CSR in Professional Football in Times of Crisis: New Ways in a Challenging New Normal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivation

2.2. Strategic

2.3. Organisational Integration

2.4. Operational

2.4.1. Implementation

2.4.2. Measurement

2.4.3. Communication

2.5. Impact of COVID-19 on Scottish Society, Football and CSR

3. Methodology

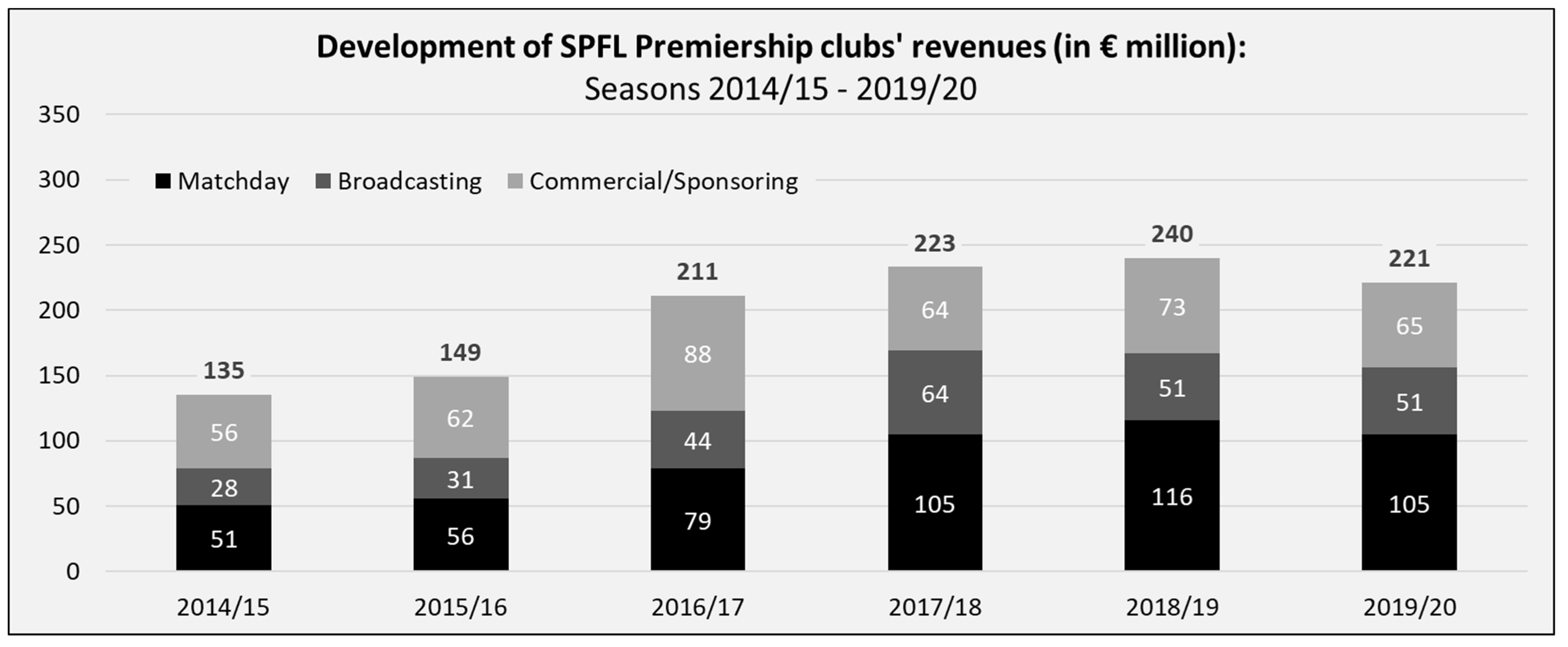

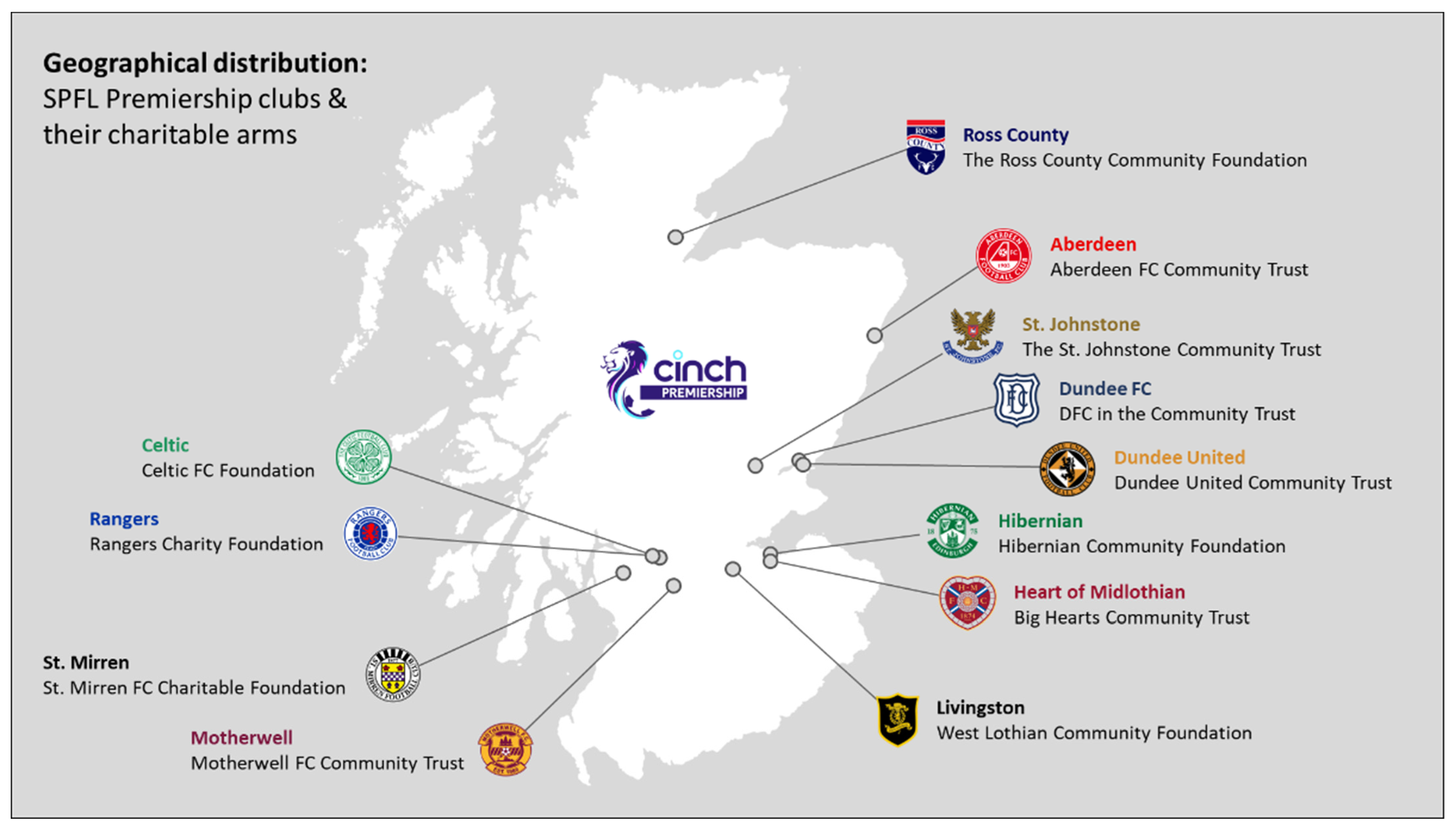

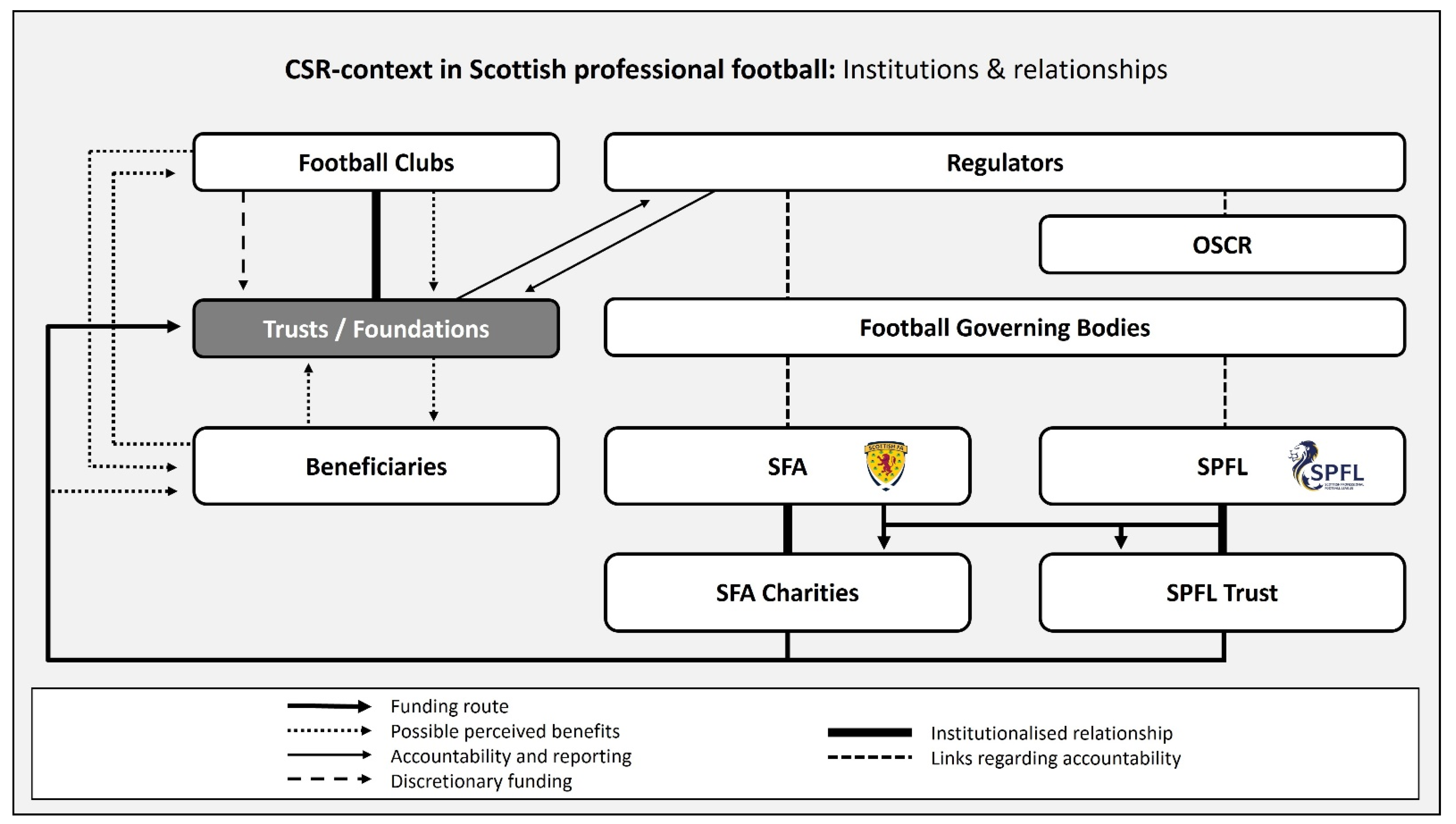

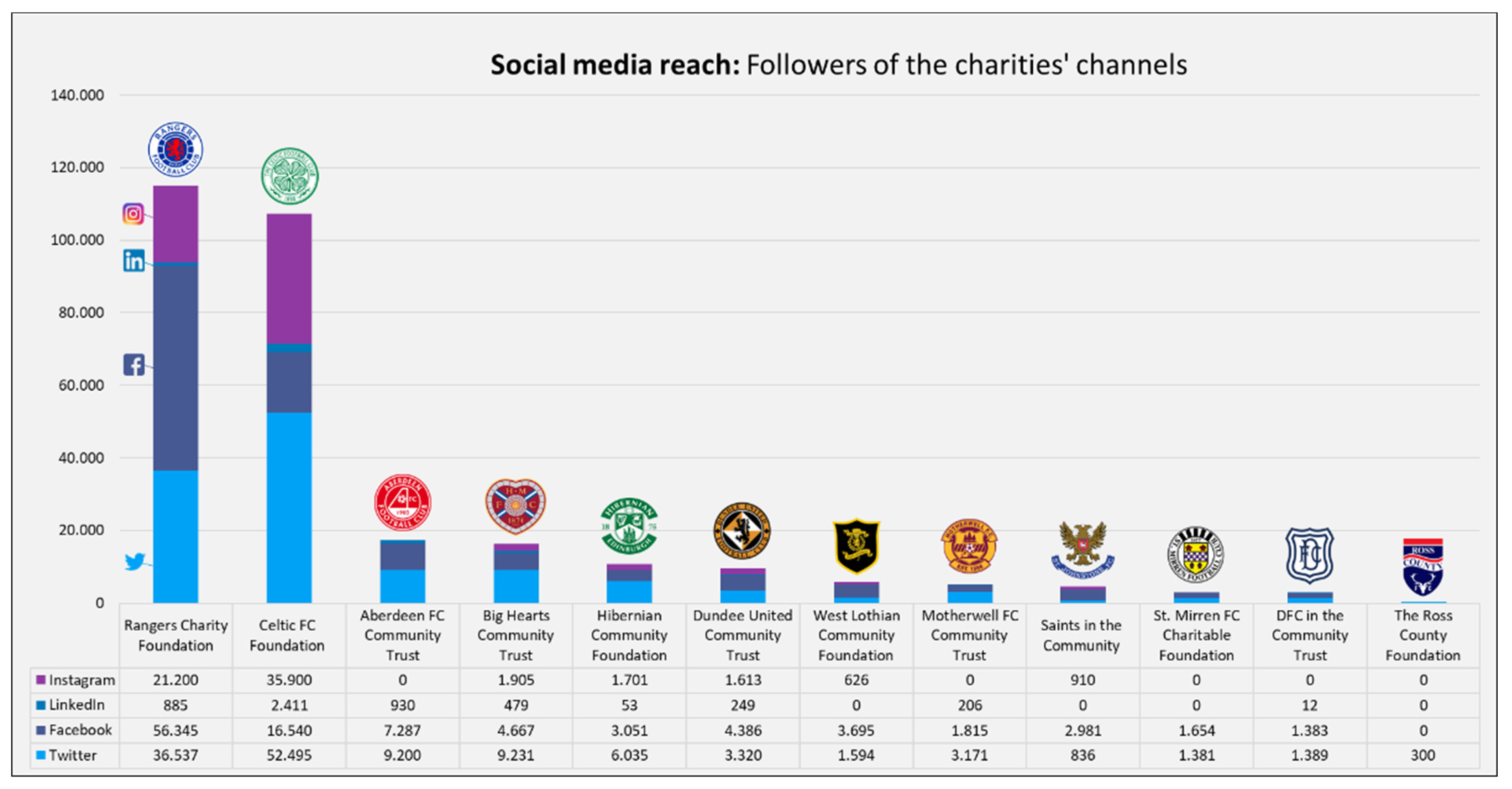

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Methods and Data Collection

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Resource-Based Challenges

4.2. New Priorities and Appoaches

“Previously [we had] a list of programmes that we delivered to different groups of people. What we probably had during COVID was the groups of people and then the ways that we got to those people rather than it necessarily be[ing] about the programme that they were supposed to be part of”.(interview with Heart of Midlothian)

4.3. Same but Different

“We had their [club] staff supporting some of our initiatives and senior people at the club were really interested in what we were doing because […] there wasn’t the normal business model. […] Perhaps the spotlight was a bit more on [us]”.(interview with Heart of Midlothian)

| Club Charity | Types of CSR-Activities during COVID-19 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Resources and Digital Accessibility | Food and Essentials Deliveries | Help for NHS Staff | International Support | Mental Health and Check-Ins | Physical Activity | Virtual Events and Meetings | Dedicated COVID-19 Slogan/Initiative Exemplary Activities | |

| Aberdeen FC Community Trust | ✔5 | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | “Still Standing (Free)”

|

| Big Hearts Community Trust | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | –

|

| Celtic FC Foundation | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | “The Football for Good Fund”

|

| DFC in the Community Trust | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | “Dundee Together”

|

| Dundee United Community Trust | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | “United Against COVID-19”

|

| Hibernian Community Foundation | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | –

|

| Motherwell FC Community Trust | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | –

|

| Rangers Charity Foundation | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | “A Foundation from Home”

|

| St. Mirren FC Charitable Foundation | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | “Buddie-Ing Up”

|

| The Ross County Foundation | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | “For Our People”

|

| The St. Johnstone Community Trust | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | “Give & Go”

|

| West Lothian Community Foundation | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ | –

|

4.4. Decision Making and Strategic Learnings

“You can do a [video call] really quickly instead of driving and meeting and then you have to be polite and have a coffee […] before the actual chat and then you drive back. […] You can […] schedule more into your day”.(interview with Motherwell)

5. Implications and Outlook

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this paper, the terms charity, foundation, trust and charitable organisation are used interchangeably. All entities are arm’s length organisations meaning legally separate units with a clear link to the parent football club. |

| 2 | Total: GBP 2.1 m—all 42 SPFL clubs applied for the respective GBP 50,000 to support club and community (SPFL Trust 2021). |

| 3 | Total: GBP 300,000—all 30 eligible club associated charities applied for the respective GBP 10,000 (SPFL Trust 2021). |

| 4 | e.g., National Lottery, RS MacDonald, Robertson Trust, SPFL Trust. |

| 5 | ✔ = based on accessible communications, the topics were (partially) addressed; ✖ = topics were not addressed. |

References

- Adams, Andrew, Stephen Morrow, and Ian Thomson. 2017. Changing boundaries and evolving organizational forms in football: Novelty and variety among Scottish clubs. The Journal of Sport Management 31: 161–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, George. 1976. The economics of caste and of the rat race and other woeful tales. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 90: 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, Abel Duarte, and Michelle O’Shea. 2012. “You only get back what you put in”: Perceptions of professional sport organizations as community anchors. Community Development 43: 656–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, Christos. 2022. COVID-19 and sport related corporate social responsibility. In Routledge Handbook of Sport and COVID-19. Edited by Stephen Frawley and Nico Schulenkorf. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 283–90. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulos, Christos, and David Shilbury. 2013. Implementing corporate social responsibility in English football: Towards multi-theoretical integration. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 3: 268–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, Christos, Terri Byers, and David Shilbury. 2014. Corporate social responsibility in professional team sport organisations: Towards a theory of decision-making. European Sport Management Quarterly 14: 259–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, Christos, Terri Byers, and Dimitrios Kolyperas. 2017. Understanding strategic decision-making through a multi-paradigm perspective: The case of charitable foundations in English football. Sport, Business and Management 7: 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulou, Pinelopi, John Douvis, and Vaios G. Kyriakis. 2011. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in sports: Antecedents and consequences. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Babiak, Kathy M., and Richard Wolfe. 2006. More than just a game? Corporate social responsibility and Super Bowl XL. Sport Marketing Quarterly 15: 214–24. [Google Scholar]

- Babiak, Kathy M., and Richard Wolfe. 2009. Determinants of corporate social responsibility in professional sport: Internal and external factors. Journal of Sport Management 23: 717–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, Kathy M., and Sylvia Trendafilova. 2011. CSR and environmental responsibility: Motives and pressures to adopt green management practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 18: 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas, Angel, and Plácido Rodríguez. 2010. Spanish football clubs’ finances: Crisis and player salaries. International Journal of Sport Finance 5: 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2012. Rangers Football Club Enters Administration. February 14. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-17026172 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- BBC. 2013. Hearts Placed into Administration. June 19. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/22953448 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- BBC. 2016. Motherwell Become Fan-Owned Club for £1. October 28. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/37804898 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- BBC. 2020. Coronavirus: Premier League Players Should Take a Pay Cut. Matt Hancock. April 2. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/52142267 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Beech, John G., and Simon Chadwick. 2013. The Business of Sport Management, 2nd ed. London: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Beech, John, Simon Horsman, and Jamie Magraw. 2010. Insolvency events among English football clubs. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship 11: 236–49. [Google Scholar]

- Beiderbeck, Daniel, Nicolas Frevel, Heiko A. von der Gracht, Sascha Schmidt, and Vera M. Schweitzer. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on the European football ecosystem—A delphi-based scenario analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 165: 120577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, Maria, and Sören Kock. 2000. “Coopetition” in business networks: To co-operate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management 29: 411–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, Tim, and Geoff Walters. 2012. Financial sustainability within UK charities: Community sport trusts and corporate social responsibility partnerships. International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 24: 606–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumrodt, Jens, Douglas Bryson, and John Flanagan. 2012. European football teams’ CSR engagement impacts on customer-based brand equity. Journal of Consumer Marketing 29: 482–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, Alexander John, David Cockayne, Jan Andre Lee Ludvigsen, Kieran Maguire, Daniel Parnell, Daniel Plumley, Paul Widdop, and Rob Wilson. 2020. COVID-19: The return of football fans. Managing Sport and Leisure 27: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, Howard Rothmann. 1953. Social Responsibility of the Businessman. London: Harper and Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Bradish, Cheri, and J. Joseph Cronin. 2009. Corporate social responsibility in sport. Journal of Sport Management 23: 691–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners, 1st ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Breitbarth, Tim, and Lothar Rieth. 2012. Strategy, stakeholder, structure: Key drivers for successful CSR integration in German professional football. In Contextualising Research in Sport: An International Perspective. Edited by Christos Anagnostopoulos. Athens: ATINER, pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Breitbarth, Tim, and Phil Harris. 2008. The role of corporate social responsibility in the football business: Towards the development of a conceptual model. European Sport Management Quarterly 8: 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbarth, Tim, Gregor Hovemann, and Stefan Walzel. 2011. Scoring strategy goals: Measuring corporate social responsibility in professional European football. Thunderbird International Business Review 53: 721–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Adam, Tim Crabbe, Gavin Mellor, Tony Blackshaw, and Chris Stone. 2006. Football and Its Communities: Final Report. London: Manchester Metropolitan University. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Ross. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on Scottish small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Prognosis and policy prescription. Fraser of Allander Economic Commentary 44: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Byers, Terri, Trevor Slack, and Milena Parent. 2012. Key Concepts in Sport Management. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1979. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. The Academy of Management Review 4: 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1991. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEIS. 2016. Corporate Scotland Is Doing Good—But Still a Long Way to Go! January 19. Available online: https://www.ceis.org.uk/corporate-scotland-is-doing-good-but-still-a-long-way-to-go/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Chadwick, Simon. 2009. From outside lane to inside track: Sport management research in the twenty-first century. Management Decision 47: 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, Michael. 2022. Searching for Brother Walfrid: Faith, Community and Football. Ph.D. thesis, University of Stirling, Stirling, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2014. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Czakon, Wojciech. 2018. Network coopetition. In The Routledge Companion to Coopetition Strategies. Edited by Anne Sofie Fernandez, Paul Chiambaretto, Frédéric Le Roy and Wojciech Czakon. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlsrud, Alexander. 2008. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 15: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. 2016. Annual Review of Football Finance 2016: Reboot. Manchester: Sports Business Group. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. 2017. Annual Review of Football Finance 2017: Ahead of the Curve. Manchester: Sports Business Group. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. 2018. Annual Review of Football Finance 2018: Roar Power. Manchester: Sports Business Group. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. 2019. Annual Review of Football Finance 2019: World in Motion. Manchester: Sports Business Group. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. 2020. Annual Review of Football Finance 2020: Home Truths. Manchester: Sports Business Group. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. 2021. Annual Review of Football Finance 2021: Riding the Challenge. Manchester: Sports Business Group. [Google Scholar]

- Doern, Rachel. 2016. Entrepreneurship and crisis management: The experiences of small businesses during the London 2011 riots. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 34: 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewes, Michael, Frank Daumann, and Florian Follert. 2021. Exploring the sports economic impact of COVID-19 on professional soccer. Soccer & Society 22: 125–37. [Google Scholar]

- ECA. 2016. CSR in European Club Football: Best Practices from ECA Member Clubs. Nyon: European Club Association. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Melissa E. Graebner. 2007. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal 50: 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, John. 1997. Partnerships from Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st-Century Business. Oxford: Capstone Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis, Sean, Michael Marck, Calum Paul, and Anita Radon. 2019. Social sponsorships in sport: Context and potential. Paper presented at ANZMAC 2019: Winds of Change: Conference Proceedings, Wellington, New Zealand, December 2–4; pp. 891–94. [Google Scholar]

- Faranda, Thomas W. 1991. Uncommon Sense Leadership: Principles to Grow Your Business Profitably. Deerfield: Knowledge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feuillet, Antoine, Mickael Terrien, Nicolas Scelles, and Christophe Durand. 2021. Determinants of coopetition and contingency of strategic choices: The case of professional football clubs in France. European Sport Management Quarterly 21: 748–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifka, Matthias, and Johannes Jäger. 2020. CSR in professional European football: An integrative framework. Soccer & Society 21: 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Kai, and Justus Haucap. 2020. Does Crowd Support Drive the Home Advantage in Professional Soccer? Evidence from German Ghost Games during the COVID-19 Pandemic. CESifo Working Paper No. 344. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf Institute for Competition Economics (DICE). [Google Scholar]

- François, Aurélien, Emmanuel Bayle, and Jean-Pascal Gond. 2019. A multilevel analysis of implicit and explicit CSR in French and UK professional sport. European Sport Management Quarterly 19: 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Edward. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman Series in Business and Public Policy; London: Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Milton. 1970. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. Times Magazine, September 13, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichs, Katharina, and Annette Kluge. 2018. Wahrnehmung und Verständnis des Corporate Social Responsibility im Profifußball aus Sicht der Fans. Umweltpsychologie 22: 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-del-Barrio, Pedro, and Stefan Szymanski. 2009. Goal! Profit maximization versus win maximization in soccer. Review of Industrial Organization 34: 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulakis, Chrysostomos, and Joris Drayer. 2009. “Thugs” versus “good guys”: The impact of NBA cares on player image. European Sport Management Quarterly 9: 453–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Todd, and John Peloza. 2011. How does corporate social responsibility create value for consumers? Journal of Consumer Marketing 28: 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, Greg, Arwen Bunce, and Laura Johnson. 2006. How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamil, Sean, and Stephen Morrow. 2011. Corporate social responsibility in the Scottish Premier League: Context and motivation. European Sport Management Quarterly 11: 143–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamil, Sean, Stephen Morrow, Catharine Idle, and Lauren O’Leary. 2009. Corporate social responsibility in the Scottish Premier League (with some reference to English and European football): A critical perspective. In Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Sports. Edited by Plácido Rodríguez, Stefan Késenne and Helmut Dietl. Oviedo: Ediciones de la Universidad de Oviedo, pp. 81–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt, Joan, Fabian Eggers, Sascha Kraus, Paul Jones, and Matthias Filser. 2020. Entrepreneurial orientation in sports entrepreneurship—A mixed methods analysis of professional soccer clubs in the German-speaking countries. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 16: 839–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, Jonas, Sascha Kraus, and Paul Jones. 2022. Sport entrepreneurship: Definition and conceptualization. Journal of Small Business Strategy 32: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, Jonas, Susanne Durst, Sascha Kraus, and Kaisu Puumalainen. 2021. Professional football clubs and empirical evidence from the COVID-19 crisis: Time for sport entrepreneurship? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 165: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Hongwei, and Lloyd Harris. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. Journal of Business Research 116: 176–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heine, Carmen. 2009. Gesellschaftliches Engagement im Fußball: Wirtschaftliche Chancen und Strategien für Vereine. In KulturKommerz. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag, vol. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Horky, Thomas. 2021. No sports, no spectators—No media, no money? The importance of spectators and broadcasting for professional sports during COVID-19. Soccer & Society 22: 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hovemann, Gregor, Tim Breitbarth, and Stefan Walzel. 2011. Beyond sponsorship? Corporate social responsibility in English, German and Swiss top national league football clubs. Journal of Sponsorship 4: 383–52. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, Yuhei, and Aubrey Kent. 2012. Investigating the role of corporate credibility in corporate social marketing: A case study of environmental initiatives by professional sport organizations. Sport Management Review 15: 330–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, Johannes, and Matthias Fifka. 2020. A comparative study of corporate social responsibility in English and German professional football. Soccer & Society 21: 802–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jaidka, Sahil. 2021. Hearts Become Largest Fan-Owned Club in the UK as Ann Budge Transfers Shares to Foundation of Hearts. Sky Sports. August 30. Available online: https://www.skysports.com/football/news/11790/12395375/hearts-become-largest-fan-owned-club-in-the-uk-as-ann-budge-transfers-shares-to-foundation-of-hearts (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- James, Kieran, Mark Murdoch, and Xin Guo. 2018. Corporate social responsibility reporting in Scottish football: A Marxist analysis. Journal of Physical Fitness, Medicine & Treatment in Sports 2: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- JHU. 2022. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. January 4. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Kay, Joyce, and Wray Vamplew. 2010. Beyond altruism: British football and charity, 1877–1914. Soccer & Society 11: 181–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kolyperas, Dimitrios, and Leigh Sparks. 2011. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) communications in the G-25 football clubs. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 10: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyperas, Dimitrios, Christos Anagnostopoulos, Simon Chadwick, and Leigh Sparks. 2016. Applying a communicating vessels framework to CSR value co-creation: Empirical evidence from professional team sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management 30: 702–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyperas, Dimitrios, Stephen Morrow, and Leigh Sparks. 2015. Developing CSR in professional football clubs: Drivers and phases. Corporate Governance 15: 177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, Jörg, April Henning, and Lindsay Parks Pieper. 2021a. Time Out: Global Perspectives on Sport and the COVID-19 Lockdown. Champaign: Common Ground. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, Jörg, April Henning, Lindsay Parks Pieper, and Paul Dimeo. 2021b. Time Out: National Perspectives on Sport and the COVID-19 Lockdown. Champaign: Common Ground. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczycki, Wojciech, and Joerg Koenigstorfer. 2016. Doing good in the right place: City residents’ evaluations of professional football teams’ local (vs. distant) corporate social responsibility activities. European Sport Management Quarterly 16: 502–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Tianyu, Lulu Hao, Jakub Kubiczek, and Adrian Pietrzyk. 2021. Corporate social responsibility of sports club in the era of coronavirus pandemic. Zagłębie Sosnowiec case study. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 35: 2073–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgreen, Adam, and Valérie Swaen. 2010. Corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Management Reviews 12: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobillo Mora, Gema, Xavier Ginesta, and Jordi de San Eugenio Vela. 2021. Corporate Social Responsibility and Football Clubs: The Value of Environmental Sustainability as a Basis for the Rebranding of Real Betis Balompié in Spain. Sustainability 13: 13689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carril, Samuel, and Christos Anagnostopoulos. 2020. COVID-19 and soccer teams on Instagram: The case of corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Sport Communication 13: 447–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, Isabelle, and O. C. Ferrell. 2001. Antecedents and benefits of corporate citizenship: An investigation of French businesses. Journal of Business Research 51: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoli, Argyro Elisavet. 2015. Promoting corporate social responsibility in the football industry. Journal of Promotion Management 21: 335–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, François, Adam Lindgreen, and Valérie Swaen. 2009. Designing and implementing corporate social responsibility: An integrative framework grounded in theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics 87: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Joshua D., and James P. Walsh. 2003. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly 48: 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, Philipp, and Thomas Fenzl. 2019. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung. Edited by Nina Baur and Jörg Blasius. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 633–48. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, Josh, Andrew Adams, and Kate Sang. 2020. Ethical strategists in Scottish football: The role of social capital in stakeholder engagement. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics 14: 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, Josh. 2018. An Investigation into How Social Capital Influences Board Effectiveness within the Context of Scottish Football. Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK. Available online: www.ros.hw.ac.uk (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Miklian, Jason, and Kristian Hoelscher. 2022. SMEs and exogenous shocks: A conceptual literature review and forward research agenda. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 40: 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Ronald K., Bradley R. Agle, and Donna J. Wood. 1997. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review 22: 853–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, Lois A., Deborah J. Webb, and Katherine E. Harris. 2001. Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. The Journal of Consumer Affairs 35: 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Neil, and Roger Levermore. 2012. English professional football clubs. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 2: 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, Stephen. 1999. The New Business of Football. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, Stephen. 2003. The People’s Game? Football, Finance and Society. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, Stephen. 2006. Scottish football: It’s a funny old business. Journal of Sports Economics 7: 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, Stephen. 2012. Corporate social responsibility in sport. In Routledge Handbook of Sport Management. Edited by Leigh Robinson, Packianathan Chelladurai, Guillaume Bodet and Paul Downward. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 101–15. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, Stephen. 2013. Football club financial reporting: Time for a new model? Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 3: 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, Stephen. 2015. Power and logics in Scottish football: The financial collapse of Rangers FC. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 5: 325–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, Stephen. 2017. Football, economics and finance. In Routledge Handbook of Football Studies. Edited by John Hughson, Kevin Moore, Ramón Spaaij and Joseph Maguire. London: Routledge, pp. 163–76. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, Stephen. 2021. For the good of the game? Resolving an existential crisis in Scottish football. In Time Out: National Perspectives on Sport and the COVID-19 Lockdown. Edited by Jörg Krieger, April Henning, Lindsay Parks Pieper and Paul Dimeo. Champaign: Common Ground, pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Janice M., Michael Barret, Maria Mayan, Karin Olson, and Jude Spiers. 2002. Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. The International Journal of Qualitative Methods 1: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalebuff, Barry, and Adam Brandenburger. 2007. Coopetition—Kooperativ konkurrieren. Mit der Spieltheorie zum Unternehmenserfolg. In Das Summa Summarum des Management: Die 25 wichtigsten Werke für Strategie, Führung und Veränderung. Edited by Cornelius Boersch and Rainer Elschen. Wiesbaden: Gabler, pp. 217–30. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, Walter C. 1964. The peculiar economics of professional sports: A contribution to the theory of the firm in sporting competition and in market competition. Quarterly Journal of Economics 93: 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, Daniel, Alexander John Bond, Paul Widdop, and David Cockayne. 2021. Football worlds: Business and networks during COVID-19. Soccer & Society 22: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, Daniel, Paul Widdop, Alexander John Bond, and Rob Wilson. 2022. COVID-19, networks and sport. Managing Sport and Leisure 27: 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, Lindsay. 2002. Scottish social democracy and Blairism: Difference, diversity and community. In Tomorrow’s Scotland. Edited by Gerry Hassan and Chris Warhurst. London: Lawrence and Wishart, pp. 116–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey, and Gerald R. Salancik. 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Plumley, Daniel, Robbie Millar, Adam Davis, Richard Coleman, and Rob Wilson. 2022. Counting the Cost of COVID-19 on Professional Football Clubs and Their Communities. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2002. The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harvard Business Review 80: 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2006. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review 84: 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ratten, Vanessa, and João J. Ferreira. 2016. Sport entrepreneurship: Concepts and theory. In Sport Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Edited by Vanessa Ratten and João Ferriera. London: Taylor & Francis, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Reade, James, Dominik Schreyer, and Carl Singleton. 2020. Echoes: What Happens When Football Is Played behind Closed Doors? Economics Discussion Papers. Reading: Department of Economics, University of Reading. [Google Scholar]

- Reiche, Danyel. 2014. Drivers behind corporate social responsibility in the professional football sector: A case study of the German Bundesliga. Soccer & Society 15: 472–502. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, João, Manuel Castelo Branco, and João Alves Ribeiro. 2019. The corporatisation of football and CSR reporting by professional football clubs in Europe. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 20: 242–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, Hugo A. P., Otávio Baggiotto Bettega, and Rodolfo A. Dellagrana. 2021. An analysis of Bundesliga matches before and after social distancing by COVID-19. Science and Medicine in Football 5: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Scelles, Nicolas, Stefan Szymanski, and Nadine Dermit-Richard. 2018. Insolvency in French Soccer: The case of payment failure. Journal of Sport Economics 19: 603–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. 2021. COVID Impacts Scotland’s Finances: Pandemic has “Shifted the Fiscal Landscape”. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/news/COVID-impacts-scotlands-finances/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Senaux, Benoit. 2008. A stakeholder approach to football club governance. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 4: 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Silberhorn, Daniel, and Richard C. Warren. 2007. Defining corporate social responsibility. European Business Review 19: 352–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane, Peter. 2014. Club objectives. In Handbook on the Economics of Professional Football. Edited by J. Goddard and P. Sloane. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Aaron C. T., and Hans M. Westerbeek. 2007. Sport as a vehicle for deploying corporate social responsibility. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 25: 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Danielle K., and Jonathan Casper. 2020. Making an impact: An initial review of U.S. sport league corporate social responsibility responses during COVID-19. International Journal of Sport Communication 13: 335–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPFL Trust. 2021. COVID-19 Impact Report. Glasgow. Available online: https://spfltrust.org.uk/COVID-19-impact-report/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- SPICe. 2021. Timeline of Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Scotland. Edinburgh: The Scottish Parliament. Available online: https://spice-spotlight.scot/2021/12/10/timeline-of-coronavirus-COVID-19-in-scotland/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Statista Research Department. 2021. Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on the Global Economy. Statista. March 23. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/6139/COVID-19-impact-on-the-global-economy/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Szymanski, Stefan, and Daniel Weimar. 2019. Insolvencies in professional football: A German Sonderweg? International Journal of Sport Finance 14: 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Herald. 2021. ‘Historic Day’: St Mirren’s ‘Future Safeguarded’ as It Becomes Fan-Owned. July 27. Available online: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/homenews/19471705.st-mirren-fc-taken-unique-fan-ownership-structure-charity/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Thormann, Tim F., and Pamela Wicker. 2021. The perceived corporate social responsibility of major sport organizations by the German public: An empirical analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 3: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovar, Jorge. 2021. Soccer, World War II and coronavirus: A comparative analysis of how the sport shut down. Soccer & Society 22: 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Transfermarkt. 2021. Scottish Premiership—Attendance Figures. Available online: https://www.transfermarkt.com/scottish-premiership/besucherzahlen/wettbewerb/SC1/plus/?saison_id=2020 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Trendafilova, Sylvia, Vassilios Ziakas, and Emily S. Sparvero. 2017. Linking corporate social responsibility in sport with community development: An added source of community value. Sport in Society 20: 938–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamplew, Wray. 1982. The economics of a sports industry: Scottish gate-money football, 1890–1914. The Economic History Review 35: 540–67. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Matthew, and Aubrey Kent. 2009. Do fans care? Assessing the influence of corporate social responsibility on consumer attitudes in the sport industry. Journal of Sport Management 23: 743–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Matthew, Bob Heere, Milena M. Parent, and Dan Drane. 2010. Social responsibility and the Olympic Games: The mediating role of consumer attributions. Journal of Business Ethics 95: 659–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, Geoff, and Christos Anagnostopoulos. 2012. Implementing corporate social responsibility through social partnerships. Business Ethics: A European Review 21: 417–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, Geoff, and Mark Panton. 2014. Corporate social responsibility and social partnerships in professional football. Soccer & Society 15: 828–46. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Geoff, and Richard Tacon. 2011. Corporate Social Responsibility in European Football: A Report Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294583017_Corporate_social_responsibility_in_European_football (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Walters, Geoff, and Richard Tacon. 2013. Stakeholder engagement in European football. In Routledge Handbook of Sport and Corporate Social Responsibility. Edited by Juan Luis Paramio Salcines, Kathy M. Babiak and Geoff Walters. London: Routledge, pp. 260–72. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Geoff, and Simon Chadwick. 2009. Corporate citizenship in football: Delivering strategic benefits through stakeholder engagement. Management Decision 47: 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, Geoff. 2009. Corporate social responsibility through sport: The community sports trust model as a CSR delivery agency. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 35: 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzel, Stefan, Jonathan Robertson, and Christos Anagnostopoulos. 2018. Corporate social responsibility in professional team sports organizations: An integrative review. Journal of Sport Management 32: 511–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzel, Stefan. 2019. Corporate Social Responsibility und Fußball—Ein Rückblick auf zehn Jahre internationale Forschung. In Management-Reihe Corporate Social Responsibility. CSR und Fußball. Edited by Marc Werheid. New York: Springer, pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Westmattelmann, Daniel, Jan-Gerrit Grotenhermen, Marius Sprenger, and Gerhard Schewe. 2020. The show must go on—Virtualisation of sport events during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Information Systems 29: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WGSIFC. 2015. Supporter Involvement in Football Clubs; Report of the Working Group on Supporter Involvement in Football Clubs to the Minister for Sport, Health Improvement and Mental Health. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Woratschek, Herbert, Chris Horbel, and Bastian Popp. 2014. Value co-creation in sport management. European Sport Management Quarterly 14: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyper, Grant M. A., Eilidh Fletcher, Ian Grant, Oliver Harding, Maria Teresa de Haro Moro, Diane L. Stockton, and Gerry McCartney. 2021. Inequalities in population health loss by multiple deprivation: COVID-19 and pre-pandemic all-cause disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in Scotland. International Journal for Equity in Health 20: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Eun-Surk Yi, Young-Jae Jeong, II-Gwang Kim, Joo-Young Kim, and Ji-Hyun Lee. 2017. A study on the analysis of club official’s intention of continuous implementation according to the CSR (levels and types) of professional sport team. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 12: 3565–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zeimers, Géraldine, Christos Anagnostopoulos, Thierry Zintz, and Annick Willem. 2018. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in football: Exploring modes of CSR implementation. In Routledge Handbook of Football Business and Management. Edited by Simon Chadwick, Daniel Parnell, Paul Widdop and Christos Anagnostopoulos. London: Routledge, pp. 114–30. [Google Scholar]

| Turnover Metric | Attendance Metric (Average Home Attendance 2019/2020) | Clubs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large clubs | >GBP 30 m p.a. | >20,000 | Celtic, Rangers |

| Medium-sized clubs | GBP 5 m–30 m p.a. | 10,000–20,000 | Aberdeen, Hearts, Hibernian |

| Smaller clubs | <GBP 5 m p.a. | <10,000 | Dundee FC, Dundee United, Kilmarnock, Motherwell, Ross County, St. Johnstone, St. Mirren |

| Club Charity | Job Description | Date | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Celtic FC Foundation | Chief Executive | 10 November 2021 | 36 min |

| Big Hearts Community Trust | General Manager | 16 November 2021 | 43 min |

| Motherwell FC Community Trust | Community Partnership Officer | 17 November 2021 | 49 min |

| The St. Johnstone Community Trust | Chief Executive | 30 November 2021 | 56 min |

| Club | Aberdeen | Celtic | Dundee FC | Dundee United | Heart of Midlothian | Hibernian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formed | 1903 | 1887 | 1893 | 1909 | 1874 | 1875 |

| Average home attendance (2019/2020) | 13,836 | 57,944 | 5277 | 8496 | 16,751 | 16,729 |

| Final league rank (2020/2021) | 4 | 2 | promoted | 10 | promoted | 3 |

| Scottish championships won | 4 | 51 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Revenue (in GBP million) | 11.1 (2020/2021) | 60.8 (2020/2021) | abbreviated annual account without revenue details | 3.9 (2019/2020) | 7.7 (2020/2021) | 8.9 (2019/2020) |

| CSR disclosure (in latest annual report) | Environment, Charity | Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Social Responsibility | – | – | Corporate Social Responsibility | – |

| CSR structure | ||||||

| Type | Trust | Foundation | Trust | Trust | Trust | Foundation |

| Name | Aberdeen FC Community Trust | Celtic FC Foundation | DFC in the Community Trust | Dundee United Community Trust | Big Hearts Community Trust | Hibernian Community Foundation |

| Established | 2014 | 1996 (Celtic Charity Fund till 2013) | 2017 | 2008 | 2006 (rebranding 2015) | 2008 |

| Constitutional form | SCIO | SCIO | SCIO | registered with company | registered with company | registered with company |

| Mission statement | To provide support and opportunity to change lives for the better. | To create opportunities for society’s most vulnerable and marginalised groups—principally, we address root causes of poverty by equipping individuals with the tools and means to reverse inequality. | To use the passion for the club and its ethos of self-belief, belonging and youth development, to engage those who need our help. | To use the brand of Dundee United Football Club to improve the lives of people in Dundee and the surrounding area. | To bring community resources together to offer adults and children free opportunities to help them live a safe and fulfilling life. | To use the power of sport, and in particular football, to motivate, inspire and educate people in our communities to profoundly change their live for the better. |

| Pillars |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Club | Livingston | Motherwell | Rangers | Ross County | St. Johnstone | St. Mirren |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formed | 1943 | 1886 | 1872 | 1929 | 1884 | 1877 |

| Average home attendance (2019/2020) | 3184 | 5575 | 49,238 | 4665 | 4091 | 5376 |

| Final league rank (2020/2021) | 6 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 7 |

| Scottish championships won | 0 | 1 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Revenue (in GBP million) | abbreviated annual account without revenue details | 4.9 (2019/2020) | 47.7 (2020/2021) | abbreviated annual account without revenue details | abbreviated annual account without revenue details | 4.1 (2019/2020) |

| CSR disclosure (in latest annual report) | – | – | Community and Charity, Energy and Carbon | – | – | – |

| CSR structure | ||||||

| Type | Foundation | Trust | Foundation | Foundation | Trust | Foundation |

| Name | West Lothian Community Foundation | Motherwell FC Community Trust | Rangers Charity Foundation | The Ross County Foundation | The St. Johnstone Community Trust | St Mirren FC Charitable Foundation |

| Established | 2011 (initially Youth Foundation) | 2011 | 2002 (relaunch 2017) | 2015 | 2016 | 2013 (relaunch 2018) |

| Constitutional form | registered with company | registered with company | SCIO | SCIO | SCIO | SCIO |

| Mission statement | To use football to promote the educational and health development with particular emphasis on targeting those who are typically less engaged with these activities and may be failing to achieve their full potential. | Delivering a wide range of activities across Lanarkshire using the power of football to change lives every day. | To bring the club, supporters, staff and players together in a unique way to help make a world of difference to thousands of lives through charitable and community work. | To provide opportunity, encouragement and change for the better. | A thriving, sustainable, community focused organisation, providing positive life enhancing experiences using sport and football in particular to help people throughout Perth and Kinross achieve their goals. | To create strong community links through our diverse programmes, offering an opportunity for all to engage in activity. |

| Pillars |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oeckl, S.J.S.; Morrow, S. CSR in Professional Football in Times of Crisis: New Ways in a Challenging New Normal. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2022, 10, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs10040086

Oeckl SJS, Morrow S. CSR in Professional Football in Times of Crisis: New Ways in a Challenging New Normal. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2022; 10(4):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs10040086

Chicago/Turabian StyleOeckl, Severin J. S., and Stephen Morrow. 2022. "CSR in Professional Football in Times of Crisis: New Ways in a Challenging New Normal" International Journal of Financial Studies 10, no. 4: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs10040086

APA StyleOeckl, S. J. S., & Morrow, S. (2022). CSR in Professional Football in Times of Crisis: New Ways in a Challenging New Normal. International Journal of Financial Studies, 10(4), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs10040086