Abstract

Pharmacies in Bulgaria have a monopoly on the dispensing of medicinal products that are authorized in the Republic of Bulgaria, as well as medical devices, food additives, cosmetics, and sanitary/hygienic articles. Aptekari (pharmacists) act as responsible pharmacists, pharmacy owners, and managers. They follow a five year Masters of Science in Pharmacy (M.Sc. Pharm.) degree course with a six month traineeship. Pomoshnik-farmacevti (assistant pharmacists) follow a three year degree with a six month traineeship. They can prepare medicines and dispense OTC medicines under the supervision of a pharmacist. The first and second year of the M.Sc. Pharm. degree are devoted to chemical sciences, mathematics, botany and medical sciences. Years three and four center on pharmaceutical technology, pharmacology, pharmacognosy, pharmaco-economics, and social pharmacy, while year five focuses on pharmaceutical care, patient counselling, pharmacotherapy, and medical sciences. A six month traineeship finishes the fifth year together with redaction of a master thesis, and the four state examinations with which university studies end. Industrial pharmacy and clinical (hospital) pharmacy practice are integrated disciplines in some Bulgarian higher education institutions such as the Faculty of Pharmacy of the Medical University of Sofia. Pharmacy practice and education in Bulgaria are organized in a fashion very similar to that in most member states of the European Union.

1. Introduction

Concerning general health in Bulgaria, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that a person born in Bulgaria in 2016 can expect to live 74.6 years on average: 78 years if female and 71.2 years if male (Table 1). WHO also estimated that life expectancy at birth for both sexes increased by 3 years over the period of 2000–2012; the WHO regional average increased by 4 years in the same period. In 2012, healthy life expectancy, in both sexes, was 9 years lower than the European average. This lost healthy life expectancy represents 9 equivalent years of full health lost through years lived with morbidity and disability.

Table 1.

Health statistics for Bulgaria [1].

Despite these somewhat disappointing figures, progress has been made in the past 30 years. Since the disruption of the established order of the Soviet Union in 1989, the on-going economic, political, and social changes in Bulgaria have had an important impact on all aspects of social life in the country, including pharmaceutical activities. Until 1989, the pharmaceutical system was centralized—community pharmacies, hospital pharmacies, wholesalers, pharmaceutical factories, and institutes were owned by the state. The importation and exportation of drugs were controlled by the state.

Following the changes in 1989, the Bulgarian pharmaceutical system is oriented towards the private sector. Community pharmacies, wholesalers, and many drug manufacturers are now private entities. The first Bulgarian Law on drugs and pharmacies in human medicine was introduced in 1995 [2]. It lays out the structure for harmonization of Bulgarian drug regulatory affairs with those of the European Union.

All these specific circumstances, together with a more global perspective on new drug discoveries and pharmaceutical technologies and methodologies, are a constant challenge leading to re-evaluation of the role of pharmacists in the Bulgarian health care system. Before these changes, a majority of Bulgarian pharmacists’ time was spent manufacturing drugs in the pharmacy. Nowadays, pharmacists apply different skills that require a detailed knowledge of communications and human behavior to scientifically dispense medications, and to counsel patients about their health and the correct use of their prescribed and OTC drugs. They are also responsible for monitoring patients to avoid adverse drug reactions and to achieve maximum benefit from the treatment. A very recent development is the implementation of the concept of “pharmaceutical care” as a central element of pharmacy practice.

The Medical University in Sofia will be taken as an example for Bulgaria. The university has four faculties: medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, and social health. The pharmacy faculty is the oldest in Bulgaria in educating pharmaceutical specialists. The duration of the education is five years for community, hospital, and industrial pharmacists. All the graduates receive a M.Sc. Pharm. degree. One hundred to 120 Bulgarian and 80–100 foreign students are accepted for pharmacy education and training every year.

There are six departments in the Faculty of Pharmacy in the Medical University in Sofia:

- Pharmaceutical Technology and Bio-Pharmacy

- Pharmacognosy and Pharmaceutical Botany

- Pharmaceutical Chemistry

- Chemistry

- Pharmacology and Toxicology

- Social Pharmacy

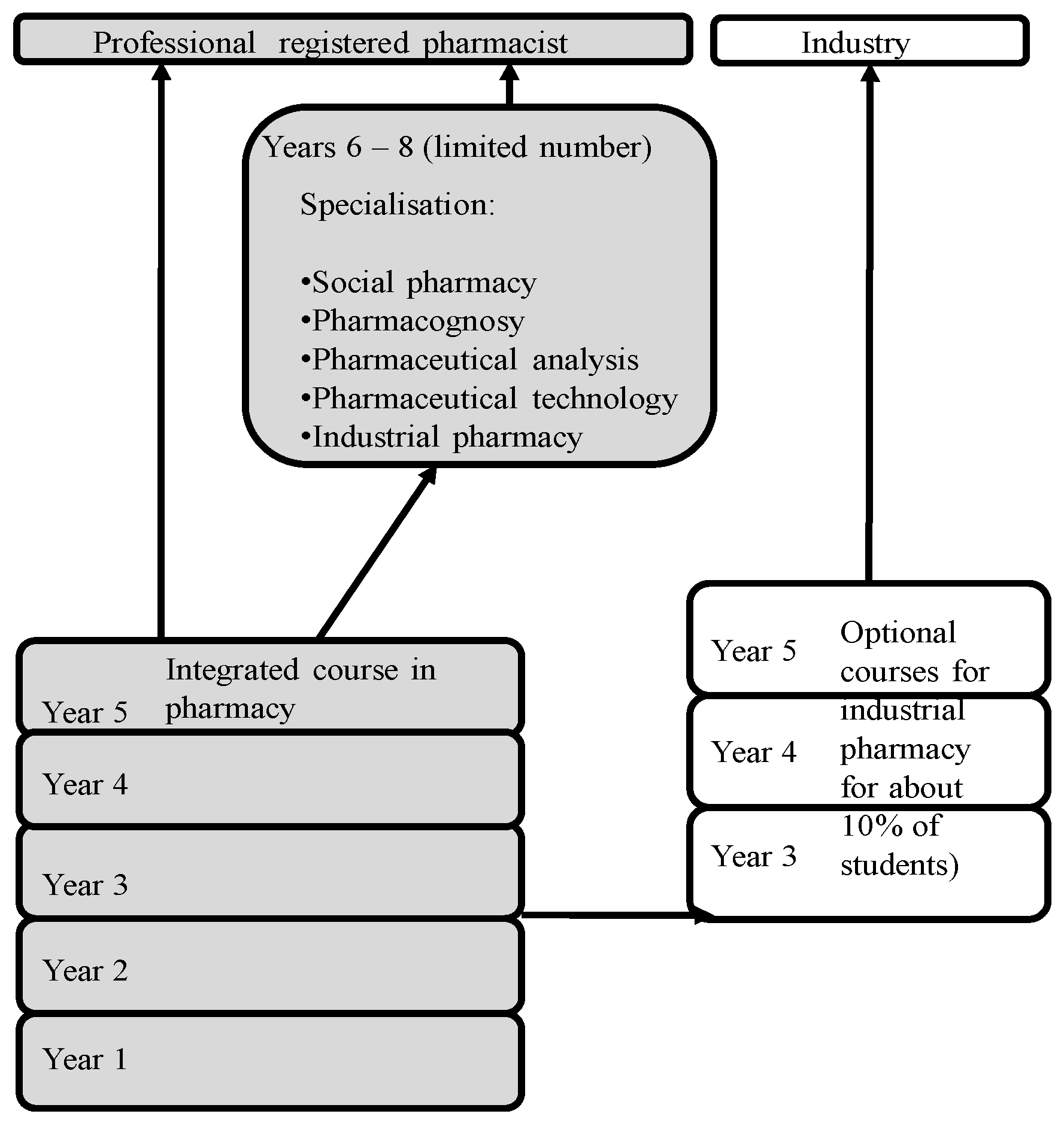

Following graduation, students have the opportunity to specialize for a further 3 years. Whilst working in a hospital or industrial environment, they follow a study program with courses at the faculty of pharmacy two weeks per year. After the third year of such specialization they pass a state examination in a given specialty. This possibility is granted by the Ministry of Education to all pharmaceutical students and graduates.

Since 1989, there have been many changes in the curriculum to harmonize courses and diplomas with those of the other schools in the European Union (EU). Many new study areas have been introduced such as: bio-pharmacy, clinical laboratory testing and analysis, and biology. The Department of Social Pharmacy has introduced new study areas such as: history of pharmacy, pharmaco-epidemiology, pharmaco-economics, pharmaceutical law, pharmaceutical marketing, and pharmaceutical management.

In 2000, a new course in pharmaceutical care was introduced. The lectures and seminars on this subject are given during the first semester of the fifth year. The lectures synthesize the knowledge gained during the five-year pharmacy course and blend this with communication skills and the development of the logic of pharmaceutical care. University lecturers together with pharmacy practitioners, provide the training.

2. Design

Given the changes in pharmacy practice and education in Bulgaria outlined above, the PHARMINE (Pharmacy Education in Europe) European consortium surveyed the state of pharmacy education and practice in Bulgaria in 2012, with an update in 2017. The PHARMINE consortium was interested in general practice and education and in specialization in pharmacy education for hospital and industrial pharmacy practice. The survey also looked at the impact of the Bologna agreement on harmonization of the various European degree courses [3], and on the directive of the European Commission on education and training for the sectoral profession of pharmacy [4]. These two documents are somewhat contradictory in that the Bologna agreement proposes a bachelor plus master degree structure for all degrees including pharmacy, whereas as the European directive lays down a five-year “tunnel” degree structure for pharmacy, i.e., a degree course that has no possibility for intermediate entry or exit for example after a three-year bachelor period. The methodology used in the PHARMINE survey [5] and the principal results obtained in the EU [6] have already been published.

3. Evaluation and Assessment

3.1. Organisation of the Activities of Pharmacists, Professional Bodies

Table 2 provides details of the numbers and activities of community pharmacists and pharmacies in Bulgaria.

Table 2.

Numbers and activities of community pharmacists and pharmacies.

The data in Table 2 shows that compared to the EU linear regression estimation (for definition and calculation see reference 5) the ratio of the actual number of community pharmacists in Bulgaria (/population) compared to the linear regression estimation for Bulgaria = 1.16. Thus number of pharmacists per population is very close to the EU norm. The same comparison for community pharmacies produces a ratio of 1.99. Thus the number of community pharmacies in Bulgaria is double the EU average.

The activities and occupations of pharmacists in Bulgaria are similar to those of community pharmacists in other member states [5]. The organization of community pharmacists regarding ownership, etc. is similar to that elsewhere in the EU; it should be noted that there are no government-imposed rules on the geographical distribution of community pharmacies in Bulgaria. The sale of medicinal products on the internet is limited to authorized pharmacies.

Table 3 provides details of the numbers and activities of assistant pharmacists in Bulgaria.

Table 3.

Numbers and activities of assistant pharmacists.

Bulgarian legislation recognizes that assistant pharmacists are health care professionals and defines their role in the health care system. Five pharmaceutical colleges provide education and training for assistant pharmacists. Although this is in the form of a three-year course, it cannot be compared to a “B. Pharm.” as defined by the Bologna declaration (see above).

Table 4 provides details of the numbers and activities of hospital pharmacists in Bulgaria.

Table 4.

Numbers and activities of hospital pharmacists.

Bulgarian legislation recognizes the existence of a hospital pharmacy, although the number of hospital pharmacists is low compared to the EU average. The ratio of the actual number of hospital pharmacists in Bulgaria (/population) compared to the linear regression estimation for Bulgaria = 0.29, (for definition and calculation see reference 5). The estimated number of hospital pharmacies is higher than that of hospital pharmacists. It appears therefore that the function of “hospital pharmacist” in Bulgaria is defined by competences and roles and/or by place of work. In the latter case, health care personnel other than pharmacists are involved.

Table 5 provides details of the numbers and activities of industrial pharmacists and pharmacists in other sectors, in Bulgaria.

Table 5.

Numbers and activities of industrial pharmacists and pharmacists in other sectors.

Industrial pharmacists in Bulgaria have similar practices and duties to those in other EU countries [5]. As numbers of industrial pharmacists were not available for most European countries a comparison with the EU average is not possible.

Table 6 provides information on professional associations for pharmacists in Bulgaria.

Table 6.

Professional associations for pharmacists in Bulgaria.

The Bulgarian pharmaceutical union, which is the representative organisation of pharmacists in the country, oversees pharmacy education and training (PET), pharmacy practice, and ethics in a fashion similar to that in other member states of the EU [5].

3.2. Pharmacy Faculties, Students, and Courses

Table 7 provides details of pharmacy higher education institutions (HEIs), staff and students in Bulgaria.

Table 7.

Pharmacy higher education institutions (HEIs), staff, and students in Bulgaria.

The ratios of the actual number of HEIs, staff, and students in Bulgaria (/population) compared to the linear regression estimations for Bulgaria are 1.07, 1.01, and 0.76, respectively (for definition and calculation see reference [5]). Thus, figures for Bulgarian PET reflect those of the EU average for the country with a population the size of that of Bulgaria. Student numbers show a substantial international intake. It should be noted that the Erasmus Programme (European Region Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students) is an EU student exchange program. Table 8 provides details of specialization electives in pharmacy HEIs.

Table 8.

Specialization electives in pharmacy HEIs.

Both pre- and post-graduate specialization are possible in Bulgaria. The last wave of pharmacists in post-graduate specialization in the medical university of Sofia was composed as follows—social pharmacy: 25; pharmacognosy: one; pharmaceutical analysis: one; pharmaceutical technology: one; industrial pharmacy: three. In this context, social pharmacy can be considered to consist of all the social factors that influence medicine use.

Table 9 provides details of past and present changes in education and training in Bulgarian pharmacy HEIs.

Table 9.

Past and present changes in education and training in Bulgarian pharmacy HEIs.

3.3. Teaching and Learning Methods

Table 10 provides details of student hours [18] by learning method. The data from Sofia is taken as an example in this table and Table 11.

Table 10.

Student hours by learning method.

Table 11.

Student hours by subject area (for definition of subject areas see [4]). The numbers are calculated according to the schema of the Uniform State Requirements of Bulgaria [14].

Regarding the validation of traineeship, the pharmacist responsible for the trainee fills in a monthly and a final report at the end of the six months and these are validated (or not) by the HEI. It is to be noted that “practical” work is carried out by students at the university in the form of personnel projects, etc., whereas “traineeship” refers to work in a pharmacy setting.

3.4. Subject Areas.

Table 11 provides details of student hours by subject area.

3.5. Impact of the Bologna Principles [3]

Table 12 provides details the various ways in which the Bologna declaration impacts on Bulgarian pharmacy HEIs.

Table 12.

Ways in which the Bologna declaration impacts on Bulgarian pharmacy HEIs.

Data in the above table are in exchange months per year. The faculty of pharmacy in Sofia has ERASMUS exchange programs with:

- ○

- Belgium, University of Antwerp and Vrije Universiteit Brussels

- ○

- France, Université de Lorraine, Nancy and Université de Limoges

- ○

- Germany, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Anhalt University of Applied Sciences Kothen and Freie Universität Berlin

- ○

- Czech Republic—University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Brno

- ○

- Italy—Universita’ degli studi di Siena and Sapienza, University of Rome

- ○

- Spain—University of Navarra and Universitat autonoma de Barcelona

There is also an exchange program with Turkey—Mersin University.

3.6. Impact of EU Directive 2013/55/EC

Table 13 provides details the various ways in which the EC directive impacts on Bulgarian pharmacy HEIs [3].

Table 13.

Ways (right column) in which the elements of the EC directive (left column) impact on Bulgarian pharmacy HEIs.

Bulgarian PET mainly conforms to the different aspects of the EC directive with notably a five-year tunnel degree. Aspects of the Bologna agreement such as European Credit Transfer System (ECTS) and the Diploma Supplement are included.

Figure 1 shows the scheme of PET in Bulgaria.

Figure 1.

The scheme of pharmacy education and training (PET), in Bulgaria.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Pharmacies in Bulgaria have a monopoly on the dispensing of medicinal products in Bulgaria. Pharmacists follow a five-year (M.Sc. Pharm.) degree course with a six months traineeship. The first and second year of the M.Sc. Pharm. degree are devoted to chemical sciences, mathematics, botany, and medical sciences. Years three and four center on pharmaceutical technology, pharmacology, pharmacognosy, pharmaco-economics, and social pharmacy, and year five on pharmaceutical care, patient counselling, pharmacotherapy, and medical sciences. A six month traineeship finishes the fifth year together with redaction of a master thesis, and the four state examinations with which university studies end. Industrial pharmacy and clinical (hospital) pharmacy practice are integrated disciplines in some Bulgarian HEIs, such as the Faculty of Pharmacy of the Medical University of Sofia.

Following the changes in Bulgaria in 1989, pharmacy practice and education are organized in a fashion very similar to that in (most member states of) the European Union. Whilst new developments in pharmaceutical care with elements such as immunization, advice on tobacco use cessation, management of medication adherence, and provision of health screening to detect hypertension do not at the present time receive financial backing from the government, the fact that these elements are supported at the academic level, should reinforce the future role of the pharmacist in the promotion of patient well-being in Bulgaria.

Acknowledgments

Valentina BELCHEVA, Sanofi-Aventis, 103, Al. Stamboliiski Blvd.-level 8, Sofia Tower building, 1303 Sofia, Bulgaria (valentina.belcheva@sanofi-aventis.com) participated in the production of the 2012 version of this country profile. With the support of the Lifelong Learning Program of the European Union (142078-LLP-1-2008-BE-ERASMUS-ECDSP).

Author Contributions

Valentina Petkova provided all the data and information and helped in the revisions of the manuscript; Jeffrey Atkinson wrote the first manuscript and dealt with revisions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- The WHO Statistical Profile of Bulgaria. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/countries/bgr.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Bulgarian Law on Drugs and Pharmacies in Human Medicine. Available online: http://www.zdrave.net/document/institute/e-library/BG_Health_Acts/Drugs_Act.htm (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Bologna Agreement of Harmonisation of European University Degree Courses. Available online: http://www.ehea.info/ (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- The European Commission Directive on Education and Training for Sectoral Practice Such as That of Pharmacy. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/?uri=celex:32013L0055 (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Atkinson, J. The PHARMINE Survey Methodology. Submitted.

- Atkinson, J.; Rombaut, B. The 2011 PHARMINE report on pharmacy and pharmacy education in the European Union. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 9, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarian Drug Agency. Available online: http://bda.bg/bg/?lang=enimages/stories/documents/legal_acts/ZLPHM_en.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Bulgarian Assistant Pharmacists’ Code. Available online: http://old.mu-sofia.bg/index.php?p=166&l=1 (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Register of the Pharmacists of the Bulgarian Pharmaceutical Union. Available online: https://bphu.bg/19_Register.htm (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Bulgarian Branch of the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP). Available online: http://www.eahp.eu/about-us/members/bulgaria (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Bulgarian Association of Hospital Pharmacists. Available online: http://www.ohpb.org/styled/page5/index.php (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) Bulgaria. Available online: http://www.arpharm.org/en (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Association of the Research-Based Pharmaceutical Manufacturers in Bulgaria (ARPharM). Available online: www.arpharm.org/en (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA): The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures 2016. Available online: http://www.efpia.eu/publications/data-center/ (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- The Bulgarian Pharmaceutical Union Certification. Available online: http://bphu.eu/about_us.php?id_page=1 (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Quality Commission of the Bulgarian Pharmaceutical Union. Available online: https://bphu.bg/bg.htm (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Student Numbers in Bulgarian pharmacy HEIs. Available online: http://www.medfaculty. EC Directive on Sectoral Professions org/forum/index.php?action=printpage;topic=6177.0 (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Details of Courses in Sofia. Available online: http://www.pharmfac.net/course.htm (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Atkinson, J.; De Paepe, K.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. Does the Subject Content of the Pharmacy Degree Course Influence the Community Pharmacist’s Views on Competencies for Practice? Pharmacy 2015, 3, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).