New Approaches to Spanish Dialectal Grammar: Guest Editor’s Introduction

1. Introduction

- Native L1 varieties. Speakers have an intranational speech community. There is one international Spanish and 20 “colonial” varieties.

- Native L1 varieties in contact with other varieties of different (Castilian) Spanish dialects.

- Native L1 varieties in contact with other European languages (e.g., English, French and Portuguese).

- Bilingual varieties. Bilingual speakers learn Spanish as an additional language on top of their mother tongue or symmetrically (e.g., Catalan–Valencian, Galician and Basque).

- Indigenized L2 varieties. These varieties are in contact with indigenous languages in America (Nahuatl, Maya, Quechua, Aimara, Guarani, Mapudungun, etc.).

- Pidgin and creole languages based on a particular lexifier (e.g., Chabacano, Palenquero, Jopará, Bozal and Papiamento).

2. Vernacular Universals and More

- The candidate feature should be attested in a vast majority (>80–90%) of a given language’s vernacular varieties.

- The candidate feature should not be patterned geographically or according to variety type (L1, L2, or pidgins/creoles).

- For the sake of crosslinguistic validity, the candidate feature should not be tied to a given language’s typological make-up: inflectional (e.g., Hungarian), isolating (Vietnamese), etc. If it is, vernacular typoversal is the more appropriate term.

- The candidate feature should be crosslinguistically attested in a significant number of the world’s languages (especially in those without a literary/philosophical tradition).

- They can be registered in all kinds of varieties: rural dialects, children’s speech, creole languages and the interlanguage of non-native speakers (hence their “universality”).

- They are documented in most vernacular varieties (although with different percentages).

- They are not modeled geographically (diatopically) or according to the type of variety.

- They have interlinguistic validity, and they are not linked to the typology of Spanish (inflection not exclusive to this language).

- They appear in other languages at the interlingual level.

- They arise naturally, as a result of basic principles of language processing, and are not learned (they depend on the input), compared to many standard traits that are usually the result of standardization or selection and are formally learned.

- They can serve as indicators of linguistic diffusion and (social) extension.

- In some cases, they can overcome the “transfer/retention” dichotomy, as well as the “conservation/innovation” dichotomy, as they are old and modern forms at the same time.

- Between vernacular universals and contact-induced change, there would be a continuum; not everything has to be a “vernacular universal” or “contact-induced change”.

- Vernacular universals: features that are common to spoken vernaculars.

- Areoversals: features common in languages or language varieties which are in geographical proximity.

- L(anguage)-versals: features that tend to recur in vernacular varieties of a specific language, such as (vernacular) Angloversals, Francoversals, etc.

- Varioversals: features recurrent in language varieties with a similar sociohistory, historical depth and mode of acquisition.

- Typoversals: features that are common to languages of a specific typological type.

- Phyloversals: features that are shared by a family of genetically related languages.

3. Dialectal Variation in Spanish: Some Features

- Conjugation regularization, or the levelling of irregular verb forms;

- Default singulars, or the subject–verb non-concord;

- Multiple negation, or negative concord;

- Copula absence, or copula deletion;

- Lack of inversion in main clause sí/no questions;

- Yo/tú instead of mí/ti in coordinate subjects;

- Adverbs taking the same form as adjectives;

- Absence of plural marking after measure nouns;

- Lack of inversion and lack of auxiliaries in qu- questions;

- Degree modifier adverbs lack -mente;

- Special forms or phrases for the second-person plural pronoun;

- Levelling of difference between tenses;

- Double comparatives and superlatives;

- Irregular use of articles;

- Levelling of preterit/past participle verb forms: regularization of irregular verb paradigm;

- Lack of number distinction in reflexives.

- Pronouns, pronoun exchange and pronominal gender;

- NP;

- Verb phrase: tense and aspect;

- Modals;

- Verb morphology;

- Adverbs;

- Negation;

- Agreement;

- Relativization;

- Complementation: “para + infinitive”; comparative clauses “contra más”;

- Discourse organization and word order.

4. On Late Insertion

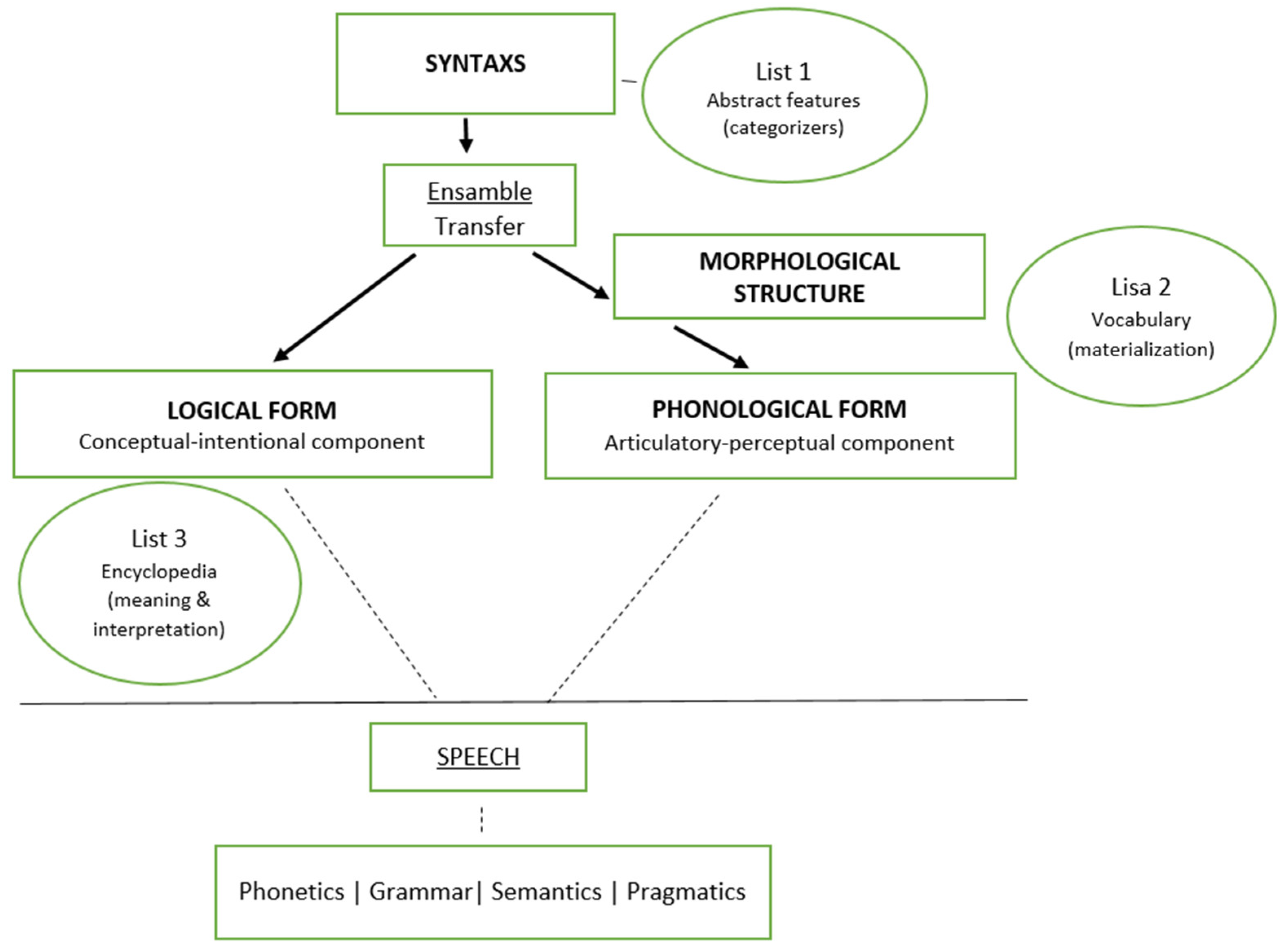

- List 1: Abstract features, roots and categorizers (nominal, verbal and adjectival), without phonological content and proper to a Language or Variety ([Plural], [Human], [Future]). Syntax does not manipulate phonological material. Located in Syntax.

- List 2: Vocabulary items. Allows abstract information [features] to be materialized/pronounced (with phonological content) in the nuclei of syntactic projections (or nodes, via the Subset Principle). Located in the Phonological Form.

- List 3: Encyclopedia. Information related to meaning and interpretation (in a given context). Located in the Logical Form.

5. Individual Contributions to This Special Issue

- 1

- María Mare. The author examines the distribution of the “genitive” pronoun in non-nominal domains (i.e., adverbial, verbal and adjectival) from a neo-constructionist approach (the late insertion of phonological exponents) and explains the complementary distribution between agreement/nominal morphology. Both the synthetic (nuestro “our”) ant the analytic (de nosotros “of us”) options may have the same syntactic structure; the difference is the nature of the nominalizer’s phi features. When the nominalizer cannot value its features, a “non-genitive” pronoun (nosotros) lexicalizes the pronominal structure, and the head p/Place is lexicalized by de.

- 2

- Bruno Camus Bergareche. The author presents a detailed description of some morphological and syntactical phenomena distributed in Castile–La Mancha that are actually documented in a general way (leísmo and laísmo; deísmo; non-standard clitic sequences me se; transitive use of entrar, caer and quedar; reduced desinence for second person plural verb forms like cogís instead of cogéis; etc.) and that show its internal boundaries. This dialectal description helps to know this variety better and not to classify it simply as “transitional” between northern and southern Spanish.

- 3

- Luis Eguren and Cristina Sánchez López. The “Expletive” mismo (“same”) is a non-comparative emphatic use of this prenominal adjective in many American Spanish varieties (Finalmente, Laura se sentó y aceptó el cigarrillo, mismo que nunca encendió “Laura finally sat down and accepted the cigarette, same that she never lighted up”). The authors provide its geographical distribution and a novel analysis of its properties. They conclude that mismo functions as an anaphoric “reinforcer” preceded by a null definite determiner and combines with an empty noun that takes a restrictive relative clause (que).

- 4

- Teresa María Rodríguez Ramalle. This paper studies the variation found in some discursive structures and compares the use of que with evidential adverbs (naturalmente “naturally”, ciertamente “certainly”) and affirmative adverb sí (que) in Latin American Spanish. The proposal is that evidential adverbs are examples of recomplementation.

- 5

- Elena Felíu Arquiola. This paper studies a syntactic construction with a verb in a non-pronominal intransitive variant (congela “freeze”) with property interpretation (La masa de pizza congela perfectamente “Pizza dough freezes perfectly”, instead of se congela). The author pays special attention to the type of verb and establishes a comparison with mediopassive and anticausative constructions. Linguistic factors (the presence of a manner adverb and negation) as well as extralinguistic factors (the type of text and geographical distribution) are also reviewed.

- 6

- José Silva Garcés and Gonzalo Espinosa. They describe the prosodic, semantic and morphosyntactic behaviour of duplicated verbs surrounding an XP that bears the nuclear accent of the phrase (Se fueron por Bariloche, se fueron “They went by Bariloche, they went”) in Patagonian Spanish and propose a biclausal analysis in which each duplicate originates in a different clause (CP1 and CP2). In this case, the structure moves to the left periphery of CP2.

- 7

- Florencio del Barrio de la Rosa. Spanish nouns vary depending on their denotation (niño “male child”/niña “female child”), and when lacking an inflectional cue, they could assume both genders (azúcar moreno “brown sugar”/azúcar blanquilla “white sugar”). This study addresses the socio-geographical factors conditioning gender assignment in European Spanish and shows how gender values are determined and diffused across rural and urban varieties.

- 8

- Sara Gómez Seibane. Clitic doubling (i.e., the co-appearance of a clitic and a correlative syntagma) is an internal/external language interface phenomenon. This study determines the frequency of this use and analyses the following features: definiteness, specificity, the cliticization of direct object, and the accessibility of IO referents in the minds of the speakers.

- 9

- Juan José Arias. This study, within the framework of Distributed Morphology, explores the exclamative use of the feminine definite article la (¡La de chicos que besé en la fiesta! “How many guys I kissed at the party!”). According to the author, this kind of example is not CP but indefinite DP with an exclamative behaviour, which contain a pseudo-relative clause with que. The DP projections (FocP and FinP) allow la to move to Spec-FocP and be interpreted as an exclamative operator.

- 10

- Edita Gutiérrez-Rodríguez and Pilar Pérez Ocón. This paper offers a formal analysis for deísmo (i.e., the insertion of preposition de (“of”) before an infinitive clause: Me apetece de salir “I want to go out”). The authors propose that this preposition (de) is located in a projection below that of the de in dequeísmo constructions (Creo de que hay tiempo suficiente “I believe there is enough time”). Moreover, deísmo is lexically associated with certain verbs but not with a semantic class. Finally, they propose that there is not an evidential meaning associated with deísmo.

- 11

- Jorge Agulló. Unlike Catalan, existential constructions in Spanish are sensitive to definiteness or quantification restriction. This fact prevents personal pronouns (*Había él en la habitación “There was him in the room”), proper nouns (*Hay Inés en la habitación “There is Inés in the room”) and definite constituents (*Hay tu libro en la habitación “There is your book in the room”) from occupying the pivot position. In contrast, contact varieties between Spanish and Catalan show a range of examples not yet analyzed. The author quantitatively studies the variation between definite and indefinite pivots in both languages, and offers a new explanation based on the person, number and gender (phi features) of the pivot (haber).

- 12

- Avel·lina Suñer Gratacós. This paper, using a compositional approach, analyzes immediate succession subordinators in temporal subordinates, its different materialized forms and its patterns. She concludes that new subordinators can be created by adding a component [immediacy] to a previously temporal subordinator.

- 13

- Aldo Olate and Ricardo Pineda. The authors analyze and compare the nominal possessive constructions (Su casa de Pedro “His house of Pedro”) in bilingual Mapudungun/rural Spanish and monolingual rural and urban Spanish. They show this use of copying as a strategy of the speakers and its communicative needs.

- 14

- Silvia Gumiel-Molina, Norberto Moreno-Quibén and Isabel Pérez-Jiménez. In innovative uses of estar (Voy a visitar usuarios que están muy morosos “I am going to visit users that are defaulting debtors”), there is no comparison between stages or counterparts of the subject (usuarios) and the property expressed by the adjective (morosos). This study provides a complete characterization of this use, shows its geographical distribution and reviews the lexical–syntactic classes of adjectives that appear in it.

- 15

- Grant Armstrong. Yucatec Spanish exhibits a syntactic construction between an impersonal and passive (Te castigaron por mi tío “You were punished by my uncle”), where the preposition por introduces an agent, the verb is third person plural (castigaron) and an accusative clitic (te) is possible. Labeled as Active–Passive hybrid, the author formally analyzes these hybrid constructions and arges that they are instances of grammatical object passives. The emergence of a null pronoun in the specifier of Voice restricts an agent argument and allows for this type of sentence. In addition, language contact may have played a role in this case.

- 16

- Ignacio Bosque. This author analyzes four vernacular interpretations of the adverb siempre (“always”): (i) continuative, (ii) progressive–comparative (in Rioplatense Spanish), (iii) concessive–adversative (in Mexico and Central America) and (iv) attenuated (in Andean Spanish). He also offers an interpretation of this adverb as a universal quantifier with different semantic nature.

6. Final Remarks

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adger, David, and Jennifer Smith. 2010. Variation in agreement: A lexical feature-based approach. Lingua 120: 1109–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Mark. 2008. The Macroparameter in a Microparametric World. In The Limits of Syntactic Variation. Edited by Theresa Biberauer. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 351–73. [Google Scholar]

- Borer, Hagit. 1984. Parametric Syntax. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Bosque, Ignacio. 2023. Aspectos didácticos de la variación gramatical. Asterisco 1: 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosque, Ignacio, and Javier Gutiérrez-Rexach. 2009. Fundamentos de sintaxis formal. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Jack K. 2004. Dynamic typology and vernacular universals. In Dialectology Meets Typology. Dialect Grammar from a Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Edited by Bernd Kortmann. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 127–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on Government and Binding. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, David. 2004. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Di Tullio, Ángela, and Enrique Pato. 2022. Universales vernáculos en la gramática del español. Madrid and Frankfurt: Iberoamericana/Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Eguren, Luis. 2014. La Gramática Universal en el Programa Minimista. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada 52: 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed Morphology and the Pieces of Inflection. In The View from Building 20: Essays in Linguistics in Honor of Sylvain Bromberger. Edited by Ken Hale and S. Jay Keyser. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 111–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kortmann, Bernd. 2004. Dialectology Meets Typology. Dialect Grammar from a Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kortmann, Bernd, and Benedikt Szmrecsanyi. 2007. The Quest for Vernacular Universals and Angloversals: Evidence from the “World Atlas of Morphosyntactic Variation in English”. Nijmegen: LOT Winter School, January 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kroch, Anthony. 2001. Syntactic change. In The Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theories. Edited by Mark Baltin and Chris Collins. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 699–729. [Google Scholar]

- Kusters, Wouter. 2003. Linguistic Complexity: The Influence of Social Change on Verbal Inflection. Leiden: Leiden University. [Google Scholar]

- Mare, María. 2015. Proyecciones funcionales en el ámbito nominal y concordancia: Un abordaje en términos de variación. Munich: Lincom. [Google Scholar]

- Mare, María. 2023. Morfología Distribuida desde el sur del Sur. Quintú Quimün. Revista de Lingüística 7: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne, John, and Peter Kleiweg. 2007. Toward a Dialectological Yardstick. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 14: 148–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Michel. 2004. A Neurolinguistic Theory of Bilingualism. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pato, Enrique. 2023. Los universales vernáculos y la inserción tardía en el estudio de la variación. In VII Encuentro sobre dialectos del español (SpaDiSyn). Invited speaker. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid, November 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ranta, Elina. 2022. From learners to users—errors, innovations, and universals. ELT Journal 76: 311–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmrecsanyi, Benedikt, and Bernd Kortmann. 2009. Vernacular Universals and Angloversals in a Typological Perspective. In Vernacular Universals and Language Contacts: Evidence from Varieties of English and Beyond. Edited by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola and Heli Paulasto. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Szmrecsanyi, Benedikt, and Melanie Röthlisberger. 2019. World Englishes from the perspective of Dialect typology. In The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Edited by Daniel Schreier, Marianne Hundt and Edgar W. Schneider. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 534–58. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, Peter. 2010. Contact and Sociolinguistic typology. In The Handbook of Language Contact. Edited by Raymond Hickey. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 299–319. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pato, E. New Approaches to Spanish Dialectal Grammar: Guest Editor’s Introduction. Languages 2024, 9, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9020036

Pato E. New Approaches to Spanish Dialectal Grammar: Guest Editor’s Introduction. Languages. 2024; 9(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9020036

Chicago/Turabian StylePato, Enrique. 2024. "New Approaches to Spanish Dialectal Grammar: Guest Editor’s Introduction" Languages 9, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9020036

APA StylePato, E. (2024). New Approaches to Spanish Dialectal Grammar: Guest Editor’s Introduction. Languages, 9(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9020036