Disruption Management Interacts with Positive and Negative Emotions in the Classroom: Results from a Simulation-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

Michelle Obama writes in her biography entitled Becoming: “My second-grade classroom turned out to be a mayhem of unruly kids and flying erasers, which had not been the norm in either my experience or Craig’s [her brother]. All this seemed due to a teacher who couldn’t figure out how to assert control—who didn’t seem to like children, even. I sat miserably at my desk, […]—learning nothing and waiting for the midday lunch break, when I could go home and have a sandwich and complain to my mom”. [1]Michelle Obama, Becoming, 2021, p. 32ff.

1.1. Student Emotions

1.2. Teachers’ Disruptions Management

1.3. Previous Research on Disruption Management

1.4. The Current Study

1.5. Research Question and Hypotheses

2. Methods

2.1. Abc Training

- (a)

- Revengeful and punitive behaviour: This uncooperative approach involves immediately following disruptive behaviour with (unreasonably severe) punishment. The interaction is usually aimed at achieving a victory or defeat of the opponent.

- (b)

- Avoiding and evasive behaviour: This approach is characterised by the teacher’s withdrawal, ignoring major disruptions, attempting to evade disruptive students, and avoiding taking a position.

- (c)

- Problem-solving-supportive behaviour: This approach involves calling out the violation of the rule as unacceptable while simultaneously making an effort to support a behaviour change.

2.2. Procedure and Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

4.2. Practical Implications of the Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- The teacher’s intervention was successful.

- The teacher resolved the problem promptly.

- The teacher was able to put an end to the disruptive behaviour.

- The teacher has minimised the disruptive behaviour.

- In some cases, the teacher succeeded in minimising the disruption.

- The teacher’s intervention was only partially successful. (excluded from the analysis due to a negative average covariance)

- The disruptive students did not react to the teacher.

- The teacher did not influence the disruptive behaviour.

- The teacher was unable to stop the disruptive behaviour.

- After the teacher’s reaction, the students were even more disruptive.

- The teacher has reinforced the disruptive behaviour.

- The disruptive students reacted to the teacher’s interventions with reactance.

References

- Obama, M. Becoming; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T. Perceived Learning Environment and Students’ Emotional Experiences: A Multilevel Analysis of Mathematics Classrooms. Learn. Instr. 2007, 17, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, J.R.; Kitsantas, A. Influences of Disciplinary Classroom Climate on High School Student Self-Efficacy and Mathematics Achievement: A Look at Gender and Racial-Ethnic Differences. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2014, 12, 1261–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounin, J.S.; Gump, P.V. The Ripple Effect in Discipline. Elem. Sch. J. 1958, 59, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Muis, K.R.; Frenzel, A.C.; Götz, T. Emotions at School; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, T.; Keller, M.M.; Lüdtke, O.; Nett, U.E.; Lipnevich, A.A. The Dynamics of Real-Time Classroom Emotions: Appraisals Mediate the Relation between Students’ Perceptions of Teaching and Their Emotions. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, R.J.; Marzano, J.S.; Pickering, D.J. Classroom Management That Works: Research-Based Strategies for Every Teacher; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R. The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions: Assumptions, Corollaries, and Implications for Educational Research and Practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. International Handbook of Emotions in Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C.; Pianta, R.C. The Importance of Teacher-Student Relationships for Adolescents with High Incidence Disabilities. Theory Pract. 2007, 46, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenauer, G.; Hascher, T.; Volet, S.E. Teacher Emotions in the Classroom: Associations with Students’ Engagement, Classroom Discipline and the Interpersonal Teacher-Student Relationship. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2015, 30, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Elliot, A.J.; Maier, M.A. Achievement Goals and Discrete Achievement Emotions: A Theoretical Model and Prospective Test. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, U.E.; Bieg, M.; Keller, M.M. How Much Trait Variance is Captured by Measures of Academic State Emotions?: A Latent State-Trait Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2017, 33, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Stephens, E.J. 1.1. Students in Focus. In Emotion, Motivation, and Self-Regulation: A Handbook for Teachers, 1st ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, K.R. Appraisal Theory. In Handbook of Cognition and Emotion; Dalgleish, T., Power, M.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. An Attributional Theory of Achievement Motivation and Emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1985, 92, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being; University of Illinois: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Goetz, T.; Lüdtke, O.; Pekrun, R.; Sutton, R.E. Emotional Transmission in the Classroom: Exploring the Relationship between Teacher and Student Enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläser-Zikuda, M.; Fuß, S. Wohlbefinden von Schülerinnen Und Schülern Im Unterricht [Well-being of Students in the Classroom]. In Schule positiv erleben. Ergebnisse und Erkenntnisse zum Wohlbefinden von Schülerinnen und Schülern [Results and Insights]; Haupt: Bern, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, V. How Do Teachers Learn to Be Effective Classroom Managers? In Handbook of Classroom Management; Everton, C.M., Weinstein, C.S., Eds.; Routledge/Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 897–918. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Grift, W.; Van der Wal, M.; Torenbeek, M. Ontwikkeling in de Pedagogische Didactische Vaardigheid van Leraren in Het Basisonderwijs [Development of Pedagogical and Didactic Skills of Teachers in Primary Education]. Pedagog. Stud. 2011, 88, 416–432. [Google Scholar]

- Kunter, M.; Kleickmann, T.; Klusmann, U.; Richter, D. The Development of Teachers’ Professional Competence. In Cognitive Activation in the Mathematics Classroom and Professional Competence of Teachers; Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Neubrand, M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, B.S.; Hirn, R.G.; Lewis, T.J. Enhancing Effective Classroom Management in Schools: Structures for Changing Teacher Behavior. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. J. Teach. Educ. Div. Counc. Except. Child. 2017, 40, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläser-Zikuda, M. Lehrerexpertise-Analyse Und Bedeutung Unterrichtlichen Handelns [Teacher Expertise: Analysis and Importance of Instructional Actions]; Waxmann Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Lu, L. How Classroom Management and Instructional Clarity Relate to Students’ Academic Emotions in Hong Kong and England: A Multi-Group Analysis Based on the Control-Value Theory. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2022, 98, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, W. Ecological Approaches to Classroom Management. In Handbook of Classroom Management; Evertson, C.M., Weinstein, C.S., Eds.; Routledge/Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, K.S.; Lewis-Palmer, T.; Stichter, J.; Morgan, P.L. Examining the Influence of Teacher Behavior and Classroom Context on the Behavioral and Academic Outcomes for Students with Emotional or Behavioral Disorders. J. Spec. Educ. 2008, 41, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.; Shavit, Y. The Association between Student Reports of Classmates’ Disruptive Behavior and Student Achievement. AERA Open 2016, 2, 2332858416653921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T.; Parker, P.D.; Marsh, H.W.; Kunter, M.; Schmeck, A.; Leutner, D. Self-Efficacy in Classroom Management, Classroom Disturbances, and Emotional Exhaustion: A Moderated Mediation Analysis of Teacher Candidates. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, T.; Kunter, M.; Seiz, J.; Hoehne, V.; Baumert, J. Die Bedeutung des Pädagogisch-Psychologischen Wissens von angehenden Lehrkräften für die Unterrichtsqualität [The Importance of Pedagogical and Psychological Knowledge of Pre-Service Teachers for Teaching Quality]. Z. Pädagog. 2014, 60, 184–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ophardt, D.; Thiel, F. Klassenmanagement: Ein Handbuch Für Studium Und Praxis [Classroom Management: A Handbook for Study and Practice]; Kohlhammer Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Praetorius, A.-K.; Klieme, E.; Herbert, B.; Pinger, P. Generic Dimensions of Teaching Quality: The German Framework of Three Basic Dimensions. ZDM—Math. Educ. 2018, 50, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.A.; Greenberg, M.T. The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom Outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubbels, T. An International Perspective on Classroom Management: What Should Prospective Teachers Learn? Teach. Educ. 2011, 22, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, A.W.; Weinstein, C.S. Student and Teacher Perspectives on Classroom Management. In Handbook of Classroom Management; Evertson, C.M., Weinstein, C.S., Eds.; Routledge/Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 191–230. [Google Scholar]

- Scherzinger, M.; Wettstein, A. Classroom Disruptions, the Teacher–Student Relationship and Classroom Management from the Perspective of Teachers, Students and External Observers: A Multimethod Approach. Learn. Environ. Res. 2019, 22, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, M. Secondary School Teachers’ Perceptions of Student Misbehaviour: A Review of International Research, 1983 to 2013. Aust. J. Educ. 2015, 59, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, E. Secondary School Teachers’ Perceptions of Students’ Problem Behaviours. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, A.; Ramseier, E.; Scherzinger, M.; Gasser, L. Unterrichtsstörungen Aus Lehrer-Und Schülersicht [Classroom Disorders from the Teacher and Student Perspective]. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, F.; Wilks, R. A Survey of 45 Primary School Teachers Self-Perceived Discipline Styles: A Pilot Study; Wilks, R., Ed.; RMIT University Department of Psychology and Disability: Bundoora, VIC, Australia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Emmer, E.T.; Evertson, C.M.; Worsham, M.E. Classroom Management for Middle and High School Teachers; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Evertson, C.M.; Emmer, E.T. Classroom Management for Elementary Teachers, 10th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alpert, B. Students’ Resistance in the Classroom. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 1991, 22, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumschick, I.R.; Piwowar, V.; Thiel, F. Inducing Adaptive Emotion Regulation by Providing the Students’ Perspective: An Experimental Video Study with Advanced Preservice Teachers. Learn. Instr. 2018, 53, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumschick, I.R.; Torchetti, L.; Gasser, L.; Tettenborn, A. How Controllable versus Uncontrollable Cognitions Affect Emotion Processing during Classroom Disruptions: A Video Study with Preservice Teachers. Teach. Teach. 542 Educ. 2023, 135, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.A. Student Resistance: How the Formal and Informal Organization of Classrooms Facilitate Everyday Forms of Student Defiance. Am. J. Sociol. 2001, 107, 612–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, F. Interaktion Im Unterricht: Ordnungsmechanismen Und Störungsdynamiken [Interaction in the Classroom: Mechanisms of Order and Dynamics of Disruption]; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, T.J.; Sugai, G. Effective Behavior Support: Systems Approach to Proactive Schoolwide Management. Focus Except. Child. 1999, 31, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kumschick, I.R.; Piwowar, V.; Ophardt, D.; Barth, V.; Krysmanski, K.; Thiel, F. Optimierung Einer Videobasierten Lerngelegenheit Im Problem Based Learning Format Durch Cognitive Tools. Eine Interventionsstudie Mit Lehramtsstudierenden [Optimization of a Video-Centered Learning Arrangement in a Problem-Based Learning Format Through Cognitive Tools: An Intervention Study with Pre-Service Teachers]. Z. Für Erzieh. 2017, 20, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömeke, S.; Gustafsson, J.-E.; Shavelson, R.J. Approaches to Competence Measurement in Higher Education; Hogrefe Publishing: Göttingen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kumschick, I.R. Dealing with Feeling. Emotionsregulation Als Ausbildungsbaustein [Emotion Regulation as a Component of Teacher Education]. J. Für LehrerInnenbildung Jlb 2022, 22, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumschick, I.R. Ärger—Die Unerwünschte Emotion Im Klassenzimmer [Anger—The Unwanted Emotion in the Classroom]. Erzieh. Unterr. 2023, 173, 134–144. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, C.; Lam, S. The Effects of Regulatory Focus on Teachers’ Classroom Management Strategies and Emotional Consequences. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 28, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kolbe, M.; Seelandt, J.; Nef, A.; Grande, B. Simulation Und Forschung [Simulation and Research]. In Simulation in der Medizin [Simulation in Medicine]; St.Pierre, M., Breuer, G., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Korpershoek, H.; Harms, T.; De Boer, H.; Van Kuijk, M.; Doolaard, S. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Classroom Management Strategies and Classroom Management Programs on Students’ Academic, Behavioral, Emotional, and Motivational Outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 643–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienefeld, N.; Grote, G. Shared Leadership in Multiteam Systems: How Cockpit and Cabin Crews Lead Each Other to Safety. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2014, 56, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahvar, T.; Farahani, M.A.; Aryankhesal, A. Conflict Management Strategies in Coping with Students’ Disruptive Behaviors in the Classroom: Systematized Review. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 2018, 6, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual Differences in Two Emotion Regulation Processes: Implications for Affect, Relationships, and Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.R. Development and Validation of an Internationally Reliable Short-Form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Schielzeth, H. A General and Simple Method for Obtaining R 2 from Generalized Linear Mixed-effects Models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, J. Informationstheoretische Masse [Information-Theoretical Measures]. In Lexikon der Psychologie [Encyclopedia of Psychology]; Wirtz, M.A., Ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Ishiguro, M.; Kitagawa, G. Akaike Information Criterion Statistics; Reidel Publ. Co.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- SKBF—Schweizerische Koordinationsstelle für Bildungsforschung. Bildungsbericht Schweiz 2014; SKBF: Aarau, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J.; Layard, R. A Good Childhood: Searching for Values in a Competitive Age; Penguin: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, S.; Wheldall, K.; Merrett, F. Classroom Behaviour Problems Which Secondary School Teachers Say They Find Most Troublesome. Br. Educ. Res. J. 1988, 14, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, T.J.; Kauffman, J.M. Behavioral Approaches to Classroom Management. In Handbook of Classroom Management; Everton, C.M., Weinstein, C.S., Eds.; Routledge/Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, C.E.; Jarodzka, H.; Boshuizen, H.P.A. Classroom Management Scripts: A Theoretical Model Contrasting Expert and Novice Teachers’ Knowledge and Awareness of Classroom Events. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, S.; Kleen, H. The Role of Preservice Teachers’ Implicit Attitudes and Causal Attributions: A Deeper Look into Students’ Ethnicity. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 8125–8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C. Can Instructional and Emotional Support in the First-Grade Classroom Make a Difference for Children at Risk of School Failure? Child Dev. 2005, 76, 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granero-Gallegos, A.; Gómez-López, M.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Martínez-Molina, M. Interaction Effects of Disruptive Behaviour and Motivation Profiles with Teacher Competence and School Satisfaction in Secondary School Physical Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, C.M.; Ponitz, C.C.; Phillips, B.M.; Travis, Q.M.; Glasney, S.; Morrison, F.J. First Graders’ Literacy and Self-Regulation Gains: The Effect of Individualizing Student Instruction. J. Sch. Psychol. 2010, 48, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mischel, W. Der Marshmallow-Test: Willensstärke, Belohnungsaufschub und die Entwicklung der Persönlichkeit [The Marshmallow Test: Willpower, Delay of Gratification, and Personal Development]; Siedler Verlag: München, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux, J. The Emotional Brain, Fear, and the Amygdala. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2003, 23, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDoux, J.E. The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chernikova, O.; Heitzmann, N.; Stadler, M.; Holzberger, D.; Seidel, T.; Fischer, F. Simulation-Based Learning in Higher Education: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2020, 90, 499–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

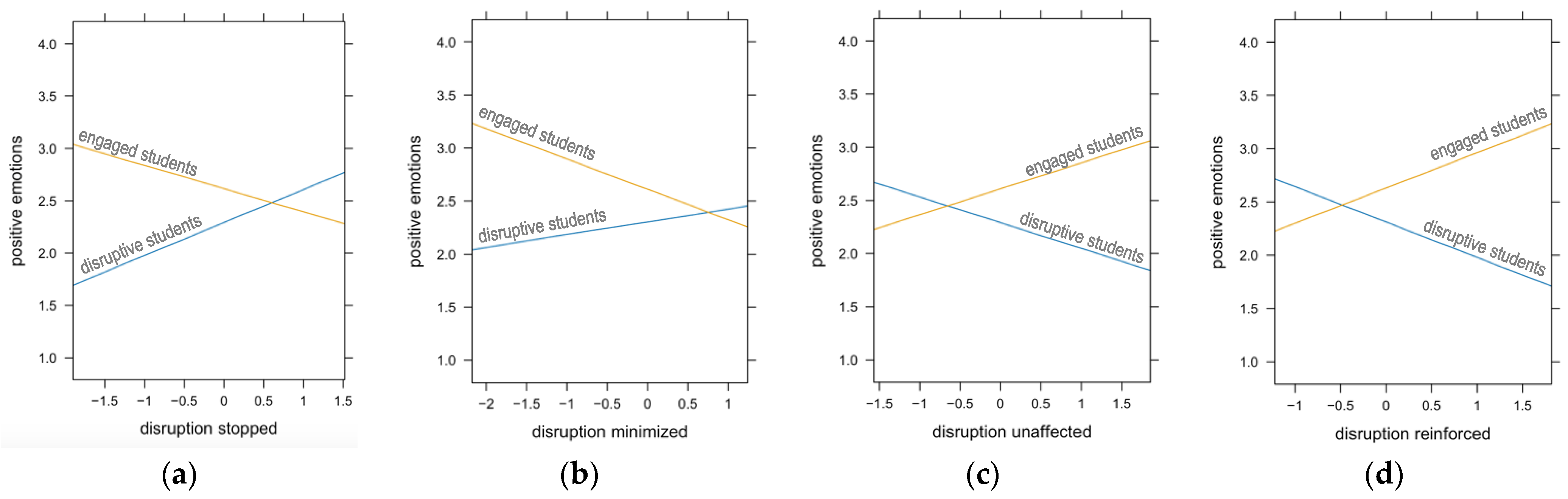

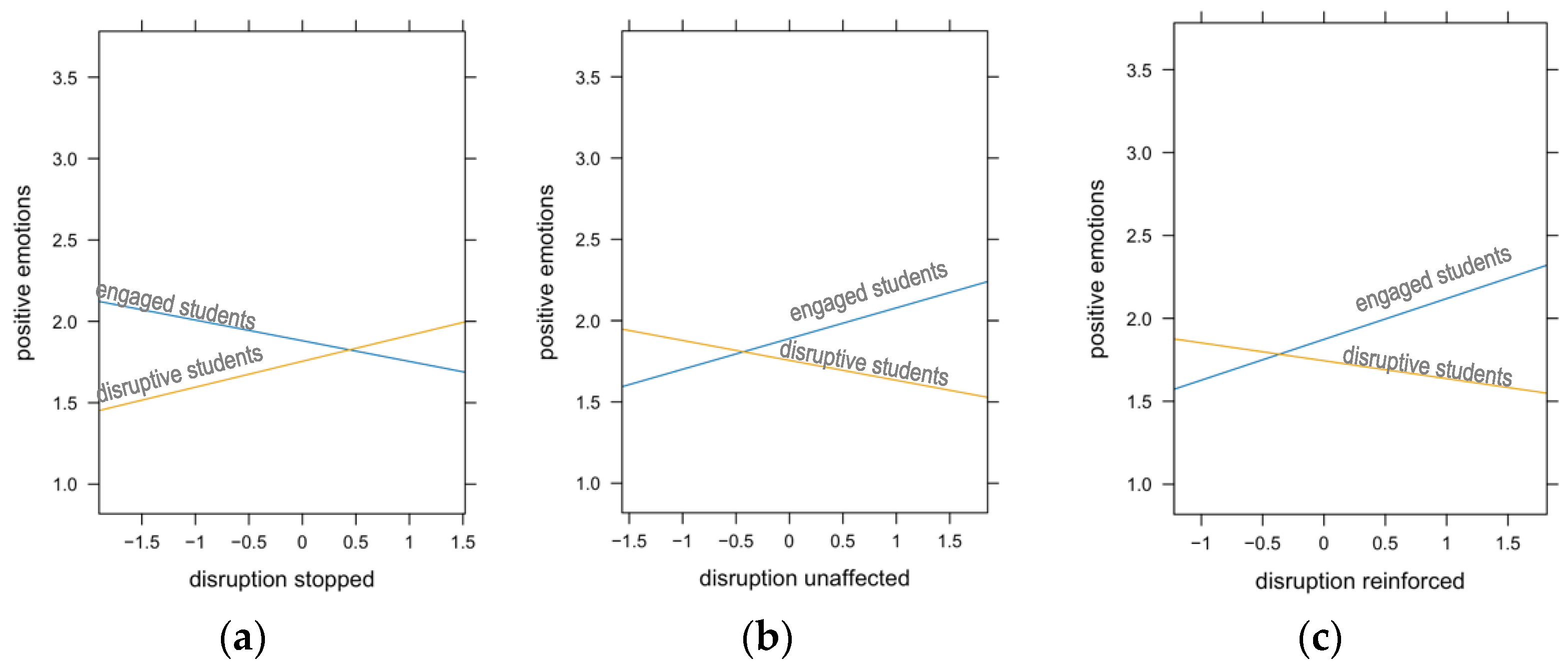

| Teacher Did … | Engaged Students Perceive More … | Disturbing Students Perceive More … | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Emotions | Negative Emotions | Positive Emotions | Negative Emotions | |

| … stop the disturbance | «+» | «−» | «−» | «+» |

| … minimize the disturbance | «+» | «−» | «-» | «+» |

| … not influence the disturbance | «−» | «+» | «+» | «−» |

| … increase the disturbance | «−» | «+» | «+» | «−» |

| Topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Name | Affective-behavioural-cognitive training (abc training) to foster disruption management in preservice teachers. |

| Target Recipient | Advanced preservice teachers enrolled in a master’s degree course for secondary school teachers at the University of Teacher Education Lucerne (CH) |

| Duration | 6-weeks program. |

| Characteristic | Compressed intervention with theoretical input in the first two lessons on the topic of disruption management strategies, emotions, and emotion regulation. |

| Agreement | Preservice teachers sign a confidentiality agreement in advance to create a protected climate, pledging not to disclose the contents of the seminar to external parties in order to protect all individuals participating in the training. |

| Theoretical Background | Five-Components-Model of Emotion [14,15] and Model of Five Strategies of Emotion Regulation [58]. |

| Teaching Method | Simulations: Classroom disruptions are simulated after the theoretical input. Preservice teachers take on different roles: teacher or engaged/disturbing student. Immediately after the simulation, all preservice teachers are requested to fill out a questionnaire * in their respective roles, indicating personal perceptions regarding emotions, cognitions, behaviour, and how the disruption management worked. |

| Variables | M (SD) | Ω b | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Affect | 2.47 (0.70) | 0.82 | ||||||

| 2. Negative Affect | 1.80 (0.63) | 0.70 | −0.53 *** | |||||

| 3. Student role a | 0.49 | 0.23 ** | −0.13 | |||||

| 4. Disruption stopped | 2.69 (0.67) | 0.78 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.05 | |||

| 5. Disruption minimised | 3.06 (0.61) | 0.65 | −0.08 | 0.10 | −0.10 | 0.65 *** | ||

| 6. Disruption unaffected | 2.36 (0.63) | 0.60 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.11 | −0.63 *** | −0.54 *** | |

| 7. Disruption reinforced | 2.04 (0.54) | 0.66 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.41 *** | −0.37 *** | 0.47 *** |

| Null Model | Disruption Stopped | Disruption Minimised | Disruption Unaffected | Disruption Increased | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | |

| Intercept | 2.37 (0.05) *** | 2.45 (0.05) *** | 2.45 (0.05) *** | 2.32 (0.06) *** | 2.47 (0.05) *** | ||||

| Role a | 0.32 (0.10) ** | 0.23 ** | 0.31 (0.10) ** | 0.22 ** | 0.32 (0.10) ** | 0.23 ** | 0.32 (0.10) ** | 0.23 ** | |

| Disruption manag. | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.05 | −0.03 (0.08) | −0.02 | −0.00 (0.08) | −0.00 | −0.00 (0.09) | −0.00 | |

| Interaction term b | −0.55 (0.16) *** | −0.26 *** | −0.51 (0.17) ** | −0.22 ** | 0.49 (0.17) ** | 0.22 ** | 0.66 (0.19) *** | 0.25 *** | |

| ICC | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| R2-Marginal | 0.000 | 0.116 | 0.104 | 0.100 | 0.118 | ||||

| AIC | 360.2 | 345.6 | 347.9 | 348.6 | 345.2 | ||||

| Null Model | Disruption Stopped | Disruption Minimised | Disruption Unaffected | Disruption Increased | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | |

| Intercept | 1.88 (0.05) *** | 1.82 (0.05) *** | 1.82 (0.05) *** | 1.82 (0.05) *** | 1.81 (0.05) *** | ||||

| Role a | −0.14 (0.09) | −0.11 | −0.12 (0.10) | −0.10 | −0.14 (0.10) | −0.11 | −0.13 (0.09) | −0.11 | |

| Disruption manag. | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.04 | 0.10 (0.08) | 0.10 | 0.03 (0.08) | 0.03 | 0.07 (0.09) | 0.06 | |

| Interaction term b | 0.29 (0.15) * | 0.15 * | 0.14 (0.16) | 0.07 | −0.31 (0.16) * | −0.15 * | −0.35 (0.18) * | −0.15 * | |

| ICC | 0.012 | 0.035 | 0.029 | 0.014 | 0.011 | ||||

| R2-Marginal | 0.000 | 0.041 | 0.028 | 0.034 | 0.037 | ||||

| AIC | 323.8 | 323.1 | 325.2 | 324.0 | 323.6 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumschick, I.R.; Tschopp, C.; Troesch, L.M.; Tettenborn, A. Disruption Management Interacts with Positive and Negative Emotions in the Classroom: Results from a Simulation-Based Study. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090966

Kumschick IR, Tschopp C, Troesch LM, Tettenborn A. Disruption Management Interacts with Positive and Negative Emotions in the Classroom: Results from a Simulation-Based Study. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(9):966. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090966

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumschick, Irina Rosa, Cécile Tschopp, Larissa Maria Troesch, and Annette Tettenborn. 2024. "Disruption Management Interacts with Positive and Negative Emotions in the Classroom: Results from a Simulation-Based Study" Education Sciences 14, no. 9: 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090966

APA StyleKumschick, I. R., Tschopp, C., Troesch, L. M., & Tettenborn, A. (2024). Disruption Management Interacts with Positive and Negative Emotions in the Classroom: Results from a Simulation-Based Study. Education Sciences, 14(9), 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090966