1. Introduction

It is often the case, in histories of persecution, that the tactics that oppressed groups assume for their survival get caricatured by the ruling class or caste and serve to further rationalize discrimination against the former. One only needs to think of the economic specialization of Jews under medieval Christian rule, the linguistic ingenuity of formerly enslaved and colonized people, or the unsanctioned border transits spurred on by the economic and social conditions of imperialism. It is not uncommon for such tactics to be reified by the erstwhile oppressed, and thereby take on lives quite apart from their original purposes, thus being inducted as a part of the respective group’s “culture”.

Taqiyya as practiced in the various traditions of Shi‘ism presents an exemplary site for studying this phenomenon. In the broadest sense,

taqiyya denotes practices of circumscription and dissimulation that are prescribed in the Qur’an for all Muslims when their safety and that of their communities are at risk.

1 This concept gets especially high mileage within Shi‘i traditions, notably in the branch of Shi‘ism known as Isma‘ilism. For Isma‘ilis, secrecy and dissimulation serve the end of protecting both the believers as well as the belief from the perils of exposure to the uninitiated. The practice of

taqiyya, owing to its embeddedness in the theology and normative epistemology of Isma‘ilis, has shown remarkable durability even as the fortunes of Isma‘ili communities have changed. This article examines one such case of changing fortunes, narrated through ethnographic interviews with Isma‘ilism whose origins lay in Saudi Arabia’s southern region of Najran.

The subjects of our study hail from the Sulaymani branch of Isma‘ilism. Though headquartered and concentrated in Saudi Arabia’s southern province of Najran, the community traditionally extends into northern Yemen and western South Asia, and in contemporary times, community members pursue employment and education across the country and the world. The Sulaymani Isma‘ili community has been affected by the country’s sweeping social reforms that began in 2016. In an ironic turn, the state’s move toward a rhetoric of outward tolerance and coexistence has inspired something of an existential crisis for a group that, over its millennium-long existence, has been little acquainted with such courtesies. This tension is evident in how our interlocutors disagreed as to whether or not Isma‘ili practices had become maladaptive in the face of the changing social and political atmosphere of the country. Their opposing narrative unfolding shows how continuities and ruptures in the social conditions that motivated taqiyya have contributed to divergent understandings of the meaning and continued utility of the practice not only between individuals but also (and especially) between generations.

Our interviewees’ divergent positions were typically constructed against the spatial and temporal backdrop of pre- and post-reform Saudi Arabia, with the seminal years of 2000 and 2016 being iconic of the respective eras. In this paper, we employ Mikhail

Bakhtin’s (

1981) heuristic of the chronotope for understanding the unique conditions of validity established through the discursive invocation of these time–space contexts. While the notion of chronotope was developed within literary theory, the concept has enjoyed broad appeal in the social sciences (

Babel 2022;

Barrett 2017;

Blommaert 2015;

Britt 2018;

De Fina et al. 2017;

Dick 2010). This appeal is due to the fact that chronotopes serve as both frames for discourse as well as discursive objects that enable and constrain agency over the speakers’ construction of personae via stancetaking (

Woolard 2013). Those interviewed consistently employed frames of “then” and “now” to ground contrastive meanings of

taqiyya. Participants aligned themselves morally, affectively, and instrumentally toward or against particular spatiotemporally grounded understandings of

taqiyya: Some cast the concept in a positive light as an immutable religious imperative in addition to being an important self-preservation tactic; other (typically younger) participants viewed

taqiyya as a hindrance to the transmission of knowledge within the Isma‘ili community, and ultimately a threat to the community’s survival. We take these divergent understandings to be anchored to two watershed moments in Saudi and Isma‘ili history. The first is the politico-religious upheaval in Najran in 2000 that triggered significant changes both internally within the Isma‘ili community and with regard to Najran’s degree of autonomy. The second moment is the social reforms, initiated by Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman in 2016, which were an about-face from the policies of the previous several decades. These events, which had significant social consequences for Isma‘ilis in Saudi Arabia, while counterposed on the face, have forced Isma‘ilis to figure out how to orient themselves with regard to the emergent citizenship categories in Saudi Arabia. Specifically, individuals have to reckon with which aspects of longstanding Isma‘ili practices are essential and immutable, and which are situational.

In the next subsection, we summarize some of the differences in Isma‘ili practices vis-a-vis their Sunni neighbors. In the subsequent subsection, we give a succinct overview of the concept of

taqiyya within Shi‘ism in general, and within Isma‘ilism in particular. We pay special attention to the mechanisms by which

taqiyya is socialized and perpetuated, examining its function as an ethical and epistemic ground for a range of behaviors. As a nod to future research, we also deal briefly with the way in which

taqiyya, in its specifically Isma‘ili vernacular form, is cultivated in and through a larger culture of privacy that predominates in Peninsular Arab

2 societies and is not specifically religious in character. The practical basis for Isma‘ili

taqiyya in Arab family life contributes to its ability to sometimes go unnoticed by Isma‘ilis themselves, even as they continue to enact it routinely. The latter fact comes to the fore most clearly in the following interviews with Reem and especially with Bayan, who identified the reason for her persistent practice of

taqiyya in “habit” and “how [she] was raised”. The transcription conventions for all Arabic words used in this paper are found in

Appendix A.

1.1. Taqiyya

In the broader Islamic tradition, the term

taqiyya denotes the practices of circumscription and dissimulation, which are prescribed for Muslims when their safety and that of their communities are at risk. The term, and the tactics to which it refers, come from the Qur’an and thereby constitute a universal precept within Islamic orthodoxy. Among scholars and within everyday religious discourse, however, the term takes on a charged association with Shi‘a traditions, an association that has accumulated over centuries through anti-Shi‘a polemics. The ready availability of

taqiyya as ammunition against Shi‘ism is due to the relative importance of the concept in the Shi‘a tradition. For the two major branches of Shi‘ism, Twelverism and Isma‘ilism, the notion of

taqiyya is extended far beyond mere situational expedient in the face of danger to form a central component of Shi‘i theology and piety (

Kohlberg 1995, p. 345). This is especially true for Isma‘ilism, where the concept is bound to normative epistemology founded on a highly sophisticated esotericism. The term

bāṭiniyya (esotericism), which has long been used disparagingly as an epithet for Isma‘ilism (See

de Jong and Radtke (

1999) and

McCarthy (

1980) for examples), is founded on the religion’s approach to scriptural interpretation. Whereas literalism predominates among Saudi’s majority school of jurisprudence, Isma‘ili hermeneutics, by contrast, is characterized by a particularly elaborate form of hierarchized interpretation wherein the apparent (ẓ

āher) meaning of the Qur’an is subordinate to the many levels of truer hidden (

bāṭin) meaning. Access to esoteric knowledge is granted only by permission of the da‘i, the community’s spiritual leader, or one of his representatives, pending the attainment of the requisite knowledge through rigorous study (

Andani 2016;

Bowen 2015;

Qutbuddin 2010). It is a commonly held belief in Najran that unsanctioned dissemination of esoteric knowledge can drive the uninitiated to insanity, and at the same time inspire unbelief, persecution, and profanation of sacred knowledge. To this point,

Amir-Moezzi (

2017, p. 5) emphasized early Isma‘ili Ḥamd al-Dīn al-Kirmānī’s invocation of the biblical adage “do not cast your pearls before swine” as a justification for

taqiyya. It is this fact, the necessity to protect not only believers but also the belief, that distinguishes

taqiyya in the Isma‘ili tradition from its more tactical and expedient analog in Islam more generally.

While the present work deals primarily with

taqiyya in discourse, it is important to note that

taqiyya extends beyond discourse to form an important component of an Isma‘ili

habitus (

Bourdieu 1984).

3 Taqiyya, as a practice or disposition, constitutes a structuring force that, by virtue of its own immanent logic, has a tendency to occlude itself in addition to its target object (e.g., religious identity mediated by prayer style, dress, family, or tribe name, etc.). To understand how

taqiyya manages to have such a pervasive influence on Isma‘ili comportment while at the same time having such a limited presence in Isma‘ili discourse requires an understanding of the broader ideologies of secrecy that are characteristic of Arab family life in the Arabian Peninsula. Through their reinscription as

taqiyya, existing norms around privacy take on a strong theological valence, and what can be readily thematized and discussed as being

taqiyya as such is only the tip of the iceberg in a large complex of practices, behaviors, and dispositions that conspire toward concealment, and for which the pious and the worldly motivations are inextricable.

4 A strong imperative toward domestic privacy, which is held in common by the vast majority of Peninsular Arab communities irrespective of religion, forms the foundation upon which

taqiyya can melt into the background of social life. By attaching religious value to a preexisting disposition toward privacy, Isma‘ilism derives a strong moral and epistemological basis for

taqiyya’s role in informing behavior and ethical reasoning.

In the following subsections, we give a very brief overview of particularities in Isma‘ili practice that are most salient in the Saudi Arabian context: prayers and timekeeping. These practices have been among the principal objects of

taqiyya, as will emerge in the interviews. In

Section 1.4, we look at

asrār al-bayt (lit. ‘secrets of the house’) and in doing so, turn from differences in Isma‘ilism to cultural commonalities shared broadly across the Arabian Peninsula. In that subsection, we show how the practice of

taqiyya depends on endowing spiritual and religious valence to a general ethic of privacy in the region. This helps to explain why the Saudi Isma‘ili practice of

taqiyya does not rely on a highly self-conscious notion of religious identity. The implications and future directions opened by these observations will be addressed in the discussion section.

1.2. Isma‘ili Prayers

Prayer rituals in Islam are derived from a combination of emulation and explicit direction by the Prophet Muhammad. The differences in prayer rituals between the various schools of Islamic jurisprudence are, to a non-Muslim onlooker, quite subtle and can be accounted for by variations in the Prophet’s own practices. These differences are not necessarily larger between Sunnis and Shi‘i than they are between the four main schools (

madhāhib, sg.

madhhab) of Sunnism. Keeping one’s arms relaxed at their sides rather than interlocking them in front of their body is taken as emblematic of Shi‘ism in much of the Muslim world even though it is not in any sense exclusive to Shi‘ism. The more conspicuous features that are present in the larger sect of Twelver Shi‘ism—like prostrating on a

turbah (a stone or piece of earth), and the loudly-spoken

ṣalawāt at the conclusion of the prayer cycle—are absent from Isma‘ilism.

5 For Isma‘ilis, differences in spoken prayers are generally said under the breath in such a way that they would not usually be noticed by anyone apart from the person saying them. In the context of Saudi Arabia, the combination of the worshipper’s profiling as Saudi and their keeping their hands at their side would be sufficient to signal to most lay Muslims that the worshipper is Shi‘i.

1.3. The Isma‘ili Calendar

A difference that is particular to the sects of Isma‘ilism in the Fatimid tradition (i.e., Sulaymani, Dawoodi Bohra, and a few smaller sects all based in South Asia and Arabia) is their adherence to an astronomically sophisticated fixed tabular calendar rather than the calendar that predominates in the rest of the Arabian Peninsula (

Daftary et al. 2012). While both are lunar in terms of calculating the year, the latter is dependent on direct visual observation of the moon, which leads to occasional one-to-two-day disparities in dates. The disparities are most socially fraught when they occur during Ramadan and Eid, heralding month-long fasting and celebration, respectively. As will be discussed with reference to the interviews, differences in the calendar have been a significant object of Isma‘ili concealment. In years when the Isma‘ili fasting period begins before that of the Sunnis, community members will sometimes do things to draw attention away from the fact that they are fasting, for example bringing and displaying food that they do not intend to eat. As we discuss later in the paper, the advent of social media and the recent changes in Saudi society have meant that comments on these cultural differences—once rather fraught—have taken on a somewhat more humorous tenor, with Saudis making light of contrasts through the use of hashtags and memes.

1.4. Household Privacy

A video clip went viral in 2020 showing a Saudi reporter at a cultural festival asking a child (who was evidently from the countryside based on his wearing a traditional

shamagh and

thawb and speaking in a markedly rural variety of Arabic) if he had eaten with his family at the fairgrounds.

6 His terse response,

ma adri, “I don’t know”, was comical because any Saudi viewer would recognize it at once as absurd and infelicitous and at the same time completely relatable: the laconic child was indisputably satisfying social expectations that were familiar to the audience and rendering those expectations visible and public. The genre of the candid television news interview played no small part in the humor as it was emblematic of the stark juxtaposition of a new post-reform Saudi Arabia characterized by novel forms of stranger sociality with the old, where familial affairs are not to be shared with other kin, much less strangers. The child’s diligent and instinctive commitment to his family’s privacy, even in trivial matters such as if they had eaten, is an excellent demonstration of the general social expectations in the Arabian Peninsula, which undergird the specifically Isma‘ili practice of concealment. In Peninsular Arab societies, divulging information about household affairs is strongly proscribed. This ideology is made manifest in the architecture: on the exterior, high walls surrounding houses prevent visual and physical access, while in the interior, Arabian houses are characterized by separate private spaces designated for various social purposes and occupied by various social actors: close family, relatives, female guests, and male guests (

Sobh and Belk 2011). Household members are taught from a young age that internal matters are not shared outside the house or with guests. One of our participants recalls that careless comments about “private matters”—such as those universally characteristic of young people’s talk—to anyone outside of the immediate household would be met with a searing glance or a pinch from her mother, discreetly signaling some impending rebuke once the latter’s face was no longer at stake. Though concerns over household privacy are common across cultures, the topics prohibited are broad, encompassing almost any internal house affair: recent purchases, however minor; a family member’s travels; a broken glass; some household cleaner that was spilled on the kitchen floor last month. The participant reported that she never understood immodesty as motivating her mother’s rebukes. The term that was used to denote these off-limit topics was

asrār al-bayt, “secrets of the house”, and her mother’s glares and scolding, the consequences for exposing these secrets, were oriented toward inspiring fear and better behavior but never bore the expressed intent nor the effect of inspiring guilt or shame.

When individuals from the community are confronted with questions about home matters, indirection is preferable (as with the child from the video’s response: ma adri “I don’t know”) to the alternative of telling innocuous untruths. However, given the minefield of things that fall into the category of asrār al-bayt, candor concerning any matter that registers as vaguely private is risky and usually avoided. Therefore, Isma‘ili children never have to make much of a conscious effort to cultivate taqiyya in its specifically religious idiom, as indirection and dissimulation translate seamlessly from asrār al-bayt to asrār ad-dīn (that is, from “secrets of the house” to “secrets of the faith”). We might say that these two types of secrecies feature as two poles on a continuum that serve to reinforce one another. Asrār al-bayt, which is not at all exclusive to the Isma‘ilis, serves as a foundation for the specifically Isma‘ili imperative to secrecy around issues of faith. At the same time, taqiyya qua pious circumscription spills over into affairs that do not obviously pertain to matters of faith. What is a matter of faith and what is not is seldom easily discernible, as supposed matters of faith can be reframed as matters of familial life and vice versa through the semiotic processes of recursivity and erasure. For example, whether concealing when and how one’s family prays or fasts should be considered a part of asrār al-bayt or asrār ad-dīn (and thus whether it should be considered an act of taqiyya or as a more general non-denominational sort of privacy) is often ambiguous.

2. Methods

To explain the social meanings of

taqiyya across time–space configurations, this study employs ethnographic sociolinguistic interviews in which participants were encouraged to narrate personal stories about their past and present practices of

taqiyya. Each interview was one hour long, and they were all in Najrani Arabic. The first author, a native Najrani Arabic speaker, translated the interviews into English and transcribed them based on

Jefferson’s (

2004) Conversational Analysis transcription system (see

Appendix B). The first author’s status as a community member and her close relationship with all of the participants facilitated her access to the community and made for relative ease in discussing Isma‘ili beliefs and practices.

We follow the lead of Katherine

Woolard (

2013) and Jane

Hill (

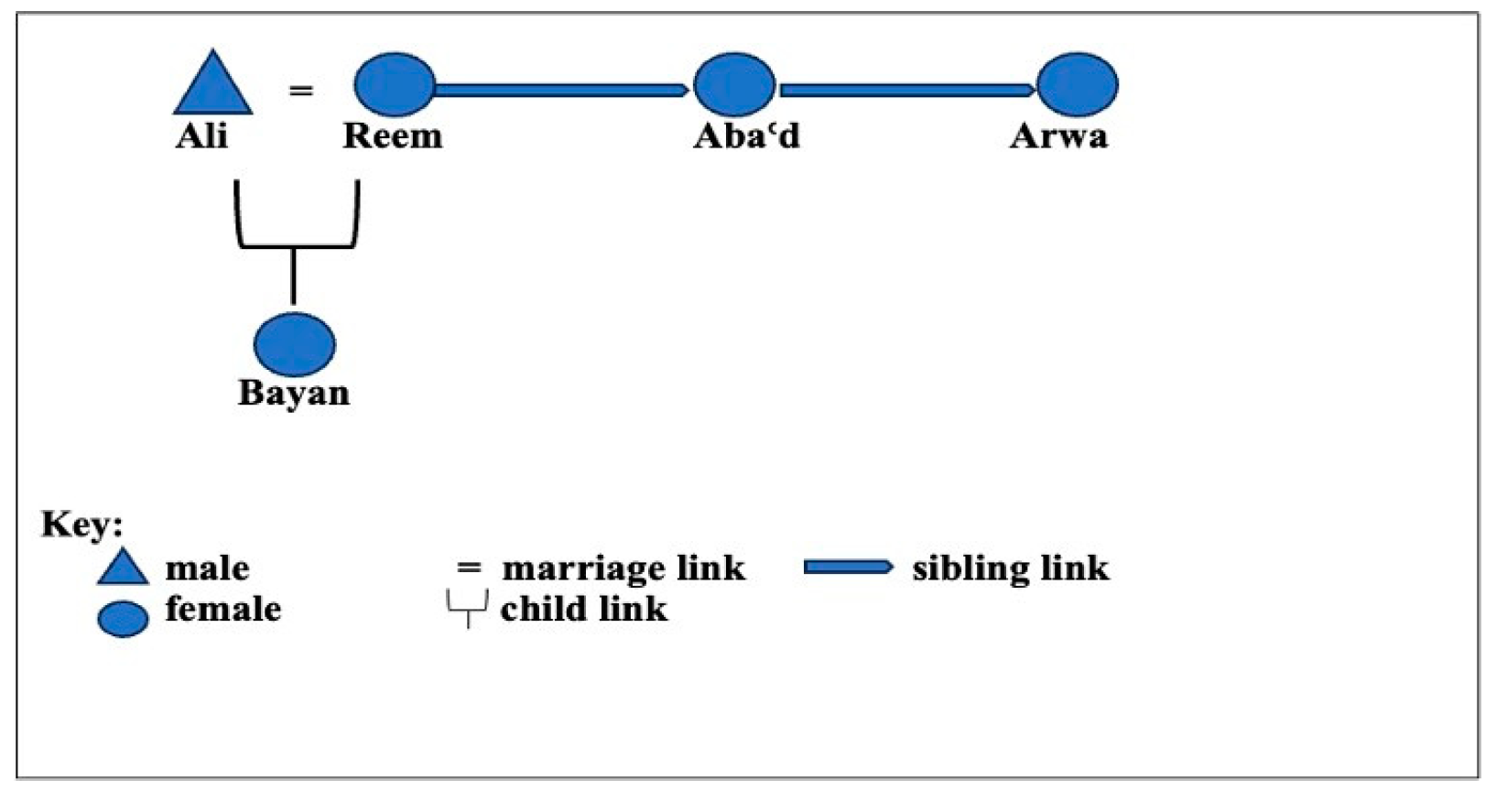

1995) who have employed Bakhtinian analysis to reveal the immanent metasemiotic frames of space–time and “voice” in the constitution of discourse. The tools developed by Bakhtin for qualitative research are effective even when dealing with a small handful of interviews (Woolard’s study has five participants, and Hill’s well-known essay is based on a single interview with a community elder). In the present study, we have five. The participants in our sample are from two generations of relatives, five subjects total, all from a similar middle socioeconomic class. We used judgment sampling to select participants. We targeted individuals within the Isma‘ili home territory of Najran on the country’s southern border with Yemen and individuals living in the relatively more cosmopolitan areas in the Hejaz along the Red Sea coast. Their relationship is shown in

Figure 1. All names as presented in this study are fictional.

We found it useful to explain the interviewees’ narratives of their

taqiyya experience based on

Bakhtin’s (

1981) concept of the chronotope, a term that refers to the spatiotemporal configuration in which narratives and other forms of speech take place (e.g., historical period, a moment of narration, or imaginary future time). The interviews presented two distinct chronotopes that shape the informants’ social meaning of

taqiyya. The first one is the chronotope of cyclic time and timeless religious practice. It refers to the narratives that recirculate the immutable meaning of

taqiyya in the present spatiotemporal configuration. This chronotope indexes piety, community preservation, and/or social relations. The second one is the chronotope of the present. It refers to the narratives that reject the past utility of

taqiyya due to the change in social conditions. This chronotope indexes a negative stance toward

taqiyya as a practice that does not serve the community in the present time.

3. The Past: Tradition, Protection, and Continuity

The first three participants, Reem, Ali, and Bayan, represent the kind of Isma‘ili speakers who hail the new social–political reforms and take a positive stance toward the new social conditions. They recognized that the reality they currently exist in is a world apart from the past one in which they were compelled by necessity to practice

taqiyya of the type that

Kohlberg (

1995) calls “prudential

taqiyya”, that is,

taqiyya for self-preservation (contrasted with “non-prudential

taqiyya” concerned with matters of faith and the control over the circulation of knowledge). At the same time, they recognize that their community owes its well-being to the practice of

taqiyya and that the time will inevitably come when it must be employed again. The aspect of

taqiyya which pertains to community organization and hierarchy was still relevant for these participants in their youths. For this reason, whether they began their study of esoteric knowledge prior to the 2000 moratorium, like Ali, or were merely in the company of those who had,

taqiyya’s ties to spirituality are more obvious and intimate than for the younger participants. All three of these interviewees demonstrated continuity in their understanding of the meaning of

taqiyya. Importantly, however, their understanding was not limited to precautionary dissimulation toward outsiders, but also to the prohibitions around sharing knowledge within the community. By preserving this dual meaning, these participants are able to make the connection between

taqiyya’s theological and practical aspects. Maintaining the former makes it easier to conceive of

taqiyya as a cardinal principle of the Isma‘ili religion. All three of these participants referenced, directly or indirectly, the

da‘i and the Isma‘ili canon in establishing their stance toward

taqiyya.

3.1. Interview 1: Reem

The first case study, Reem, was a 53-year-old woman. She lived her childhood and part of her adulthood in Najran City and then moved to the Hejaz region with her husband and children in 1992. She worked as a primary school teacher for over 30 years. Reem talked about her childhood in Najran City from a nostalgic perspective of time and place. When she was in Najran City, Isma‘ilis, Sunnis, Zaydis, and other denominations coexisted. She stated, “In the past, we were all one. We knew we had slightly different practices, yet we did not feel we were different from each other”. We asked Reem how and when things changed, and she reported that after she moved to Hejaz in the early 1990s, she was exposed to anti-Shi‘i rhetoric in her workplace and public media. She decided to conceal her Isma‘ili identity and practices, particularly fasting and praying, to mitigate risk and maintain social relations.

In the following excerpt, Reem’s explanation of

taqiyya was articulated in reference to (a) various past events in which Isma‘ilis (and other Shi‘a communities) faced social discrimination, (b) Isma‘ili religious imperative discourse, and (c) Isma‘ili figures.

| 1 | AA | would you consider this [your concealment practice] taqiyya? |

| 2 | Reem | ah:: we would consider it ((taqiyya)) (.) we would always consider it taqiyya. |

| 3 | AA | yeah. |

| 4 | Reem | yeah (.) they always told us to have patience, “keep taqiyya”, and “taqiyya is half of the religion” |

| 5 | AA | hmm |

| 6 | Reem | why?↑ so that no one would harm us |

| 7 | AA | yeah |

| 8 | Reem | because, at that time, you may get hurt↑ a person may get big problems, you know. |

In our conversation, Reem stated repeatedly, (“Keep taqiyya”, and “taqiyya is half of the religion” (4)). In voicing these oft-repeated maxims from the da‘i and from the Isma‘ili canon, Reem is shifting her participatory role from the author of the talk to the animator (i.e., using her voice to produce the speech of others) and the principal (the person responsible for the message). Reem’s use of these voices expands what taqiyya means to her. It is a collective call to protect the community and the faith in a time–space where being publicly known as Isma‘ili (or Shi‘i in general) is risky and dangerous “because, at that time, you may get hurt, and a person may have big problems” (8).

Reem explained that her non-Isma‘ili friends/colleagues who have been working with her for over 30 years might know that she is Isma‘ili, but they would not discuss theological matters with her. Practicing

taqiyya over time (avoiding religious topics, concealing her Isma‘ili identity, silence, and accommodating her religious practices to non-Isma‘ilis) allowed her to avoid theological inquisitive questions and difficult explanations, and at the same time, she has been able to maintain social relations with non-Isma‘ilis.

| 9 | Reem | Now they won’t say (.) they won’t say anything ((anti-Shi‘a discourse)) in front of us ((Isma‘ilis)). The system, ah, we created by avoiding these kinds of discussions = I mean we protected ourselves from these ((theological)) discussions. |

| 10 | Reem | even if they opened a ((theological)) conversation with me, I do not have information. |

| 11 | AA | hmm |

| 12 | Reem | I do not have knowledge to explain; I do not have Isma‘ili theological knowledge↑ |

| 13 | AA | Why do you not have Isma‘ili knowledge? |

| 14 | Reem | because of ah taqiyya. No one can just open a book and read. No one around you can teach you. |

People around Reem would not use anti-Shi‘i rhetoric in her presence or try to start a conversation about her practices or faith: “The system, ah, we created by avoiding these kinds of discussions. we protected ourselves from these [theological] conversations” (9). She added that even if they initiated a conversation with her, she would not have enough Isma‘ili theological knowledge to pursue the discussion. As mentioned before, part of the practice of taqiyya involves not attempting to learn or teach Isma‘ili theology without permission (i.e., taqiyya is practiced with others by concealing the Isma‘ili identity, but it is also practiced within the Isma‘ili community by not sharing theological knowledge without permission).

Reem was clearly aware of the recent social–political reforms. She emphasized that the recent reforms were first initiated by many educated scholars and intellectuals (or “enlightenments”, as Reem called them) who had significant roles in opening the door for conversations on various media platforms. She talked about King Abdullah’s work on establishing the National Dialogue Forum in 2003, which discusses religions and other related topics, as well as the recent reforms by the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman (known as MBS). Reem characterized the present time–space construction positively, where the recent reforms influenced the public discourse regarding Shi‘i (and other minority) communities.

When asked about her current practice of

taqiyya, Reem reported that she was still maintaining

taqiyya, even though she clearly distinguished between the chronotope of the difficult past and the chronotope of the present. The link between those opposing chronotopes provides her with a critical understanding of what

taqiyya means. For Reem, the past and present chronotopes are contrastive, yet connected, and therefore, reproducing

taqiyya in a different temporal and spatial configuration invokes safety and social inclusion.

taqiyya protected her (and the community) in the past and will protect her in the present and future and shape the possibility of coexisting with the larger community.

| 15 | Reem | our view of taqiyya is that do not show your knowledge to the others. |

| 16 | AA | hm |

| 17 | Reem | do not reveal your knowledge, ah for example (.) I mean protect yourself (.) these words “keep taqiyya” and “taqiyya is half of the religion” empowered me. I was comforting myself by saying “it is okay, I will practice taqiyya”, and “do not get involved in a conversation that might open a door to hell”. |

| 18 | AA | yes |

| 19 | Reem | I feel taqiyya protected me and my kids and allowed me to coexist with others in peace. |

| 20 | AA | hmm |

| 21 | Reem | [peace to a great extent] |

| 22 | AA | [hm::] |

| 23 | Reem | it protected me from the other or, better to say, from my fear. |

3.2. Interview 2: Ali

Ali was 66 years old at the time of our interview. He was born and raised in Najran City, then moved out to work in Al-Aḥsā in eastern Saudi Arabia for 18 years. Ali and Reem got married and settled down in the Hejaz region. They have been living there for over 30 years. In Hejaz, Ali got permission to study Isma‘ili theology until the moratorium in 2000. When the first author discussed the practice of taqiyya with Ali, he immediately claimed that he never practiced it. The first author then tried to create a common ground by narrating her past practices of concealment. The goal was to demonstrate that she was a legitimate member of the Isma‘ili community and to support any evaluative arguments about taqiyya during their discussion. Ali then shared that he started to conceal some of his Isma‘ili practices (but not his Isma‘ili identity) when he moved to Hejaz.

Similarly to Reem, Ali recognized the social–political changes in the present time space. In the conversation, he spoke positively about the new reforms and he quoted some of MBS’s public discourse about “moderate Islam”. The author then asked, “So we do not need to conceal our practices anymore?” He answered with a strong emphasis that all Isma‘ilis should maintain

taqiyya regardless of any social change.

| 1 | Ali | no, no, it’s not necessary, not necessary ((to reveal your Isma‘ili practices)) |

| 2 | AA | hm |

| 3 | Ali | we, in fact, cannot just reveal our fasting and Eid celebration (.) Saydina ((da‘i’s title)) emphasized that. |

Ali first explained that religious practices are private matters and that (“it is not necessary” (1)) to discuss them with non-Isma‘ilis. He then shifted his participant role from author to animator—invoking the words of the da‘i in order to demonstrate how the latter’s position aligns with his own. With this move, he accentuated the doctrinal and religious-epistemological significance of taqiyya, in contrast to the practical concerns that emerge from the other subjects’ interviews.

In discussing the present practice, the author talked about how people have recently engaged in intellectual conversations on online social media platforms about Isma‘ilism. The author illustrated the recent hashtag on Twitter (#Eid_Najran),

7 where people circulated video clips (posted by Isma‘ili youth on Snapchat public maps) of men celebrating Eid in Najran a day before the official state announcement of the holiday.

8 Very soon after the first video was posted, it went viral on Twitter, with some people condemning the Isma‘ili community, while others expressed their Eid wishes to them. Others inquired to the poster and commenters as to the reason for the differing dates. The Twitter discussion included conversations explaining that the Isma‘ili community follows a fixed tabular calendar established in the Fatimid period.

However, other Isma‘ilis, such as Ali, expressed disappointment that Isma‘ilis were violating

taqiyya by posting videos of Eid and engaging in conversations about Isma‘ili practices. During the discussion with Ali, the author aligned herself with those people who engaged in intellectual talk on social media platforms and Ali disagreed. He developed his argument by highlighting the importance of keeping esoteric knowledge from misinterpretation and public opinion.

| 4 | Ali | honestly (.) see some, ah, ignorant of other denominations |

| 5 | AA | hm |

| 6 | Ali | you know our religion is very deep and everything has esoteric interpretation |

| 7 | AA | yes |

| 8 | Ali | if they read ((Isma‘ilis’ esoteric interpretation)), they would perceive something strange (.) like fantasy, ah, and they are going to say “are those people insane? (.) what is this?” |

| 9 | AA | yeah |

| 10 | Ali | and so they would think we are a hereticized religion, so it is best not to discuss this↑ I am against anyone who discusses any topic about da‘i or da’wah ((the Isma‘ili mission)) on social media. |

For Ali, taqiyya is important for its function in protecting religious knowledge from profanation, and also for protecting the uninitiated from the dangerous (and potentially maddening) effects of exposure to esoteric knowledge. He explained that lapsing in the practice of taqiyya might lead those who lack spiritual qualifications (“ignorant of other denominations” (4)) to misinterpret the Isma‘ili esoteric knowledge and faith and accuse the Isma‘ili community of heresy (10). Ali’s discussion of the present time evokes the chronotope of meaning continuity that indexes the da‘i figure, piety, and the importance of protecting esoteric knowledge and the Isma‘ili community.

3.3. Interview 3: Bayan

Bayan was 29 years old when interviewed. She had lived most of her life in the Hejaz region with her parents, Reem and Ali, and moved to Najran City in 2018. Most of her social network in Hejaz consisted of non-Isma‘ilis. During that time, she practiced

taqiyya by concealing her tribe affiliation, Yam tribe, her town of origin, Najran City, and some of her Isma‘ili practices (e.g., praying and fasting) to mitigate the risk of losing her social relations in school as she explained below.

| 1 | Bayan | <ah:: maybe fear (.) I did not want to lose them ((her friends)), maybe fear (.) it was not about anything else> |

| 2 | AA | ahh |

The invocation of past space and time triggered Bayan’s memories of fearing social exclusion due to the public anti-Shi‘i discourse. She explained that she practiced taqiyya to maintain her social relations (“I did not want to lose them” (1)), and it was not based on religion or piety (“It was not about anything else” (2)).

Similar to her parents, Bayan talked positively about the new social reforms and how the new policies controlled hostile public discourse. It was surprising that Bayan’s discussion about the present reforms did not seem to influence her practice of

taqiyya. She stated that she sometimes conceals her Isma‘ili practices even though her non-Isma‘ili friends know that she is Isma‘ili and have become more accepting. She explained that her

taqiyya practice has become a habit and that sometimes it is not a conscious decision.

| 3 | Bayan | ah, a habit (.) it became a norm; I mean, we do not need to share ((religious practices with the other)). |

| 4 | AA | ahh |

| 5 | Bayan | I do not conceal because they told me to do so or because there is a reason (.) I conceal because this is how I have been raised. |

| 6 | AA | yeah |

| 7 | Bayan | it became a habit. |

Bayan’s discussion suggests that taqiyya has become tied to her everyday interactions with non-Isma‘ili through habitual practices and that her concealment (e.g., silence, avoiding certain conversations, crossing arms while praying) is not always intentional.

4. The Present: Transparency, Utility, and Contingency

The last two participants, Arwa and Aba‘d, do not align with the practice of taqiyya in the current space–time social condition. They explained that taqiyya was used in the past to preserve the community and the faith, but with the new sociopolitical reforms, it lost its utility. For Arwa and Aba‘d, taqiyya here and now is a tool for social isolation that hinders the community.

4.1. Interview 4: Arwa

Arwa was 29 years old and a graduate student in childhood education. She has lived her entire life in Najran City. As a teenager (mid-2000s), she was driven by the feeling of solidarity with the Isma‘ili community, especially after the political conflict that occurred in 2000. This political conflict made her realize that she had a role in protecting the community—“We have our practices and secrets”, Arwa said. She concealed her practices regarding fasting the first day of Ramadan and celebrating Eid, as well as avoiding topics about religion in general and Isma‘ili practices in particular.

Arwa talked about the present social changes positively, stating that the new social–political reforms have a big role in protecting religious minorities. We tried to elicit Arwa’s view regarding discussing Isma‘ilism with others, and she emphasized that online platforms such as Twitter allowed her to discuss topics that might be difficult in face-to-face conversations. She expressed her disappointment that although there are many online spaces to discuss various religious topics, there were none for Isma‘ilism because Isma‘ilis continue to practice

taqiyya, regardless of the social change. She referenced #Eid_Najran on Twitter and how some Isma‘ilis condemned the Isma‘ili community for discussing Isma‘ili practices on online platforms. In her talk regarding the #Eid_Najran Twitter discussion, she made a distinction between her past and present self, portraying herself as changing and gaining consciousness regarding practicing

taqiyya.

| 1 | Arwa | first time I saw it ((the hashtag)) it was shocking (.) but a small shock (.) I already raised my awareness ((that it is fine to talk about Isma‘ili practices)) (.) if I am still in my high school mentality £I would say£ “oh:: they exposed us” ((yelling)) ↑ you know |

| 2 | AA | ((laugh)) |

| 3 | Arwa | But I had good awareness. |

| 4 | AA | yes. |

| 5 | Arwa | that’s “oh we are here”↑ |

This excerpt is a good illustration of how Arwa organized her thoughts based on the opposition of past and present. She expressed her current feelings in relation to a specific past temporal and spatial flashpoint when she was committed to practicing taqiyya (“If I am still in my high school mentality, I would say ‘oh they exposed us’ (1)), but now with the social condition, she explained that there is a safe (online) space for Isma‘ilis: “Oh, we are here” (5).

In the next transcript, Arwa explained her explicit misalignment with

taqiyya in the present time–space and compared it to the past. She expressed that

taqiyya was a tool for protecting the faith and the community but had shifted to be a “veil” and “obstacle”, isolating the Isma‘ilis from the larger community and hindering the community’s success.

| 6 | Arwa | in the last 2 years, I like to open conversations about religion to explore people around me. |

| 7 | AA | yeah |

| 8 | Arwa | I put taqiyya on the side now. I feel it ((taqiyya)) is useless. |

| 9 | AA | why did you put it on the side? What is wrong with it? |

| 10 | Arwa | I feel it has become an obstacle. I think it is useless. It is just an obstacle = it is just a barrier from the light. |

| 11 | AA | How so? |

| 12 | Arwa | it restrains the ((Isma‘ili)) community, restrains me, restrains the Isma‘ili theology; that is to say, it’s a veil, a veil, you know, a veil from everything (.) from everyone= |

| 13 | Arwa | look, before I saw taqiyya as, I mean, something to protect us. ((4 lines omitted)) |

| 18 | Arwa | This is what I understood, and I agreed with this thing until the state protected us (.) Now we should talk. |

In the current time and space, Arwa no longer practices taqiyya because it isolates her from engaging in intellectual conversations with others (“it has become an obstacle. I think it is useless. It is just an obstacle; it is just a barrier from the light” (10)). She emphasized that with the recent social reforms, laws are meant to protect people; therefore, she explained that the old view of taqiyya no longer served that purpose.

4.2. Interview 5: Aba‘d

Aba‘d was 45 years old when interviewed. She has lived her entire life in Najran City and worked as a school administrator. Aba‘d stated that she was aware of

taqiyya and public anti-Shi‘i rhetoric, but she never practiced it even though she studied in schools with mostly Sunni students (much like her sister, Arwa), and that she was practicing Isma‘ilism. The first author asked Aba‘d about her perspective of

taqiyya in the present in view of the recent social reforms, and she developed her narrative by contrasting the past and present chronotopes.

| 1 | AA | Do you think taqiyya protects religion? |

| 2 | Aba‘d | protects religion? |

| 3 | AA | yes. |

| 4 | Aba‘d | honestly I mean yeah right it protected the religion |

| 5 | AA | hm |

| 6 | Aba‘d | it was (.) it was (.) but now I feel we have laws that protect everyone, either Isma‘ilis or non-Isma‘ilis. |

Similar to her sister Arwa, Aba‘d explained that taqiyya was essential, and “it protected the religion” (4), but the state laws substitute the need for taqiyya.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Some of our interlocutors argue that history has led Isma‘ili practices to be maladaptive in the face of Saudi Arabia’s rapidly changing social environment, while others hold fast to the notion of taqiyya as a timeless and essential component of the faith. Our participants’ narratives show how continuities and ruptures in the social conditions that motivated taqiyya have contributed to divergent understandings of the meaning and continued utility of the practice, and that these divergences seem to assume the shape of generational lines. Disagreements as to whether taqiyya plays the part of an outmoded impediment to community vitality or “half of the faith”, as one participant said, betray more fundamental departures from the question of the shared repertoire of meaning that grounds Isma‘ili social practice.

Our informants’ views of

taqiyya depended largely on how intimately they linked the concept to Isma‘ili ideologies of knowledge and knowledge circulation. The link, in turn, seemed to be largely contingent upon how much of the participant’s life was spent in the times before the social reforms and the moratorium on esoteric learning. While all the participants were expressly positive about the state-led social changes in Saudi Arabia, they differed greatly in opinion regarding the continued relevance of

taqiyya as a practice. We showed how the informants constructed the meaning of

taqiyya through the use of biographical and sociohistorical chronotopes anchored around the moratorium on Isma‘ili learning and the Saudi social reforms. For some informants, the meaning of

taqiyya was reshaped by their positive stance towards the new social reforms, while others maintained circulating

taqiyya as an essential and timeless practice, regardless of the social condition. The narratives of the first three informants, Reem, Ali, and Bayan, demonstrated that there was continuity in the meaning of

taqiyya. Reem and Bayan constructed their interpretations of

taqiyya within a biographical chronotope. For Reem,

taqiyya now, as with then, is essential for self-preservation and social inclusion, justified by the Isma‘ili maxim emanating both from the

da‘i and the Isma‘ili canon: “taqiyya is half of the religion”. For Reem,

taqiyya is perceived as a “system” of protection that prevents her from harm and criticism due to her lack of Isma‘ili esoteric knowledge.

9 Bayan likewise focused on social inclusion, expressing fear over losing friends because of her religious identity being revealed. Bayan additionally identified the practice of

taqiyya as persisting by force of habit, a feature of her upbringing. Ali constructed the meaning of

taqiyya within the chronotope of religious study. Ali was engaged in formal religious education prior to the moratorium in 2000, and his invocation of this time allowed him to emphasize the link between

taqiyya as a prudential practice and its theological significance. The conception of

taqiyya for these three informants demonstrated that

taqiyya is practiced even under “the apparent peace”, and is extended far beyond the social condition (

Layish 1985, p. 281).

By contrast, Arwa and Aba‘d expressed views of taqiyya being unnecessary and outdated. Both women constructed their meanings of taqiyya within the chronotope of the modern state. For Aba‘d, the function of the state has superseded the role once played by taqiyya. Openness and recognition—two of the hallmarks of the modern state—are inimical to the continued practice of taqiyya. In distinction to Bayan and Reem, whose narratives were autobiographical, Arwa and Aba‘d construct taqiyya in primarily sociological and political terms. In asserting that historically opposed groups should talk, Arwa assumes a positive stance toward stranger sociability and anonymity, hallmarks of liberal citizenship. In addition to the reforms, the internet seems to be a significant factor in upending the ideologies that served as the basis for taqiyya. Just as the case of the child at the festival related earlier in the paper can be read as a humorous emblem of the collision between new venues for stranger sociality and traditional expectations around divulgence, the circulation of Isma‘ili knowledge on the internet has a contradictory effect of at once providing the basis for wider and more democratic Isma‘ili self-recognition and cohesion, while at the same time, it critically undermines the religion’s most distinctive and longstanding ideologies of secrecy and circumscription. The novelty and relative anonymity afforded by social media like Twitter have permitted Isma‘ilis to bypass norms of information exchange without running overtly afoul of the community mores. Whereas most Isma‘ilis would, in face-to-face interaction, take pains to divert the prying eyes of outsiders from anything that would draw attention to religious practice, the internet has meant that phenomena of mass publicity like #Eid_Najran are virtually impossible to mitigate.

The internet’s ubiquity and the rapid demise of privacy over the course of the last few decades have likely been the impetus for an abrupt laxing of norms of Isma‘ili self-expression. For young people, taqiyya as it is traditionally understood seems outdated in a rapidly flattening world. In her interview, Arwa chose the very evocative metaphor of the veil to describe taqiyya as an impediment to modern life, explicitly making the comparison to a garment to be cast by the wayside in the spirit of progress. It is clear that, whatever course the present reforms ultimately take, Sulaymani Isma‘ilis have started inexorably down a path that will see them negotiate moral and epistemological questions that pertain to foundational aspects of the religion. Changes in Saudi society have been fast-moving for the past several years, and the social reforms have already proved to be an exogenous shock to the country’s Isma‘ili community at the same time (and to some degree for the very reason that) it has led to improved life conditions. We intend to continue watching the community with an eye toward how Isma‘ili consciousness reorients itself around changing social demands and new forms of publicity whose utilization only a generation ago would have been unthinkable.

The socialization of secrecy discussed in

Section 1.4 is a topic on which we could give only cursory treatment in the present paper. However, we believe that this is among the most fertile ground for continued investigation. The means by which Isma‘ili children are socialized into an Isma‘ili habitus includes very little in the way of explanation or explicit instruction. Through heavy censure on any discourse around domestic affairs (

asrār al-bayt), children in the community are disciplined to comport themselves with the sort of circumscription that will make them good stewards of religious secrets. Given this, it is less surprising that participants in this study—even those who grew up during the most harrowing time to be a religious minority—reported that they were unaware that they were even Isma‘ili until they were around twelve and began performing their religious obligations. It is only after this point that the secrecy that these participants had been practicing by force of habit was linked to its discursive, doctrinal referent. Beyond being merely an item of doctrine or a self-conscious tactic,

taqiyya does some of its work behind the backs of individuals, below the level of discursive consciousness. The parallels between everyday manifestations of

taqiyya and the negative theology of Isma‘ilism are striking. Aydogan Kars explains Isma‘ili theology as turning on a “double negation”. According to the first author, the following quote—written in an academic register—is surprisingly close in its language to lay theological discourse among the Saudi Isma‘ilis:

The first one negates the positive ground and relationality, and the second cancels all (positive and negative) discursivity in order to indicate the beyond of the relative oneness beyond creation. This “via negativa duplex” of the classical Ismā‘īlī theological tradition indicates the inapplicability and failure of any statement on God through its own performative self-cancellation. “Negating the divine attributes” means their inapplicability, rather than their negative applicability.

It’s not the case that the object of concealment to which

taqiyya (be it of the “prudential” or “non-prudential” variety, regarding the person’s religious association or some aspect of doctrine) applies is some proposition that the concealer is denying. In the cases of our participants’ recollections of childhood in the Isma‘ili community, in which they did not know they were Isma‘ili but they

knew what was acceptable and unacceptable to ask, and what sorts of information were appropriate to disclose and to whom, discursivity has been canceled in advance. Disclosure is not simply negated at the level of the proposition but rather “

via negativa duplex”. Children in Saudi’s Isma‘ili community were always already practicing concealment. Understood this way, taqiyya is evocative of

Mauss’s (

2015, p. 193) notion of the

total social fact: a supra-individual social project that influences and is influenced by various spheres. The present authors are in the preliminary stages of an ethnographic study of Isma‘ili family life that looks at the dialectic between Isma‘ili doctrine and ethical comportment. This ongoing work promises to be an important contribution to the literature on language socialization and language and identity.

10