26.3% | 0.141 | |

| Malaga | −1.847 | 554 | 20.2% | 0.136 | |

| Range | 85.6 | ||||

| Grammatical function (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Non-morphemic | 1.751 | 737 | 69.6% | 0.852 | |

| Plural | −0.868 | 958 | 36.8% | 0.296 | |

| Verb | −0.882 | 545 | 31.0% | 0.293 | |

| Range | 55.9 | ||||

| n = 2240 df = 7 Log-likelihood = −715.8 R2 fixed = 0.689 R2 total = 0.769 | |||||

| Party/Gender | Cordoba | Malaga | Seville | Madrid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 90.3% | 87.7% | 100.0% | 90.2% |

| Female | 88.4% | 75.5% | 100.0% | 86.2% |

| Male | 92.0% | 98.2% | 100.0% | 94.4% |

| Socialists | 87.4% | 79.2% | 83.3% | 93.0% |

| Female | 77.2% | 58.7% | 69.4% | 98.3% |

| Male | 100.0% | 95.0% | 100.0% | 87.7% |

| Total | 88.8% | 83.5% | 91.8% | 91.6% |

| Factor | Log-Odds | Tokens | Percent | Factor Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Male | 1.088 | 436 | 95.9% | 0.748 | |

| Female | −1.088 | 432 | 82.2% | 0.252 | |

| Range | 49.6 | ||||

| Preceding phone height (p < 0.001) | |||||

| High (/i/, /u/) | 0.910 | 434 | 95.2% | 0.713 | |

| Low (/a/) | 0.877 | 21 | 91.9% | 0.706 | |

| Mid (/e/, /o/) | −0.233 | 355 | 88.2% | 0.442 | |

| Sonorant (/r/, /n/) | −1.554 | 58 | 70.7% | 0.175 | |

| Range | 53.83 | ||||

| Context (p = 0.019) | |||||

| Different-gender interlocutor | 0.564 | 289 | 92.1% | 0.637 | |

| Same-gender interlocutor | −0.149 | 272 | 89.7% | 0.463 | |

| Scripted speeches | −0.415 | 307 | 85.3% | 0.398 | |

| Range | 23.9 | ||||

| Following phone height (p = 0.007) | |||||

| High (/i/, /u/) | 0.612 | 68 | 98.5% | 0.648 | |

| Mid (/e/, /o/) | 0.285 | 504 | 92.1% | 0.571 | |

| Low (/a/) | −0.898 | 296 | 81.8% | 0.290 | |

| Range | 35.8 | ||||

| Lexical stress (p = 0.006) | |||||

| Yes | 0.769 | 140 | 95.7% | 0.683 | |

| No | −0.769 | 728 | 87.8% | 0.317 | |

| Range | 36.6 | ||||

| n = 868 df = 11 Log-likelihood = −198.1 R2 fixed = 0.245 R2 total = 0.687 | |||||

| Party/Gender | Cordoba | Malaga | Seville | Madrid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 65.2% | 72.4% | 76.1% | 72.7% |

| Female | 70.4% | 67.2% | 78.4% | 82.0% |

| Male | 60.0% | 76.3% | 73.8% | 63.3% |

| Socialists | 78.8% | 76.3% | 70.1% | 69.6% |

| Female | 78.0% | 85.8% | 70.3% | 71.1% |

| Male | 79.8% | 68.7% | 70.0% | 68.0% |

| Total | 72.1% | 74.3% | 73.1% | 71.1% |

| Factor | Log-Odds | Tokens | Percent | Factor Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Scripted speech | 0.910 | 771 | 86.4% | 0.713 | |

| Different-gender interlocutor | −0.323 | 770 | 66.9% | 0.420 | |

| Same-gender interlocutor | −0.586 | 726 | 64.2% | 0.358 | |

| Range | 35.5 | ||||

| Following phone height (p < 0.001) | |||||

| High (/i/, /u/) | 0.498 | 134 | 82.1% | 0.622 | |

| Low (/a/) | −0.012 | 702 | 76.8% | 0.497 | |

| Mid (/e/, /o/) | −0.486 | 1431 | 69.7% | 0.381 | |

| Range | 24.1 | ||||

| Preceding phone height (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Mid (/e/, /o/) | 0.400 | 352 | 78.4% | 0.599 | |

| High (/i/, /u/) | 0.097 | 985 | 75.4% | 0.524 | |

| Low (/a/) | −0.497 | 930 | 67.5% | 0.378 | |

| Range | 22.1 | ||||

| Syllable count (p = 0.016) | |||||

| Monosyllabic | 0.386 | 65 | 78.5% | 0.595 | |

| Polysyllabic | −0.386 | 2202 | 72.5% | 0.405 | |

| Range | 19 | ||||

| Grammatical function (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Adjective | 0.427 | 373 | 79.6% | 0.605 | |

| Participle | −0.113 | 585 | 71.6% | 0.472 | |

| Other | −0.315 | 1309 | 70.6% | 0.422 | |

| Range | 18.3 | ||||

| n = 2267 df = 11 Log-likelihood = −1200.3 R2 fixed = 0.148 R2 total = 0.215 | |||||

| Phenomenon | Pérez Tapias | Andalusian PSOE | Andalusian PP | Madrid PSOE | Madrid PP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coda /s/ retention | 36.7% | 9.4% | 8.5% | 94.3% | 90.0% |

| Word-final onset /s/ retention | 69.3% | 26.9% | 24.1% | 99.0% | 98.3% |

| Intervocalic /d/ retention | 29.30% | 24.70% | 28.40% | 30.50% | 27.30% |

| Post-alveolar /t͡ʃ/ production | 100.0% | 81.8% | 93.1% | 93.0% | 90.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pollock, M. Toeing the Party Line: Indexicality and Regional Andalusian Phonetic Features in Political Speech. Languages 2023, 8, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030196

Pollock M. Toeing the Party Line: Indexicality and Regional Andalusian Phonetic Features in Political Speech. Languages. 2023; 8(3):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030196

Chicago/Turabian StylePollock, Matthew. 2023. "Toeing the Party Line: Indexicality and Regional Andalusian Phonetic Features in Political Speech" Languages 8, no. 3: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030196

APA StylePollock, M. (2023). Toeing the Party Line: Indexicality and Regional Andalusian Phonetic Features in Political Speech. Languages, 8(3), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030196