Introducing the PrimeD Framework: Teacher Practice and Professional Development through Shulman’s View of Professionalism

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How does the application of PrimeD to secondary mathematics teacher preparation serve as an action framework to guide program transformation?

- How does the application of PrimeD to secondary mathematics teacher preparation improve PST outcomes? What are the challenges? How can those challenges be addressed?

2. Background Rationale for Connecting PD to Professionalism

“The fundamental difference between an amateur and a professional in any field is not one of intelligence or willingness to work hard. Rather, it is that professionals are trained at accessing their own research field, and therefore are much less likely to spend time repeating the others’ prior mistakes. Educational reforms seem to have a less-than-glorious tradition of replicating major aspects of previous failed efforts.”([12], p. 197)

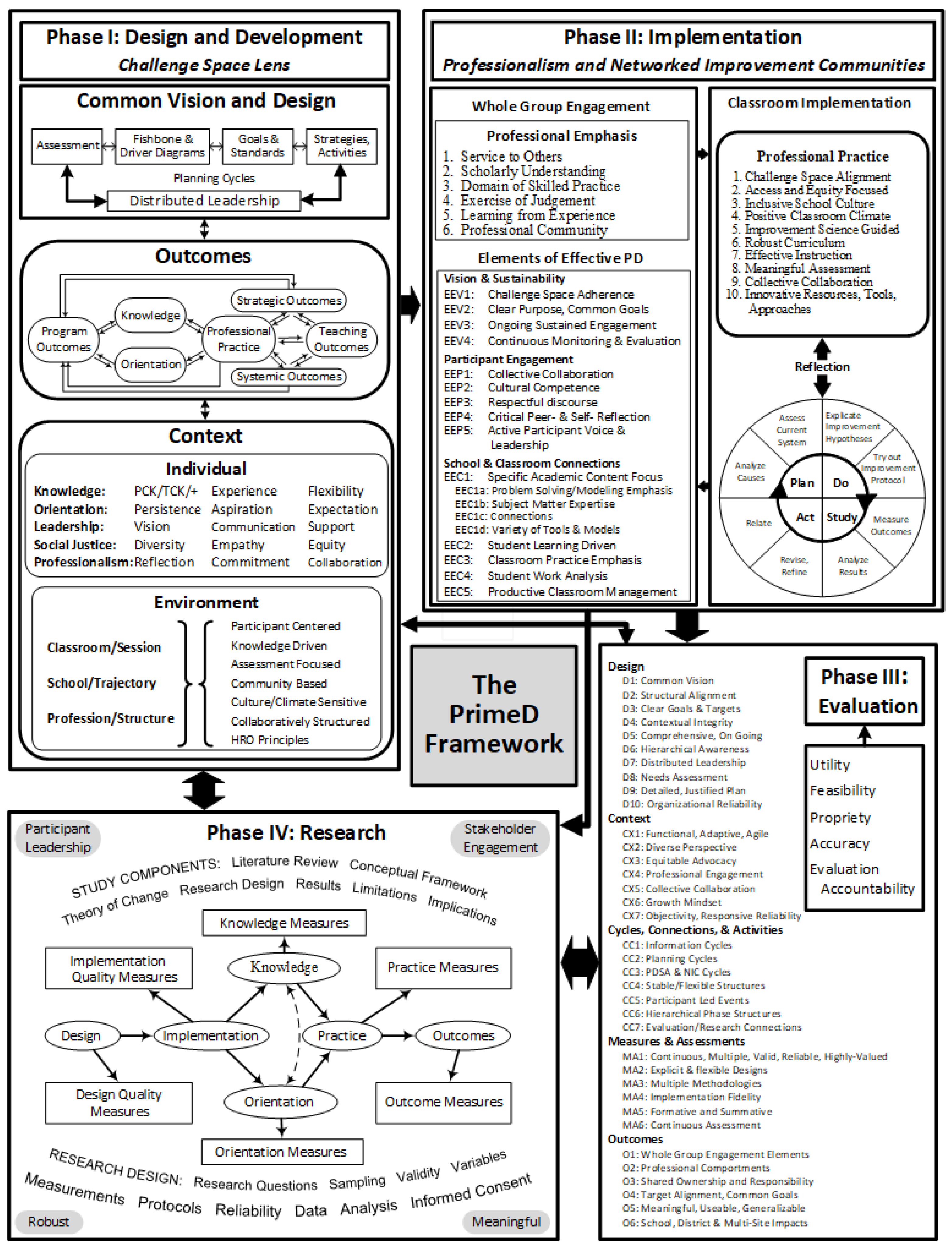

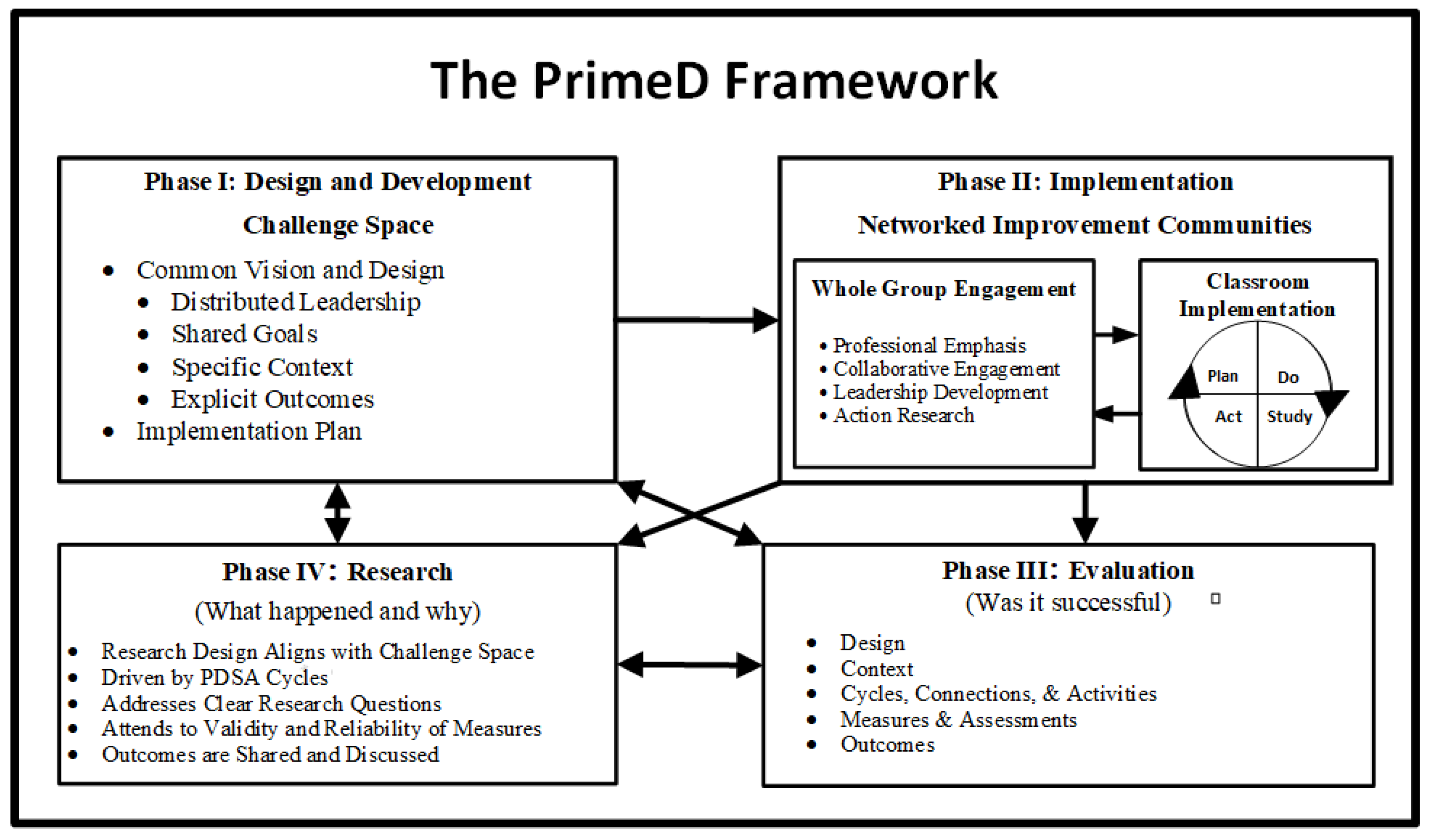

2.1. A Framework Grounded in Professionalism

2.1.1. Phase I Design and Development: Getting Everybody on the Same Page

2.1.2. Phase II Implementation: Connecting Classroom Practice to Whole-Group Activities

2.1.3. Phase III Evaluation: Members of a Profession Establish What Is Best Practice

2.1.4. Phase IV Research: Members of a Profession Generate Knowledge Associated with Practice

3. NICs as a Research and Evaluation Driver

3.1. Research AS PD

3.2. Research ON PD

3.3. [Research ON PD] AS PD

4. Illustrations of Professionalism Supported by PrimeD

4.1. Theme 1: Connecting NICs to Coursework

4.2. Theme 2: Building Effective PDSA Cycles

4.3. Theme 3: Collaborative Discussions in Professional Communities

4.4. Theme 4: PDSA Cycle Challenges

4.5. Theme 5: Time Constraints

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Shulman, L.S. Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S.; Keislar, E.R.; Stanford, U.; Stanford University, Social Science Research Council. Committee on Learning and the Educational Process. Learning by Discovery: A Critical Appraisal; Rand McNally: Skokie, IL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L.S.; Wilson, S.M. The Wisdom of Practice: Essays on Teaching, Learning, and Learning to Teach; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L.S. Theory, Practice, and the Education of Professionals. Elem. Sch. J. 1998, 98, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saderholm, J.; Ronau, R.; Rakes, C.; Bush, S.; Mohr-Schroeder, M. The critical role of a well-articulated, coherent design in professional development: An evaluation of a state-wide two-week program for mathematics and science teachers. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2016, 43, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakes, C.R.; Bush, S.B.; Mohr-Schroeder, M.J.; Ronau, R.N.; Saderholm, J. Making teacher PD effective using the PrimeD framework. N. Engl. Math. J. 2017, 50, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Principles to Actions: Ensuring Mathematical Success for All; National Council of Teachers of Mathematics: Reston, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rakes, C.R.; Saderholm, J.; Bush, S.B.; Mohr-Schroeder, M.J.; Ronau, R.N.; Stites, M.L. Structuring secondary mathematics teacher preparation through a professional development framework. Int. J. Res. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 194–208. Available online: https://ijres.org/papers/Volume-10/Issue-12/1012194208.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Bryk, A.S.; Gomez, L.M.; Grunow, A.; LeMahieu, P.G. Learning to Improve: How America’s Schools can Get Better at Getting Better; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stringfield, S. Attempting to Enhance Students’ Learning through Innovative Programs: The Case for Schools Evolving into High Reliability Organizations 1. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 1995, 6, 67–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringfield, S.; Reynolds, D.; Schaffer, E. Improving secondary students’ academic achievement through a focus on reform reliability: 4- and 9-year findings from the High Reliability Schools project. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2008, 19, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datnow, A.; Stringfield, S. Working Together for Reliable School Reform. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk (JESPAR) 2000, 5, 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, L. Teacher Leadership: The Missing Factor in America’s Classrooms. Clear. House A J. Educ. Strateg. Issues Ideas 2020, 93, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, A.; Claxton, H.; Wilson, A. Key characteristics of Teacher leaders in schools. Adm. Issues J. Educ. Pract. Res. 2014, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks-Horsley, S.; Stiles, K.E.; Mundry, S.; Love, N.; Hewson, P.W. Designing Professional Development for Teachers of Science and Mathematics, 3rd ed.; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Driskell, S.O.; Bush, S.B.; Ronau, R.N.; Niess, M.L.; Rakes, C.R.; Pugalee, D. Mathematics education technology professional development: Changes over several decades. In Handbook of Research on Transforming Mathematics Teacher Education in the Digital Age; Niess, M.L., Driskell, S.O., Hollebrands, K.F., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.; Rowe, A.K. Developing class-consciousness leadership education in graduate and professional schools. New Dir. Stud. Leadersh. 2021, 2021, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupšienė, L.; Bredelyte, A. The characteristics of teacher leadership. Tiltai 2010, 53, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Pearson: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, P. Week 19: Ways of Framing the Difference between Research and Evaluation. Better Evaluation Newsletter. 2014. Available online: https://www.betterevaluation.org/blog/week-19-ways-framing-difference-between-research-evaluation (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Schaffer, E.; Reynolds, D.; Stringfield, S.C. Sustaining Turnaround at the School and District Levels: The High Reliability Schools Project at Sandfields Secondary School. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk (JESPAR) 2012, 17, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.T.; Borko, H. What Do New Views of Knowledge and Thinking Have to Say about Research on Teacher Learning? Educ. Res. 2000, 29, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garet, M.S.; Porter, A.C.; Desimone, L.; Birman, B.F.; Yoon, K.S. What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2001, 38, 915–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, I.R.; Gellatly, G.B.; Montgomery, D.L.; Ridgway, C.J.; Templeton, C.D.; Whittington, D. Executive Summary of the Local Systemic Change through Teacher Enhancement Year Four Cross-Site Report; Horizon Research: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. Change Theory: A Force for School Improvement; Seminar Series Paper No. 157; Centre for Strategic Education: East Melbourne, Australia, 2006; Available online: https://michaelfullan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/13396072630.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2017).

- Guskey, T. Does It Make a Difference? Evaluating Professional Development. Educ. Leadersh. 2002, 59, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, S.B.; Cook, K.L.; Ronau, R.N.; Rakes, C.R.; Mohr-Schroeder, M.J.; Saderholm, J. A highly structured collaborative STEAM program: Enacting a professional development framework. J. Res. STEM Educ. 2018, 2, 106–125. Available online: https://j-stem.net/index.php/jstem/article/view/25/23 (accessed on 1 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- Timperley, H.S. Realizing the Power of Professional Learning; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough, D.; Shulha, L.; Hopson, R.; Carrunthers, F. The Program Evaluation Standards, 3rd ed.; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010.

- Anderson, T.; Shattuck, J. Design-Based Research. Educ. Res. 2012, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.L.; Knowles, J.G. Teacher Development Partnership Research: A Focus on Methods and Issues. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1993, 30, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Hohesee, C.; Hwang, S. A Future Vision of Mathematics Education Research: Blurring the Boundaries of Research and Practice to Address Teachers’ Problems. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2017, 48, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Morris, A.; Hohesee, C.; Hwang, S.; Robbins, S.; Hiebert, J. Clarifying the Impact of Educational Research on Students’ Learning. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2017, 48, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Baker, R. Developing New Knowledge and Practice through Teacher-Researcher Partnerships; International Congress for School Effectiveness and Improvement (ICSEI): Auckland, New Zeland, 2008; Available online: http://tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/pages/developing-new-knowledge.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Drill, K.; Miller, S. Teachers’ Perspectives on Educational Research. Brock Educ. A J. Educ. Res. Pract. 2013, 23, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagemann, E. An Elusive Science: The Troubling History of Education Research; Bibliovault OAI Repository, University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001; p. 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.; Collins, A.; Duguid, P. Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning. Educ. Res. 1989, 18, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Lytle, S.L. Research on Teaching and Teacher Research: The issues that divide. Educ. Res. 1990, 19, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.M.; Berne, J. Chapter 6: Teacher Learning and the Acquisition of Professional Knowledge: An Examination of Research on Contemporary Professional Development. Rev. Res. Educ. 1999, 24, 173–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, C.E.; Penuel, W.R. Research–practice partnerships in education: Outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educ. Res. 2016, 45, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Hohesee, C.; Hwang, S. Making classroom implementation an integral part of research. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2017, 48, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.L.; Cohen, D.K. Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education. In Teaching as the Learning Profession: Handbook of Policy and Practice; Sykes, G., Darling-Hammond, L., Eds.; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, C.E.; Bae, S.; Turner, E.O. Authority, Status, and the Dynamics of Insider-Outsider Partnerships at the District Level. Peabody J. Educ. 2008, 83, 364–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, M.; Christie, D. The role of teacher research in continuing professional development. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2006, 54, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J. Teachers as researchers: Implications for supervision and for teacher education (ED293831). Teach. Teach. Educ. 1990, 6, 1–26. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED293831.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Chow KC, K.; Chu SK, W.; Tavares, N.; Lee CW, Y. Teachers as Researchers: A discovery of Their Emerging Role and Impact Through a School-University Collaborative Research. Brock Educ. J. 2015, 24, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, D. Teacher research for professional development. ELT J. 2007, 62, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Moss, P.A.; Goering, S.; Herter, R.J.; Lamar, B.; Leonard, D.; Robbins, S.; Russell, M.; Templin, M.; Wascha, K. Collaboration as Dialogue: Teachers and Researchers Engaged in Conversation and Professional Development. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1996, 33, 193–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, K. Teacher research as professional development for P–12 educators in the USA. Educ. Action Res. 2003, 11, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenhouse, L. An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development; Heinemann Educational Books Ltd.: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J. Action Research for Educational Change; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- LeMahieu, P.; Nordstrum, L.; Potvin, A. Design-based implementation research. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2017, 25, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamont, S. Fieldwork in Educational Settings. Methods, Pitfalls and Perspectives; Routledge Falmer: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Grbich, C. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saderholm, J.; Ronau, R.N.; Rakes, C.R.; Bush, S.B.; Mohr-Schroeder, M.J. Introducing the PrimeD Framework: Teacher Practice and Professional Development through Shulman’s View of Professionalism. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14091032

Saderholm J, Ronau RN, Rakes CR, Bush SB, Mohr-Schroeder MJ. Introducing the PrimeD Framework: Teacher Practice and Professional Development through Shulman’s View of Professionalism. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(9):1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14091032

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaderholm, Jon, Robert N. Ronau, Christopher R. Rakes, Sarah B. Bush, and Margaret J. Mohr-Schroeder. 2024. "Introducing the PrimeD Framework: Teacher Practice and Professional Development through Shulman’s View of Professionalism" Education Sciences 14, no. 9: 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14091032

APA StyleSaderholm, J., Ronau, R. N., Rakes, C. R., Bush, S. B., & Mohr-Schroeder, M. J. (2024). Introducing the PrimeD Framework: Teacher Practice and Professional Development through Shulman’s View of Professionalism. Education Sciences, 14(9), 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14091032