Abstract

Bilinguals have been shown to adapt to syntactic innovations (i.e., structures that deviate from the standard grammar) either by producing such structures more or by processing them faster after repeated exposure. However, research on whether they adapt by increasing their acceptability ratings for innovations is limited. We consider this to be a crucial gap in the literature, since it could provide insights into how speakers adapt their perception for innovations that they might otherwise not adapt to in their production and/or processing. On this basis, the present study investigates overall acceptability and trial-by-trial acceptability (adaptation) for different types of innovations in Canadian French with grammatical structural equivalents in English. Structure type and individual differences in language experience (dominance, proficiency, exposure, etc.) are considered as factors that influence these processes, as previous research has shown that they play a role in the acceptability of innovations in bilinguals. For this purpose, we employed a timed acceptability judgment task (TAJT), where adult bilingual speakers of French and English in Canada were asked to rate innovative sentences in French and their standard (grammatical) counterparts as fast and spontaneously as possible. Both acceptability ratings (offline measure) and response times (RTs) (online measure) across trials were measured to test whether speakers show adaptation on both levels. Results revealed that innovations were rated lower and for most structure types slower than their standard counterparts, with the different types of innovations showing differences. Crucially, adaptation on a group level was reflected only in response times and not in acceptability ratings. On an individual level, though, some participants adapted their ratings, but not consistently across all innovation types. Moreover, ratings and RTs were influenced by individual language experience, with participants with a higher contact with French (higher French Score) being faster and less accepting of innovative sentences compared to participants with a lower contact with French.

1. Introduction

Speakers tend to quickly adapt to the properties of the language input they receive, including aspects such as the accent (Bradlow and Bent 2008) or the vocabulary of their interlocutors (Metzing and Brennan 2003), as well as the syntactic structures used (Bock 1986; Loebell and Bock 2003). Overall, adaptation is an important concept to investigate because it reflects how language changes over time as a result of interaction and communication between individual speakers or communities of speakers (Kaan and Chun 2018b).

For the purposes of this paper, we focus on syntactic adaptation, which is the adjustment of speakers to structures that they repeatedly encounter in their recent input. In the literature, it has been typically shown to occur in three different ways, namely in production, processing, and acceptability judgments. In production, speakers are more likely to use particular structures after they have been repeatedly exposed to them (Bock 1986; Loebell and Bock 2003; Hartsuiker and Pickering 2008; Kaan and Chun 2018a). In processing, they comprehend such structures easier and faster over time (Fine et al. 2013; Farmer et al. 2014; Kaan et al. 2019). As for acceptability judgments, they tend to rate these structures as gradually more acceptable over the course of a task (Luka and Barsalou 2005). Crucially, these aspects of adaptation do not necessarily coincide. For instance, speakers might adapt to a structure by processing it faster, but this does not necessarily lead to higher production or acceptability for this structure (cf. Regulez and Montrul 2023). Similarly, speakers might accept a structure more over time, but never or only rarely start producing it. It is, therefore, crucial to study adaptation from various perspectives in order to shed light on the different ways in which it can occur, as well as how these ways contribute to language change per se. In addition, it is also crucial to explore what syntactic structures speakers adapt to. To date, most studies have focused on structures that have alternative realizations with different frequencies (e.g., dative alternation in English in Bock (1986) and Kaan and Chun (2018a)) or on structures that elicit ambiguous readings (e.g., reduced relative clauses in Farmer et al. (2014); wh-clauses in Kaan et al. (2019)). However, in these cases, the structures always follow the syntactic rules of the respective language (i.e., are grammatical). Fewer studies have focused on structures that are innovative, in that they deviate from the standard grammar1 (e.g., The meal needs cooked; The soldier donates the church the money).

Evidence for adaptation to innovations are provided both in L1 and in L2 research. For instance, monolinguals have been shown to either use more innovations after repeated exposure (Ivanova et al. 2012) or process them faster (Kaschak and Glenberg 2004). L1 adaptation has also been found in the form of increasing acceptability ratings for such structures across experimental trials (Snyder 2000, 2022). Similarly, in bilinguals, adaptation to innovations has been reported in production (Carando 2015; Fernández et al. 2017; Kootstra and Şahin (2018) for bilingual adults; Hsin et al. (2013) and Van Dijk and Unsworth (2023) for bilingual children) and in processing (Phillips 2018; Ilen et al. 2023). However, in terms of acceptability, we are aware of only one study that tested how bilinguals change their acceptability ratings for particular innovations across trials (Do et al. 2016). We consider this to be a crucial gap in the literature, since adaptation in acceptability judgments can provide insights into the perception of innovations that (a) might otherwise not be produced after repeated exposure (Hopp and Jackson 2023), or be produced to a limited extent (Fernández et al. 2017), and (b) might be processed faster over time (Phillips 2018) but not become more acceptable. At the same time, it expands our understanding on how bilingual speakers rate such innovative structures in the first place, as it reveals whether overall acceptability patterns are a result of adaptation across trials or not (cf. Do et al. 2016).

To address this gap in the literature, we designed and implemented a timed acceptability judgment task (TAJT) with the aim to investigate the overall and across-trial acceptability (adaptation) of innovations in bilingual speakers. Unlike previous studies that tested adaptation in acceptability only via offline measures (ratings; see Snyder (2000, 2022) and Luka and Barsalou (2005) for L1; Do et al. (2016) for L2), this study employs both offline (ratings) and online measures (response times: RTs) to explore whether overall acceptability patterns and adaptation are reflected on both levels (cf. Kaschak and Glenberg 2004 for adaptation in reading times). We investigate this by testing different types of innovations in Canadian French with a grammatical structural equivalent in English, since previous studies have shown that different structures yield different results both in acceptability (cf. Montrul and Bowles 2009; Montrul et al. 2015) and in adaptation in acceptability (cf. Snyder (2000, 2022) for L1, and Do et al. (2016) for L2). Moreover, we explore the contribution of individual differences in these processes, as they have been found to be a determining factor for bilinguals in their acceptability of innovations (cf. Montrul and Bowles 2009; Kupisch 2012; Kupisch et al. 2014; Montrul et al. 2015; Higby 2016), but it is unclear whether and how they would influence adaptation in acceptability.

In the following sub-sections of the introduction, we provide a more thorough insight into the studies that have been raised here and that motivate this work. First, we present studies on adaptation to innovations in L1 and L2 research (Section 1.1), followed by studies on the bilingual acceptability of innovations that take other factors such as structure type and individual differences into account (Section 1.2).

1.1. Adaptation to Structural Innovations in L1 and L2 Research

Adaptation to innovative structural input has been investigated both in monolingual and in bilingual research by means of different methodologies. One of the earliest studies was conducted by Snyder (2000), who tested adaptation in the acceptability of various types of novel structures in monolingual English speakers. The results showed that acceptability ratings increased across experimental trials, but not for all structures tested. For example, ratings increased for whether-islands (Who does John wonder whether Mary likes?) and complex NP violations (Who does Mary believe the claim that John likes?), but not for left-branch violations (How many did John buy books?) and that-trace violations (Who does Mary think that likes John?). On this basis, Snyder formed the syntactic satiation hypothesis, according to which structures that have been initially judged as unacceptable tend to become more acceptable with multiple presentations. However, syntactic satiation is not an across-the-board-phenomenon, since only some structure types seem to undergo this process (Snyder 2022; also see Francom 2009; Zervakis and Mazuka 2013). Similar results on adaptation in acceptability upon repeated exposure (structural facilitation) were obtained by Luka and Barsalou (2005) for structures that were initially rated as moderately grammatical in English,2 but not as entirely novel (e.g., I miss having time to do anything/It’s uncertain he’ll arrive until after midnight).

Monolingual adaptation to innovations has been studied not only through the lens of acceptability, but also via structural priming. Structural priming shows how a recently encountered syntactic structure (prime) can unconsciously influence the production and/or comprehension of a subsequent syntactic structure of the same type (target). In Ivanova et al. (2012), L1 English speakers produced novel dative target sentences (The dancer donates the soldier the apple) after being exposed to similar prime sentences. However, the authors note that it is not clear whether this structure is fully novel or just dispreferred with specific verbs (cf. Zervakis and Mazuka 2013 and references therein). Other studies have focused on adaptation effects in online processing. Kaschak and Glenberg (2004), for instance, conducted a series of reading time tasks to assess the comprehension of a dialectal construction in English that was unfamiliar to their participants (The meal needs cooked). They showed that participants who were repeatedly exposed to the new structure learned to process it faster than participants who encountered it for the first time (see Fraundorf and Jaeger 2016 for a replication). According to the authors, this “can be seen as another demonstration of structural priming in language processing” (p. 464).

In bilingual research, studies on adaptation have mostly focused on innovative structures in one language with grammatical structural equivalents in the other language. Bilingual adaptation to such structures has so far been investigated primarily via cross-linguistic structural priming, whereby a fully grammatical prime in language A can facilitate the production or comprehension of a structurally equivalent innovative target in language B. A relevant study by Fernández et al. (2017) showed that Spanish–English bilingual speakers in New York City, US, and in Córdoba, Argentina, produced various types of Spanish innovations that bear English-like syntax (see Hsin et al. (2013) and Van Dijk and Unsworth (2023) for similar findings in bilingual children). For example, they produced reciprocal structures without the obligatory reflexive se (El turista y la novia (se) abrazaron ‘The tourist and the bride hugged’) and transitive structures without the obligatory accusative marker a (La científica saluda (a) la cantante ‘The scientist greets the singer’), in analogy to English. Crucially, they were more prone to do so after they were exposed to English primes compared to Spanish primes (Carando 2015), and the New York City bilinguals, overall, exhibited a higher number of innovative productions. In another study, Kootstra and Şahin (2018) found that Papiamento–Dutch bilingual speakers in two different environments (the Netherlands and Aruba) produced prepositional object datives in Papiamento (Obi ta duna e buki na Pieter ‘Obi gives a book to Pieter’), which is a highly dispreferred structure, after they heard structurally equivalent grammatical primes in Dutch.3 In line with Fernández et al. (2017), bilinguals in the Netherlands produced more Dutch-like innovations in Papiamento than bilinguals in Aruba.

Similar effects on bilingual adaptation have also been reported in comprehension priming. The findings of Phillips (2018) suggest that heritage speakers of Spanish in the US were facilitated by grammatical English primes in the online processing of structurally parallel novel Spanish targets containing a stranded preposition within the relative clause (Esta es la tienda que Gonzalo compró el pollo en ‘This is the store that Gonzalo bought the chicken in.’). In a more recent study, Ilen et al. (2023) obtained similar results in a self-paced reading task where early Turkish–German bilinguals read German target sentences with innovative analytic comparatives (mehr schön ‘more beautiful’) faster after grammatical Turkish prime sentences containing an analytic comparative structure (daha güzel ‘more beautiful’) than after Turkish prime sentences containing an indicative structure (güzel ‘beautiful’).

As for bilingual adaptation in acceptability, research is extremely limited. To our knowledge, there is only one study by Do et al. (2016), which tested late L2 speakers of English with Spanish as their L1 in an acceptability judgment task. Participants were asked to rate two different types of innovations in English involving subject–verb inversion (SVI) on a scale from 1—completely unacceptable to 5—completely acceptable. One type of innovation had a grammatical equivalent in Spanish (I wonder what will John buy at the store. sp. ‘Me pregunto qué comprará Juan en la tienda’), while the other type of innovation did not (What John will buy at the store? sp. ‘¿Qué Juan comprará en la tienda?’). The across-trial analysis showed that bilinguals adapted by improving their ratings only for the second innovative structure, but not for the first one. These results contradict previous findings on bilingual adaptation in production and processing for innovations with grammatical structural equivalents, since the structure with a grammatical equivalent did not show adaptation.

Overall, adaptation to innovations has been reported both for monolingual and for bilingual speakers in various studies employing different methodologies. Regarding adaptation in acceptability specifically, which is the focus of the present work, research suggests that L1 and L2 speakers tend to increase their acceptability ratings with repeated exposure across trials for specific types of innovations only, however (cf. Snyder 2000, 2022, and Do et al. 2016, respectively).

1.2. Acceptability of Structural Innovations in Bilinguals (No Adaptation)

In this section, we present a body of studies on the bilingual acceptability of innovations across different populations and language pairs, mostly in Romance–Germanic contact. These studies present results from overall acceptability rather than adaptation in acceptability across trials. Some of them test multiple structure types (e.g., Montrul and Bowles 2009; Montrul et al. 2015), while others focus on one structure type only (e.g., Kupisch 2012; Higby 2016). However, all of them consider individual differences as a factor that affects overall acceptability patterns in bilinguals.

In a written acceptability judgment task, Montrul and Bowles (2009) tested two types of structural innovations in Spanish that carry English syntax: (i) omission of the a-marker in Differential Object Marking (DOM) structures with animate objects (Maria conoce (a) mi hermana ‘Maria knows my sister’) and (ii) omission of the a-marker on the indirect object in ditransitive structures (Maria dio (a) Pedro un regalo ‘Maria gives Pedro a present/a present to Pedro’). They found that Spanish heritage speakers (HSs) with majority US English, overall, rated both DOM and ditransitive innovations significantly higher than their monolingual Spanish-speaking peers (see Montrul 2010 for DOM innovations in Spanish as a heritage language).4 It is worth noting that innovative DOMs were, overall, more acceptable than ditransitives, probably due to the fact that HSs produce them and, hence, are more familiar with them (cf. Carando 2015; Fernández et al. 2017). Moreover, proficiency was found to modulate performance in ditransitive innovations, with advanced HSs behaving monolingual-like as opposed to their low- and intermediate-proficiency peers (in line with Montrul (2010, 2019); Guijarro-Fuentes and Marinis (2007) for L2 and Higby (2016) for 2L1 and L2, contradicting Regulez and Montrul (2023)).

Innovative DOM structures were further tested in a later study with Spanish, Hindi, and Romanian as heritage languages in contact with US English (Montrul et al. 2015). An acceptability judgment task with grammatical and innovative sentences was performed in all three languages. Both bilinguals in the US (first-generation immigrants5 and HSs6) and monolingual speakers in the countries of origin (Mexico, India, Romania) took part. Across languages, the presence of the Spanish marker a, the Hindi suffix marker -ko, and the Romanian marker pe, respectively, was manipulated in DOM structures. Furthermore, the omission of these markers was tested in ditransitives for Spanish, Hindi, and Romanian (e.g., Spanish: Juan le dio (a) su padre dinero ‘Juan gave (to) his father money’), in dative experiencers for Spanish and Hindi (e.g., Hindi: John(-ko) paise ki aavashyaktaa hai ‘John needs money’) and in locatives for Romanian only (e.g., Cartea este (pe) masa ‘The book is on the table’). The results showed that HSs across groups were, overall, more accepting of these innovations than monolinguals, and for the Spanish group this was extended to the first-generation immigrants for innovative DOMs only. Similarly to Montrul and Bowles (2009), omissions in the DOM context were more acceptable than in the other structures. Moreover, for the Hindi and Romanian groups, the age of onset of bilingualism was found to be a significant predictor: (1) the first generation performed more monolingual-like and differed significantly from the HSs and (2) simultaneous Romanian HSs showed a higher acceptability of DOM omissions than sequential HSs, presumably due to longer exposure to English over the years (cf. Montrul 2010). Moreover, HSs across groups were shown to have significantly lower proficiency in their heritage language compared to the first-generation immigrants and the monolinguals, which might have contributed as well.

The age of onset of bilingualism was also investigated in Higby (2016), who compared early and late Spanish–English bilinguals7 in a task with one innovative structure, namely Spanish causatives carrying English syntax (Los maestros trotaron a los niños alrededor del patio ‘The teacher jogged the kids around the playground’). As one of the control conditions, they used structures that are entirely novel in both languages to establish whether possible higher ratings for causatives are attributed to the English influence.8 The results revealed that bilinguals rated causative innovations as somewhat acceptable, but still significantly higher than the entirely novel control items. As for the two bilingual groups, no significant differences were detected (in line with Montrul 2010; contradicts Montrul et al. 2015 for Hindi and Romanian). However, proficiency was shown to play an important role, as participants with higher Spanish proficiency rated causative innovations significantly lower (in line with Montrul and Bowles 2009; Montrul 2010).

Kupisch (2012) manipulated not only the age of onset but also language by testing German–Italian simultaneous bilinguals (2L1ers) who were either German- or Italian-dominant, as well as German L2 learners of Italian,9 in their acceptability of novel bare subject NPs in specific and generic contexts in Italian (*Donne guidano meglio ‘Women drive better’). Bare NPs in specific use are impossible in both Italian and German, while bare NPs in generic use are possible only in German. Participants were asked to rate these innovative sentences as good- or bad-sounding and correct the bad-sounding ones. It was found that both German-dominant 2L1ers and L2ers corrected bare NPs significantly less (i.e., accepted more) in generic contexts than in specific contexts, while Italian-dominant 2L1ers corrected regardless of context (in line with Montrul and Ionin 2010 for Spanish HSs). Moreover, German-dominant 2L1ers made significantly fewer corrections than both L2ers and Italian-dominant 2L1ers (contra Kupisch et al. 2014 for French–German bilinguals; cf. Kupisch 2014 for acceptability of innovative adjective placement in simultaneous German–Italian bilinguals); the two other groups also differed significantly. Kupisch points out that, unlike the age of onset, the length of language exposure seems to matter for the phenomenon tested: Italian-dominant 2L1ers who spent most of their life in Italy corrected across the board, and L2ers who had spent more years in Italy corrected more than German-dominant bilinguals who were, overall, less exposed to Italian (also see Serratrice et al. 2009 for the importance of exposure in bilinguals).

To summarize, the studies in this section highlight the importance of structure type and prior linguistic experience (age of acquisition, input, language exposure across the years, proficiency, etc.) in the acceptability of innovations. However, they do not consider recent linguistic experience, i.e., exposure during the task itself. In Montrul and Bowles (2009) and Montrul et al. (2015), for instance, innovative ditransitives were rated lower than DOMs, but still higher in HSs than in monolinguals. It is possible that this is a product of adaptation due to repeated exposure across trials. Moreover, the structures investigated in these studies are limited (one structure type or the omission of one marker across structure types in specific language pairs), so it is not clear which structures are potentially more dynamic, i.e., more susceptible to adaptation.

1.3. The Present Study

Based on the previous research presented in Section 1.1 and Section 1.2, bilinguals tend to adapt their production and processing for innovations in one language whose structural equivalent in the other language is grammatical. However, whether they adapt their acceptability judgments for such structures is still unclear. On this basis, we conducted a timed acceptability judgment task (TAJT) with the aim to explore overall acceptability and adaptation across trials for different types of innovations by means of two measures, namely acceptability ratings (offline) and response times (RTs) (online). To our knowledge, this is the first study to combine both measures in order to investigate adaptation to innovations in the context of acceptability, since previous studies have only employed acceptability ratings (cf. Snyder 2000, 2022; Luka and Barsalou 2005; Do et al. 2016).

As for the structures tested here, they are different types of innovations in Canadian French with grammatical structural equivalents in English. By including different structure types, we investigate whether this affects overall and trial-by-trial acceptability, as has been the case in previous studies on acceptability in other language pairs (e.g., Montrul and Bowles 2009; Montrul et al. 2015) and in studies on adaptation in acceptability (Snyder 2000, 2022 for L1, Do et al. 2016 for L2). The choice of Canadian French was mainly motivated by previous work testing L2 adaptation to innovations in environments where the two languages of interest are either in high or low contact (e.g., Spanish–English in New York City and Córdoba in Fernández et al. (2017), Papiamento–Dutch the Netherlands and Aruba in Kootstra and Şahin 2018). The findings show that bilinguals in high-contact situations adapted to innovations in their production more than bilinguals in low-contact situations. This creates the motivation from our side to study adaptation in another relatively high-contact situation that has not been explored from that perspective yet, namely French–English in Canada. It is worth mentioning, however, that, unlike adaptation, innovations in Canadian French have been studied extensively in the speech of bilingual Francophones (see Nicoladis 2002, 2003, 2006 for bilingual children, and Mougeon et al. 2005 for bilingual adolescents).

Alongside structure type, we are also interested in the effect of individual differences in the processes of acceptability and adaptation. Canada is an interesting setting to explore this due to the variability in the degree of contact between French and English across the country. According to the 2021 Canadian census, for instance, bilinguals in the provinces of Quebec and New Brunswick represent about 46% and 34% of the local population, respectively, while bilinguals in Ontario represent only about 10%.10 On this basis, we recruited bilinguals from different parts of Canada that varied in terms of their current and across-the-lifespan experience with the two languages.

1.3.1. Our Structures

We tested four types of constructions that have different argument structure realization across French and English (Montrul 2001; White 2003). The structures were selected based on (1) research on innovations that have emerged in varieties of Canadian French (Mougeon et al. 2005) and (2) research on innovations that have emerged in other language pairs with a Romance and a Germanic language in contact (see Fernández et al. 2017).

The first structure is ditransitives. In English, both prepositional object (PO) (1a) and double object (DO) (1b) constructions are allowed when indirect objects (recipients) are full noun phrases (NPs). In French, only POs are allowed in that case, and the indirect object is marked via the preposition à (2a-b).

| (1) | a. | The | manAGENT | gives | a | presentTHEME | to | the | womanRECIPIENT | (PO) |

| b. | The | manAGENT | gives | the | womanRECIPIENT | a | presentTHEME | (DO) |

| (2) | a. | L’ | hommeAGENT | donne | un | cadeauTHEME | à | la | femmeRECIPIENT | (PO canonical word order) |

| the | man | gives | a | present | to | the | woman | |||

| ‘The man gives a present to the woman.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | L’ | hommeAGENT | donne | à | la | femmeRECIPIENT | un | cadeauTHEME | (PO scrambled word order) | |

| the | man | gives | to | the | woman | a | present | |||

| ‘The man gives a present to the woman.’ | ||||||||||

For ditransitive innovations with two NP objects, our knowledge is very limited. Thibault (2022) briefly refers to DO-equivalent productions in some varieties of Sub-Saharan African French (montrer l’enfant instead of montrer à l’enfant ‘to show (to) the child’). In Canada, Mougeon et al. (2005) present a special case of innovative syntax in ditransitive structures with pronouns as indirect objects (instead of NPs). Typically, the pronoun would be placed before the verb (Elle nous dit ‘She tells us’), but they report evidence of post-verbal placement accompanied by the use of the dative marker à (Il dit à nous ‘She says to us’). Although Mougeon and colleagues refer to the case as an “intra-systemic variation” in language rather than contact-induced change (cf. Gadet and Jones 2008), Neumann-Holzschuh (2009) leans towards the latter.

Then, we examine monotransitive verbs that bear an unmarked direct object in English (3a–b), but is obligatorily marked in French via the prepositions à or de (4a–b).

| (3) | a. | The | boy | obeys | the | teacher. | |

| b. | The | girl | plays | the | guitar. | ||

| (4) | a. | Le | garçon | obéit | à | la | professeure. |

| the | boy | obeys | PREP | the | teacher | ||

| ‘The boy obeys the teacher.’ | |||||||

| b. | La | fille | joue | de | la | guitare. | |

| the | girl | plays | PREP | the | guitar | ||

| ‘The girl plays the guitar.’ | |||||||

Mougeon et al. report instances of the omission of à with the verb jouer (to play sports) in the speech of French-speaking adolescents in Ontario (i.e., Il joue le hockey instead of Il joue au hockey). Interestingly, this structure has not been found in the speech of Francophones in Quebec. Note that this novel structure is not an exact replication of the English syntax, which would be Il joue hockey ‘He plays hockey’. However, in this study, we include this structure as it occurs in the spontaneous speech of Ontario bilinguals.

| (5) | The | two | friends | hug. | ||

| (6) | Les | deux | amis | s’ | embrassent | |

| the | two | friends | REFL | hug | ||

| ‘The two friends hug.’ | ||||||

The third phenomenon we test is reciprocal structures. In English, reciprocity is typically expressed via each other. However, some verbs convey reciprocity in active form without any complementation, like hug, kiss, meet, etc. (5). In French, the reflexive se is required in this context (6).

For reciprocals, we did not find any studies on the omission of the reflexive se in Canadian French (or any other variety of French). However, it is a common omission in the Spanish of Spanish–English bilinguals in the US (Fernández et al. 2017). We included this structure to test whether this applies across contact contexts for languages that behave similarly, like Spanish and French.

The fourth structure is object clitics in finite clauses. In English, object pronouns and clitics are placed after the verb (7). In French, there is a distinction between atonic and tonic pronouns, whereby the former are typically placed pre-verbally and the latter post-verbally. Here, we focus on the pre-verbal ones in the context of declarative finite sentences (8).

| (7) | He | puts | them | on | the | table. | |

| (8) | Il | les | met | sur | la | table. | |

| he | them | puts | on | the | table | ||

| ‘He puts them on the table.’ | |||||||

According to Mougeon et al. (2005), there is no evidence of post-verbal clitic placement in Ontario or Quebec French. However, such instances have been spotted in the speech of some speakers of French in Massachusetts, US (cf. Fox 2004 as cited in Mougeon et al. 2005).

1.3.2. Research Questions and Hypotheses

The research questions and hypotheses of the study are the following.

Research Question 1: How do Canadian bilingual speakers of French and English accept structural innovations in French compared to the standard (grammatical) variants? Are acceptability patterns different for the different types of innovations?

Hypothesis 1.

Overall, we expect structural innovations to yield lower ratings and slower RTs than the standard variants (see studies in Section 1.2). On the basis of previous studies that found differences in the acceptability of different structures in other languages (Montrul and Bowles 2009; Montrul et al. 2015), we also expect to find differences among the different structure types in acceptability ratings for the innovations. In Mougeon et al. (2005), most French innovations that were attested in the speech of Canadian bilinguals involved either the addition or omission of prepositions in the argument structure of verbs, while the only innovation that involved inversion was not found in corpora. On this basis, we hypothesize that bilinguals might be more prone to omit (or add) than to invert when they produce an innovation. If familiarity with an innovation in the input indeed yields higher acceptability ratings (cf. Montrul and Bowles 2009), then we expect that ditransitive, monotransitive, and reciprocal innovations (omissions) might be rated closer to—but still lower than—the standard variant compared to object clitics (inversion).

Research Question 2: Do bilingual speakers show adaptation to innovations over the course of the task? Is adaptation different for the different types of innovations?

Hypothesis 2.

We assume that adaptation is expressed both in ratings and in RTs. If participants accept innovative sentences from the beginning of the task, no or little further adaptation is expected. However, if they provide relatively low ratings initially, adaptation is expected (cf. Snyder 2000, 2022). Upon the absence of an effect in ratings, an effect in RTs is predicted (cf. Kaschak and Glenberg 2004). Moreover, we expect to find differences between the different innovation types, with participants adapting more to ditransitive, monotransitive, and reciprocal innovations compared to object clitics due to potentially less familiarity with the latter (see RQ1).

Research Question 3: What is the role of individual differences (age of acquisition (AoA) of French and English, amount of current exposure and use of each language, proficiency) in the acceptability of and adaptation to innovations?

Hypothesis 3.

A later AoA of French and/or reduced French exposure and use (Montrul et al. 2015; Kupisch 2012) and/or lower proficiency in French (Montrul and Bowles 2009) are expected to lead to the higher and faster acceptability of innovations, both overall and across trials (adaptation).

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

Recruitment took place primarily via Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/, accessed on 31 July 2023), where we set specific prescreening criteria to recruit bilingual adult speakers of French and English. Seven participants were recruited through personal contacts and received the study link via email. We ended up with a heterogeneous sample both in terms of acquisition patterns and current language experience. Information on the linguistic background of participants was gathered via the LEAP-Q (Marian et al. 2007).

Initially, 68 bilingual speakers took part in the study. We excluded six participants due to early acquisition of languages other than French and English, including Spanish, Portuguese, Kabyle (Berber language in Algeria), Arabic, Japanese, and Haitian Creole. The final sample consisted of 62 bilingual speakers of French and English (mean age = 26.8, SD = 4.2) born, raised, and living in Canada at the time of testing. In total, 26 of the 62 participants (41.9%) were early bilinguals of French and English (started acquiring both languages before the age of 5): 2 simultaneous (from birth), 7 sequential French–English (French from birth; mean AoAEnglish = 3.9, SD = 1.2), and 17 sequential English–French (English from birth; mean AoAFrench = 4.3, SD = 0.7). A total of 19 of the 62 (30.7%) were late11 L1 English–L2 French bilinguals (English from birth; mean AoAFrench = 9.8, SD = 5.5). Finally, the sample also contained 17 (27.4%) late L1 French–L2 English bilinguals (French from birth; mean AoAEnglish = 8.2, SD = 1.9). Twenty-one participants (33.9%) reported having a third language besides English and French including Spanish, Italian, Romanian, German, Swedish, and Japanese. For all of them, it was acquired after the age of 10 (Mean AoA = 16.1, SD = 4.2) and was not a family language. Their self-reported proficiency was, overall, low (mean = 3.6 on a 10-point scale, SD = 0.7).

On average, participants reported using their L1 81.9% of the time (SD = 22.1), and their L2 17.5% of the time (SD = 22.8). For simultaneous bilinguals, L1 and L2 were determined based on the order of report in the LEAP-Q as Language 1 and Language 2, respectively. Participants with an L3 reported using it 1.6% of the time daily (SD = 5.7). All participants took the LexTALE proficiency test both for French (Brysbaert 2013) and for English (Lemhöfer and Broersma 2012). The mean scores per bilingual group are presented in Table 1. No participant was excluded based on their performance in the tests.

Table 1.

Mean percentage of correct responses in French and English LexTALE per bilingual group. The distinction between early and late bilinguals is followed here for descriptive purposes and will not be retained in the analysis.

Moreover, 3 participants reported having ADHD. Since we were not certain whether ADHD could be of relevance for our study, we ran separate analyses with and without these participants. The results were, overall, similar (see analyses on OSF), so we decided to include them.

French Score: Canadian Bilinguals on a Continuum of Contact with French

In Table 1, we split our bilinguals into three distinct groups according to their AoA of French and English. However, grouping based on this one variable only results in a less nuanced description of their individual linguistic experience (cf. Kupisch 2012), especially given the diversity in our sample: these bilinguals live in a relatively high-contact environment (Canada), but the current amount of individual contact with each language varies a lot regardless of AoA. In our study, we expect that both AoA (Montrul et al. 2015) and current individual exposure and use of the two languages will shape participants’ performance (Serratrice et al. 2009; Kupisch 2012). Moreover, proficiency (assessed through LexTALE) is another variable that is likely to play a role, since it could—at least to some extent—predict familiarity with the structures we tested (Montrul and Bowles 2009; Montrul 2010, 2019).

Since we could not use all these variables in the analysis due to their high correlation, we merged them into one composite individual variable named French Score. To decide whether this was possible in the first place, we performed a factor analysis via the factanal() function in the nFactors package (Raiche and Magis 2022) in RStudio (R Core Team 2023) using the following individual measures: AoA (difference between French and English AoA as reported in LEAP-Q), amount of current French exposure (proportion, reported as percentage in LEAP-Q), amount of current French use (proportion, reported as percentage in LEAP-Q), and French proficiency score (percentage score in LexTALE). The output of the function provided us with (1) the information that these variables can indeed be merged in a single variable and (2) the weights that correspond to each variable when merging them. The outcome variable is a score corresponding to each individual participant and is interpreted as follows: the higher the French Score, the higher the contact with French.

2.2. Items

Participants performed a timed acceptability judgment task (TAJT) where they rated French grammatical and innovative sentences of various structure types. They were instructed to provide a rating as fast and intuitively as possible based on how natural the sentences sounded to them on a scale from 1 ‘completely unnatural’ to 5 ‘completely natural’. It was specified that a sentence is considered ‘natural’ when they would expect to hear it in their environment or use it themselves.12

Stimuli sentences were created and matched for length (number of words) across structure types. For each structure, six verbs were selected. For ditransitives, we used donner ‘to give’, montrer ‘to show’, lancer ‘to throw’, vendre ‘to sell’, envoyer ‘to send’, and apporter ‘to bring’. In total, 48 sentences were created and distributed across four conditions, resulting in 12 items per condition (Table 2).

Table 2.

Set of conditions for ditransitive items with an example stimulus.

Across conditions, the form and the syntactic position of the indirect object (femme ‘woman’) were manipulated. In the two standard (grammatical) conditions, it was expressed as an à-marked prepositional object (PO) that either followed the direct object (cadeau ‘present’) in canonical word order (PO_Can) or preceded the direct object in scrambled word order (PO_Scr). In the two innovative conditions, the dative marker à was omitted and the indirect object either preceded the direct object as an analogy to the English DO (DO_Engl) or followed it (DO_Nov), resulting in a structure that was novel in both languages. With this set of conditions, we were able to create a structural continuum across French and English: PO_Can is grammatical in both languages, PO_Scr is grammatical only in French, DO_Engl is innovative only in French, and DO_Nov is innovative in both languages (cf. Kupisch 2012; Higby 2016 and Do et al. 2016 for similar manipulation).

For the monotransitive stimuli, the following six verbs were used: jouer à ‘to play sports/game’, assister à ‘to attend something’, ressembler à ‘to resemble someone/something’, obéir à ‘to obey someone/something’, jouer de ‘to play an instrument’, and se tromper de ‘to get something wrong’. These are all verbs that obligatorily mark their direct object in French, but not in English. For reciprocals, we selected s’embrasser ‘to kiss/hug’, se rencontrer ‘to meet’, s’entendre ‘to get along’, se disputer ‘to argue’, se parler ‘to talk’, and s’écrire ‘to text’. These are all verbs that require a reciprocal in French but not in English. Finally, for the object clitic sentences, we used the transitive verbs suivre ‘to follow’, regarder ‘to watch’, acheter ‘to buy’, mettre ‘to put’, trouver ‘to find’, and écouter ‘to listen’. These structures require the (clitic) pronoun to precede the verb in French, but to follow the verb in English. Twenty-four items were constructed for each of these three structures and, unlike ditransitives, distributed across two conditions only, a standard/grammatical (Standard_Fr) and an innovative (Innov_Engl) one (Table 3). In the Innov_Engl condition, the prepositions à/de were omitted for monotransitives, the reflexive se was omitted for reciprocals, and the clitic was placed post-verbally for object clitics.

Table 3.

Set of conditions for monotransitive, reciprocal, and object clitic items with an example stimulus for each.

2.3. Design

We constructed four different presentation lists across which the ditransitive items were distributed on the basis of a Latin square design. Each list consisted of 48 ditransitive sentences, 12 from each of the four conditions. The other structures were also distributed across two lists on the basis of a Latin square design. Each of the ditransitive lists was combined with each of the lists for the other structures, resulting in a total of eight presentation lists (4 × 2). Participants were assigned randomly to one of the eight lists that consisted of 120 items in total (48 ditransitives, 24 transitives, 24 reciprocals, 24 object clitics), 50% of which were innovations. We did not use any filler sentences due to the large number of test sentences and to the fact that the study was conducted online. Items corresponding to one structure could be taken as fillers for another structure (cf. Kupisch et al. 2014).

2.4. Procedure

This study was implemented in Gorilla (Anwyl-Irvine et al. 2020). At the beginning, participants were asked to choose the language they felt most comfortable to receive task instructions in. They first completed the TAJT, followed by the LexTALE test for English and French, and, finally, the LEAP-Q that was provided either in Canadian English or in Canadian French (based on the preferred instruction language). For the LexTALE tests, we used the instructions provided in Lemhöfer and Broersma (2012). The total duration was approximately 30 min. At the end of the study, Prolific participants were redirected to the platform for their compensation. The external participants contacted the researcher with a completion code to pursue their Amazon voucher.

2.5. Predictions

The standard (grammatical) conditions PO_Can (PO with canonical word order) in ditransitives and Standard_Fr in monotransitives, reciprocals, and object clitics are predicted to yield the highest ratings (4–5) and the fastest RTs across all participants. Due to ceiling performance, no further adaptation in ratings is expected. However, RTs are predicted to decrease across trials because repeated exposure throughout the task might lead to adaptation.

The innovative conditions DO_Engl in ditransitives and Innov_Engl in monotransitives, reciprocals, and object clitics are predicted to yield, overall, lower ratings (1–3) and slower RTs compared to their standard counterparts. However, acceptability is expected to be modulated by individual differences in language experience, whereby higher French Scores in participants (i.e., higher contact with French) should result in lower ratings and faster RTs compared to lower French Scores. Moreover, acceptability in these conditions might be modulated by Trial Number: an Increasing Trial Number, i.e., increasing exposure to innovations, is expected to lead to increasing ratings and decreasing RTs. This effect is expected to be stronger for participants with a lower French Score, since their tolerance towards innovations in French (either due to lower French experience or due to CLI from English) should be higher.

For the two conditions that are specific to ditransitives, namely PO_Scr (PO with scrambled word order) and DO_Nov (DO with novel word order), we make the following predictions: PO_Scr is a condition that behaves differently cross-linguistically but, unlike DO_Engl, is fully grammatical here. We expect, overall, high ratings and fast RTs, but still slightly lower (3–4) and slower compared to the PO_Can condition (PO with canonical word order) due to the word order that might be less preferred out of context; some adaptation in ratings and RTs is also expected. However, since this structure is highly dispreferred and rare in English, it is expected that participants with lower French Scores will give lower ratings—even below 3—and will show slower RTs. Finally, the DO_Nov condition is predicted to yield the lowest ratings (1–2) across participants regardless of their French Score, but also low RTs (fast rejection). Adaptation is not expected on the basis of ratings. However, RTs are predicted to become even lower across trials due to potential facilitation from repeated exposure.

2.6. Data Preprocessing and Analysis

Ratings (ordered dependent variable) were analyzed via the clmm() function for cumulative link mixed-effects models in the ordinal package (Christensen 2023) in RStudio (R Core Team 2023). The four structures were analyzed via four separate models, one for each structure. As fixed effects in the model for ditransitives, we included Condition (factor with four levels: PO_Can, PO_Scr, DO_Engl, DO_Nov), French Score (continuous, scaled, and centered), Trial Number (continuous, scaled, and centered), and all their interactions. As fixed effects in the models for monotransitives, reciprocals, and object clitics, we included Condition (factor with two levels: Standard_Fr, Innov_Engl), French Score (continuous, scaled, and centered), Trial Number (continuous, scaled, and centered), and all their interactions.13 Condition was treatment-coded with PO_Can and Standard_Fr, respectively, as reference levels. Pairwise comparisons between all condition levels in the ditransitives model were obtained via the emmeans() function in the emmeans package (Lenth et al. 2018) and p-values were adjusted using the Holm method. As random effects, Participant and Item were implemented in a maximal structure that converged (Barr et al. 2013) and was gradually simplified, whereby the model with the lowest AIC was chosen as the final model. The fixed effects’ structure was not simplified because we are interested in all interactions involved.

Response times (RTs) (continuous dependent variable) were analyzed via the lmer() function for linear mixed-effects models in the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in RStudio. In our study, RT measures response latency, i.e., the total time in milliseconds from the presentation of a stimulus to when a response (rating) is submitted by the participant. Prior to the analysis, raw RTs were trimmed in two steps: (1) extreme values as indicated in the Q-Q plot were removed and (2) outliers +1 SD away from the overall mean per structure were removed. We decided to use this threshold due to the large SD across structures after removing the extreme values. We did not apply trimming for −1SD, as this would be a negative threshold. The trimming process resulted in removing approx. 5% of the initial/untrimmed dataset that included all structures. In order to reduce skewness, RTs were log-transformed for the analysis (Baayen and Milin 2010). We used the same fixed effects structure as in the ordinal analyses, and the same procedures regarding simplification on the random effects structure and model selection were followed.

3. Results

The anonymized data, R scripts, and full model outputs in HTML format are freely available at the Open Science Framework (OSF) under the following link (also provided at the end of the manuscript):

3.1. Ditransitives

3.1.1. Ratings

Ratings in ditransitive items were analyzed using the ordinal model in (1):

- (1)

- Rating ~ Condition + French Score + Trial Number + Condition: French Score + Condition: Trial Number + French Score: Trial Number + Condition: French Score: Trial Number + (1 + Condition + Trial Number | Participant) + (1 | Item)

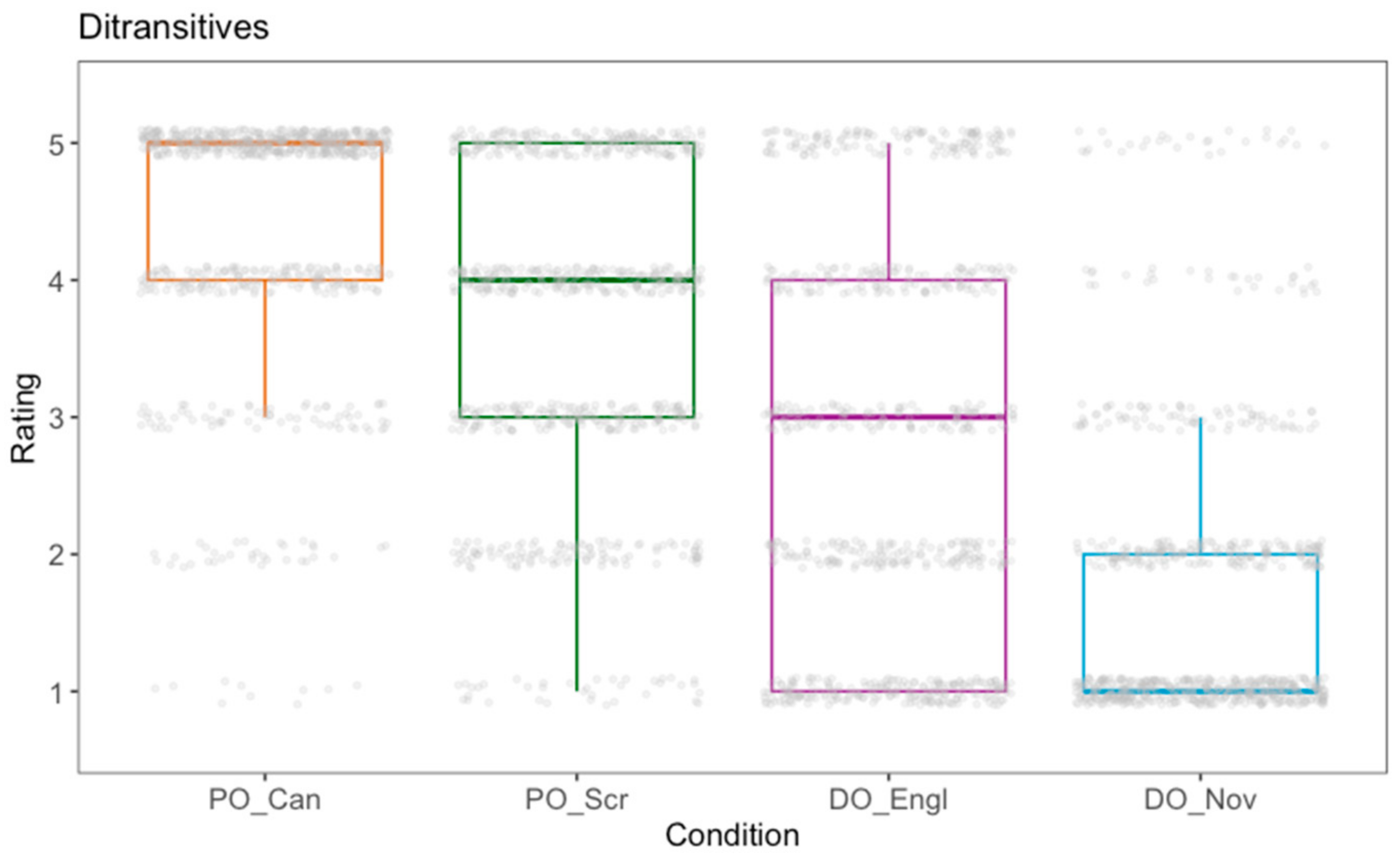

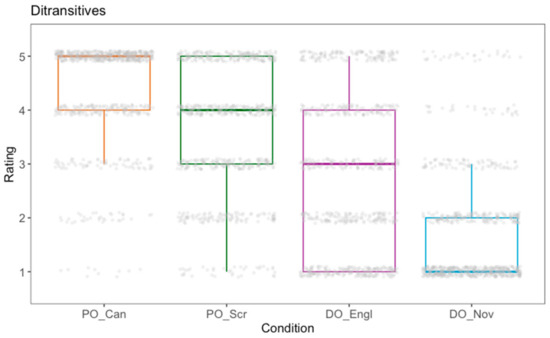

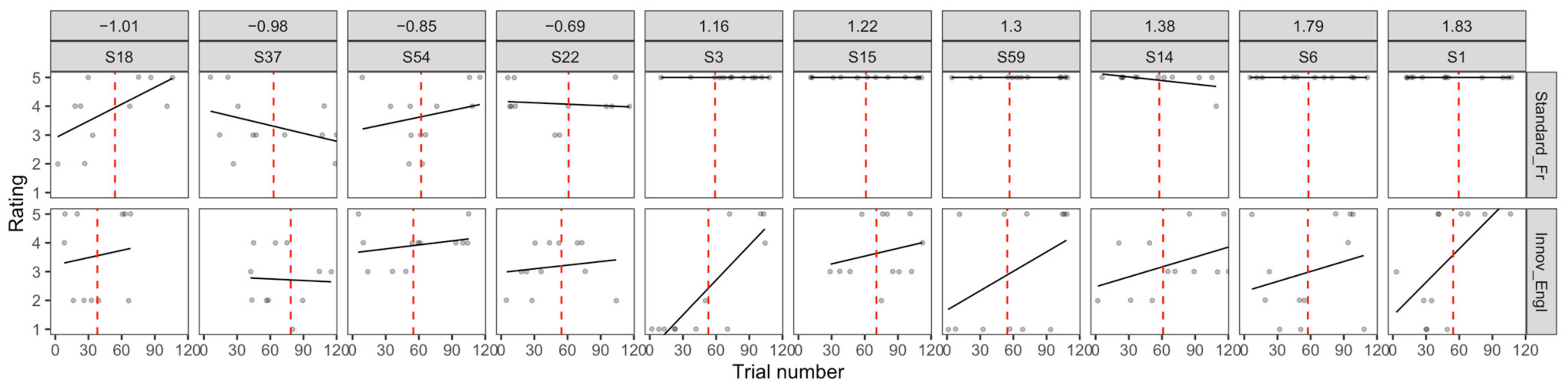

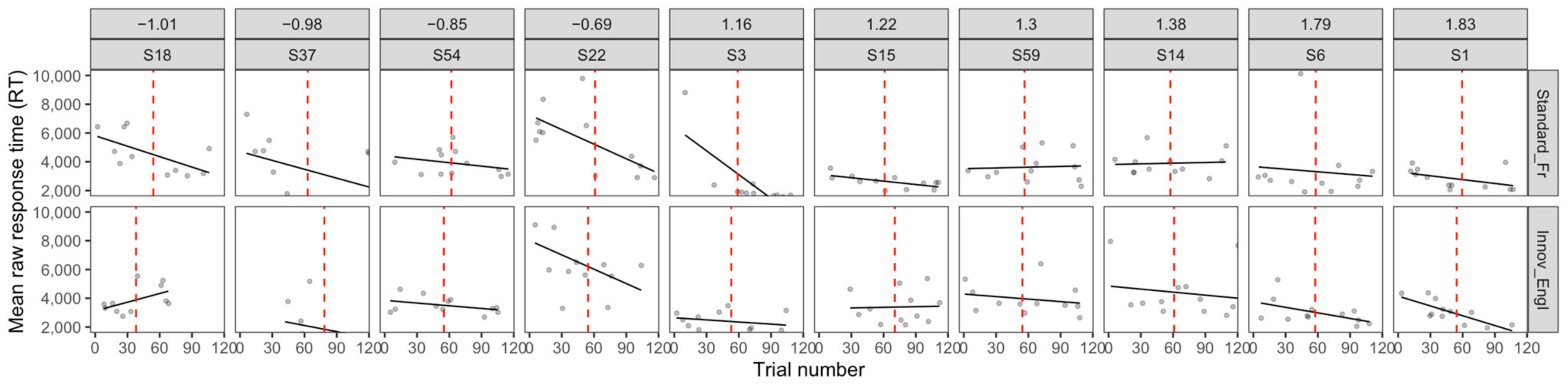

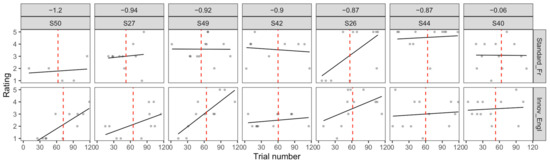

Figure 1 shows the distribution of individual ratings across the four conditions. Our analysis revealed that PO_Can sentences (L’homme donne un cadeau á la femme ‘The man gives a present to the woman’), overall, yielded significantly higher ratings than PO_Scr sentences (L’homme donne á la femme un cadeau ‘The man gives to the woman a present’) (β = −2.09, SE = 0.22, z = −9.72, padj < 0.0001), DO_Engl sentences (L’homme donne la femme un cadeau ‘The man gives the woman a present’) (β = −4.11, SE = 0.34, z = −12.08, padj < 0.0001), and DO_Nov sentences (L’homme donne un cadeau la femme ‘The man gives a present the woman’) (β = −6.67, SE = 0.39, z = −16.7, padj < 0.0001). As for the rest of the pairwise comparisons,14 it was found that participants rated the PO_Scr condition significantly higher than both innovations: DO_Engl (β = −2.02, SE = 0.29, z = −6.97, padj < 0.0001) and DO_Nov (β = −4.59, SE = 0.37, z = −12.31, padj < 0.0001). Crucially, DO_Engl sentences were accepted more than DO_Nov sentences (β = −2.56, SE = 0.35, z = −7.38, padj < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of individual ratings (gray dots) within the four conditions. The bold horizontal line in each box is the median rating per condition.

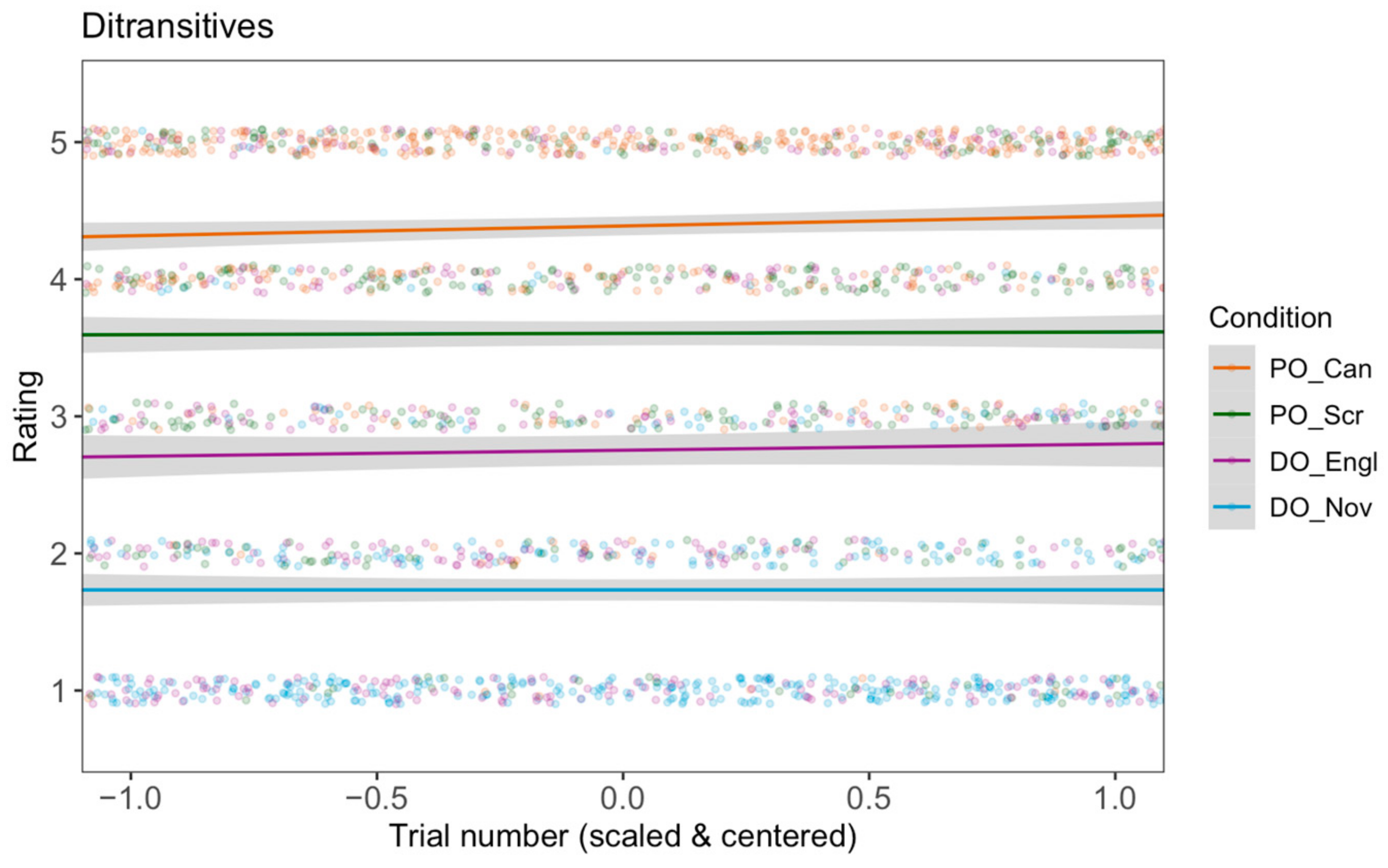

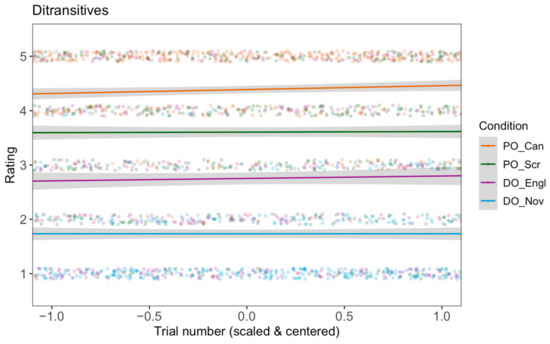

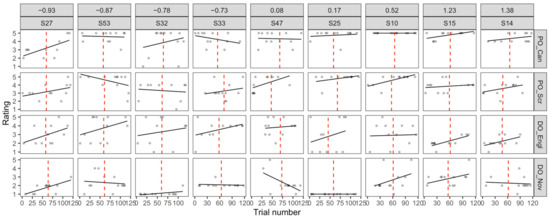

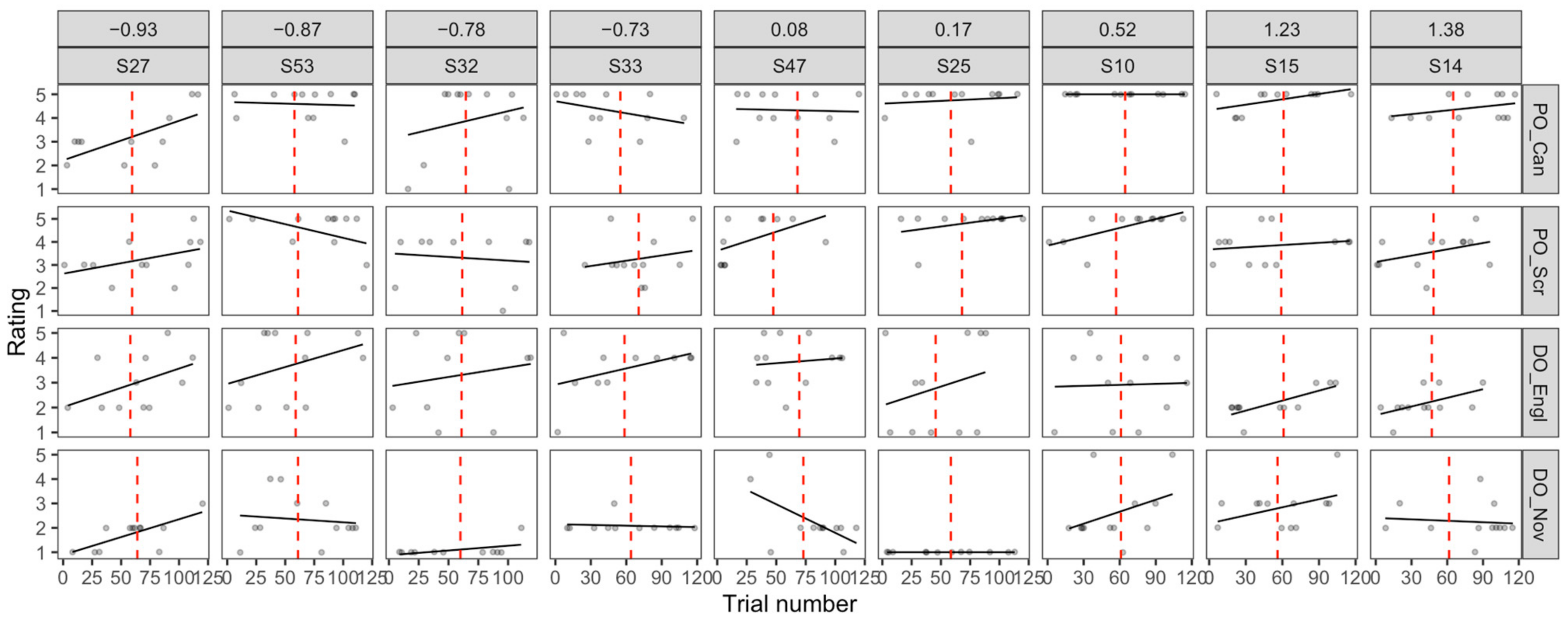

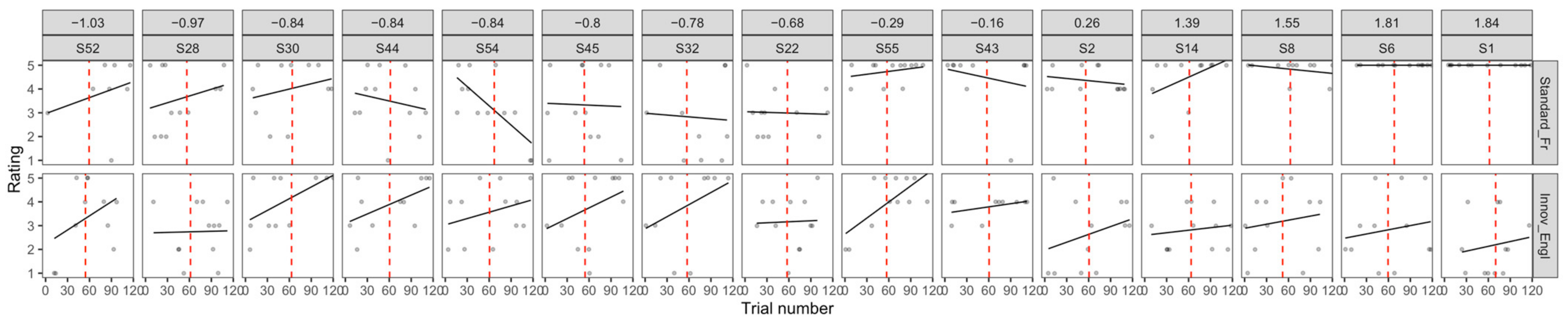

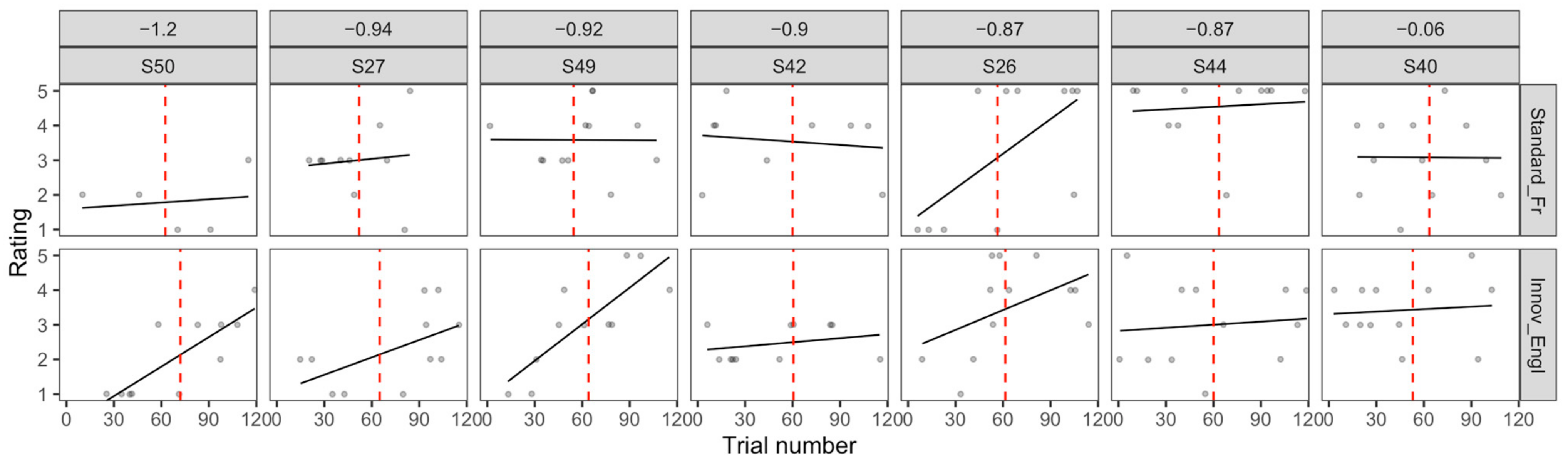

An increasing Trial Number (Figure 2) was found to significantly increase ratings in the PO_Can condition (β = 0.26, SE = 0.11, z = 2.29, p = 0.02). The interactions between Trial Number and Condition showed that, compared to PO_Can, the effect of the Trial Number was not significantly different in the conditions PO_Scr (β = −0.15, SE = 0.12, z = −1.22, p = 0.2), DO_Engl (β = −0.19, SE = 0.14, z = −1.42, p = 0.2), or DO_Nov (β = −0.22, SE = 0.14, z = −1.52, p = 0.1).

Figure 2.

Effect of Trial Number on rating per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the four conditions.

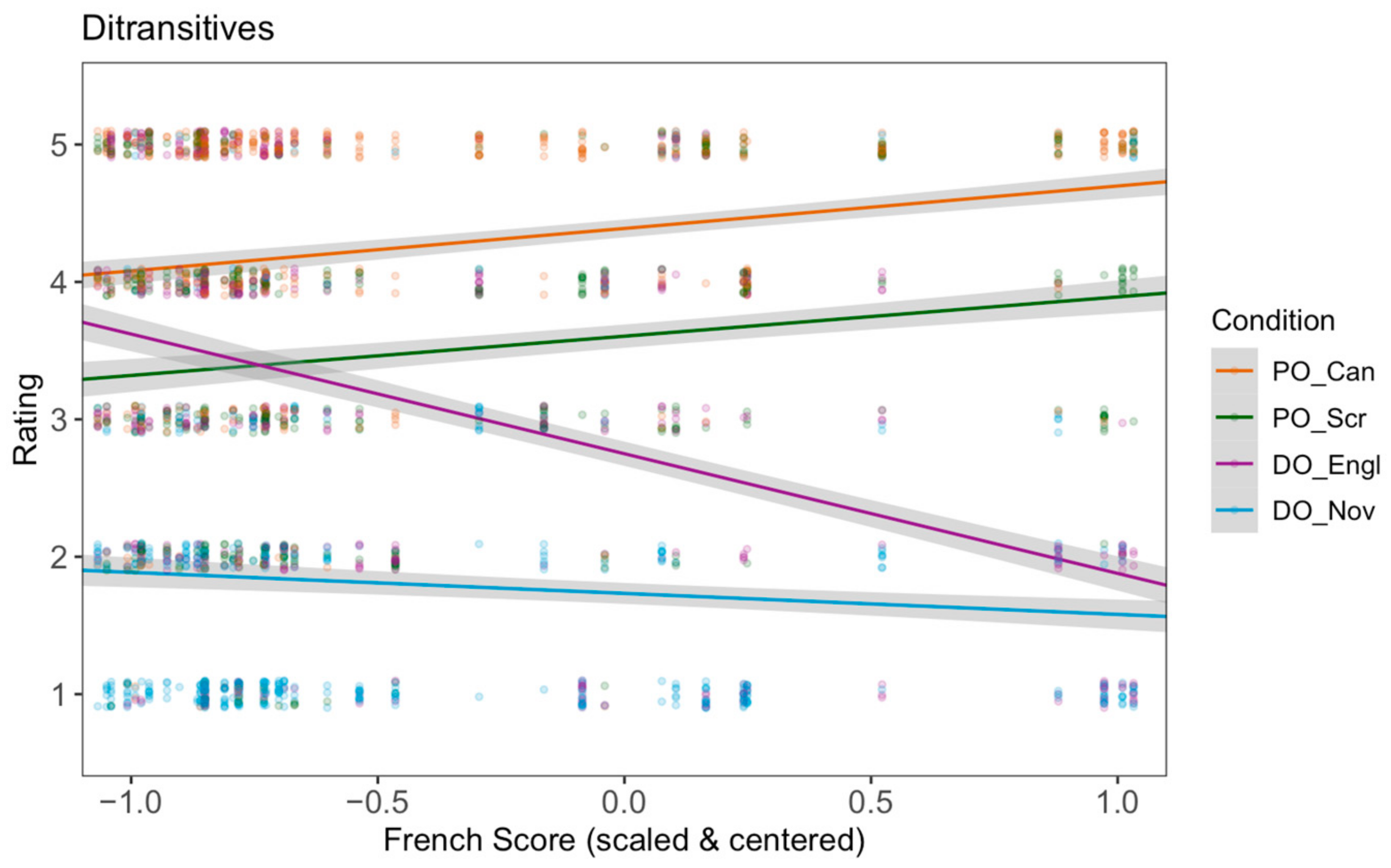

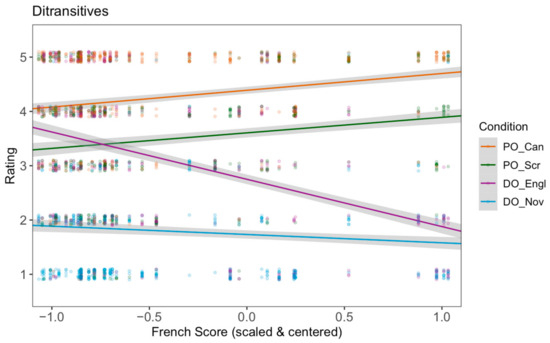

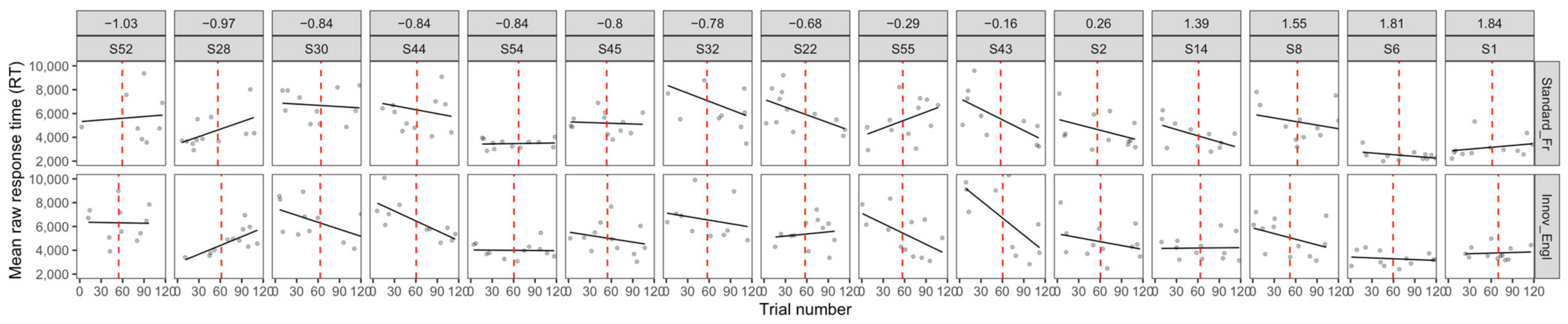

The contribution of French Score on ratings per condition is depicted in Figure 3. In the PO_Can condition, increasing French Score in participants led to a significant increase in ratings (β = 1.17, SE = 0.2, z = 5.73, p < 0.0001). The predictor’s interactions with Condition indicated that, compared to PO_Can, the effect of French Score was significantly more negative for PO_Scr sentences (β = −0.56, SE = 0.22, z = −2.56, p = 0.01), DO_Engl sentences (β = −3.29, SE = 0.35, z = −9.51, p < 0.0001), and DO_Nov sentences (β = −1.83, SE = 0.38, z = −4.78, p < 0.0001). Because these interactions were significant, we releveled the model to obtain the exact effect of French Score in the other conditions. P-values were adjusted with the Holm method via the p.adjust() function to avoid an increase in Type I error due to multiple releveling. The results show that increasing French Score in participants led to a significant increase in acceptance for the PO_Scr items (β = 0.61, SE = 0.2, z = 3.03, padj = 0.005). Crucially, it was less strong compared to the PO_Can condition. For DO_Engl items, the higher the French Score was, the lower the acceptability ratings were (β = −2.13, SE = 0.29, z = −7.13, padj < 0.0001); the same tendency was found for the DO_Nov items but to a lesser degree (β = −0.67, SE = 0.32, z = −2.1, padj = 0.04).

Figure 3.

Effect of French Score on rating per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the four conditions.

In addition, no significant interaction was found between French Score and Trial Number for PO_Can sentences (β = 0.08, SE = 0.12, z = 0.62, p = 0.5), showing that ratings remained stable across trials in this condition regardless of participants’ French Score. Compared to PO_Can, the effect of this interaction was not found to be significantly different in the conditions PO_Scr (β = −0.18, SE = 0.13, z = −1.38, p = 0.2), DO_Engl (β = −0.1, SE = 0.15, z = −0.68, p = 0.5), and DO_Nov (β = −0.005, SE = 0.15, z = −0.04, p = 0.9).

3.1.2. Response Times

Log-transformed response times (RTs) in ditransitive items were analyzed using the linear mixed model in (2):

- (2)

- Log RT ~ Condition + French Score + Trial Number + Condition: French Score + Condition: Trial Number + French Score: Trial Number + Condition: French Score: Trial Number + (1 + Condition + Trial Number | Participant) + (1 | Item)

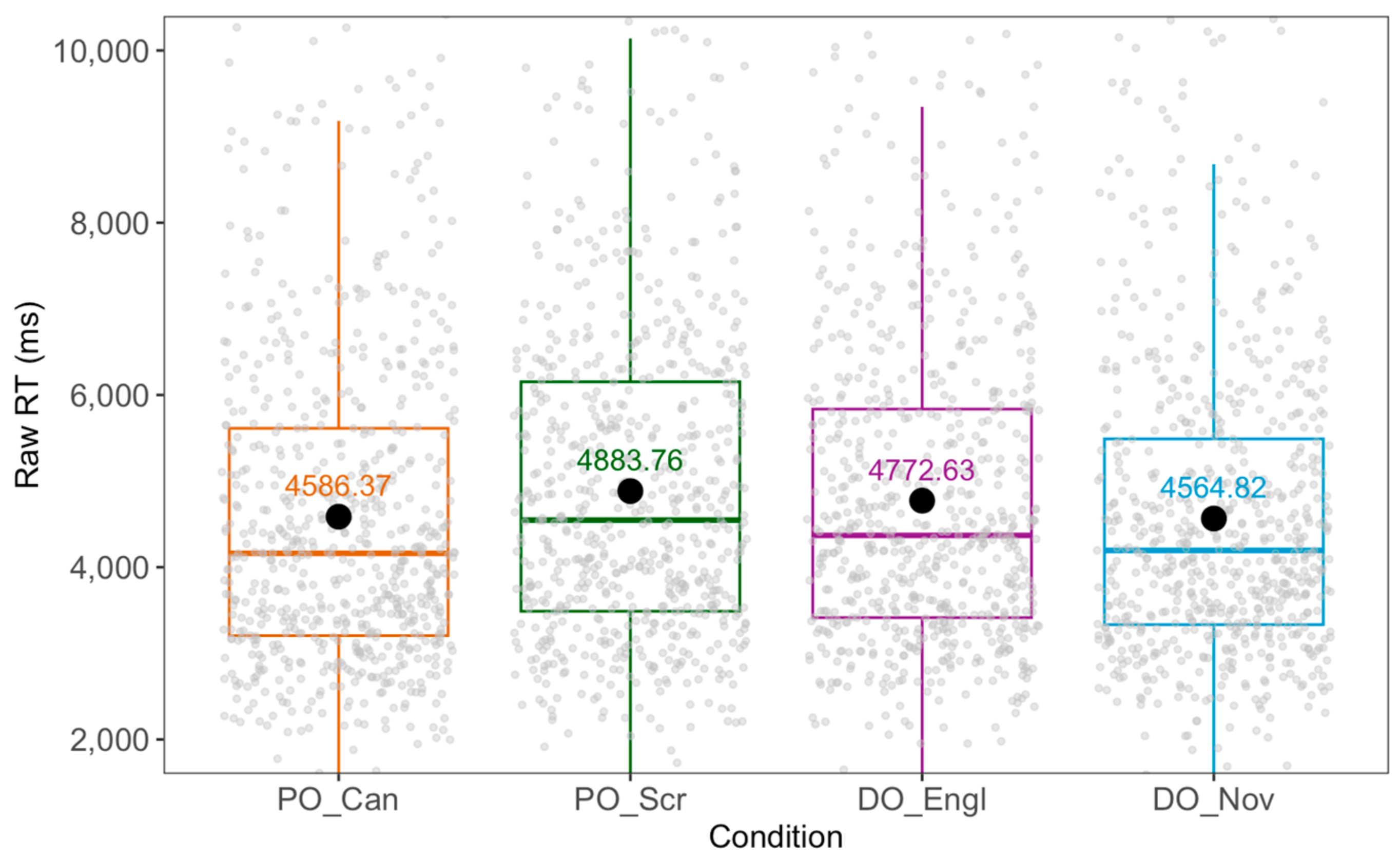

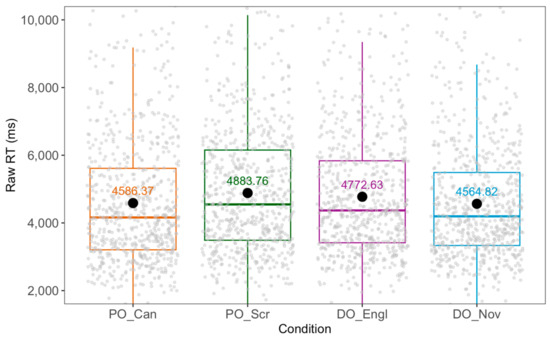

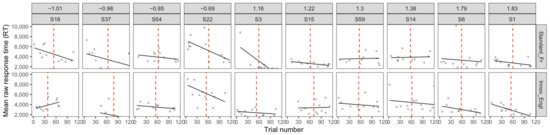

The distribution of individual RTs per condition is shown in Figure 4. Overall, participants were faster in the PO_Can condition than in the PO_Scr condition (β = 0.07, SE = 0.02, t = 4.11, padj = 0.001). However, no significant differences were obtained between PO_Can and DO_Engl (β = 0.04, SE = 0.02, t = 1.73, padj = 0.3), and PO_Can and DO_Nov (β = 0.01, SE = 0.02, t = 0.26, padj = 0.8). Moreover, it was shown that participants responded slower to PO_Scr sentences compared to DO_Nov sentences (β = −0.07, SE = 0.02, t = −3.27, padj = 0.01), but not compared to DO_Engl sentences (β = −0.03, SE = 0.02, t = −1.69, padj = 0.3). The difference between DO_Engl and DO_Nov was also not significant (β = −0.03, SE = 0.02, t = −1.98, padj = 0.2).15

Figure 4.

Distribution of individual raw RTs (gray dots) within the four conditions. The bold horizontal line in each box is the median RT per condition. The black dot is the mean RT (indicated as text).

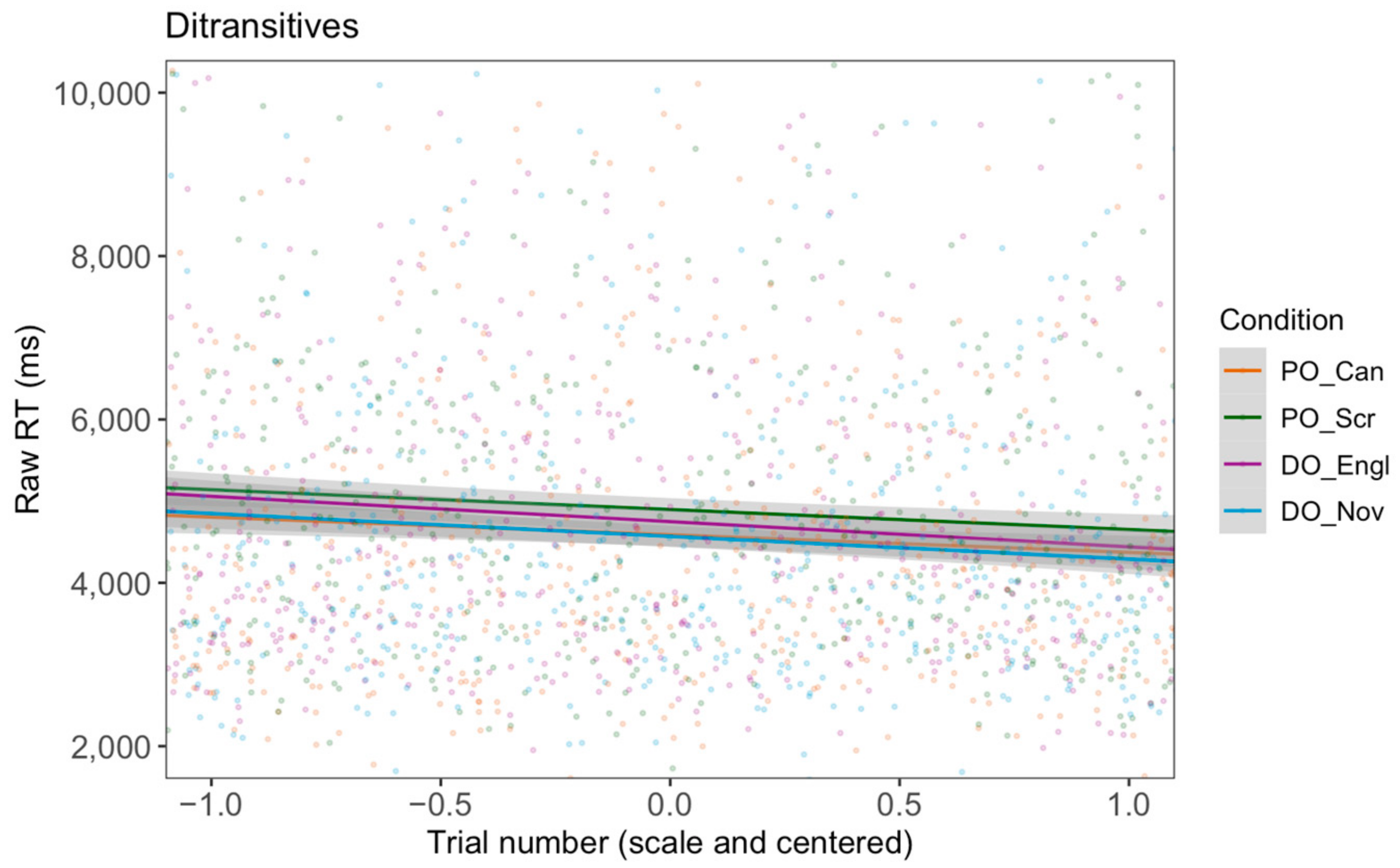

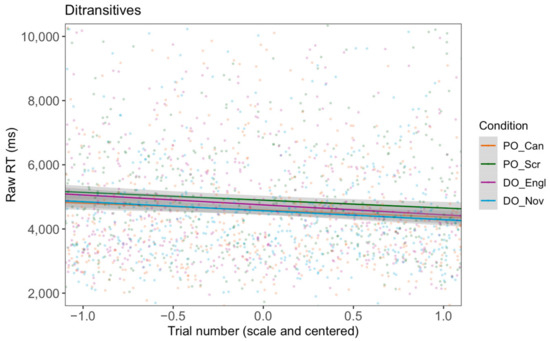

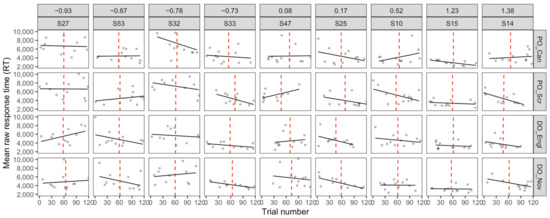

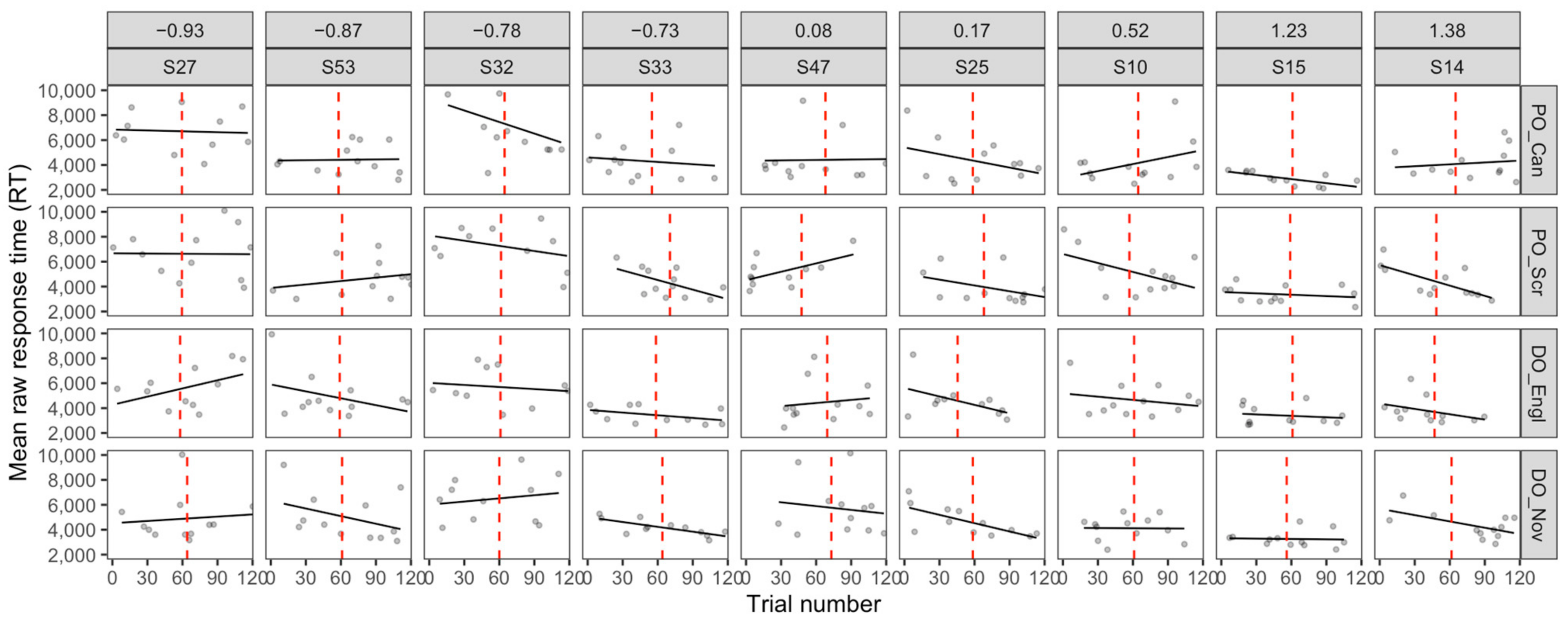

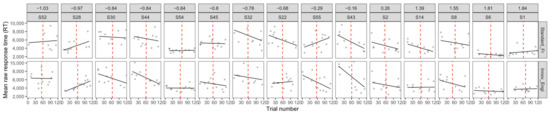

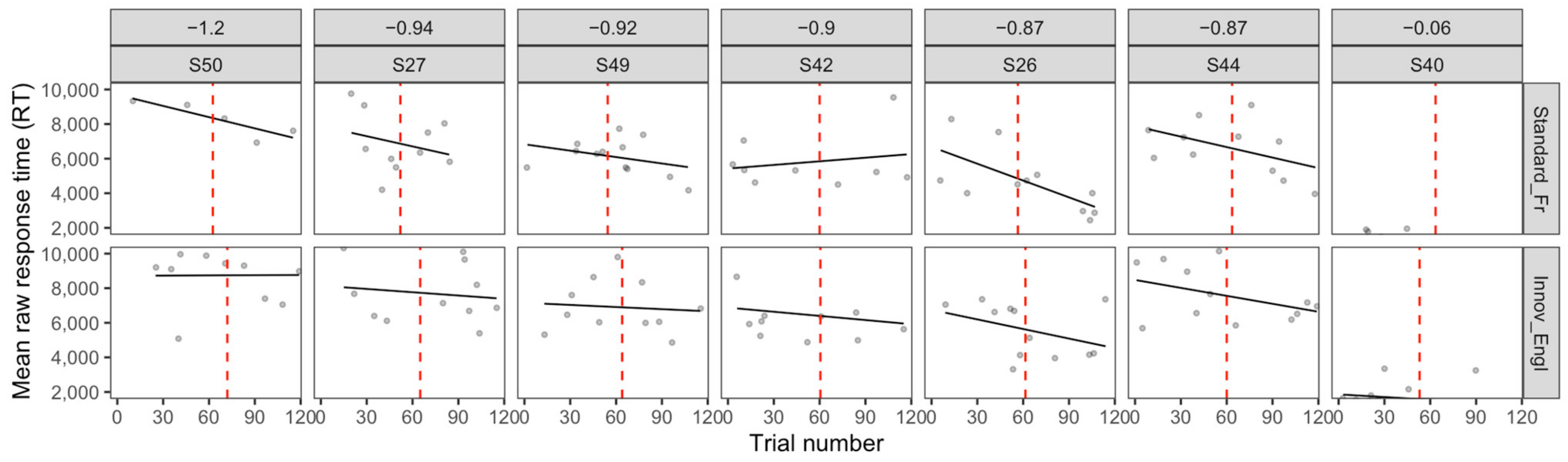

The effect of Trial Number (Figure 5) reached significance in the PO_Can condition, showing that participants became faster at providing a rating as the task proceeded (β = −0.04, SE = 0.02, t = −2.75, p = 0.001). The interactions between Trial Number and Condition showed that, compared to the baseline PO_Can, the effect of Trial Number was not significantly different in the conditions PO_Scr (β = −0.03, SE = 0.02, z = −1.79, p = 0.07), DO_Engl (β = −0.03, SE = 0.02, z = −1.8, p = 0.07), or DO_Nov (β = −0.02, SE = 0.02, z = −1.04, p = 0.3).

Figure 5.

Effect of Trial Number on raw RTs per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the four conditions.

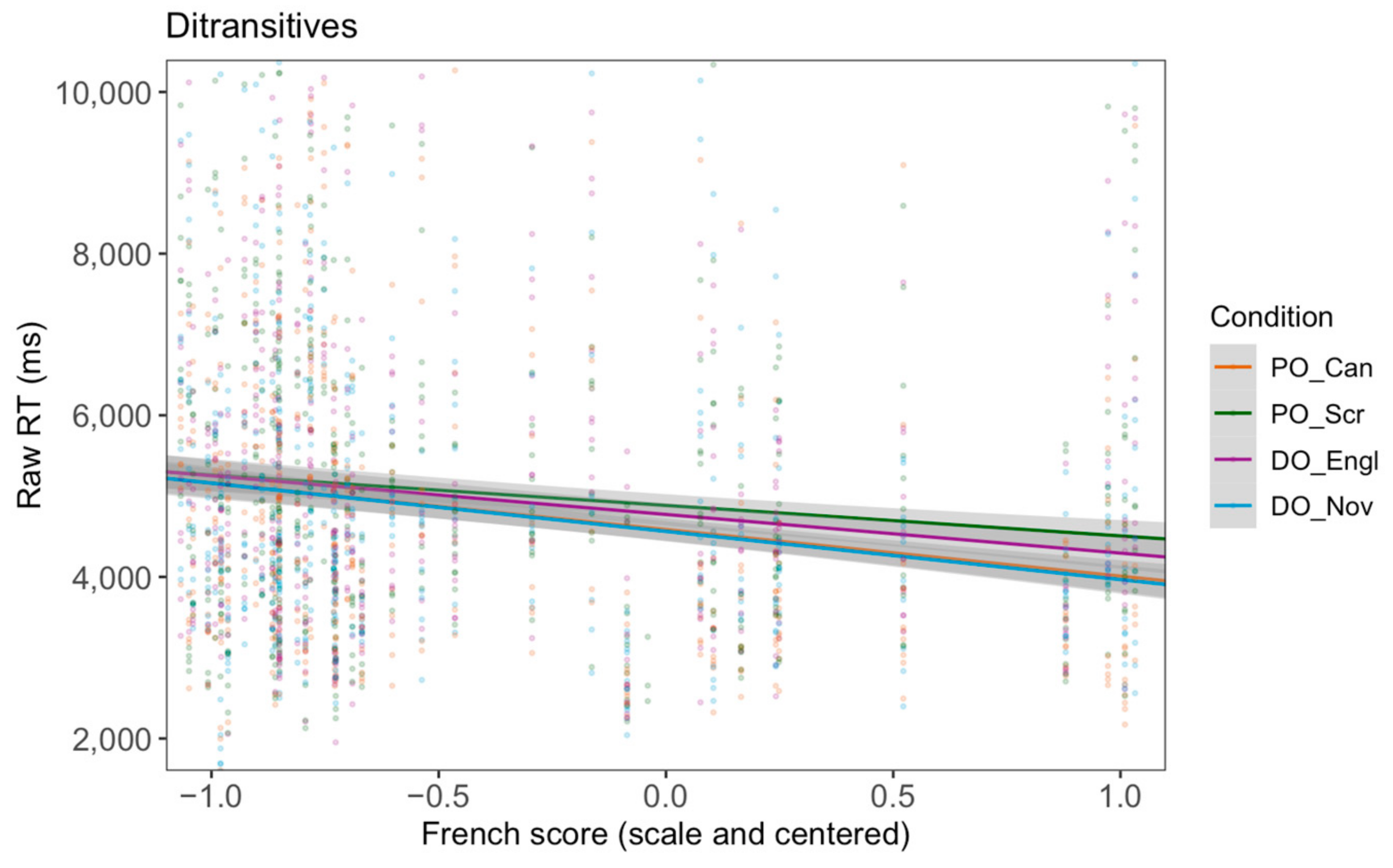

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between RTs and French Score across conditions. The analysis revealed that increasing French Score in participants resulted in a significant decrease in RTs for PO_Can items (β = −0.13, SE = 0.04, t = −3.38, p = 0.001). The interactions between French Score and Condition showed that, compared to PO_Can, the effect of French Score did not change significantly for DO_Engl items (β = 0.03, SE = 0.02, t = 1.26, p = 0.2) and DO_Nov items (β = −0.003, SE = 0.02, t = −0.15, p = 0.9). However, it became less negative for PO_Scr items (β = 0.04, SE = 0.02, t = 2.49, p = 0.02). To obtain the exact effect of French Score in the PO_Scr condition, the model was releveled, and p-values were adjusted. The results show that increasing French Score significantly decreased participants’ RTs in this condition (β = −0.08, SE = 0.04, t = −2.23, padj = 0.03), but this decrease was less strong compared to the PO_Can condition. The releveled model also revealed a significant change in the effect of French Score between PO_Scr and DO_Nov conditions (β = −0.05, SE = 0.02, t = −2.31, p = 0.02). Again, we releveled to DO_Nov, where a higher French Score in participants was found to lead to significantly lower RTs (β = −0.13, SE = 0.04, t = −3.67, padj = 0.002).

Figure 6.

Effect of French Score on raw RTs per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the four conditions.

Additionally, no significant interaction was found between French Score and Trial Number for PO_Can sentences (β = 0.02, SE = 0.02, t = 1.36, p = 0.2), revealing that ratings remained stable across trials in this condition regardless of participants’ French Score. Compared to PO_Can, the effect of this interaction did not change significantly for the other three conditions: PO_Scr (β = −0.03, SE = 0.02, t = −1.73, p = 0.1), DO_Engl (β = −0.004, SE = 0.02, t = −0.27, p = 0.8), and DO_Nov (β = −0.02, SE = 0.02, t = −1.13, p = 0.3).

3.2. Monotransitives

3.2.1. Ratings

Ratings in monotransitive items were analyzed using the ordinal model in (3):

- (3)

- Rating ~ Condition + French Score + Trial Number + Condition: French Score + Condition: Trial Number + French Score: Trial Number + Condition: French Score: Trial Number + (1 + Condition | Participant) + (1 + French Score | Item)

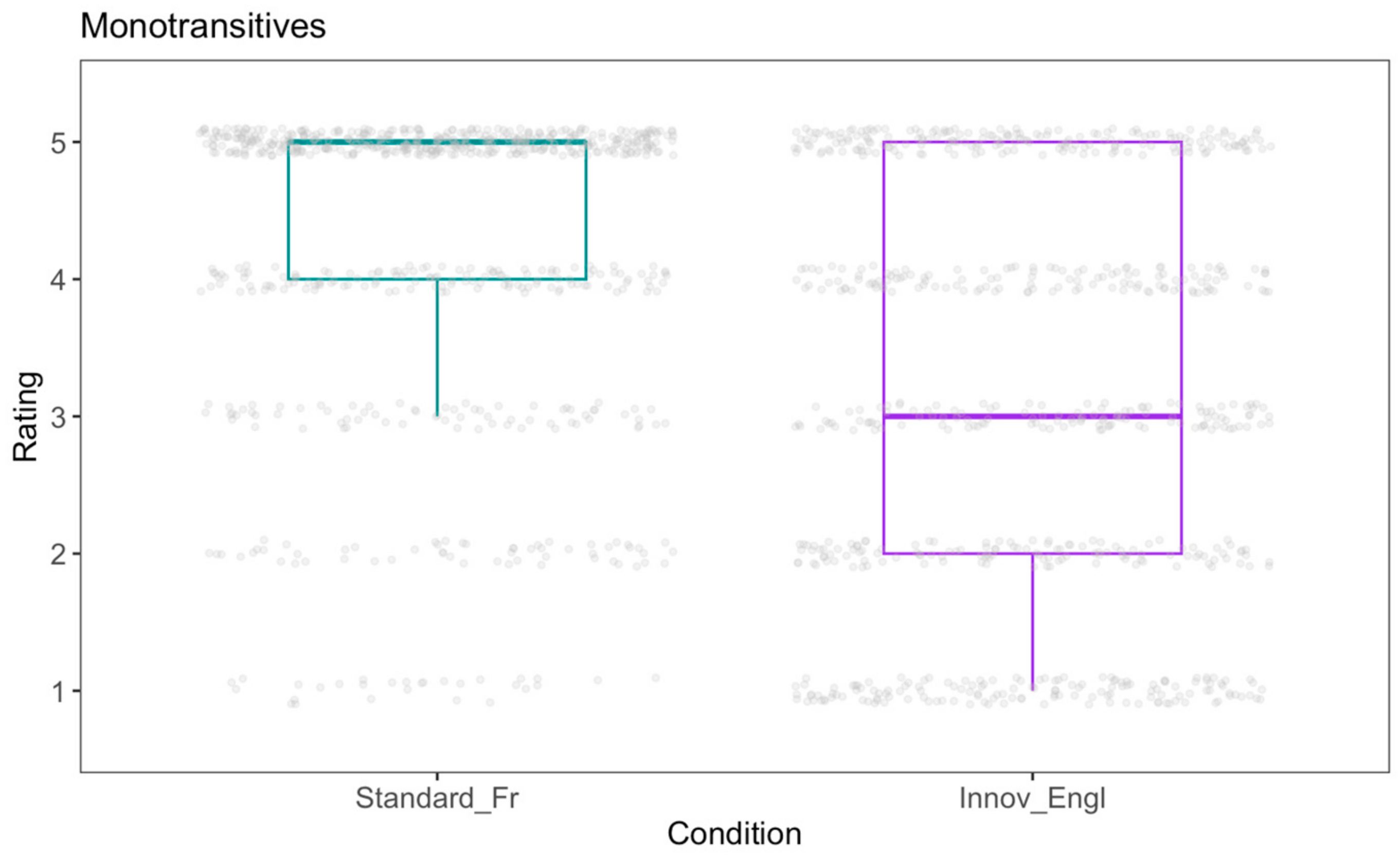

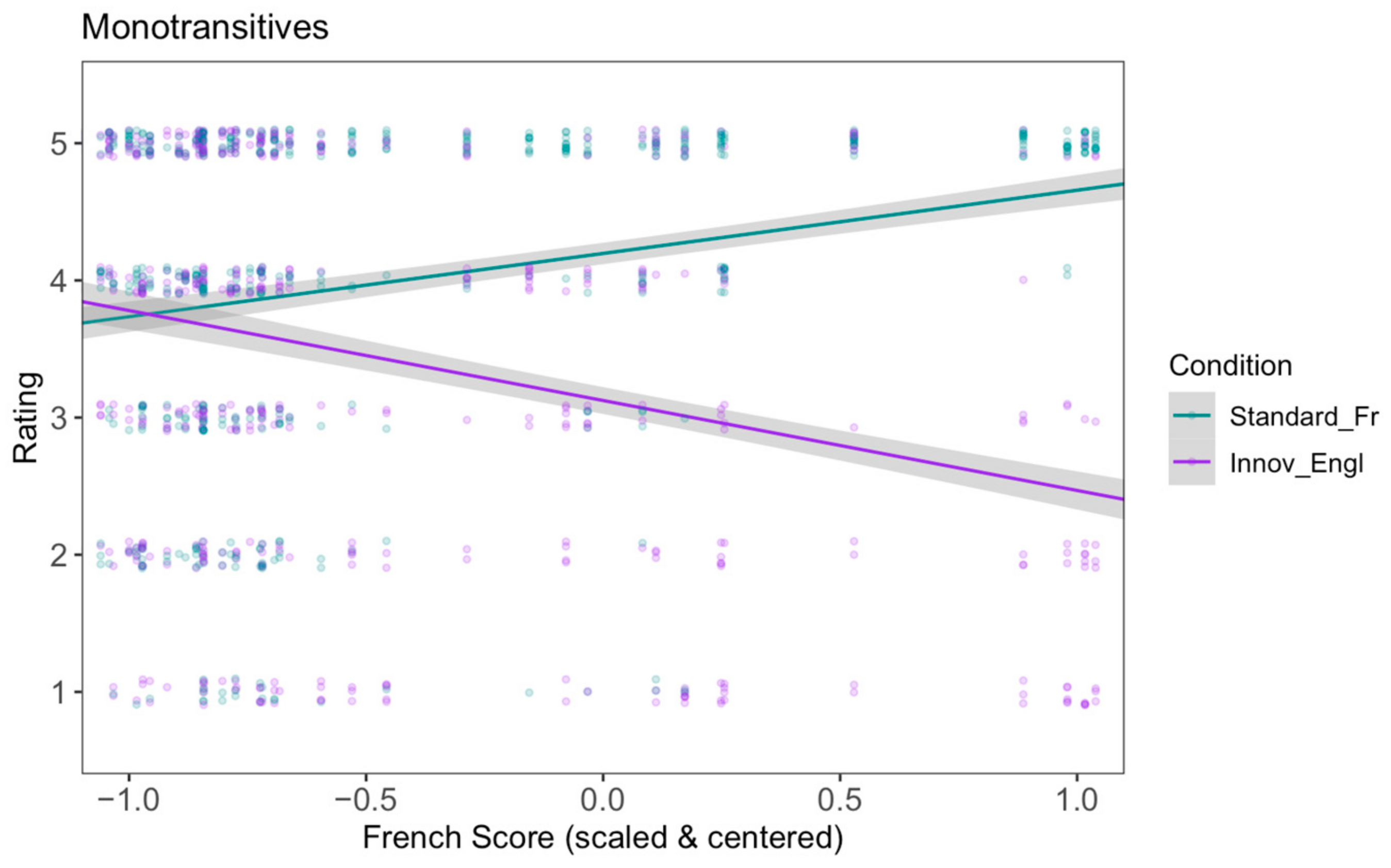

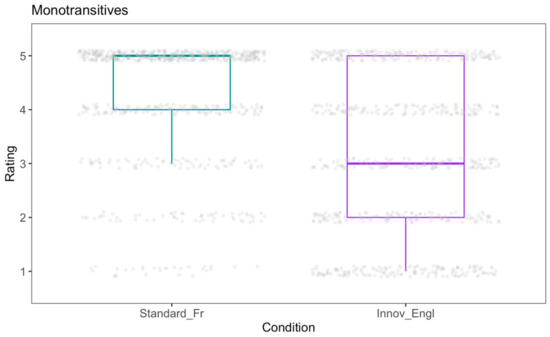

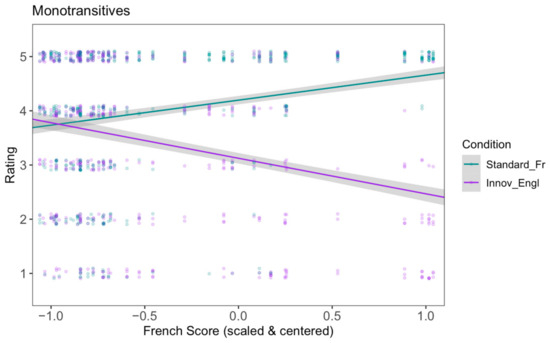

The results show that participants rated Standard_Fr sentences (Le garçon obéit au professeur ‘The boy obeys PREP the teacher’) significantly higher than Innov_Engl sentences (Le garçon obéit le professeur) (β = −2.41, SE = 0.2, z = 12.13, p < 0.0001) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution of individual ratings (gray dots) within the two conditions. The bold horizontal line in each box is the median rating per condition.

The Trial Number (Figure 8) increased participants’ ratings significantly in the Standard_Fr condition (β = 0.19, SE = 0.09, z = 2.01, p = 0.04). The interaction between Trial Number and Condition showed that the effect of Trial Number was not significantly different in the Innov_Engl condition compared to the Standard_Fr condition (β = −0.03, SE = 0.12, z = −0.25, p = 0.8).

Figure 8.

Effect of Trial Number on rating per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

As for the relationship between ratings and French Score (Figure 9), the model revealed that increasing French Score in participants resulted in a significant increase in ratings for Standard_Fr items (β = 1.43, SE = 0.19, z = 7.71, p < 0.0001). The predictor’s interaction with Condition revealed that this effect became more negative for Innov_Engl items compared to Standard_Fr items (β = −2.64, SE = 0.21, z = −12.49, p < 0.0001). We releveled the model to obtain the exact effect of French Score and found that an increasing French Score in participants led to a decrease in ratings for Innov_Engl sentences (β = −1.21, SE = 0.17, z = −7.14, padj < 0.0001).

Figure 9.

Effect of French Score on rating per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

French Score and Trial Number did not interact significantly in the Standard_Fr condition (β = 0.07, SE = 0.11, z = 0.62, p = 0.5), indicating that an increasing French Score in participants did not lead to increasing ratings throughout the task. The effect of this interaction did not significantly change in the Innov_Engl condition compared to the Standard_Fr condition (β = −0.15, SE = 0.13, z = −1.13, p = 0.3).

3.2.2. Response Times

Log-transformed RTs in monotransitive items were analyzed using the linear mixed model in (4):

- (4)

- Log RT ~ Condition + French Score + Trial Number + Condition: French Score + Condition: Trial Number + French Score: Trial Number + Condition: French Score: Trial Number + (1 + Trial Number | Participant) + (1 | Item)

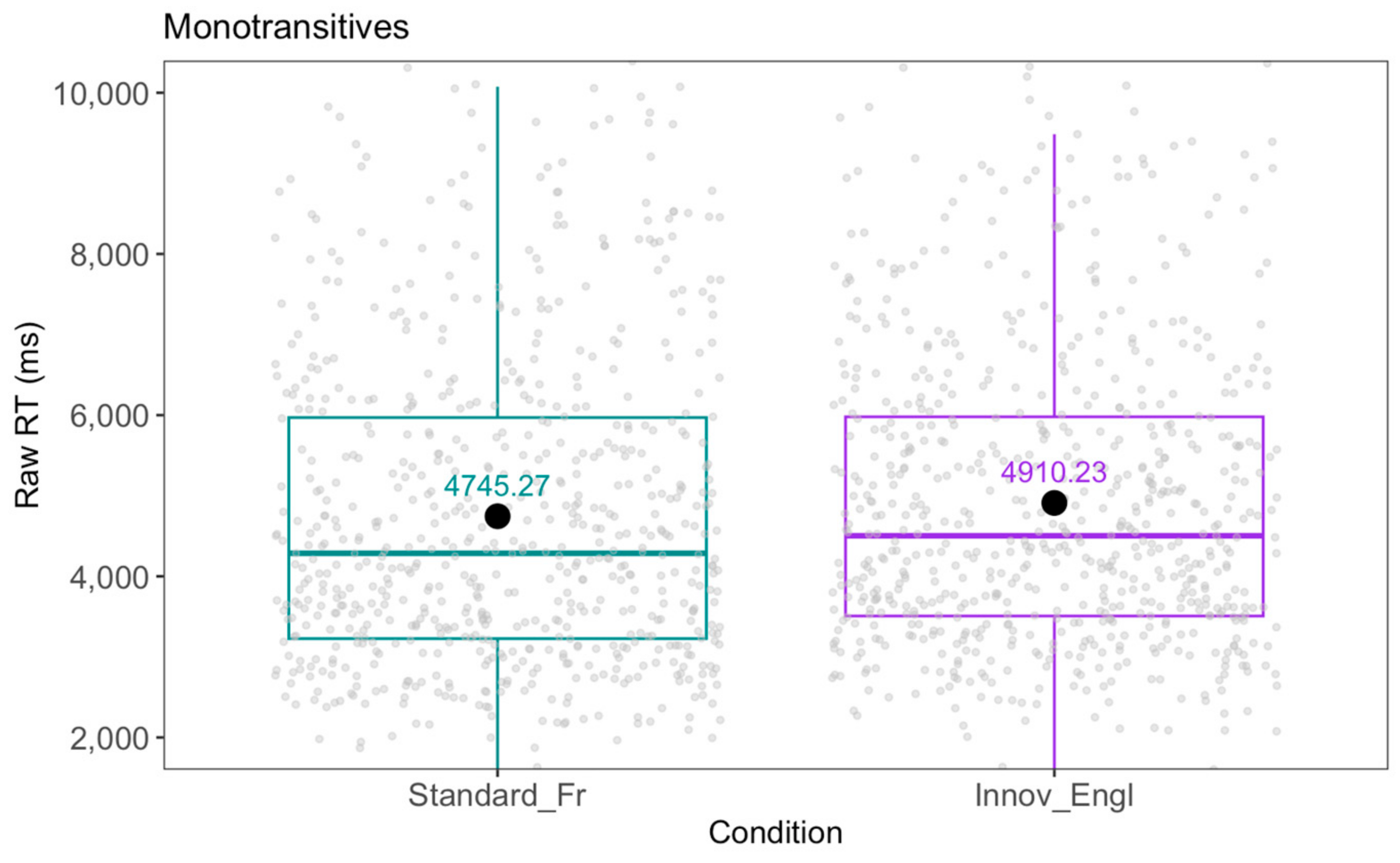

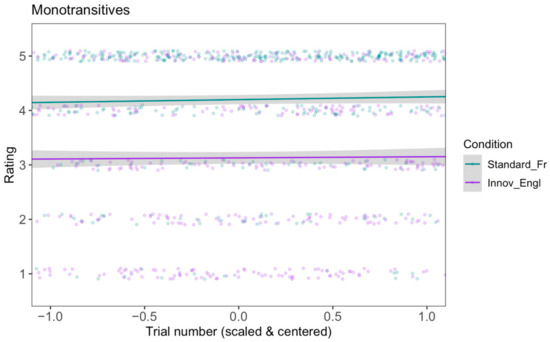

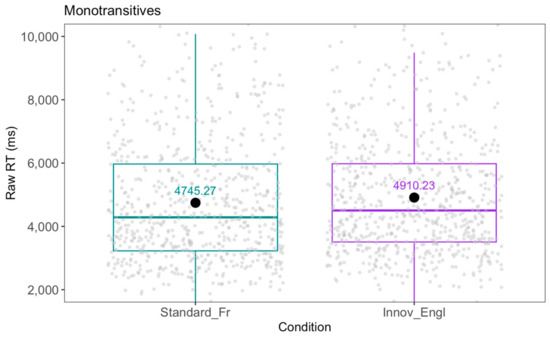

Figure 10 illustrates the distribution of individual RTs in each of the two conditions. Overall, Standard_Fr items were rated significantly faster than Innov_Engl items (β = 0.03, SE = 0.02, t = 2.21, p = 0.03).

Figure 10.

Distribution of individual raw RTs (gray dots) within the two conditions. The bold horizontal line in each box is the median RT per condition. The black dot is the mean RT (indicated as text).

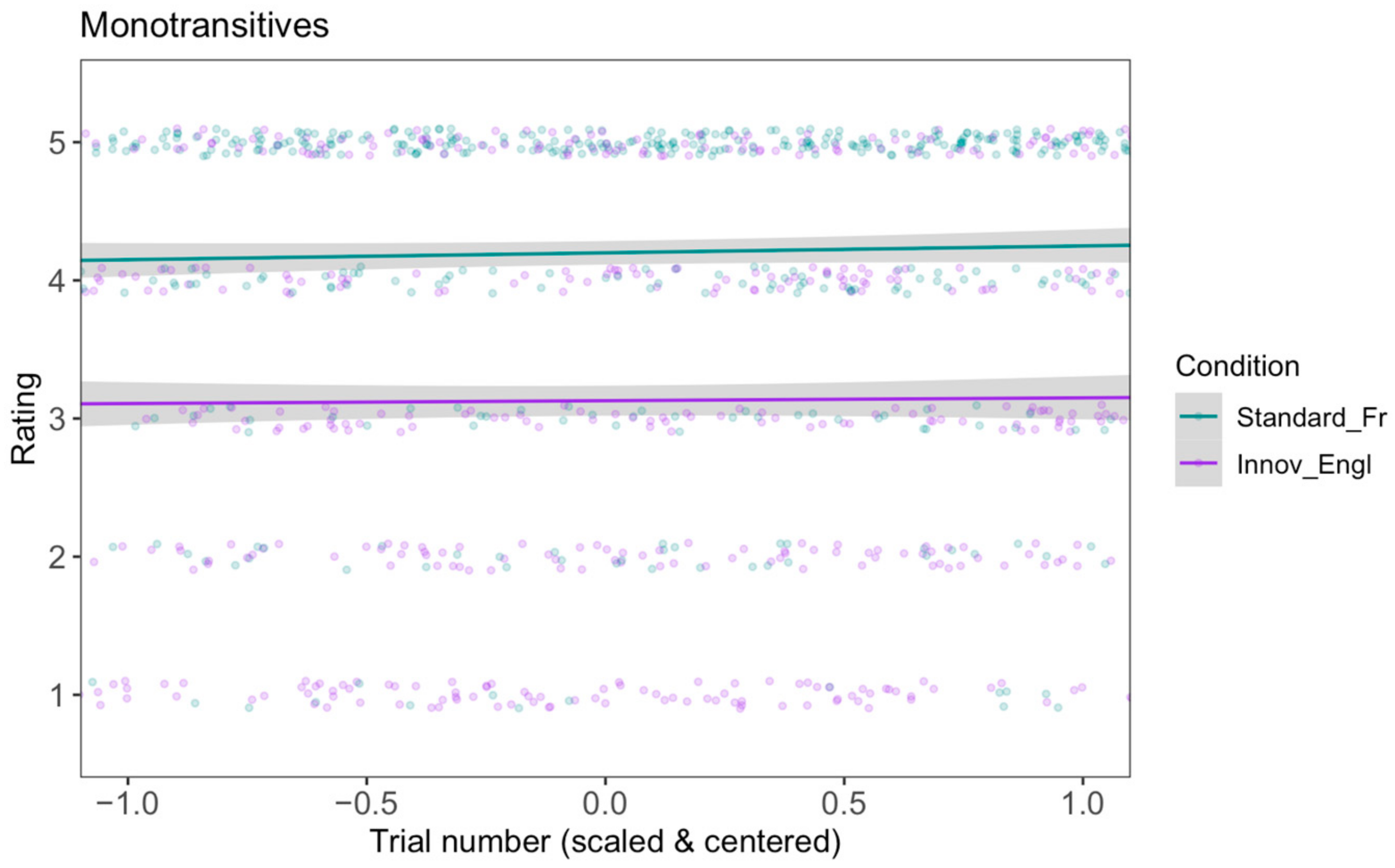

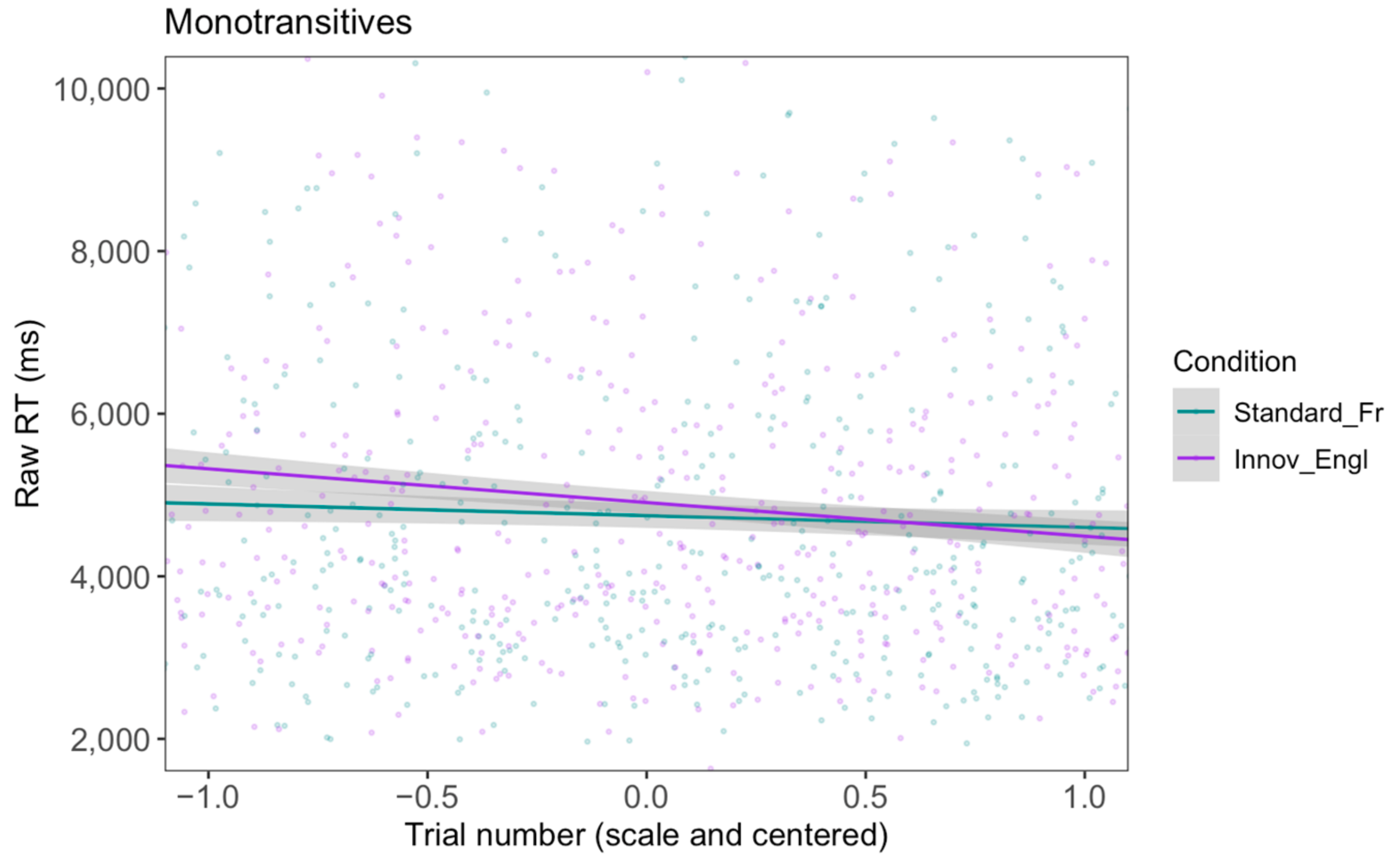

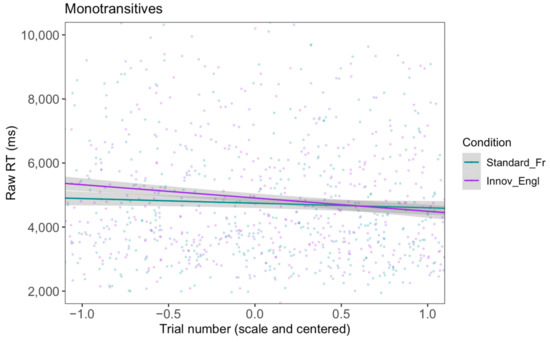

Trial Number (Figure 11) was also shown to have an effect, with participants becoming faster throughout the task in rating Standard_Fr items (β = −0.04, SE = 0.02, t = −3.03, p = 0.003). The interaction between Trial Number and Condition revealed no significant change in the effect of Trial Number for Innov_Engl items compared to Standard_Fr items (β = −0.03, SE = 0.02, t = −1.66, p = 0.1).

Figure 11.

Effect of Trial Number on raw RTs per condition. The gray area around each line is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

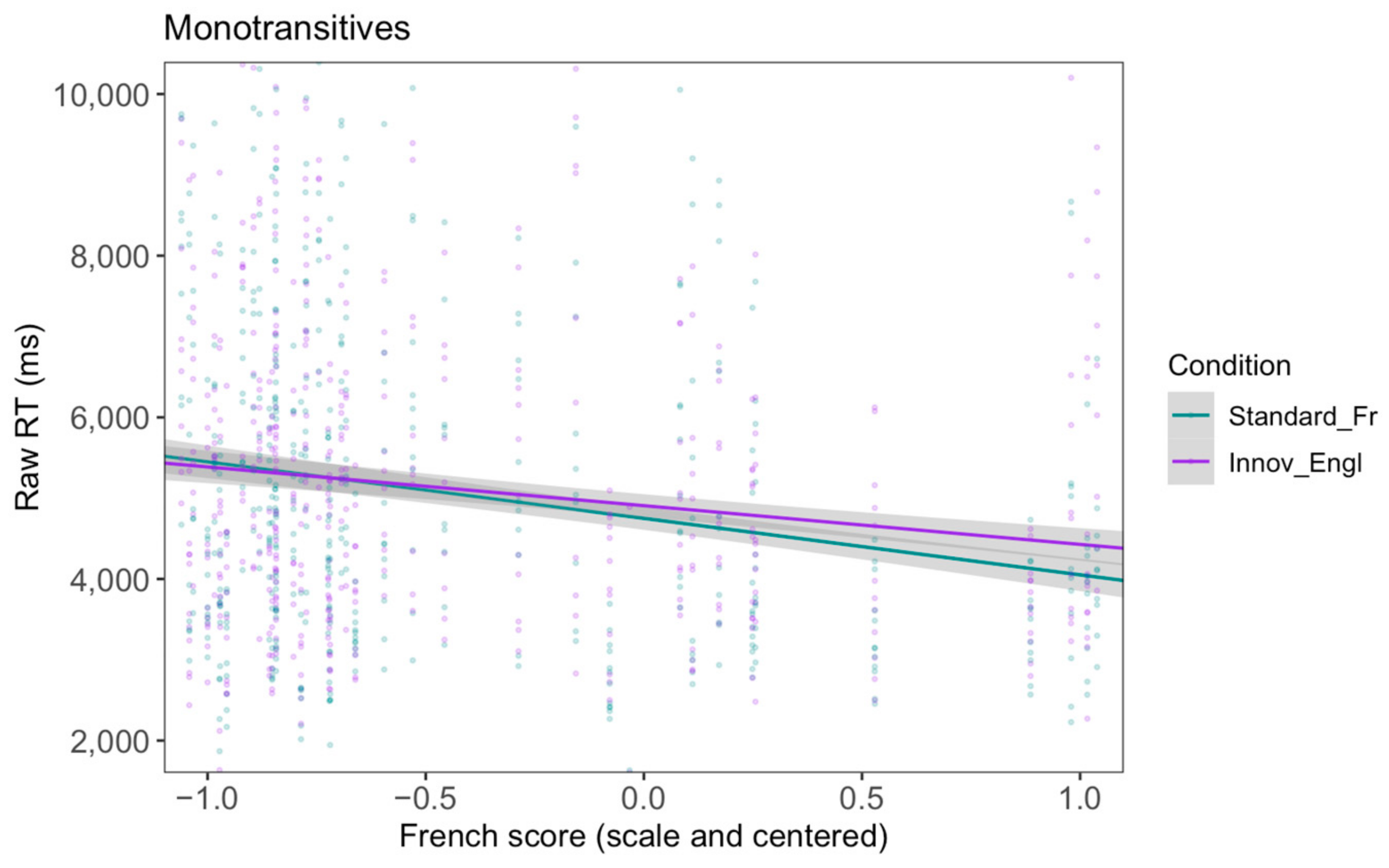

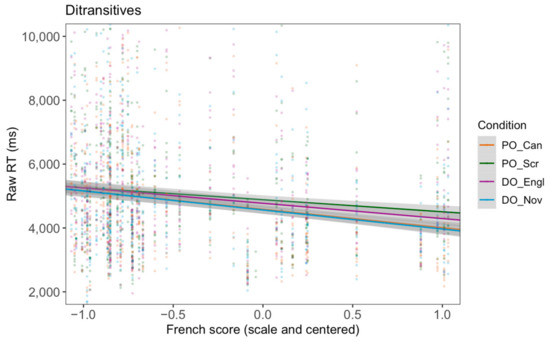

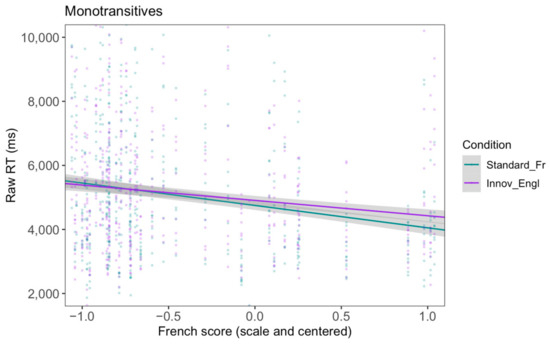

As for the effect of French Score on RTs (Figure 12), an increasing French Score in participants resulted in significantly decreasing RTs for Standard_Fr sentences (β = −0.15, SE = 0.04, t = −3.89, p = 0.0002). Its interaction with Condition showed that the effect of French Score was less negative for Innov_Engl sentences compared to Standard_Fr sentences (β = 0.06, SE = 0.02, t = 4.01, p < 0.0001). The model was releveled to obtain the exact effect of the predictor in the Innov_Engl condition, and it revealed a decreasing but less strong tendency compared to the Standard_Fr condition (β = −0.08, SE = 0.04, t = −2.29, padj = 0.03).

Figure 12.

Effect of French Score on raw RTs per condition. The gray area around each line is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

As for the two-way interaction between French Score and Trial Number, it was not significant, indicating that participants did not rate Standard_Fr sentences faster across trials because of their French Score (β = 0.01, SE = 0.02, t = 0.88, p = 0.4). Compared to Standard_Fr, the effect of this interaction was not significantly different for the Innov_Engl condition (β = 0.02, SE = 0.02, t = 1.19, p = 0.2).

3.3. Reciprocals

3.3.1. Ratings

Ratings in reciprocal items were analyzed using the ordinal model in (5):

- (5)

- Rating ~ Condition + French Score + Trial Number + Condition: French Score + Condition: Trial Number + French Score: Trial Number + Condition: French Score: Trial Number + (1 + Condition | Participant) + (1 + Condition + French Score | Item)

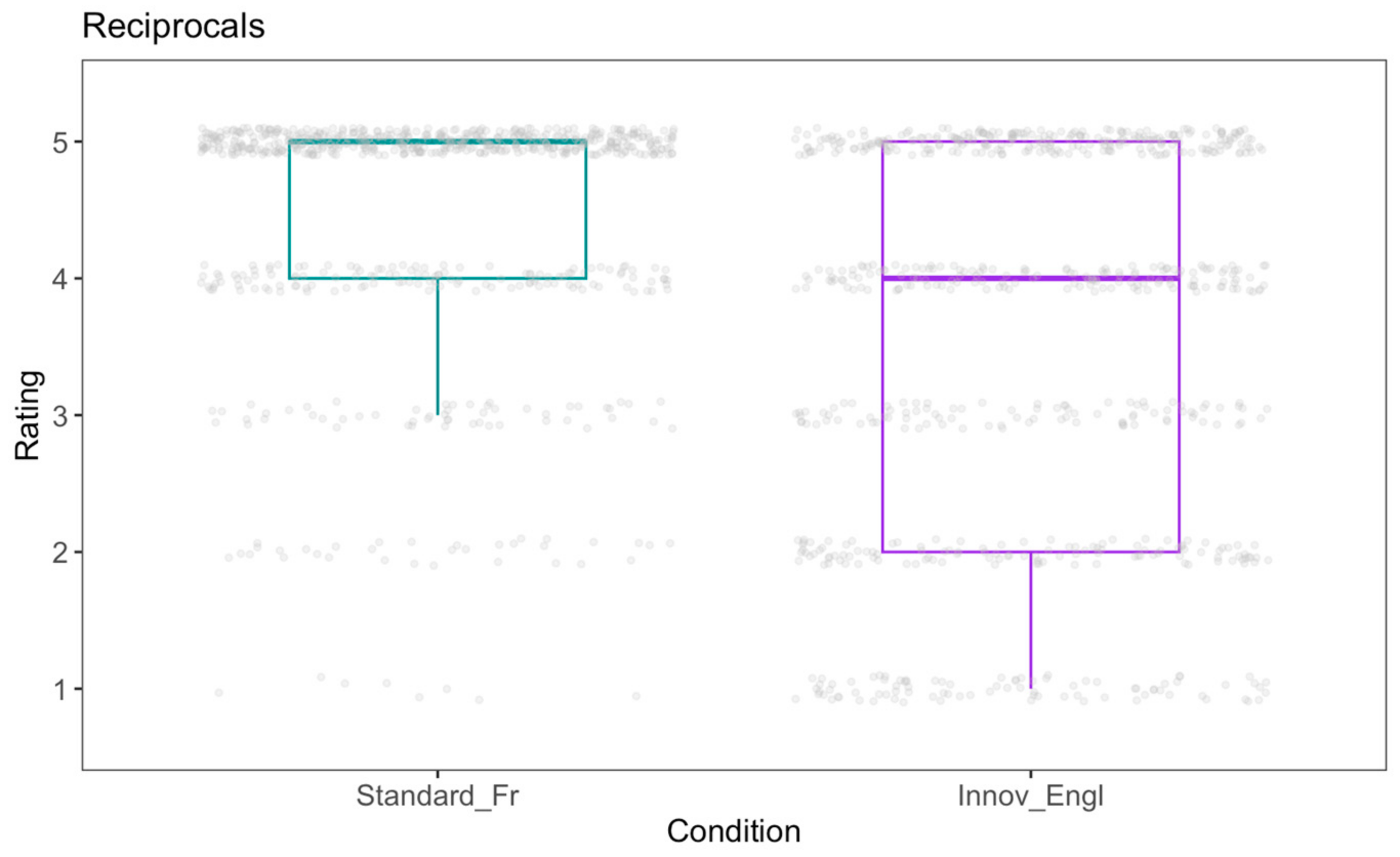

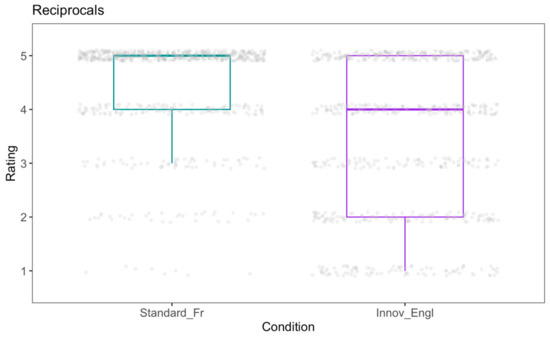

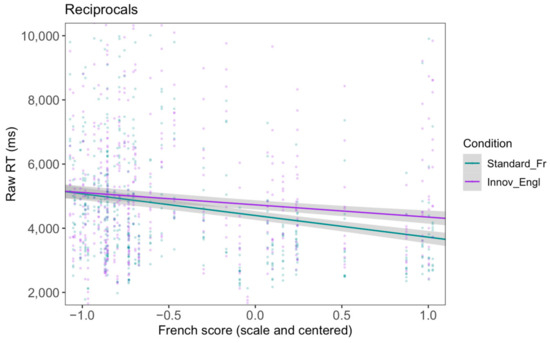

The results showed that Standard_Fr sentences (Les deux amis s’embrassent ‘The two friends REFL hug’) yielded significantly higher acceptability than Innov_Engl sentences (Les deux amis embrassent ‘The two friends hug’) (β = −2.86, SE = 0.34, z = −8.29, p < 0.0001) (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Distribution of individual ratings (gray dots) within the two conditions. The bold horizontal line in each box is the median rating per condition.

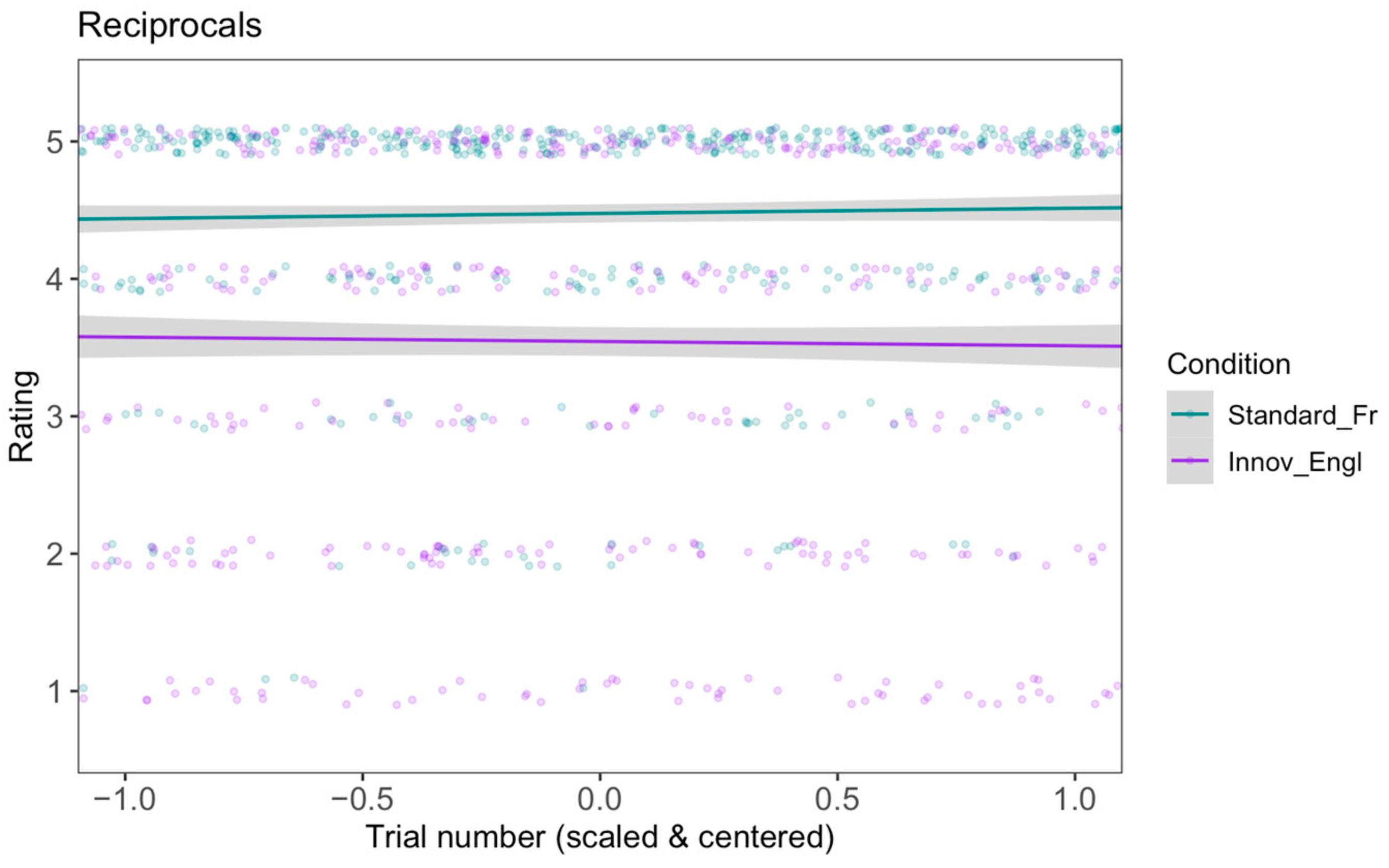

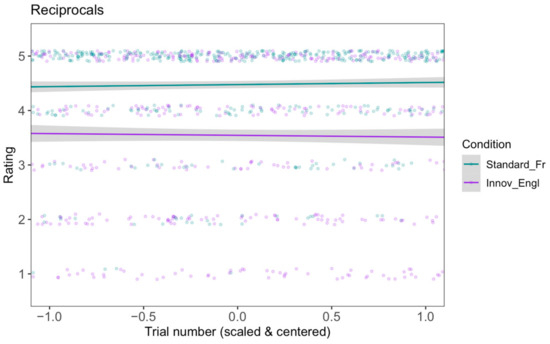

Trial Number (Figure 14) did not affect participants’ ratings significantly in the Standard_Fr condition (β = 0.09, SE = 0.12, z = 0.77, p = 0.4). Also, the interaction between Trial Number and Condition showed that the predictor’s effect was not significantly different in the Innov_Engl condition compared to the Standard_Fr condition (β = −0.19, SE = 0.14, z = −1.39, p = 0.2).

Figure 14.

Effect of Trial Number on rating per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

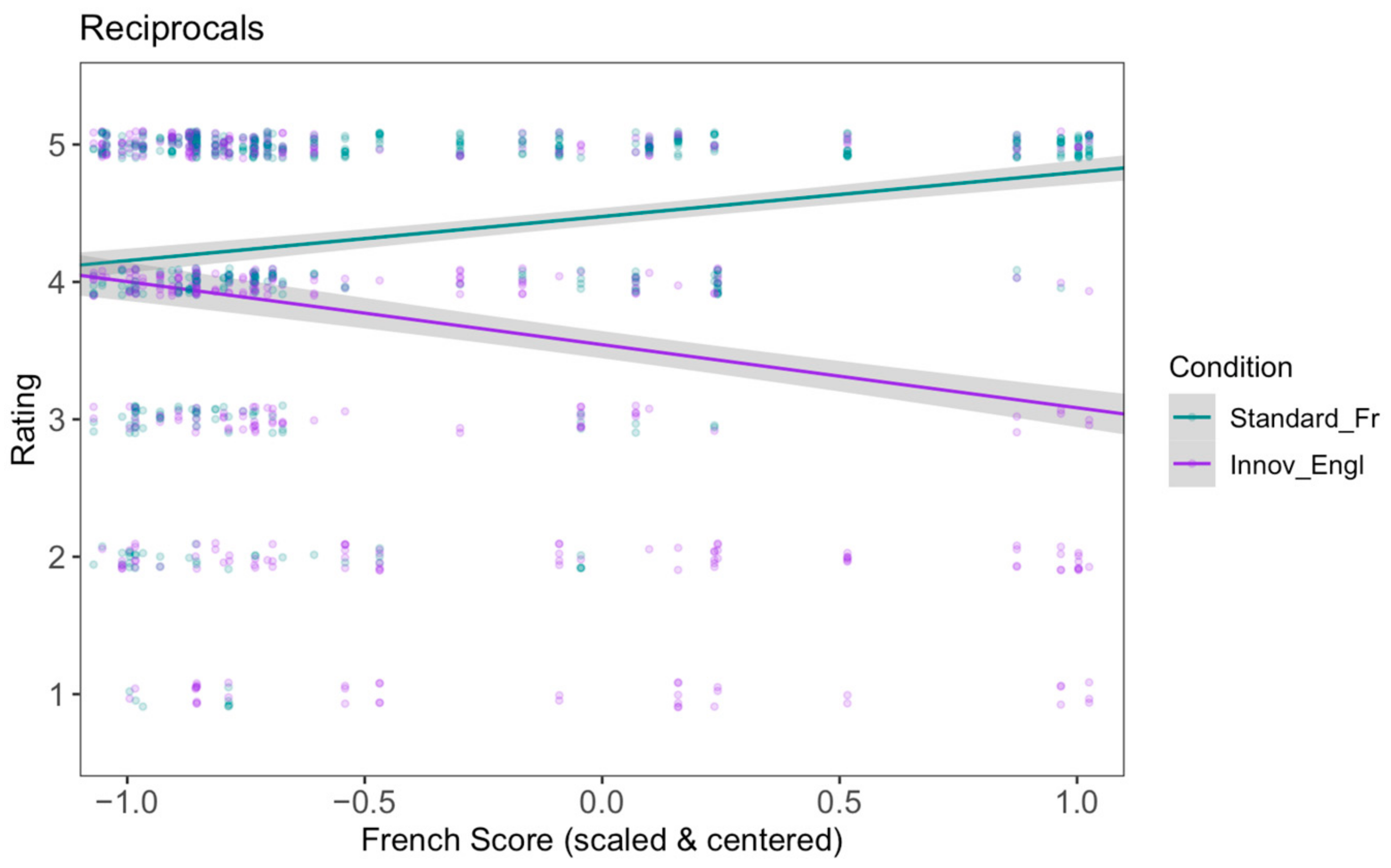

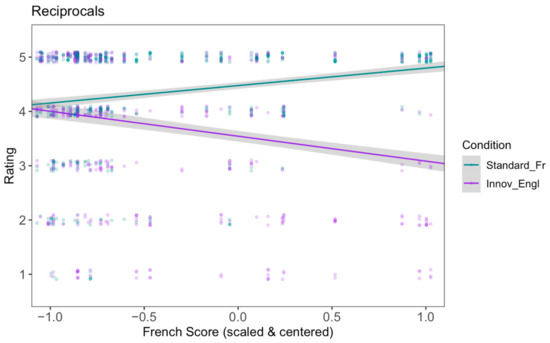

Figure 15 illustrates the relationship between ratings and French Score within the two conditions. The model shows that, for Standard_Fr items, an increasing French Score in participants led to significantly higher ratings (β = 1.86, SE = 0.33, z = 5.59, p < 0.0001). The interaction between French Score and Condition revealed that the effect of French Score was more negative for Innov_Engl items that for Standard_Fr items (β = −2.72, SE = 0.3, z = −9.18, p < 0.0001). The model was releveled to obtain the exact effect of the predictor in the Innov_Engl condition, and revealed the opposite pattern, namely that an increasing French Score in participants led to decreasing ratings (β = −0.86, SE = 0.29, z = −3.02, padj = 0.003).

Figure 15.

Effect of French Score on rating per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

French Score and Trial Number did not interact significantly in the Standard_Fr condition (β = −0.08, SE = 0.14, z = −0.59, p = 0.6), showing that an increasing French Score in participants did not lead to a significant increase in ratings as the task proceeded. Compared to Standard_Fr, the effect of this interaction was not significantly different in the Innov_Engl condition (β = 0.29, SE = 0.16, z = 1.8, p = 0.1).

3.3.2. Response Times

Log-transformed response times (RTs) in reciprocal items were analyzed using the linear mixed model in (6):

- (6)

- Log RT ~ Condition + French Score + Trial Number + Condition: French Score + Condition: Trial Number + French Score: Trial Number + Condition: French Score: Trial Number + (1 + Condition + Trial Number | Participant) + (1 | Item)

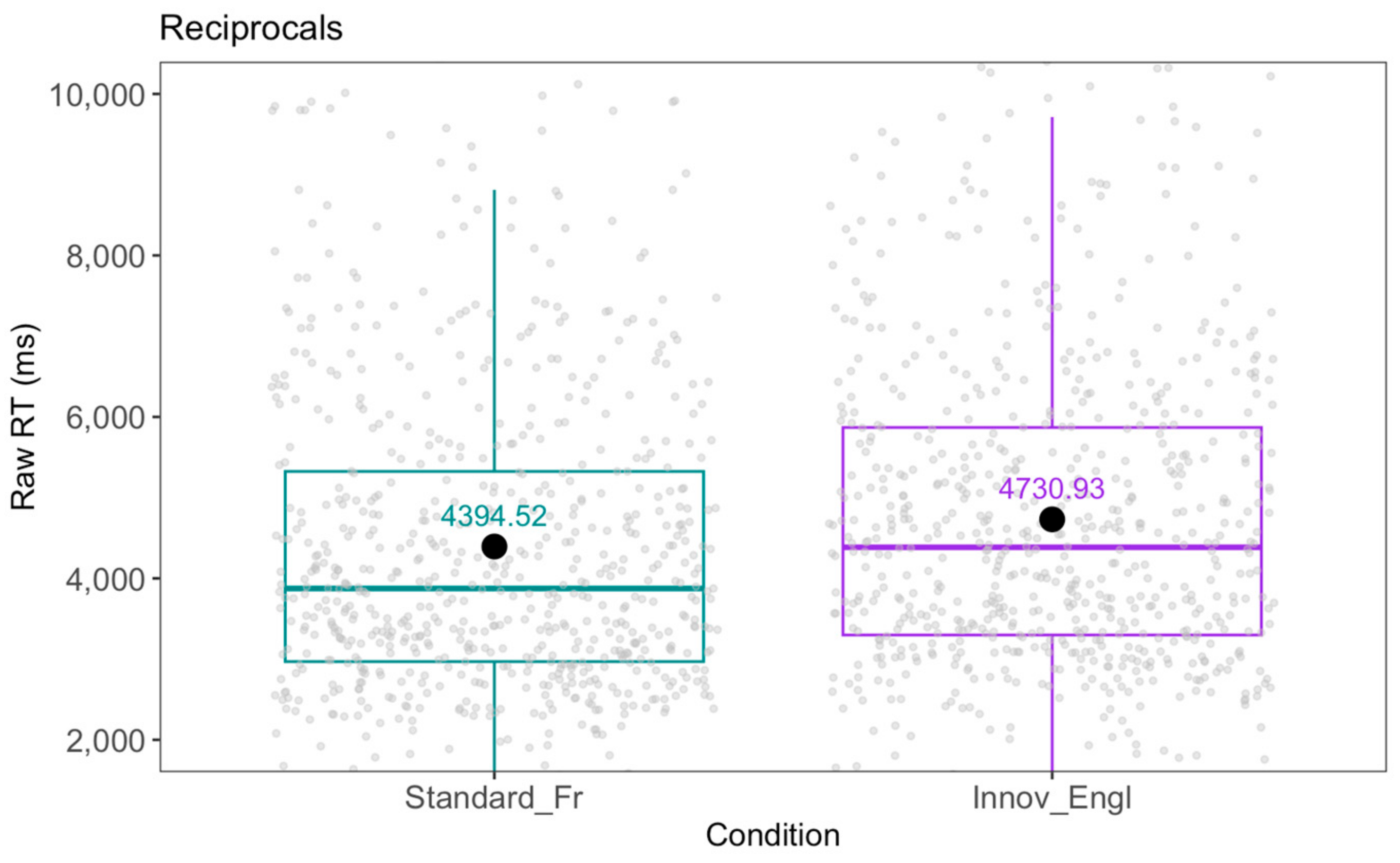

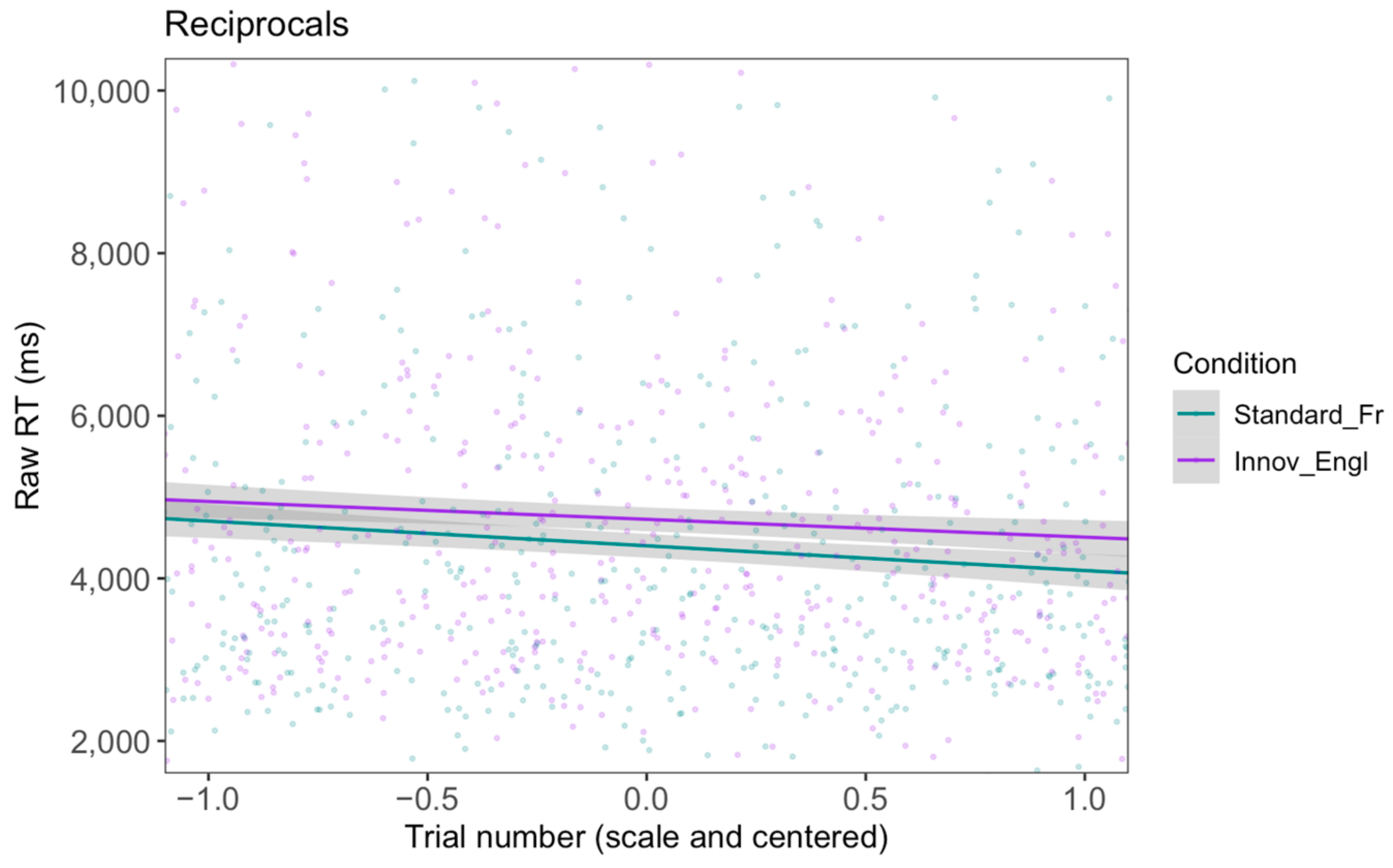

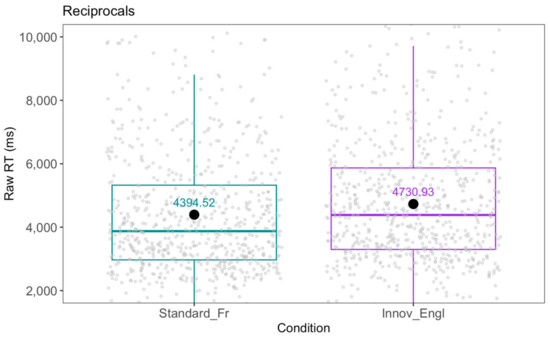

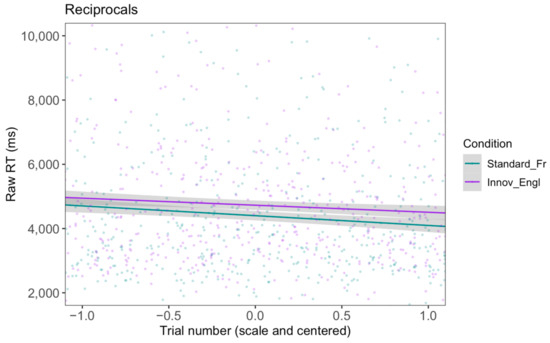

Overall, participants rated Standard_Fr items significantly faster than Innov_Engl items (β = 0.07, SE = 0.02, t = 3.43, p = 0.001) (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Distribution of individual raw RTs (gray dots) within the two conditions. The bold horizontal line in each box is the median RT per condition. The black dot is the mean RT (indicated as text).

An increasing Trial Number (Figure 17) was shown to lead to a decrease in RTs in the Standard_Fr condition (β = −0.06, SE = 0.01, t = −4.79, p < 0.0001). The interaction between Trial Number and Condition showed that, compared to Standard_Fr, the effect of Trial Number did not change significantly in the Innov_Engl condition (β = 0.008, SE = 0.02, t = 0.49, p = 0.6).

Figure 17.

Effect of Trial Number on raw RTs per condition. The gray area around each line is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

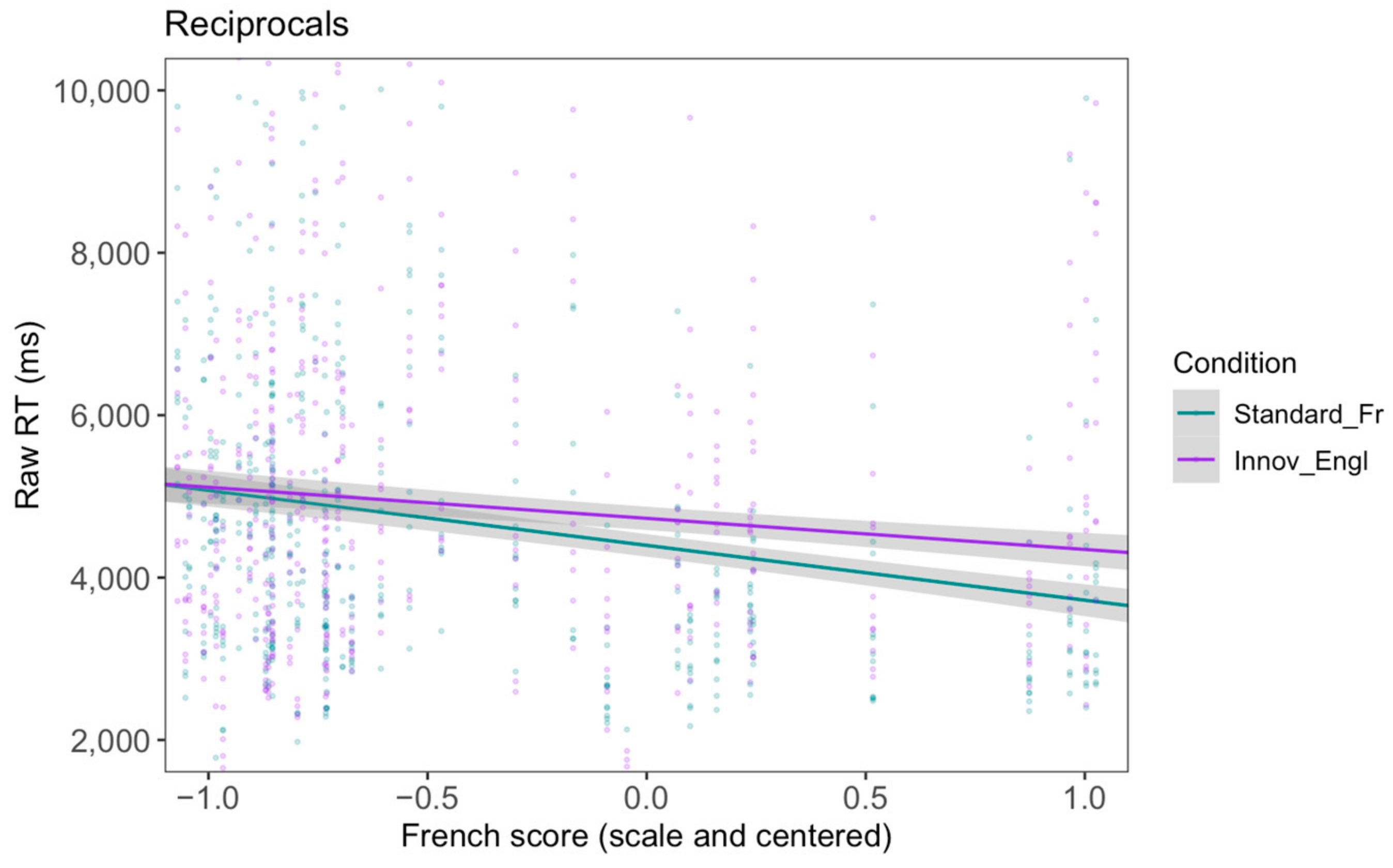

Regarding French Score (Figure 18), we detected a significant decrease in RTs with increasing French Score for the Standard_Fr sentences (β = −0.16, SE = 0.04, t = −4.42, p < 0.0001). The interaction between French Score and Condition revealed that the effect of French Score was less negative for the Innov_Engl sentences compared to Standard_Fr sentences (β = 0.08, SE = 0.02, t = 4.14, p = 0.0001). In the releveled model, it was shown that participants with an increasing French Score again showed lower RTs in this condition (β = −0.08, SE = 0.04, t = −1.92, padj = 0.06), but less strongly compared to Standard_Fr.

Figure 18.

Effect of French Score on raw RTs per condition. The gray area around each line is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

As for the two-way interaction between French Score and Trial Number, it was not significant in the Standard_Fr condition, indicating that, regardless of their French Score, participants did not rate these sentences faster as the task proceeded (β = 0.002, SE = 0.01, t = 0.14, p = 0.9). This effect did not change significantly in the Innov_Engl condition compared to the Standard_Fr condition (β = −0.01, SE = 0.02, t = −0.57, p = 0.6).

3.4. Object Clitics

3.4.1. Ratings

Ratings in object clitic items were analyzed using the ordinal model in (7):

- (7)

- Rating ~ Condition + French Score + Trial Number + Condition: French Score + Condition: Trial Number + French Score: Trial Number + Condition: French Score: Trial Number + (1 + Condition | Participant) + (1 + Condition + French Score | Item)

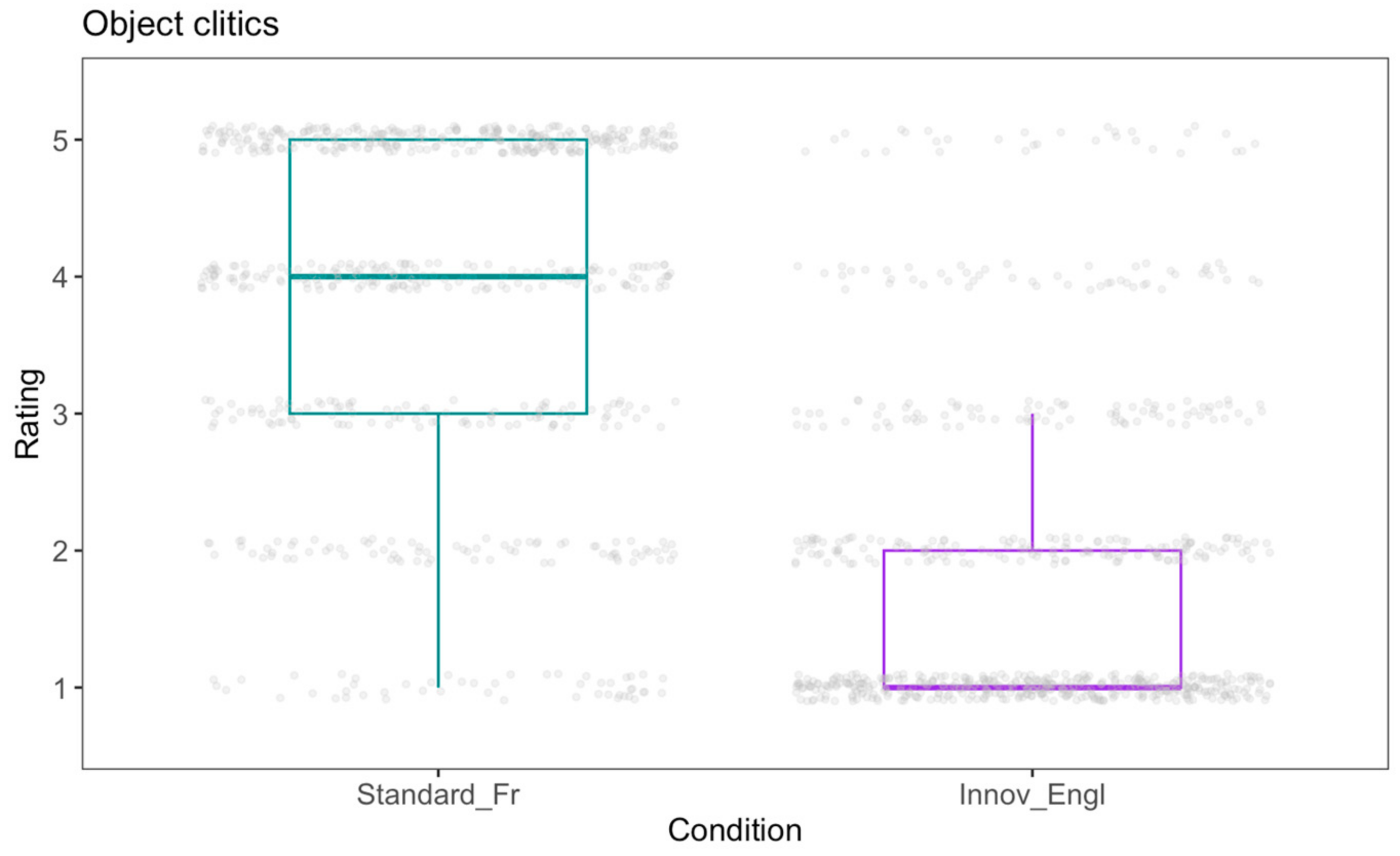

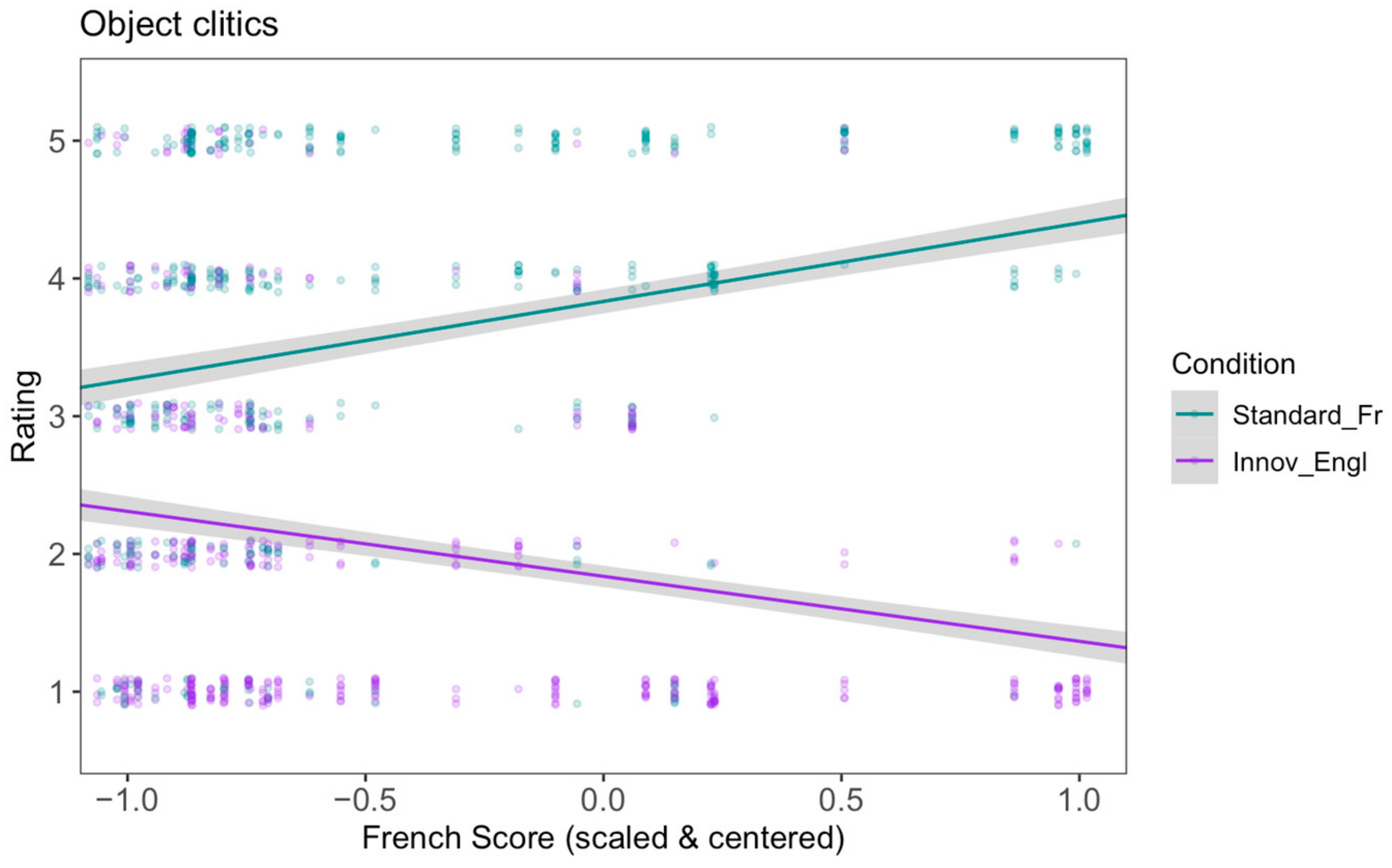

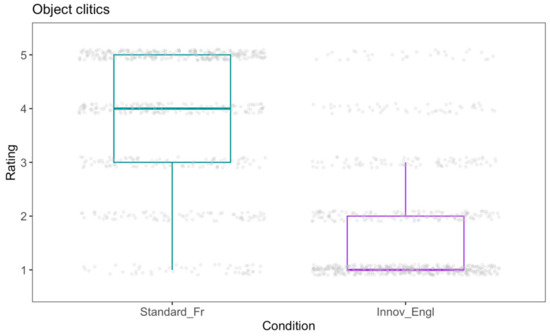

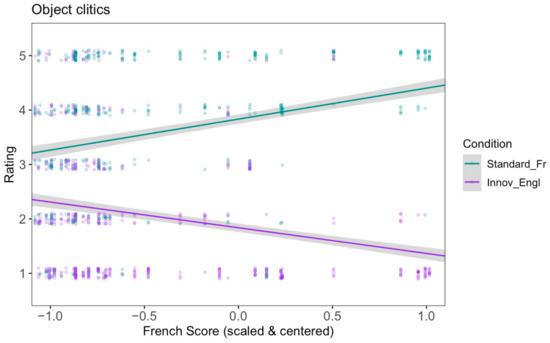

Overall, participants accepted Standard_Fr sentences (Il les met sur la table ‘He them puts on the table’) significantly more than Innov_Engl sentences (Ils met les sur la table ‘He puts them on the table’) (β = −4.9, SE = 0.39, z = −12.41, p < 0.0001) (Figure 19).

Figure 19.

Distribution of individual ratings (gray dots) within the two conditions. The bold horizontal line in each box is the median rating per condition.

Throughout the task, an increasing Trial Number (Figure 20) was shown to lead to a significant increase in participants’ ratings for Standard_Fr items (β = 0.21, SE = 0.09, z = 2.3, p = 0.02). The interaction between Trial Number and Condition revealed that, compared to Standard_Fr, the effect of Trial Number was not significantly different in the Innov_Engl condition (β = −0.17, SE = 0.13, z = −1.25, p = 0.2).

Figure 20.

Effect of Trial Number on rating per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

French Score (Figure 21) was found to be a significant predictor for Standard_Fr items, causing an increase in ratings as it increased (β = 1.48, SE = 0.22, z = 6.6, p < 0.0001). The interaction between French Score and Condition showed that the effect of French Score was more negative in the Innov_Engl condition than in the Standard_Fr condition (β = −3.19, SE = 0.38, z = −8.34, p < 0.0001). The releveled model revealed that French Score had the opposite effect on these sentences, leading to a significant decrease in ratings with increasing French Score in participants (β = −1.71, SE = 0.32, z = −5.35, padj < 0.0001).

Figure 21.

Effect of French Score on rating per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

French Score and Trial Number did not interact significantly in the Standard_Fr condition (β = 0.13, SE = 0.09, z = 1.29, p = 0.2), showing that an increasing French Score in participants did not lead to increasing ratings over the course of the task. Interestingly, the effect of this interaction was shown to be significantly different for the Innov_Engl condition (β = −0.32, SE = 0.15, z = −2.17, p = 0.03). Again, we releveled the model to obtain the exact effect of the interaction within the Innov_Engl condition, but it was shown to be non-significant (β = −0.19, SE = 0.11, z = −1.77, padj = 0.2).

3.4.2. Response Times

Log-transformed response times (RTs) in object clitic items were analyzed using the linear mixed model in (8):

- (8)

- Log RT ~ Condition + French Score + Trial Number + Condition: French Score + Condition: Trial Number + French Score: Trial Number + Condition: French Score: Trial Number + (1 + Condition + Trial Number | Participant) + (1 | Item)

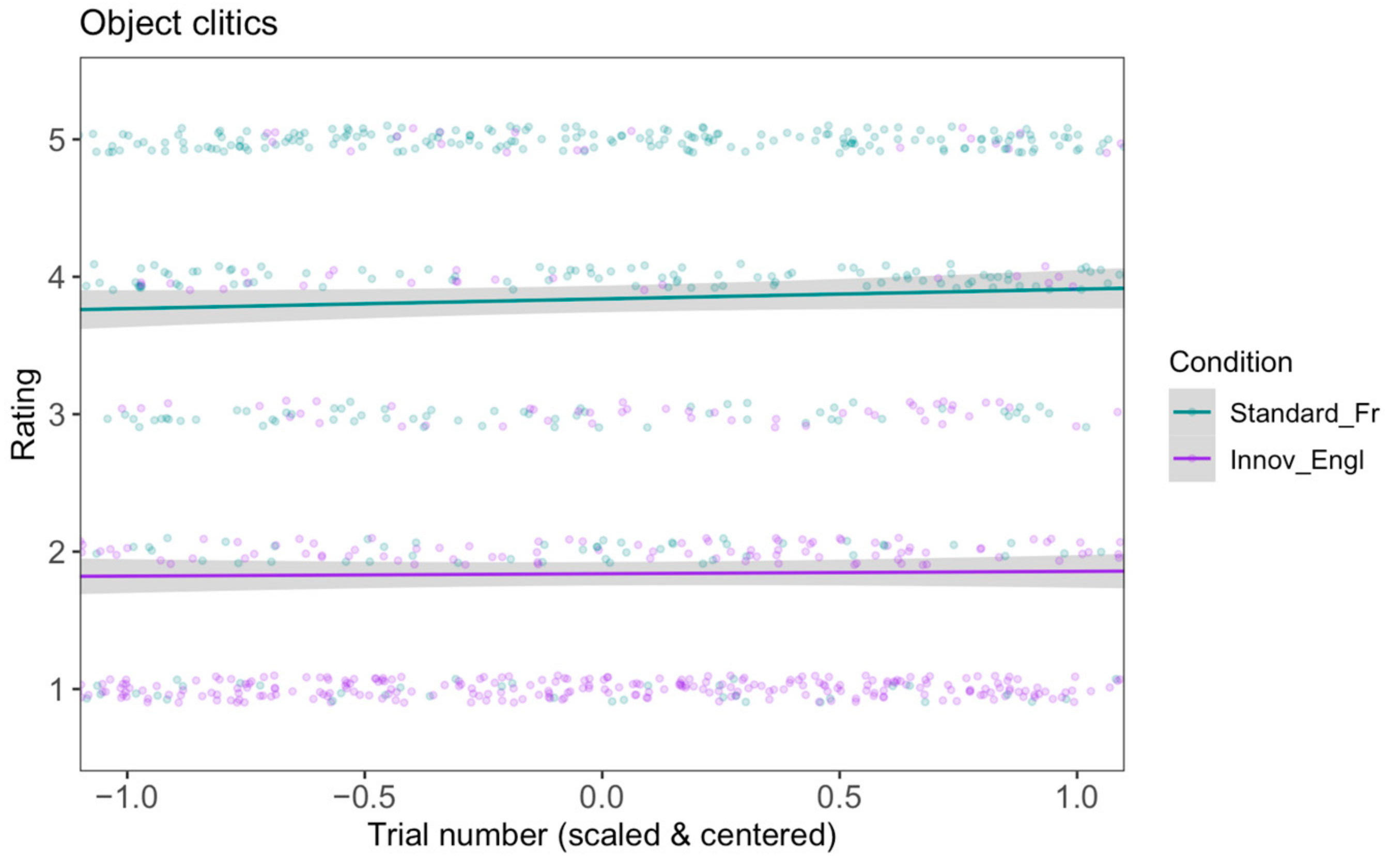

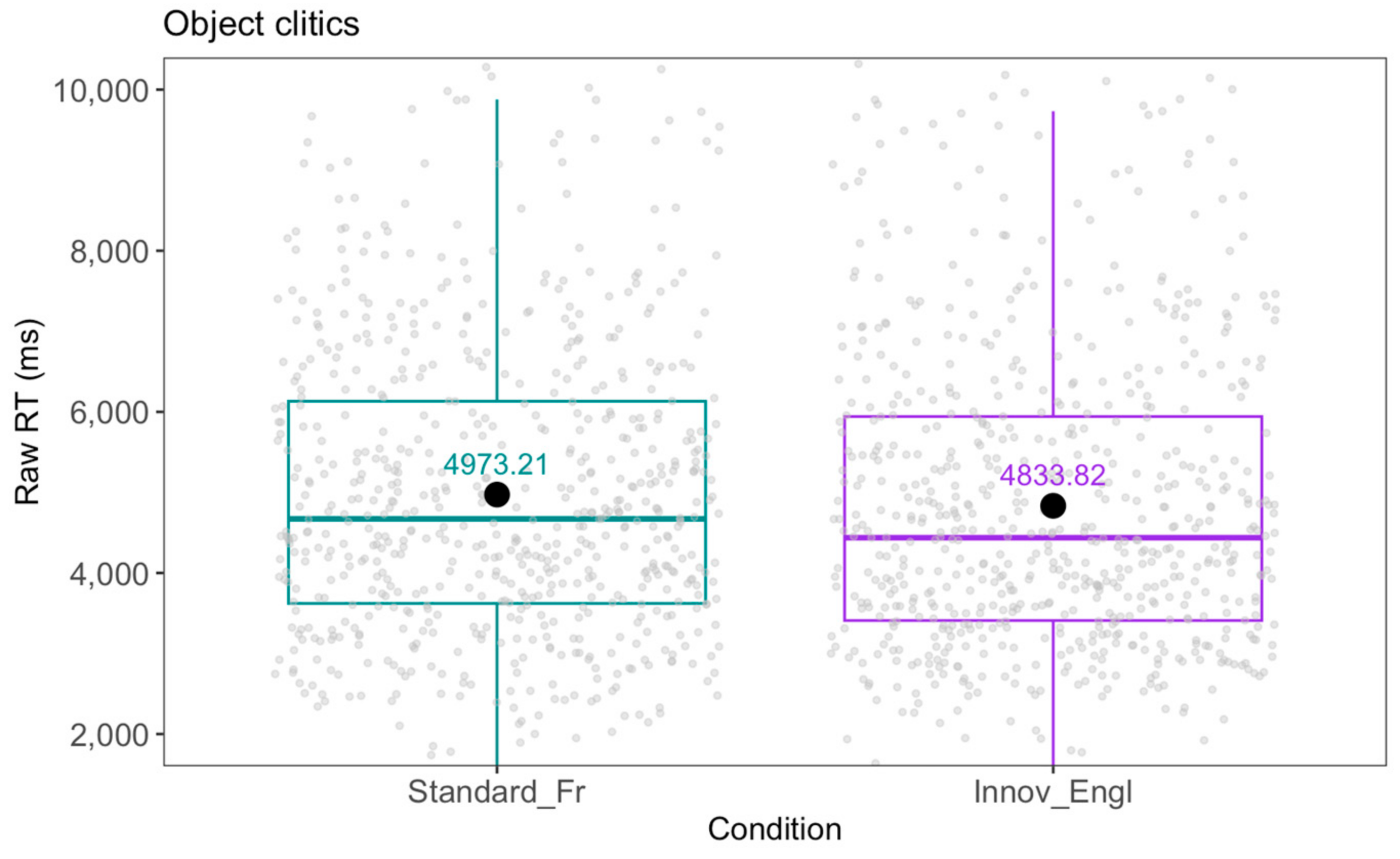

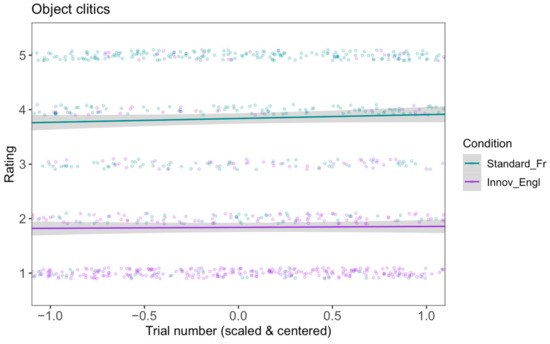

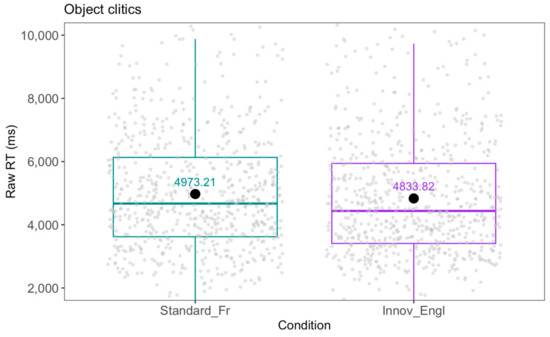

Unlike in the other structures, participants did not rate the Standard_Fr object clitic sentences significantly faster than the Innov_Engl ones (β = −0.03, SE = 0.02, t = −1.49, p = 0.1) (Figure 22).

Figure 22.

Distribution of individual raw RTs (gray dots) within the two conditions. The bold horizontal line in each box is the median RT per condition. The black dot is the mean RT (indicated as text).

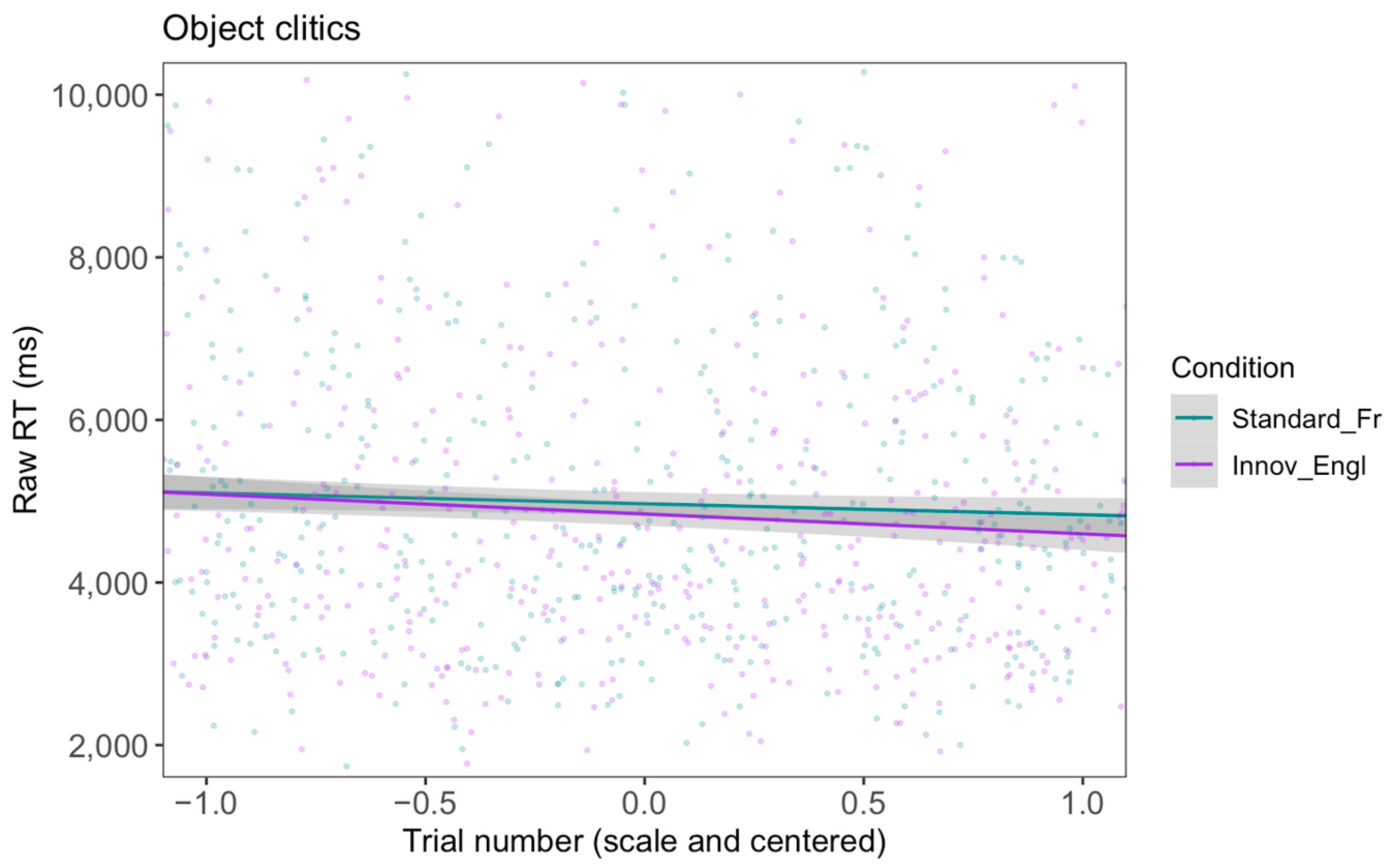

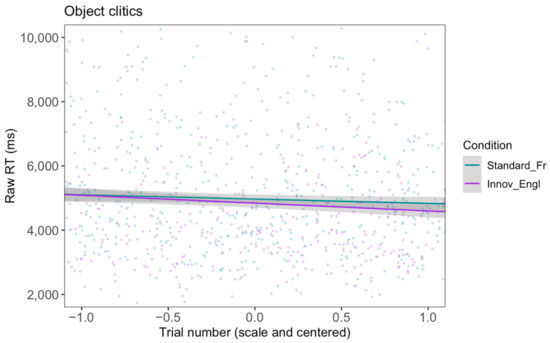

An increasing Trial Number (Figure 23) led, again, to lower RTs in the Standard_Fr condition (β = −0.06, SE = 0.01, t = −4.79, p < 0.0001). The interaction between Trial Number and Condition indicated that the effect of Trial Number was not significantly different in the Innov_Engl condition compared to the Standard_Fr condition (β = −0.002, SE = 0.02, t = 0.12, p = 0.9).

Figure 23.

Effect of Trial Number on raw RTs per condition. The gray area around each line is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

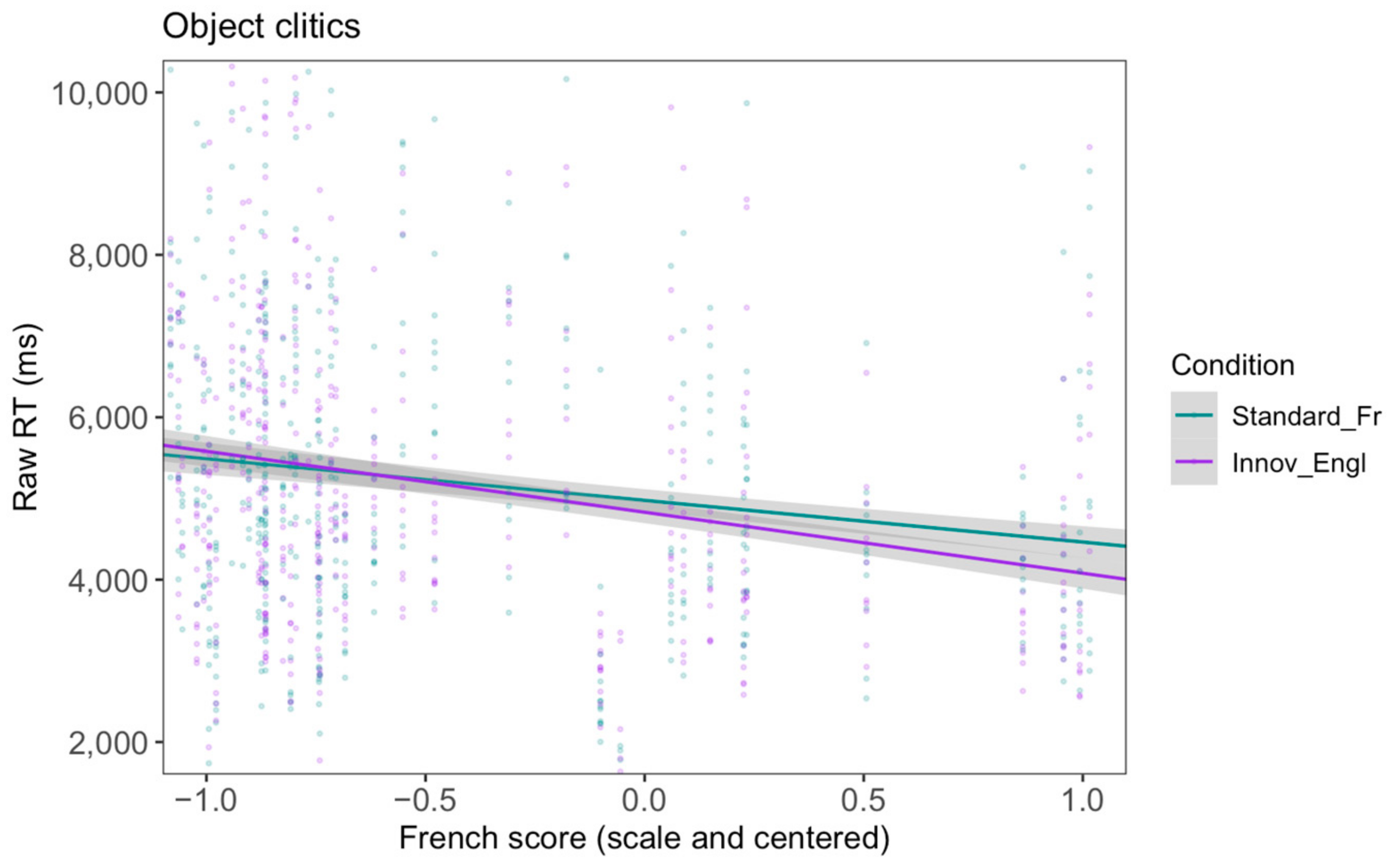

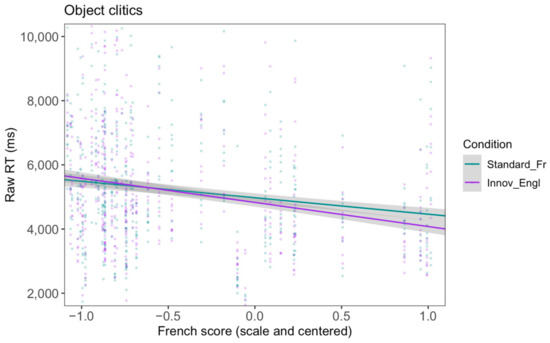

An increasing French Score in participants resulted in a significant decrease in RTs for Standard_Fr sentences (β = −0.11, SE = 0.04, t = −2.84, p = 0.001) (Figure 24). The interaction between French Score and Condition showed that the effect of French Score became more negative for Innov_Engl items than for Standard_Fr items (β = −0.05, SE = 0.02, t = −2.33, p = 0.02). The releveled model revealed a significant decrease in RTs with an increasing French Score for the Innov_Engl sentences that was stronger than for Standard_Fr sentences (β = −0.16, SE = 0.04, t = −4.19, padj = 0.0002).

Figure 24.

Effect of French Score on raw RTs per condition. The gray area around the lines is the Standard Error (SE). The dots are individual data points in the two conditions.

Moreover, the two-way interaction between French Score and Trial Number was not significant in the Standard_Fr condition, indicating that participants RTs remained stable regardless of French Score across trials (β = 0.003, SE = 0.01, t = 0.27, p = 0.8). Compared to Standard_Fr, the effect of this interaction was not significantly different for the Innov_Engl condition in the model (β = −0.004, SE = 0.02, t = −0.23, p = 0.8).

4. Discussion

This study investigated how Canadian bilingual speakers of French and English with various degrees of contact with French accept and adapt to different types of structural innovations in Canadian French. For this purpose, we conducted a timed acceptability judgment task (TAJT) where we employed both acceptability ratings (offline measure) and response times of acceptability (online measure) as a window into adaptation. The findings are discussed on the basis of the research questions provided in Section 1.3.2.

4.1. Differences in Acceptability Ratings and RTs for Innovations Across Structures

The first research question was: How do Canadian bilingual speakers of French and English accept structural innovations in French compared to the standard (grammatical) variants? Are acceptability patterns different for the different types of innovations?

Our results show that, across the four structure types tested, the standard variants, overall, yielded higher ratings than the innovations, which is in line with our predictions and previous findings in the literature (Montrul and Bowles 2009; Montrul et al. 2015; Kupisch 2012; Kupisch et al. 2014; Higby 2016; Regulez and Montrul 2023). Similarities and differences in the patterns within each type of innovation are discussed in more detail below.

In ditransitives, participants accepted PO_Can sentences (L’homme donne un cadeau à la femme ‘The man gives a present to the woman’) at ceiling and DO_Engl sentences (L’homme donne la femme un cadeau ‘The man gives the woman a present’) significantly lower (median rating 3). As predicted, ratings for PO_Scr items (L’homme donne à la femme un cadeau ‘The man gives to the woman a present’) were in-between (median rating 4) and significantly different from the other two conditions, indicating that the scrambled word order makes this structure less acceptable/natural-sounding out of context than the standard PO_Can, but more acceptable than the English-like innovation. Importantly, the two innovative conditions differed significantly from each other, with DO_Engl yielding higher ratings than DO_Nov (L’homme donne un cadeau la femme ‘The man gives a present the woman’). This aligns with earlier research showing that bilinguals differentiate between innovations with structural equivalents in the other language and innovations without equivalents (cf. Kupisch 2012; Higby 2016). Differences in ratings between conditions were partially also reflected in response latency: bilinguals rated PO_Can and DO_Nov sentences, i.e., the highest- and the lowest-rated condition, equally fast; the fast rating of DO_Nov items shows the fast rejection of the fully novel structure, which is in line with our predictions. PO_Scr and DO_Engl sentences were rated, overall, numerically slower, but only the former differed significantly from the two faster conditions.

Monotransitive innovations (Le garçon obéit le professeur ‘The boy obeys the teacher’) were rated lower (median rating 3) and, unlike ditransitives, slower than the standard variant (Le garçon obéit au professeur). Similarly, participants accepted innovative reciprocals (Les deux amis embrassent ‘The two friends hug’) significantly less than standard reciprocals (Les deux amis s’embrassent) and were also slower at doing so. An important observation is that the innovative condition here indicated the largest median rating (4) compared to the rest of the structures. This could be due to the fact that two of the verbs (se parler, s’écrire) can still be judged as highly acceptable in the absence of the reflexive se, however, with a different meaning (talking and texting other people and not each other). Indeed, after removing these two verbs, the median rating went down to 3. However, post-hoc visualizations for each verb showed that the high acceptability of structures with a missing se also applies to verbs that require the reflexive, like se disputer (to argue) or s’entendre (to get along).

As for the object clitic structure, the innovation (Il met les sur la table ‘He them puts on the table’) yielded, overall, the lowest ratings compared to the other innovations (median rating 1 and range 1–2) and it is the only case in our data where the innovation exhibited faster RTs than the standard variant Standard_Fr (Il les met sur la table). Although post-verbal clitic placement has been reported in the speech of Francophones in the US, it seems to be relatively unnatural for our bilinguals, which is probably the reason why Mougeon et al. (2005) did not find any instances in their data. A possible explanation could lie in the nature of this innovation, since it emerges via inversion instead of omission.16

Overall, it seems that not every innovation is rated in a similar way despite the fact that all of them have an English equivalent. The structures that we tested here can be put on a continuum of acceptability that might hold for other linguistic processes as well, like production or online processing (cf. Carando 2015).

4.2. Adaptation to Different Types of Innovations Across Trials

Our second research question was: Do bilingual speakers show adaptation to innovations over the course of the task? Is adaptation different for the different types of innovations?